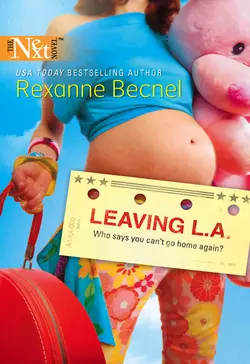

Leaving L.a.

Rexanne Becnel

There's a first time for everything…as thirty-nine-year-old Zoe Vidrine learned the hard way. She was pregnant! Now the aging rock 'n' roller had to change her tune fast. Her plan: leave behind the temptations of L.A.–and her famous hard-partying ex who had got her into this mess–and return to her family's Louisiana homestead to regroup.It had been twenty years, and the Day Glo hippie haven where Zoe had spent an unhappy childhood was gone, remodeled in the signature pastels of her prim sister Alice. Alice's aesthetic sense was hard enough to swallow, but her holier-than-thou attitude set the stage for a showdown. Still, as the sisters gradually came to terms with their shared past, would there be a meeting of the minds? Talk about firsts…USA TODAY bestselling author Rexanne Becnel has created all twenty-two of her novels in coffeehouses, writing longhand. Thanks to the stimulating effects of way too many cups of coffee, she's found a grateful audience of both readers and critics.

Praise for Rexanne Becnel’s NEXT novels

“Humor, smart women, adventure, and danger all add up to a book you can’t put down…. Constant surprises and characters that will win your heart.”

—Romantic Times BOOKclub on The Payback Club

“Becnel deftly captures the way actual women think …Brisk and entertaining, with a welcome focus on middle-aged sexuality, this tidy tale proves that Becnel is just as much at home writing high-quality contemporary fiction as penning the historical fiction for which she’s known.”

—Publishers Weekly on Old Boyfriends

“Rexanne Becnel skillfully weaves multiple storylines with lively characters and unexpected plot twists in an emotionally satisfying book.”

—Romantic Times BOOKclub on Old Boyfriends

And other praise for Rexanne Becnel

“Ms. Becnel creates the most intriguing characters.”

—Literary Times on The Bride of Rosecliffe

“Becnel skillfully blends romance and adventure with a deft hand.”

—Publishers Weekly on When Lightning Strikes

“Rexanne’s stories stay with the reader long after the final page is turned.”

—Literary Times on Heart of the Storm

Rexanne Becnel

Rexanne Becnel, the author of twenty-one novels and two novellas, swears she could not be a writer if it weren’t for New Orleans’s many coffeehouses. She does all her work longhand, with a mug of coffee at her side. She is a charter member of the Southern Louisiana Chapter of Romance Writers of America, and founded the New Orleans Popular Fiction Conference.

Rexanne’s novels regularly appear on bestseller lists such as those of USA TODAY, Amazon.com, Waldenbooks, Ingram and Barnes & Noble. She has been nominated for and received awards from Romantic Times BOOKclub, Waldenbooks, The Holt Committee, the Atlanta Journal/ Atlanta Constitution and the National Readers Choice Awards.

Leaving L.A.

Rexanne Becnel

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Dear Reader,

I enjoyed writing Leaving L.A. more than any book I’ve ever done before. I think it was that I loved my heroine so much. She was fun and sassy, and troubled, too. But she was working hard to improve her life.

As in my previous titles, Leaving L.A. is set in southern Louisiana. I was almost finished with the book when Katrina hit New Orleans, where I live. My family and I spent a week in our house surrounded by water, then another two weeks away, before returning to start rebuilding our lives. It has been, shall we say, “interesting.” We lost a lot, but we know so many people who lost everything, including loved ones, that I actually feel blessed.

Leaving L.A. is set in a Louisiana pre-Katrina. My current work-in-progress deals with Katrina, both during and after. It’s been an emotional roller coaster, but it has also been cathartic.

Many thanks to all of you who have worried about us, volunteered to help us, or donated money to the many charities set up to aid us. A special thanks to the first responders, who worked so hard and often put their lives on the line. There will never be enough thanks.

I hope you enjoy my latest efforts,

Rexanne

For the Pizzolato family of Baton Rouge, who provided us safe harbor after Hurricane Katrina, and to Joanna Wurtele who got us there.

Also to David, Rosemary, Brian, Valerie, Chuck and Karen, who weathered the storm with me, and to Katya and Mike, who kept it together across town.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 (#u183113f0-b0f3-5b5b-aa40-f970e672bb0a)

CHAPTER 2 (#u4dbdc40b-fefe-58a3-a333-de4169ef99ae)

CHAPTER 3 (#udf1f05f4-71e3-563f-ad0d-7177f56e9489)

CHAPTER 4 (#uef7995b8-bba6-54ff-b024-4a4bc230eb1f)

CHAPTER 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1

I come from a long line of motherless daughters. I used to think of us as fatherless: my mother, my older half sister, me. But the truth is that the worst damage to us came from being essentially motherless.

That’s the conclusion I reached after six days, thirty cups of pure caffeine and two thousand miles of driving back home. Of course all that philosophical crap leached out of my head the minute I crossed the Louisiana state line. That’s when I started obsessing about what I would wear to my big reunion with my sister. I’m not proud to admit that I changed clothes three times in the last one hundred miles of my trek. The first time in a Burger King in Port Allen; the second time in a Shell station just east of Baton Rouge; and the third time on a dirt road beside a cow pasture just off Highway 1082.

Okay, I was nervous. How do you dress when you’re coming home for the first time in twenty-three years and you’re pretty sure your only sister is going to slam the door in your face—assuming she even recognizes you?

I settled on a pair of skin-tight leopard-print capris, a black Thomasina spaghetti-strap top with a built-in push-up bra, a pair of Rainbow stilettos and a black dog-collar choker with pyramid studs all around. My own personal power look: heavy metal, hot mama who’ll kick your ass if you get in my way.

But as soon as I turned into the driveway that led up to the farmhouse my grandfather had built over eighty years ago, I knew it was all wrong. I should have stuck with the jeans and the lime-green tank top.

I screeched to a halt and reached into the back seat where my rejected outfits were flung over my four suitcases, five boxes of books and records, and three giant plastic containers of photos, notebooks and dog food.

“This is the last change,” I muttered to Tripod, who just stared at me like I was a lunatic—which maybe I am. But who wants a dog passing judgment on you?

I glowered at him as I shimmied out of the spandex capris. They were getting kind of tight. Surely I wasn’t already gaining weight?

I was standing barefoot beside my open car door with my jeans almost zipped when my cranky three-legged mutt decided he’d had enough. Up to now I’d had to lift him into and out of the high seat of my ancient Jeep. That missing foreleg makes it hard for him to leap up and down. But apparently he’d been playing the sympathy card the whole two thousand miles of I-10 east because, as soon as I turned my back, he jumped down through the driver’s door and took off up the rutted shell driveway, baying like he was a Catahoula hound who’d just treed his first raccoon.

“Idiot dog,” I muttered as I snapped the fly of my jeans. The day I adopted him he’d just lost his leg in a fight with a Hummer on an up ramp to I-405 in Los Angeles. Not a genius among canines, and an urban mutt, to boot. The only wildlife he’d ever seen were the squirrels that raided the bird feeder I’d hung in the courtyard of my ex-boyfriend G.G.’s Palm Springs villa.

But here he was, lumbering down a rural Louisiana lane, for all intents and purposes pounding his hairy doggy chest and declaring this as his territory.

I paused and stared after him. Maybe he was on to something. Straightening up, I took a few experimental thumps on my own chest. “Watch out, world—especially you, Alice. Zoe Vidrine is back in town, and this time I’m not leaving with just a backpack and three changes of clothes. This time I’m not going until I get what’s rightfully mine.”

Then before I could change my mind about my clothes one more time, I slid into the driver’s seat, shoved Jenny into first gear, and tore down the Vidrine driveway, under the Vidrine Farm sign, and on to the Vidrine family homestead.

It was the same house. That’s what I told myself when I steered past a large curve of azaleas in full bloom. In a kind of fog I pressed the brake and eased to a stop at the front edge of the sunny lawn. It was the same house with the same deep porch and the same elaborate double chimney. My great-grandfather had been a mason before he turned to farming, and the chimney he’d built on his house would have fit on a New Orleans mansion.

I was in the right yard and this was the right house. But nothing else about it looked the same. Instead of peeling white paint interrupted with gashes of DayGlo-red peace signs and vivid green zodiac emblems spray painted in odd, impulsive places, the walls were a soft, serene yellow. The trim was a crisp white, and shiny, dark green shutters accented the windows on both floors. A pair of lush, trailing ferns flanked the wide front steps, moving languidly in the gentle spring breeze.

The day I’d finally fled my miserable childhood, there had been no steps at all, only a rickety pile of concrete blocks.

Now a white wicker porch swing hung on the left side of the porch, and three white, wooden rockers sat to the right.

It was the home of my childhood dreams, of all my desperate, adolescent yearnings. Nothing like the place I’d actually grown-up in.

I shuddered as my long-repressed anger and hurt boiled to the surface. How dare Alice try to gloss over the ugliness of our childhoods! How dare she slap paint down and throw a few plants into the ground and pretend everything was just fine and dandy in the Vidrine household!

Then again, my Goody Two-shoes sister had always looked the other way when things got ugly, pretending there was nothing wrong in our chaotic house, that we were a normal, happy family. Judging from the House Beautiful photo-op she’d created here, she hadn’t changed a bit.

If I’d had any remaining doubts about claiming my legal share of this…this “all-American dream house,” they evaporated in the heat of my rage. She might believe her own crap, but I sure didn’t.

I shoved the gearshift into Park and turned off the motor. That’s when I heard the barking—Tripod and some other yappy creature. From under the porch a little white streak burst through a bed of white impatiens and tore up the front steps, followed closely by my lumbering, brindle mutt. Up the steps Tripod started, then paused, his one forefoot on the top step, daring the little dog to try and escape him now.

Tripod hadn’t treed a raccoon. He’d porched a poodle. He’d made his intent to dominate known in the only way the other dog would understand. That’s what I had to do with Alice.

I jumped down from the Jeep and marched up the neatly edged gravel walkway, feeling my heels sink between the pebbles with every step. Damn, I should have changed shoes, too.

Just as I reached Tripod and the base of the steps, the front door opened. Only it wasn’t Alice. A lanky kid in a faded Rolling Stones T-shirt burst through the screen door. First he scooped up the fluff-ball of a dog. Then he crossed barefoot to the edge of the porch. “Hey,” he said. “You looking for my mom?”

His mom. So Alice had kids.

“Hush up, Tripod,” I muttered, catching hold of the dog’s collar. “Yeah. I am—if your mom is Alice Blalock.” Blalock was Alice’s father’s name. Since Mom hadn’t been sure who my father was, I’d remained a Vidrine, like her.

“Alice Blalock Collins. I’m her son, Daniel.” He gestured to Tripod. “What happened to his leg?”

“A big car. Where’s your mom?”

“She’s up at the church. Who are you?”

I planted one fist on my hip and shrugged my hair over my shoulder. “I’m your aunt Zoe.” I’m your bad-seed relative your mother probably never told you about. “I’m your mom’s baby sister. So. When will she be home?”

I could see I’d shocked the kid—my nephew, Daniel. While he went inside and called Alice, Tripod made a methodical circuit of the yard, marking every fence post, tree trunk and brick foundation pillar. He hadn’t done this at any of the rest stops we’d slept at or the Motel 6’s I’d snuck him into. But somehow he seemed to know we’d reached our destination and that this place belonged to him.

At least half of it did.

As for me, I sat down on the porch swing and tried to get my rampaging emotions under control. I was here. It wasn’t what I’d expected. Then again, I don’t know exactly what I did expect. Mom had been dead twenty years, and I’d been gone even longer. It made sense that Alice would have changed things. Of course her life would have gone on. Mine had. She wasn’t a nervous twenty-year-old anymore. Just like I wasn’t a scared seventeen-year-old.

But today, back here in this place, I felt like one all over again. And I didn’t like the feeling.

“Come here, Tripod,” I called. “Good boy.” I fondled his ragged ears until his crooked tail beat a happy tattoo. “Good boy. You showed that snooty little cotton ball who’s boss, didn’t you? Come on. Get up here with me.”

I hefted his fifty-five-pound bulk up onto the swing beside me, somehow reassured by his presence. We were a team, me and Tripod. A banged-up pair of survivors who weren’t taking anybody’s crap. Not anymore.

From my perch on the swing I peered through the window into the living room. I saw an upright piano and two wing chairs with doilies on the headrests. Beyond them I saw Daniel pacing back and forth in the dining room, talking on the phone. I stilled the swing and strained to hear his end of the conversation.

“…yeah, Zoe. And she’s definitely not dead.”

She’d thought I was dead?

“But if she’s my aunt, how come you never—”

He broke off, but I filled in the empty spaces. How come she’d never mentioned me to him? No wonder he’d looked shocked. The kid, if he’d even known of my existence, thought I was dead.

Now that made me mad. It was one thing for Alice to wonder if I was dead. After all, I hadn’t talked to her since right after Mom died. And if she didn’t follow the music industry and see my occasional photo in an appearance with one of my several rocker boyfriends through the years, she might be excused for speculating that I was dead. But to not even tell her son that she’d ever had a sister?

I snorted in disgust. Obviously nothing had really changed around here except for a fresh coat of paint. Underneath, our family was as ugly and rotten as ever. Alice might want to pretend I didn’t exist, and she definitely wouldn’t want me in her house.

Problem was, it wasn’t her house. It was our house.

One thing I was certain of: my mother wasn’t the type to have written a will. Too conventional for her. Too establishment. That meant, according to Louisiana laws, which I’d checked into just last week, since Alice and I were my mother’s only children, we were her only heirs. And we shared equally in her estate.

Daniel edged out through the front door and stared uneasily at me. I raised my eyebrows expectantly.

“She’ll be here in just a minute.”

I smiled and with my toe started the swing moving. I needed to go to the bathroom in the worst way. But I wasn’t going to put this kid on the spot by asking to use the bathroom. I had to keep in mind that he wasn’t a part of my issues with Alice and this place. I remembered what it was like to be caught in the middle of warring adults, and I didn’t want to put him in that position.

“How come you’re not in school?” I asked, trying to be conversational.

“I’m homeschooled.”

“Homeschooled?” Oh, my God. Hadn’t Alice learned anything from our experience with Mom? I managed a smile. “So. What grade are you in?”

“Tenth. Sort of. Eleventh grade for English and history. Ninth for math and science. It averages out to tenth.”

“Yeah. I see. You have any brothers or sisters?”

“No.” He shook his head. “Just me.”

I nodded. “So…You like the Stones?”

He looked down at the logo on his T-shirt, a classic Steel Wheels Tour-shirt from the early nineties. It was probably older than he was. “Yeah,” he said. “They’re like real cool for such old guys.”

Okay, Aunt Zoe, here’s your chance to impress your nephew, who’s obviously never even heard of you. “You know, I’ve met Mick Jagger a couple of times. Partied with him and the rest of the Stones.”

His eyes got big. “You have?”

“Uh-huh. Keith Richards, too.”

His eyebrows lowered over his bright blue eyes. Alice’s eyes. Mom’s eyes. “My mother says Keith Richards is depraved.”

“Depraved?” I would like to have argued the fact. Anything to contradict Alice. But what was the point? So I settled for a vague response. “You know, not everyone who lives a life different from our own is depraved.”

“I didn’t say they were.” He looked at me, this earnest kid of Alice’s, and I suddenly saw him as girls his age must see him. Tall, cute, maybe a little mysterious since he didn’t go to regular high school.

Or maybe weird and nerdy, an oddball since he didn’t go to regular high school.

Damn, but I’d hated my brief fling with the local high school.

No. What I’d hated was being the girl who lived in the hippie commune. The girl whose mother never wore a bra. The girl who didn’t have a clue who her father was. At least Alice had her father’s last name. But I was just a Vidrine, like my mother, and other kids were merciless about it. Love Child, they’d called me, and sung the Diana Ross song whenever I walked by.

Tripod put his head on my knee and whined. That’s when I realized I was trembling, vibrating the swing like a lawn-mower engine. Even my dog could tell I was wound just a little too tightly.

I looked away from Daniel, wondering when Alice would get here, then wondering how I was supposed to make this plan of mine work if just talking to this kid got me so upset.

“Did it hurt?” he asked. “You know, when the car hit your dog?”

A new subject, thank God. “I guess it did. The first time I ever laid eyes on Tripod he was flying off the front fender of this giant black Hummer.” Which Dirk, my ex-ex-boyfriend had been driving. “I stopped and so did this other car.” Dirk drove off and left me on the highway. “Anyway, we got him to a vet, who said his leg was shattered and did we want to put him to sleep or amputate.”

“Wow. You saved his life and adopted him?”

I shrugged. It sounded so altruistic the way he said it. The truth was, I’d charged the vet bill to Dirk’s credit card, then kept the dog to remind me how glad I was to be rid of that SOB. Never date drummers, I’d vowed after that six-year fiasco had ended.

But at least I had Tripod. We’d been together for almost four years now. I rubbed his left ear, the one that had a ragged edge from some incident that predated the Hummer. “He may be an ugly mutt, but he’s my ugly mutt.” And the only semitrustworthy male I’d ever known.

We both looked up when a Chevy van pulled into the driveway, swung past my Jeep and pulled around the side of the house toward the garage.

For someone who hadn’t seen her only sister in over twenty years, Alice sure took her sweet time. She came in through the back door. I caught a glimpse of her in the house—much slimmer than I remembered but still pleasantly plump. She paused at a mirror and fiddled with her hair. Even then it took her another full minute to join us on the porch. I guess she had to brace herself. After all, she obviously felt like I’d risen from the dead.

As kids she and I hadn’t exactly been close. You’d think we would have clung to each other in the midst of all the chaos thrown at us. Instead we’d become each other’s primary targets, both of us competing for the meager fragments of Mom’s love and attention.

Later, when I’d begged her to leave with me, I couldn’t believe she meant to stay. As furious at her as I was at our mother, I’d left without her, scared to death but determined to go.

I’d had my revenge two years later, though, when she called me about Mom being sick. I told her point-blank that I didn’t give a damn about Mom and what she needed. Four months later Alice had tracked me down again to say Mom had died, and what did I think we should do about a funeral?

Though now I know it was illogical, my response at the time had been utter rage: at Mom for dying and at Alice for crying to me about it. And maybe at myself for feeling anything at all for either of them.

“Don’t you get it?” I said to her in this cold, unfeeling voice. “I don’t care what you do with her or anything else in that hellhole of a house. I left Louisiana a long time ago, Alice. Get over it.”

And that had been that. Our last conversation.

But even though that had been twenty years ago I could feel the old animosity rise, like a fever that the antibiotic of time had only held at bay. We were still competing for Mom’s scraps. Only in this case it would be our inheritance.

“Hello, big sister,” I said with a wide, for-the-camera smile.

Alice’s wasn’t quite so eager. “Zoe. Well, hello.” She stood there, just staring at me as if she hadn’t believed Daniel, as if she wasn’t sure she even believed her own eyes. She glanced at Daniel, then away, clearing her throat. “I see you’ve met my son.”

With my left foot I set the swing into motion. “Yes. He seems like a great kid, though I could swear he’s never heard of his aunt Zoe.”

If it was possible her pinched expression grew even tighter. “Go inside, Daniel.”

When he didn’t jump right up, she turned a stern look on him. “I said go. Finish the history chapter—”

“I already did.”

“Then start the next one. And take off that awful T-shirt!”

He muttered something under his breath, but he did as she said. When he opened the door, however, the poodle slipped out. One yip and Tripod sprung off the swing, nearly knocking Alice over when she snatched her obnoxious pet up from the jaws of death.

“Make him stop!” she yelled at me while Tripod bayed at the fur ruff she held up over her head.

It would have made a hilarious photo, my ugly, three-legged hound up on his hind legs trying to reach her sweetly groomed little dog while she screamed bloody murder. A great album cover for a band like Devil Dogs.

Slowly I unfolded myself from the swing. “That’s enough, Tripod. Come on, now.” He could probably tell I didn’t really mean it. That’s why I had to haul him back by the collar while Alice put “Angel” back in the house.

Then still not sitting down, she said, “So what brings you back to Louisiana?”

I perched on the porch rail like I used to when I was a kid, before it was torn off in a drunken rage by one or another of Mom’s so-called boyfriends. “This is home, isn’t it? I’ve come home.”

She got this wary look on her face. “What do you mean? You’ve been gone over twenty years, and all of a sudden, out of the blue, you decide it’s time for a visit?”

“Something like that. Only this isn’t a visit, Alice. I’m back to stay.”

That’s when she sat down. I guess the shock made her knees weak. “You mean you’re moving back to Louisiana? But…you said you hated this place. You called it a hellhole.”

In my opinion it still was. But I only shrugged. “Things change. Not only am I moving back to good old Oracle…” I said, watching her wariness turn to horror. “I’m moving back here,” I added, sweeping my hand to include the house and its forty-plus acres. “In case you’ve forgotten, it is half mine.”

Just like her son, Alice’s first reaction to the little bomb I’d laid on her was to run inside and get on the phone. I suppose she was calling her hubby so he could hurry home and somehow make me leave. Like that would work. It might have been an angry impulse when I ditched Palm Springs and my sunbaked, half-baked existence there. But I’d had six long days of driving with only a nauseated dog and a string of country and western stations to keep me company. Lots of time to think. And now I was committed to my plan. I wanted my half of our inheritance, and I wasn’t leaving here without it. Keeping this farm was the only thing my mother ever did right. With my share I could start a new life, someplace where neither G. G. Givens nor my mother’s ghost could find me.

So Alice could call her husband and all his kin, too. But she wasn’t getting rid of me until I had my money.

I heard voices from inside the house. Daniel was yelling at his mother and she was yelling back. But I couldn’t see them through the window. Well, it was my house, too, wasn’t it? So I got up and walked inside.

“…it’s still a lie,” Daniel shouted down at his mother from halfway up the stairs. “A lie of omission. Just like you said I did when I told you I was going to New Orleans with Josh and his big brother but didn’t tell you we were going to the Voodoo Fest.”

“That’s different,” Alice retorted. “You knew if you asked me to go to that Voodoo thing that I would say no. That’s why you didn’t tell me, and that’s why it was still a lie.”

“And you thought I would approve of you pretending you didn’t have a sister?”

Good point, kid. I crossed my arms, waiting for Alice’s reply. But when Daniel’s eyes shot to me, she turned around, too. She was shaking. I could see it on her pale face. It should have made me happy, seeing my Goody Two-shoes sister caught in a lie. Instead it made me vaguely uncomfortable. I didn’t care if she felt bad. But some small part of me didn’t want to make her look bad in front of her son. I remembered how awful it used to feel when my mom pulled some monumental screwup, some embarrassing public incident that I couldn’t overlook even with my hands over my eyes and my thumbs in my ears.

“She thought I was dead,” I blurted out. “Okay? I’ve never been very good about keeping in touch, so…” I shoved my hands into the back pockets of my jeans and shrugged. “You might say we’ve never really been close. But now I’m back,” I added, switching my gaze to Alice. “So where should I put my stuff?”

When she just stared at me with big, round—scared—eyes, Daniel answered for her. “There’s plenty of room upstairs. Two guest rooms plus mine and a study.”

“Daniel—” Alice raised a hand to him, then let it fall in the face of his anger and hurt. His mother had lied to him. I guess that hadn’t happened before. Lucky boy.

“Fine,” I said into the tense standoff between them. “It won’t take me long to unpack. Then maybe you and I can have a nice long talk, Alice, and catch up on the past—” twenty-three “—few years.”

I was just lugging my second-to-last load up the front steps—why had I brought so many records and books?—when a third car turned into the yard. A burgundy Oldsmobile. An old man’s car, and given that the guy who got out had a full head of white hair it seemed like I’d guessed right.

I ignored him and let the screen door slam as I went inside. Once I got everything in my room, I planned on taking a bath. Then I was getting the hell out of this house for a while, because already it was giving me the creeps. It would take more than a few coats of Sunny Yellow and Apple Green latex to paint out the stains of my miserable childhood.

Outside I heard Tripod barking, then a man’s voice yelling, “Shoo. Get away!” Then, “Alice. Alice!”

Upstairs I looked at Daniel’s closed bedroom door. He’d been in there ever since his fight with his mother. Downstairs I heard Alice fussing at Tripod. I guess the man of the house got inside unscathed. I dug around for a dog biscuit before heading downstairs for the last box. Tripod deserved a reward for sticking up for me.

In the front parlor Alice sat hunched over on an elaborate settee, her husband next to her with an arm around her bowed shoulders. When he heard me on the stairs, he looked up and glowered at me. “Is this any way to treat your only sister?”

I planted one fist on my hip. “I’ve ignored her for twenty-three years and she’s done the same to me. How does that make me the villain and her the victim?” Then I strode forward and stuck out my hand. “Hi, I’m Zoe. And you must be…”

By now Alice had bucked up enough to speak for herself. “This is Carl Witter, a…a friend of mine.”

A friend? He looked a bit possessive of her to merely be a friend. And he ignored my hand. “Oh,” I said, pulling it back. “A friend. Where’s your husband?”

If possible, Carl’s pale eyes turned even colder. “Reverend Collins died thirteen months ago,” he bit out. “Which you would have known—”

“If she had told me,” I threw back at him. Alice had been married to a minister? I pushed that question aside. “I guess that makes you the new boyfriend.”

“I’m her friend,” he bit out. “And I’m not about to let you take advantage of her sweet nature, especially with an impressionable young man in the house.”

“An impressionable young man who didn’t know till now that he had an aunt.” The more I thought about that fact, the madder I got.

He leaped to his feet. “Given the aimless, Godless life you’ve led!”

“Stop it, Carl,” Alice begged, tugging on his arm.

“You don’t have to let her stay here,” he told her. “This is your home.”

“Which happens to be half mine,” I said.

That stopped him cold.

“Look,” I said before he could start up again. “Why don’t you and Alice go back to whatever you were doing. I can finish moving in without any help.” Then flashing them a smug smile, I flounced out of the house.

From behind a closed door—what used to be the “Meditation Room” when we were kids but what had actually been the “High Way Room” for getting loaded—I heard Angel yapping. From his spot on the porch, surveying his new domain, Tripod let out a warning bark.

“Good boy,” I told him, rubbing his ears the way he liked. “I think we’ve each won the first skirmish.” It was mighty interesting that, considering she thought I was dead, Alice and her creaky boyfriend sure seemed to know all about my “aimless, godless life.”

I straightened up and looked around me. The porch, the house, even the grounds looked nothing like how I remembered. But the ghosts of my childhood were still there, waiting to jump out at me. God, I hoped it didn’t take long for Alice to give me what was my due. I didn’t think I could last very long in this haunted house of ours.

CHAPTER 2

I hung up my clothes, put the folded things into the pretty oak dresser, lined up my shoes in the bottom of the closet and stacked the boxes of records and books in the corner behind the bed.

“Now what?” I said to the world at large. I’d accomplished the first part of my plan. That had turned out to be the easy part. Now I needed a plan for Part Two.

My stomach gurgled and I rubbed one hand over it. “You stay here,” I told Tripod, who’d already stretched out on the faintly dusty pine floor. “Guard my stuff while I…”

Go somewhere. Do something. I wasn’t sure what.

All I knew was that I wasn’t sitting up here in the room my mother had called the Venus Trap. I’d once seen three women and two men doing stuff to each other here that no eleven-year-old should ever be exposed to. The room was painted pale blue now, with eyelet curtains framing the two windows and an old-fashioned chenille bedspread covering the pretty iron bed. But I could see the black and hot-pink walls beneath this pretty facade as clearly as if the paint was bleeding through.

“Ugh.” I shuddered and closed the door behind me. Directly across the hall Daniel’s solid door seemed to beckon me. I knocked, a short lilting rhythm. After a minute he cracked the door.

“Hey. Listen, I’m going out. You know, to drive around and check out the changes in town.” I made that decision barely a split second before the words spilled out of my mouth. “You need anything? A ride anywhere?”

He shook his head, not meeting my eyes. But he didn’t close the door in my face either.

“Look, Daniel. I didn’t come here to make trouble between you and your mother. She and I…well, let’s just say we weren’t raised in a real close family. I’m sure she has her reasons for not telling you about me.” Lousy reasons but reasons all the same.

“But she lied to me.” He lifted his eyes—Mom’s eyes—to me.

“Look, kid. Everybody lies. All the time.”

“That’s not true.” When I only shrugged, he said, “Well, they’re not supposed to.”

“But they do. The trick is to figure out their motive. Are they trying to hurt you with the lie or just trying to help themselves out of a bad situation?” Then for some stupid, maudlin reason I added, “Or maybe they’re lying because they think it will somehow help you.”

“Well, it didn’t help me.” He gave me this long, steady look. “Why’d you decide to come home now?”

I didn’t want to say. It was one thing to demand what I was owed from Alice. It was another thing to discuss it with her kid. “I figured twenty-four years away would have been too long. So,” I went on. “Do you need anything while I’m out?”

He hesitated only for a second. “Maybe I will take a ride with you. To my friend’s house.”

“Okay. Let’s go.”

Tripod started to howl. How he knew I was leaving the premises was beyond me. Daniel gave me a questioning look. Normally I’d take the dog, too. But I didn’t trust Carl Witter not to take my stuff and throw it outside. I knew Tripod wouldn’t let him get past the door.

We didn’t see anyone in the living room. “I’m going to Josh’s,” Daniel called toward the kitchen.

No answer.

“She’s not going to be happy when she finds out I drove you,” I pointed out as we climbed into Jenny.

“I’m fourteen, not four,” he muttered. “Almost fifteen. I can take care of myself.”

“Okay then.” I started up Jenny’s cranky engine. “Which way?”

Driving down the old roads of my childhood was like negotiating a foreign country. Like a Twilight Zone episode where everything was so strange and yet somehow familiar. The town square and St. Brunhilde’s church, and the Landry mansion were familiar. The P.J.’s Coffeehouse in the old Union Bank building, the Wendy’s on the corner of Barcelona Avenue and the Walgreens opposite it were all new. The park that meandered along the river was the same. Bigger trees and bigger parking lot but otherwise the same. That’s where that stupid Toups kid and his friends had chased me once, wanting to know if it was true that hippie kids didn’t wear underwear. I’d jumped into the river to escape them and nearly drowned.

Mother had laughed when I’d finally got home, shivering in my wet clothes. I’d shown them, she’d chortled.

Her boyfriend at the time, Snakie somebody or other, had stared at my fourteen-year-old breasts beneath my clinging knit top and promised to get even for me. And he had. The old sugar-in-the-gas-tank trick. I heard Bonehead Toups had to go back to his bicycle. Sweet justice, literally.

But of course, it had a downside. Snakie had wanted a sweet little reward for being so heroic. A reward from me, not my mom.

Unfortunately for him, after the river incident I’d checked out a library book on self-defense for women. That knee-to-the-groin business really works. He moved out the next week.

“Turn left up there, by the gas station,” Daniel said, bringing me back to the present. We went down an old blacktop to just past where it turned to gravel. “There.” He pointed to a pair of shotgun houses with a rusty trailer parked farther behind them.

“Do you need me to pick you up later?” I might as well ingratiate myself with him before his mother turned him completely against me.

“No. Josh’ll give me a ride home.”

“This Josh is old enough to drive?”

He grinned. “He has a four-wheeler. We’ll take the back route through the woods.”

I grinned back. “Sounds like fun.”

“Yeah. But don’t tell my mom that part.” His grin faded. “She says it’s too dangerous.”

“It is too dangerous. But that’s what makes it so fun.”

“Yeah.” He slammed the door, then gave me a head bobble that I guessed passed for “thanks.” “See ya.”

Then it was just me and Jenny Jeep and my old hometown.

On the surface, Oracle, Louisiana, is just like every other small town I’ve ever been in: an Andy of Mayberry downtown, a big, brick elementary school, a couple of churches. It had more trees than most. And more humidity. I’d been in a lot of little towns, especially when I toured with Dirk and his Dirt Bag Band. I’d done everything on those tours: arranged the shows, driven the bus, collected the money. Collected the band too when they were too stoned to find their way back to the bus.

I hadn’t collected very much money for myself, though. I was Dirk’s girlfriend. What did I need with money?

His words, not mine.

That’s when I’d started my T-shirt and jewelry sideline. Small-town wannabe rockers and wannabe groupies had snapped them up. Too bad I hadn’t saved more of that money. But Dirk had thought what was mine was his, and he would have blown my profits on booze and drugs and music equipment. So instead I blew them on becoming the best-dressed rock band manager you ever saw.

Anyway, you see one small town, you’ve seen them all.

I turned onto Main Street. Creative street name isn’t it? That’s when I saw the library. Except for the white crepe myrtles flanking the front doors, it hadn’t changed a bit. There weren’t many places in this town I had good associations with; the library was one of them.

I parked in front of the newspaper office next door to the library. Through the paper’s front window I saw an old woman staring at a computer screen. So the Northshore News had gone high tech. With only a few keystrokes they could more easily report on this weekend’s softball tournament or the Jones’s fiftieth anniversary celebration. Woo hoo. Big news.

At least there weren’t any parking meters to feed. I jumped down from Jenny, locked the door and slammed it.

“You must be from out of town.”

Startled, I looked up. “Why do you say that?” I replied to this guy who had stopped in front of the newspaper office, his hand on the doorknob.

“You locked your car. People around here don’t do that.”

His comment shouldn’t have made me feel so defensive, but I guess I was feeling extra touchy today. Added to that I wasn’t in the mood to be hit on, especially by a guy who had to know how good-looking he was. “They don’t? Well, I’ve been mugged in a small town like this.” A drunk coming out of one of the Dirt Bags’ concerts, who got frustrated when I wouldn’t go home with him. “And had my car broken into.” Amps stolen out of the band’s bus.

I hiked my purse onto my shoulder and tossed my hair back. “So you see, I’ve learned not to be too trusting. Even in a nice little town like this.”

He tilted his head to one side. “Sorry to hear that.” He stared at me. At me, not my chest, for one long, steady moment, the kind of look that forced me to really look at him in return. If I were looking for a guy, he would have fit the bill just fine. If I were looking. Several inches taller than me, even in my heels. Wide shoulders, trim build. Not cocaine skinny like too many of the men I’ve known. Not self-indulgent fat like too many others. Which left the equally unappealing other third of men: probably a narcissistic health nut trying to stave off middle age.

“I’m Joe Reeves.” He stuck out his hand.

I didn’t want to know his name or to know him. But I had no real reason to blow him off. So I took his hand—big, strong and warm—and shook it. “Zoe Vidrine.”

“You visiting here, Zoe? A tourist?” he asked, once I’d pulled my hand free of his.

“Oracle gets tourists?”

“You’d be surprised. Oak trees dripping with Spanish moss. Natural spring waters. We have our own winery now and a railroad museum. Not to mention all the water sports on Lake Pontchartain.”

“That cesspool?”

“It’s clean now. Regularly passes all state requirements for swimming.”

“Gee, it all sounds so exciting.” But I softened my sarcasm by laughing.

He grinned. “That’s the point. It’s quiet and relaxing here. The perfect escape from the rat race.”

“Yeah? Well, we’ll see.”

“So you’re not a tourist. That means you’re visiting someone.”

I glanced away from his lean, smiling face. He was too smooth, too easy to talk to. Then I realized he’d been going into the newspaper office, and all my senses went into red alert mode. “You work here?” I gestured to the office.

“Sure do. Editor-in-chief.”

Editor-in-chief? Shit!

“Plus beat reporter, features reporter, obituary writer and head of advertising. We’re a small outfit, Wednesday and Sunday editions only.”

“Cool,” I said. But I meant just the opposite. The last thing I needed was for some local-yokel reporter to figure out that Zoe Vidrine was actually G. G. Givens’s ex-girlfriend Red Vidrine and try to make a big deal about it.

I shifted my purse to my other shoulder. As I did so, his gaze fell to my body. Just one swift, all-encompassing glance. But it was enough to remind me that he was a man like every other man in the world. To them I was just a hot babe who looked as if all she wanted was his leering, drooling attention. “Well. See you around,” I said. Then I turned and made for the library, my sanctuary when I was a kid, and hopefully my sanctuary now. I willed myself not to look back at him, but I knew he was watching. I felt it.

Inside, the library was cool and dim and so much like when I was a kid that a wave of relief shuddered through me. Same big wide desk; same art deco hanging lamps; same oriel window where I used to sit for hours reading everything from Seventeen Magazine to Alexandre Dumas to Shere Hite. I learned a lot about sex from Shere Hite. Too bad more men hadn’t read her.

Anyway, my oriel was just like I remembered except for new, dark green upholstery on the cushions.

I looked around. Mr. Pinchon couldn’t still be the head librarian. I approached the woman at the front desk.

“Can I help you?” She smiled like she really meant it.

“I was wondering, does Mr. Pinchon still work here? When I was a kid he used to suggest a lot of books for me to read.”

“Mr. Pinchon? I don’t know him. Oh, wait. He retired a couple of years ago before I started working here.”

“Oh.” I looked away. I shouldn’t feel disappointed, but I did. The one person who’d understood me, who’d cared enough to make sure I read across the spectrum. He’d made me a lifelong reader—and a sometimes writer. But of course he was gone. He was old back then. By now he was probably dead.

“Can I help you with anything else?” the librarian asked. “Do you have a current library card?”

“No.”

“Well, we can easily remedy that.” She handed me a pen and a registration form, and I started to fill it out. Until I caught myself. I didn’t need to advertise that I was in town. I’d planned all along to keep a low profile, to just swoop down, collect my inheritance and split.

Then why’d you tell that newspaper guy your name?

I slid the pen and paper back across the desk. “I’m just in town for a week or two. Um…could you direct me to the microfilm records, the ones for the Northshore News?”

“Sure. You know, their office is right next door if you need to talk to Joe or Myra. She’s worked there forever.”

“Thanks.” I gave her a bland smile. “How long has he been there?”

“Joe? Let’s see now. I think three—no, four years. He used to be a big-time reporter in New Orleans. For the Times-Picayune. But when he and his son moved here, he decided celebrity news wasn’t as exciting as it used to be.”

I stiffened in alarm. Celebrity news? That’s what he’d written about? Great.

“Well, I can see why he left it behind,” I said. “Most of it’s a lot of PR hype. But what I’m looking for…” I went on, wanting to change the subject “…is local news from the mid-eighties on.” I’d left town in 1983, Mom had died in 1986 and Alice had obviously married sometime after that. I wanted to see what had been said about the Vidrine hippie commune, how it had petered out and how Alice had changed everything. Because like it or not—like her or not—I had to admit she’d done an amazing transformation of the place.

Some time later the librarian—Kenyatta was her name—startled me as I hunched over a microfilm screen. “Sorry to disturb you,” she said. “But the library closes in fifteen minutes.”

“What time is it?”

“Quarter to six.”

I’d been here three and a half hours?

“Okay. Thanks. I’ll finish up here in a minute. What time do you open tomorrow?”

Right after she left I went back to the article I’d been reading about the christening of Daniel Lester Collins at the Simmons Creek Victory Church. The picture was grainy, but it was obviously Alice holding her newborn son. Next to her stood a gaunt, older man. Surely that wasn’t her husband?

But it was. The Reverend Lester Collins had presided over the christening of his firstborn child. He had a huge grin on his face.

And why shouldn’t he? He had a young, pretty wife who—knowing Alice—had probably done his every bidding. And she’d given him a son. For him, life must have been pretty damn good.

Had it been good for my sister?

As I left the library and headed up Highway 1082 to the farm, everything I’d read rolled around in my head. Mom had died of AIDS.

About three months before her death, her illness became public knowledge. In 1986 rural Louisiana that had been a horror too huge to ignore, and all sorts of hell had broken loose. There had been letters to the editor. Demands that the farm be quarantined, that the house be burned down to kill the germs. The American Civil Liberties Union in New Orleans had actually become involved.

By the time Mom died, only she and Alice were left on the farm. All Mom’s freeloading friends had split. There was no official obituary notice, but afterward there had been a slew of articles and more letters to the editor about the wages of sin and the plague festering at Vidrine Farms.

I frowned and turned down the azalea-lined driveway. How had Alice stood it? Why on earth had she stayed? And why, when she called, hadn’t she told me it was AIDS?

Then again, that wouldn’t have changed my reaction.

I sighed. Despite my carefully cultivated disdain for my spineless, mealymouthed sister, I had to give it to her. She’d showed them all in her own, do-gooder way. I would probably have sponsored a rock festival on the farm and invited the most offensive acts I could find. Then I would have ended it by making a giant bonfire out of that house.

I pulled to a stop and stared at the house now, so pretty and neat and innocuous-looking. I would have lit the fire gladly but not for the reason ranted about in that stupid newspaper. I would have burned it down for my own satisfaction, to obliterate once and for all the miserable childhood I’d lived in it.

The sun was sinking behind the house, casting it in soothing shadows, a photo-op for This Old House. I closed my eyes and rested my forehead on the steering wheel. Burning it down wouldn’t have helped. I would have loved doing it, watching the destruction, feeling the heat, smelling that scorched wood stench. But it wouldn’t have changed anything. I was the product of my rotten childhood, pure and simple. And nothing symbolic would change that.

But collecting my half of its value in cold, hard cash would go a long way toward easing my pain.

I slammed out of the car, resolved in my goal to just collect my due and get started on a new, normal life. From upstairs I heard Tripod’s mournful howl, and I spied his ugly snout pressed against the window glass. He probably needed to visit the nearest tree.

I trotted up the steps, crossed the porch and walked into the house—only to be confronted by Carl.

“The least you could do is knock.”

I ignored him. “We need to talk,” I said to Alice, who stood farther down the hall, in the doorway to the kitchen. “By the way, better collect your toy dog. I’m about to let Tripod out.”

“And that’s another thing,” Carl hollered up after me. “That dog is too big to be allowed indoors—”

He broke off when Tripod charged down the stairs in one big hurry. The dog leaped up, planting his one front paw on the front door, barking his impatience.

“What’s the matter?” I cooed to him once I reached the door. “You’re acting like an old man with prostate trouble.” I turned pointedly to Carl and smiled. He looked a good fifteen years older than Alice and not particularly well preserved.

I opened the door, Tripod ran out, then I turned to Alice. “Where do you want to go to talk?”

“Can it please wait?” she asked, her voice soft, her hands a nervous knot at her waist.

My sister is really pretty. She takes after my mother with her sunny hair and vivid blue eyes. She was over forty now and still heavier than was considered healthy. But she was a lot thinner than I’d ever seen her. She looked good. Sweet and soft. Put her in a blue bonnet, and she’d be my image of Little Bo Peep.

I, meanwhile, apparently took after my unknown father. Red hair, pale skin. Thank God not too many freckles. I was taller than Alice and Mom, with bigger boobs—which I sometimes loved and sometimes hated. Let’s just say they have their uses and have got me past a lot of locked doors a lesser endowed woman couldn’t have entered.

But that was neither here nor there. “Wait for what?”

“Daniel’s missing.”

“Missing? No, he’s not. He’s at his friend’s house. He asked me for a ride.”

“Without telling me?” All of sudden Alice’s soft side turned fierce.

“He told you he was going. I heard him.”

“Well, I didn’t. What friend?”

“Some kid. I don’t know. Josh,” I said as the name came back to me. “Yeah, Josh.” Of Voodoo Fest and four-wheeler fame.

Alice and Carl shared a look. “I’ll go get him,” Carl told her. “If you’ll be all right,” he added, shooting me an aggrieved look.

“I’ll be fine,” she said, patting his arm.

I slapped my hands, rubbed them together, and grinned. “Well, good. That’s settled. So, big sister. Shall we have that talk?”

I walked past them and into the kitchen. My stomach had started growling the moment I drove up. Since the house was half mine, I decided that everything in it was, too.

I stood in the open refrigerator checking out the healthy selection of white bread, bologna and processed cheese. Yuck. I strained to hear the muffled conversation in the hall. Though I couldn’t make out most of the words, I didn’t have to be clairvoyant to know Carl was royally pissed.

Poor Daniel. I didn’t envy him the ride home.

Bending back to the refrigerator, I noticed some bacon and took it out, then found eggs. “Do you have any grits?” I asked when Alice came in. “I haven’t had any decent grits since—” since G.G.’s last Southern tour “—since forever.”

She handed me a Martha White bag and a pot, then sat down while I started the grits, put the bacon in the microwave and slapped a thin pat of butter into a cast-iron skillet. I was seriously hungry. “Want any?” I added as an afterthought.

“No.”

I worked in silence as the grits bubbled and thickened. Once I turned them off, I broke three eggs in the skillet. “So here’s the deal,” I began as I scrambled them. “Mom was Granddad’s and Nana’s only heir, and we’re her only heirs.” I turned off the skillet and scraped the eggs onto a plate. “This place is half yours and half mine. And I want my half.”

She frowned. “You want me to split the farm in half?”

“I don’t want any part of this godforsaken place,” I said. “What I want is half the value of the property. And I want it as fast as I can get it.”

I sat down at the kitchen table and started to eat, as if I was totally nonchalant and this conversation was not absolutely critical to my escape from my past—my pasts in both Louisiana and California.

She shook her head. “But I don’t have any money, Zoe. I can’t afford to buy you out. And this place is hardly god-forsaken. It might once have been but not anymore. Lester and I made it into a good home. A God-fearing home.”

“Well, good for you. But that doesn’t change anything. It’s still half mine and I’m willing to sell you my share. Surely your wonderful husband had life insurance.”

She stiffened. “He only had a burial policy.”

“You’ve got to be kidding! With a family and all—”

“He had health problems. A bad heart. Life insurance was too expensive, okay?”

I wanted to ask how old he’d been when they got married, fifty? Sixty? But I didn’t. “So he left you in the lurch. Isn’t that just like a man.” I fixed her with a sharp eye. “Is that why you’re hooking up with good ol’ Carl? Need another sugar daddy?”

Finally I got a real rise out of her. “Just because you’ve lived a debauched life doesn’t mean the rest of us have!”

I gave a sarcastic snort. “I was here for seventeen years, Alice. I know exactly what sort of debauched life we lived.”

“I was raised in it, yes. Just like you. But I never lived my own life that way.”

“What makes you think I did?”

Her eyes narrowed. “Come on. I saw that music video, Zoe.”

“Really? Which one?”

“There was more than one?” Her face was a study in horror.

I just smiled, folded my hands on the table and nodded. But inside I was raging. How dare she judge me?

“The one I saw was about ten years ago. You were dancing in this low-cut dress, rubbing up against some guitar while this man watched you.” She shuddered.

I, too, shuddered in disgust when I thought of Dirk and the Dirt Bags, but for an entirely different reason, though that wasn’t her business. “How did you ever come to see that video?”

“Sue Ellen Jenkins. She saw it and she thought it might be you. So she recorded it and showed it to me.”

“So, what did she think?”

Her chin started to tremble and it took me aback. Why was she getting so upset? “I told Sue Ellen it wasn’t you,” she said in a shaky voice. “I told her you’d died in a car wreck in Texas.”

CHAPTER 3

“You told everyone that I was dead?”

It didn’t matter that Alice looked contrite. It didn’t matter that she ducked her head in shame. She’d told the whole world that I was dead even when she knew for a fact I wasn’t. Except for her son, I was her last living relative if you didn’t count her father, who’d disappeared long before I was born.

For her I was it. Yet she’d rather I be dead.

You abandoned her first.

I didn’t want to think about that, but it was an inescapable fact. When she wouldn’t run away with me, I’d run away without her and had never looked back. But that hadn’t been about her. It had been about this place. I’d had to get away; she’d been content to stay. That’s why now I ignored any excuses she had for her lie about my early demise. “You told Sue Ellen Jenkins that I was dead? Why? Were you afraid it would dirty your standing in the narrow, self-righteous church community you married into?”

I shoved my plate across the table, crossed my arms and glared at the top of her bowed head. Tears were dripping from the end of her nose. Phony, crocodile tears. “Tomorrow I’m getting a lawyer, settling the estate and putting this place up for sale.”

Her head jerked up. “You can’t do that!”

“Wanna bet? You can hire a lawyer to fight me, Alice. But that’s going to cost a lot of money, and in the end I’ll still get my inheritance. You can’t stop me.” I paused a beat. “So why not just strike an agreement with me now?”

She stared at me though teary eyes. “You don’t understand. I can’t. This is my home, mine and Daniel’s.”

“Oh, come on! There’s plenty enough land to go around. Just get the property appraised, split it into two parcels of equal value, and if you don’t want to buy my portion, then I’ll sell it to someone else.”

She shook her head. “It’s not that simple.”

“Well, that’s just too damned bad, isn’t it? You can’t poor-mouth your way out of this. You’ve lived here over twenty years, Alice. That’s a lot of free rent.”

“That’s not fair. Yes, I lived rent-free. But I’ve worked like a dog on this place. I’ve cleaned and scraped and sanded and painted. I’ve planted every single tree and shrub—”

“And it looks great. So what? Consider that sweat-equity your rent. I don’t care. It doesn’t change anything. This place is half mine, and I need my share!”

I hadn’t intended to get mad. I had meant to stay cool, to sit back and let her flail around on the hook of what’s-fair-is-fair. But just being in this house made me crazy. Decadent or painted up like an Easter egg, it didn’t matter. This place was a hellhole and I hated it. I wanted my money and I wanted out of here. The sooner Alice realized I was serious, the better.

So I leaned back in the chair and tried to calm my galloping pulse. “If you want the house, fine. I’ll take the back acreage and sell it.”

“But you can’t,” she muttered, head down again.

“Why the hell not?”

“Because…Because Lester and I…we built our church on it.”

I couldn’t help it. I started to laugh. “You built a church on it? On this foul piece of ground you built a church? That’s the church Daniel was talking about?”

“I’m not surprised that you’d laugh at a church.” Alice threw the words at me, rising from shame back into her comfort zone of righteous indignation.

“Oh, relax, will you? I’m not laughing at your precious church. Church or house, I don’t care, Zoe. All I want is what’s legally mine.”

“You don’t understand,” she said in a lower voice. “You can’t take the church because…”

I waited expectantly for whatever justification she would come up with.

“Because we sold the land it’s on to the church board. It belongs to them now.”

I wasn’t sure I heard her right. “You sold it? How could you have sold something that wasn’t yours to sell?”

“Everyone thought you were dead!”

“Everyone except you! You knew I was alive. You’d seen that video.” My rage boiled over, bone-deep and fire-hot. “You lied to get your hands on my inheritance. That’s illegal. That’s fraud. I could have you arrested.”

I pushed out of the chair and stormed to the back door. Then I whirled around and stared at her. She was scared. Good. She’d better be scared. “What did you do with the money? My money?”

She pressed her lips together. “Most of it went to fix up the house. And to build the church.”

“Okay. Fine. I’ll take the house then.”

“No, Zoe.” She stood up and reached a hand to me. “Please. This is my home. Daniel’s home.”

“No, it’s my home now—”

I broke off when the front door banged open. Someone stormed up the stairs. Daniel. Then Carl strode into the kitchen.

His frown turned into a scowl when he saw Alice and me facing off. “What’s going on?” He crossed to Alice. “You all right?”

Of course she immediately burst into tears.

I rolled my eyes. Alice didn’t like the way I used my sexuality to get what I wanted. But how were her phony tears and feminine helplessness any different? Naturally Carl leaped to her defense in the same way a hundred men had leaped to mine in the past. Rockers or preachers, they were all the same. They flexed their muscles, pounded their chests, leaped to the little lady’s defense and hoped like hell that would get them a free ticket into her pants.

I’d become very adept at using men yet keeping them out of my pants. I wondered if Alice was as adept at it. Or was she already sleeping with good ol’ Carl?

“What did you do to her?” he shouted at me.

“Caught her in a crime that could land her in jail,” I said. Then with a glib wave of my fingers, I waltzed out the back door. I didn’t slam it. That would only signal that I’d lost control, and I wasn’t about to let Alice and that creep ever think that. But boy, I wanted to slam it.

Instead I stood on the bottom step and made myself take deep, calming breaths. I stared at the sky. The sun had set and a half moon rose, skimming the tops of the pines. Down by the creek the frogs were calling back and forth, tempting any lady frogs within distance with their macho bluster. Were there no worthwhile males anywhere in the animal kingdom? Or were they all just swagger and smoke?

From upstairs I heard the sudden thump of hard-driving music. Nothing I recognized. I stepped into the yard and looked up at Daniel’s window, its drapes drawn tight against the night. How long till he, too, became an absolute asshole?

Then Tripod came galloping toward me, tongue lolling and tail whacking from side to side. “At least you love me,” I said, squatting down to rub his ears. “And I love you, you ugly, old thing. Looks like you’re the only one around here having a good time.”

He rewarded me with a slap of his tongue that my face only partially avoided. “Okay, okay.” Then he was off again, happy as I hadn’t ever seen him. I started after him, I guess because I didn’t really feel like being alone. He might be at home in the country, but I wasn’t. A condo in Miami was more my speed. Or Austin, Texas. Some place with a good music scene. But not L.A. or New York.

New Orleans would be perfect.

I shook my head against the thought. Too close to this place. Besides, what did I want with a good music scene? Certainly not a musician for a boyfriend. I was giving up the Red Vidrine lifestyle for a quieter, calmer one. Zoe Vidrine, soccer mom.

I stopped at the outer edges of the mowed yard and stared into the wild thicket that carpeted the woodlot, on down to the creek. Where I moved to would depend on how much money I could get from selling this place. All I needed was a nice little condo—two bedrooms—in a neighborhood with a good school.

With my left hand I made a slow circle over my deceptively flat stomach. “I’m doing this for you,” I whispered into the night. “So I can stay at home a couple of years and devote myself to you. We come from a long line of motherless women, but that’s going to change with you.” All I needed was a small home, a few writing gigs a month—music reviews, band interviews—and the two of us could get by.

The three of us, I amended when Tripod came crashing through the undergrowth, wet this time. “The three of us,” I said, fondling his ugly mug. “Come on, let’s go inside and get you your dinner, unless you’ve already eaten Angel.”

Though I didn’t want to deal with Alice and her other lapdog, Carl, no way was I letting them think they could intimidate me. Alice had cheated me out of a lot of money. She knew it and I wasn’t going to let her forget it. So I strode into the kitchen—only to find it empty.

Just as well.

I fed Tripod, all the while conscious of the heavy rhythm of Daniel’s music shuddering through the ceiling. I was up on all kinds of music, from hardcore punk to ambient noise, to hip hop, to grind core. But I didn’t recognize this band. As I started up the stairs, though, I got a brilliant idea. Daniel was fourteen or so, just coming into his own when it came to musical preferences. If I chatted him up about his music, it would probably piss the hell out of Alice. But it could also be the start of a great article: Tomorrow’s Music Connoisseurs—What They’re Listening To Today. Plus, I needed to learn how to relate to kids.

I knocked twice before Daniel cracked the door. He looked like a younger version of G.G. when he was in a foul mood. Lowered brow, downturned mouth.

“What?” he asked. I couldn’t hear the actual word due to the volume of his music, but I could read his lips.

I smiled. “I was wondering who that was. I don’t recognize the band.”

“What?”

“The band!” I shouted. “Who is it?”

“Oh.” He opened the door to let me in. Then he lowered the volume and handed me the CD cover. Power of Odd.

“Never heard of them. Are they local?”

“Sort of. One of them went to Covington High School and they’ve played at a couple of youth revivals.”

“Youth revivals? You mean they’re Christian rock?”

“Yeah.” He gestured me to sit on his bed, then picked up a handful of CDs for me to look though. As I checked them out I listened to Power of Odd. No reference to Jesus in the lyrics, at least not directly. No wonder I hadn’t pegged it. With the pounding drums—it sounded like a double set—and the howl of angst delivering the lyrics, it had more in common with Metallica or White Snake than what I thought of as saccharine church music. Debbie Boone it was not.

“These guys aren’t as fierce,” he said, as he reloaded the CD player with a different group. “More lyrical. Good for relaxing.”

“While Power of Odd is better for raging?”

He ducked his head and shrugged. “It’s been a weird day, you know?”

“Tell me about it.”

We listened to the beginning of the first song, about temptation and love and getting your strength from above.

“Why’d you come back here?” he asked me.

I straightened up. No way was I discussing this house and my half of Mom’s inheritance. “Doesn’t it make more sense to ask why I left?” Another bad subject but not quite so dangerous.

“Okay. Why’d you leave? How old were you, anyway?”

“Seventeen. And this place was nothing like it is now.” What a monumental understatement.

“You ran away?”

“Yep.”

“How come?”

I laughed. “My mother, of course. She was crazy. And cruel. And selfish.”

“Just like mine,” he muttered.

“Oh, no, buddy boy. No way. Your mother is nothing like our mom.”

“Oh, yeah? Well you never had to live with a religious fanatic who thinks you’re five years old!”

“That’s true,” I admitted. “But at least you know she loves you. Cares about you. My mother treated us like we were adults. We had to feed ourselves, clean ourselves, take care of the house and pets—and her while she was loaded, which was most of the time. It was up to us to keep this place functioning while a bunch of pothead dopers crashed here whenever they wanted to.”

He stared at me in shock. “Grandma was a drug user?”

He didn’t know? If Alice hadn’t told him that, it stood to reason that she would be furious when she found out I had. Digging up all our buried family secrets and baring them to the light.

But too bad. It was his family history, too.

I slid onto the floor, sat cross-legged on the rug and leaned toward him. “My mother—your grandmother—lost her father when she was five. He died in Korea. Her mom promptly had a nervous breakdown. That’s what they called it in those days. Anyway, my mother was raised here on the farm, for the most part by her grandparents, who were already old and devastated by the death of their only son. From the stories she used to tell, it seems like nobody really took control of her, and she grew up pretty wild. By the time your mother was born, both of the old folks had died. So it was just Mom and Alice out here on the farm and, later on, me.”

He was listening intently, chewing on one side of his lower lip. “Even though Mom’s last name was Blalock, Grandma never married my mom’s father, did she?”

“No.”

He nodded. “That’s what I figured. But Mom won’t ever talk about it.”

“It wasn’t easy for us, growing up around here.” Another understatement. “Back then Vidrine Farm was known as Hippie Heaven. You know, a commune.”

I could tell by his blank look that he didn’t know what I was talking about. I rolled my eyes. “Go to the library and check the local newspaper during the seventies and eighties. There are lots of articles about Caro Vidrine and the Vidrine Farm.”

“Maybe I will,” he said, frowning. “Once I’m not grounded anymore.”

“You’re grounded? Why?”

“They said I split for four hours without telling them where I was going. But I did tell them!”

“Yeah, I heard you.”

“And anyway, it’s not Carl’s place to ground me.”

“Carl grounded you?”

Daniel flung himself on his bed. “He thinks he’s my dad or something. But he’s not.”

I considered a long moment, then decided, so what if I was pumping the kid for information? “Are your mom and Carl, you know, a couple?”

He shot me an aggrieved look. “If you mean, like, are they getting married—” The rest was muffled when he slapped a pillow over his face and screamed into it.

I stared at him in shock. He was a strange mixture of polite kid and raging teenager. Homeschooled and protected but part of a sick family history of neglect and depravity. Self-control versus self-indulgence, that sure described me and my poor, uptight sister. And now Daniel was trapped in a new version of the same hellhole. Mom the drug addict; Alice the religion addict; and me the—

What?

What was my addiction? What made me feel safe and in control? Shopping? That was temporary. Adulation? Unfortunately that too was temporary, especially since I didn’t have enough talent as a model, actress or singer to make the big time.

So where did I turn for comfort? Certainly not to men. Men have their uses. But after my first disastrous love affair, I’ve never had any delusions about them.

My hand moved once more to my stomach, and that’s when it dawned on me. This child. I was banking on her—or him—to be my happiness.

I’d never wanted children. Certainly I’d been very careful to always use birth control. Always. But somehow I’d managed to conceive this child. And once I’d figured out why my breasts were so sore and my period was late, I’d become fixated on her.

Me, a mother.

I was determined to do it right, to do it as close to perfect as I could. That’s why I needed to get settled down in the right place and the sooner the better. My child would have the safest house and the best mother any child ever had. At least I hoped so.

Daniel sat up abruptly, startling me back to the moment. “How long are you staying here with us?”

“I’m not sure. Why?”

“What do you think of Carl?”

Now that was an interesting question. I decided to be honest. “He seems too old for Alice. And too rigid. And mean.”

He snorted. “Nice description of the man who’s trying to be the next pastor at our church.”

“You’re saying he wants to run the church and marry the former minister’s widow?”

“You got it.”

I tried to picture Carl married to my sister, to picture her crawling into bed with him, and felt a shudder rip right through me. “Do you think she loves him?”

He gave a hopeless shrug. “I don’t know. All I know is I don’t like him, and he’ll never be my dad.” He looked up at me. “Did you ever meet my dad?”

“No.” I shook my head. “Sorry.”

Again he shrugged. “So how come you were gone so long? Mom says it’s like, twenty-five years.”

“Twenty-three. And I left because I hated this house and everybody in it.”

He picked up his remote control, pointed it at the stereo and lowered the volume. Then he stared intently at me. “You hated my mom, too?”

I let out a long, slow breath. “When I left here…yeah. I hated her, too. I begged her to leave with me. I’d been begging her to leave ever since she turned eighteen. But she wouldn’t go.” Chicken-shit bitch. I managed a careless smile. “So one day I just took off on my own. But don’t you be getting any big ideas like that,” I added. “You’re only fourteen. And from what I can see, you’re not exactly in any danger here.”

“You were in danger? In your own house?”

I straightened up, stretched my legs out and flexed my ankles. “I thought I was. The kind of men who hung around here weren’t above hitting on a teenaged girl.”

He digested that a moment, then in a low voice asked, “What about my mom?”

“You mean, did they hit on her?” I thought back to those days, to how fat Alice was then, how frumpy and maternal. Meanwhile I’d been the leggy daughter, willowy and tall for her age, with an untamed head of fiery red hair—and a fiery temperament to match. To a certain sort of self-indulgent man, that’s like a signal light flashing “come and get it.”

“Alice had a way of discouraging dirty old men. Look,” I went on, needing to change the subject. “I doubt your mom wants you knowing all this sh—all this stuff. The reason I knocked on your door was to try out an idea on you.”

“An idea? On me? What do you mean?”

“I write articles for magazines, newspapers. Usually they’re interviews with musicians or music reviews. Stuff like that. Anyway, I was thinking about an article on kids your age—what they’re listening to, what they might be listening to in the future. Sort of a check-in with the young teen music-lover. And I thought I’d start off with you.”

He’d become somber during my description of the old days in this house. But the thought of being featured in a music article brought an eager smile back to his face. He swiped one hand through his sandy hair, leaving part of it sticking up straight. “Yeah. Sure. And I can hook you up with some of my friends, too.”

“Great. Do you know any online chat rooms with mostly young teenagers talking about music? I thought I could—What?”

His face had grown dour again. “I’m not allowed to go online for anything except school stuff. Especially not to chat rooms.”

“Okay. That’s okay,” I said, wondering how long Alice could choke him before he burst free. “I’ll figure that part out myself.”

“There’s one more thing,” he said, when I stood up.

Another question about his mom in this house, I figured as I braced myself. “Okay, what?”

“If I’m gonna help you with this article, well, I thought maybe you could help me with something in return.”

“If you mean putting in a good word for you with your mother, sorry, Daniel. I’m not exactly her most favorite person. If I asked her to go easy on you with this being grounded, it’s more likely she’d double your punishment.”

“No.” He shook his head and shoved his hands into the pockets of his jeans. “It’s not that.”

“Then what?”

His eyes narrowed. “I don’t want my mom to marry Carl.”

Uh-oh. Tricky territory. I shook my head. “There’s nothing I can do about that either.”

“I know you and Mom aren’t too cool with each other right now. But eventually you’ll straighten things out. I mean, you’re sisters. You can’t be mad at each other forever.”

Ah, the innocence of youth. “Maybe. Maybe not. But I know one thing, she won’t be asking me for any advice about men.”

He frowned. “All I’m asking is that you discourage her from marrying him. Is that so hard?”

“No. On the surface it’s not hard at all. But there’s so much going on beneath the surface here, Daniel, that I’m just afraid anything I try might backfire on you.”

“Well.” He plopped down on a blanket chest beneath the window. “Be subtle then.”

Subtle. Never my strong suit. But what could I say? Besides Alice, Daniel was my only living relative. “I’ll tell you what.” I stood up and sidled toward the door. “Let me think about it, okay?”

He hesitated, then nodded. “Okay.”

I would think about it, but in the end I was pretty sure the answer would be the same. No. And yet as I stared at him I felt the weirdest sensation, the strangest sort of affection for this kid that I’d only met today.

Not a rush of love or anything sickly sweet like that. Not a rush. But maybe…a trickle.

CHAPTER 4

I slept like G.G. used to when he was mixing drugs and alcohol: comatose for twelve hours straight, and I felt groggy when I woke up. A little clock ticked on the small, round table next to me, but I felt like it was shaking the whole bed. Then I realized that it was Tripod’s whiplike tail whacking the mattress in rhythm with the clock.

“Okay, okay,” I mumbled, squinting at the brightly lit window. Nearly eleven? No wonder Tripod was getting antsy. I rolled out of bed, found my same jeans and T-shirt—I really needed to unpack—then on bare feet headed downstairs. The house was quiet, and I could tell I was alone.

I saw a sticky note on the office door: “Leave Angel inside.” Sure enough, fluff-ball’s shrill yapping started up. Tripod’s ears perked up. Once he sniffed and snorted at her, however, only silence came from the other side of the door.

“What the hell,” I muttered, and opened the door.

I’ll give Angel credit; she was fast. Through the door, across the foyer and halfway up the stairs before Tripod could even turn around. There she stood her ground, ceding the first floor to Tripod but daring him to try for the second.

Tripod, of course, leaped joyously into the dare. But I caught him by the collar and dragged him to a standstill. “Cool it, mutt. Let’s go outside.”

Once we were on the porch, Angel ventured down, resuming her yapping at the front door. I figured the two of them would eventually sort things out. The real question was how I was going to sort things out with Alice.

One hour, one shower and one cup of coffee later I was on my way. There were a couple of lawyers in the several towns around here, but I worried that some of them might know Alice and her recently deceased minister husband. So I picked the sleaziest, most likely to be godless one I could. According to his yellow pages ad, Dick Manglin was just what I needed. Personal injury, criminal defense, DWIs and bail bond reductions. Someone whose only goal was to win, win, win.

I didn’t call for an appointment. I figured my snug-fitting dress, stiletto sandals, red toenails and redder lipstick would get me in.