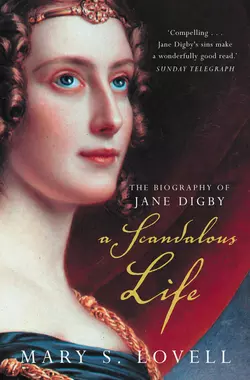

A Scandalous Life: The Biography of Jane Digby

Mary S. Lovell

The biography of Jane Digby, an ‘enthralling tale of a nineteenth-century beauty whose heart – and hormones – ruled her head.’ Harpers and QueenA celebrated aristocratic beauty, Jane Digby married Lord Ellenborough at seventeen. Their divorce a few years later was one of England s most scandalous at that time. In her quest for passionate fulfilment she had lovers which included an Austrian prince, King Ludvig I of Bavaria, and a Greek count whose infidelities drove her to the Orient. In Syria, she found the love of her life, a Bedouin nobleman, Sheikh Medjuel el Mezrab who was twenty years her junior.Bestselling biographer Mary Lovell has produced from Jane Digby’s diaries not only a sympathetic and dramatic portrait of a rare woman, but a fascinating glimpse into the centuries-old Bedouin tradition that is now almost lost.Note that it has not been possible to include the same picture content that appeared in the original print version.

A Scandalous Life

The Biography of Jane Digby

MARY S. LOVELL

Dedication (#ulink_c808121a-322f-5083-8655-727cab483b5f)

This book is dedicated to

Joan Williams

to whom I owe a great deal;

she knows why.

And also to my aunt

Winifred Wooley

who is a great lady.

Epigraph (#ulink_cfb72873-931f-5638-b397-d340bffe4853)

‘How could this Lady Ellenborough, whose scandalous life is known to all the world, have deceived you, Your Majesty?’

Letter to King Ludwig I from his mistress’s maid

Contents

Cover (#u52fa003e-24d5-5775-aa73-86d405c5b320)

Title Page (#u8c41e273-aa0a-5307-b164-462f3209827e)

Dedication (#u697656ee-707e-5bfe-be93-cf2aa5e68289)

Epigraph (#u000d076d-87cf-5e09-8f6b-ff8fff3cd922)

Preface (#u7c8776f1-a1b2-588c-b14e-e41df01620d7)

1 Golden Childhood 1807–1823 (#ueaa65fa6-a78c-5340-bfba-7b7dcfcdeb58)

2 The Débutante 1824 (#u89031b75-c939-5cdd-a2de-e200d71b28c8)

3 Lady Ellenborough 1825–1827 (#u5264b6e9-2933-5537-80c9-19852cf80fdb)

4 A Dangerous Attraction 1827–1829 (#u2db4a2b4-8ed7-5dd4-b283-2bf5252d8c31)

5 Assignation in Brighton 1829–1830 (#u7b454ab9-fceb-5ac6-836c-7e0628c91683)

6 A Fatal Notoriety 1830–1831 (#u798432fe-551b-5705-8349-c5c26d2cc133)

7 Jane and the King 1831–1833 (#u84391eee-9480-5894-9e87-5de735326a0e)

8 Ianthe’s Secret 1833–1835 (#litres_trial_promo)

9 A Duel for the Baroness 1836–1840 (#litres_trial_promo)

10 False Colours 1840–1846 (#litres_trial_promo)

11 The Queen’s Rival 1846–1852 (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Road to Damascus 1853 (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Arabian Nights 1853–1854 (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Honeymoon in Palmyra 1854–1855 (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Wife to the Sheikh 1855–1856 (#litres_trial_promo)

16 Return to England 1856–1858 (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Alone in Palmyra 1858–1859 (#litres_trial_promo)

18 The Massacre 1860–1861 (#litres_trial_promo)

19 Visitors from England 1862–1863 (#litres_trial_promo)

20 The Sitt el Mezrab 1863–1867 (#litres_trial_promo)

21 Challenge by Ouadjid 1867–1869 (#litres_trial_promo)

22 The Burtons 1870–1871 (#litres_trial_promo)

23 Untimely Obituary 1871–1878 (#litres_trial_promo)

24 Sunset Years 1878–1881 (#litres_trial_promo)

25 Funeral in Damascus 1881 (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix: Last Will and Testament of the Hon. Jane Digby (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

By Mary S. Lovell (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Preface (#ulink_e36c2ebc-5301-5c69-970a-f0ba203e87a4)

Friends often ask me how I choose my subjects. The answer is that my subjects usually choose me, and so it was with Jane Digby.

This book began at a cocktail party at the RAF Club in London in the spring of 1992 when Jane Digby’s name and her story came up in conversation. I had never heard of her, so I made a mental note to do some research and rapidly found myself in the early stages of an obsession that was to last several years. Who was Jane Digby, and why should she cast such an appeal?

Born into the English aristocracy with every conceivable advantage in physical beauty, social position and wealth, Jane spent the final years of her life married to a desert prince. The Palladian mansions and gilded Mayfair salons of her youth made way for low black goat-hair tents and rugs spread upon wind-washed sands. Even now, with jet travel and motorised transport, the Syrian desert is one of the few lonely places left on earth. What unlikely circumstance, I wondered, had led Jane Digby there a century and a half ago?

Barely out of the schoolroom, already regarded as one of the most beautiful women of her day, Jane had married an ambitious politician, Lord Ellenborough, who was twice her age. In achieving his desire for a Cabinet post, Ellenborough neglected his bride and she soon sought consolation elsewhere. Before she was twenty-one Jane’s love affair with an Austrian prince precipitated her into one of the most scandalous divorce cases of the nineteenth century. In April 1830, to the astonishment of its readers, The Times cleared its traditional front page of classified advertisements to carry a sensational news story – a verbatim report of the Ellenborough divorce hearing in Parliament which included intimate details about the beautiful peeress and her prince.

Jane did not dispute the charges. Head over heels in love, she had already run off to Europe. But her story did not end there. Subsequently, for over twenty years Jane was to have a number of love affairs with members of the European aristocracy including a German baron, a Greek count and the King of Bavaria, as well as an Albanian general from the mountains. During this time she also married twice and travelled from the royal courts of Europe to the wilder regions of Turkey and the Orient. After a succession of scandals and betrayals, she made a journey to Syria. By then she was almost fifty and feared her life was over. Astonishingly, the most exciting part of her story still lay ahead of her.

The Arab nobleman who had been engaged to escort her caravan to the ruined city of Palmyra fell in love with her. He was young enough to be her son, was of a different culture and already had a spouse; indeed, he had recently divorced a second wife but he asked Jane to marry him. Although she was doubtful at first, she was soon deeply in love and, ignoring the entreaties of British officials, placed herself willingly in the power of a man who could divorce his partners on a whim. Sheikh Medjuel el Mezrab was the love of her life, and he brought her all the romance and adventure she had ever dreamed of.

Inevitably, because of the years she spent in Arabia, Jane’s story invites comparisons with that of Lady Hester Stanhope, the niece and confidante of William Pitt who became the self-styled ‘Queen of the Desert’ a generation before Jane. But Hester Stanhope ended her life in Syria in abject poverty as an eccentric recluse, robbed, abused and eventually deserted by her Arab servants. Jane Digby lived as a respected, working leader of her adopted tribe, spending months at a time in the Baghdad desert, sharing the spare existence of the bedouin.

So astonishing was Jane Digby’s career to her contemporaries that no fewer than eight novels based on her character and various elements of her story were written during her lifetime – one for every decade of her life. From 1830 until her death in Damascus in 1881 her name was rarely out of the newspapers as she featured in one outrageous tale after another.

Was it possible, I wondered when I embarked upon this project, to discover the rationale of such a person who even as a young woman married to an eminent Cabinet Minister refused to concede to convention by hiding her illicit love affair? Who a century ahead of her time was completely free of any form of racial or cultural prejudice? Who saw travel to exotic destinations as a raison d’être second only to sharing her life with a great all-encompassing love (though she showed remarkably little regard for the immense difficulties involved in both)? Who had, even prior to her desert expeditions, carelessly abandoned the comfortable life of a royal mistress to live with an Albanian chieftain who was virtually a legitimised brigand?

Over a hundred years had elapsed since her death, but I knew that, in common with many contemporaries, Jane kept diaries all her life. Her first biographer, E. M. Oddie, who wrote A Portrait of Ianthe in 1935, had access to some of them; but several subsequent biographers (such as Lesley Blanch and Margaret Schmidt) declared that the diaries were lost. Since E. M. Oddie had quoted from the diaries hardly at all, this seemed especially tragic. So I set out to discover what had happened to them in order to learn about Jane through her own voice. I also decided to try to locate the diaries and correspondence of people who met or were friends with Jane, not only to see what more could be learned about her, but to give a three-dimensional perspective to her story.

I contacted Lord Digby, a direct descendant of Jane’s brother, Edward, and in April 1993 at his invitation I drove down to Minterne House in Dorset one morning to see his collection of Jane’s watercolours. Over lunch I told him about my work and, after a pause, he looked at me, seemed to come to a decision, and said, ‘Um, we do have Jane’s diaries here. But we’ve never shown them to anyone.’

Within a short time I was seated at a writing table with objects that had once been Jane’s; her notebooks and sketchbooks, and her diaries which covered more than three decades, principally those years she spent in the desert. All would need to be transcribed and indexed to be easily accessible. Some sections written in pencil were badly faded; many entries were written in code and there were passages written in French and Arabic. I realised too that the code, once broken, might translate into any of the many languages that Jane spoke; it would be a mammoth task. Five days later I was due to leave for Syria to research Jane’s life there. I asked to be allowed to return to Minterne at some date in the future for a very long time.

Somewhere there must be a patron saint of biographers, to whom I owe much. On my second visit Lord Digby showed me a small portrait of Jane which hangs in the great hall at Minterne. ‘We believe from portraits that she had the same colouring as my sister Pamela … we’ve always thought they were probably quite alike.’ The Hon. Pamela Digby, later Mrs Randolph Churchill and now US Ambassador Mrs Averell Harriman, shares a great deal with Jane: intelligence and charm, an unselfconscious sexuality, a disregard of the mores that accept (even admire) polygamy in men but deprecate similar behaviour in women. Mrs Harriman is widely regarded as a nonpareil among US Ambassadors to France and her ability to attract and fascinate is as legendary as that of her ancestor. Several portraits of Jane bear a remarkable likeness to Pamela Digby Harriman.

One memorable day I received a package from a descendant of Jane’s brother Kenelm, a branch of whose family moved to New Zealand some decades ago. It contained letters written by Jane to her family and others over a thirty-year period. Together with her diaries and other papers, they provide a unique insight into a remarkable life.

During my trip to Syria I encountered the seductive spell of the desert that so bewitched Jane. With the enthusiastic help of my guide and interpreter Hussein Hinnawi, I was able to locate the remaining traces of her residence in Damascus; her home with its celebrated octagonal drawing-room and the high cupola ceiling, its curved alcoves for books and china, and its treasury of gilded woodcarving; her grave and – not least – Jane’s lingering legend. Even after I left Syria, Hussein continued to research the story, purely out of interest, and his contribution to this book has been invaluable.

Had I simply copied all the information amassed during research, including relevant excerpts from over 200 books and scores of newspapers, parliamentary records, Jane’s own diaries, letters and sundry papers, and those of her many friends such as Lady Anne Blunt, Isabel Burton and Emily Beaufort, the result would have been many thousands of pages of text. However, the job of a biographer is not merely to unearth and assemble facts; one must also dissect, compare, confirm and analyse; then hone the result in order to present to the reader a historically accurate, digestible and, I hope, enjoyable account of the subject.

Here, then, is my portrait of Jane Elizabeth Digby.

I Golden Childhood 1807–1823 (#ulink_5a1bc575-ec6b-5852-8b66-7428f616670d)

When Jane Elizabeth Digby was born at Forston House in Dorset on 3 April 1807 her parents had hoped for a son. However, she was such a beautiful child that her family were soon besotted with her. After all, there was time for sons and, as Jane’s aunt wrote, ‘providing the little girl is well and promising we must not hold her sex against her’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Later, with her large violet-blue eyes and pink-and-white complexion, little Janet (as her family called her then) was a pretty sight. Her waist-length golden hair, curling free from the prescribed banded and ringleted style, glistened halo-like in the sunshine. Her cheeks glowed: ‘a picture of health,’ local villagers said. As curious and agile as a kitten, as intelligent and eager as a puppy, she seemed to want to take the world by the coat-tails, and there was about her, even then, an irresistible charm.

This alert vitality captivated her grandfather, who was called ‘Coke of Norfolk’ throughout the country and ‘King Coke’ by everyone in Norfolk. Widely regarded as the most important and powerful commoner in England, Thomas Coke might have had a peerage for the asking; indeed, King George III was eager enough to bestow one. Yet this would have meant Coke giving up his independence and his seat in the House of Commons where he represented the county of Norfolk. He saw no merit in doing so.

Thomas Coke had three daughters, Jane, Anne and Elizabeth. They were all acknowledged beauties and all well educated; his late wife had seen to that when it became obvious there would be no male heir.

(#litres_trial_promo) In addition to these advantages, Mr Coke had dowered his girls generously so that their eligibility in the marriage market was assured, though, in the event, all three married for love.

(#litres_trial_promo) Since their sex prevented them from inheriting a title from their father, he therefore resisted ennoblement – once to the extent of openly rebuffing the King – spoke his mind freely and often bluntly, and owed allegiance to no man he felt had not earned his respect.

Coke’s home in Norfolk was Holkham Hall, a Palladian mansion more like a palace than the home of a country squire. Here, in the great house where her mother had grown up, Jane spent much of her childhood.

Jane’s mother, Thomas Coke’s eldest daughter Jane, was known as Lady Andover, a form of address she used for the remainder of her life. The title was retained from a previous (childless) marriage which had ended in tragedy when she was twenty-one. Her husband Lord Andover had been killed as the result of a shooting accident that she had accurately foreseen in a dream. She had rushed out to him upon hearing the news, and almost his last words to her were: ‘My dear, your dream has come true!’

(#litres_trial_promo) It was not her only successful prediction and, curiously, her second husband had a similar ability, claiming that he owed his first success to a voice in a dream which told him to change the direction in which his ship was headed and even the course to steer.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Captain Henry Digby, Jane’s father, was a fair, handsome and much decorated naval hero. Prior to his marriage to Lady Andover he had distinguished himself at Trafalgar as commander of HMS Africa. In a letter to his uncle, the Hon. R. Digby (later Lord Digby), at Minterne he wrote of his part in the battle:

HMS Africa at sea off the Straits November 1, 1805

My dear Uncle,

I write merely to say I am well, after having been closely engaged for 6 hours on 21st October. For details, being busy to the greatest degree, I have lost all my masts in consequence of the action and my ship is otherwise cut to pieces but sound in the bottom. My killed and wounded number 63, and many of the latter I shall lose if I do not get into port …

After passing through the line in which position I brought down the fore masts of Santisima Trinidad mounting 140 guns, after which I engaged with pistol shot L’Intrépide 74 guns, which afterwards was struck and burnt, Orion and Conqueror coming up. A little boy that stayed with me is safe. Twice on the poop I was left alone, all about me being killed or wounded. I am very deaf.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Before Trafalgar he had been posted aboard the frigate Aurora and in less than two years had captured six French privateers (thanks to the voice in his dream) and one corvette, L’Egalité, making a total of 144 guns and 744 men, besides 48 merchant ships taken or sunk. In command of the Leviathan he assisted in the capture of the island of Minorca. Later he captured two French men-of-war, Le Dépit and La Courage; and in 1799 two Spanish frigates Thetis and Brigide, which carried between them 3 million dollars in gold. Fifty military wagons were needed to convey the spoils from Plymouth Dock to the Citadel. By the time he was thirty, Captain Digby had earned himself over £57,000 in prize money alone, and another £7,000 over the next five years.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At the time of Jane’s birth Captain Digby owned Forston House, a pleasant country property in Dorset. It overlooked the famous Cerne Abbas giant and was close to his uncle’s estate, Minterne. It was because of her father’s frequent absences at sea, and her mother’s natural wish to spend time ‘at home’ at Holkham while he was away, that Jane and her two younger brothers, Edward and Kenelm, were often at their grandfather’s house and, like their mother, came to regard Holkham as a second home. Here the eleven children of Lady Andover’s sister Anne and her husband, Lord Anson, were also educated in the capacious schoolroom. Jane was particularly close to her Anson cousins Henry and Fanny who were nearest to her in age.

Those first decades of the nineteenth century were a golden era for the rich. Vast country houses surrounded by shaved lawns and pleasure gardens, with artificial lakes, follies and deer parks, stables full of hunters, hacks and work-horses, and coach-houses full of elegant equipages, provided work and livings for hundreds of servants indoors and out. Holkham was no exception.

Tom Coke could not be described as extravagant; he spent shrewdly enough, but no visitor ever walked through the deliberately unpretentious front entrance of Holkham Hall without being stunned at what lay within. The massive entrance hall, modelled on a Roman temple of justice, is an extravaganza of marble, alabaster and carved stone. Fluted Ionic columns support the domed Inigo Jones roof, a gilded crown for this masterpiece of light and space. Around the walls are bas-relief and marble sculptures, and the classical theme continues throughout the house. Holkham was – and remains – richly endowed with Greek and Roman statuary, but it is also famous for its art collection, its rich and rare furnishings and sumptuous Genoese velvet hangings, and its incomparable library. It is still regarded, along with Chatsworth, Blenheim, Badminton and Burghley, as one of the truly great houses of England.

Such grandeur, however, was not the brainchild of Jane’s grandfather. The property was bought in 1610 by Edward Coke, the famous jurist, who became Lord Chief Justice. The first Earl of Leicester built the present house in 1734 and, when the direct line failed, the estate, but not the title, passed to Thomas William Coke. If Thomas Coke ever was inclined towards prodigality, the money was spent on his lands rather than his house. Politically he was a staunch Whig, but first and foremost he was a dedicated agricultural reformer, who spent a fortune

(#litres_trial_promo) transforming a rugged wasteland ‘where two rabbits fought over a single blade of grass’ into a fertile, productive, ‘scientifically controlled’ region famous for its barley soil.

(#litres_trial_promo) He convinced men of substance to invest in long-leases of farms and to ‘induce their sons, after [reading] Greek and Latin in public schools, to put themselves under the tuition of well-informed practical farmers to be competent for management.’

(#litres_trial_promo) It is no exaggeration to say that this far-sighted man was the architect of modern farming methods throughout the world.

His livestock, particularly sheep, were selectively bred for meat, breeding stock and wool. His annual sheep-shearing, known as Coke’s Clippings, became a sort of four-day county fair which attracted thousands of sightseers from all over the country, and overseas. Exhibitions of every aspect of rural industry, from animal husbandry to flax weaving and the building of agricultural cottages, were presented. Conferences were held during which papers were given on agricultural matters such as crop rotation and stock-breeding, and these were a magnet for the guests assembled at Holkham for the Clippings, almost all of them titled.

(#litres_trial_promo) The autumn and winter shooting parties at Holkham included royalty and top political figures of the Whig Party, as well as sporting squires, and Mr Coke’s hospitality was legendary.

Despite his leaning towards outdoor pursuits, Thomas Coke did not neglect the arts. Educated at Eton (where on one occasion, to avoid being caught poaching on the neighbouring royal estates, he swam the River Thames with a hare in his mouth),

(#litres_trial_promo) he spoke both Greek and Latin. He inherited the vast library of classical literature and manuscripts at Holkham, considered to be a national treasure (when he took over Holkham he found hundreds of rare books from Italy still unpacked in their crates), but he continued throughout his life to purchase rare books, and works of art by such contemporary geniuses as Gainsborough, to add to those by Titian, Van Dyck, Holbein, Rubens and Leonardo da Vinci.

It was in this atmosphere that Jane spent much of her youth. She was encouraged by her grandfather to ride, to take an interest in the active management of horses and small farm animals, to read the classics and to be aware of the ancient civilisations represented at Holkham, as well as modern politics. She lived the privileged life of a cosseted only daughter, surrounded on all sides by love and admiration, and the constant companionship of her two brothers and numerous cousins. In turn she worshipped her hero father, adored her lovely mother, who was called by all three children ‘La Madre’, and loved and revered her aunts.

We have mere glimpses of Jane in those days. A family friend who peered round the door of an upper-floor room saw through the dust motes of an early summer morning that ‘the schoolroom was nearly full … there was Miss Digby – so beautiful – and the two Ansons, such dear and pretty children’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Another noted Jane’s vitality and grace of movement, but judged that ‘her chief glory was her hair, which fell, a rippling golden cascade, down to her knees.’

(#litres_trial_promo) An aunt recollected that as a child Jane used to refer to annoying incidents with the impatient phrase, ‘it is most provocative and bothersome.’

(#litres_trial_promo) In later years, Jane’s own diary recalls the wonderful, rumbustious, ‘old-fashioned’ Christmases at Holkham, with all the traditions of feasting and mummers and laughter and games, and the annual servants’ party. We also know from the diaries of her relatives, and visitors to Holkham, of the gargantuan dinners of dozens of courses for scores of appreciative diners from the Prince of Wales (a frequent visitor before he became Regent) to scholars, to which the children were sometimes invited. Again, we learn from her own diary that Jane’s chief delight was to beat her brothers in their frequent mock horse-races.

(#litres_trial_promo) She had no time for dolls and girlish toys but preferred riding and playing with dogs and the numerous family pets.

(#litres_trial_promo) Totally fearless, she could ride anything in the Holkham stables, and was as at home looking after a sick beast as riding one – which must have especially endeared her to her grandfather.

That she was frequently wilful is enshrined in family legend, as is the further characteristic that she was so prettily mannered and always so abjectly apologetic at having offended that she was instantly forgiven. It was a happy childhood, but her natural high spirits led her into many ‘scrapes’, as she called them, and a picture emerges of a highly intelligent, active, perhaps somewhat spoiled little girl who instinctively threw up her head at any attempt to check her. She was not unfeeling in her pranks, however; her anxious cajolery shines through the tear-stained and ink-blotted note of apology that she wrote to her mother at the age of about eight:

Dearest Mama,

I am very sorry for what I have done and I will try, if you will forgive me, not to do it again. I wont contradict you no more. I’ve not had one lesson turned back today. If you and Papa will forgive me send me an answer by the bearer – pray do forgive me.

You may send away my rabbits, my quails, my donkey, my monkey, etc., but do forgive me.

I am, yours ever,

JED

P. S. Send me an answer please by the bearer. I will eat my bread at dinner, always.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was perhaps hardly surprising that Jane was a beauty. Her looks were inherited from her maternal grandmother – a woman of almost fabled loveliness and charm. Jane’s mother was herself described by the Prince Regent as ‘without doubt, the handsomest woman in England’.

(#litres_trial_promo) However, it was unusual that Jane was given the same education as her brothers and male cousins, so that in addition to the practical basic education which naturally included French, a little German and Italian and a knowledge of the arts, she also had a thorough grounding in classical languages and acquired a love of history both ancient and modern. Nevertheless she managed to emerge from the schoolroom at the age of sixteen reasonably unspoiled and without undue vanity. Credit for this must go in large part to Miss Margaret Steele, the sober, fair-minded and determinedly moral governess recruited when Jane was ten years old.

The daughter of a scholarly but impoverished clergyman, Margaret Steele had been discreetly educated as a lady. She never married and when, on the death of her father, it became necessary to find a way of supplementing the meagre income bequeathed by her late parent the role of governess was one of the few acceptable occupations open to her. Her family was well known to Lady Andover and Lady Anson, and Lady Andover had no hesitation in offering Margaret Steele the position of governess to her daughter; not as a £40-a-year drudge at the mercy of the household but as a social equal who commanded the respect of the pupil’s family and whose opinions were heard.

Miss Steele took very seriously her duty to impart the behaviour and skills that Jane would require for her adult role in the highest ranks of society. These skills included a thorough training in music, needlework, the Bible, social deportment and other accomplishments not normally dealt with by the male tutor who had been engaged at Holkham for the young men of the family, who would later be shipped off to public school at the age of eleven or twelve to finish their education.

The governess had an apt pupil in Jane when Jane wished to attend. She quickly displayed, in common with her mother and aunts, a remarkable talent for painting. Margaret Steele – already irreverently called ‘Steely’ by her young charge – was not artistically gifted; however, Margaret’s elder sister Jane, who painted watercolours of a professional standard, gladly consented to tutor Jane Digby in this subject. Between them the two sisters had a great influence on Jane’s upbringing, and a deep affection developed between mentors and child which would last into the old age of all three. Steely’s nickname was apt: she was uncompromising in her steadfast obligation to duty and industry. She had a firm belief in Christianity and adhered strictly to the tenets of the Church of England, striving always for self-improvement. In the louche era of the Regency she was almost a portent of the Victorian ideal to come; in an earlier age she might have been a Puritan. However, Steely’s forbidding nature was offset by the presence of her gentler sister, who was soft and kind, and forgiving of the sins of others. Moreover, Steely had one failing of her own, a slightly guilty enjoyment of popular literature of a ‘non-improving’ variety such as the novels of Mrs Radcliffe, which the sisters used to read aloud to each other.

Jane’s lifelong delight in travel was fostered early. Her father rose quickly to the rank of rear-admiral and was often absent for long periods of duty with the fleet. In 1820, when it was necessary for him to visit Italy, Lady Andover accompanied him on the overland journey, and Jane and the Misses Steele went also, attended by Admiral Digby’s valet and Lady Andover’s French maid. They travelled in a convoy of carriages and luggage coaches, calling at Paris and Geneva. While they were in Italy thirteen-year-old Jane, obviously totally confident of her father’s love for her, engagingly requested an advance on her allowance. Her coquettish use of punctuation and heavy underscoring, sometimes teasing, sometimes firm, reflects their close relationship:

Rear Admiral Digby

Casa Brunavini

Florence, Italy

Florence, Thursday

Dearest Papa,

I write because I have a favour to ask which I am afraid you will think too great to grant; but as you at Geneva trusted me with [a] littler sum I am not ashamed, after you have heard from Steely my character, to ask a second time.

It is to … to … to advance me my pocket money, two pounds a week for 20 weeks counting from next Monday and I’ll tell you what for! If you approve I’ll do it but if not I’ll give it up!!!

Remember at Geneva after you advanced me 12 weeks, I never teased you for money until the time was expired. I promise to do the same here. Do not tell anyone but give me the answer. I will not ask for half a cracie until the time is expired. Think well of it and remember it is 20 ! ! ! weeks; I ask 40 pounds ! ! ! ! Not a farthing more or less. 40 pounds.

Goodbye and put the answer at the bottom of this [note]. I have long been trying to hoard the sum but I find that I want it directly and then I should not have it till we were gone. If you repulse me I will not grumble and if you grant it me ‘je vous remercie bien’. Pensez y and goodbye, mon bon petit père, I remain your very affectionate daughter.

Jane Elizabeth Digby

(#litres_trial_promo)

Unfortunately the surviving note lacks Admiral Digby’s response, and it is impossible to guess at the childhood desire that prompted such a request, or whether it was granted.

At the age of fifteen Jane was sent off to a Seminary for Young Ladies near Tunbridge Wells, Kent, for finishing. Here, in the traditions of English public school life, Jane fagged for an older girl, Caroline ‘Carry’ Boyle, during her first year.

(#litres_trial_promo) She missed her family but not unusually so, and to compensate she became a frequent correspondent, especially with her brothers, of whom she was very fond. Their notes to each other were partly written in the ‘secret’ code which she would use freely in her diary throughout her life.

(#litres_trial_promo)

There was a good deal to write about. Their grandfather Coke, only a year short of seventy, decided to remarry in February 1822. His bride, Lady Anne Keppel, was an eighteen-year-old girl, the daughter of a family friend, Lady Albemarle (who had died at Holkham in childbirth some years earlier), and god-daughter to Mr Coke. Furthermore, since Lady Anne’s father married a young niece of Mr Coke’s at the same time, there was a good deal of speculation that Lady Anne had married merely to escape from home.

Soon afterwards, Coke’s youngest daughter, Elizabeth (Eliza), who had reigned at Holkham as chatelaine while her father was a widower, married John Spencer-Stanhope and finally left the family home.

When Jane Digby left school at Christmas 1823, she was – as the French writer Edmond About wrote – ‘like all unmarried girls, a book bound in muslin and filled with blank white pages waiting to be written upon’.

(#litres_trial_promo) She was also a lively, self-confident young woman who adored her parents and was not above teasing her papa with humorous affection when she came upon a ‘quaint’ tract on his desk entitled ‘Hooks and Eyes to keep up Falling Breeches’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It had already been decided by ‘dearest Madre’ that Jane would make her début in the following February when the season started, rather than wait a further year. There is an unsubstantiated story that Jane was romantically attracted to a Holkham groom,

(#litres_trial_promo) and that an attempted elopement precipitated her early entry into society; however, according to her poems, Jane had thoughts and eyes for no one during these months but her handsome eldest cousin George Anson. It is doubtful that George, one of the most popular men about town, gave Jane more than a passing thought, for he was busy sowing his wild oats with married women; the hero-worship directed at him by his cousin was totally unrequited. Besides, there was a family precedent for early entry into society. Jane’s Aunt Anne was betrothed at fifteen, and made her début a year later.

Though no longer required in the role of governess, Steely remained as Jane’s duenna, to chaperon her during her forthcoming season when Lady Andover was engaged elsewhere. Miss Jane Steele continued to provide drawing lessons.

Had they been told that Jane would hardly be out of her teens before she would appear in one of the most sensational legal dramas of the nineteenth century, making it impossible for her ever again to live in England; that she would be so disgraced that her doting maternal grandfather Coke would cut her out of his life, and her uncle Lord Digby would cut her brother Edward (heir to the title Lord Digby) out of his will; that she would capture the hearts of foreign kings and princes, but would abandon them to live in a cave as the mistress of an Albanian bandit chieftain; that in middle age she would fall in love and marry an Arab sheikh young enough to be her son, and live out the remainder of her life as a desert princess, the Misses Steele could not possibly have believed it. Yet all those things, and much more, lay in the future for Jane Digby.

2 The Débutante 1824 (#ulink_59c600a8-8a40-52e2-9999-0c307efee697)

Unlike many of her contemporaries, Jane was not a stranger to London. Her parents owned a house on the corner of Harley Street ‘at the fashionable end’,

(#litres_trial_promo) so she would not have arrived wide-eyed at the bustle and noise noted by so many débutantes. However, as a girl who had not yet been brought out into society, the time she had previously spent there would have been very tame.

When not in the schoolroom Jane would spend her days shopping with her mother in the morning, if the weather permitted walking. In the afternoon she might walk in Hyde Park, chaperoned by Steely, and paint in watercolours or practise her music at other times. Jane and her brothers would have eaten informal meals with their parents, but for dinners and parties they would have been banished to the nursery – a far cry from Holkham, where the children often mingled with the adults. In town it was not possible for Jane to walk round to the stables and order her horse to be saddled for an invigorating gallop. It was necessary to appoint a given time for the horse to be brought round to the house, and it would be a solecism if a girl not yet out in society or even one in her first season went for a gallop in the park.

But all this changed when she took London by storm. The change to her life was an intoxicating experience. Now she breakfasted late with her parents and, while she might still shop with her mother in the mornings, it was for clothes and fashionable fripperies for her town wardrobe: new silk gloves or satin dancing slippers, an embroidered reticule for walking out, a domino for a masked rout, white ostrich feathers for her presentation, some ells of white sprigged muslin. Now she attended lessons in the cotillion and the waltz, given by a dancing master under Steely’s watchful eye. Now she rode her neat cover-hack in the park at the fashionable hour of 5 p.m., or rode with her mother in the chaise in Rotten Row, nodding to acquaintances, stopping for a chat with friends. Now the florist’s cart was never away from the door with small floral tributes from admirers.

The years of instruction by Steely at last bore fruit. Jane’s natural ear for languages enabled her not only to infiltrate foreign phrases into her conversation and correspondence – the outward sign of a well-rounded education – but also to converse in Italian, French and German with foreign visitors. All those music lessons that Jane had found a dreary bore were now justified, for after a dinner party she might be called upon to perform for her fellow guests. She was a good pianist, and played the guitar and lute; she also had a sweet singing voice. She acquired a wide repertoire of foreign love songs, which generally delighted her listeners. She was not slow to recognise when she captivated her hearers, and was feminine enough to enjoy doing so.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At sixteen, however, Jane was younger than the average débutante and had little experience of life. But she realised quite quickly that what was acceptable behaviour in the country was not so in London. A young lady might never venture abroad alone, on foot without a footman, or on horseback or in a carriage without a groom in attendance. She might, by 1824, have shopped with a girlfriend in Bond Street without raising eyebrows, just; but no lady would be seen in the St James’s area where the gentlemen’s clubs were situated. A young unmarried woman could never be alone with a gentleman unless he was closely related, and, while she might drive with a gentleman approved by her mama in an open carriage in the park, it must be a safe gig or perch phaeton and not the more dashing high-perch phaeton affected by members of the four-horse club, nor the newest Tilbury driven tandem. Either of the latter would have branded a girl as ‘fast’, even with a groom acting as stand-in for a chaperone. At a ball she must not on any account stand up to dance with the same man more than twice. The merest breath of criticism against a girl or her family was enough to prevent her obtaining a voucher from one of the Lady Patronesses of Almack’s.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Despite the high standards they set for patrons of Almack’s it would be fair to say that the private lives of most of the Patronesses would not stand close examination, for with one exception they all had famous affaires with highly ranked partners ranging from the Prince Regent himself to several Prime Ministers; however, they maintained a discreet appearance of respectability – a pivot, as it were, between the open licentiousness of the Regency and the rapidly approaching hypocrisy of Victorian morality.

Not to be seen at Almack’s branded one as ‘outside the haul ton’, so that, in effect, the Patronesses constituted a matriarchal oligarchy to whom everyone bowed, including the revered Duke of Wellington, who was turned away one evening for not wearing correct evening dress. Captain Gronow, the contemporary social observer, wrote: ‘One can hardly conceive the importance which was attached to getting admission to Almack’s, the seventh heaven of the fashionable world. Of the three hundred officers of the Foot-Guards, not more than half a dozen [Captain Gronow was one of those] were honoured by vouchers.’ Almack’s was a hotbed of gossip, rumour and scandal, and the country dances were dull. Matters improved somewhat after Princess Lieven and Lord Palmerston made the waltz respectable, though it was still regarded by many parents as ‘voluptuous, sensational … and an excuse for hugging and squeezing’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Alcoholic drinks were forbidden, and refreshments consisted of lemonade, tea and cakes, and bread and butter.

Why entrance to so prosy a venue should excite such passion, when the London season offered dozens of more exciting and enjoyable occupations every evening, can be explained by the fact that Almack’s was the most exigent marriage market in the Western world,

(#litres_trial_promo) and marriage was what the whole thing was about. It was desirable for a young man of decent background and respectable expectations to attract favourable connections through marriage, and if the wife had a good dowry so much the better. But it was essential for a young woman to contract an eligible match with a man who could provide all the social and financial advantages that she had been reared to take for granted. The lot of an unmarried woman past her youth in that milieu was unenviable – thrown, as it were, on to the charity and tolerance of her relatives. Jane Austen’s heroines exemplify, with a touching contemporary immediacy, the importance of a woman ‘taking’ duringdeher début.

Vast wardrobes of morning dresses, afternoon dresses, walking-out dresses, ballgowns, riding habits and gowns suitable for every conceivable occupation were necessary. But cloaks and gowns were only the start. Accessories, such as collections of hats ranging from the simple chipstraw to high-crowned velvet bonnets, were indispensable. Gloves of silk, lace, satin and kid for every occupation that might be fitted in between rising and retiring, from walking to riding to dining and dancing, were essential. Sandals, reticules, shawls, tippets, fans, chemises, camisoles and undergarments such as stays were obligatory. All of this, with luck, would form the basis of a girl’s trousseau in due course. Further expenditure included the cost of a good horse for riding in Hyde Park (a prime shopwindow in the marriage market) and the use of a carriage, since it was no use expecting a girl to travel everywhere by sedan chair. If the parents had no town-house of their own, and no relative with whom to stay, they must also bear the cost of hiring a house for the season as well as organising several smart dinner parties and soirées, and at least one ball. It was a huge investment, and this can only have served to heighten the pressure on the girl to fix the interest of a suitable man.

Jane made her début at a royal ‘Drawing Room’ in March 1824, when Lady Andover introduced her daughter to King George IV and the fashionable world. Henceforward Jane was an adult, free to attend adult parties and dances. With her background, connections and appearance, it was inevitable that she would be an immediate success. Her aunt, Eliza Spencer-Stanhope, wrote to the family that her sister, Lady Andover, was ‘graciously’ anticipating imminent conquests.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Vouchers for Almack’s were, of course, forthcoming for Lady Andover and her fledgeling, and Jane was subsequently to be seen at every ball, soirée, rout and dinner party of note. Young admirers wrote poems to her eyes, her shoulders, her guinea-golden curls; and she replied by telling ‘her wooers not to be “so absurd”’.

(#litres_trial_promo) No new entry truly made an impression unless a nickname attached itself to her; ‘the Dasher’, ‘the White Doe’ and ‘the Incomparable’ were typical. Jane became known as ‘Light of Day’.

The pencil and watercolour sketch made of Jane in 1824 shows her hair springing prettily from her high forehead, curling naturally into small ringlets around her face and coiled into a coronet. Large eyes fringed by thick dark lashes gaze serenely at the viewer and the sweet expression which might otherwise be serious is lifted by curved full lips. What the sketch does not convey is Jane’s colouring; oil portraits show that her hair was a rich tawny gold, her eyes dark violet-blue, and her fine clear skin a delicate pink. The sketch does not portray her figure (described by many diarists as ‘perfect … instinctive with vitality and an incomparable grace of movement)’,

(#litres_trial_promo) nor that when her pink lips parted her teeth were like ‘flawless pearls’.

(#litres_trial_promo) She had a roguish smile, a soft light voice and a pleasing modesty which gave way to lively animation once initial shyness had been overcome.

George IV was no longer the handsome Prince Regent of yesteryear but a tired and corpulent old man who walked with a stick. Nevertheless Jane must have enjoyed the thrill of the occasion. She wore the uniform white silk gown of simple cut, high-waisted with tiny puff sleeves, a sweeping train falling from her slim shoulders, long white gloves, and the de rigueur headdress of three white curled ostrich feathers. Small wonder that within days of her daughter’s presentation Lady Andover was so certain of a conquest that it was being noted in family correspondence. Small wonder that within a matter of weeks the youthful admirers who shoaled around Jane were scattered by a shark attracted into Jane’s pool of suitors.

Edward Law, Lord Ellenborough, was no stranger to Jane. She had met him at least once some four years earlier when he had sided with Thomas Coke in opposing the King’s wish to divorce. As a consequence Ellenborough had visited Holkham, though at that time Jane was a mere twelve-year-old occupant of the schoolroom. Now, creditably launched into society, although very young she was considered by many to be one of the catches of the season.

Ellenborough was thirty-four, a widower, childless, and by any standards eligible in the marriage market. He was rich and pleasant-looking, with a polished address, having been educated at Eton (where he was known as ‘Horrid Law’, and generally regarded as ‘prodigious clever’),

(#litres_trial_promo) and Cambridge. He had wanted a military career but his father, a former Lord Chief Justice in the famous post-Pitt ‘All the Talents’ coalition government, forbade it, so he entered the world of politics. By 1824 Edward, who succeeded to the title in 1819, had every anticipation of a Cabinet position. His late wife Octavia had been sister to Lord Castlereagh – Ellenborough’s political mentor – and The Times report of her funeral reflects their status:

At an early hour yesterday, the remains of Lady Ellenborough were removed from his Lordship’s house in Hertford Street, Mayfair. The cavalcade moved at half-past 6, and consisted of four mutes on horseback, six horsemen in black cloaks etc.

The hearse, containing the body enclosed in a coffin covered with superb crimson velvet, elegantly ornamented with silver gilt nails, coronets etc. and with a plate bearing the inscription; ‘Octavia, Lady Ellenborough, daughter of Robert Stewart, Marquis of Londonderry died the 5th of March 1819, aged 27’; was followed by five mourning coaches and four, with several carriages of the nobility etc.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Five years had passed since Lady Octavia’s untimely death. Meanwhile her brother had become the most hated politician of the day, and ended his life in 1822 by slitting his throat with a penknife. Probably England’s forty years of peace after Napoleon’s downfall owed much to Castlereagh’s period as Foreign Secretary,

(#litres_trial_promo) yet he was so despised that his coffin was greeted with shouts of exultation as he was borne to his grave in Westminster Abbey. Some of that odium still clung to Lord Ellenborough. Further, Ellenborough’s championship in 1820 of the former Queen Caroline’s cause, and a major speech in 1823 during a debate on the King’s Property Bill seeking to reduce George IV’s powers to dispose of Crown property, had permanently alienated his sovereign and made him persona non grata at court. Nevertheless Lord Ellenborough was a rising power in the land, despite whispered hints and rumours that he had some murky secrets in his private life and that he had been refused by several respectable young women.

Jane and Lord Ellenborough met in early April around the time of Jane’s seventeenth birthday, possibly at Almack’s. Less than eight weeks later Ellenborough sought permission from Admiral Digby to address Miss Digby (he always called her Janet) and a week later, on 4 June, Coke’s friend Lord Clare was writing to a mutual acquaintance, ‘I hear Ellenborough is going to be married to Lady Andover’s daughter.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

They were a handsome couple and each had much to offer a partner, but there was an obvious disparity in age and experience. Ellenborough was twice as old as Jane and a friend of her father, though at thirty-four he was hardly the raddled ancient roué that some Digby biographers have implied.

(#litres_trial_promo) The difference in years is anyway of questionable importance when within Jane’s own family there was ample evidence that April could successfully marry December. However, Ellenborough was an ambitious and mature politician who had little time to spare for social obligations unless they might further his work or career, and even less to cherish and instruct – let alone amuse – a child bride. Here was a man who, when obliged to entertain, would inevitably fill his table and his guest rooms with minor members of the royal family, ambassadors and senior politicians.

Jane was a young girl who only a few weeks earlier would have needed her governess’s permission even to ride her horse. This marriage would place her at a stroke in charge of an elevated domestic establishment, hostess to the country’s leaders and responsible for dozens of servants. Jane’s family connections were considerable, but Ellenborough had no need of them to further his career. Perhaps he fell in love with the enchanting girl, or at least was so charmed with her that he was willing to overlook her lack of experience. He desperately wanted an heir and her family had a record of healthy fecundity. It was said that he ‘courted her with the impatience and persistence of an adolescent boy’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

That Jane chose to marry Lord Ellenborough when, to judge from her family’s correspondence, she might have chosen a bridegroom nearer her own age is equally surprising. Previous biographers have speculated that Jane was compelled to marry Ellenborough by her parents, but there is no evidence to substantiate this. Jane could twist her father – whom she called ‘darling Babou’ – round the proverbial little finger, as surviving letters show, and it would have been out of character for either of her doting parents to coerce Jane into an unwanted marriage. Furthermore, Jane was so young that, even had she not found a match she liked in her first season, she could have returned again – as many girls did – for a second shot, still not having reached her eighteenth birthday. It seems far more likely that she was flattered by the attentions of an older, experienced man and that she romantically concluded that she was in love with him. This is borne out by poems that the couple sent each other, and by subsequent entries in Jane’s diaries. One of Lord Ellenborough’s poems tells of Jane’s love for him:

O fairest of the many fair

Who ruled, or seemed to rule my heart

The first I have enthroned there

Without a wish my bonds to part.

The thought that I am loved again

And loved by one I can adore,

That I have passed through years of pain

And found the bliss I knew before.

O ’twould have ta’en away my mind

But thy sweet smile a charm has given

And love’s wild ecstasy combined

With deepest gratitude to heaven.

(#litres_trial_promo)

His Lordship’s other poems spoke of ‘joy in the present day’ because of her and the bliss of knowing that ‘the next will be yet happier than this … Oh! this is youth and these the dreams of youth … And heaven itself is realised on earth.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

During their whirlwind courtship society found a synonym for Jane’s sobriquet ‘Light of Day. ‘Aurora’ was a name with which Jane could not have found fault in view of the fact that her father had once captained a ship of the same name, and it had a pretty sound. However, it was almost certainly intended to be less flattering to her suitor, Jane being cast in the role of Lord Byron’s sixteen-year-old heroine Aurora Raby, with Lord Ellenborough as the debauched, ageing, eponymous subject of the best-selling Don Juan:

there was indeed a certain fair and fairy one

Of the best class and better than her class,

Aurora Raby, a young star who shone

O’er life, too sweet an image for such glass.

A lovely being, scarcely formed or moulded,

A rose with all its sweetest leaves yet folded.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was not to be supposed because of the speed of the courtship that the marriage could be held with similar haste. During June the engaged couple enjoyed the last days of the season with its military reviews, balloon ascents, race meets and ridottos. As his fiancée Jane could ride publicly in Lord Ellenborough’s glossy phaeton, with his groom in attendance. She must be introduced to her prospective in-laws, Edward’s sister Elizabeth and his brothers, Charles and Henry. There were also the Londonderrys, his former in-laws, a valuable relationship he wished to maintain. When Lady Andover received a letter from Lady Londonderry congratulating her upon Jane’s betrothal and eulogising Lord Ellenborough,

(#litres_trial_promo) it must have been comforting to know that her cherished daughter was to marry such a paragon.

At the end of July, Edward visited Holkham, where he met the Cokes, Digbys, Ansons and Spencer-Stanhopes.

(#litres_trial_promo) It was not his first visit, but Jane must have derived immense pleasure from showing him some of the treasures of the great house, and riding with him in the parkland bordering the beaches. However, Edward and Mr Coke, having once been allies, had now moved apart politically; consequently his future visits to Holkham, and eventually Jane’s own, were few.

Shopping and fittings for the bridal clothes were time-consuming, and Jane must be taken over her future homes – an elegant pillared and porticoed town-house in Connaught Place, whose rear windows today overlook Marble Arch, and Elm Grove, Lord Ellenborough’s country house at Roehampton near Richmond.

(#litres_trial_promo) Yet somehow, during this time, Jane must have been instructed in her duties as chatelaine, for, although she would have had domestic instruction as she grew up, she would have had little reason to put such knowledge to practical use. Her mother wrote a treatise, which subsequently served as a model for other brides-to-be within the Coke family, upon the qualities requisite for ‘members of the household’, including that most valuable servant, the Lady’s maid:

Essentials for a Lady’s maid

She must not have a will of her own in anything, & always be good-humoured and approve of everything her mistress likes. She must not have an appetite … or care when or how she dines, how often disturbed, or even if she has no dinner at all. She had better not drink anything but water.

She must run the instant she is called whatever she is about. Morning, noon and night she must not mind going without sleep if her mistress requires her attendance. She must not require high wages nor expect profit from old clothes but be ready to turn and clean them … for her mistress, and be satisfied with two old gowns for herself. She must be a first-rate vermin catcher.

She must be clean and sweet … let her not venture to make a complaint or difficulty of any kind. If so, she had better go at once.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Few of Jane’s papers from this period survive and her journal is not among them. We know, however, that her parents were delighted with the match, and that Steely approved also. But there were some dissensions, notably among Ellenborough’s political opponents. One could not accuse the Duke of Wellington’s chère amie, Harriet Arbuthnot, of political bias, however, when she wrote that ‘Ellenborough having flirted and made himself ridiculous with all the girls in London now marries Miss Digby … she is very fair, very young and very pretty.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The diarist Thomas Creevey, who was a close friend of Jane’s aunt Lady Anson and knew Ellenborough well, wrote:

Lady Anson goes to town next week to be present at the wedding of her niece, the pretty ‘Aurora; Light of Day’ Miss Digby … who is going to be married to Lord Ellenborough. It was Miss Russell who refused Ld Ellenborough, as many others besides are said to have done. Lady Anson will have it that he was a very good husband to his first wife, but all my impressions are that he is a dammed fellow.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Lady Holland wrote to her son that Ellenborough ‘has at last succeeded in getting a young wife, a poor girl who has not seen anything of the world. He could only snap up such a one … she is granddaughter of Mr Coke who has another son!’

(#litres_trial_promo) Thus she broke the news that Jane’s grandfather had the felicity of a spare for his cherished heir. However, Lady Holland’s views on Lord Ellenborough were politically jaundiced; she disliked him intensely and openly held the opinion that he was impotent.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In August, Ellenborough noted in his diary that he had ‘dined with Janet at the Duke’s’. The Duke of Wellington’s London home was Apsley House, near Hyde Park. It was a huge formal dinner with many notables present, all much older than Jane. Ellenborough was clearly pleased at the manner in which Jane conducted herself in such august company.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The day designated for the marriage was 15 September 1824, some five months after their meeting in London. The venue was not, as might be supposed, the chapel at Holkham; with a new son only three weeks old, Jane’s step-grandmother could not accommodate a wedding party. Jane was married to Edward at her parents’ London house, as an entry in the register of the Parish of St Marylebone shows:

The Right Honourable Edward Lord Ellenborough, a Widower, and Jane Elizabeth Digby, Spinster, a minor, were married by Special Licence at 78 Harley Street by and with the consent of Henry Digby Esquire, Rear Admiral in His Majesty’s Navy, the natural and lawful father of the said minor, this fifteenth day of September.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was not unusual for a society marriage to be conducted in a private home. Slightly more unusual, perhaps, was that it was performed in a secular venue by a bishop, Edward’s uncle, the Bishop of Bath and Wells. The court pages reveal that the happy couple sped off to Brighton for the honeymoon where, as Jane recalled many years later, a wholly satisfactory wedding night followed.

(#litres_trial_promo)

3 Lady Ellenborough 1825–1827 (#ulink_fd88901e-2107-565c-9cf9-31e87d519d0b)

The honeymoon in Brighton lasted a mere three weeks and Lord Ellenborough was back at work in October. During the following period, though busy with affairs of great moment, he still found time to write poetry to his bride. The epithet ‘Juliet’ was only used in the first months of their marriage, probably as an allusion to Jane’s youth. Jane had a pet name for her husband – ‘Oussey’ – but in all surviving correspondence between the two she signed herself ‘Janet’, except in the following exchange:

Oh Juliet, if to have no fear

But that of deserving thee,

To know no peace when thou art near

No joy thou can’st not share with me

If still to feel a lover’s fire

And love thee more the more prospect,

To have on earth but one desire

Of making thee completely blest!

If this be passion, thou alone

Canst make my heart such passion know.

Love me but still, as thou hast done,

And I will ever love thee so.

Ellenborough, 12 November 1824

To which his bride of two months readily replied within twenty-four hours:

‘To love thee still as I have done’

Say, is it all thou ask of me?

Thou has it then, for thou alone

Reign in the soul that breathes for thee.

Edward, for thee alone I sigh

And feel a love unknown before

What bliss is mine when thou art nigh

Oh loved one still, I ask no more

As thou art now, oh ever be

To her whose fate in thine is bound

Whose greatest joy is loving thee

Whose bliss in thee alone is found.

And she will ever thee adore

From day to day with ardour new

Both now and to life’s latest hour

With passion, felt alas! … by few.

Juliet, 13 November 1824

Those words ‘whose greatest joy is loving thee’ hardly reinforce the image of a girl coerced into an unwanted marriage, nor charges that the marriage was a failure from the day of the wedding, and these facts are important in view of what was to follow. Visitors to Elm Grove found the couple happy together and living in terms of open affection.

(#litres_trial_promo) They rode out together most mornings when Edward was at Roehampton, often across Richmond Park.

(#litres_trial_promo) Joseph Jekyll, who visited the Ellenboroughs just before Christmas, wrote: ‘I dined and slept … at Roehampton to be presented by Lord Ellenborough to his bride. Very pretty, but quite a girl, twenty years younger than himself

(#litres_trial_promo) … The general subject was his lordship’s lamentation at being called away so frequently from his beautiful wife by debates and politics.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The poetry and literary love-making during Ellenborough’s absences continued for months, whenever Ellenborough was away from Jane, and some, such as the following extract from a poem written on New Year’s Day 1825 while he was staying at Boldrewood in Hampshire with Lord Lyndhurst, the Attorney-General and a close friend, is illuminating:

My bride! For thou art still a bride to me

And loved with all the passion of a soul

Which gave itself at once, nor would be free …

Yet I have had a roving eye, till now,

And gazed around on every lovely face

And still would, all enthralled to beauty, bow

But ne’er in fairest features could I trace

The sympathetic smile, and winning grace

Which beam aloft on thy illumined brow

And every thought of others is effaced

In dreams of bliss which heaven’s behests allow

So wedded truth alone, and love’s unbroken vow,

Ellenborough

Unless this poem came as a shock to her it seems that Jane was aware of Ellenborough’s reputation as a womaniser; he freely admits that he is still a potential rover were he not in love with his wife and her sympathetic smile and winning grace.

During her husband’s many absences Jane was initially content to get to know her new homes and learn the ordering of them. Steely was a visitor to Roehampton several times, as were Lady Andover and Lady Anson. Nor was Roehampton far from London, should Jane have felt the want of company. Once the 1825 season started, though, Jane removed to town and immediately her name featured regularly in the court page of the Morning Post as guest of socially prominent hostesses, often – but not always – accompanied by her husband, and also as the hostess herself of several formal dinners and a ball.

As the year wore on, however, hairline cracks began to appear in the fabric of the marriage. Lady Londonderry had earlier commended her former son-in-law for the five years of happiness he had given her late daughter, and Ellenborough’s biographers claim that the first Lady Ellenborough, Octavia, was the love of his life. Ellenborough is on record as saying that in his opinion whatever good he had done in his life was due to his first wife.

(#litres_trial_promo) Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that Jane, feeling rejected by her husband’s frequent absences and hurt by his apparent coolness, attributed the neglect not to his work but to his love for the dead Octavia.

In a poem to him, written about the time of the first anniversary of their wedding, answering Edward’s comment on her ‘lack of gaiety’, she asked his forgiveness for her jealous fears that Octavia ‘thy love of former years still reigns, while every thought and wish of mine is breathed for thee alone’. Beyond doubt she believed herself in love with her husband when she asked plaintively, ‘did her passion equal mine? Her joy the same when thou art near? And if not present did she pine?’

And here I am the fond, the young,

The blest in all that earth can give,

By men beloved, by lovers sung,

Yet silent, loveworn do I grieve.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Why did this marriage, which had begun so well, run into trouble so quickly? On the face of it Jane had everything most women of her world could have wished: love, wealth and social position. At least Edward’s poetry proclaimed love, and whatever his faults he was always generous. Jane had a ‘pin-money’ allowance that her female relatives regarded with envy,

(#litres_trial_promo) and on their marriage he presented her with a green leather box of family jewels. Even a year after their marriage he habitually returned from short absences with a costly gift of jewellery such as the emeralds for which Lady Ellenborough became envied. However, it becomes clear from her diary in later years that these gifts were not appreciated by Jane as much as would have been a display of warmth from her husband.

(#litres_trial_promo)

During the London season it was inconceivable that she would not attract the attention of admiring young men prepared to offer a solace her husband could not or would not give. Ellenborough might have smiled at the stir his wife created whenever she appeared in company, indeed basked in the thought that he possessed what other men so desired. Or he may have been so preoccupied and immersed in his work that he did not notice that the only time his bored young wife came to life was when she was the adored centrepiece of a crowd of young men.

Perhaps it is not surprising that Jane began to move away from her husband, in fantasy if not in deed. The next poem is almost certainly about George Anson, and was written after the visit of a horseman whom, at first sight from a distance, Jane mistook for her cousin. She recalled his winning look and had to ‘quell each rebel sigh’ at the thought of him. But then loyalty to Edward overtook her fantasy:

I may not think, I will not pause

One look behind my faith to shake.

Henceforth must buried be the past

Nor in my heart shall e’er awake

Its echo, for dear Edward’s sake.

(#litres_trial_promo)

So far as one can take this surviving written work as evidence of the pattern of their marriage, it is possible to conclude that Jane felt neglected by her husband and believed he no longer loved her. Given Ellenborough’s age and disposition, and Jane’s lively but romantically inclined personality, such a situation was always probable. Had she confided in her mother or Steely, she would undoubtedly have been advised to accept that Edward must be about his business. It would be wrong, however, not to produce another piece of the jigsaw at this stage. Edward had a mistress, and within six months of the marriage Jane apparently discovered a portrait of this woman in their home.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At this point, although the couple clearly had problems, the marriage survived a potential crisis. The Ellenboroughs spent some weeks in Paris during the autumn of 1825,

(#litres_trial_promo) and, at least to observers who would later testify to the fact, all seemed perfectly normal. In the following April, when seen by a member of the family at an early season ball, she was ‘on the arm of her Lord looking devastatingly handsome in black velvet and diamonds’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Two nights later she was noted by Mrs Arbuthnot at a Spanish ball held at the Opera House, where the company ‘Polonaised all around … Lady Ellenborough looked quite beautiful … it was altogether as magnificent a fete as I ever saw.’

(#litres_trial_promo) No event of any note, it seems, was held without the presence of this lovely young woman. And she was never without her crowd of male admirers. At the end of the season the couple spent several weeks in Brighton, staying at the Norfolk Hotel in a suite which they habitually engaged for regular visits to the seaside town.

The appearance of serenity was, however, a front. The eighteen-year-old Jane, still more child than woman, left more and more in her own company, was inexorably sucked into the glittering and sophisticated world of the European diplomatic set, to whom she had first been proudly introduced as Ellenborough’s fiancée. They were Edward’s friends and now they were hers too. She was intelligent enough to see that their rules on behaviour were not those of her own family, but it seemed to her that if these highly regarded people behaved in such a manner then she too could play by their rules. Her husband’s infidelity may have caused the new note of defiance in her conduct.

Jane’s activities were remarked by friends of the family, who were concerned that the young woman should be given a hint in order to correct any danger of being thought ‘fast’. Predictably, when her parents remonstrated with her, Jane defended herself vigorously, provoking an estrangement with her father which lasted some months.

(#litres_trial_promo) Steely spoke to her and, receiving no satisfactory response, took the matter up with Lady Anson. This conversation caused George Anson to be charged with keeping an eye on his young cousin, escorting Jane about town and guarding her reputation. It was an unfortunate commission. That summer, only two years after her marriage, Jane embarked upon a romantic liaison that had been waiting in the wings, so to speak, for several years.

George Anson was ten years older than Jane, yet they had known each other for ever. Perhaps he had not recognised the hero-worship of his pretty cousin that had begun when he returned as a handsome eighteen-year-old subaltern from the battlefield of Waterloo. Three years later, when Jane was still only twelve, Anson had just been elected to Parliament as the Member for South Staffordshire.

(#litres_trial_promo) He quickly became acknowledged by men of character as a likeable sprig and ‘a top sawyer’, despite a well-earned reputation for womanising.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘George Anson is to have all the married women of good character in London this year,’ wrote one to another good-naturedly. ‘And so he ought, for he is the best looking man I know.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

In fact, in his first years in town George was in one scrape after another, tipping a boatload of cronies into the Thames near Kingston, getting drunk, behaving outrageously with older women.

(#litres_trial_promo) He was believed to be the organiser of the famous quadrille at Almack’s in which both George and the lady he would later marry danced together all evening, to the irritation of many matrons:

I went two nights ago to a costume ball at Almack’s. It was all very brilliant and there was a quadrille that was beautiful. All the prettiest girls in London were in it … the men were in Regimentals and each wore a bouquet. The quadrille, however, gave great offence for they danced together all night and took the upper end of the room which was considered a great impertinence.

(#litres_trial_promo)

But Anson’s pranks were conducted with such innocent good humour and unselfconscious charm that he was instantly forgiven, particularly by women, who fell at his feet in droves. He was a cracking horseman and could drive a carriage ‘to an inch’; he was also one of the best shots in England.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Jane had been a pretty schoolgirl with a schoolgirl crush on him, but, as they both grew older, on two counts – her being a virgin and a member of his own family – she was strictly forbidden territory to George. He was used to tougher meat, his name being linked by both Creevey and Mrs Arbuthnot with the fastest women in town: in particular, the young Duchess of Rutland and Mrs Fox Lane, who, though the latter was considerably older than he, were both said to be his lovers.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In the summer of 1926 it was a different matter. Jane was a married woman and therefore a ‘safe’ target by the code of the day. She was among the most desirable women in London, her virginal sweetness having given way to a slim voluptuousness guaranteed to turn men’s heads. It was perfectly acceptable for George to escort his first cousin Jane to functions in the absence of her busy husband. George, as well as serving in several political posts, was now a colonel in the Guards, and Jane was delighted to have such a handsome and personable chaperon.

They were seen together often, at Almack’s, at the races, at a fireworks party. Almost certainly the affair began perfectly innocently with the touch of hands or a snatched kiss; but at some point it became something else. Two handsome young people, both with a healthy libido – ‘Oh it is heaven to love thee,’ she wrote, and ‘rapture to be near thee.’ If he only felt half the joy she experienced, then, ‘what ecstasy is thine!’ He swore undying love; she countered that he might – at some time in the future, when her beauty had gone – be seduced by others. Still, she claimed, she would be true to him, for ‘though all righteous heaven above, / Forbids this rebel heart to love, / To love is still its fate.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Gone now was all her resolution of quelling her ‘rebel sighs, for Edward’s sake’. She flung herself into the affair with passionate involvement. Such a remarkable couple could not escape attention; indeed, they were frequently mentioned in contemporary correspondence, and featured on the same guest lists of court pages, but at this stage there were no raised eyebrows and no gossip, because the pair were reasonably discreet. At Roehampton there was a side-door to the house from the garden which was little used and consequently kept locked. Jane gave the key to George so that he could come and go at night during Edward’s absences, without the servants seeing him.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At the same time, in a more public manner, and to the sustained disapproval not only of her parents but also of Steely (who visited Roehampton every two months or so as a friend of the family), Jane infiltrated deeper into the set of cynical, worldly men and women who, while considered by many to constitute the haul ton, the people of high fashion, were not at all suitable companions for a girl of nineteen. They included at least a brace of Almack’s Patronesses – Princess Esterhazy, the wife of the Austrian Ambassador, and Princess de Lieven, the haughty and imperious wife of the Russian Ambassador – as well as other leading members of the diplomatic set who were also the intimates of the King in the so-called ‘Cottage Clique’.

(#litres_trial_promo) All were regular dinner guests at Lord Ellenborough’s London house and at Roehampton, and their reciprocated hospitality was accepted by both Edward and Jane.

The Digbys’ distress at Jane’s behaviour was increased on the publication of a novel which, under the title Almack’s, could hardly fail to be a bestseller. It was a roman-à-clef in which the anonymous author provided only paper-thin guises for the real-life characters that populated its pages. The beautiful Lady Glenmore was widely identified as Lady Ellenborough. Jane was amused, not recognising the damage it would inflict upon her reputation. It was no comfort to her family that the book, in fact written by a member of the family (Eliza Spencer-Stanhope’s sister-in-law Marianne), presented as fiction several true incidents in Jane’s life.

During one of her visits to Roehampton, having been primed by Lady Andover, Steely delivered a stern lecture on the importance of a woman’s reputation. Jane appeared to listen, but several days later, in a letter to her former governess, she brushed Steely’s concerns aside on the grounds that the persons to whom she and her parents objected were Edward’s friends and must therefore be perfectly acceptable.

(#litres_trial_promo) By now Steely was so concerned about Jane that she overrode any personal sensibilities and went to see Lord Ellenborough. Her case was that Jane was mixing too freely with associates who, she insisted, were ‘gay and profligate’. Significantly she did not include George Anson in her list.

(#litres_trial_promo) Ellenborough clearly did not know whether to be angry or amused at such an approach from a woman who, though undeniably gently bred, was, when all was said and done, a former employee of his wife’s family. In the end his sense of humour got the better of him; he laughed and told Steely that he thought she was being ‘too scrupulous’, stating that he had ‘unlimited confidence in Lady Ellenborough’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It is surprising that Ellenborough did not connect Steely’s warnings with what was happening at home, for when he wrote to Jane in September from Stratfield Saye (the Duke of Wellington’s country seat in Hampshire) he spoke of her recent ‘coldness and indifference’ towards him. ‘But all is now forgotten,’ he continued.