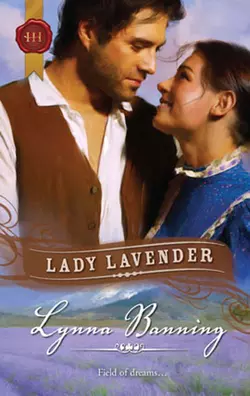

Lady Lavender

Lynna Banning

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.26 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Indulge your fantasies of delicious Regency Rakes, fierce Viking warriors and rugged Highlanders. Be swept away into a world of intense passion, lavish settings and romance that burns brightly through the centuriesLynna Banning is an «older,» retired woman who loves history, particularly the medieval and Old West periods. She was a professional editor for 30-plus years, taught high school English and upon early retirement in 1993, she began writing fiction. She found it wasn′t easy. How-to books, workshops, conferences and sweaty hours with pen in hand finally led to a completed novel, which was rejected. But they asked for «what else did she have?» and thus was born her first published book, Western Rose, a tale of the Old West (Oregon frontier) and, loosely, the story of her grandparents′ courtship.An amateur pianist and harpsichordist, Lynna performs on harp, psaltery and percussion instruments in a medieval music ensemble.She enjoys hearing from her readers; you may write directly to P. O. Box 324, Felton CA 95018, or e-mail carolynw@cruzio. com.You can also visit Lynna′s Web site at www. lynnabanning. com.