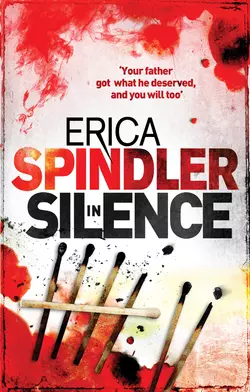

In Silence

Erica Spindler

Journalist Avery Chauvin is devastated when she receives word of her father's suicide. How could her father, a dedicated physician, have taken his own life? That he set himself on fire is unfathomable.Returning to her hometown of Cypress Springs, Louisiana, Avery desperately searches for answers. Instead she hears whispered rumors of strange happenings, of neighbors who go missing in the night. She discovers a box of old newspaper articles in her father's house, all covering the horrific murder of a local woman. Why had her father kept them?Then the past and present collide. A woman is found brutally slain. An outsider passing through town vanishes. And Avery begins to wonder, could her father have been the victim of foul play?As each step closer to the truth exposes yet another layer of deceit, Avery must face the fact that in this peaceful Southern town a terrible evil resides, protected–until now–by the power of silence.

Critical acclaim for the novels of

ERICA SPINDLER

FORBIDDEN FRUIT

“… a high adventure of love’s triumph over twisted obsession.” —Publishers Weekly

“Outstanding! A first-rate romantic thriller.”

—Rendezvous

SHOCKING PINK

“… a compelling tale of kinky sex and murder.”

-Publishers Weekly

DEAD RUN

“… a classic confrontation between good and evil.”

—Publishers Weekly

ALL FALL DOWN

“… smooth, fast ride to the end. Spindler is at the controls, negotiating the curves with consummate skill.”

—John Lutz, author of Single White Female

CAUSE FOR ALARM

“Spindler’s latest moves fast and takes no prisoners. An intriguing look into the twisted mind of someone for whom murder is simply business.”

-Publishers Weekly

Already available in MIRA

Books byErica Spindler

RED

FORTUNE

CAUSE FOR ALARM

ALL FALL DOWN

BONE COLD

DEAD RUN

SHOCKING PINK

FORBIDDEN FRUIT

SEE JANE DIE

KILLER TAKES ALL

In Silence

>

Erica Spindler

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

“The cruellest lies are often told in silence.”

—Robert Louis Stevenson

Acknowledgments

I’ve become a bit of a fixture at a local coffeehouse, sitting in a quiet corner, feverishly tapping away at my laptop keyboard. I share this with you because many of the people who I intend to acknowledge here, I connected with while sitting in that corner. A friendlier bunch you won’t find; I think of us as “Cheers” for the caffeine set.

I continue to be humbled and amazed by the enthusiasm and generosity shown me by the various professionals I approach for information, hat in hand. Thank you one and all. Without your generous contribution of time, personal insights and professional expertise, In Silence would have been much more difficult to bring to life. I hope you are pleased with the way I used the fruits of your labor.

I begin with my fellow coffee addicts: Renee Plauché and Linda Daley, who blew me away with their generosity toward me, a total stranger. Renee, a University of New Orleans graduate student in counseling, overheard me discussing avenues to research mental illness and offered help. She went so far as to lend me her textbooks, including the DSM IV, (that I now know to be), the clinician’s guide to diagnosis. Likewise Linda, hearing that I was tackling the subject of suicide, offered to share the story of her own father’s suicide. With a master’s in psychology and couseling, she was able to give me both professional and personal insights into suicide and its emotional aftermath. Captains Ralph and Patrick Juneau, Jefferson Parish Fire Department, for the crash course on all things fire: from arson to turn-out gear. Stephanie Otto, nursing student, Charity School of Nursing, for on-the-spot medical terminology and procedure information.

From beyond the coffeehouse walls: Michael D. Defatta, chief deputy coroner, St. Tammany Parish Coroner’s Office, for taking time out of his busy schedule to meet and answer my questions about the role of the coroner in criminal investigations and forensic pathology, particularly as it applies to burn victims. Frank Jordan, director of Emergency Medical Services, Mandeville Fire District #4, for his explanation of death by fire. Mrs. Barbara Gould, wife of West Feliciana Parish coroner Dr. Alfred Gould, for the long chat and great quote. Pat McLaughlin, friend, fellow author and journalist, for giving me a glimpse into the mind of the investigative reporter. Tom Mincher, owner of America Hunter Gun and Archery Shop, for information about hunting rifles and ammunition.

Thanks to my friends and colleagues who not only make the journey a smooth one, but a heck of a lot of fun as well. The amazing Dianne Moggy and the entire MIRA crew. My assistant, Rajean Schulze. My agent, Evan Marshall. My publicist, Lori Ames.

To my family, without whose love and support the days would be long, indeed.

And last but unquestionably first, thanks to my God, the one responsible for it all.

PROLOGUE

Cypress Springs, Louisiana Thursday, October 17, 2002 3:30 a.m.

The one called the Gavel waited patiently. The woman would come soon, he knew. He had been watching her. Learning her schedule, her habits. Those of her neighbors as well.

Tonight she would learn the price of moral corruption.

He moved his gaze over the woman’s darkened bedroom. Garments strewn across the matted carpeting. Dresser top littered with an assortment of cosmetic bottles and jars, empty Diet Coke and Miller Lite cans, gum and candy wrappers. Cigarette butts spilled from an overflowing ashtray.

A pig as well as a whore.

Twin feelings of resignation and disgust flowed over him. Had he expected anything different from a woman like her? An alley cat who bedded a new man nearly every night?

He was neither prude nor saint. Nor was he naive. These days few waited for marriage to consummate their relationship. He could live with that; he understood physical urges.

But excesses such as hers would not be tolerated in Cypress Springs. The Seven had voted. It had been unanimous. As their leader, it was his responsibility to make her understand.

The Gavel glanced at the bedside clock. He had been waiting nearly an hour. It wouldn’t be long now. Tonight she had gone to CJ’s, a bar on the west side of town, one frequented by the hard-partying crowd. She had left with a man named DuBroc. As was her MO, they had gone to his place. To the Gavel’s knowledge, this was a first offense for DuBroc. He would be watched as well. And if necessary, warned.

From the front of the apartment came the sound of the door lock turning over. The door opening, then clicking shut. A shudder moved over him. Of distaste for the inevitable. He wasn’t a predator, as some might label him. Predators sought the small and weak, either to sustain themselves or for twisted self-gratification.

Nor was he a bloodthirsty monster or sadist.

He was an honorable man. God-fearing, law-abiding. A patriot.

But as were the other members of The Seven, he was a man driven to desperate measures. To protect and defend all he held dear.

Women like this one soiled the community, they contributed to the moral decay running rampant in the world.

They were not alone, of course. Those who drank to excess, those who lied, cheated, stole; those who broke not only the laws of man but those of God as well.

The Seven had formed to combat such corruptions. For the Gavel and his six generals, it wasn’t about punishing the sinful but about maintaining a way of life. A way of life Cypress Springs had enjoyed for over a hundred years. A community where people could still walk the streets at night, where neighbor helped neighbor, where family values were more than a phrase tossed about by political candidates.

Honesty. Integrity. The Golden Rule. All were alive and well in Cypress Springs. The Seven had dedicated themselves to ensuring it stayed that way.

The Gavel likened individual immorality to the flesh-eating bacteria that had been in the news so much a few years back. A fisherman had contracted necrotizing fasciitis through a small cut on his hand. Once introduced to the body, it ate its covering until only a putrid, grotesque patchwork remained. So, too, was the effect of individual immorality on a community. His job was to make certain that didn’t happen.

The Gavel listened intently. The woman hummed under her breath as she made her way toward the back of the apartment and the bedroom where he waited. The self-satisfied sound sickened him.

He eased to his feet, moved toward the door. She stepped through. He grabbed her from behind, dragged her to his chest and covered her mouth with one gloved hand to stifle her screams. She smelled of cheap perfume, cigarettes. Sex.

“Elaine St. Claire,” he said against her ear, voice muffled by the ski mask he wore. “You have been judged and found guilty. Of contributing to the moral decay of this community. Of attempting to cause the ruination of a way of life that has existed for over a century. You must pay the price.”

He forced her to the bed. She struggled against him, her attempts pitiable. A mouse battling a mountain lion.

He knew what she thought—that he meant to rape her. He would sooner castrate himself than to join with a woman such as her. Besides, what kind of punishment would that be? What kind of warning?

No, he had something much more memorable in mind for her.

He stopped a foot from the bed. With the hand covering her mouth, he forced her gaze down. To the mattress. And the gift he had made just for her.

He had fashioned the instrument out of a baseball bat, one of the miniature, commemorative ones fans bought in stadium gift shops. He had covered the bat with flattened tin cans—choosing Diet Coke, her soft drink of choice—peeling back V-shaped pieces of the metal to form a kind of sharp, scaly skin. The trickiest part had been the double-edged knife blade he had imbedded in the bat’s rounded tip.

He was aware of the exact moment she saw it. She stilled. Terror rippled over her—a new fear, one born from the horror of the unimaginable.

“For you, Elaine,” he whispered against her ear. “Since you love to fuck so much, your punishment will be to give you what you love.”

She recoiled and pressed herself against him. Her response pleased him and he smiled, the black ski mask stretching across his mouth with the movement.

He could almost pity her. Almost but not quite. She had brought this fate upon herself.

“I designed it to open you from cervix to throat,” he continued, then lowered his voice. “From the inside, Elaine. It will be an excruciating way to die. Organs torn to shreds from within. Massive bleeding will lead to shock. Then coma. And finally, death. Of course, by that point you will pray for death to take you.”

She made a sound, high and terrified. Trapped.

“Do you think it would be possible to be fucked to death, Elaine? Is that how you’d like to die?”

She fought as he inched her closer. “Imagine what it will feel like inside you, Elaine. To feel your insides being ripped to shreds, the pain, the helplessness. Knowing you’re going to die, wishing for death to come swiftly.”

He pressed his mouth closer to her ear. “But it won’t. Perhaps, mercifully, you’ll lose consciousness. Perhaps not. I could keep you alert, there are ways, you know. You’ll beg for mercy, pray for a miracle. No miracle will come. No hero rushing in to save the day. No one to hear your screams.”

She trembled so violently he had to hold her erect. Tears streamed down her cheeks.

“This will be your only warning,” he continued. “Leave Cypress Springs immediately. Quietly. Tell no one. Not your friends, your employer or landlord. If you speak to anyone, you’ll be killed. The police cannot help you, do not contact them. If you do, you’ll be killed. If you stay, you’ll be killed. Your death will be horrible, I promise you that.”

He released her and she crumpled into a heap on the floor. He stared down at her shaking form. “There are many of us and we are always watching. Do you understand, Elaine St. Claire?”

She didn’t answer and he bent, grabbed a handful of her hair and yanked her face up toward his. “Do you understand?”

“Y-yes,” she whispered. “Anythi … I’ll do … anything.”

A small smile twisted his lips. His generals would be pleased.

He released her. “Smart girl, Elaine. Don’t forget this warning. You’re now the master of your own fate.”

The Gavel retrieved the weapon and walked away. As he let himself out, the sound of her sobs echoed through the apartment.

CHAPTER 1

Cypress Springs, Louisiana Wednesday, March 5, 2003 2:30 p.m.

Avery Chauvin drew her rented SUV to a stop in front of Rauche’s Dry Goods store and stepped out. A humid breeze stirred against her damp neck and ruffled her short dark hair as she surveyed Main Street. Rauche’s still occupied this coveted corner of Main and First Streets, the Azalea Café still screamed for a coat of paint, Parish Bank hadn’t been swallowed by one of the huge banking conglomerates and the town square these establishments all circled was as shady and lovely as ever, the gazebo at its center a startlingly bright white.

Her absence hadn’t changed Cypress Springs at all, she thought. How could that be? It was as if the twelve years between now and when she had headed off to Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, returning only for holiday breaks, had been a dream. As if her life in Washington, D.C., was a figment of her imagination.

If they had been, her mother would be alive, the massive, unexpected stroke she had suffered eleven years in the future. And her father—

Pain rushed over her. Her head filled with her father’s voice, slightly distorted by the answering machine.

“Avery, sweetheart … It’s Dad. I was hoping … I need to talk to you. I was hoping—” Pause. “There’s something … I’ll … try later. Goodbye, pumpkin.”

If only she had taken that call. If only she had stopped, just for the time it would have taken to speak with him. Her story could have waited. The congressman who had finally decided to talk could have waited. A couple minutes. A couple minutes that might have changed everything.

Her thoughts raced forward, to the next morning, the call from Buddy Stevens. Family friend. Her dad’s lifelong best friend. Cypress Springs’ chief of police.

“Avery, it’s Buddy. I’ve got some … some bad news, baby girl. Your dad, he’s—”

Dead. Her dad was dead. Between the time her father had called her and the next morning, he had killed himself. Gone into his garage, doused himself with diesel fuel, then lit a match.

How could you do it, Dad? Why did you do it? You didn’t even say—

The short scream of a police siren interrupted her thoughts. Avery turned. A West Feliciana Parish sheriff’s cruiser rolled up behind her Blazer. An officer stepped out and started toward her.

She recognized the man by his long, lanky frame, the way he moved and held himself. Matt Stevens, childhood friend, high-school sweetheart, the guy she’d left behind to pursue her dream of journalism. She’d seen Matt only a handful of times since then, most recently at her mother’s funeral nearly a year ago. Buddy must have told him she was coming.

Avery held up a hand in greeting. Still handsome, she thought, watching him approach. Still the best catch in the parish. Or maybe that title no longer applied; he could be attached now.

He reached her, stopped but didn’t smile. “It’s good to see you, Avery.” She saw herself reflected in his mirrored sunglasses, smaller than any grown woman ought to be, her elfin looks accentuated by her pixie haircut and dark eyes, which were too big for her face.

“It’s good to see you, too, Matt.”

“Sorry about your dad. I feel real bad about how it all happened. Real bad.”

“Thanks, I … I appreciate you and Buddy taking care of Dad’s—” Her throat constricted; she pushed on, determined not to fall apart. “Dad’s remains,” she finished.

“It was the least we could do.” Matt looked away, then back, expression somber. “Were you able to reach your cousins in Denver?”

“Yes,” she managed, feeling lost. They were all the family she had left—a couple of distant cousins and their families. Everyone else was gone now.

“I loved him, too, Avery. I knew since your mom’s death he’d been … struggling, but I still can’t believe he did it. I feel like I should have seen how bad off he was. That I should have known.”

The tears came then, swamping her. She’d been his daughter. She was the guilty party. The one who should have known.

He reached a hand out. “It’s okay to cry, Avery.”

“No … I’ve already—” She cleared her throat, fighting for composure. “I need to arrange a … service. Do the Gallaghers still own—”

“Yes. Danny’s taken over for his father. He’s expecting your call. Pop told him you were getting in sometime today.”

She motioned to the cruiser. “You’re out of your jurisdiction.”

The sheriff’s department handled all the unincorporated areas of the parish. The Cypress Springs Police Department policed the city itself.

One corner of his mouth lifted. “Guilty as charged. I was hanging around, hoping to catch you before you went by the house.”

“I was heading there now. I just stopped to … because—” She bit the words back; she’d had no real reason for stopping, had simply responded to a whim.

He seemed to understand. “I’ll go with you.”

“That’s really sweet, Matt. But unnecessary.”

“I disagree.” When she tried to protest more, he cut her off. “It’s bad, Avery. I don’t think you should see it alone the first time. I’m following you,” he finished, voice gruff. “Whether you want me to or not.”

Avery held his gaze a moment, then nodded and wordlessly turned and climbed into the rented Blazer. She started up the vehicle and eased back onto Main Street. As she drove the three-quarters of a mile to the old residential section where she had grown up, she took a deep breath.

Her father had chosen the hour of his death well—the middle of the night when his neighbors were less likely to see or smell the fire. He’d used diesel fuel, most probably the arson investigators determined, because unlike gasoline, which burned off vapors, diesel ignited on contact.

A neighbor out for an early-morning jog had discovered the still smoldering garage. After trying to rouse her father, who he’d assumed to be in bed, asleep, he had called the fire department. The state arson investigator had been brought in. They in turn had called the coroner, who’d notified the Cypress Springs Police Department. In the end, her dad had been identified by his dental records.

Neither the autopsy nor CSPD investigation had turned up any indication of foul play. Nor had any known motives for murder materialized: Dr. Phillip Chauvin had been universally liked and respected. The police had officially ruled his death a suicide.

No note. No goodbye.

How could you do it, Dad? Why?

Avery reached her parents’ house and turned into the driveway. The lawn of the 1920s era Acadian needed mowing; the beds weeding; bushes trimming. Although early, the azaleas had begun to bloom. Soon the beds around the house would be a riot of pinks, ranging from icy pale to deep rose.

Her dad had loved his yard. Had spent weekends puttering and planting, primping. It all looked forlorn now, she thought. Overgrown and ignored.

Avery frowned. How long had it been since her father had tended his yard? she wondered. Longer than the two days he had been gone. That was obvious.

Further evidence of the emotional depths to which he had sunk. How could she have missed how depressed he had grown? Why hadn’t she sensed something was wrong during their frequent phone conversations?

Matt pulled in behind her. She took a deep breath and climbed out of her vehicle.

He met her, expression grim. “You’re certain you’re ready for this?”

“Do I have a choice?”

They both knew she didn’t and they started up the curving driveway, toward the detached garage. A separate structure, the garage nestled behind the main house. A covered walkway connected the two buildings.

As they neared the structure the smell of the fire grew stronger—not just of wood smoke, but of what she imagined was charred flesh and bone. As they turned the corner of the driveway she saw that a large, irregularly shaped black mark marred the doorway.

“The heat from the fire,” Matt explained. “It did more damage inside. Actually, it’s a wonder the building didn’t come down.”

A half-dozen years ago, while working for the Tribune, Avery had been assigned to cover a rash of fires that had plagued the Chicago area. It turned out the arsonist had been the estranged son of a firefighter, looking to punish his old man for kicking him out of the house. Unfortunately, the police hadn’t caught him before he’d been responsible for the deaths of six innocent people—one of them an infant.

Avery and Matt reached the garage. She steeled herself for what would come next. She understood how gruesome death by fire was.

Matt led her to the side door. Opened it. They stepped into the building. The smell crashed over her. As did the stark reality of her father’s last minutes. She imagined his screams as the flames engulfed him. As his skin began to melt. Avery brought a hand to her mouth, her gaze going to the large char mark on the concrete floor—the spot where her father had burned alive.

His suicide had been an act of not only despair but self-hatred as well.

She began to tremble. Her head grew light, her knees weak. Turning, she ran outside, to the azalea bushes with their burgeoning blossoms. She doubled over, struggling not to throw up. Not to fall apart.

Matt came up behind her. He laid a hand on her back.

Avery squeezed her eyes shut. “How could he do it, Matt?” She looked over her shoulder at him, vision blurred by tears. “It’s bad enough that he took his own life, but to do it like that? The pain … it would have been excruciating.”

“I don’t know what to say,” he murmured, tone gentle. “I don’t have any answers for you. I wish I did.”

She straightened, mustering anger. Denial. “My father loved life. He valued it. He was a doctor, for God’s sake. He’d devoted his life to preserving it.”

At Matt’s silence, she lashed out. “He was proud of himself and the choices he’d made. Proud of how he had lived. The man who did that hated himself. That wasn’t my dad.” She said it again, tone taking on a desperate edge. “It wasn’t, Matt.”

“Avery, you haven’t been—” He bit the words off and shifted his gaze, expression uncomfortable.

“What, Matt? I haven’t been what?”

“Around a lot lately.” He must have read the effect of his words in her expression and he caught her hands and held them tightly. “Your dad hadn’t been himself for a while. He’d withdrawn, from everybody. Stayed in his house for days. When he went out he didn’t speak. Would cross to the other side of the street to avoid conversation.”

How could she not have known? “When?” she asked, hurting. “When did this start?”

“I suppose about the time he gave up his practice.”

Just after her mother’s death.

“Why didn’t somebody call me? Why didn’t—” She bit the words back and pressed her trembling lips together.

He squeezed her fingers. “It wasn’t an overnight thing. At first he just seemed preoccupied. Or like he needed time to grieve. On his own. It wasn’t until recently that people began to talk.”

Avery turned her gaze to her father’s overgrown garden. No wonder, she thought.

“I’m sorry, Avery. We all are.”

She swung away from her old friend, working to hold on to her anger. Fighting tears.

She lost the battle.

“Aw, Avery. Geez.” Matt went to her, drew her into his arms, against his chest. She leaned into him, burying her face in his shoulder, crying like a baby.

He held her awkwardly. Stiffly. Every so often he patted her shoulder and murmured something comforting, though through her sobs she couldn’t make out what.

The intensity of her tears lessened, then stopped. She drew away from him, embarrassed. “Sorry about that. It’s … I thought I could handle it.”

“Cut yourself some slack, Avery. Frankly, if you could handle it, I’d be a little worried about you.”

Tears flooded her eyes once more and she brought her hand to her nose. “I need a tissue. Excuse me.”

She headed toward her car, aware of him following. There, she rummaged in her purse, coming up with a rumpled Kleenex. She blew her nose, dabbed at her eyes, then faced him once more. “How could I not have known how bad off he was? Am I that self-involved?”

“None of us knew,” he said gently. “And we saw him every day.”

“But I was his daughter. I should have been able to tell, should have heard it in his voice. In what he said. Or didn’t say.”

“It’s not your fault, Avery.”

“No?” She realized her hands were shaking and slipped them into her pockets. “But I can’t help wondering, if I had stayed in Cypress Springs, would he be alive today? If I’d given up my career and stayed after Mom’s death, would he have staved off the depression that caused him to do … this? If I had simply picked up the pho—”

She swallowed the words, unable to speak them aloud. She met his gaze. “It hurts so much.”

“Don’t do this to yourself. You can’t go back.”

“I can’t, can I?” She winced at the bitterness in her voice. “I loved my dad more than anyone in the world, yet I only came home a handful of times in all the years since college. Even after Mom died so suddenly and so horribly, leaving so much unresolved between us. That should have been a wake-up call, but it wasn’t.”

He didn’t respond and she continued. “I’ve got to live with that, don’t I?”

“No,” he corrected. “You have to learn from it. It’s where you go from here that counts now. Not where you’ve been.”

A group of teenagers barreled by in a pickup truck, their raucous laughter interrupting the charged moment. The pickup was followed by another group of teenagers, these in a bright-yellow convertible, top down.

Avery glanced at her watch. Three-thirty. The high school let out the same time as it had all those years ago.

Funny how some things could change so dramatically and others not at all.

“I should get back to work. You going to be okay?”

She nodded. “Thanks for baby-sitting me.”

“No thanks necessary.” He started for the car, then stopped and looked back at her. “I almost forgot, Mom and Dad are expecting you for dinner tonight.”

“Tonight? But I just got in.”

“Exactly. No way are Mom and Dad going to let you spend your first night home alone.”

“But—”

“You’re not in the big city anymore, Avery. Here, people take care of each other. Besides, you’re family.”

Home. Family. At that moment nothing sounded better than that. “I’ll be there. They still live at the ranch?” she asked, using the nickname they had given the Stevenses’ sprawling ranch-style home.

“Of course. Status quo is something you can count on in Cypress Springs.” He crossed to his vehicle, opened the door and looked back at her. “Is six too early?”

“It’ll be perfect.”

“Great.” He climbed into the cruiser, started it and began backing up. Halfway down the driveway he stopped and lowered his window. “Hunter’s back home,” he called. “I thought you might want to know.”

Avery stood rooted to the spot even after Matt’s cruiser disappeared from sight. Hunter? she thought, disbelieving. Matt’s fraternal twin brother and the third member of their triumvirate. Back in Cypress Springs? Last she’d heard, he’d been a partner at a prestigious New Orleans law firm.

Avery turned away from the road and toward her childhood home. Something had happened the summer she’d been fifteen, Hunter and Matt sixteen. A rift had grown between the brothers. Hunter had become increasingly aloof, angry. He and Matt had fought often and several times violently. The Stevenses’ house, which had always been a haven of warmth, laughter and love, had become a battleground. As if the animosity between the brothers had spilled over into all the family relationships.

At first Avery had been certain the bad feelings between the brothers would pass. They hadn’t. Hunter had left for college and never returned—not even for holidays.

Now he, like she, had come home to Cypress Springs. Odd, she thought. A weird coincidence. Perhaps tonight she would discover what had brought him back.

CHAPTER 2

At six sharp, Avery pulled up in front of the Stevenses’ house. Buddy Stevens, sitting on the front porch smoking a cigar, caught sight of her and lumbered to his feet. “There’s my girl!” he bellowed. “Home safe and sound!”

She hurried up the walk and was enfolded in his arms. A mountain of a man with a barrel chest and booming voice, he had been Cypress Springs’s chief of police for as long as she could remember. Although a by-the-books lawman who had as much give as a concrete block when it came to his town and crime, the Buddy Stevens she knew was just a big ol’ teddy bear. A hard-ass with a soft, squishy center and a heart of gold.

He hugged her tightly, then held her at arm’s length. He searched her gaze, his own filled with regret. “I’m sorry, baby girl. Damn sorry.”

A lump formed in her throat. She cleared it with difficulty. “I know, Buddy. I’m sorry, too.”

He hugged her again. “You’re too thin. And you look tired.”

She drew away, filled with affection for the man who had been nearly as important to her growing up as her own father. “Haven’t you heard? A woman can’t be too thin.”

“Big-city crapola.” He put out the stogie and led her inside, arm firmly around her shoulders. “Lilah!” he called. “Cherry! Look who the cat’s dragged in.”

Cherry, Matt and Hunter’s younger sister, appeared at the kitchen door. The awkward-looking twelve-year-old girl had grown into an uncommonly beautiful woman. Tall, with dark hair and eyes like her brothers, she had inherited her mother’s elegant features and pretty skin.

When she saw Avery she burst into a huge smile. “You made it. We’ve been worried sick.” She crossed to Avery and hugged her. “That’s no kind of a trip for a woman to make alone.”

Such an unenlightened comment coming from a woman in her twenties took Avery aback. But as Matt had said earlier, she wasn’t in the city anymore.

She hugged her back. “It wasn’t so bad. Cab to Dullas, nonstop flight to New Orleans, a rental car here. The most harrowing part was retrieving my luggage.”

“Big, tough career girl,” Buddy murmured, sounding anything but pleased. “I hope you had a cell phone.”

“Of course. Fully charged at all times.” She grinned up at him. “And, you’ll be happy to know, pepper spray in my purse.”

“Pepper spray? Whatever for?” This came from Lilah Stevens.

“Self-protection, Mama,” Cherry supplied, glancing over her shoulder at the older woman.

Lilah, still as trim and attractive as Avery remembered, crossed from the kitchen and caught Avery’s hands. “Self-protection? Well, you won’t be needing that here.” She searched Avery’s gaze. “Avery, sweetheart. Welcome home. How are you?”

Avery squeezed the other woman’s hands, tears pricking her eyes. “I’ve been better, thanks.”

“I’m so sorry, sweetheart. Sorrier than I can express.”

“I know. And that means a lot.”

From the other room came the sound of a timer going off. Lilah released Avery’s hands. “That’s the pie.”

The smells emanating from the kitchen were heavenly. Lilah Stevens had been the best cook in the parish and had consistently won baking prizes at the parish fair. Growing up, Avery had angled for a dinner invitation at every opportunity.

“What kind of pie?” she asked.

“Strawberry. I know peach is your favorite but it’s impossible to find a decent peach this time of year. And the first Louisiana berries are in. And delicious, I might add.”

“Silly woman,” Buddy interrupted. “The poor child is exhausted. Stop your yapping about produce and let the girl sit down.”

“Yapping?” She wagged a finger at him. “If you want pie, Mr. Stevens, you’ll have to get yourself down to the Azalea Café.”

He immediately looked contrite. “Sorry, sugar-sweet, you know I was just teasing.”

“Now I’m sugar-sweet, am I?” She rolled her eyes and turned back to Avery. “You see what I’ve put up with all these years?”

Avery laughed. She used to wish her parents could be more like Lilah and Buddy, openly affectionate and teasing. In all the years she had known the couple, all the time she had spent around their home, she had never heard them raise their voices at one another. And when they’d teased each other, like just now, their love and respect had always shown through.

In truth, Avery had often wished her mother could be more like Lilah. Good-natured, outgoing. A traditional woman comfortable in her own skin. One who had enjoyed her children, making a home for them and her husband.

It had seemed to Avery that her mother had enjoyed neither, though she had never said so aloud. Avery had sensed her mother’s frustration, her dissatisfaction with her place in the world.

No, Avery thought, that wasn’t quite right. She had been frustrated by her only child’s tomboyish ways and defiant streak. She had been disappointed in her daughter’s likes and dislikes, the choices she made.

In her mother’s eyes, Avery hadn’t measured up.

Lilah Stevens had never made Avery feel she lacked anything. To the contrary, Lilah had made her feel not only worthy but special as well.

“I do see,” Avery agreed, playing along. “It’s outrageous.”

“That it is.” Lilah waved them toward the living room. “Matt should be here any moment. All I have left to do is whip the potatoes and heat the French bread. Then we can eat.”

“Can I help?” Avery asked.

As she had known it would be, the woman’s answer was a definitive no. Buddy and Cherry led her to the living room. Avery sank onto the overstuffed couch, acknowledging exhaustion. She wished she could lean her head back, close her eyes and sleep for a week.

“You’ve barely changed,” Buddy said softly, tone wistful. “Same pretty, bright-eyed girl you were the day you left Cypress Springs.”

She’d been so damn young back then. So ridiculously naive. She had yearned for something bigger than Cypress Springs, something better. Had sensed something important waited for her outside this small town. She supposed she had found it: a prestigious job; writing awards and professional respect; an enviable salary.

What was it all worth now? If those twelve years hadn’t been, if all her choices still lay before her, what would she do differently?

Everything. Anything to have him with her.

She met Buddy’s eyes. “You’d be surprised how much I’ve changed.” She lightened her words with a smile. “What about you? Besides being as devastatingly handsome as ever, still the most feared and respected lawman in the parish?”

“I don’t know about that,” he murmured. “Seems to me, these days that honor belongs to Matt.”

“West Feliciana Parish’s sheriff is retiring next year,” Cherry chimed in. “Matt’s planning to run for the job.” There was no mistaking the pride in her voice. “Those in the know expect him to win the election by a landslide.”

Buddy nodded, looking as pleased as punch. “My son, the parish’s top cop. Imagine that.”

“A regular crime-fighting family dynasty,” Avery murmured.

“Not for long.” Buddy settled into his easy chair. “Retirement’s right around the corner. Probably should have retired already. If I’d had a grandchild to spoil, I—”

“Dad,” Cherry warned, “don’t go there.”

“Three children,” he groused, “all disappointments. Friends of mine have a half-dozen of the little critters already. I don’t think that’s right.” He looked at Avery. “Do you?”

Avery held up her hands, laughing. “Oh, no, I’m not getting involved in this one.”

Cherry mouthed a “Thank you,” Buddy pouted and Avery changed the subject. “I can’t imagine you not being the chief of police. Cypress Springs won’t be the same.”

“Comes a time one generation needs to make room for the next. Much as I hate the thought, my time has come and gone.”

With a derisive snort, Cherry started toward the kitchen. “I’m having a glass of wine. Want one, Avery?”

“Love one.”

“Red or white?”

“Whatever you’re having.” Avery let out a long breath and leaned her head against the sofa back, tension easing from her. She closed her eyes. Images played on the backs of her eyelids, ones from her past: her, Matt and Hunter playing while their parents barbecued in the backyard. Buddy and Lilah snapping pictures as she and Matt headed off to the prom. The two families caroling at Christmastime.

Sweet memories. Comforting ones.

“Good to be back, isn’t it?” Buddy murmured as if reading her thoughts.

She opened her eyes and looked at him. “Despite everything, yes.” She glanced away a moment, then back. “I wish I’d come home sooner. After Mom … I should have stayed. If I had—”

The unfinished thought hung heavily between them anyway. If she had, maybe her dad would be alive today.

Cherry returned with the wine. She crossed to Avery; handed her a glass of the pale gold liquid. “What are your plans?”

“First order of business is a service for Dad. I called Danny Gallagher this afternoon. We’re meeting tomorrow after lunch.”

“How long are you staying?” Cherry sat on the other end of the couch, curling her legs under her.

“I took a leave of absence from the Post, because I just don’t know,” she answered honestly. “I haven’t a clue how long it will take to go through Dad’s things, get the house ready to sell.”

“Sorry I’m late.”

At Matt’s voice, Avery looked up. He stood in the doorway to the living room, head cocked as he gazed at her, expression amused. He’d exchanged his uniform for blue jeans and a soft chambray shirt. He held a bouquet of fresh flowers.

“Brought Mom some posies,” he said. “She in the kitchen?”

“You know Mom.” Cherry crossed to him and kissed his cheek. “Dad’s already complained about the dearth of grandchildren around here. Remind me to be late next time.”

Matt met Avery’s eyes and grinned. “Glad I missed it. Though I’ll no doubt catch the rerun later.”

Buddy scowled at his two children. “No grandbabies and no respect.” He looked toward the kitchen. “Lilah,” he bellowed, “where did we go wrong with these kids?”

Lilah poked her head out of the kitchen. “For heaven’s sake, Buddy, leave the children alone.” She turned her attention to her son. “Hello, Matt. Are those for the table?”

“Yes, ma’am.” He ambled across to her, kissed her cheek and handed her the flowers. “Something smells awfully good.”

“Come, help me with the roast.” She turned to her daughter. “Cherry, could you put these in a vase for me?”

Avery watched the exchange. She could have been a part of this family. Officially a part. Everyone had expected her and Matt to marry.

Buddy interrupted her thoughts. “Have you considered staying?” he asked. “This is your home, Avery. You belong here.”

She dragged her gaze back to his, uncertain how to answer. Yes, she had come home to take care of specific family business, but less specifically, she had come for answers. For peace of mind—not only about her father’s death, but about her own life.

Truth was, she had been drifting for a while now, neither happy nor unhappy. Vaguely dissatisfied but uncertain why.

“Do I, Buddy? Always felt like the one marching to a different drummer.”

“Your daddy thought so.”

Tears swamped her. “I miss him so much.”

“I know, baby girl.” A momentary, awkward silence fell between them. Buddy broke it first. “He never got over your mother’s death. The way she died. He loved her completely.”

She’d been behind the wheel when she suffered a stroke, on her way to meet her cousin who’d flown into New Orleans. For a week of girl time—shopping and dining and shows. She had careened across the highway, into a brick wall.

A sound from the doorway drew her gaze. Lilah stood there, expression stricken. Matt and Cherry stood behind her. “It was so … awful. She called me the night before she left. She hadn’t been feeling well, she said. She had run her symptoms by Phillip, had wondered if she shouldn’t cancel her trip. He had urged her to go. Nothing was wrong with her that a week away wouldn’t cure. I don’t think he ever forgave himself for that.”

“He thought he should have known,” Buddy murmured. “Thought that if he hadn’t been paying closer attention to his patients’ health than to his own wife’s, he could have saved her.”

Avery clasped her shaky hands together. “I didn’t know. I … he mentioned feeling responsible, but I—”

She had chosen to pacify him. To assure him none of it was his fault.

Then go on her merry way.

Matt moved around his mother and came to stand behind her chair. He laid a comforting hand on her shoulder. “It’s not your fault, Avery,” he said softly. “It’s not.”

She reached up and curled her fingers around his, grateful for the support. “Matt said Dad had been acting strangely. That he had withdrawn from everyone and everything. But still I … how could he have done what he did?”

“When I heard how he did it,” Cherry said quietly, “I wasn’t surprised. I think you can love someone so much you do something … unbelievable because of it. Something tragic.”

An uncomfortable silence settled over the group. Avery tried to speak but found she couldn’t for the knot of tears in her throat.

Buddy, bless him, took over. He turned to Lilah. “Dinner ready, sugar-sweet?”

“It is.” Lilah all but jumped at the opportunity to turn their attention to the mundane. “And getting cold.”

“Let’s get to it, then,” Buddy directed.

They made their way to the dining room and sat. Buddy said the blessing, then the procession of bowls and platters began, passed as they always had been at the Stevenses’ supper table from right to left.

Avery went through the motions. She ate, commented on the food, joined in story swapping. But her heart wasn’t in it. Nor was anyone else’s, that was obvious to her. As was how hard they were trying to make it like it used to be. How hard they were wanting to comfort with normalcy.

But how could anything be normal ever again? In years gone by, her parents had sat with her at this table. She, Matt and Hunter would have been clustered together, whispering or joking.

She missed Hunter, Avery realized. She felt the lack of his presence keenly.

Hunter had been the most intellectual of the group. Not the most intelligent, because both he and Matt had sailed through school, neither having to crack a book to maintain an A average, both scoring near-perfect marks on their SATs.

But Hunter had possessed a sharp, sarcastic wit. He’d been incapable of the silliness the rest of them had sometimes wallowed in. He had often been the voice of wry reason in whatever storm was brewing.

She hadn’t been surprised to hear he had become a successful lawyer. Between his keen mind and razor-sharp tongue, he’d no doubt consistently decimated the opposition.

She brought him up as Lilah served the pie. “Matt tells me that Hunter’s moved back to Cypress Springs. I’d hoped he would be here tonight.”

Silence fell around the table. Avery shifted her gaze from one face to the next. “I’m sorry, did I say something wrong?”

Buddy cleared his throat. “Of course not, baby girl. It’s just that Hunter’s had some troubles lately. Lost his partnership in the New Orleans law firm. Was nearly disbarred, from what I hear. Moved back here about ten months ago.”

“I don’t know why he bothered,” Matt added. “For all the time he spends with his family.”

Cherry frowned. “I wish he hadn’t come home. He only did it to hurt us.”

“Now, Cherry,” Buddy murmured, “you don’t know that.”

“The hell I don’t. If he was any kind of brother, any kind of son, he would be here for us. Instead, he—”

Lilah launched to her feet. Avery saw she was near tears. “I’ll get the coffee.”

“I’ll help.” Cherry tossed her napkin on the table and got to her feet, expression disgusted. She looked at Avery. “Tell you the truth, all Hunter’s ever done is break our hearts.”

CHAPTER 3

Talk of Hunter drained the joy from the gathering, and the remainder of the evening passed at a snail’s pace. Lilah’s smile looked artificial; Cherry’s mood darkened with each passing moment and Buddy’s jubilance bordered on manic.

Finally, pie consumed, coffee cups drained, Avery said her thanks and made her excuses. Cherry and Lilah said their goodbyes in the dining room; Buddy accompanied her and Matt to the door.

Buddy hugged her. “You broke all our hearts when you left. But no one’s more than mine. I’d had mine set on you being my daughter.”

Avery returned his embrace. “I love you, too, Buddy.”

Matt walked her to her car. “Pretty night,” she murmured, lifting her face to the night sky. “So many stars. I’d forgotten how many.”

“I enjoyed tonight, Avery. It was like old times.”

Avery met his eyes; her pulse fluttered.

“I’ve missed you,” he said. “I’m glad you’re back.”

She swallowed hard, acknowledging that she’d missed him, too. Or more accurately, that she’d missed standing with him this way, in his folks’ driveway, under a star-sprinkled sky. Had missed the familiarity of it. The sense of belonging.

Matt put words to her thoughts. “Why’d you leave, Avery? My dad was right, you know. You belong here. You’re one of us.”

“Why didn’t you go with me?” she countered. “I asked. Begged, if I remember correctly.”

Matt lifted a hand as if to touch her, then dropped it. “You always wanted something else, something more than Cypress Springs could offer. Something more than I could offer. I never understood it. But I had to accept it.”

She shifted her gaze slightly, uncomfortable with the truth. That he could speak it so plainly. She changed the direction of their conversation. “Your dad and Cherry said you’re the front-runner in next year’s election for parish sheriff. I’m not surprised. You always said you were destined for great things.”

“But our definitions of great things always differed, didn’t they, Avery?”

“That’s not fair, Matt.”

“Fair or not, it’s true.” He paused. “You broke my heart.”

She held his gaze. “You broke mine, too.”

“Then we’re even, aren’t we? A broken heart apiece.”

She winced at the bitter edge in his voice. “Matt, it … wasn’t you. It was me. I never felt—”

She had been about to say how she had never felt she belonged in Cypress Springs. That once she’d become a teenager, she had always felt slightly out of step, different in subtle but monumental ways from the other girls she knew.

Those feelings seemed silly now. The thoughts of a self-absorbed young girl.

“What about now, Avery?” he asked. “What do you want now? What do you need?”

Discomfited by the intensity of his gaze, she looked away. “I don’t know. I don’t want to return to where I was, I’m certain of that. And I don’t mean the geographical location.”

“Sounds like you have some thinking to do.”

A giant understatement. She turned to the Blazer, unlocked the door, then faced him once more. “I should go. I’m asleep on my feet and tomorrow’s going to be difficult.”

“You could stay here, you know. Mom and Dad have plenty of room. They’d love to have you.”

A part of her longed to jump at the offer. The idea of sleeping in her parents’ house now, after her father … she didn’t think she would sleep a wink.

But taking the easy way would be taking the coward’s way. She had to face her father’s suicide. She’d begin tonight, by sleeping in her childhood home.

He reached around her and opened her car door. “Still fiercely independent, I see. Still stubborn as a mule.”

She slid behind the wheel, started the vehicle, then looked back up at him “Some would consider those qualities an asset.”

“Sure they would. In mules.” He bent his face to hers. “If you need anything, call me.”

“I will. Thanks.” He slammed the door. She backed the Blazer down the steep driveway, then headed out of the subdivision, pointing the vehicle toward the old downtown neighborhood where she had grown up.

Avery shook her head, remembering how she had begged her parents to follow the Stevenses to Spring Water, the then new subdivision where Matt and his family had bought a house. She had been enamored with the sprawling ranch homes and neighborhood club facilities: pool, tennis court and clubhouse for parties.

What had then looked so new and cool to her, she saw now as cheaply built, cookie-cutter homes on small plots of ground that had been cleared to make room for as many houses per acre as possible.

Luckily, her parents had refused to move from their location within walking distance of the square, downtown and her father’s office. Solidly built in the 1920s, their house boasted high ceilings, cypress millwork and the kind of charm available only at a premium today. The neighborhood, too, was vintage—a wide, tree-lined boulevard lit by gas lamps, each home set back on large, shady lots. Unlike many cities whose downtown neighborhoods had fallen victim to the urban decay caused by crime and white flight, Cypress Springs’s inner-city neighborhood remained as well maintained and safe as when originally built.

Despite the fact that most of Louisiana was flat, West Feliciana Parish was home to gently rolling hills. Cypress Springs nestled amongst those hills—the historic river town of St. Francisville, with its beautiful antebellum homes, lay twenty minutes southwest, Baton Rouge, forty-five minutes south and the New Orleans’s French Quarter a mere two hours forty-five minutes southeast.

Besides being a good place to raise a family, Cypress Springs had no claim to fame. A small Southern town that relied on agriculture, mostly cattle and light industry, it was too far from the beaten path to ever grow into more.

The city fathers liked it that way, Avery knew. She had grown up listening to her dad, Buddy and their friends talk about keeping industry and all her ills out. About keeping Cypress Springs clean. She remembered the furor caused when Charlie Weiner had sold his farm to the Old Dixie Foods corporation and then the company’s decision to build a canning factory on the site.

Avery made her way down the deserted streets. Although not even ten o’clock, the town had already rolled up its sidewalks for the night. She shook her head. Nothing could be more different from the places she had called home for the past twelve years—places where a traffic jam could occur almost anytime during a twenty-four-hour period; where walking alone at night was to take your life in your hands; places where people lived on top of each other but never acknowledged the other’s existence.

As beautiful and green a city as Washington, D.C., was, it couldn’t compare to the lush beauty of West Feliciana Parish. The heat and humidity provided the perfect environment for all manner of vegetation. Azaleas. Gardenias. Sweet olive. Camellias. Palmettos. Live oaks, their massive gnarled branches so heavy they dipped to the ground, hundred-year-old magnolia trees that in May would hold so many of the large white blossoms the air would be redolent of their sweet, lemony scent.

Once upon a time she had thought this place ugly. No, that wasn’t quite fair, she admitted. Shabby and painfully small town.

Why hadn’t she seen it then as she did now?

Avery turned onto her street, then a moment later into her parents’ driveway. She parked at the edge of the walk and climbed out, locking the vehicle out of habit not necessity. Her thoughts drifted to the events of the evening, particularly to those final moments with Matt.

What did she want now? she wondered. Where did she belong?

The porch swing creaked. A figure separated from the silhouette of the overgrown sweet olive at the end of the porch. Her steps faltered.

“Hello, Avery.”

Hunter, she realized, bringing a hand to her chest. She let out a shaky breath. “I’ve lived in the city too long. You scared the hell out of me.”

“I have that effect on people.”

Although she smiled, she could see why that might be true. Half his face lay in shadow, the other half in the light from the porch fixture. His features looked hard in the weak light, his face craggy, the lines around his mouth and eyes deeply etched. A few days’ accumulation of beard darkened his jaw.

She would have crossed the street to avoid him in D.C.

How could the two brothers have grown so physically dissimilar? she wondered. Growing up, though fraternal not identical twins, the resemblance between them had been uncanny. She would never have thought they could be other than near mirror images of one another.

“I’d heard you were back,” he said. “Obviously.”

“News travels fast around here.”

“This is a small town. They’ve got to have something to talk about.”

He had changed in a way that had less to do with the passage of years than with the accumulated events of those years. The school of hard knocks, she thought. The great equalizer.

“And I’m one of their own,” she said.

“It’s true, then? You’re back to stay?”

“I didn’t say that.”

“That’s the buzz. I thought it was wrong.” He shrugged. “But you never know.”

“Meaning what?” she asked, folding her arms across her chest.

“Am I making you uncomfortable?”

“No, of course not.” Annoyed with herself, she dropped her arms. “I had dinner with your parents tonight.”

“And Matt. Heard that, too.”

“I thought you might have been there.”

“So they told you I was living in Cypress Springs?”

“Matt did.”

“And did he tell you why?”

“Only that you’d had some troubles.”

“Nice euphemism.” He swept his gaze over the facade of her parents’ house. “Sorry about your dad. He was a great man.”

“I think so, too.” She jiggled her car keys, suddenly on edge, anxious to be inside.

“Aren’t you going to ask me?”

“What?”

“If I talked to him before he died.”

The question off-balanced her. “What do you mean?”

“It seemed a pretty straightforward question to me.”

“Okay. Did you?”

“Yes. He was worried about you.”

“About me?” She frowned. “Why?”

“Because your mother died before the two of you worked out your issues.”

Issues, she thought. Is that how one summed up a lifetime of hurt feelings, a lifetime of longing for her mother’s unconditional love and approval and being disappointed time and again? Her head filled with a litany of advice her mother had offered her over the years.

“Avery, little girls don’t climb trees and build forts or play cowboys and Indians with boys. They wear bows and dresses with ruffles, not blue-jean cutoffs and T-shirts. Good girls make ladylike choices. They don’t run off to the city to become newspapermen. They don’t throw away a good man to chase a dream.”

“He thought you might be sad about that,” Hunter continued. “She was. He hated that she died without your making peace.”

“He said that?” she managed to get out, voice tight.

He nodded and she looked away, memory flooding with the words she had flung at her mother just before she had left for college.

“Drop the loving concern, Mother! You’ve never approved of me or my choices. I’ve never been the daughter you wanted. Why don’t you just admit it?”

Her mother hadn’t admitted it and Avery had headed off to college with the accusation between them. They had never spoken of it again, though it had been a wedge between them forever more.

“He figured that’s why you hardly ever came home.” Hunter shrugged. “Interesting, you couldn’t come to terms with your mother’s life, he her death.”

She jumped on the last. “What does that mean, he couldn’t come to terms with her death?”

“I would think it’s obvious, Avery. It’s called grieving.”

He was toying with her, she realized. It pissed her off. “And when did all these conversations take place?”

Hunter paused. “We had many conversations, he and I.”

The past two days, her shock and grief, the grueling hours of travel, the onslaught of so much that was both foreign and familiar, came crashing down on her. “I don’t have the energy to deal with your shit, even if I wanted to. If you decide you want to be a decent human being, look me up.”

One corner of his mouth lifted in a sardonic smile. “I didn’t answer your question before, the one about my opinion of the local buzz. Personally, I figured you’d pop your old man in a box and go. Fast as you could.”

She took a step back, stung. Shocked that he would say that to her. That he would be so cruel. After the closeness they had shared. She pushed past him, unlocked her front door and stepped inside. She caught a glimpse of his face, of the stark pain that etched his features as she slammed the door.

Hunter Stevens was a man pursued by demons. To hell with his, she thought, twisting the dead-bolt lock. She had her own to deal with.

CHAPTER 4

Hunter gazed at the row of unopened bottles: beer, wine, whisky, vodka. All sins from his past. Each a nail in the coffin of his life.

He kept them around to prove that he could. Such a strategy went counter to traditional AA teaching, but he was a masochistic son of a bitch.

Hunter thought of Avery and anger rose up in him in a white-hot, suffocating wave. Once upon a time they’d been the best of friends: him, Matt and Avery. Before everything had begun spinning crazily out of control. Before his life had turned to shit.

He pictured her sitting next to Matt at his family’s dinner table. All of them laughing, swapping memories. Reveling in the good old days.

What part had he played in those memories? Had they shared stories that hadn’t included him? Or had they simply plucked him out as if he had never existed?

Shut out again. Always the one on the outside, looking in. The one who didn’t belong.

“What’s wrong with you, Hunter? What went wrong with you?”

Good question, he thought, gazing at the bottles, squeezing his fists against the urge that swelled inside him. The urge to open a bottle and get stinking, fall-down drunk.

He’d been down that path; he knew the only place it would lead him was straight to hell.

A hell of his own making. One populated by children screaming in terror. One in which he was helpless to stop the inevitable. Helpless to do more than look on in horror and self-loathing. In despair.

Hunter swung away from the bottles. He sucked in a deep breath and moved deliberately away from the kitchen and toward the makeshift desk he had set up in the corner of his small living room. On the desk sat a computer, monitor glowing in the dimly lit room, fan humming softly. Beside it the pages of a novel. His novel. A story about a lawyer’s spiral to the depths.

If only he knew the story’s end. Some days, he thought his protagonist would manage to claw his way up from those depths. Other days, hopelessness held him so tightly in its grip he couldn’t breathe let alone imagine a happy ending.

He pulled out the chair and sat, intent on channeling his energy and anger into his novel. Instead, he found his thoughts turning to Avery once more.

What caused a man to douse himself with a flammable substance and strike a match?

He knew. He understood.

He had been there, too.

The blinking cursor drew his attention. He focused on the words he had written:

Jack fought the forces that threatened to devour him. To his right lay the laws of man, to his left the greatness of God. One wrong step and he would be lost.

Lost. And found. He had come home to set things right. To start over. He had already begun.

And now, here was Avery.

All together again, he thought. He, Matt and Avery. The same as when his life had begun to implode. How would this affect his plans? The timetable of events he had carefully constructed?

It wouldn’t, he decided. Things would be set right. His life would be set right. No matter how much it hurt.

CHAPTER 5

Avery bolted upright in bed, heart pounding, her father’s name a scream on her lips. She darted her gaze to the bedroom door, for a split second a kid again, expecting her parents to charge through, all concerned hugs and comforting arms.

They didn’t, of course, and she sagged back against the headboard. She hadn’t slept well, no surprise there. She’d tossed and turned, each creak and moan of the old house unfamiliar and jarring. She had been up a half dozen times. Checking the doors. Peering out the windows. Pacing the floor.

In truth, she suspected it hadn’t been the noises that had kept her awake. It had been the quiet. The reason for the quiet.

Finally, she’d taken the couple of Tylenol PM caplets she’d dug out of her travel bag. Sleep had come.

But not rest. For sleep had brought nightmares. In them, she had been enfolded in a womb, warm and contented. Protected. Suddenly, she had been torn from her safe haven and thrust into a bright, white place. The light had burned. She had been naked. And cold.

In the next instant flames had engulfed her.

And she had awakened, calling out her father’s name.

Not too tough figuring that one out.

Avery glanced at the bedside clock. Just after 9:00 a.m., she noted. Throwing back the blanket, she climbed out of bed. The temperature had dropped during the night and the house was cold. Shivering, she crossed to her suitcase, rummaged through it for a pair of leggings and a sweatshirt. She slipped them on, not bothering to take off her sleep shirt.

That done, she headed to the kitchen, making a quick side trip out front for the newspaper. It wasn’t until she was staring at the naked driveway that two things occurred to her: the first was that Cypress Springs’s only newspaper, the Gazette, was a biweekly, published each Wednesday and Saturday, and second, that Sal Mandina, the Gazette’s owner and editor-in-chief had surely halted her father’s subscription. There would be no uncollected papers piling up on a Cypress Springs stoop.

No newspaper? The very idea made her twitch.

With a shake of her head, she stepped inside, relocked the door and headed to the kitchen. She would pick up the New Orleans Times-Picayune or The Advocate from Baton Rouge when she went into town this morning.

That trip might come sooner than planned, Avery realized moments later, standing at the refrigerator. Yesterday she hadn’t thought to check the kitchen for provisions. She wished she had.

No bread, milk or eggs. No coffee.

Not good.

Avery dragged her fingers through her short hair. After the huge meal she’d consumed the night before, she could probably forgo breakfast. Maybe. But she couldn’t face this morning without coffee.

A walk downtown, it seemed, would be the first order of the day.

After changing, brushing her teeth and washing her face, she found her Reeboks, slipped them on then headed out the front door.

And ran smack into Cherry. The other woman smiled brightly. “Morning, Avery. And here I was afraid I was going to wake you.”

“No such luck.” Avery eyed the picnic basket tucked against Cherry’s side. “I was just heading to the grocery for a newspaper and some coffee. You wouldn’t happen to have either of those, would you?”

“A thermos of French roast. No newspaper, though. Sorry.”

“You’re a lifesaver. Come on in.”

Cherry stepped inside. “I remembered that your dad didn’t drink coffee. Figured you’d need it this morning, strong.”

Her mother had been a coffee drinker. But not her dad. Cherry had remembered that. But she hadn’t. What was wrong with her?

“Figured, too, that you hadn’t had time to get to the market.” She held up the basket. “Mom’s homemade biscuits and peach jam.”

Just the thought had Avery’s mouth watering. “Do you have any idea how long it’s been since I had a real biscuit?”

“Since your last visit, I suspect,” Cherry answered, following Avery. They reached the kitchen and she set the basket on the counter. “Yankees flat can’t make a decent biscuit. There, I’ve said it.”

Avery laughed. She supposed the other woman was right. Learning how to make things like the perfect baking powder biscuit was a rite of passage for Southern girls.

And like many of those womanly rites of passage, she had failed miserably at it.

Cherry had come prepared: from the basket she took two blue-and-white-checked place mats, matching napkins, flatware, a miniature vase and carefully wrapped yellow rose. She filled the vase with water and dropped in the flower. “There,” she said. “A proper breakfast table.”

Avery poured the coffees and the two women took a seat at the table. Curling her fingers around the warm mug, Avery made a sound of appreciation as she sipped the hot liquid.

“Bad night?” Cherry asked sympathetically, bringing her own cup to her lips.

“The worst. Couldn’t sleep. Then when I did, had nightmares.”

“That’s to be expected, I imagine. Considering.”

Considering. Avery looked away. She cleared her throat. “This was so sweet of you.”

“My pleasure.” Cherry smoothed the napkin in her lap. “I meant what I said last night, I’ve missed you. We all have.” She met Avery’s eyes. “You’re one of us, you know. Always will be.”

“Are you trying to tell me something, Cherry?” Avery asked, smiling. “Like, you can take the girl out of the small town, but you can’t take the small town out of the girl?”

“Something like that.” She returned Avery’s smile; leaned toward her. “But you know what? There’s nothing wrong with that, in my humble, country opinion. So there.”

Avery laughed and helped herself to one of the biscuits. She broke off a piece. It was moist, dense and still warm. She spread on jam, popped it in her mouth and made a sound of pure contentment. Too many meals like this and the one last night, and she wouldn’t be able to snap her blue jeans.

She broke off another piece. “So, what’s going on with you, Cherry? Didn’t you graduate from Nicholls State a couple years ago?”

“Harvard on the bayou to us grads. And it was last year. Got a degree in nutrition. Not much call for nutritionists in Cypress Springs,” she finished with a shrug. “I guess I didn’t think that through.”

“You might try Baton Rouge or—”

“I’m not leaving Cypress Springs.”

“But you’d be close enough to—”

“No,” she said flatly. “This is my home.”

Awkward silence fell between them. Avery broke it first. “So what are you doing now?”

“I help Peg out down at the Azalea Café. And I sit on the boards of a couple charities. Teach Sunday school. Make Mom’s life easier whenever I can.”

“Has she been ill?”

She hesitated, then smiled. “Not at all. It’s just … she’s getting older. I don’t like to see her working herself to a frazzle.”

Avery took another sip of her coffee. “You live at home?”

“Mmm.” She set down her cup. “It seemed silly not to. They have so much room.” She paused a moment. “Mama and I talked about opening our own catering business. Not party or special-events catering, but one of those caterers who specialize in nutritious meals for busy families. We were going to call it Gourmet-To-Go or Gourmet Express.”

“I’ve read a number of articles about those caterers. Apparently, it’s the new big thing. I think you two would be great at that.”

Cherry smiled, expression pleased. “You really think so?”

“With the way you both cook? Are you kidding? I’d be your first customer.”

Her smile faltered. “We couldn’t seem to pull it together.

Besides, I’m not like you, Avery. I don’t want some big, fancy career. I want to be a wife and mother. It’s all I ever wanted.”

Avery wished she could be as certain of what she wanted. Of what would make her happy. Once upon a time she had been. Once upon a time, it seemed, she had known everything.

Avery leaned toward the other woman. “So, who is he? There must be a guy in the picture. Someone special.”

The pleasure faded from Cherry’s face. “There was. He—Do you remember Karl Wright?”

Avery nodded. “I remember him well. He and Matt were good friends.”

“Best friends,” Cherry corrected. “After Matt and Hunter … fell out. Anyway, we had something special … at least I thought we did. It didn’t work out.”

Avery reached across the table and squeezed her hand. “I’m sorry.”

“He just up and … left. Went to California. We’d begun talking marriage and—”

She let out a sharp breath and stood. She crossed to the window and for a long moment simply stared out at the bright morning. Finally she glanced back at Avery. “I was pushing. Too hard, obviously. He called Matt and said goodbye. But not me.”

“I’m really sorry, Cherry.”

She continued as if Avery hadn’t spoken. “Matt urged him to call me. Talk it out. Compromise, but … “ Her voice trailed helplessly off.

“But he didn’t.”

“No. He’d talked about moving to California. I always resisted. I didn’t want to leave my family. Or Cypress Springs. Now I wish … “

Her voice trailed off again. Avery stood and crossed to her. She laid a hand on her shoulder. “Someone else will come along, Cherry. The right one.”

Cherry covered her hand. She met Avery’s eyes, hers filled with tears. “In this town? Do you know how few eligible bachelors there are here? How few guys my age? They all leave. I wish I wanted a career, like you. Because I could do that on my own. But what I want more than anything takes two. It’s just not fai—”

Her voice cracked. She swallowed hard; cleared her throat. “I sound the bitter old spinster I am.”

Avery smiled at that. “You’re twenty-four, Cherry. Hardly a spinster.”

“But that’s not the way I … It hurts, Avery.”

“I know.” Avery thought of what Cherry had said the night before, about loving someone to the point of tragedy. In light of this conversation, her comment concerned Avery. She told her so.

Cherry wiped her eyes. “Don’t worry, I’m not going to do anything crazy. Besides,” she added, visibly brightening, “maybe Karl will come back? You did.”

Avery didn’t have the heart to correct her. To tell her she wasn’t certain what her future held. “Have you spoken with him since he left?”

Fresh tears flooded Cherry’s eyes. Avery wished she could take the question back. “His dad’s gotten a few letters. He’s over in Baton Rouge, at a home there. I go see him once a week.”

“And Matt?”

“They spoke once. And fought. Matt chewed him out pretty good. For the way he treated me. He hasn’t heard from him since.”

Avery could bet he had chewed him out. Matt had always returned Cherry’s hero worship with a kind of fierce protectiveness.

“He’s missed you, you know.”

Avery met Cherry’s gaze, surprised. “Excuse me?”

“Matt. He never stopped hoping you’d come back to him.”

Avery shook her head, startled by the rush of emotion she felt at Cherry’s words. “A lot of time’s passed, Cherry. What we had was wonderful, but we were very young. I’m sure there have been other women since—”

“No. He’s never loved anyone but you. No one ever measured up.”

Avery didn’t know what to say. She told Cherry so.

The younger woman’s expression altered slightly. “It’s still there between you two. I saw it last night. So did Mom and Dad.”

When she didn’t reply, Cherry narrowed her eyes. “What are you so afraid of, Avery?”

She started to argue that she wasn’t, then bit the words back. “A lot of time’s passed. Who knows if Matt and I even have anything in common anymore.”

“You do.” Cherry caught her hand. “Some things never change. And some people are meant to be together.”

“If that’s so,” Avery said, forcing lightness into her tone, “we’ll know.”

Instead of releasing her hand, Cherry tightened her grip. “I can’t allow you to hurt him again. Do you understand?”

Uncomfortable, Avery tugged on her hand. “I have no plans of hurting your brother, believe me.”

“I’m sure you mean that, but if you’re not serious, just stay away, Avery. Just … stay … away.”

“Let go of my hand, Cherry. You’re hurting me.”

She released Avery’s hand, looking embarrassed. “Sorry. I get a little intense when it comes to my brothers.”

Without waiting for Avery to respond, she made a show of glancing at her watch, exclaiming over the time and how she would be late for a meeting at the Women’s Guild. She quickly packed up the picnic basket, insisting on leaving the thermos of coffee and remaining biscuits for Avery.

“Just bring the thermos by the house,” she said, hurrying toward the door.

It wasn’t until Cherry had backed her Mustang down the driveway and disappeared from sight that Avery realized how unsettled she was by the way their conversation had turned from friendly to adversarial. How unnerved by the woman’s threatening tone and the way she had seemed to transform, becoming someone Avery hadn’t recognized.

Avery shut the door, working to shake off the uncomfortable sensations. Cherry had always looked up to Matt. Even as a squirt, she had been fiercely protective of him. Plus, still smarting from her own broken heart made her hypersensitive to the idea of her brother’s being broken.

No, Avery realized. Cherry had referred to her brothers, plural. She got a little intense when it came to her brothers.

Odd, Avery thought. Especially in light of the things she had said about Hunter the night before. If Cherry felt as strongly about Hunter as she did about Matt, perhaps she’d had more interaction with Hunter than she’d claimed. And perhaps her anger was more show than reality.

But why hide the truth? Why make her feelings out to be different than they were?

Avery shook her head. Always looking for the story, she thought. Always looking for the angle, the hidden motive, the elusive piece of the puzzle, the one that broke the story wide open.

Geez, Avery. Give it a rest. Stop worrying about other people’s issues and get busy on your own.

She certainly had enough of them, she acknowledged, shifting her gaze to the stairs. After all, if she got herself wrapped up in others’ lives and problems, she didn’t have to face her own. If she was busy analyzing other people’s lives, she wouldn’t have time to analyze her own.

She wouldn’t have to face her father’s suicide. Or her part in it.

Avery glanced up the stairway to the second floor. She visualized climbing it. Reaching the top. Turning right. Walking to the end of the hall. Her parents’ bedroom door was closed. She had noticed that the night before. Growing up, it had always been open. It being shut felt wrong, final.

Do it, Avery. Face it.

Squaring her shoulders, she started toward the stairs, climbed them slowly, resolutely. She propelled herself forward with sheer determination.

She reached her parents’ bedroom door and stopped. Taking a deep breath, she reached out, grasped the knob and twisted. The door eased open. The bed, she saw, was unmade. The top of her mother’s dressing table was bare. Avery remembered it adorned with an assortment of bottles, jars and tubes, with her mother’s hairbrush and comb, with a small velveteen box where she had kept her favorite pieces of jewelry.

It looked so naked. So empty.

She moved her gaze. Her father had removed all traces of his wife. With them had gone the feeling of warmth, of being a family.

Avery pressed her lips together, realizing how it must have hurt, removing her things. Facing this empty room night after night. She’d asked him if he needed help. She had offered to come and help him clean out her mother’s things. Looking back, she wondered if he had sensed how halfhearted that offer had been. If he had sensed how much she hadn’t wanted to come home.

“I’ve got it taken care of, sweetheart. Don’t you worry about a thing.”

So, she hadn’t. That hurt. It made her feel small and selfish. She should have been here. Avery shifted her gaze to the double dresser. Would her mother’s side be empty? Had he been able to do what she was attempting to do now?

She hung back a moment more, then forced herself through the doorway, into the bedroom. There she stopped, took a deep breath. The room smelled like him, she thought. Like the spicy aftershave he had always favored. She remembered being a little girl, snuggled on his lap, and pressing her face into his sweater. And being inundated with that smell—and the knowledge that she was loved.

The womb from her nightmare. Warm, content and protected.

Sometimes, while snuggled there, he had rubbed his stubbly cheek against hers. She would squeal and squirm—then beg for more when he stopped.

Whisker kisses, Daddy. More whisker kisses.

She shook her head, working to dispel the memory. To clear her mind. Remembering would make this more difficult than it already was. She crossed to the closet, opened it. Few garments hung there. Two suits, three sports coats. A half-dozen dress shirts. Knit golf shirts. A tie and belt rack graced the back of the door; a shoe rack the floor. She stood on tiptoe to take inventory of the shelf above. Two hats—summer and winter. A cardboard storage box, taped shut.

Her mom’s clothes were gone.

Avery removed the box, set it on the floor, then turned and crossed to the dresser. On the dresser top sat her dad’s coin tray. On it rested his wedding ring. And her mother’s. Side by side.

The implications of that swept over her in a breath-stealing wave. He had wanted them to be together. He had placed his band beside hers before he—

Blinded by tears, Avery swung away from the image of those two gold bands. She scooped up the cardboard box and hurried from the room. She made the stairs, ran down them. She reached the foyer, dropped the box and darted to the front door. She yanked it open and stepped out into the fresh air.

Avery breathed deeply through her nose, using the pull of oxygen to steady herself. She had known this wouldn’t be easy.

But she hadn’t realized it would be so hard. Or hurt so much.