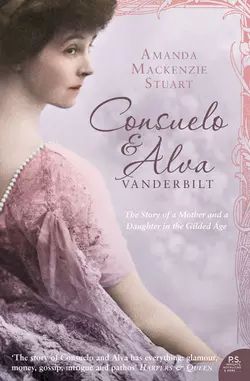

Consuelo and Alva Vanderbilt: The Story of a Mother and a Daughter in the ‘Gilded Age’

Amanda Mackenzie Stuart

The family trees contained within this ebook are best viewed on a tablet.A fabulously wealthy New York beauty marries a cold-hearted British aristocrat at the behest of her Machiavellian mother – then leaves him to become a prominent Suffragette.Consuelo Vanderbilt was one of the greatest heiresses of the late 19th-century, a glittering prize for suitors on both sides of the Atlantic. When she married, a crowd of over 2,000 onlookers gathered, and newspapers frenziedly reported every detail of the event, right down to the bridal underwear. Even by the standards of the day the glamorous, eighteen-year-old had made an outstanding match: she had ensnared the twenty-four-year-old Duke of Marlborough, the most eligible peer in Great Britain.Yet the bride’s swollen face, barely hidden under the veil, presaged the unhappiness that lay in the couple’s painful twelve-year future. It was not Consuelo, but her domineering mother who had forced the marriage through. This captivating biography tells of the lives of mother and daughter: the story of the fairytale wedding and its nightmarish aftermath, and an account of how both women went on to dedicate their lives to the dramatic fight for women’s rights, in the light of their own suffering.

CONSUELO

& ALVA

VANDERBILT

The Story of a Mother and Daughter in the Gilded Age

Amanda Mackenzie Stuart

To my daughters, Daisy and Marianna

Contents

Cover (#u486cd8ad-e0d7-5333-997b-aa4d8619afcd)

Title page (#ud023cb4e-5b42-5441-908e-de82477a311c)

PREFACE (#ulink_069f8433-4dc4-5c70-905f-0af6a4d396d8)

Prologue (#ulink_48534670-0da6-5418-998b-dd81e44c3f45)

PART ONE

1: The family of the bride (#ulink_fe5bc8e7-2170-5356-910f-970557254557)

2: Birth of an heiress (#ulink_8eb38c15-8fe1-50f7-a27e-ceb8f7285641)

3: Sunlight by proxy (#ulink_fa90060a-e520-5513-ad82-6b8f7cd64f97)

4: The wedding (#ulink_c740cc69-d02c-57ca-8448-4deaa77a65bc)

PART TWO

5: Becoming a duchess (#litres_trial_promo)

6: Success (#litres_trial_promo)

7: Difficulties (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE

8: Philanthropy, politics and power (#litres_trial_promo)

9: Old tricks (#litres_trial_promo)

10: Love, philanthropy and suffrage (#litres_trial_promo)

PART FOUR

11: A story re-told (#litres_trial_promo)

12: French lives (#litres_trial_promo)

13: Harvest on home ground (#litres_trial_promo)

Afterword (#litres_trial_promo)

NOTES (#litres_trial_promo)

BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

INDEX (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

PRAISE (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Select Family Tree of the Spencer-Churchills mentioned in the text

Select Family Tree of the Vanderbilts mentioned in the text

PREFACE (#ulink_c7f714f7-b610-52e7-abda-95f5b3d0618f)

This book began with a story. Some time ago, I took my eighteen-year-old daughter and a young Australian friend to visit Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, in order that the young Australian could have a glimpse of English ‘heritage’ before she went home. The guides at Blenheim Palace are free to talk about its history as they please, but there is one tale which engages visitors powerfully – the story of Consuelo Vanderbilt, an American heiress said to have been compelled by her socially ambitious mother to marry the 9th Duke of Marlborough in 1895, bringing a generous Vanderbilt dowry to an English palace sorely in need. Anyone wandering through the state rooms of Blenheim soon encounters two very different portraits of Consuelo. The first, by Carolus-Duran, was painted when she was seventeen against a classical English landscape and suggests an enigmatic but dynamic young woman, as yet little more than a girl. The second portrait, far more uneasy and much more famous, was painted eleven years later by John Singer Sargent. Here, Consuelo and the 9th Duke have been placed in their historical context beneath a bust of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, but at a distance from each other. Each inhabits a markedly private space linked only by their eldest son. Neither looks happy; but while the Duke gazes steadily outwards, Sargent has painted Consuelo glancing anxiously to one side with a striking air of melancholy.

It soon became apparent that our guide had little time for the 9th Duke. ‘This is Sunny,’ she said, gesturing at the Sargent portrait. ‘Sunny by name but most certainly not Sunny by nature.’ She glared severely at my daughter. ‘Consuelo was your age when she came to Blenheim. You’re probably still at school. But she got out in the end. Thank Heavens.’

Afterwards, the young Australian professed to be enthralled by English heritage, so we moved on to the nearby church of St Martin in Bladon, where Winston Churchill is buried in the churchyard with other members of the Spencer-Churchill family. Since his death, relatives buried alongside him have thoughtfully been redefined so that visitors can understand the relationship with Churchill at a glance. In one grave in the corner of the plot, however, an inscription reads: ‘Consuelo Vanderbilt wife of the ninth Duke.’ On the other side, her headstone is inscribed: ‘In loving memory of Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan – mother of the tenth Duke of Marlborough – born 2nd March 1877 – died 6th December 1964.’

This was startling. Consuelo had clearly remarried. So why had she come back? Surely no-one had compelled her to burial in a Bladon churchyard, even if she had been forced to Blenheim Palace in life? This puzzle was soon replaced by another. Limited research revealed that there were writers who rejected the allegation that Consuelo had been forced to marry the Duke and there were those, even in her lifetime, who asserted the story was a flat lie. This was followed by a further conundrum. It emerged that Consuelo’s mother, Alva, villainess-in-chief, eventually became a leader in the fight for women’s suffrage in America. How could anyone square even rudimentary feminism with ordering her daughter to marry a duke? One writer suggested she might have undergone a conversion to suffragism as an act of penance, but even on superficial acquaintance, Alva Belmont (as she later became) did not seem the penitential type.

It soon became clear that an account of what had happened and why would have to explore Alva’s life as well as Consuelo’s but there were further complications. The story of Consuelo’s first marriage had inspired others, notably Edith Wharton’s last (unfinished) novel, The Buccaneers. There were obstacles in the way of non-fiction, however. Consuelo and Alva left few private papers, and surviving sources were far from impartial. Both made attempts at autobiography. Consuelo’s memoir The Glitter and the Gold was published in 1952. Alva started her memoirs twice, once in 1917 and again after 1928, but neither version was completed. At the same time, the lives of both women were frequently the subject of comment in the press. Alva in particular encouraged this and intermittently attempted to influence and re-edit press narratives, including those relating to Consuelo. Mother and daughter spent a considerable part of their later lives thousands of miles apart, separated by the Atlantic, and both eventually preferred to be defined by events and activities beyond Consuelo’s life as Duchess of Marlborough. In spite of these difficulties, however, their lives prove more illuminating side-by-side than taken singly. They continued to influence each other; their interests and tastes eventually converged; and they found themselves defined and bound together for ever by the story of Consuelo’s first marriage.

Prologue (#ulink_9fea4264-af91-592d-8967-f2fa26299e0e)

IN NOVEMBER 1895, shortly before the New York wedding of Consuelo Vanderbilt to the 9th Duke of Marlborough, her cousin Gertrude raged at her journal about the unhappy lot of heiresses. ‘You don’t know what the position of an heiress is! You can’t imagine,’ she wrote, nib scratching paper with anger. ‘There is no one in all the world who loves her for herself. No one. She cannot do this, that and the other simply because she is known by sight and will be talked about … the world points at her and says “watch what she does, who she likes, who she sees, remember she is an heiress,” and those who seem to forget this fact are those who really remember it most vividly.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Had she been in a position to read her cousin’s journal, Miss Consuelo Vanderbilt would have agreed, for the world she knew was certainly watching and pointing. In the days leading up to 6 November 1895, preparations for her wedding dominated the front pages of New York’s popular newspapers, relegating to second, third and fourth place the advancing popularity of bloomers as cycling dress, New York State elections and a war of independence in Cuba. One newspaper, the New York World, led the field in examining the bride-to-be, providing its readers with a helpful list of her most important characteristics:

Age: Eighteen years Chin: Pointed, indicating vivacity Color of hair: Black Color of eyes: Dark brown Eyebrows: Delicately arched Nose: Rather slightly retroussé Weight: One hundred and sixteen and one half pounds Foot: Slender, with arched instep Size of shoe: Number three. AA last Length of foot: Eight and one half inches Length of hand: Six inches Waist measure: Twenty inches Marriage settlement: $10,000,000 Ultimate fortune: $25,000,000 (estimated).

(#litres_trial_promo)

As wedding preparations entered the final phase, a few enterprising passers-by near St Thomas Episcopalian Church on Fifth Avenue managed to peep in at the construction of the most spectacular wedding floral display ever assembled in a New York church: great flambeaux of pink and white roses on feathery palms at the end of pews; vaulting arches of asparagus fern, palm foliage and chrysanthemums; orchids suspended from the gallery; vines wound round the organ columns; floral gates constructed from small pink posies; and sweeping strands of lilies, ivy and holly swaggering from dome to floor, feats of festooning over 95-feet long. There was no shortage of other detail available for those with insufficient initiative – or interest – to seek it out for themselves. The press even provided lingering descriptions of the bridal underwear: ‘It is delightful to know that the clasps of Miss Vanderbilt’s stocking supporters are of gold, and that her corset-covers and chemises are embroidered with rosebuds in relief,’ said the society magazine Town Topics. ‘If the present methods of reporting the movements and details of the life and clothes of these young people are pursued until the day of the wedding, I look for some revelations that would startle even a Parisian café lounger.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

On the morning of 6 November, it was soon apparent that uninhibited staring was the order of the day. The wedding was at noon. At 72nd Street and Madison, where the bride was dressing at her mother’s house, the crowds started to gather before 9 a.m. and soon lined the entire route to St Thomas Church, twenty blocks away at 53rd Street and Fifth Avenue. At 72nd Street no-one was allowed within a hundred and fifty feet of Alva Vanderbilt’s new home, but all kinds of tactics were deployed by certain individuals determined to subvert the rules. By 10.30 a.m. the crowd had grown to around two thousand people, and windows in every house in the neighbourhood were crammed with spectators enjoying small private parties of their own. Curiosity was not confined to the common herd. Gertrude Vanderbilt’s outburst at the manner in which heiresses were watched was more than vindicated for lorgnettes were much in evidence and TheNew York Times noted that halfway down the block towards Park Avenue, women could be seen standing in bay windows peering out through opera glasses for glimpses of the bridal party.

(#litres_trial_promo)

As the morning wore on, crowd control outside St Thomas Church became increasingly difficult. Reporters fell back on military metaphor. Acting Inspector Cartwright was in overall command of forces; Captain Strauss was deployed with his platoon at the home of the bride; further detachments were stationed by the church preventing incursions on the left flank; and all faced a difficult and unpredictable enemy. ‘Picture to yourself a space 15-feet wide and 100-feet long,’ said the New York World, ‘tightly packed with young women, old women, pretty women, ugly women, fat women, thin women – all struggling and pushing and squeezing to break through police lines. Then imagine all those women quarrelling one with another, then struggling and pushing and squeezing and begging, imploring, threatening and coaxing the police to let them pass.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The most pressing problem for Inspector Cartwright was that some of the women came from good homes which put him in an invidious position and obliged him to give orders that clubs should not be used. ‘Had you seen those policemen pressed to desperation turn and push that throng back inch by inch, half crushing an arm here, poking a waist or a neck there, collecting three women in an armful and hurling them back, the crowd would have reminded you of nothing so much as an obstreperous herd of cattle,’ said one reporter.

(#litres_trial_promo)

There were compelling reasons for such intense curiosity. In an age of international marriages, of trade between American money and European titles, this was the grandest. The New York World went straight to the point: ‘Miss Consuelo Vanderbilt is one of the greatest heiresses in America. The Duke of Marlborough is probably the most eligible peer in Great Britain … From the standpoint of Fifth Avenue it will be the most desirable alliance ever made by an American heiress up to date.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The engagement was presented by others as an all-American tale that held out hope for everyone, even the poorest. ‘The world is actively engaged in making its fortune,’ said Frank Lewis Ford in an article in Munsey’s Magazine. ‘Though sometimes it calls the task by another name and says that it is earning its living, acquiring a competency, building up a business, or what not. And there stand the Vanderbilts, with living earned, competency acquired, business built up, fortune made.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

But to those in the know – and there were many people in the know thanks to the nature of the press in late-nineteenth-century New York – this was all too simple. The newspapers buzzed with rumours. Was it true that this wedding would break the heart of at least one eligible American bachelor? Was the English Duke simply marrying the eighteen-year-old bride for her money? And where were the Vanderbilts? Was it really possible that none of them had been invited? In America in the 1890s the lives of the very rich provided community entertainment supplanted later by cinema and television. This wedding alone was a soap opera with enough story lines to satisfy the most avid audience, laced with the faint but thrilling possibility of further drama at the church door. Might the eligible bachelor appear? Would rogue Vanderbilts attempt to force an entry? Could there be a misguided attempt to kidnap Consuelo to prevent her from marrying a blackguard, and stop her fortune from leaving the country? It was certainly worth waiting around to find out.

The wedding guests seemed just as determined to make the most of the occasion as the crowd. Some of them arrived as early as 10 a.m., a full two hours before the ceremony was due to start. This presented the embattled Inspector Cartwright with another headache because those in the crowd who had arrived early to obtain a good vantage point now refused to make way for the wedding guests, and had to be forced back inch by inch across the street. The guests, meanwhile, were required to dismount from their carriages and make their way to the church on foot. Here there were further difficulties, for the doors of the church were still tightly closed, creating a genteel but tense scrum as the ton barged each other out of the way. When St Thomas Church finally opened its doors, the gentlemen ushers, selected by Alva for their experience in seating guests at weddings, had to call for police reinforcements. The guests rushed past the sexton, whose task it was to match invitations to faces and expel interlopers. They ignored the efforts of the ushers to place them according to Mrs Vanderbilt’s list. Some of them (women again) climbed over the floral decorations, deposited themselves in the central aisle reserved for the guests of honour and were only removed to less prestigious seating by the gentlemen ushers with the utmost difficulty. Others stood on their pews to peer at fellow guests over the foliage – the floral display was widely held to be a great success but it undeniably obscured the sight lines.

Inside the church, official entertainment began with an organ recital from Dr George Warren, as sixty members of Walter Damrosch’s Symphony Orchestra moved into their desks. From 11 a.m., the orchestra played through a musical equivalent of the floral display in a programme at which even commercial classical radio stations might now baulk: the Prize Song from Wagner’s Die Meistersingers; the Bridal Chorus from Lohengrin; Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3; Tchaikovsky’s Andante Cantabile String Quartet; the Grand March from Wagner’s Tannhauser; Fugue in G Minor by Bach; and the Overture to A Mid-Summer Night’s Dream by Mendelssohn, all in the space of fifty-five minutes. Fifty members of the choir took their seats in the choir stalls, together with four distinguished New York soloists, and the guests of honour began to appear.

Mrs Astor arrived first with Mr and Mrs John Jacob. She was escorted to her seat by Reginald Ronald and looked particularly splendid in a costume of grey completed by a velvet coat and a black toque with white satin rosettes. Mrs William Jay, close friend of Mrs Vanderbilt, followed closely behind with Colonel Jay, wearing one of the most ‘effective’ costumes of the wedding – a heavy black silk skirt, cut very full and with a bodice of yellow and crimson satin. A peal of church bells announced the arrival of the mother-of-the-bride, Alva Vanderbilt, with the bridesmaids. Miss Duer, Miss Morton, Miss Winthrop, Miss Burden, Miss Jay, Miss Goelet and Miss Bronson were ‘all exceedingly pretty young women’ gushed the reporter in charge of bridesmaids for The New York Times.

(#litres_trial_promo) They wore gowns of ivory satin, with magnificent broad-brimmed velvet hats, topped with ostrich feathers, and around-the-throat bands of blue velvet with over-strings of pearls. All heads swivelled as Mrs Vanderbilt came up the aisle, accompanied by the bride’s brothers, Willie K. Jr and Harold. She was wearing a gown of pale blue satin edged with sable, a hat of lace and silver with a pale blue aigrette, and had ‘a decided look of satisfaction on her face’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Alva Vanderbilt’s smug expression was not to last. Her arrival signalled the imminent appearance of the bride, escorted by her father, William K. Vanderbilt. A row of fashionable bishops appeared from the vestry room and took their places in the chancel. The Duke of Marlborough, who had slipped into St Thomas Church unnoticed with his best man, Ivor Guest, took up his position and waited, incidentally giving the wedding guests a good opportunity to stare at him instead. One of them told a newspaper that ‘some of the guests partially rose in their seats to have a better view of the Lord of Blenheim. Some were asking where his relatives were and others answered that they were represented by the British Embassy.’

(#litres_trial_promo) This was true – the groom’s side was represented by the British ambassador, supported by two gentlemen from the embassy in Washington, Bax Ironsides and Lord Westmeath.

Along the New York streets and in St Thomas Church they waited. The ushers sauntered up to their stations, three on one side of the central aisle and three on the other – then sauntered back to the church porch again. Mr Damrosch, who had completed his concert programme, beat time with his baton in silence, his head turned round towards the church door. The Duke of Marlborough began to fidget nervously, and only regained some of his composure when he noted the English sang-froid of his best man. As the delay lengthened, the guests shuffled and whispered. Alva was observed looking uncharacteristically worried. And then decidedly strained. Five minutes passed … then ten … then twenty … and still the bride had not appeared.

PART ONE (#ulink_515f176c-eb94-53c7-9bc4-44cbe8e642ea)

1 The family of the bride (#ulink_a52017a1-83c0-59bb-8c80-a08915b218f9)

AS THE DELAY LENGTHENED and nervousness grew, self-appointed society experts in the crowd had time to debate one important question: had anyone seen the Vanderbilt family, whose apotheosis this was alleged to be? There could be no dispute that Vanderbilt gold was a powerful chemical element at work in St Thomas Church on 6 November 1895. It had given the bride her singular aura; it had drawn a duke from England; and without it, Alva would not now be waiting anxiously for her daughter to arrive. Scintillae of Vanderbilt gold dust brushed everything on the morning of Consuelo’s wedding, from the fronds of asparagus fern to the glinting lorgnettes in the crowd outside. It was remarkable, therefore, that apart from the father-of-the-bride, its chief purveyors should be so conspicuously absent; and even more striking that this scarcely mattered because of the force of character of the bride’s Vanderbilt great-grandfather, whose ancestral shade still hovered over the players in the morning’s drama as if he were alive.

Cornelius Vanderbilt, founder of the House of Vanderbilt, lingered in the collective memory partly because he laid down the basis of the family’s extraordinary wealth; and partly because of the robust manner in which he did it. He died in 1877, a few weeks before Consuelo was born, but he left a complex legacy and no examination of the lives of Alva and Consuelo is complete without first exploring it.

Fable attached itself to Cornelius Vanderbilt, known as ‘Commodore’ Vanderbilt, Head of the House of Vanderbilt, even in his lifetime. He generally did little to discourage this, but one misconception that irritated him was that the Vanderbilts were a ‘new’ family and he embarked on genealogical research to prove his point. However, he held matters up for several years by placing an advertisement in a Dutch newspaper in 1868 which read: ‘Where and who are the Dutch relations of the Vanderbilts?’, causing such offence that none of the Dutch relations could bring themselves to reply.

(#litres_trial_promo)

More tactful experts later traced the Vanderbilts’ roots back to one Jan Aertson from the Bild in Holland who arrived in America around 1650. A lowly member of the social hierarchy exported by the Dutch West India Company, Jan Aertson Van Der Bilt worked as an indentured servant to pay for his passage and then acquired a bowerie or small farm in Flatbush, Long Island. His descendants traded land from Algonquin Indians on Staten Island, starting a long association between the Vanderbilts and the Staten Island community of New Dorp. They also joined the Protestant Moravian sect, whose members fled from persecution in Europe in the early-eighteenth century and settled nearby. The Vanderbilt family mausoleum is to be found at the peaceful and beautiful Moravian cemetery at New Dorp on Staten Island to this day.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In a development that goes against the grain of immigration success stories, the Vanderbilt family arrived in America early enough to suffer a downturn in its fortunes in the mid-eighteenth century. Just at the point when the Staten Island farm became prosperous, it was repeatedly sub-divided by inheritance and by the time the Commodore was born in 1794, his father was scratching a subsistence living on a small plot, and ferrying vegetables to market on a periauger, a flat-bottomed sailing boat evolved from the Dutch canal scow. Historians of the family portray this Vanderbilt of pre-history as feckless and inclined to impractical schemes, but he compensated for his deficiencies by marrying a strong-minded, hard-working, frugal wife of English descent, Phebe Hands. Her family had also been ruined, by a disastrous investment in Continental bonds. They had nine children. The Commodore was their eldest son.

Circumstances thus conspired to provide the Commodore with what are now known to be many of the most common characteristics in the background of a great entrepreneur: a weak father and a ‘frontier mother’; a marked dislike of formal education (he hated school and spelt ‘according to common sense’); and a humble background.

(#litres_trial_promo) A humble background is almost mandatory in nineteenth-century American myth-making about the virtuous self-made man, but it was a characteristic the Commodore genuinely shared with others such as John Jacob Astor, Alexander T. Stewart and Jay Gould. After his death the Commodore was accused of being phrenologically challenged with a ‘bump of acquisitiveness’ in a ‘chronic state of inflammation all the time’, but he was not alone in finding that childhood poverty and near illiteracy ignited a very fierce flame.

(#litres_trial_promo) More unusually for a great entrepreneur, the Commodore was neither small nor puny. He developed enormous physical strength, accompanied by strong-boned good looks, a notorious set of flying fists and a streak of rabid competitiveness. Charismatic vigour, combined with a lurking potential for violence, made him a force to be reckoned with from an early age and even as a youth he developed a reputation for epic profanity and colourful aggression that never left him.

The Vanderbilt fortune was made in transportation. Its origins lay in the first regular Staten Island ferry service to Manhattan, started by the Commodore in a periauger, under sail, while he was still in his teens. From there his career reads like a successful case study in a textbook for business students. He ploughed back the profits from his first periauger ferry service until he owned a fleet. He expanded into other waters and bought coasting schooners. Then, when others had taken the risk out of steamship technology, he sold his sailing ships and embraced the age of steam, founding the Dispatch Line and acquiring the nickname ‘Commodore’ as he built it up.

The Dispatch Line ran safer and faster steamships than any of its competitors to Albany up the Hudson, and along the New England coast as far as Boston up Long Island Sound disembarking at Norwalk, New Haven, Connecticut and Providence. Between 1829 and 1835, the Commodore moved easily into the role of capitalist entrepreneur, profiting from the impulse to move and explore as waves of immigrants fanned out and built a new country. By 1845 he began to appear on ‘rich lists.’ The Wealth and Biography of the Wealthy Citizens of New York City, compiled by Moses Yale Beach that year estimated his fortune at $1.2 million and added ‘of an old Dutch root, Cornelius has evinced more energy and go-aheaditiveness in building and driving steamboats and other projects than ever one single Dutchman possessed’

(#litres_trial_promo). The size of the Commodore’s fortune is particularly remarkable when one considers that the word ‘millionaire’ was only coined by journalists in 1843 to describe the estate left by the first of them, the tobacconist Peter Lorillard. In 1845, the millionaire phenomenon was still so rare that the word was printed in italics and pronounced with rolling ‘rs’ in a flamboyant French accent.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was only in the last quarter of his life, between the mid-1860s and his death in 1877, that the Commodore moved into railroads – the industry with which the Vanderbilts are usually associated (this came after an adventure in Nicaragua where he forced a steamship up the Greytown River to open a trans-American Gold Rush passage in 1850, fomented a civil war and took his bank account to $11 million by 1853). It took much to convince the Commodore that railroads were the future: 30,000 miles of railroad track had to be laid by others before he accepted that the argument was won. Once convinced, he divested himself of his steamships and began buying up railroads converging on New York in a spectacular series of stock manipulations or ‘corners’ at which he proved extremely inventive and adept.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Commodore’s accounting methods may have been pre-industrial – he kept his accounts either in an old cigar box or in his head – but the enterprise he created made him a pioneer of industrial capitalism. He was also a master of timing. The American Civil War (1861–65) confirmed the absolute dominance of the railways at the heart of the growing US economy. On 20 May 1869, he secured the right to consolidate all his railroads into the New York Central, and recapitalised the stock at almost twice its previous market value. He was much abused for inventing the practice of issuing extra stock capitalised against future earnings, or ‘watering’ as it was known, but the practice has since become not only standard practice but a key instrument of modern finance.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The first version of Grand Central Terminal in New York, which opened in 1871, had serious design flaws, rather like the Commodore himself. Blithely ignoring the impact on the local community, trains ran down the middle of neighbouring streets and passengers wishing to change lines had to dodge moving locomotives and dive across the tracks in all weather conditions (in old age it amused the Commodore to play ‘chicken’ in front of oncoming trains). But this was the first American railroad terminal and it encapsulated an extraordinary achievement. ‘A powerful image in American letters,’ writes the historian Kurt Schlichting, ‘depicts a youth moving from a rural farm or small town to the big city, seeking fame or fortune … As the train arrives, the protagonist confronts the energy and chaos of the new urban society … Great railroad terminals like Grand Central provided the stage for this unfolding drama, as a rural, agrarian society urbanized.’

(#litres_trial_promo) In constructing the first version of the Grand Central Terminal (his statue still stands outside the 1913 version), the Commodore constructed a metaphor for both his own life and the industrialisation of America.

That, at any rate, was the business history, the journey from ferryman to railroad king which his first biographer, William Croffut, believed should be held up as an inspiring example to the young. This is not the whole truth, however. He may have been a great entrepreneur, but the Commodore had some disconcerting domestic habits. He is alleged to have consigned his wife, Sophia, and his epileptic son, Cornelius Jeremiah, to a lunatic asylum when they stood up to him; he was rumoured to be a womaniser, especially with the notorious Claflin sisters who were eventually prosecuted for obscenity (though not with him); and he dabbled in spiritualism for advance news from the spirit world on stock prices. There were many who objected to his meanness, for his habit of Dutch frugality was steadfastly extended to anything approaching a philanthropic gesture until very close to his death. ‘Go and surprise the whole country by doing something right,’ wrote Mark Twain in despair in 1869.

(#litres_trial_promo) New York society preferred to keep him at a distance too. There was, it was felt, altogether too much of the farmyard about him. He was even rumoured to have spat out tobacco plugs on Mrs Van Rensselaer’s carpet.

Alva later wrote that the Commodore was a charming old man. She came to know him in the last three years of his life, understood that he was a visionary and refused to be cowed by him which he always liked.

(#litres_trial_promo) He was certainly forthright, as a love letter he penned to the young woman who would become his second wife demonstrated: ‘I hope you will continue to improve for all time,’ he wrote after she had been ill. ‘Until you turn the scale when 125 pounds is on the opposite balance. This is weight enough for your beautiful figure.’

(#litres_trial_promo) It may be untrue that the Commodore spat out tobacco plugs, but he was not the only industrial tycoon unwilling to tone down a forceful style for genteel drawing rooms. Occasionally he was gripped by the urge to show off to snootier members of New York society but even this lacked conviction. In 1853 he commissioned the largest ocean-going yacht the world had ever seen, the North Star, and took his first wife and family to Europe. But though they were greeted by grand dukes, sculpted by Hiram Powers and painted by Joel Tanner Hart, he sold the yacht to the United Mail when he went home, never repeated the experiment and returned to what he enjoyed most, which was making money and doing down his competitors.

Unsurprisingly, the Commodore’s wealth inspired great jealousy as well as admiration. Some of the stories about his coarse behaviour came from his aforementioned competitors, and from embittered members of his own family contesting his will; he may also have played up to his image as a farmyard peasant when it suited him. Whatever the explanation, Frank Crowinshield could still write in 1941: ‘The most persistent myth concerning the family was that they were all, if not boors exactly, at any rate unused to the social amenities. The myth was so pervasive that one may still hear it from the lips of decrepit New Yorkers who, in discreet whispers, recite the risks their fathers ran in crossing the portals … Such people still speak as though their sires had risked calling upon Attila, or visiting, without benefit of axe or bludgeon, the dread caves of the anthropophagi.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The force of the Commodore’s personality was so great that it affected society’s perception of his children and grandchildren. For his own part, he left no-one in any doubt that his sons were a disappointment to him, and he was much exercised about the best way to hand on his great fortune until he felt he had solved the problem in the 1870s. There was naturally no question of giving any kind of financial control to his daughters; his favourite son died of malarial fever during the Civil War; and Cornelius Jeremiah, who not only suffered from epilepsy but also an addiction to gambling, was regarded as beyond redemption. This left Consuelo’s grandfather, William Henry Vanderbilt, who was treated with utter contempt well into middle-age, and was habitually addressed as ‘blatherskite’, not to mention ‘beetlehead’. William Henry – or ‘Billy’ as he was known to his family – made matters worse by kowtowing to his father at every turn. Even on the North Star cruise, he responded to the Commodore’s offer of $10,000 if he would give up smoking by refusing the money saying: ‘Your wish is sufficient,’ and flinging his cigar overboard. This tactic was so perfectly calibrated to irritate the Commodore that he slowly lit a cigar of his own and blew smoke in his son’s face.

(#litres_trial_promo)

William Henry was a far more careful, painstaking and methodical man than the Commodore, showing little of the latter’s startling entrepreneurial flair – one of many causes of the Commodore’s profound scorn. During his early career at a banking house, William Henry worked himself into a state of nervous collapse, attracting further contumely, and was promptly expelled with his wife Maria Kissam to work a small and difficult farm on Staten Island. (The Kissams were an old and distinguished family, and although Alva Vanderbilt later claimed to have propelled the Vanderbilts into society, this match could certainly have taken them into its outer circles if either party had been interested.)

On Staten Island, Maria Kissam Vanderbilt carried on the family tradition by producing a large family of her own – nine children in all. Three of her sons would later become Consuelo’s famous building uncles: Cornelius II of The Breakers, Newport; Frederick of the Hyde Park mansion, New York; and George, who created the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. The fourth – though not the youngest – was Consuelo’s father, William Kissam Vanderbilt, often known as ‘William K.’

In the family mythology, William Henry, the father of these sons, only finally won respect from the Commodore after many years with one of the double-crossing japes over a deal that nineteenth-century Vanderbilts seem to have enjoyed. It involved the definition of a scow-load of manure. William Henry offered to buy manure for his farm from his father’s stables at $4 a load. The Commodore then saw him pile several loads on to one scow and asked him how many he had bought. ‘How many?,’ William Henry is said to have replied; ‘One, of course! I never put but one load on a scow.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Finally impressed that his son was capable of getting the better of him, the Commodore, who was a shareholder in the near-bankrupt Staten Island Railroad, decided to turn it over to William Henry to see what he could make of it. Within two years the Blatherskite had put the little railroad on a secure financial footing and proved his value in the only vocabulary the Commodore truly understood by turning worthless stocks into $175 a share.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Commodore then moved William Henry and his growing family back from Staten Island to New York, made him vice-president of the newly acquired Harlem and Hudson Railroad, and put him in charge of the daily operation of the lines. Once again, William Henry responded magnificently to the challenge, finding economies and efficiencies wherever he looked, whereupon his father made him vice-president of the New York Central after 1869. The Commodore remained in overall strategic control of the enterprise until the day he died, but increasingly left the day-to-day management to William Henry. In coming to trust his eldest son’s managerial capabilities, the Commodore, always in the vanguard of entrepreneurial capitalism, grasped that the qualities needed to build a fortune were not the same as the qualities needed to maintain it. ‘Any fool can make a fortune,’ the Commodore is said to have told William Henry before he died. ‘It takes a man of brains to hold on to it after it is made.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The difficult relationship that existed for so many years between the Commodore and William Henry would have repercussions for Consuelo: her father, William Kissam Vanderbilt (later one of the world’s richest men) grew up in modest circumstances on Staten Island during the period when his parents were out of favour with the Commodore. Munsey’s Magazine found this reassuring, thankful that the humble circumstances principle would hold good for another generation or two: ‘The decline of ancestral vigour and the dissipation of inherited wealth, which sociologists claim is almost inevitable among the very rich, has doubtless been deferred for a very few generations, among the Vanderbilts, by the sturdy plainness in which William Henry had brought up his sons and daughters,’

(#litres_trial_promo) it said pompously. This may have been true, but it also meant that William K. would spend much of his adult life having as little to do with sturdy plainness as possible, an attitude to life with considerable implications for his own children.

William K. was also raised in a very different atmosphere from his father, who was a kind and mild-mannered man, an affectionate husband and not in the least given to domestic tyranny. A charming painting of the William Henry Vanderbilt family by Seymour Guy in 1873 suggests a large family at ease with itself, and even allowing for polite obituarists and nineteenth-century sentimentality, there appears to have been none of the contemptuous atmosphere that blighted the youth of the Commodore’s children. Maria Kissam came from a cultivated background and both she and her husband saw to it that their children were properly educated. Willie (as he was known) was taught by private tutors and his parents took the unusual step of sending him to Geneva in Switzerland for part of his education. According to architectural historians John Foreman and Robbe Pierce Stimson: ‘Few Americans of the time possessed the means, let alone the inclination, to send their sons abroad to school. Willie became a true sophisticate at an early age. He was fluent in French, and a connoisseur of European culture, art, and manners. The scandal-mongering tabloids of the era loved to portray the Vanderbilts as coarse parvenus. However, the truth in the case of Willie’s generation – and especially in the case of Willie himself – was precisely the opposite.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

William K. Vanderbilt grew into an outstandingly good-looking young man who later became famous for his charm, hospitality and agreeable manners. Consuelo adored him. ‘[He] found life a happy adventure …,’ she wrote. ‘His pleasure was to see people happy.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The problem for such a gregarious young Vanderbilt was that while his grandfather the Commodore was alive there was little possibility of making an entrée into New York society, or of enjoying a life of leisure. The Commodore’s reputation as a vulgarian put paid to contact with New York’s emerging social elite; and while his grandfather retained an iron grip on the family fortune, it was essential to behave as he wished. ‘What you’ve got isn’t worth anything unless you have got the power,’ was one of the Commodore’s favourite financial saws.

(#litres_trial_promo) Even in 1875, two years before he died, he continued to strike fear into the heart of his relations. He believed that extravagance was a weakness, a sign that one was not responsible enough to inherit a cent. ‘He’s a bad boy,’ he said of his son Cornelius Jeremiah. ‘Money slips through his fingers like water through a sieve.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

In 1868, William K., whom the Commodore liked, had no choice other than to join the family railroad enterprise alongside his brother Cornelius II and start learning the railroad business, some way down the hierarchy of the Hudson River Railroad. For a charming and sociable youth, this cannot always have been easy. For the time being, however, there was little alternative to assenting amiably to the Commodore’s assertion that only ‘“hard and disagreeable work” would keep his grandsons from becoming “spoilt”.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The person who would not only solve William K.’s problem but do much to change society’s perception of the Vanderbilts was Alva, nee Erskine Smith, later Mrs Oliver H. P. Belmont and the mother-of-the-bride. The reasons why she was drawn to this challenge lay deep in her own background, about which there remain many misconceptions. She has variously been described – in even scholarly works – as the daughter of the wealthiest couple in Savannah, and so poor that she helped her father keep a boarding house in New York after the American Civil War.

(#litres_trial_promo) Whereas Consuelo, her own daughter, thought that her mother was the daughter of a ruined plantation owner.

(#litres_trial_promo) Some of this was Alva’s fault for she often exaggerated to suit her purpose, particularly when it came to issues of status and power. Commodore Vanderbilt’s disdain for New York society was particularly unusual; for many others nineteenth-century America was a time of straightforward struggle for social advantage. Alva was one of them, and she was not alone in claiming aristocratic genealogy to assist her case.

On her father’s side, she maintained that her pedigree stretched back to Scotland, and the Earls of Stirling. She was named Alva after Lord Alva, a Stirling descendant, and she called her youngest son Harold Stirling Vanderbilt to underscore the connection. One of her Stirling forebears emigrated to Virginia, and married a Smith of Virginia. Her father, Murray Forbes Smith, was a descendant of this line. The antecedents of Alva’s mother, Phoebe Desha, were much less hazy. She – rather than Alva – was the daughter of a plantation owner, the distinguished and powerful General Robert Desha of Kentucky, who won his rank in the war of 1812, and was twice elected to the House of Representatives. Her uncle, Joseph Desha, was a governor of Kentucky. Thus far, Alva’s claims to a relationship with America’s southern landed aristocracy appear to have been valid, but in her parents’ generation they became diluted. Murray Forbes Smith had just finished training to be a lawyer in Virginia when he met Phoebe Desha. ‘His entire career, like all women’s but unlike most men’s was upset by this marriage,’

(#litres_trial_promo) Alva wrote later, for his powerful father-in-law persuaded him to abandon his fledgling legal practice and move to Mobile, Alabama to look after the family cotton interests. This made Murray Forbes Smith, in effect, a superior cotton sales agent working on behalf of the Kentucky Deshas.

While there may be some confusion about her background there is no doubt at all about the strength of Alva’s personality, which impressed itself on everyone who ever met her. ‘When convinced,’ said one witness ‘Not God nor the devil can frighten her off.’

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘When she speaks, prudent men go and get behind something and consider in which direction they can get away best,’

(#litres_trial_promo) said another. ‘Her combative nature rejoiced in conquests,’ wrote Consuelo. ‘A born dictator, she dominated events about her as thoroughly as she eventually dominated her husband and her children. If she admitted another point of view she never conceded it.’

(#litres_trial_promo) If anything, Consuelo, anxious not to appear over-critical of her mother, always downplayed Alva’s forcefulness. Alva, by contrast, seemed to take great pride in her own strength of character to the point of sounding puzzled by the strange impulse within her and writing in her (unpublished) autobiography: ‘There was a force in me that seemed to compel me to do what I wanted to do regardless of what might happen afterwards … I have known this condition often during my life.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Alva explained her dominant personality by saying that she had been born forceful, that she was the seventh child and – according to an old saying – the seventh child was always the strongest and the mainstay of the family. Elsewhere she attributed it to her upbringing, particularly her mother. ‘There is, I believe, no stronger influence on the development of character and personality than our early environment, and childhood memories,’

(#litres_trial_promo) she wrote. It is difficult to dispute this. Her domineering character was given free rein by her strong-minded mother in childhood, and family circumstances which involved a weakened father in her teenage years conspired to emancipate it entirely.

The Smiths moved to Mobile in boom years for the cotton trade, when Mobile was a great cotton port. In 1858, Hiram Fuller described Mobile as ‘a pleasant cotton city of some thirty thousand inhabitants, where the people live in cotton trade and ride in cotton carriages. They buy cotton, sell cotton, think cotton, eat cotton, and dream cotton. They marry cotton wives, and unto them are born cotton children.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Life for the Murray Forbes Smiths was not entirely happy, however. According to one account, Phoebe was determined to show the cotton wives how things were done by grand families such as the Deshas of Kentucky. Sadly, Mobile society was first indifferent and then irritated. Alva omits to mention in any account of her childhood that Phoebe’s attempt to conquer Mobile ended in abject failure, and would not have been pleased by a book which appeared some years later where her mother’s social efforts in Mobile were pilloried. ‘Some people ate Mrs Smith’s suppers; many did not. There was needless and ungracious comment, and one swift writer pasquinaded her social ambitions in a pamphlet for “private” circulation. Then the lady concluded that Mobile was … unripe for conquest,’

(#litres_trial_promo) commented Thomas De Leon in 1909.

Mobile must have been a difficult time for the Smiths in other ways. Alva was born on 17 January 1853, the seventh of nine children, of whom four died in infancy. Of the eight children born to the Smiths in Mobile, three are buried in Magnolia Cemetery – Alice, aged twenty months in 1847, one-year-old Eleanor in 1851, and thirteen-year-old Murray Forbes Smith Jr in 1857.

(#litres_trial_promo) In her memoirs (which she wrote after her conversion to the cause which would dominate her later life – women’s suffrage), Alva traced intense feelings of resentment towards men back to the death of this brother, Murray Forbes Jr. He died when she was four, and she grew up being made to feel that as far as her father was concerned, the death of his thirteen-year-old son and namesake was a far greater loss than her baby sisters. ‘He was always kind to us, always generous in his provision and care, but atmospherically he made his daughters feel that the family was best represented in the sons … I didn’t suffer with tearful sadness but with violent resentment.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

In spite of this, Alva remembered the house in Mobile with deep longing. The Smiths were comfortably off and their house stood at the corner of Conception and Government Streets, one of the grandest and most distinctive houses in Mobile with crenellations round the roof, and a Renaissance suggestion to the porches. Memory of the dream house of early childhood would haunt her all her life, influencing the design of the remarkable houses she created as an adult: ‘Always these houses, real and imaginary, reproduced certain features of the home in which I was born and where my early childhood was spent … It had large rooms, wide halls, high ceilings, with high casement windows opening upon the surrounding gardens … apart from the big house, also, was the bath house. The floor and bath were of marble, and marble steps led down into the bath which was cut out and below the level of the floor.’

(#litres_trial_promo) When Alva was six, her parents decided to leave Mobile and go to New York. Quite apart from his wife’s problems with Mobile society, Murray Smith sensed that success as a ‘commission merchant’ would be unsustainable if he stayed. His judgement (correct, as it turned out) was that the rapid spread of railroads would tip the balance from Mobile and the ports of the Gulf of Mexico in favour of New York. It was therefore the onward march of the American railroads that would ultimately bring the Smiths and Vanderbilts together.

The Smiths’ move to New York shortly before the Civil War initially seemed well judged. They avoided the depression in the South that came with the Civil War, and profited from a property boom in Mobile. Several characteristics of nineteenth-century southern life moved with them. Like almost every other well-to-do southern antebellum family, the Murray Smiths had slaves, given to Phoebe by her father in lieu of a marriage settlement. These slaves went with the Smiths to New York. Alva had her particular favourite, Monroe Crawford, whom she adored. ‘The reason Monroe Crawford and I got along without conflict for the most part was because I managed the situation, I wanted my own way and with Monroe I got it. I bossed him. It was a case of absolute control on my part,’

(#litres_trial_promo) she told Sara Bard Field, the writer and poet to whom she dictated her first set of memoirs in 1917. Though Alva never said so, this early exposure to a system of human relations based on slavery may explain as much about her as Murray Smith’s lack of interest in his daughters. She never entirely lost the habits of mind of a southern slave owner in relation to those she regarded as her inferiors: more profoundly such total control over another human being at such a young age can only have contributed to Alva’s later obsession with power and control, and her almost phobic fear of losing her grip on it.

There were other aspects of her childhood that set the Smith children apart from middle-class New York. First, they were unusually international in outlook, partly, no doubt, as a result of their southern parents. Prosperous southerners were a familiar sight in London even in the eighteenth century and Phoebe Smith loved travelling. She began taking her children abroad when they were very young. One expedition included a babe in arms, a little dog, two maids, and a southern mocking bird in precarious health in a large cage. They all crossed the Atlantic in a wooden paddle steamer on a voyage which took fourteen days, and travelled to England, France, Germany, Austria and Italy. While it would clearly have been easier to leave her children at home, Phoebe Smith liked to broaden their minds and teach them to observe. This international outlook also extended to fashion. ‘My mother, who loved the beautiful in dress as in all else, preferred the clothes made by European dressmakers, designed as they were by artists of an older civilisation, to those worn in her time by women in the United States. It was her custom, therefore, to order from Paris her own clothes, and later those of her children. Twice a year, from Olympe, a famous house of that day, would come a box containing clothes sufficient for our needs for the next six months.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Alva would pass on this feeling for French style and couture to Consuelo, but in childhood she did not appreciate being a fashion pioneer. Parisian outfits were a major provocation to sniggering little New York boys, whom she claims to have pitched into the gutter.

One striking feature of Alva’s account of her nineteenth-century upbringing in New York is the extent to which she presents herself as an aggressive, violent child. It was impossible to find a nurse to manage her. When she wanted to leave the nursery for a room of her own she smashed it up; and she particularly enjoyed thumping boy playmates when displeased. Any boy who teased her soon learnt better. ‘I can almost feel my childish hot blood rise as it did then in rebellion at some such taunting remarks as “You can’t run”; “You can’t climb trees”; “You can’t fight. You are only a girl,”’ she once wrote in a letter to a friend.

(#litres_trial_promo) Even at thirteen, passers-by had to pull her apart from a male tormentor in a fight so fierce that Alva boasted it was reported in the local newspaper. No-one has ever succeeded in tracing this report, but it is telling that it was a story Alva liked to recount about herself. ‘I caught him and threw him to the ground. I choked him and banged his head upon the ground. I stomped on him screaming: “I’ll show you what girls can do,”’ she told Sara Bard Field.

(#litres_trial_promo) It comes as no surprise that Alva had few girl playmates. She greatly preferred playing with the opposite sex, for she found boys’ lives more interesting. ‘I wanted activity and I could not find enough of it in the circumscribed and limited life of a girl. So I played with boys and I met them on their own ground. I asked for no compromise or advantage. I gave blow for blow.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

It is perhaps surprising that although she detested the life conventionally lived by nineteenth-century American girls, Alva liked playing with dolls and designing imaginary houses – two activities that she regarded as closely connected. She told Sara Bard Field that she was unable to sleep if her sisters left their dolls sitting up with their clothes on: ‘I loved dolls … I took them very seriously. I put into their china or sawdust bodies all my own feelings. They could be hot or cold. They could be weary, sleepy and hungry. Their treatment had to vary accordingly to these supposed conditions.’

(#litres_trial_promo) She saw this as a childish manifestation of maternal instinct which she thought men had downgraded. She saw no contradiction between her love of dolls and her rebellion against the constricted life of a girl, claiming: ‘It is because I must have felt then in an inarticulate way and feel now with a passionate conviction that the very fact of her maternity which men have used to lower woman’s status, raises her to superior position. Thus my love for the doll children and my rebellion against the superimposed restrictions of a girl’s life were bound up together’

(#litres_trial_promo) – an insight which would have an impact on Consuelo later.

Phoebe Smith was ahead of her time in the amount of freedom she granted her headstrong daughter, allowing Alva to ride out alone all day when they holidayed in Newport. She had no hesitation, however, in whipping Alva when the boundary was finally crossed – when, for example, she took a horse from the stable and rode bareback in the garden (Alva maintained that the pleasure was worth the whipping, and her streak of physical daring was noted by others throughout her life). Alva expressed it to Sara Bard Field thus: ‘My Mother found me the most difficult of all her children to train. The combination of rebellion and daring were difficult for her to meet. And in those days there was no Montissori [sic] methods and books on child psychology by which parents directed their training of children. The rod was the all-sufficient guide and to this my Mother resorted. There is a record in our family of my receiving a whipping every single day one year … but the end I desired was always strong enough to overcome the fear of the whipping … I was an impossible child.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Moving north before the start of Civil War, the Smiths appear to have made a smooth entrée into New York society. New York’s elite at this period has often been seen in terms of a dichotomy between the old introverted ‘Knickerbockcracy’ – descendants of the original Dutch settlers, the Knickerbockers – on the one hand, and extrovert new money on the other. However, New York society was always more permeable than this suggests, and making one’s mark on society was largely a question of becoming part of the right networks and (unlike the Commodore) demonstrating that one understood society’s rules and wished to opt in. Genteel in values, tone and style, the Smiths fitted quite easily into New York’s socially mobile elite before the Civil War, and there is every reason to suppose that without this unfortunate interruption, they would have soon felt well established. After a brief spell in a house at 209 Fifth Avenue, the family moved to a fine house at 40 Fifth Avenue, built for an affluent merchant in the 1850s by the well-known architect Calvert Vaux. New York City tax assessments of the house bear out Alva’s assertion that the family was well-to-do at the time of the move north, for records put its value at between $25,000 and $39,000, making it one of the more valuable houses in the city.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Nonetheless, some of Alva’s assertions about the social position of the Smiths in New York during this pre-war period are simply wrong – saying much about Phoebe’s own social anxieties since she was probably the source of the errors. Alva maintains, for example, that her mother was on the receiving line for the Prince of Wales at a famous ball held in his honour in New York in 1860. If true, this would have put Phoebe Smith at the pinnacle of society, but the ball took place on 12 October, seven days before Phoebe gave birth to her second daughter, Julia, in Mobile, Alabama.

(#litres_trial_promo) Phoebe would not have stepped out of doors, let alone travelled to New York. Similarly, Alva suggests that the Smiths’ entrance into New York circles came through the department store owner Alexander T. Stewart, but Stewart had an uneasy relationship with New York’s elite because he was a shopkeeper, and was suspected of vulgarity. The Smiths did not, as she claimed, have a box at the Academy of Music, though they may well have attended performances there; neither did they have a pew at Grace Church (one clear marker of membership of New York’s inner circle), though they belonged to another fashionable Episcopalian church, the Church of the Ascension.

On the other hand, Murray Forbes was elected to the Union Club in New York in 1861. This was a significant social success since one of the most important developments in the emerging exclusivity of New York society was the expansion of gentlemen’s clubs. Like gentlemen’s clubs in London, New York clubs were, to quote the historian Eric Homberger, ‘rooted in an ethos of exclusion’.

(#litres_trial_promo) The Union Club was the first of the gentlemen’s clubs from which many others emerged as a result of splits and disagreements. Membership was limited to a thousand members and lasted for life unless one chose to resign. By 1887 an observer noted that ‘membership in the Union implies social recognition and the highest respectability’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Founded purely for social (as opposed to political or sporting) purposes, the Union Club’s early membership tended to favour merchants over ‘gentlemen of leisure’, but even here, Murray Smith was several steps ahead of the Vanderbilts. The Commodore had become a member in 1844, resigned and then rejoined only in 1863. William Henry Vanderbilt would not become a member until 1868, and William K. Vanderbilt was only elected to the club after his marriage to Alva and the death of his grandfather in 1877.

The outbreak of the Civil War, however, brought real difficulties for the Smiths. They were slave owners; Murray Forbes Smith did not believe that slaveholding was wrong, and took the view that emancipation was only possible if it happened gradually. As hostilities began, tension with northern neighbours escalated. One of the first places this manifested itself was in the Union Club itself. According to the club’s historian: ‘feeling rose high against the South in New York … Many Southerners, including Benjamin [the Confederate Secretary of State] and Slidell [the Confederate Commissioner to France] resigned, and more were dropped for non-payment of dues.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Such clashes were not surprising in view of the fact that the Union Club’s membership also included General Ulysses S. Grant, General William Sherman and General Philip Sheridan, as well as twenty-four Confederate major generals. The abolitionist views of the rector at the Smith’s church, the Church of the Ascension, caused such offence to the southern members of the congregation that they all withdrew. Mounting tension affected the children directly too – this was a time when Jennie Jerome, later Lady Randolph Churchill, remembered pinching little southerners with impunity at dancing class.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The turning point, according to Alva, was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln just after the end of the war on 15 April 1865. The Smiths felt obliged to sign up to the general mood of mourning, putting black bows of bombazine in their windows to avoid attack. By now, Alva recalled, ‘feeling against southerners had risen from unfriendliness and suspicion to active antagonism and enmity,’

(#litres_trial_promo) scarcely surprising considering that the city had lost over 15,000 men to the war and, in a last desperate throw of the dice, Confederates attacked New York itself by setting fire to ten hotels in November 1864.

Bows in the window, it turned out, were not enough to prevent unpleasantness. After the President’s funeral, life became so difficult for the family that Murray Forbes Smith decided they should not remain in New York and sold their fine house on Fifth Avenue to a Mr McCormick of Chicago, inventor of the reaping machine. Social and business networks in New York once plaited closely together were torn apart by wartime antipathies. The cotton trade was disrupted by the war, and so was the transport system from south to north.

From 1866, Murray Forbes Smith based his business activities in Liverpool, the main English port for cotton from the southern states. That summer, when Alva was thirteen, the Smith family briefly took a villa on Bellevue Avenue in the resort of Newport, Rhode Island, where they probably met the Yznaga family for the first time. Mr Yznaga was Cuban and owned a cotton plantation in Louisiana that had been worked by over three hundred slaves before the Civil War. Mrs Ellen Yznaga was of New England stock but was thought ‘fast’ by some. These attributes were enough to disbar them from certain aristocratic New York households after the Civil War. At one point the Yznagas owned a house in New York on 37th Street, but in the post-war years their fortunes fluctuated so dramatically that they ended up living in Orange, New Jersey and the Westminster Hotel in New York. In the summer of 1866, however, they were still in a position to spend the summer in Newport. This was almost certainly the time of Alva’s fight as a thirteen-year-old with a male tormentor, for her opponent was a Yznaga houseguest. She spent much of that summer fearlessly rolling down a hill that ended in a cliff face in the company of Fernando Yznaga, her future brother-in-law; and started a long and important friendship with Consuelo Yznaga, who was about three years her junior, and almost as high-spirited.

Soon after this, and quite possibly speeded on their way by some of Newport’s matrons, Phoebe took her daughters to Paris, rented an apartment on the Champs Elysées and set up home. Although the Smiths kept smaller houses in New York throughout the period, they were based in Paris for much of the time between 1866 and 1869. Like other southern families who appeared in Paris during and after the Civil War, they were able to live well in reduced and uncertain circumstances. Apparently affluent, they were welcomed by the imperial court of Napoleon III and the Empress Eugenie, at a time when the Second Empire was at its most brilliant and glamorous. Precise gradations of wealth and social distinction of New York meant little to society circles in Paris. The Smiths were able to mix on easy terms with French aristocracy, equally untroubled as to how or when the latter had acquired their noble titles, some more recent than others. Lilian Forbes of the Forbes family, who had been a neighbour of the Smiths in New York, married the Duc de Pralin. Prince Achille Murat, distantly related to the Smiths by marriage, called at the house. The Marquis Chasseloup Loubat, who was Napoleon III’s Ministre de la Marine, and married to an American, Louise Pelier, was particularly cordial in his invitations, inviting Phoebe and Alva’s eldest sister, Armide, to select dances, and inviting the children to the Ministere de la Marine to watch processions. In Paris, Phoebe arranged a debut for Armide (who would never marry) and launched her into French society.

The impact on Alva of the move to Paris would have many consequences in the decades to follow: for American architecture, for the Vanderbilts and for Consuelo. Now in her early teens, she fell passionately in love with France, and above all with its history, art and architecture. In New York she had been just as resistant as the Commodore to attempts at formal education (‘I could not learn from impersonal pages. I wanted the contact of mind with mind. I liked the friction of thought it engendered,’

(#litres_trial_promo) she remembered later.) Now she responded to the clarity, rigour and competitiveness of French schooling which appealed to both ambition and pride; she particularly liked the French approach to learning history which she thought made sense. At one point she even demanded to go to a boarding school run by one Mademoiselle Coulon. She enjoyed this too, though she continued to prove a most difficult girl to handle and only stayed for about a year.

Much of Alva’s French education, therefore, was a freelance affair in the hands of French and German governesses, with trips to places that appealed to Miss Alva Smith. Thanks to the ever-expanding French railway system, there were frequent visits to the great Renaissance chateaux on the Loire, and to Versailles. It is understandable, given her dominant personality and her love of history, that Alva would be drawn to the magnificent architecture of both the French Renaissance and of the Bourbons. It is easy to imagine her walking in awe through the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, or believing that the apartments of Madame de Pompadour really belonged to her, or sketching the Petit Trianon for the umpteenth time – doubtless followed by a breathless governess much relieved to have found a way of passing the time in such an acceptable manner.

At the height of the Second Empire there was much to grip the imagination of such a child: French history was invested with a magical quality of particular intensity. As Alistair Horne writes: ‘The haut monde escaping from the bourgeois virtuousness of Louis-Philippe’s regime had sought consciously to recapture the paradise of Louis XV. In the Forest of Fontainebleau courtesans went hunting with their lovers attired in the plumed hats and lace of the eighteenth century.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The retrospective mood was set by Louis-Napoleon himself who loved to appear as a masked Venetian noble (masked balls being a particular feature of the Second Empire’s illusory and fantastic world).

There were times, indeed, when the imperial court reminded observers of an endless Venetian carnival, with every ball outdoing the one before in dazzling display. One of the most extraordinary balls was given in 1866 by the Smiths’ friend, the Ministre de la Marine, where the guests formed tableaux vivants of the four continents and ‘a procession of four crocodiles and ten ravishing Oriental handmaidens covered in jewels’ entered in front a chariot in which one English guest noticed the Princess Korsakow was seated en sauvage. Africa was represented by Mademoiselle de Sevres, ‘mounted on a camel fresh from the deserts of the Jardin des Plantes, and accompanied by attendants in enormous black woolly wigs’; finally came America – ‘a lovely blonde, reclined in a hammock swung between banana trees, each carried by Negroes and escorted by Red Indians and their squaws’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Three thousand guests came to this ball which cost about 4 million francs. Although there were balls and assemblies a-plenty in New York before the Civil War – indeed they were deeply embedded in the structure of society life – there was certainly nothing that came close to such a ball in terms of fantasy or expense until, that is, Alva threw one herself in 1883.

As a young lady protected from the seamier side of Second Empire life, Alva could see only enchantment in the Paris of Napoleon III. It seemed to embrace a great international vista, a future of scientific wonders as well as a magical past, encapsulated in the Great Exhibition on the Champs de Mars in 1867. The Great Exhibition was an extraordinary, opulent, dreamlike, awe-inspiring spectacle: As dusk fell, the Goncourts exclaimed that ‘the kiosks, the minarets, the domes, the beacons made the darkness retreat into the transparency and indolence of nights of Asia’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Alva particularly remembered the astonishing exhibits of Thomas Edison, and looking on in wonder from the windows of their apartment on the Champs Elysées at the great reviews held in honour of visiting kings and emperors by Napoleon III. ‘The people seemed to worship their Imperial family,’

(#litres_trial_promo) she later said wistfully. Alva may have spent her year at Mademoiselle Coulon’s school in 1868–9, while her parents moved back and forth between houses in New York and Paris.

(#litres_trial_promo) In 1869, however, Murray Smith decided that the whole family must return permanently to the United States. Sixteen-year-old Alva was utterly distraught. ‘I was broken hearted that I must leave France. I was in sympathy with everything there. This musical language had become mine. I loved its culture, art, people, customs. Child that I was, America struck me in contrast to France, as crude and raw.’ France, unlike America, was a ‘finished product’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The New York to which the Smiths returned in 1869, was a very different city to the one before they left for France in 1866. Capital markets were already centralising in New York by the end of the Civil War in 1865. Commodore Vanderbilt’s consolidation of his railroads in 1869 was a harbinger of things to come. The drive to expand the economy for military purposes had created a national market for the first time and war precipitated an almost limitless demand for goods that only increased with peace. This was the beginning of what Mark Twain termed ‘The Gilded Age’, the period spanning the final third of the nineteenth century that ended when Theodore Roosevelt became President in 1901, determined to control its worst excesses.

Twain’s novel The Gilded Age satirised what he described as ‘the inflamed desire for sudden wealth’,

(#litres_trial_promo) and came to define the period of about thirty-five years of economic boom centred on New York, characterised by rapid industrialisation, urbanisation and technological invention, harsh social inequity, grandiloquent, competitive opulence and by a relentless drive towards economic monopoly and big business. A new phenomenon, the industrial corporation, emerged quite suddenly, driven forward by intensely competitive individuals with energy as great as the Commodore’s, whose corporate power was unrestrained and who were assisted by corrupt politicians and a regime of virtually non-existent taxation – inheritance tax expired in 1870, income tax was abolished in 1872 and tax on corporate profits did not exist. Labour costs were low, and workers had yet to organise themselves efficiently against exploitation. The potential for vast personal fortunes suddenly became limitless. Those who did well out of the war continued to fare very well after it was over. Wealthy men became richer; others suddenly acquired fortunes overnight.

The fact that Murray Forbes Smith had sold his Fifth Avenue house to new money from Chicago was significant. The newly rich flocked to New York, often accompanied by wives determined to partake of the delights of New York society. Before long, ‘old’ New York felt itself besieged by outsiders, an impression born out by the demographics of the period and a range of expressions for the new arrivals: ‘social climber, men of new money, arriviste, bouncer, (as in the Yiddish Luftmensch, air man, someone who has arrived apparently from nowhere). The parvenus, objects of fierce social mockery, were assumed to be rich, crude, half-educated, and were seen as embodying the raw hunger for social distinction.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Smiths had put down a marker in New York society between 1861 and 1865, but after absenting themselves for nearly four years, they came back to the city to find themselves at a remove from its inner circle. Worse, they discovered that there were far more people knocking on high society’s door demanding admission and that the financial cost of re-entry had gone up sharply. In the early 1870s, according to Eric Homberger, ‘New York was literally swirling with cash. Prices rocketed, but even inflated costs seem to have no effect upon the ton … The holdings of the New York banks had risen from $80 million in the early 1860s to $225 million in 1865. When the Open Board of Stock Brokers merged in 1869 with the New York Stock & Exchange Board, forming the New York Stock Exchange, membership increased from 533 to 1,060. There were many more millionaires in the city than there had ever been before.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

In his memoir SocietyAsI Have Found It, the southern gentleman Ward McAllister made the same point: ‘New York’s ideas as to values, when fortune was named, leaped boldly up to ten millions, fifty millions, one hundred millions, and the necessities and luxuries followed suit. One was no longer content with a dinner of a dozen or more, to be served by a couple of servants. Fashion demanded that you be received in the hall of the house in which you were to dine, by from five to six servants, who, with the butler, were to serve the repast.’

(#litres_trial_promo) In an era of conspicuous consumption, this had an immediate impact on modish womenfolk. The newspapers began to notice, for example, that the cost of dressing fashionably was reaching breathtaking new levels. ‘Ladies now sweep along Broadway with dresses which cost hundreds of dollars,’ noted the New York Herald. ‘Their bonnets alone represent a price which a few years since would more than have paid for an entire outfit. Silks, satins and laces have risen in price to an extent which would seem beyond the means of any save millionaires, and yet the sale of these articles is greater than ever.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

As often seems to happen in periods of intense social mobility, a self-defined social elite emerged quite suddenly, as those who had been there longest, and felt they had the best claim to be top of the pile, pulled up the social ladder. It was the queen of this society resistance movement who swept up the aisle of St Thomas Church as guest of honour at Consuelo’s wedding on 6 November 1895. Mrs Caroline Schermerhorn Backhouse Astor, the Mrs Astor, was born into the Schermerhorns, an old Dutch family who were already entertaining and patronising the arts when the Commodore started the Dispatch Line. A generation older than Alva (there was a twenty-three year difference), Caroline married new money in the form of William Backhouse Astor in 1853. She immediately set about de-vulgarising Mr Astor, whose fortune was derived from furs, pianos and Manhattan slums. She persuaded him to drop the ‘Backhouse’ and ‘Jr’ and moved him north to 350 Fifth Avenue. This house famously had a ballroom into which she could squeeze 400 people, eventually giving rise to the idea that New York’s elite comprised ‘the Four Hundred’.

(#litres_trial_promo)