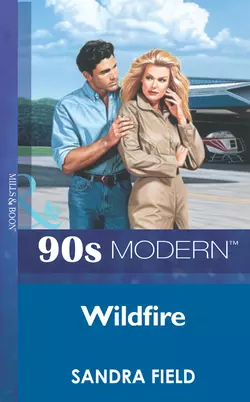

Wildfire

Sandra Field

T.N.T. Simon Greywood had been a volunteer fire fighter for just one day, but he knew a hot spot when he saw one - and her name was Shea Mallory.She was argumentative, stubborn, cantankerous, and she wasn't about to let him get within striking distance. As the area's most seasoned helicopter pilot, Shea's determination to avoid Simon was impossible. It was her job to fly fire fighters to the fire.And though she was a consummate risk taker on the job, she kept her heart away from hazards - until Simon's kiss sparked something that threatened to burn like wildfire… .

Wildfire

Sandra Field

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE (#u1359154c-79d4-50f3-b05a-aaf6bf5d5948)

CHAPTER TWO (#uc7be30ff-a40c-5017-8e70-1d7963952357)

CHAPTER THREE (#u83745d6b-e8a3-5239-8892-14d863121af1)

CHAPTER FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE

HE WAS in love.

Smiling to himself, Simon Greywood rested his paddle across the gunwales, the canoe sliding silently through the mirror-smooth water. It was early enough in the morning that mist, cool and intangible, was still rising from the lake, wreathing the reeds and granite boulders that edged the shore in phantasmagorical folds. Although birds were singing in the forest, some of them so sweetly that they made his throat ache, their cries merely scratched the surface of a silence so absolute as to be a force in itself.

The silence of wilderness, he thought. A wilderness as different from the city he had left only two weeks ago as could be imagined. In London, no matter what the hour of day or night, there was always the underlying snarl of traffic, the sense of people pressing in on all sides...whereas here, on a lake deep in the Nova Scotian forest, there was not another human being in sight. He loved it here. Felt almost as though in some strange way he had come home.

From the corner of his eye he caught movement. A wet brown head was swimming purposefully towards him, churning a V-shaped wake in the water. Wondering if it could be a beaver, for Jim had told him there was a dam in the stillwater near the head of the lake, Simon sat motionless. Within fifteen feet of the canoe the animal suddenly veered away from him, slapped its tail on the lake with a crack like a gunshot, and in a flurry of spray dived beneath the water.

The tail had been broad and flat, highly effective as a warning signal. So it was a beaver. Chuckling softly, Simon picked up his paddle again and stroked through the channel between the two lakes, carefully avoiding a couple of rocks that lay just below the surface. The water level was down, Jim had told him, because it had been such a hot, dry summer.

He had not paddled as far as this second lake before. What had Jim called it? Maynard’s Lake? Not a name that in any way expressed the serene beauty of the still, dark water that reflected in perfect symmetry the rocks and trees surrounding the lake and the small white clouds that hung above it.

Following the shore, he worked on the Indian stroke that Jim had been teaching him, a stroke that enabled him to stay on course without ever lifting the paddle out of the water and thus to move as silently as was possible. Best way to come across wildlife, Jim had assured him, describing how he had once got within forty feet of a moose by using that particular stroke.

The shoreline meandered down the lake in a series of coves, each lush with ferns and the pink blooms of bog laurel. The mist was slowly dissipating as the sun gained warmth. All the tensions that had driven Simon for as many years as he could remember seemed to be seeping away under the morning’s spell; he felt utterly at peace in a way that was new to him. And he had Jim to thank for it. Jim, his brother, from whom he had been separated for nearly twenty-five years...

A series of loud splashes came from the next cove, shattering the quiet and his own reflective mood; it was as though some large animal had entered the water and was wading through it. A moose? A bear? In spite of himself, Simon felt a shiver of atavistic fear ripple along his nerves. He might feel as though he was at home here. But in terms of actual experience of the wilderness he was a raw beginner. He’d do well to remember that.

He edged nearer the granite boulders that hid him from view of the next cove. There was a gap between the rocks, too narrow for his canoe, but wide enough that he should be able to see what was causing the disturbance without himself being seen. Sculling gently, he came parallel with the gap, and as he did so the splashing ceased with dramatic suddenness.

He had not dreamed it, though. The surface of the water in the cove was stirred into ripples and tiny wavelets, on which the lily pads placidly bobbed. But of the perpetrator of the ripples there was no sign.

Moose, he was almost sure, did not dive. Did bears? He had no idea. Holding himself ready to do a swift backup stroke if the situation called for it, Simon waited to see what creature would emerge from the lake. Another beaver? A loon?

A head broke the surface, swimming away from him. Long hair streamed from the skull back into the water as, in a smooth, sinuous curve of naked flesh, the woman dived beneath the lake again. Tiny air bubbles rose to the top, and the ripples spread slowly outwards.

Simon took a deep breath, wondering if he was indeed dreaming. He had been under the impression that Jim’s cabin was the last little outpost of civilisation on this chain of lakes; certainly his brother had not mentioned that anyone else lived further out then he. So who was this woman, who had appeared and disappeared like some spirit of the lake?

As if in answer to his question, she burst up out of the water again, her profile to him this time, the sun glinting on her wet cheeks and white teeth, for she was smiling in sheer pleasure. The force of her stroke brought, momentarily, the gleam of her shoulders and the smooth swell of her breasts into sight, inexpressibly beautiful. Then, in a flash of bare thighs, she knifed below the water.

His nails digging into the polished shaft of his paddle, Simon waited for her to reappear. When she did, she was facing him. But the rising sun was full in her face, and he was sure he was invisible to her.

He knew two things with an immediacy that knocked him off balance.

First, of course, he knew he did not want to disturb her in her play; for play it was, as innocent and joyful as that of a young otter. To frighten her, or alert her to his presence, was the last thing he wanted.

He could not tell what colour her eyes were, nor her hair, clinging as it was to her head. Nor, even with his artist’s trained eye, could he discern details of her face: she was too far away, and the sun shone too brightly on her features. What he received was an impression of both motion and emotion, of vivid life intensely embodied. She was a creature of the moment, this woman. Most certainly she was no lake spirit. That was too ethereal a designation by far. She was a woman of flesh and blood who was, he would be willing to bet, as much in love with life as he himself was in love with the wilderness.

As she rolled over on to her back with easy grace and began splashing away from him, her breasts hidden in the spray and then exposed to the sun, their pink tips shining wetly, he admitted to himself what the second thing was. He desired her. Instantly and unequivocally, as he had not desired a woman for a long time. If he were to obey his instincts he would drive the canoe around the rocks, scoop her up and then make love to her with a passion he’d thought he had lost.

Sure, Simon, a voice jeered in his ear. Canoes aren’t designed for lovemaking. Both of you would end up in the lake. Anyway, a woman as vital as that one might want to choose her partner herself. Assuming she hasn’t already got one. Get real, as Jim would say.

The woman rolled over on to her stomach, her spine a long, entrancing curve. But her mood had changed from play to work. For nearly fifteen minutes she swam back and forth parallel to the shore with a businesslike crawl, all her movements supple and strong. Then, diving again, she headed towards the shore.

Simon had sat as still as a statue for the entire fifteen minutes. He now brought the canoe round so as not to lose sight of her. Part of him was ashamed that he should watch her like any peeping Tom; particularly when in such a setting she could not possibly be expecting anyone within miles of her. Intuitively he was sure she would not have played so artlessly in the water had she suspected human eyes were on her. But he could not help himself. Formidable as his will-power could be, and he knew just how formidable better than any other human being, it was not strong enough to make him drag his eyes away from her.

His mouth dry, he watched her get to her feet, the water waist-deep, waves caressing her hips. Her hair reached halfway down her back. Tossing her head, she flicked it back, before wading to the small sand beach at the furthest point of the cove.

She moved beautifully, with an unselfconscious grace that brought a lump to his throat. When she reached the sand, she stooped to pick up a bright red towel that was lying there. But instead of walking towards the trees she turned briefly to face the lake, the towel hanging from one hand like an ancient banner of war. Throwing back her head, she gave a delicious peal of laughter, in which was all her joy in the freshness of morning and the pleasure of her solitary swim.

The sound struck Simon to the heart, for in it was a quality that he had ground to dust in his own soul during the last ten years. He felt involuntary tears prick at the back of his eyes, and furiously willed them back. The woman had wrapped the towel around her body and was loping up the sand towards a venerable pine tree that overhung the beach. For the first time he saw, tucked among the tree-trunks, a weathered cabin with a wide veranda and a stone chimney. Even as he watched, she disappeared among the trees in a flutter of scarlet. A few moments later he heard a screen door bang shut.

Simon let out his breath in a long sigh. His emotions were in chaos, a chaos he had no wish to analyse. He needed to get out of here. He needed to go back to Jim’s cabin, to the world that was sane and normal and known. As he picked up his paddle, he briefly looked down into the water to check for rocks, and saw in its mirror his own face. It looked no different from the way it usually did; somehow he would have expected the last few minutes to have marked it in some way.

His hair was thick and unruly, blacker than the surface of the lake, while his eyes, in startling contrast, were as blue as a summer sky. His will-power, which had driven him for so many years, was matched by the hard line of his jaw and the uncompromising jut of his nose, features that gave his face character rather than conventional good looks. That he was attractive to women he had long known and never really understood. His eye for detail failed him when it came to his own countenance: he was blind to the hint of sensuality in his mouth, to all the shadings of emotion that his eyes could express, to the thickness of his dark lashes which contrasted so intriguingly with the strength in his cheekbones.

He might not understand why women gravitated to him. He did know that there had never been a woman he had chosen to pursue who had not gone willingly to his bed. Willingly and soon. This he had come to take for granted. What it had meant was that he had slept with very few women in the last number of years, because what was easy and available was not always what was desired.

Scowling down at his face, Simon plunged the paddle into the water so that the reflection disappeared in a swirl of ripples. He brought the canoe around with a couple of strong sweeps, then began stroking back down the lake as though all the demons of the underworld were after him, digging his blade into the water so hard that his wake was marked by miniature black whirlpools.

He had been in danger of being sucked into such a whirlpool, he thought savagely, navigating the channel into the next lake with less than his usual caution. So he had seen a naked woman swimming in a lake. So what? He had seen naked women before. Seen them, painted them, made love to some of them. There was no reason for him suddenly to be feeling as though he was the only man in a world newly created, and she the one woman fashioned for his delight. No reason for him to feel as though all the warmth of the sun had fallen into his lap, like a gift of the gods. No reason at all. He was thirty-five years old, experienced and wise in the ways of the world. He was not sixteen.

As though mocking him, his inner eye presented him with a graphic image of the woman’s sensuous play in the water, of her pleasure-drenched smile and her water-streaked breasts. It was an image that made nonsense of reason in a way that both infuriated and frightened him. Apart from anything else, he had no idea who she was. Perhaps she was a visitor who would be gone from here by the weekend. Perhaps she was happily married. Perhaps he would never see her again. And even if he did, would he recognise her?

Only if she’s naked, the little voice sneered in his ear.

Go away, he growled. This is ridiculous! It makes no difference whether she’s from Vancouver with a husband and ten children or from Halifax with a live-in boyfriend. He, Simon, had not come to Canada to get involved with a woman. He had come to get acquainted with his brother; and to break away from a city that had been stifling him. This unknown woman was nothing to him. Nothing!

Driven by his own thoughts, and despite the headwind that had sprung up, Simon made it back to Jim’s cabin in record time. Physical action, as always, had made him feel better. Grinning ruefully to himself as he felt the twinges in his shoulder muscles, he tied the canoe to the dock. Then he strode up the path to the deck, took the steps in two quick leaps, and pulled open the screen door. It slammed shut behind him with a sound that struck into his memory: just so had another door on another cabin slammed shut half an hour ago.

Determined not to allow that aberrant turmoil of emotion to seize him again, equally determined not to ask a single question about the woman who lived in the cabin on Maynard’s Lake, he said, ‘Mmm...smells good.’

Jim was frying bacon in a cast-iron pan on the gas stove; his cabin, for all its rustic air, had all the modern conveniences. Turning over a rasher with a fork, he said casually, ‘You must have gone quite a way...see anything interesting?’

Jim was all that Simon was not, and in a group of people they would never have been taken for brothers. Ten years younger, four inches shorter, tow-haired where Simon had black hair, Jim had a sunny smile and an open nature, as far from the man of secrets that was his elder brother as a man could be. Jim was like a tabby cat stretched out in a patch of sunlight on the floor, purring in contentment; whereas Simon was like a wildcat, wary, deep-hidden in the shadows of the forest.

‘I went as far as Maynard’s Lake,’ Simon replied. ‘Shall I put some toast on?’

‘Sure...how’s your J-stroke doing?’

Simon grinned. ‘I’ll have you know that I can actually canoe in a straight line, brother dear.’ He cut four slices of the thick molasses bread that was sold at the nearest bakery. ‘I might marry the woman who makes this bread,’ he added.

‘You can’t,’ Jim said amiably. ‘She’s married to the local police chief who also happens to be the county’s champion arm wrestler. Pass me the eggs, would you?’

As Simon took the carton of farm eggs out of the refrigerator and handed them to his brother, he said awkwardly, ‘You’re a good teacher, Jim. Two weeks ago I’d never even been in a canoe. You’ve spent a lot of time with me—thanks.’

Jim shot him a keen glance. But all he said was, ‘You’re welcome. Can’t have you going back to England never having experienced something as quintessentially Canadian as canoeing.’

‘I even saw a beaver this morning. Plus several hundred maple trees.’

‘Then you’re practically a native,’ Jim laughed. Cracking a couple of eggs into the pan, he added, ‘As I recall, the best canoe lesson we had was the one on rescue techniques—that was the morning you turned into a human being.’

After a tiny hesitation Simon said evenly, ‘You believe in direct speech, don’t you?’

‘I say it like it is, yeah...life’s too short for anything else. The first three or four days you were here I figured it was going to be one hell of a long summer.’

Simon remembered the lesson on rescue all too well. It had involved him standing upright in one canoe pulling Jim’s swamped canoe up over the gunwales, and later hauling his brother out of the water, too. Jim had been pretending to be panic-stricken; it had been an interesting few minutes. Certainly it had been the day when the first of the barriers between the two men had fallen to the ground; Jim’s memory was entirely accurate. ‘Do you still feel that way? About the long summer, I mean.’

‘No. Although, like an iceberg, nine-tenths of you stays beneath the surface.’

‘That’s the way I live,’ Simon said, exasperated.

Expertly Jim flipped the eggs over. ‘That the reason it took you the best part of six weeks to answer my letter?’

Simon very carefully buttered the toast, taking his time. He said finally, ‘When I first got here, I mentioned that things hadn’t been going well for me lately. I’m in a rut as far as my painting’s concerned, London feels like a prison—dammit, I don’t even want to talk about it!’

He paused, knowing he had been guilty of understatement. For the last six months he had quite literally found himself unable to paint. In the north light of his studio he had spent hours standing in front of a blank canvas, paralysed by its whiteness, its emptiness, its mute quality of waiting. Since the age of sixteen he had lived to paint. To find himself cut off from his life’s blood had terrified him. And the more terrified he had become, the less able he had been even to hold a brush, let alone use it.

He took a ragged breath, knowing he had to pick up the thread of his story. ‘When your letter came in April, it took me totally by surprise. I’d tried to trace you once, years ago, but the records had been destroyed in a fire, and that was that. There was nothing more I could do. So when I heard from you it was like a voice from the past. I wasn’t even sure I wanted to look at that past. Not in the shape I was in. So I didn’t answer your letter right away, no.’ He added irritably, ‘Those eggs are going to be as hard as rocks.’

Jim drained the fat from the eggs and put them on the plates along with some bacon. ‘When you didn’t answer, I thought you didn’t want anything to do with me.’

‘That’s not true—’

‘After all, who needs a stray brother four thousand miles away?’

‘I never felt that way, Jim,’ Simon said forcefully. ‘I came, didn’t I? I’m here.’ He ran his fingers through his hair. ‘Look, I know I’m not the easiest man in the world to get along with. I spend a lot of time alone—I have to. But I’m glad we’ve met again. Glad we’re getting to know each other. Just give me time, that’s all.’

‘We’ve got all summer. If you want to stay that long.’

Simon put the toast on the table along with a pot of strawberry jam that had also come from the bakery. This was a moment of decision for both him and his brother, he knew, nor did he minimise the importance of that decision. It was not an opportune time for an image of a woman playing naked in a mist-wreathed lake to flicker into his brain. Shoving it back, he said quietly, ‘I’d like to stay, yes. You can always kick me out if you get sick of me.’

‘I’ll do that,’ Jim promised, a smile splitting his pleasant, suntanned face. ‘Let’s eat.’

The eggs were not overdone, and there were huge whole strawberries in the jam. Refilling the coffee-mugs, Simon said, ‘I’ll get fat if I stay all summer.’

Jim shot a derisive glance at his brother’s lean length in the chair. ‘Sure. Anyway, if this dry weather keeps up, there’s a way you can lose weight. If you want to.’

‘What’s that?’ Simon said lazily. ‘Canoe races between here and the bakery.’

‘Fire-fighting.’

About to laugh, Simon saw that Jim was not joking. ‘Where’s the fire?’ he said semi-facetiously.

‘The woods are like tinder right now. We had less snow than normal last winter, and almost no rain all spring. A cigarette dropped in the bracken, a lightning strike—that’s all it would take. I’m on the volunteer fire department here, and we help out the whole county. They’re running a course next week on ground fire-fighting. Want to take it?’

The part of Simon that had felt for months like a lion trapped in a cage said instantly, ‘Yes.’

‘Great. I’ll sign you up.’

‘So you spend your winters teaching junior high school and your summers fighting fires?’ Simon said quizzically. ‘That’s quite a combination.’

‘Fighting fires is a breeze after some of the kids I’ve got. Anyway, I love the woods. If I can save even an acre from burning, that’s worth a lot to me.’

Every window in Jim’s cabin opened into the trees: the drooping boughs of hemlock, the brilliant green of beech, the thin-slivered needles of pine. To think of all these myriad shades of green engulfed in flame and reduced to charred blackness hurt something deep inside Simon. He said with utter conviction, ‘I already love this place.’

‘I was afraid you’d hate it here,’ Jim confessed. ‘I wondered if we should have stayed in my apartment in Halifax all summer—it’s a city, after all, even if it is pretty small beer compared with London.’

‘I came here to get away from cities.’

‘But you haven’t painted anything since you got here.’

Simon’s face closed. Fighting to keep any emotion from his voice, he said, ‘No.’

‘Well, I sure bumped into the glacier there,’ Jim said cheerfully and unrepentantly. ‘I’ve got to go into town this morning and pick up a few supplies...want to come?’

Town was the little village of Somerville, population seven hundred and fifty. ‘Not really. I’ll clean up the dishes, and then I’ll read for a while.’

‘Once I get back, we should go for a swim—it’s going to be another scorcher of a day.’ Jim reached for the shopping list that was taped to the door of the refrigerator.

Would he ever be able to swim again without thinking of a woman’s nude body playing in the water? To his horror Simon heard himself say, ‘I’d thought there wasn’t another cabin further out than this one. But I saw a place on Maynard’s Lake in one of the coves.’

‘Oh, that’s Shea’s cabin.’

‘Shay?’ Simon repeated, puzzled.

‘Spelled S.H.E.A. but pronounced “shay”. She’s a good friend of mine. You’ll meet her sooner or later.’

‘What do you mean by good friend?’ Simon said carefully. Of all the scenarios he had pictured, that the unknown woman might be involved with his brother had not been one of them.

‘Just what I say. When I was fourteen and she was eighteen, I was madly in love with her...after all, who wasn’t? But by the time I’d got my teaching degrees I’d met Sally, and Shea kind of dropped into the background in any romantic sense.’ His voice a touch overly casual, he added, ‘You’d probably like her.’

‘Matchmaking?’ Simon asked, a little too sharply for his own liking.

Jim gave a snort of laughter. ‘You don’t know Shea! She’s not into being matchmade. If there is such a word.’

Simon did a quick calculation. ‘So at twenty-nine she’s still unattached.’

‘Yeah. Just like you at thirty-five.’

‘Anyone ever tell you that you can be decidedly aggravating, James Hanrahan?’

‘Sally does. Frequently.’ Restlessly Jim got up from his chair. ‘I’ll be glad when she gets home. It seems like an age since I’ve seen her.’

Sally, like Jim, was a teacher; they had met in university and had taught together in an isolated outpost on Baffin Island. But Sally had stayed on there when Jim had got his present job in Halifax, and was only now transferring to a school just outside the city. She was presently visiting her parents in Montreal, and then her sisters in New Brunswick, and would not arrive in Nova Scotia for another month. Jim, plainly, was finding the delay hard to take. ‘Do you want to marry her?’ Simon asked bluntly.

Jim nodded. ‘If she’ll have me. Isolation postings do kind of throw people together, and she thinks we should take the winter to get reacquainted.’

‘Makes sense.’

‘Sense doesn’t have much to do with the way I feel around Sally. You ever feel that way about a woman, Simon?’

Yes, Simon thought. This morning, when I saw a woman called Shea playing in the lake. ‘I’ve never married,’ he said evasively. ‘Too busy getting to the top. The women I go out with are the decorative, sophisticated ones that a man in my position is supposed to be seen with. You know, the kind that get photographed in the glossy fashion magazines. Wouldn’t be caught dead without at least a quarter of an inch of make-up on. Wouldn’t be caught dead without an escort who wasn’t at the top, either,’ he finished cynically.

‘Doesn’t sound as though you like any of them very much,’ Jim observed.

‘Liking is not what it’s about.’ Simon pushed back from the table. ‘Hell, I didn’t even like myself very much. And that is the last remark of a personal nature that you’re getting out of me today.’

‘OK, OK,’ Jim said, slapping the back pocket of his jeans to see if he had his wallet. ‘Although if you’re into that kind of woman, Shea is definitely not the one for you... Want anything at the store?’

‘No, thanks.’

Simon started stacking the plates, and a few moments later heard Jim’s truck drive away down the dirt lane that linked them to the highway. So the lissom swimmer in Maynard’s Lake was called Shea. She was twenty-nine years old, unattached, and, if he could trust the intonation in Jim’s voice, a very independent lady. Apparently he was going to meet her, sooner or later.

In his brother’s opinion she was not the right woman for him.

Or else he was the wrong man.

CHAPTER TWO

AT FIRST glimpse the scene in front of him was one of utter confusion. Simon stood beside Jim’s truck in his jeans and T-shirt and new steel-toed boots, taking everything in, and gradually the various components began to make sense. The weather-beaten building on the far side of the road appeared to be functioning as dormitory, kitchen, and command post; two men with sleeping rolls disappeared inside it, and from it wafted the smell of chicken soup. Heaps of gear stood around in the dust: pumps, shovels, chainsaws, and big yellow bags of hose. He remembered those long lines of hose from the course he had so light-heartedly agreed to take. Filled with water, they were astoundingly heavy.

From behind the building he heard the decelerating whine of a helicopter engine. Helicopters, he now knew, were used for water-bombing and for transporting ground crew to fires unreachable by road. The truck parked near Jim’s had a shiny aluminium water tank, and the volunteer fire truck behind it carried a portable tank. Two bulldozers were lined up further down the track.

His gaze shifted, almost unwillingly, to the west. There, on the horizon, was the reason he was here.

The smoke was yellow more than blue, a thick, ominous cloud over gently rolling hills. He had somehow expected the smoke to be lying still, crouched like a predator over its prey. Instead it was full of roiling movement, billowing high into the sky. Although he was too far away to see flames, the surging smoke alone was enough to make his heart beat faster.

Jim was jogging back towards the truck. ‘I checked in with the fire boss,’ he said as soon as he was in earshot. ‘Four of us are going to do mop-up on the flank that’s furthest from the road—you want to take a run down to the helicopter and find out from the pilot how soon we can go? I’ll grab a couple of bunks in the meantime.’

Glad to have something tangible to do, Simon headed across the dirt road. The dozers had pushed it further to the west, in a tumble of rocks and earth. Better a helicopter than drive on that, he thought, nodding at three men in filthy orange suits who had just come out of the command post. Their faces were covered with soot, their eyes red-rimmed, and again he felt his heartbeat quicken. London, more than ever, seemed like another world. He was suddenly, fiercely glad to be here. Whatever he was to do in the next twenty-four hours would be real and useful.

More so than putting pigment on canvas.

He went past the corner of the building. The engine of the helicopter had been turned off and the blades were still. It did not look large enough to carry four men and a pilot.

Simon walked round the nose. Someone was balancing on the narrow step that was two feet from the ground, and was reaching into the cabin. With a jolt of surprise he saw that the body in the dirt-streaked beige flying suit was definitely not a male body; the curves under the cotton fabric were female curves, and the waist far too slender to belong to a man. All the warnings of sabotage so liberally posted in Heathrow Airport rose in Simon’s mind. He said sharply, ‘What are you doing here? Get out of that cabin!’

The body went absolutely still. Then the woman turned to look at him. Her eyes the cold grey of a November sky, she said precisely, ‘I beg your pardon?’

‘You heard me—you’re trespassing.’

In a single lithe movement that brought a frown to his face, so familiar did it seem, she jumped to the ground. ‘I’m not in the mood for jokes,’ she said. ‘What do you want?’

‘I came here to tell the pilot that four of us need transport out to the south flank of the fire—’

‘OK,’ she said impatiently, ‘you’ve told her. We can—’

‘You’re the pilot,’ Simon said blankly.

‘I’m the pilot,’ she repeated, unsmiling. ‘I’m not in the mood for chauvinist remarks, either.’

He had not been about to make any. Although his assumption that a pilot had to be a man was about as chauvinistic as he could get.

For a moment Simon regarded her in silence. She looked tired and dirty and hot. While her hair, tawny-blonde, was pulled back into a ribbon, wisps of it stuck to her face; there were shadows like bruises under the level grey eyes. Her nose had an interesting bump in it, and her mouth was too generous for true beauty. He wanted very badly to make that mouth smile.

He said straightforwardly, ‘I’m sorry. I should never have assumed that you had to be a man.’

She gave him the briefest of nods. ‘OK. We can leave in about half an hour. I have to refuel first.’

Turning away from him, she knelt down to unlatch the cargo pod in the belly of the helicopter. Plainly he was dismissed. Yet something in the way she moved, in her slimness and the curve of her back, made Simon say with a gaucheness rare to him, ‘I don’t know your name.’

She was hauling a fuel pump from the pod. Resting it on the ground by one of the skids, she brushed her hands down her trousers and stood up. She was tall, perhaps five feet nine. He liked tall women. ‘Shea Mallory,’ she said.

Shea...he could not have come across two women named Shea in the space of three weeks. He croaked, ‘Do you have a cabin on Maynard’s Lake?’

She frowned at him. ‘Yes,’ she said in a clipped voice. ‘How do you know that? I’ve never laid eyes on you before.’

She had not laid eyes on him. But he most certainly had laid eyes on her. Although his heart was banging against his ribs, at another level Simon was not even surprised to learn her identity, for every movement she had made in the last few minutes had told him who she was. Feeling colour creep up his neck, fighting to keep his voice casual, he said, ‘I’m Simon Greywood. Jim Hanrahan’s brother.’ He held out his hand.

Shea took it with noticeable reluctance and gave it the lightest of pressures before releasing it. ‘The one from England,’ she said. ‘The artist.’

‘That’s right,’ he said, smiling at her in a way a number of women in London would have recognised. ‘I’m here for the summer.’

She did not smile back. Instead she gave his spanking-new T-shirt a derisive glance. ‘Aren’t you afraid you’ll get your hands dirty?’

He felt his temper rise. ‘I did apologise for my mistake.’

‘I wasn’t referring to that particular mistake.’

‘So what have you got against me, Shea Mallory?’

‘I’ll tell you,’ she answered, scowling at him as she thrust her hands in the pockets of her trousers. ‘I helped Jim write that first letter to you, so I know how much it meant to him. His parents didn’t tell him he was adopted until he turned twenty-five...once he discovered he had an older brother, he wanted to get in touch with you right away. So he wrote to you. And for six weeks you didn’t even bother to write back.’

‘That’s true,’ Simon said shortly. ‘But—’

‘With all the money you’ve got, I would have thought you could have picked up the phone—seeing that you were too busy painting rich people to write a letter.’

‘This is really none of your business—it’s between Jim and me, and nothing to do with you.’

She raised her voice over the growl of an approaching truck. ‘He and I went canoeing four weeks after he wrote to you. He was really upset—and he’s my friend. In my book that makes it my business.’ She glanced to her right. ‘Now you’ll have to excuse me, that’s the truck with the oil drums. Be back here at quarter-past nine.’

The truck lurched down the track and came to a stop three feet from where Simon was standing. The driver gave Shea a cheery hello and climbed out. Simon, knowing he had definitely got the worst of that round, strode up the hill to find his brother.

Jim was standing by a pile of gear chatting to two other men, whom he introduced as Charlie and Steve. Simon said, ‘We leave at nine-fifteen.’

‘We’ve got time for a coffee, then,’ Steve said, and headed for the kitchen, Charlie hard on his heels.

‘Jim, why the devil didn’t you tell me Shea was the pilot?’ Simon demanded.

Jim blinked. ‘For one thing, I didn’t know...there are seven or eight different pilots. For another, I didn’t want to engineer any kind of an introduction and be accused of matchmaking.’

‘You don’t have to worry—she can’t stand the sight of me.’

‘Whyever not?’

‘She thinks I should have picked up the telephone the minute I got your letter.’

‘That’s not exactly her business,’ Jim said thoughtfully.

‘That’s what I told her. Which didn’t endear me to her.’

‘Oh, well, I suspected she might not be the woman for you,’ Jim said with a dismissiveness that grated on Simon’s nerves. ‘Why don’t we grab a coffee and a doughnut before we go? It’s going to be a long day.’

Simon subdued various replies, making a manful effort to pull his mind off an encounter that had left him as stirred up as an adolescent. ‘Won’t we need gear out there?’ he asked.

‘The Bell—the big helicopter—took it out half an hour ago along with another crew. This isn’t a bad fire, as forest fires go...a good way for you to get your feet wet.’

The fire was not foremost in Simon’s mind. He had now seen two sides of the woman called Shea: the laughing creature playing in the water, and the cold-eyed pilot of a government helicopter. Although he was still smarting from her rebuff, this did not in any way diminish his desire to find out more about her. Both sides of her had got under his skin. Nor, he was sure, were these two facets of her personality the whole woman.

Besides which, he was determined to make her smile.

At him.

* * *

At nine-fifteen the four men headed towards the helicopter, Simon now arrayed in his orange overalls and carrying his hard hat and ear protectors. The sharp tang of smoke filled the air.

Shea was sitting in the helicopter doing her pre-flight check. Without making it at all obvious Simon engineered it that he was the one to sit beside her in the front. After doing up his seatbelt, he put on the headset, prepared to enjoy himself. The cockpit was small, so he was sitting quite close to her. Unlike the women he was accustomed to, she did not smell of expensive perfume. She smelled of woodsmoke.

She checked over her shoulder to see that she had her four passengers. Then, all her movements calm and unhurried, she flipped a number of switches and opened the throttle. The blades started to whirl, faster and faster, and the cockpit jounced up and down. After waiting a couple of minutes for the starter to cool, she turned the generator on, wound to full throttle and did the last of her checks.

Then her voice came over Simon’s headset. ‘Patrol three to fire boss. Taking off with four mop-up crew for the south flank of the fire. Over.’

‘OK, patrol three. The Bambi’s out there already. Proceed to the head of the fire for water drops. Over.’

‘Roger, fire boss. Over and out.’

The Bambi, Simon knew from his course, was the brand name for the water-bombing bucket. His muddled feelings for the woman beside him coalescing into simple admiration for her skill, he watched as she eased up on the throttle with her left hand, her feet adjusting the anti-torque pedals. As gently as a bird, the helicopter lifted from the ground, the dust swirling from the downdraught. She turned the nose into the wind, picked up the rpm’s, and with her right hand on the cyclic drove the machine forward and up. Feeling much as he had on his first plane trip, Simon saw the depot fall behind them, the trees diminishing to little green sticks, the dozer road to a narrow brown thread.

He said spontaneously, ‘How long have you been a pilot?’

‘Four years on helicopters. Three years fixed-wing before that.’

As she brought the helicopter round in a steep turn to face the fire, his shoulder brushed hers. The contact shivered along his nerves, much as the ripples had spread over the surface of the lake. Because her shirt-sleeves were rolled up, he could see the dusting of blonde hair on her arms, and the play of tendons in her wrists as she made the constant small adjustments to the controls. She wore no rings. Her fingernails were rimed with soot.

Why dirty fingernails should fill him with an emotion he could only call tenderness Simon had no idea. Fully aware that everyone on board could hear him, he said tritely, ‘You like flying.’

‘I love it,’ she said. ‘It’s what I like to do best in the world.’

The fire was closer now, so that Simon could see its charred perimeters and the columns of smoke shot through with leaping flames. I want to make love with you, Shea Mallory, he thought. I don’t know when or where or how. But I know it’s going to happen. I’m going to make you laugh with passion and cry out with desire, your cool grey eyes warming to me like mist burning off the lake in the sun. And you’ll find there’s something else you like to do the best in the world.

Deliberately he leaned his shoulder into hers again, and with a quiver of primitive triumph saw her lashes flicker and felt her muscles tense against his. So she was not as unaware of him as she might wish to appear.

But when she spoke into the intercom she glanced over her shoulder, and her voice was utterly impersonal. ‘We’ll land in that bog to the right of the perimeter—the gear is stashed near by, and the ground’s dry.’

She was addressing all four of them, not him alone. Simon’s lips quirked. He liked an opponent of mettle. Larissa, his companion of the last several months, would never have reprimanded him about Jim as Shea had, and certainly would never have been seen with dirty fingernails. Larissa was an ambitious young model who had liked him for his fame and money, in turn furnishing Simon with her ornamental person at all the right parties. While the gossip columnists would have been flabbergasted to know they had never been lovers, Simon by then was just starting to acknowledge how badly askew his life had become, and was not about to encumber himself with a love-affair. As for Larissa, she was quite shrewd enough to know that the appearance of an affair could be just as useful as the affair itself. Yet the few decorative tears she had let fall at a farewell dinner for him had by no means been fake.

Shea’s shoulder twisted against his as she checked the visibility around her. ‘Fire boss, this is patrol three coming in to land. Over.’

‘We read you, patrol three. Over.’

Again, fascinated, Simon watched the interplay of feet and hands as Shea eased the helicopter down towards the bog. The tangle of alders and tamaracks grew closer and the long green grass fanned out in the wind. The landing was flawless. Over the intercom she said, ‘Keep low when you get out, and don’t go near the tail rotor or the exhaust. Good luck, fellows.’

Simon unbuckled his belt, sliding the shoulder harness over the back of his seat. But before he took off the headset he said sincerely, ‘Thanks, Shea—my first helicopter ride, and with a real pro.’

As if she was surprised by the compliment, she glanced sideways at him. A flash of sardonic humour crossed her face. ‘Hope your first fire goes as smoothly,’ she said.

He held her gaze. ‘Do you ever smile?’

She raised her brows in mockery. ‘At my friends.’

‘You and I aren’t through with each other. You know that, don’t you?’

She said gently, ‘You’re holding up the fire crew, Mr Greywood. Goodbye.’

‘There’s an expression I’ve picked up from my brother that I like a lot better than goodbye. See you, Shea Mallory.’

He got up, bent low because the cockpit wasn’t constructed with six-foot-two men in mind, and with exaggerated care laid the headset on the seat. Even though he had had the last word, he suspected round two had gone to her, too.

Why then did he feel so exhilarated?

He swung himself down to the ground. Crouching, he ran beyond the whirling disc of the blades, the wind flattening his clothing to his body, the noise deafening. Two Lands and Forests employees who had been standing near by hurried towards the helicopter, dragging a large orange pleated bucket; Shea raised her machine five feet off the ground and the men, wearing gloves against static, attached the metal cables of the bucket to the belly of the helicopter. When the job was done the helicopter rose into the sky, the bucket dangling incongruously, like a child’s toy.

One of the men grinned at Jim. ‘You have to be careful doin’ that—if the cables get caught in the skids, you got a crash on your hands. You guys headin’ out for mop-up? Your gear’s just beyond that clump of trees. We’re joinin’ up with another bunch thataway. See ya.’

See you, Simon had said to Shea; but the helicopter was now lost in the smoke and his confidence seemed utterly misplaced and his exhilaration as childish as the Bambi bucket. One small word had banished them both. Crash, the man had said, as casually as if he were discussing the weather.

Accidents happen. Helicopters crash. Simon strained his eyes to see through the thick blanket of smoke.

‘Coming?’ Jim said.

With a jerk Simon came back to the present. Shea, cool, competent Shea, would be truly insulted if she knew he was worrying about her crashing, he thought wryly, and forced his mind to the job at hand. And there it stayed for the next eleven hours. Each man was given a sector to work at the tail of the fire, that desolate, charred acreage where the fire had already passed. Simon dug up tree roots where embers could be smouldering; he chopped down snags; he set fires to burn out the few remaining patches of green; he felt for hot spots in the soil where fire could be burning underground and burst to the surface days or weeks later.

It was a hard, tedious job, without a vestige of glamour. Because daily workouts in a gym in London had been part of his routine, Simon was very fit. Nevertheless, by nine o’clock that evening when the beat of an approaching helicopter signalled the end of their day, every muscle and bone in his body was aching with fatigue.

At intervals throughout the day he had caught the distant mutter of an engine, and had seen Shea’s blue helicopter swinging round the head of the fire with its load of water. Now he was almost relieved to see that it was not Shea’s small machine but the larger Bell that was sinking down into the clearing near the small knot of men. He didn’t have the energy to deal with Shea right now, he thought, heaving himself aboard. All he wanted to do was sleep.

The Bell disgorged them behind the command post. ‘Great way to spend a Saturday evening, eh?’ Jim said, a grin splitting his blackened face. ‘You OK?’

‘Do I look as bad as you?’

‘I’ve seen you look better...there’s a lake half a mile down the road, we could take the truck and go for a swim.’

‘Don’t know if I’ve got the energy,’ Simon groaned. ‘Is this how you Canadians separate the men from the boys?’

A light female voice said, ‘It’s one of the ways. Hi there, Jim, how did it go?’

‘Good,’ Jim said, and rather heavy-handedly began talking to the man with Shea, a tall, good-looking man in a beige flying suit like Shea’s.

Said Simon, ‘Good in no way describes the day I’ve had. But you, Shea, look good.’

She was wearing jeans and a flowered shirt, her tawny hair loose on her shoulders in an untidy mass of curls that softened the severity of her expression. He added, ‘That was a compliment. You could smile.’

‘You’re persistent, aren’t you?’

‘Tenacious as the British bulldog, that’s me,’ Simon said. ‘How was your day?’

‘Great. The fire’s under control—got stopped at the firebreak. So now there’ll be lots more work for you,’ she finished limpidly.

Jim and the pilot had moved away. ‘Unemployment is beginning to seem like an attractive option,’ Simon said.

‘I didn’t think you’d stick with it,’ she flashed.

‘I’d hate to prove you wrong.’

‘Be honest, Simon,’ she retorted. ‘You’d love to prove me wrong.’

It was the first time she had used his name. He liked the sound of it on her tongue. Very much. What the devil was happening to him? She was an argumentative, unfriendly and judgemental woman. Why should he care what she called him? ‘If I stick with it, will you smile at me?’ he asked.

He saw laughter, as swift as lightning, flash across her eyes. She said primly, ‘I don’t make promises that I might not keep. And I distrust charm.’

‘I have lots of sterling virtues—I don’t drink to excess, I don’t do drugs, and I pay my taxes.’

‘And,’ she said shrewdly, ‘you’re used to women falling all over you.’

‘You could try it some time,’ he said hopefully.

‘I never liked being one of a crowd.’

His eyes very blue in his filthy face, Simon started to laugh. ‘I think a woman would have to be pretty desperate to fall all over me right now. I stink.’

‘You do,’ she said.

‘Hey—you’ve agreed with something I’ve said. We’re making progress.’

Glowering at him, she snapped, ‘We are not! You can’t make progress if you’re not going anywhere.’ Looking round, she added with asperity, ‘Where’s Michael gone? We’re supposed to—’

‘Is he your boyfriend?’ Simon interrupted.

‘No.’

Until she spoke he was not aware how much the sight of the good-looking pilot at her side had disturbed him. He said indirectly, ‘I hate coy women.’

‘You like complaisant women, Mr Greywood.’

‘Then you’re a new experience for me, Ms Mallory... Michael’s over by the oil drums.’

She tossed her head, turned on her heel, and stalked over to the stack of oil drums. Well pleased with himself, Simon headed for the kitchen, and when Jim joined him a few minutes later said, ‘I could do with a swim—you still interested in going?’

‘Sure,’ Jim said. ‘What did you say to make Shea look like a firecracker about to explode?’

‘I have no idea,’ Simon said blandly. ‘But thank you for diverting the estimable Michael.’

Jim put a hand on his arm and said soberly, ‘Don’t play games with Shea, Simon. She’s not one of your sophisticated types—she could get hurt.’

‘She’s not going to let me get near enough to hurt her.’ Simon shifted his sore shoulders restlessly. ‘Let’s go for that swim.’

CHAPTER THREE

THREE days passed, hot, cloudless days where the wind blew ashes in ghostly whorls among the charred stumps and fanned the flames of back fires. Simon’s muscles grew accustomed to the hours of hard labour, labour which he was finding oddly satisfying. There was nothing romantic about mopping up after a fire. But he knew he was protecting the unburned woods from further outbreaks, and that pleased him inordinately. Not even the news on the second day that the fire had leaped the break and was again out of control could entirely dissipate his pleasure in a job as far removed from painting portraits as he could imagine.

Mopping up certainly didn’t give him the time or the energy to sit around and brood about his creativity. Or rather his lack of it.

Only two things were bothering him. The majority of the men were holding back from him; and Shea was avoiding him.

As he stooped to pour fuel into his chainsaw he remembered the conversation he had overheard in the dark woods by the lake the very first evening he had been here. He had been sitting on the grass doing up his boots when he had heard one of the other swimmers say from behind a clump of trees, ‘Who’s the new guy?’

‘Jim Hanrahan’s brother,’ Steve had replied.

‘Don’t look like a brother of Jim’s to me. Speaks kind of funny—like he’s royalty.’

‘He’s from England,’ Steve said.

A third, derogatory voice said, ‘He’s a painter.’

‘Nothin’ wrong with that,’ the first voice responded. ‘I’ve painted a house or two in my day.’

‘Pictures, Joe,’ the third voice said. ‘Pictures that you hang on the wall.’

‘Oh,’ said Joe.

‘He did just fine on the job today,’ Steve put in. ‘You get used to the way he talks after a while.’

‘Yeah?’ Joe said dubiously. ‘Well, we’ll see how long he lasts...’

This conversation had struck a chord in Simon, who had already noticed how some of the crew were ignoring him and how he was always on the fringe of their horseplay; and the next three days merely confirmed that impression. Jim had not been much help. ‘You’re different,’ he said. ‘You’re a rich and famous artist, totally outside their experience. They don’t know what to do with you, so they act as if you’re not there. They’ll get over it.’

As he capped the fuel can, Simon wondered how many more days he’d have to spend mopping up before he was allowed to join their ranks. While it was an exclusion he understood, he could have done without it.

As for Shea, she was spending long hours water-bombing, and Michael did most of the ground crew drops. In her off-hours, whether she was eating, talking, or playing cards, she always seemed to be surrounded by men. As the lone woman in a male environment, the deft way she handled them was admirable. But he was beginning to feel like a large and hungry dog whose chain was too short to reach the feed dish.

He scrambled up the side of a hill to cut down six or seven blackened tree stumps, and half an hour later was on his way back to the base. Michael was the pilot.

Because he was far less tired now than he had been the first day, Simon headed for the command post to check on the fire’s progress. The fire boss was talking on the radio, and waved at him genially, and two other ground crew nodded at him. As he bent over the infra-red maps he heard Shea’s voice coming from the next room. It took him a moment to realise she was using the telephone.

‘No, I can’t get away—the fire’s still out of control. But I’ll be off next weekend, because I’ll be up to maximum hours by then.

‘I didn’t promise!

‘Peter, I told you when we first met that in the summer I don’t have a schedule, I just have to go where the work is. That’s the way it is.

‘I am not married to a helicopter! But this is how I earn my living. Look, there’s no point fighting about this—couldn’t we meet on Saturday as we’d planned?

‘I see. I really hate this, Peter—’

There was a sudden silence, as though the man at the other end had slammed down the phone. A few moments later Shea marched through the room, saying crisply to the fire boss, ‘Thanks for the use of the phone, Brad.’

In one swift glance Simon had seen her flushed cheeks and brilliant eyes. Not sure if it was rage or tears that had given them their sheen, he kept his eyes assiduously on the map. The door swung shut behind her, and as if in sympathy the radio crackled with static. Simon finished what he was doing and went to find his brother for a swim. He hoped it hadn’t been tears.

As always, the cool water of the lake felt like the nearest thing to heaven. Afterwards Simon hauled on a pair of clean jeans and his running shoes, relishing the breeze on his bare chest. He angled up the hill to where he had parked the truck; Jim had been roped into a poker game back at the base. Eight or nine of the ground crew were standing between him and the truck, including two men new to Simon. There was a litter of empty beer cans on the ground.

‘Who’s the blonde?’ one of the new men asked, tipping back a can to drain it.

Steve answered. ‘Name’s Shea Mallory, Everett. She’s a helicopter pilot.’

‘No kidding. She ever go swimming?’

There was a warning note in Steve’s voice. ‘She goes up at the other end of the lake, and we stay at this end.’

Everett was patently unimpressed. ‘Yeah? Now if I met her down by the lake, let me tell you what I’d do to her—’

His string of obscenities fell on Simon’s ears like live coals. Not even stopping to think, he dropped his shirt and towel on the path. In a blur of movement he seized Everett by the shirt-front, lifting him clear off the ground. ‘You listen to me,’ he snarled. ‘If I ever see you within ten feet of Shea Mallory, I’ll drive you straight into the middle of next week.’

‘I didn’t—’

‘Do you hear me?’ Simon shook the man as if he were a bundle of old rags. ‘Or do I have to show you that I mean business?’

‘Yeah, I hear you. I was only kidding; no need to—’

His muscles pulsing with fury, Simon grated, ‘And I don’t want you ever mentioning her name again. Have you got that, too?’

‘Sure. Sure thing.’

Feeling the sour taste of rage in his mouth, Simon shoved the man away. Everett staggered, belched, and edged himself to the very back of the small group of men. Into the small, gratified silence Steve said with genuine warmth, ‘Good move, Simon. Want a beer?’

Simon’s heart was pounding as hard as though he had indeed come across Everett mistreating Shea. But he was quite well able to recognise what the offer of a beer represented. He had been accepted. He was now one of the crew. ‘Thanks,’ he said, nodding at Steve.

The beer slid down his throat, loosening the tension in his muscles. Joe started telling a very funny story about a fire-fighter and a porcupine, then Steve described a moose in rutting season who had kept him in the branches of a pine tree for over eight hours. Simon, feeling he had to keep his end up, told them about a bad-tempered stag he had come across when he was sketching in the Scottish highlands, and finished his beer. Declining Charlie’s offer of a second, he asked if anyone wanted a drive back to the base. ‘We’re gonna finish up the beer before we head back,’ Joe said. ‘Brad don’t like us to drink in the bunkhouse. See you later, Simon.’

There was a chorus of grunts and goodbyes. Feeling as though he had won a major victory, Simon got in the truck and drove away from the lake. His headlights bounced on the ruts and potholes; the only other light came from the dull red glow of the fire on the horizon, and the far-away glitter of the stars. The trees that crowded to the ditch were blacker than the sky, he thought absently, easing the truck over a ridge of dirt baked hard as stone, and enjoying the cool air on his bare chest. He’d left his shirt and towel behind, he realised ruefully. Maybe Everett would bring them back for him. Then again, maybe he wouldn’t.

His foot suddenly found the brakes, his eyes peering through the dusty windscreen into the woods. He’d seen a flicker of white move through the trees, he’d swear he had.

It must have been a deer. They had white tails.

But the brief image Simon had glimpsed from the corner of his eye did not fit that of a deer. He let the truck jounce down the hill and round the next corner, and then came to a halt and turned off the engine. After opening the door very quietly, he slid to the ground, and pushed it shut without letting the catch click. Keeping to the grass verge, letting his eyes adjust to the dark, he rounded the corner and began creeping back up the hill the way he had come.

His trainers rustled in the grass. A bough brushed his shoulder, and a mosquito whined in his ear. The stars were dazzlingly bright. Maybe he’d imagined that flicker of movement, he thought. The fight with Everett had got his adrenalin going and his imagination had done the rest.

He stopped in the shadow of a fir tree, inhaling the tang of its resin, his fingers brushing the living green of its needles. He had seen too many dead trees the last few days, smelled too much smoke...

To his left a branch cracked and footsteps came towards him through the trees. Footsteps that were making no effort at concealment.

All the hairs rose on his neck. He stood still as a statue, scarcely breathing, and saw a slim figure emerge from the trees. It scrambled down the ditch, up the other side, and on to the road.

‘Hello, Shea,’ he said.

She gave a shriek of terror and whirled to face him. She was wearing a white shirt, a small haversack slung over one shoulder.

Quickly Simon stepped out on the road. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said, ‘I didn’t mean to scare you. I saw you from the truck—or at least I saw something, I didn’t know it was you.’

‘Do you always creep up on people like that?’ she said shakily.

He came closer to her. Her eyes were wide-held and the pulse was racing at the base of her throat. ‘You were hiding in the woods,’ he said. ‘Why?’

‘No, I wasn’t!’

‘Come on, Shea.’

She swallowed, and tried again. ‘OK, so I was. I wanted to walk back to the base, that’s all. By myself.’

‘You were swimming?’ Simon asked, thinking furiously.

‘Yes. Steve gave me a ride up to the far end of the lake, but I told him I’d find my own way home.’ She looked straight at him, her eyes black like the sky. ‘I really want to be alone, Simon...it’s only a ten-minute walk.’

He said quietly, ‘You overheard Everett.’

‘No!’ She caught herself, but not quickly enough. ‘I don’t know what you mean.’

‘Are you angry with me because I interfered?’

Her eyes dropped from his face to his chest, with its tangle of dark hair over muscles hard as boards, then skidded upwards again. ‘Don’t you have a shirt?’ she said fretfully.

‘I couldn’t hold my towel, my shirt and Everett all at once,’ he said. ‘And in the excitement of the moment I left the shirt back there on the bank. Don’t change the subject.’

She shoved her hands in the pockets of her jeans, hunching her shoulders and staring past him into the dark woods. ‘Yes, I heard him.’

‘He’d had a couple of beers too many, Shea.’

‘So is that supposed to excuse him?’ she retorted.

‘Nothing excuses what he said.’

In such a low voice that he had to strain to hear her, she said, ‘He made me feel dirty all over.’

She looked heart-stoppingly vulnerable, a side of her he had never seen before. As gently as if she were a fawn he might startle with his touch, he slid his hands down her arms, cupped her elbows in his palms, and discovered that she was shivering. ‘You’re cold,’ he said, concern for her overriding the urgent need to pull her in his arms and hold her. ‘Let’s go to the truck. I’m pretty sure Jim left his jacket on the seat.’

She was now staring at his chin, and he was not sure she had even heard him. ‘I love my job!’ she burst out. ‘I already told you that—I can’t imagine doing anything else. But do you have any idea how hard it is to be the only woman in a world of men—day after day, night after night? I’m the only female pilot in the province. And you saw how many women there are in the ground crew—none. I get so sick of men sometimes!’

‘Sick of men like Everett. Joe and Brad and Steve—they wouldn’t lay a finger on you.’

‘I know that, of course I do.’ She bent her head. ‘Everett stood next to me at breakfast this morning—he looked at me as though he was undressing me; it was horrible.’

She suddenly pulled away from him, scrubbing at her eyes with her fists. ‘I loathe weepy women,’ she gulped.

‘Oh, hell,’ Simon said violently. Forgetting restraint, he took her by the shoulders, drew her to his chest and held her, rocking her back and forth. ‘I’m sorry you overheard Everett, Shea, and I swear he’ll never look at you again like that. Not if I’m anywhere in range.’

‘You did sound fairly convincing,’ she muttered.

He could feel the tiny warm puffs of her breath on his skin. Fighting to keep his head, aware through every nerve in his body how beautifully she fitted into his arms, he said, ‘And I’m more than sorry about that stupid mistake I made at the helicopter the first time I met you.’

She raised her head, looking full at him, and suddenly smiled, her mouth a generous curve. ‘I think you redeemed yourself tonight—thanks.’

His breath caught in his throat. She had smiled at him, and he wanted to kiss her so badly, he ached with the need. He said huskily, ‘You’re beautiful when you smile, Shea—it was worth waiting for.’

Her palms were resting flat on his chest, the imprint of each of her fingers burning into his skin. Her smile faded, and she suddenly pushed back from him. ‘This is crazy,’ she said breathlessly; ‘I don’t even like you!’

It was as if she had taken a knife and thrust it in his belly. His lashes flickered. She added incoherently, ‘Don’t look like that, Simon! I—’

He didn’t want her to know that she had hurt him. That he was vulnerable to a woman he scarcely knew. A woman, moreover, who could not by any stretch of the imagination be accused of leading him on. ‘Come on, I’ll drive you back to the base,’ he said, his arms dropping to his sides as he took a step back from her.

She grabbed him by the arm, giving it a little shake, and said in an impassioned rush of words, ‘What I meant was that I didn’t like you when I first met you and then there was that whole business of the letter to Jim. But I do know how hard you’ve worked since you got here and I know Everett won’t bother me again, nor any of the others very likely, and I haven’t even thanked you properly.’

He glanced down. Her nails were digging into his flesh. Her fingers were not long and tapering like Larissa’s, but shorter, and somehow capable-looking. He remembered how, all too briefly, they had lain against his chest, and in his imagination he could picture them elsewhere on his body, holding him, caressing him. His loins stirred. Very deliberately he rested his own hand over hers, holding it captive, playing with her fingers, and the whole time his gaze was trained on her face.

Her eyes widened perceptibly. Surrender, pleasure, and panic chased across her face in rapid succession, before she tugged her hand free and jammed it in her pocket. She said with the kind of rawness that bespoke complete honesty, ‘I’ve never met anyone like you before.’

He said, groping for the truth himself, ‘Maybe that’s because you’ve been waiting for me.’

‘Simon, I don’t like this conversation one bit! If the offer’s still open to drive me back to the base, let’s go. If not, I’m walking back right now.’

He could not possibly hold her here against her will, not with Everett’s words so fresh in both their minds. ‘The offer’s open. And I meant what I said.’ And, he added silently to himself, maybe I’ve been waiting for you, too.

She was staring at him so stormily that every instinct in him screamed at him to take her into his arms and kiss her until her body melted into his. Gritting his teeth, he turned away and almost ran down the hill, his trainers crunching in the gravel.

You’re a fool, Simon Greywood. It might be a week before you get her on her own again. A week. Or never.

From behind him, Shea panted, ‘Slow down! We are not—at this precise moment—on our way to a fire.’

He gave a reluctant laugh, waiting until she had come alongside him. ‘I’ve never met anyone like you before, either,’ he said.

She stood stock-still in the middle of the road, her hands on her hips. ‘I can think of any number of fascinating topics of discussion, Simon. The weather. The safety regulations for ground crew. The flight operational directives for water drops, section seven of the provincial government manual. Even, God forbid, Everett. What we don’t have to talk about is you and me. Us. There isn’t any us!’

‘I don’t believe that,’ Simon said flatly.

‘You’d better! Because it’s true.’

‘Close your eyes,’ he said affably, ‘and I’ll prove you wrong.’

Her nostrils flared. ‘I wasn’t born yesterday.’

‘If there’s no us, you’ve got nothing to be afraid of. I’m not Everett, Shea.’

‘You’re a lot more dangerous than Everett,’ she said tightly.

‘Am I now? But if there’s one thing I’m sure about, it’s that you’re no coward, Shea Mallory. Close your eyes.’

She said obliquely, ‘The phone call that I assume you overheard this evening, there being no such thing as privacy at the base camp, signalled the end of yet another relationship in my life. My job comes first in the summer, and men don’t like that.’

‘To quote a woman I know, I don’t like being one of the crowd. Close your eyes.’

‘I never could resist a dare...’ With a loud sigh she scrunched her eyes shut. Very softly Simon stepped closer. Cupping her face in his hands, he leaned forward and kissed her on the mouth.

He felt the shock run through her body. With exquisite gentleness he moved his lips against hers, warming them, wanting only to give her pleasure. He sensed her yielding, then, as heat spread through his limbs, her first, tentative response.

It slammed through his body. One of his hands moved to the back of her head, burying itself in the luxuriant mass of her hair, still damp from the lake. His kiss deepened, fierce in its demand. And for a few heart-stopping moments Shea met him in that new place, looping her arms around his neck and opening to him with a generosity that made his senses swim.

Through her thin shirt her breasts were pressed against his naked torso. He remembered her nude form rising from the lake, sunlight dancing on her wet skin, and with his tongue sought out the sweetness of her mouth.

She wrenched free of him, and over the clamour of blood in his veins he heard her quickened breathing. ‘Simon, I—we can’t do this!’

He said roughly, ‘Kissing you feels more right than anything I’ve done in the last ten years,’ and knew his words for the simple truth.

‘Please...take me home.’

‘At least admit there’s something between us, Shea!’

‘I’m twenty-nine years old, not nineteen, and I know about sex,’ she said wildly. ‘You’re an attractive man and it’s a beautiful night and we’re alone...what happened is perfectly natural. Plus it’s a very long time since I’ve been to bed with anyone.’

Discovering that he liked that last piece of information quite a lot, Simon said, ‘The same is true for me.’

‘There you are, then,’ she said.

‘It wouldn’t matter if I’d taken a dozen women to bed in the last forty-eight hours,’ he said in exasperation. ‘This isn’t just about sex.’

‘For me it is.’

‘You’ve got to be the most argumentative, stubborn and cantankerous woman I’ve ever come across!’

‘Good. Then you’ll keep away from me from now on—because I’d sure appreciate it if you did.’

Furious with her, yet simultaneously lanced by a pain out of all proportion that she could say such a thing, Simon said levelly, ‘You don’t really mean that.’

She raised her chin defiantly. ‘Yes, I do.’

‘For God’s sake give us half a chance!’

Each word falling like a stone to the ground, she said, ‘I don’t want to. And I’ve already told you there’s no such thing as us. There’s just a separate you and a separate me—do you get it?’

Her voice had risen. ‘You’re dead wrong,’ Simon said harshly. ‘We could make something—’

‘No! Because I don’t want to. Don’t you understand basic English, Simon Greywood?’

‘You’re making a huge mistake.’

‘You’re just not used to a woman saying no.’

As he winced at her accuracy, she added with a satisfaction that lacerated his nerves, ‘See, I was right.’ Spacing her words, she finished, ‘I want you to leave me alone. That’s all. It doesn’t seem like a very difficult concept.’

Simon looked at her in silence. She meant every word she had said, he thought heavily. According to her, she was deprived sexually, she found him physically attractive, and the velvet darkness of the night had done the rest. So she had also been telling the truth earlier, when she had said she didn’t like him. Liking, he had often thought, was at least as important as that elusive emotion called love.

Unable to tolerate her physical closeness, hating the seethe of emotion red-hot in his chest, he rapped, ‘The truck’s parked round the corner—let’s go.’ Without waiting to see if she was following, he set off down the road.

When he climbed in and turned on the ignition she was only moments behind him. He drove back to the base as fast as was safe, pulled up behind Brad’s car, and got out. ‘I’m going to watch the poker game for a while,’ he said. ‘Goodnight.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/sandra-field/wildfire/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Sandra Field

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.26 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: T.N.T. Simon Greywood had been a volunteer fire fighter for just one day, but he knew a hot spot when he saw one – and her name was Shea Mallory.She was argumentative, stubborn, cantankerous, and she wasn′t about to let him get within striking distance. As the area′s most seasoned helicopter pilot, Shea′s determination to avoid Simon was impossible. It was her job to fly fire fighters to the fire.And though she was a consummate risk taker on the job, she kept her heart away from hazards – until Simon′s kiss sparked something that threatened to burn like wildfire… .