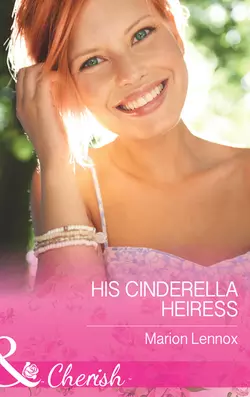

His Cinderella Heiress

Marion Lennox

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 465.10 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A castle to call home…After years in foster care, Jo Conaill has never settled anywhere. Travelling to Ireland to claim a surprise inheritance – a castle! – is a chance to reconnect with her past. And when she’s rescued by handsome landowner Finn, their sizzling chemistry is undeniable…Except Finn turns out to be Lord of Glenconaill, who she must share her inheritance with! Jo has no plans to stay, but living in the castle with gorgeous Finn is an unexpected temptation. Has she found the home she’s always craved in Finn’s arms…?