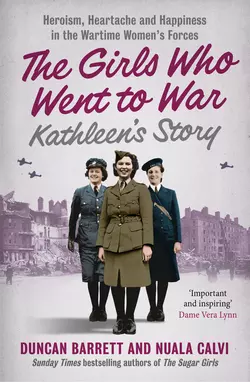

Kathleen’s Story: Heroism, heartache and happiness in the wartime women’s forces

Duncan Barrett

Calvi Calvi

From the bestselling authors of The Sugar Girls and GI Brides, this is Kathleen’s story, one of three true accounts from the book The Girls Who Went to War.“Boxing Day was cold and frosty, and by the time Kathleen and the lads arrived at the football pitch she was already shivering. As they stood watching the game, Arnold silently took her hand and put it inside the pocket of his greatcoat. It was a small gesture, but it told her that she belonged to him now, and to Kathleen nothing had ever seemed so romantic.”In the summer of 1940, Britain stood alone against Germany. The British Army stood at just over one and a half million men, while the Germans had three times that many, and a population almost twice the size of ours from which to draw new waves of soldiers. Clearly, in the fight against Hitler, manpower alone wasn’t going to be enough.Nanny Kathleen Skin signed up for the WRNS, leaving her quiet home for the rigours of training, the camaraderie of the young women who worked together so closely and to face a war that would change her life forever.Overall, more than half a million women served in the armed forces during the Second World War. This book tells the story of just one of them. But in her story is reflected the lives of hundreds of thousands of others like them – ordinary girls who went to war, wearing their uniforms with pride.

(#ua35f24a4-f596-5fbf-9936-81576f15535f)

Copyright (#ua35f24a4-f596-5fbf-9936-81576f15535f)

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2015

© Duncan Barrett and Nuala Calvi 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs (not representations of the women portrayed herein) © George W. Hales/Getty Images (WAAF officer); The Everett Collection/Mary Evans Picture Library (military officer); IWM Collection (WRNS officer); London Fire Brigade/Mary Evans Picture Library (background)

Duncan Barrett and Nuala Calvi assert the moral right

to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780007501229

Ebook Edition © May 2015 ISBN: 9780007517565

Version: 2015-03-17

Contents

Cover (#u47209930-8d28-5dbc-bb0a-bbb9caff5390)

Title Page (#ulink_e7156ad8-13e6-5427-b044-2c0b10bf34c2)

Copyright (#ulink_d29c7cb8-5a69-5f9d-93c4-91cf7311f32e)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_9c3e1c48-4604-52d9-af84-981e98592591)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_393de295-1cbb-5634-a38d-4597f95a26e4)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_59adc7f6-25a2-5630-be2f-df5566540868)

Chapter 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Authors (#litres_trial_promo)

Exclusive sample chapter (#litres_trial_promo)

If you like this, you’ll love … (#litres_trial_promo)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#litres_trial_promo)

Write for Us (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 1 (#ua35f24a4-f596-5fbf-9936-81576f15535f)

Although thousands of girls up and down the country were joining up for the fight against Germany, not many of them could claim to have actually seen Hitler in person. But Kathleen Skin, a 19-year-old nanny from Cambridgeshire, was something of a rarity. In August 1939, she was staying at a hotel in Cologne when it was visited by some very high-profile guests.

Kathleen was on her way to a church summer camp in Denmark, and was staying in one of the hotel’s cheapest rooms, up by the servants’ quarters in the attic. One evening as she was returning to her room, a housemaid came up to her and whispered, ‘Do you want to see the Führer?’

‘What, here?’ Kathleen replied, astonished.

‘Yes,’ the girl said, excitedly. ‘He comes tonight for dinner. You can look from up here, but do not let anyone see you.’

‘All right,’ Kathleen said, taking up a good viewing position at the top of the stairs. She was eager to catch a glimpse of the man whose name was on the lips of everyone in Europe.

Peering down the stairwell, Kathleen watched as a little man in uniform strode into the hotel, accompanied by a large entourage. A quick glimpse of his famous toothbrush moustache was enough to convince her that it really was Hitler. It was strange to think that such a small, unimpressive-looking person could be holding the whole world to ransom.

After a couple of moments, the official party was whisked into the dining room. Kathleen crept back to her bedroom, pleased that she would be able to go home and tell her family that she’d actually seen the German chancellor.

Since childhood, Kathleen had always been gripped by a lust for travel. She had learned to read at an early age, and had devoured Robinson Crusoe and Swiss Family Robinson, dreaming of one day visiting such exotic lands herself. She loved nothing more than listening to her father tell stories about his adventures in India when he was a young man in the Army, or her mother’s tales of growing up in South Africa, where her Danish grandparents had moved during the gold rush.

Kathleen’s parents had met when William Skin was on his way back to Britain to be demobbed. While he was passing through Cape Town, a naval revolt had broken out, and he and his fellow soldiers had found themselves ordered to disembark and take over, until replacement sailors were sent out by the Navy. While he was there he had joined the local glee club and been enchanted by the red hair and green eyes of the lovely Amelia. He had promised to return and marry her as soon as he left the Army, but their romantic plans were scuppered by the outbreak of the First World War. Mr Skin was one of the first to be sent over to France, where his trench was so badly shelled that the stretcher-bearers left him for dead. It was only when a burial party came around to collect the dead bodies that they realised he was still alive and rushed him to hospital.

In time, Mr Skin had recovered sufficiently to be able to walk again, but the muscles and tendons in one leg were so badly damaged that he was left with a strange lolloping gait. He had lost the sight in one eye and his hearing had been affected too. He was convinced his beloved would no longer want him in his current state, but Amelia insisted he return to Cape Town and marry her, despite her parents’ protestations that she was shackling herself to an invalid.

Mr Skin brought his new wife back with him to England and their family soon began to grow, but with just his pension from the Army to live on, feeding their five children grew increasingly hard. Throughout Kathleen’s childhood, the family moved from village to village around Cambridgeshire, always going where the housing was cheapest. Wherever they went, they were seen as eccentrics. Mrs Skin scandalised the local women by allowing her daughters to wear trousers, while her husband was the only man they knew who was happy to push a pram for his wife.

Kathleen had inherited her mother’s striking red hair and green eyes, as well as her gift for performance. She and her sisters would compose poetry and plays that they put on for the village children, and her older sister Lila kept her friends in the playground enthralled with tales of how she was really a princess, forced to live in poverty until she could one day return to reclaim her palace.

The Skins’ house was always a favourite with the local kids, thanks to the unusual and imaginative games the family played. But one day when the other children had all left, Mr Skin turned to Kathleen and asked, ‘Why don’t you go home as well?’

‘I am home, Dad,’ Kathleen replied, wondering if her father was playing some kind of joke.

‘No, you’re not,’ her father insisted. ‘You’re not one of mine.’

Kathleen did her best to shrug off the strange remark, but it wasn’t long before her father was exhibiting other odd behaviours. Mr Skin had imparted a love of nature to his children, dragging them out of bed in their pyjamas to witness flocks of migrating birds coming over from Africa, or to count falling stars. But now he began talking to the birds as if they could understand him, and disappearing for hours on end, no one knew where. When he was found one day wandering the roads with no idea who he was, the whole family was forced to acknowledge that something was seriously wrong, and Mr Skin allowed himself to be taken to Fulbourn mental hospital.

X-rays eventually revealed that the shell that had almost killed Mr Skin in the war had left bits of shrapnel scattered throughout his brain. The peculiar effects came and went – for months at a time he would be perfectly fine and was able to return home to his family, but then the madness would begin again, and he would have to go back to the asylum.

Kathleen was a bright girl, but her educational prospects had been limited. Her older sisters Maevis and Lila had gone to grammar school, but by the time her turn came around there simply wasn’t the money to send her – even though she had won a part-scholarship from the council. Instead, she attended the local technical school, where even her teachers admitted that her academic abilities were wasted. Kathleen found many of the classes there dull, but she did enjoy the weekly childcare lessons. She loved bathing the tiny babies and learning about their development, so when she left school she decided to become a nanny.

Kathleen had been working for a doctor’s family in West London when the opportunity came up to visit Denmark with the church summer camp. Her employers had willingly given her the time off, and she spent an enjoyable few days swimming in the sea and learning to sail a dinghy.

On her way back through Germany, she stayed with a family in Kiel who her father had befriended after the war, in the belief that if old enemies could bury the hatchet it might help prevent another major conflict. They had three strapping blond blue-eyed boys, the oldest of whom, Konrad, was about her age.

One day, the boys invited Kathleen to come with them on an organised march through the local countryside. ‘It will be great fun,’ Konrad told her enthusiastically. Never one to turn down a chance for adventure, Kathleen agreed, joining the three lads as they set off in matching brown shirts with swastika armbands.

They met up with a group of younger boys and girls who Konrad explained were Deutsches Jungvolk – the junior section of the Hitler Youth. As the march progressed, they were joined by more and more young people, until Kathleen found herself among hundreds of German youngsters all dressed in Nazi uniforms.

The march culminated in a huge rally where everyone performed the Hitler salute together. For a British girl, far from home, it was a strange and unsettling spectacle to witness.

When the boys brought Kathleen back to their house that evening, their father was waiting for her anxiously. ‘You must pack your bags now,’ he told her. ‘It is time for you to leave.’

‘But I’ve still got a few days’ holiday left,’ she protested.

‘No, you must go now,’ the man insisted. ‘You cannot be in Germany.’

He found a friend with a car and took the bewildered girl to the Dutch border, where he gave her instructions to catch a ferry back to England.

Two days later, German forces invaded Poland. Kathleen had scarcely got back to British soil before her country found itself at war with Germany.

The family Kathleen was working for had fled London for Wales, anxious to get their baby daughter out of harm’s way. She joined them again in the small seaside town of Tenby, where they were staying with the doctor’s elderly mother. In addition to her other duties, Kathleen now found she had to wait on the demanding old lady as well.

Kathleen wished that her job could take her to somewhere more exotic than Wales, but she had always loved the ocean, and enjoyed the sea view from her new room. She soon made friends in Tenby among the nannies of other well-to-do families who had evacuated themselves from London. She looked forward to the afternoons, when they would go for long walks together, pushing their prams along the sea front.

The girls often went up to Saundersfoot, a pretty village with a harbour a little way up the coast. One day they arrived to find that it was crawling with soldiers. ‘What on earth’s going on?’ one of the other nannies wondered.

‘Why don’t we find out?’ said Kathleen, going straight up to the nearest man in uniform. ‘What are you lot doing here?’ she asked boldly.

‘We’re here to practise our shooting,’ the man told her proudly. ‘We’re training with the Royal Artillery.’

As he finished speaking, Kathleen heard the sound of guns in the distance. A round was being fired out to sea.

‘Ooh, listen to that!’ remarked Kathleen’s friend excitedly. But as they pushed their prams along the seafront that afternoon, the girls found the sight of the handsome soldiers far more distracting than the noise of the guns. There were plenty of young officers about, and as they passed the young ladies they smiled and touched their hats, aware of the effect their uniforms were having.

When Christmas came, Kathleen used her time off to go home and keep her mother company. Poor Mr Skin would be spending the festive season in the asylum, and by now all but one of the children – Kathleen’s youngest brother Lance – had joined the forces. Her eldest sister Maevis was in the ATS, her brother Cecil had joined the RAF and her sister Lila was in the WRNS, working on a naval base at Scapa Flow. Mrs Skin, meanwhile, had taken a job as a nurse at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, which allowed her to pay the rent on a little house on Pembroke Street, not far from Lance’s school.

‘Hello, Mum,’ Kathleen said as she arrived home for the holiday, giving her mother a big hug. ‘What do you want to do while I’m here?’

‘I’d love to go and hear the carols at King’s,’ Mrs Skin told her. She had always loved classical music but the family finances rarely stretched to the kind of concerts she had enjoyed while growing up in Cape Town.

On Christmas Eve, Kathleen and her mother joined the queue outside King’s College Chapel, hoping to get a place for the three o’clock service. They were among the last to be admitted, but managed to find a pew near the back.

As the organist began playing the introduction to ‘It Came Upon a Midnight Clear’, three soldiers squeezed up next to them. They only had one hymn sheet between them, and the man next to Kathleen was humming along, obviously unable to see the words. She tapped his arm and offered to share her hymn sheet, and he began singing more confidently. He had a beautiful voice which rang out above those of everyone around him.

Throughout the service she was aware of the man looking at her now and then, and when it came to an end, he turned to speak to her. ‘I didn’t know you lived in Cambridge,’ he said. ‘I’ve seen you down in Saundersfoot, haven’t I?’

The man was tall and blond, a good six or seven years older than Kathleen. Now that she looked at him properly, she recognised him as one of the handsome young officers whose presence had brightened up her daily walks with the other nannies. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I work in Tenby as a nanny. My name’s Kathleen.’

‘Lieutenant Arnold Karlen, at your service,’ the man said, offering her his hand.

‘Kathleen, who is this young man?’ asked Mrs Skin, craning round to see what was going on. Kathleen introduced Arnold to her mother, and saw her look approvingly at his officer’s uniform. ‘Well, Merry Christmas lads,’ she said to the three soldiers. ‘Won’t you let us give you a cup of tea? We’re only a minute away from here.’

Kathleen was a little surprised at her mother inviting three strangers into their house, but with her only adult son away with the Air Force, Mrs Skin was keen to extend her hospitality to some other young men away from home at Christmas.

Soon the three soldiers had piled into the little house on Pembroke Street, and Mrs Skin was boiling the kettle. Kathleen went into the kitchen to help and saw that she was spreading a very generous amount of butter onto the young men’s slices of bread.

‘Mum, are you sure you can afford to give them that much of your week’s ration?’ she asked anxiously.

‘Oh, don’t worry,’ her mother replied, hastily piling up the bread and adding some slices of Christmas cake to the tray as well.

The soldiers took the food gratefully, complimenting Mrs Skin on the cake. ‘So where are you boys staying?’ she asked them.

‘We’ve pitched our tents on a playing field at The Leys School,’ replied Arnold. Kathleen sensed that he was the leader of the little group. His friends, John and ‘Ding-Dong’ – Kathleen later learned that his surname was Bell – always seemed to wait for him to speak first, treating him with an air of respect.

‘A tent’s no place to be spending Christmas!’ Mrs Skin exclaimed. ‘Will you at least get a proper Christmas dinner?’

‘Oh, there’ll be a good dinner – especially for the men,’ Arnold replied with a laugh. ‘On Christmas Day us officers have to serve them, and I’m sure they’ll make the most of it!’

‘It must be so difficult being in charge of all those people,’ Kathleen remarked thoughtfully.

‘It certainly can be!’ Arnold replied. Before long, he had Mrs Skin, Kathleen and her awed little brother Lance laughing at his tales of life as a newly commissioned officer, and the trials and tribulations of trying to keep the rank and file in order. He was a natural storyteller, and as he spoke he seemed to hold the room in the palm of his hand. Kathleen, who was quite a performer herself, felt she had never met anyone quite so charming. She was utterly entranced, and she could see that her mother was too.

Before they knew it, an hour had passed and the men were due back at their campsite. ‘Well, thank you, Mrs Skin – this has been delightful,’ Arnold said, taking her hand. Then he turned and flashed a look at Kathleen, adding, ‘I hope we see each other again.’ Her heart leapt at his words.

‘Our door’s always open!’ Mrs Skin called after the three soldiers. When they had gone, she turned to Kathleen and exclaimed, ‘Well, what a lovely young man! I think he took quite a shine to you.’

Kathleen smiled. For the rest of the evening she could think of nothing but the handsome blond officer, and the following day, as she helped her mother prepare the Christmas lunch, her mind kept wandering back to all the little things he had said, how clever and funny he had been, and how unlike other men she had met. She had been on the odd date with boys her own age, but in comparison to Arnold they seemed like awkward, clumsy kids. He was a man of the world, the kind of man who could show you adventure and excitement, and she longed to see him again.

As it turned out, Kathleen’s wish was granted sooner than she could have hoped. On the afternoon of Christmas Day she was sitting by the fire with her mother and her brother Lance, when suddenly the front door opened a few centimetres and three soldiers’ caps came flying into the room, landing on the floor by their feet. Kathleen and her mother looked at each other in surprise.

‘It means, “May we come in?”’ a familiar voice called from behind the door.

‘Oh yes, of course!’ Mrs Skin cried, jumping up from her chair to welcome the three young soldiers back into the house.

‘We come bearing gifts!’ said Arnold, offering up an enormous parcel of food which he explained was left over from their Christmas dinner.

‘Oh, you shouldn’t have!’ said Mrs Skin, but after the meagre meal she had managed to scrape together that day the gift was more than welcome.

Soon everyone was tucking into the unexpected treats, while Arnold again regaled them with jokes and stories. His friend John had been in an orchestra before the war and had brought along his oboe and a tin whistle, and in between Arnold’s amusing tales he kept the little group entertained with music. The Skin family’s rather quiet Christmas had suddenly turned into quite the party. But for Kathleen, it was the moments when Arnold threw her a lingering look that felt most special.

Before the soldiers left, they mentioned a football match that was being held at the boys’ school the following afternoon, and Arnold asked if Kathleen would like to attend.

‘Oh, I’m sure she’d love to, wouldn’t you?’ Mrs Skin piped up, before her daughter even had a chance to reply.

Boxing Day was cold and frosty, and by the time Kathleen and the lads arrived at the football pitch she was already shivering. As they stood watching the game, Arnold silently took her hand and put it inside the pocket of his greatcoat. It was a small gesture, but it told her that she belonged to him now, and to Kathleen nothing had ever seemed so romantic.

When Kathleen returned to Tenby she was delighted to find that Arnold’s battery had been sent back to Saundersfoot for further training, and they began meeting on his nights off from the firing camp. They took walks together along the sea front or sat kissing on one of the little benches looking out to sea. They told each other all about their families and their childhoods, and Kathleen learned that Arnold’s father had come over from Switzerland to take a job as a top chef at a five-star restaurant in London. He had fallen in love with an English rose and had three boys by her, all of whom were now in the forces.

Arnold was just as charming and romantic as he had been in Cambridge, and when Kathleen was alone with him he made her feel like the centre of the universe. ‘You know, I think we’re meant for each other,’ he told her one evening, gazing at her with his piercing blue eyes.

Kathleen felt the same. She barely knew Arnold, yet she had no doubt in her mind that this was true love. Her every waking moment was filled with thoughts of him.

But Arnold’s battery was only in Saundersfoot for a short time, and soon they were posted to Scotland. ‘I’ll write to you all the time, my darling,’ he promised Kathleen. ‘Don’t forget me.’

Soon letters began arriving that were even more romantic than Arnold had been in person. He wrote that his heart yearned for Kathleen, that he longed to see her beautiful face again and stroke her lovely red hair. Kathleen treasured every missive, as if they were the most precious objects in the world.

Since she had first come to Tenby, Kathleen had felt as though the war was far away, but now she began to see signs of the horrors happening in the rest of the world. Strange things began washing up on the beach next to the house – sailors’ hats, foreign money and parts from naval and merchant vessels that had been sunk by German U-boats. One day she discovered a whole crate of oranges, which she and the other nannies shared among their children. Another time half a dozen boxes of toothbrushes appeared, and she took them down to the port authority in the town. She knew items of interest had to be reported, particularly if they had numbers on them that could be traced back to specific ships.

But one afternoon, a haul washed up that no one wanted to go near. Kathleen and the baby had just had lunch when she looked out of the window to see a strange tangled mess sprawled along the beach. She went outside and began to walk down the stone steps to get a closer look, but as she got nearer she realised with a start that there were around 20 human bodies strewn across the sand, all in a state of partial decomposition.

Struggling to keep down her lunch, Kathleen ran back upstairs, put the baby in her pram and rushed to the port authority to report the gruesome discovery. That afternoon the corpses were wrapped up and discreetly taken away, but Kathleen was left sickened by what she had seen.

A few weeks later, Kathleen witnessed another sight that she was unable to forget. Thanks to its large docks and nearby oil refinery, Swansea was a prime target for the Luftwaffe, and on 19 February 1941 it was hit by a ferocious bombing campaign. Over three days, 800 high explosives and more than 35,000 incendiaries fell on the city, causing raging fires, destroying its ancient centre and killing and injuring hundreds of people.

The blaze could be seen for miles around, and as Kathleen stood watching it from Tenby she felt her heart fill with fury. She knew then and there that her days as a nanny were over. She had to get out and join the fight.

She had seen a newspaper advertisement calling on women to join up with one of the three armed forces. With her love of the sea, Kathleen was particularly attracted to the idea of the WRNS, and she hoped that joining the Navy might offer the chance to visit some of the exotic places she had read about as a child. It didn’t hurt that, of all the women’s forces, the WRNS had by far the most stylish uniform.

Kathleen wrote to the address given in the paper, and soon received some forms to fill in. A week later she was invited to attend an interview at her local recruiting office. There she was grilled by a man and woman dressed in the smart blue uniforms of naval officers. They asked her about her health, qualifications and any relevant experience she might have – as well as some rather surprising queries about boyfriends and personal hygiene.

Kathleen answered the string of questions as best she could, doing her best to impress upon her interviewers how desperate she was to do her bit for her country. There was no getting around the fact that the skills she had picked up nannying weren’t exactly transferable to anything she might be expected to do as a Wren, but her obvious enthusiasm must have won them over. ‘All right, we’ll try you out,’ the woman announced at last. Kathleen couldn’t have been more thrilled.

‘You’ll have to pass a medical exam,’ the Wren officer continued, ‘but I’m sure you’ll have no trouble there. If you’re used to running around after young children you must be reasonably fit.’

The medical was to take place at a local doctor’s surgery in Tenby, and Kathleen asked her employer if she could have a few hours’ off to attend. She knew that competition for the WRNS was tough, and the medical standards for entry were high – generally only those passed as Grade I were accepted.

Kathleen was in good shape and she performed well in the physical tests, bending down, spinning around and walking along a chalk line to prove that she did not easily get giddy, and assuring the doctor that she wasn’t prone to seasickness. By the end of the examination, she felt confident that she had passed, and eagerly awaited her results.

At last the doctor came out to see her. ‘Grade I,’ he told her approvingly, looking up from a clipboard he was holding.

Kathleen jumped up from her seat, smiling, but the man put his hand out to stop her. ‘I’m afraid I can’t pass you, though,’ he said.

‘Why not?’ she demanded.

‘You’re too thin,’ the doctor replied. ‘The minimum for the WRNS is six stone, and you’re a few pounds under. I’m sorry.’

He turned and walked away with his clipboard under his arm, leaving Kathleen utterly gobsmacked. She had passed all the fitness tests, she had proved her worth. Yet for the sake of a few pounds her dream of serving in the Navy had been thwarted.

Dejectedly, Kathleen returned home and began preparing the baby’s dinner, staring longingly out of the window at the sea.

Chapter 2 (#ua35f24a4-f596-5fbf-9936-81576f15535f)

Being rejected by the WRNS had been a bitter disappointment for Kathleen, but she wasn’t going to let it stop her doing her bit for the war effort. If the Navy wouldn’t take her now, she reasoned, she would just have to find something else to do until it was ready for her.

She had seen posters in town calling on women to join the Land Army – ‘for a healthy, happy job’ as they put it. The pictures showed girls standing in golden fields of corn, tilling the soil, gathering hay and tending to cute farm animals. The life of a land girl looked distinctly appealing, and even if the work was hard, the camaraderie would surely make up for that.

Kathleen handed in her notice with the family she was nannying for in Wales, telling them she was going back home to Cambridge. She was sorry to say goodbye to the little girl she had been looking after, but she felt it was for the best. The child was beginning to grow so attached to her that many people seeing them out together assumed she was her mother.

Once she got home, Kathleen lost no time in presenting herself at a recruiting centre, where she was interviewed by a rather superior woman who wanted to know if she had a farming background.

‘Well, I used to help my father grow vegetables in the garden,’ she replied, hopefully.

‘Horticulture for you then,’ the woman declared. ‘You’ll get your call-up soon, so be ready.’

A week later, Kathleen was on the train to Bury St Edmunds, ready to take up her first posting. She arrived at the station to find a rather luxurious-looking car waiting for her, along with a chauffeur who introduced himself as Bradley. ‘I’ve been sent to collect you,’ he explained.

Kathleen got in, wondering what kind of farm had its own chauffeur. They headed out into the countryside for a while, before turning up the gravel drive of a grand mansion, whose once carefully manicured gardens had been given over to food production.

A dumpy woman with rosy cheeks and white hair met Kathleen at the door. She looked awkwardly at her, as if she didn’t quite know how to address her. ‘I’m Mrs Jones, the cook,’ she said, shaking Kathleen’s hand and half-curtseying at the same time. ‘I’ll take you up to yer room.’

‘Thank you,’ Kathleen replied, following the other woman into the house. She admired the magnificent entrance hall and the broad, sweeping staircase carpeted in red velvet. Kathleen had imagined the land girls would all bunk together in a barn, sleeping on bundles of hay, yet it sounded as if she was to have her own bedroom, right inside the grand house itself.

Kathleen’s room turned out to be at the very top of the building, and it was small but tastefully decorated. ‘You’ve got a lovely bathroom along here,’ Mrs Jones said, showing her into a large room with decorative tiles around the walls and the deepest bathtub she had ever seen. ‘Well, I’ll leave you to get settled,’ she told her.

‘Thank you,’ replied Kathleen. ‘Just one thing – where are all the other land girls?’

‘There ain’t none,’ the cook replied. ‘You’re the first we’ve had.’

Kathleen couldn’t help feeling disappointed. She had imagined herself making friends in the Land Army, going to dances with the other girls in the evenings and sharing confidences late into the night. Yet here she was, entirely on her own. It didn’t help that the servants seemed unsure how to treat her, since her status was somewhat unclear. She certainly wasn’t on the same level as the aristocratic family of the house, yet she wasn’t really one of the staff either.

That evening Kathleen’s dinner was sent up to her on a tray and she ate it alone in her room. But after she had finished, she decided to head downstairs and try to break the ice. In the basement she found the servants’ sitting room, where some of the maids were drinking tea. As she entered, they instinctively jumped to attention.

‘Oh, please don’t get up,’ Kathleen insisted. ‘I thought maybe I could join you for a while.’

The maids looked at her a little uncertainly, but one of them, a pretty ginger-haired girl a few years younger than Kathleen, gestured her towards a chair. ‘Course you can,’ she said. ‘I’m Minnie. How d’you do.’

Kathleen introduced herself and sat down opposite Minnie. ‘Do you play cards?’ the girl asked her.

Kathleen nodded.

‘How about Beat your Neighbour out of Doors?’

‘I’ve never heard of that one!’ Kathleen laughed.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll teach you,’ Minnie said, doling out the cards to Kathleen and the other girls. Soon they were all engrossed in the game, their former awkwardness forgotten.

Kathleen liked Minnie, and she soon discovered that the two of them had a lot in common. Minnie’s father had been stationed with the Army in India, just like Kathleen’s dad, and she had spent her early years living abroad.

As they played, Kathleen couldn’t help noticing that one of the other kitchen maids’ hands were badly disfigured, the fingers stuck together and the thumbs missing. ‘My mum fell off her bike when she were pregnant with me,’ the girl said, seeing her staring.

‘Oh, I’m sorry,’ Kathleen replied. ‘How awful.’

The girl shrugged. ‘Stopped me bein’ called up, though, so that’s somethin’.’

Mrs Jones wandered in from the kitchen. ‘You lot better let Miss Skin ’ere get to bed,’ she told the other girls. ‘She’s got to be up at ’alf five to help Mr Shaw, you know.’

Kathleen was shocked – that was even earlier than in her old job as a nanny. But there was no time to protest, as Mrs Jones gave her a candle to take up with her.

‘Oh, this arrived in the post for you,’ the cook added, handing her a parcel. ‘I reckon it must be your uniform.’

The next morning Kathleen was awoken by a knock on her door, and one of the maids came in with a cup of tea for her. It was still dark outside as she struggled into her new uniform – a fawn shirt, green V-neck pullover, brown corduroy breeches and long socks up to her knees. It was hardly a glamorous combination, but worst of all were the shoes – brown leather so hard that it felt like she was putting her feet into clods of iron.

Down in the kitchens Kathleen found Mrs Jones, who showed her the way to the gardens. Dawn was just beginning to break, and as Kathleen stepped outside she spotted a tiny old man with a bald head motioning to her to follow him. She guessed that the gnome-like figure must be Mr Shaw, the gardener.

The old man led Kathleen into an orchard of apple trees, where every spare inch of ground had been planted with vegetables. ‘Shu’ geh,’ he called back over his shoulder.

Kathleen looked at him blankly.

‘Shu’ geh,’ he repeated, more emphatically.

‘I’m sorry, what does that mean exactly?’ Kathleen asked, confused.

The little man walked slowly back over to the gate and pulled it shut behind her. ‘Shu’ geh,’ he repeated for a third time, clearly exasperated.

Mr Shaw hailed from Yorkshire and made no concessions to Southern ears like Kathleen’s. But as he showed her around the gardens, she realised he was a kind soul really. He had a daughter her age in the ATS, he told her, and he and his wife worried about her terribly.

Mr Shaw explained that thanks to the war he now grew everything from potatoes and turnips to broccoli, cabbages, kale, sprouts, carrots and mangold wurzels, all of which were sold at market in town. There were also apple, pear and plum trees, as well as bushes of gooseberries, raspberries and redcurrants. ‘Now, you jus’ do what ye can,’ he told Kathleen, handing her a spade and looking at her skinny frame uncertainly. ‘I don’t expect too much of ye.’

At Mr Shaw’s instruction, Kathleen set to work digging and planting, determined to prove to him that she was more than capable of the job she had been sent to do. But after an hour or so her brow was dripping with sweat and she felt ravenous.

She was relieved when, at eight o’clock, they stopped for a breakfast of porridge. ‘When do we finish for the day?’ she asked Mr Shaw.

‘Why, when t’sun goes down!’ the old man said, with a chuckle.

Soon they were back at work again, digging and hoeing away until at last Mrs Jones rang the bell for lunch. Kathleen took her meal on her own, while Mr Shaw headed back to the gardener’s cottage to eat with his wife.

By mid-afternoon Kathleen was utterly exhausted, but as Mr Shaw had promised there was no stopping until dusk fell. The vegetables had to be got ready for market on Monday, he told her, and with only a tiny old man and a skinny young girl to get it all done, it was going to be quite a task.

By the time Kathleen went up to her room that evening she was barely able to stand from the physical exertions of the day, and she woke the following morning feeling as if every muscle in her body had been pulled. It hurt just to walk down the stairs, but there was nothing for it except to head out to the gardens and start digging all over again.

The days at the grand estate passed excruciatingly slowly, and for Kathleen, who loved to talk and laugh, it was a lonely time. She was often left on her own for hours while Mr Shaw worked elsewhere in the grounds. Much of the time her only company was an old Suffolk horse called Patsy who, like the gardener, had seen better days.

One evening, Kathleen had just returned to her room to change out of her muddy clothes when there was a knock on her door. ‘Come in,’ she called, sitting down on the side of her bed.

Minnie came tumbling in excitedly. ‘You’ve been asked to go to dinner,’ she announced.

‘Where?’ Kathleen asked her, confused.

‘Here, with the family,’ the girl explained, grinning. ‘They want you to join them in the drawing room first – for sherry!’

‘Oh, right!’ Kathleen exclaimed. She hastily put on her only decent-looking dress and followed Minnie downstairs into the grand drawing room.

There, the lady of the house, Mrs Ashbourne, and her youngest daughter were waiting to receive her. The mother was a tall and elegant woman and her daughter was pretty, although Kathleen thought she looked rather tired.

‘So, you’re our new land girl,’ Mrs Ashbourne said, eyeing Kathleen with interest. ‘How delightful. And how is old Shaw treating you – not too roughly I hope?’

‘Not at all,’ Kathleen answered. ‘He’s been very kind.’

‘I’m so glad,’ the lady continued. ‘My daughter Jane here works as a nurse in the local hospital, you know. It’s terribly hard work, but the young must do their bit for the war, I suppose.’

Jane looked up and gave Kathleen a feeble smile.

Looking around the room, Kathleen saw that it was hung with a number of old oil paintings depicting the family’s ancestors. Mrs Ashbourne was delighted to talk her through them all, introducing each long-departed family member one by one. From what Kathleen could gather, the Ashbournes, along with most of the other wealthy families in the area, were Quakers. They had all made their money in manufacturing, and by now they had intermarried pretty thoroughly.

At dinner, however, it was Kathleen’s family that was the object of conversation. The Ashbournes had never had anyone like her sit at their table before, and they were fascinated by every detail of her life when she was growing up. Story-telling was Kathleen’s forte, and she warmed to the task, entertaining them with tales of her parents’ romantic meeting in Cape Town and the struggles they had faced coming back to England, where they had survived on the rabbits they caught and skinned for dinner. The whole family hung on to her every word – in fact, the only difficulty she faced was trying not to giggle when the servants she had been playing cards with the night before winked as they served her potatoes.

After dinner, Kathleen snuck back down to the basement for a cup of tea with the maids and listened to them gossip about the family. ‘They’ve got 12 children, you know, and at least two of them are doolally,’ Minnie told her.

‘They say the Ashbournes are running out of money,’ the girl with the deformed hand chipped in. ‘It was all invested overseas, and now they can’t get it ’cos of the war.’

‘And as for that Jane,’ the head housemaid, a woman of about 40, added, ‘I’ve heard she’s in love with one of the wounded soldiers she’s been treating down at the hospital – and it turns out he’s a lorry driver in Civvy Street!’

‘Ooh, I don’t think madame would be too pleased about that!’ declared Minnie. The group of women laughed together until their sides ached.

Kathleen enjoyed the chance to join in with the servants’ gossiping, but she soon discovered that the head housemaid had a romantic secret of her own. That night, when Kathleen tiptoed down to the kitchen to fetch herself a glass of water, she found the woman perched on the kitchen counter with her legs wrapped around the postman.

Kathleen gasped, and the couple sprang apart in embarrassment. As the postman hastily picked his trousers up off the floor, she backed out of the room, blushing, and fled up the stairs.

Kathleen’s own love life was continuing as well as could be expected with her boyfriend hundreds of miles away up in Scotland. She and Arnold continued writing to each other regularly, and she kept him up to speed with all the strange goings on at the grand house. But it wasn’t long before she had a new and entirely unwanted admirer to deal with.

The fields neighbouring the Ashbournes’ estate were owned by a young farmer who had recently inherited them from his father. He had several land girls working for him already, but when one of them fell ill he asked Mr Shaw if he could borrow Kathleen for the day to help harvest his Brussels sprouts.

‘Aye, ye can ’ave the girl,’ the old man replied, ‘but only if ye promise not to overwork her. The poor lass is thin as a rake, you know!’

Kathleen set off, happy for a change of scene and hoping to get to know some of the other land girls. But she soon discovered she would be spending the day all alone in a ten-acre field, her only visitor being the farmer. The young man took a keen interest in the flame-haired girl who was picking his sprouts, and stopped to stare at her whenever he passed by on his tractor.

It didn’t take long for him to find an excuse to come and talk to her. ‘You be a pretty little thing to be getting your hands so muddy,’ he remarked admiringly.

‘Oh, I don’t mind,’ Kathleen replied, carrying on with her work.

‘Got a boyfriend, have you?’ the man asked her.

‘Yes, I have,’ said Kathleen, firmly.

‘That be a shame,’ the man told her wistfully. ‘I been looking for a wife to run this ’ere farm wi’ me.’

Kathleen said nothing, and eventually the man went away. But over the next few weeks he kept asking Mr Shaw if he could ‘borrow’ her again. The young man was clearly lonely and longed for someone to share his days with, but Kathleen soon grew sick of him pestering her.

One day, the young farmer took Kathleen with him into Bury St Edmunds, where he had some errands to run. She sat in the passenger seat of his van, wrapped up in her own thoughts and doing her best to avoid conversation.

Suddenly there was an almighty crash as the van collided with another vehicle. Kathleen was thrown from her seat and her head smashed straight through the windscreen, lodging there as the van came to a halt. Her neck was completely surrounded by glass, and it was cutting painfully into her skin. If she moved even an inch, she was sure it would sever an artery.

Before long the police were on the scene, carefully dismantling the windshield around Kathleen’s head and freeing her from the prison of glass. She was rushed to the local hospital, where her cuts were bandaged up, but the accident left her with a ring of tiny scars around her neck.

Before long, the case came to court, and Kathleen was called as a witness. The young farmer was claiming that the other vehicle had come out of nowhere when he hit it, and she was asked what she remembered of the incident.

‘I’m sorry, but I can’t help you,’ she replied. ‘I just don’t remember a thing.’

‘You must have seen what happened,’ the magistrate protested. ‘You were sitting right up in the front!’

But Kathleen had been so busy daydreaming that she had no recollection of anything before the moment her head hit the glass.

The young farmer was duly fined for dangerous driving, and after Kathleen’s failure to corroborate his account, he never asked her to pick his sprouts again. It was scarcely the easiest way to free herself from his unwanted advances, but it seemed to have done the trick nonetheless.

It was many months now since Kathleen had last seen Arnold, but his letters had kept her going through the long, hard days on the land. At last, when she went home to her mother’s house in Cambridge for some leave, he was able to join her for a day. To Kathleen he seemed even more charming than she remembered, and her feelings for him were stronger than ever before.

Mrs Skin did everything she could to make her daughter’s handsome officer welcome, using up an entire week’s rations on a single magnificent meal. But it was when she finally went out on an errand that Arnold revealed the true purpose of his visit. ‘My darling,’ he said breathlessly, taking Kathleen in his arms, ‘you know we belong together. Will you marry me?’

Kathleen felt as if her heart could have burst then and there. ‘Yes, of course!’ she cried, falling into his embrace.

Arnold drew a little box out of his pocket and handed it over to her. Inside was the most beautiful ring that Kathleen had ever seen, set with a stone of yellow citrine. He tried to push it onto her finger, but to her disappointment it just wouldn’t fit. ‘Oh dear,’ he murmured. ‘I suppose we’re going to have to get it altered.’

‘No – don’t take it away,’ Kathleen pleaded. ‘I’ll wear it around my neck on a chain. That way it’ll always be with me when we’re apart.’

Kathleen hoped it wouldn’t be long before the two of them could be married, but to her surprise Arnold told her that he wanted to wait until the war was over. ‘I’ll never forget the woman who used to wash our steps and windows,’ he told her. ‘She had been wealthy once, but when her husband was killed in the last war she was left with two young children to support by herself. I wouldn’t want that to happen to you, my dear.’

‘Yes, of course, you’re right,’ Kathleen replied, trying to hide her disappointment. If it was up to her, she would have married Arnold then and there, but she was willing to abide by his decision.

After Arnold had left, Kathleen showed her mother the ring. ‘I knew it!’ Mrs Skin declared, ecstatically. ‘I just knew that you’d be married before the year was out! Oh isn’t he wonderful, Kath. What a lovely man you’ve found yourself! I’d better start seeing about your trousseau.’

‘We’re not getting married until after the war, Mum,’ Kathleen protested weakly. But it was no use reasoning with her mother. Mrs Skin was already off to tell all her friends, and gather material for her daughter’s bottom drawer.

Chapter 3 (#ua35f24a4-f596-5fbf-9936-81576f15535f)

After many months in the Land Army, Kathleen’s body had gradually grown stronger and more resilient as she adapted to the rigours of 12-hour days working the land. Now she was determined to try again with the Navy, so she said her goodbyes to Minnie and the rest of the staff in the strange old house at Bury St Edmunds, and took a train down to London. There she made her way to the national headquarters of the WRNS, which was housed above Drummond’s Bank in Trafalgar Square.

But despite her best efforts to convince the women there that she was just what the service needed, they insisted that there still wasn’t a place for her. ‘I’m sorry,’ one of them told her, ‘but we’ve just got too many people volunteering at the moment. Maybe you could try again in another six months.’

Kathleen was disappointed at being turned down by the WRNS for a second time, and it was especially galling to think that while she had been waiting to reapply, other girls had taken the available places. But she couldn’t bear the thought of heading back to the house in Bury with her tail between her legs, so instead she began looking for war work in London.

Before long, Kathleen had swapped the jumper and breeches of a land girl for the blue overalls of an ambulance auxiliary. It was far from the high couture of the tailored Wren uniform that she had long coveted, but at least, she reasoned, the new job would bring with it different challenges – and, hopefully, less back-breaking work.

Since she didn’t drive, Kathleen was paired up with a girl who did – a young woman called Hilde with whom she was soon sharing a small flat in Chiswick. The two girls hit it off instantly, and when Kathleen learned Hilde’s sad story it only cemented the bond. ‘My husband walked out as soon as he found out I was pregnant,’ Hilde confided one evening, explaining that her daughter Joy was now living with a family in the countryside while she worked on the ambulances to support her.

Hilde and Kathleen’s ambulance – in reality a converted van – was based at the offices of United Dairies in Chiswick, a location they came to know extremely well as they spent night after night there sitting around waiting for the phone to ring. The other volunteers included several members of the same family, who had all volunteered together and were all actors. Kathleen and Hilde soon grew used to being hugged and kissed effusively whenever they came into the office, and to being addressed exclusively as ‘darling’. More of a trial were the histrionic rows between the father and his eldest daughter, which seemed to erupt on a daily basis and frequently descended into furious swearing matches.

On the whole, though, it was a quiet time for the men and women working on the ambulances. Since the London Blitz had come to an end in May 1941, German attacks on the capital had grown increasingly infrequent, limited to the occasional ‘nuisance raids’ on targets of no military significance. But while they might be little more than a nuisance as far as winning the war was concerned, these small, sporadic attacks could be deadly for the poor souls caught up in them.

The first time Hilde and Kathleen were called out, it was to a pub in Hammersmith which had suffered a direct hit. They hopped in their little van and sped over as quickly as possible, reaching the bombsite within ten minutes.

By the time the girls arrived, there were plenty of other people already on the scene. ‘No point going in there,’ a Special Constable told Kathleen, as she gazed in horror at the pile of rubble where only minutes before the pub had stood. ‘There were a load of troops in the cellar when it hit. The pipes down there burst and the lot of them drowned before we could get them out.’

As the policeman turned and walked off into the darkness, Kathleen became aware of a dog barking somewhere nearby. She followed the sound to a house adjacent to the pub, which had also been badly damaged. Most of the front wall had come down, and Kathleen walked through a space where the door had once stood into what was left of the living room.

Inside she found a black-and-white sheepdog, which by now was howling plaintively, a few feet away from the body of an old man who was evidently its master. ‘It’s all right,’ she told the distraught animal, in as calm a voice as she could manage. She didn’t dare reach out a hand to stroke it, in case it lashed out and bit her in fear.

Kathleen continued to make cooing noises at the dog while she knelt down to examine the old man. He was alive, but only just. A large part of his face had been blown off by the explosion, and his breathing was shallow. She could tell at once that he had no chance of surviving his injuries.

Kathleen took a towel and wrapped it around the man’s head. Then she sat on the floor, gently cradling him, all the while whispering to the frantic dog, ‘It’s all right, don’t worry, it’s all right.’

Within a couple of minutes the last spark of life had departed and Kathleen set the man’s lifeless body down on the floor. Then she went to summon Hilde, and between them they heaved him onto a stretcher and carried him out to their ambulance.

As they drove away, she could still hear the poor dog howling, rooted to the spot in the room where its master had died.

The bomb had left no survivors for the girls to transport to the local hospital, so instead they drove straight to Hammersmith Cemetery, where a man on the gate directed them towards the mortuary. There were so many bodies coming in that night that the building was already full, and as the corpses arrived they were being laid out on the pavement outside. Kathleen tried not to look at the faces, but she couldn’t help noticing that many of them had been terribly disfigured and some bodies were missing arms or legs.

By the time Kathleen and Hilde had got the old man out of the ambulance and laid him out alongside the other victims of the night’s raid, their shift was coming to an end. They returned the ambulance to the United Dairies offices, and trudged back to their little flat. It was only once they were on their way home that the horror of the evening overcame them, and they both had to stop and vomit by the side of the road.

As the weeks and months went on, Kathleen and Hilde grew accustomed to the horrors of the air raids. Collecting severed arms and legs in an old tarpaulin and matching them up with dead bodies they had found became routine, as did braking suddenly when huge craters appeared in the middle of the road in front of them. They got used to sleepless nights and uneaten meals, and to frequent stops to throw up in the gutter.

Some of the girls’ call-outs were almost surreal. One night they arrived at a house that had been ripped open by the blast from a bomb, only to find a woman sitting naked in a bath on the first floor, fully exposed to the street below. She was covered in blood from head to foot, and was screaming hysterically as a fireman climbed up a ladder to bring her down.

Although the work Kathleen was doing was emotionally draining, living in the capital did have its advantages, as it meant that she was able to meet up with Arnold from time to time. His parents lived in Clapham and he came down to London to visit them whenever he had leave.

Kathleen’s dashing fiancé certainly knew how to show a girl a good time, and would wine and dine her in the smartest establishments he could find. One night they went to see a Polish orchestra perform at the Royal Albert Hall; another they took in a play on Shaftesbury Avenue. Arnold even took Kathleen to the famous Windmill Theatre in Soho, where they gawped at the tableaus of naked women.

As time went on, however, the horrors of working on the ambulances took their toll on Kathleen, and when an opportunity arose to take on some slightly less distressing employment, she decided that the time had come for her to leave. Her mother had heard that the hospital she worked at in Cambridge was looking for nursing auxiliaries, and suggested that Kathleen should join her there. ‘You could live at home and save money on the rent,’ she pointed out.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/calvi-18527013/kathleen-s-story-heroism-heartache-and-happiness-in-the-war/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Duncan Barrett и Calvi

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the bestselling authors of The Sugar Girls and GI Brides, this is Kathleen’s story, one of three true accounts from the book The Girls Who Went to War.“Boxing Day was cold and frosty, and by the time Kathleen and the lads arrived at the football pitch she was already shivering. As they stood watching the game, Arnold silently took her hand and put it inside the pocket of his greatcoat. It was a small gesture, but it told her that she belonged to him now, and to Kathleen nothing had ever seemed so romantic.”In the summer of 1940, Britain stood alone against Germany. The British Army stood at just over one and a half million men, while the Germans had three times that many, and a population almost twice the size of ours from which to draw new waves of soldiers. Clearly, in the fight against Hitler, manpower alone wasn’t going to be enough.Nanny Kathleen Skin signed up for the WRNS, leaving her quiet home for the rigours of training, the camaraderie of the young women who worked together so closely and to face a war that would change her life forever.Overall, more than half a million women served in the armed forces during the Second World War. This book tells the story of just one of them. But in her story is reflected the lives of hundreds of thousands of others like them – ordinary girls who went to war, wearing their uniforms with pride.