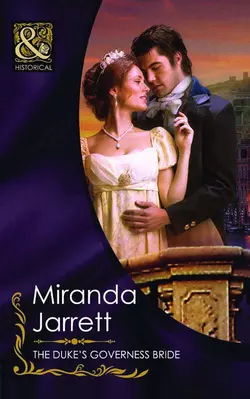

The Duke′s Governess Bride

Miranda Jarrett

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Prim governessFormer governess Jane Wood is on borrowed time – and she doesn’t want the fairytale of her Grand Tour to end. She awaits the arrival of her employer, Richard Farren, Duke of Aston, with trepidation. . .Passionate mistress To widower Richard, meek and mousy Miss Wood is unrecognisable as the carefree and passionate Jane. Seeing Venice through her eyes opens his mind and heart to romance!Proper wifeYet a sinister threat hangs over their new-found happiness: to protect Jane, Richard will have to overcome the demons of his past and persuade her to become his proper wife. . .