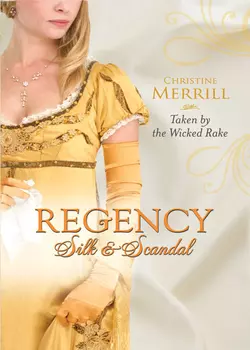

Taken by the Wicked Rake

Christine Merrill

“I hate you, Stephano Beshaley. As much as you hate my family. ” Lady Verity Carlow is poised, beautiful, charming, virginal. Her family’s precious jewel. She knows she will marry whatever titled bore is chosen for her. But sometimes, in the dark of the night, she wishes she wasn’t always so well-behaved. . .Then she is snatched! Kidnapped by her family’s enemy, gypsy lord Stephano Beshaley. And when this dark, dangerous unsuitable man takes Verity in his arms, he tempts her to do wicked, wicked things. And, shockingly, she does not want to be rescued – not one little bit!

London, 1814

A season of secrets, scandal and seduction in high society!

A darkly dangerous stranger is out for revenge, delivering a silken rope as his calling card. Through him, a long-forgotten past is stirred to life. The notorious events of 1794 which saw one man murdered and another hanged for the crime are brought into question. Was the culprit brought to justice or is there still a treacherous murderer at large?

As the murky waters of the past are disturbed, so is the Ton! Milliners and servants find love with rakish lords and proper ladies fall for rebellious outcasts, until finally the true murderer and spy is revealed.

REGENCY

Silk & Scandal

From glittering ballrooms to a smuggler’s cove in Cornwall, from the wilds of Scotland to a Romany camp and from the highest society to the lowest …

Don’t miss all eight books in this thrilling new series!

REGENCY

Silk & Scandal

A season of secrets, scandal and seduction in high society!

Volume 1—4th June 2010

The Lord and the Wayward Lady by Louise Allen

Volume 2—2nd July 2010

Paying the Virgin’s Price by Christine Merrill

Volume 3—6th August 2010

The Smuggler and the Society Bride by Julia Justiss

Volume 4—3rd September 2010

Claiming the Forbidden Bride by Gayle Wilson

8 VOLUMES IN ALL TO COLLECT!

www.millsandboon.co.uk

About the Author

CHRISTINE MERRILL lives on a farm in Wisconsin, USA, with her husband, two sons and too many pets—all of whom would like her to get off the computer so they can check their e-mail. She has worked by turns in theatre costuming, where she was paid to play with period ballgowns, and as a librarian, where she spent the day surrounded by books. Writing historical romance combines her love of good stories and fancy dress with her ability to stare out of the window and make stuff up.

REGENCY

Silk & Scandal

Taken by the Wicked Rake

Christine Merrill

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

To Annie, Gayle, Julia, Louise and Margaret, again.

And always. What a wild ride it’s been.

Chapter One

August, 1915, Warrenford Park

‘Are you enjoying the party, my dear?’ Robert Veryan, Viscount Keddinton, rocked back on his heels, as though proud of the job he had done in entertaining his only goddaughter. His wife, Felicity, stood on her other side, equally satisfied with their efforts.

Verity Carlow looked around the ballroom at Warrenford Park. The walls were a pristine white, the accents gold, the design classic and without the fussy Rococo that she had seen in some houses. The music playing in the background was sedate, and as clean and expertly rendered as the white walls. The dancers on the polished marble floor moved to the tune like clockwork figures, and the observers kept their chatter to a polite and unobtrusive level.

It was well-ordered perfection.

The sight of it made her head ache. She gave her host a brave smile that did not suit her mood and said, ‘It is a lovely evening. Thank you so much, Uncle Robert.’ He was no more her real uncle than this ball was a true entertainment. But if he wished to think himself so, it would be unkind to disappoint him or to complain that throwing her this party was little better than putting curtains over the bars of a cage.

She could not, for one minute, fool herself into thinking that this was a pleasant trip to the country. Her brother, Marcus, had made it clear that she was being sent to Keddinton’s country estate so that the family could more easily control her acquaintances and associations.

It was more than a little unfair of Marc to treat her so. In her twenty-one years, she had done nothing to give her family cause to worry. Her past was devoid of even the smallest misstep. But it did not matter to anyone what she had or had not done. When they had sent her into exile, her brothers cited unnamed predators and vague ‘risks to the family’ and promised that it was done for her own safety. But when she had asked for details, they had been unwilling to clarify their statements so that she might do anything to protect herself.

How could she know what to guard against, if no one would tell her the truth? When she asked who or what she needed to avoid, the best they would manage was a rueful shake of their heads, and the answer, ‘Everything.’ They had packed her off to the country, where she would be bored but safe. And there would be no getting ‘round Keddinton on the details of the trouble, or when it might be safe for her to return to London. Uncle Robert was the biggest spymaster in England. She might as well have tried to coax secrets out of the ballroom walls.

He was smiling at her now. And though his expression seemed harmless and friendly, she was sure his sharp grey eyes were as ever-watchful as a jailer’s. As if to confirm the fact, he said, ‘I promised your father that I would keep you safe. And so I shall. It is an honour and a privilege to do so. But it must have been difficult for you to leave your friends in town.’

‘It was no hardship to come here,’ she lied. ‘You know that I always enjoy our visits.’ Although she was not sure why he felt the need to watch over her so closely. If there were evil people who wished to harm her, did it not make more sense to find and cage them, instead of standing guard on her as though they expected her to instigate the problem through her own foolishness?

Lady Keddinton added her thoughts to her husband’s. ‘We want to make sure that you are not feeling blue. And we will give you opportunity to continue to socialize. For I know your family had hoped that, by now, you would have made a match.’

Verity looked at her hostess more closely. Was this an honest comment or just another quiet prod to make her choose from among the carefully vetted candidates in this room? She would think it was the latter, had not Aunt Felicity two unmarried daughters to dispose of.

Not that she wished to poach suitors from the Veryan girls. Verity had hoped that she might be free for a time from making any choice at all. She gave a firm nod of thanks and said, ‘There have been three weddings in the family within twelve months. We have had quite enough excitement, even without my help. I think it is probably better that I wait another Season to marry, if only to avoid further stress upon father.’

‘But it would not stress him at all,’ Uncle Robert said. ‘I know for a fact that he is most eager to see you settled.’

Before he dies. Why would he not just say the words aloud, for he was clearly thinking them?

Verity wished that she were allowed to curse, even in the silence of her own mind. To do it aloud would be even better. There were times when it would be most satisfying to tell everyone what she was really thinking. She would say that there was not a single man in London or the country that had raised in her the least desire for an association longer than a single dance. But everyone expected her to make a choice that would set the course of her entire life, so that her father could pass on, believing she was happy and settled.

Uncle Robert was still smiling. ‘Now that Alexander is home, you need not fear loneliness.’

‘I am sure you will find him good company. You played together quite charmingly when children.’ Aunt Felicity was smiling as if there was little left to arrange but a suitable date and the menu for a wedding breakfast.

Although she worked very hard to retain control of her emotions, Verity could not marshal the small sigh that escaped her, on the mention of the Veryans’ son. She remembered him not as a good playfellow, but as a miserable little toad. Their recent meetings had done nothing to change her opinion of him. If the true reason for this visit was to isolate her from London Society to put the good character of Alexander Veryan in sharper relief, then she would make her brothers pay dearly for the trick.

Especially since, once they chose to marry, everyone around her had paired off in record time with people that would be considered far too unsuitable for her. Though his bride, Nell, was the sweetest girl in the world, Marcus had married beneath his station. Her sister, Honoria, had admitted in a particularly unguarded letter, that her new husband had only recently stopped smuggling and found honest trade. Even Diana Price, who had been a paragon of virtue while she had chaperoned the Carlow girls, had thrown propriety aside to marry the gambler Nathan Wardale.

Of course, brother Hal’s wife, Julia, was beyond reproach. But since Hal himself was incorrigible, his choosing such a worthy bride had been as surprising as the others’ selections.

It was clear that each of the matches had been made on the basis of an almost overpowering attraction. The parties involved had been swept away by their feelings, and had given over to actions that were most unlike their usual behaviour.

Then they had all turned to Verity, thinking that for her it would be different. She was to be the sensible one and listen to the wise counsel of people who were happy enough to ignore their own advice. She was expected to barter herself away to someone like Alexander Veryan, making a minimum of bother to her family. Everyone could then go back to their adoring spouses, secure in the knowledge that it was someone else’s job to worry about little Verity’s future happiness.

‘And here is Alexander, now.’ Lady Keddinton smiled with such pride at the approach of her son that he might as well have been Lord Wellington in full dress uniform. But all Verity saw was a young man graced with deficiencies in height and colouring, whose grey Veryan eyes seemed watery and cold in his pale face.

‘Verity.’ He bowed to her and reached for her hand before she could offer it. His own was soft and damp.

‘Alexander.’ Why could she not stop smiling, even when cool indifference was needed? Mother’s obsessive insistence that she be graceful and charming in all situations was no aid in putting off this most persistent of young men.

‘Are you free for the next dance?’

She glanced at the musicians, who were running through the first notes of a quadrille. Saying yes now would allow her to beg off later, should the dance master call for a waltz, or some other dance that required prolonged physical contact with her partner. She smiled again. ‘Of course, Alexander.’ She allowed him to keep her hand as he led her to the floor, hoping that he did not equate simple courtesy with a desire on her part for increased intimacy.

They formed up with three other couples to begin the intricate steps of the dance. And immediately, her pulse quickened and her fears of a sensible future with Alexander dissolved. She was looking across the square into the eyes of the most fascinating man she’d ever seen. The eyes in question were large and dark, liquid and bottomless, fringed with long black lashes, and set in an olive-skinned face. The man’s nose was straight, and his full lips curved in the faintest of smiles as he looked across at her, returning her admiration.

She walked around him, following the dance. It gave her an opportunity to admire the cut of his coat. He was almost too well dressed, his clothes narrowly missing foppishness, just as his face on another man might have been feminine. The darkness of his skin made his cravat and shirt seem blindingly white, and his deep blue coat was as soft and dark as the night.

There was a glint of silver at his wrist, when he reached for her hand, as though his shirt cuff concealed some bit of jewellery. What an unusual thing it was, to see a man ornamented in such a way. If she had truly seen a bracelet, there must be some story attached to it. Looking at the man, she was sure that the tale would be both exciting and romantic, and that she would very much enjoy hearing it.

The touch of his hand was warm and dry, and full of interesting roughness. She wondered just what he had been doing to cause those imperfections. Riding? Duelling? Or was he adept at some art or science that she knew nothing of? In any case, he was gentle to her, and the friction of skin against skin was delicate and exciting.

She returned with reluctance to her own partner, and he caught her hand again in his disappointingly moist grip.

So went the dance, with a series of brief and inviting touches from the gentleman opposite her that made poor Alexander suffer by comparison.

Through it all, the dark stranger smiled at her. There was no mistaking his interest. He was looking at her with curiosity and a bit of sympathy, as though he wondered how she came to be matched with the man beside her. And was she mistaking it, or was there longing there, as well? If she read the truth on his face, he wished he had been partnering her instead of the woman at his side. That woman was receiving only polite attention from him, much to her obvious chagrin.

Verity smiled back at him, wishing she had a fan to hide her blush and covertly signal her interest. If Lady Keddinton would allow an introduction, she was sure that he would turn out to be a horrible rake. He looked like just the sort of man that Diana would have singled out as the worst in the room.

And the hint of a sparkle in his eyes told her that he could see how he was affecting her. For all her previous and undesired poise, she could find no way to disguise her reaction to the stranger.

Verity felt another pang of loneliness. She needed the guidance of Diana and Honoria. Either of them would have prevented her from doing what she longed to do right now. Diana would have cautioned her against it. And Honoria would have very likely done it in her stead. But as Verity looked at the dark man, she felt the undeniable tug of curiosity. She wanted to talk to him.

When the dance ended, she asked Alexander to return her to Aunt Felicity, and go to fetch a lemonade. Once he was out of earshot, she asked Lady Keddinton, ‘Who is that man, standing there, by the musicians?’ She held her breath, taken by the sudden fear that he was an uninvited guest. Suppose he was the stranger she had been warned about, and his interest in her sprung from a desire to do her harm?

Lady Keddinton, who was many years married and far too sensible to do such a thing, blushed like a schoolgirl. ‘That is Lord Salterton. He is …’ She paused for a moment, as though trying to remember how she had come to invite someone more interesting than Alexander to Verity’s party. ‘A friend of my husband’s, I believe.’ She glanced around, seeking Uncle Robert’s agreement, but he was deep in conversation on the other side of the room. She returned her attention to the man they had been discussing. ‘He is recently returned to London, having travelled in the Orient.’ She gave the smallest sigh. ‘A most fascinating gentleman.’

Verity’s fears subsided. He could have no part in the family’s recent troubles, if he had been in the Orient when they happened. She gave a small, envious sigh. If she asked, would he share stories of his adventures? After looking into his eyes, she was sure that he had seen things that were wonderful, horrible and far more exciting than anything found in her limited experience. ‘It must be very educational to be so widely travelled. May I …’ Verity paused, trying not to appear too eager. ‘… May I be introduced to him? Or would that be too forward?’

Her hostess hesitated, as though trying to find a logical reason to separate the guest of honour from one of the guests brought to honour her.

But the gentleman in question settled the matter for them. He was making his way across the room towards them, moving with a dancer’s grace as though he was walking in time to the music. He bowed slightly to his hostess, and favoured her with a smile that made the old lady’s face turn an even more shocking shade of pink. ‘Lady Keddinton, such a lovely evening. It is good to be warmly welcomed, after such a long time away from England.’

His voice was low and smooth, and as captivating as his person. He spoke precisely and with a faint unidentifiable accent, as though English was his second language and not his first. Verity drank in each word. She studied the man as minutely as courtesy would allow, fearing that she would not get another chance. Once Aunt Felicity noticed her interest, she would be sure to send Lord Salterton away. And then Verity would never know if the small scar upon the lobe of his ear was because it had been pierced to hold a ring.

Now he was turning to look at Verity again. She dropped her eyes quickly so that he would not catch her staring. ‘And I must say the company is charming, as well. I beg you, do me the honour of presenting me to your friend, for I have few acquaintances here and wish that were not the case.’

He wished to meet her? Now it took all her control to maintain the thin veneer of polite interest that hid her true desires from Aunt Felicity. It would be a bitter disappointment if her instant attraction to the gentleman prevented his invitation to future gatherings.

Lady Keddinton’s smile turned frosty. She could not very well cut the man, when he was being so perfectly civil. ‘Lady Verity Carlow, may I present Lord Stephen Salterton.’

When the turn came for her to speak, her poise failed her and Verity stammered as though she were just out of the schoolroom.

And Lord Salterton was polite enough to pretend he did not notice the fact. He said, ‘Would you do me the honour of another dance, Lady Verity?’

She thought again of her brother’s warning, and felt quite ridiculous for it. It was not even a waltz, and she was in a public place with a man that her hostess knew well enough to introduce. Dancing with Lord Salterton hardly fell under the class of associating with strangers. It would be no more forward than dancing with Alexander had been, and considerably more pleasant. ‘Certainly, sir.’

He offered her his arm, and led her out onto the floor. It was amazing that something so simple could be so affecting. She had walked thus with him in the quadrille. But not as his partner. Now it was as if he had claimed her for his own. As they moved through the form of the dance, she was barely aware of the others in the room with her, only the man at her side. Perhaps it was because he did not speak. In a less skilled dancer, she would have suspected that he required full attention for counting the steps. But this man seemed to be focusing solely upon her, watching her as she moved, gazing into her eyes as they met and turned. And he sighed ever so slightly, each time they parted. Was he too shy to speak? She did not think so. There had been nothing in his gaze to indicate the fact, as she had watched him.

But his reticence made her want to draw nearer.

‘It is a lovely evening, is it not?’ She spoke to fill the silence between them, and felt incredibly gauche for it. Could she not have come up with something more interesting to say to a man that had been everywhere? Although what about her could possibly entertain a man so worldly, she had no—

‘Yes. Delightful.’ He looked straight at her as he said it, so she was sure that the comment was intended as a compliment to her and had nothing at all to do with the dance.

‘Thank you.’ And that had been a remarkably stupid response. If he’d meant anything other than what she assumed, it would have made no sense at all.

His lips twitched a little. He knew exactly what she’d thought, and her answer amused him. ‘You’re most welcome.’

Welcome to do what? His response had proved her perceptions were correct. And now, though he appeared to answer her in kind, he had included an invitation to something, she was sure. He wanted something from her. Or wanted her to want something from him. Or he meant something else entirely that she did not understand.

Oh, how she wished Diana was here to explain. Although it was probably best that she was not. Diana would have glared from across the room, dismissed him with a snap of her fan, and packed Verity off to home before either of them could manage another cryptic exchange.

He gave another smile and an exasperated sigh, as if to say, ‘You are not particularly skilled at flirtation, so I shall be forced to help you.’

And then, he said aloud, ‘It is a lovely night. But it is most oppressive in the ballroom. Perhaps a turn around the garden would be pleasant.’ He spoke the words with such deliberate slowness, that she was sure he meant.

Where I mean to kiss you senseless, as soon as we are out of sight of the house.

‘No,’ she said, suddenly and firmly. ‘I do not think that would be wise at all. I do not like gardens.’ Which was not only untrue, but another exceptionally odd statement.

‘You do not like gardens?’ He smiled again, as though her attempted set down were but another joke. ‘Perhaps it is because you have not seen them in the moonlight.’

Or with the right company.

That was what he meant. She was sure of it. For all his good looks and attractively chosen words, he was the sort of man who expected a tryst in the garden after a single dance, and he was vain enough to assume she would throw off the strictures of Society for an opportunity to be alone with him.

‘On the contrary. I am not so foolish as to think that what appeals to me in moonlight will have the same charm when the sun rises. Now, if you will excuse me.’ And she walked away and left him on the dance floor.

She hurried to the ladies’ retiring room, one hand to her face, feeling the growing warmth of her cheeks. She’d made a cake of herself in front of everyone by walking away from the most desirable man in the room, in the middle of a set.

Which was not to say she desired him, of course. Or that she secretly wished to go out in the garden and see if her suspicions about him were correct. Because, if conversation had turned immediately to horticulture, she would not have been able to contain her disappointment.

No. No. No. She was not to go off with strangers. And even if he was a friend, she did not wish a compromising situation in the garden with him. She was not even sure she wished to marry at all. Men were a bother, and it would be just as easy to go through life alone than to adjust one’s habits to suit.

Of course, it was doubtful that what he was offering had anything to do with marriage. Merely the most pleasant type of dalliance. One might go out into the garden with one such as Lord Stephen Salterton, and come back a changed woman. And no one need be the wiser.

She put a hand to her temple, as though she could push the thoughts back out of her head. With a few words and half a dance, the man had put ideas there that she could have gone a lifetime without thinking. It was a very good thing that she had not gone outside with him, for it would have been the first step on the road to ruin.

She glanced around herself, relieved to see that she was alone in the room. It was early in the evening, and there was little need for the other female guests to be hiding away with fatigue, either real or pretended. She would take a few moments to compose herself, and then return to the party. Another turn around the dance floor with Alexander would chill any romantic notions in her head. And she would never again speak to the upsetting Lord Salterton.

But just to be on the safe side, she would stay away from the garden doors.

She glanced in the mirror, straightening hair that did not need straightening, and smoothing skirts that were already in place. If one took sufficient care with one’s appearance—and did not get overheated by a few simple dances—it was hardly necessary to fuss further. It was not as if a brief conversation with a man was as strenuous as a tussle in the bushes.

And now, she was thinking of tussling, and bushes and gardens. And Lord Stephen Salterton. And her cheeks were growing pink again.

Diana had warned her of the dangers of feelings such as these, and of the need to repress them at all costs. While men might think such things about even the gentlest of young ladies, it did not do for young ladies to emulate their coarse behaviour.

She took a few deep breaths and made her mind a blank so that she might return herself to something akin to normal. And then she stepped from the room.

As soon as she was clear of the door, arms seized her from behind, and a hand covered her mouth, stuffing a rag between her teeth to muffle her attempt at a scream.

Chapter Two

Her assailant wrapped her round about with a piece of rope, firmly pinning her arms to her sides until it was difficult to stand without his help. Then he began to push her toward the back door of the house, and into the very gardens she had planned to avoid.

She stumbled and kicked against him, trying to bump into walls in an effort to shake free of him and stop his progress. But her struggles had no effect. He had a firm grip on the ropes around her body and kept her upright, pivoting easily as she fought to throw him off balance. When he spoke, his voice was barely winded, as though the effort to contain her were no more difficult than walking alone. ‘This would have been simpler if you had gone into the garden when I asked. But you are not as easy to gull as the rest of your family. Now, we must do it the hard way. Cease your fighting, for it will accomplish nothing. I am much stronger, and I have no wish to prove that fact by striking you.’

She had imagined that the man who grabbed her must be some ruffian or stranger who had wandered into the house through an open back door. But the man whispering into her ear made no effort to hide the exotic cadence of his voice. It was Lord Stephen Salterton who held her. To be so used by an apparent gentleman was the last thing she had expected. Could he have been the one that had been the reason for all of Marc’s vague and dreadful warnings, after all?

She responded by fighting harder, her hands forming claws where they were trapped at her sides. But Salterton continued propelling her forward and out of the house. Why was there not a servant, a footman, someone or anyone who could stop this progress with a scream or a shout? The way before them was clear; it seemed that her abductor had known it would be so. He had planned his assault for a time when he would not be interrupted. He had known where she would go when he angered her. He had hidden a rope and the gag, so that he might quickly render her helpless. He knew how to get her out of the house and away.

There was nothing random or careless in the actions of this man. If he could slip under the guard of Robert Veryan to accomplish what he had, he must be even more dangerous than Marc had imagined.

Once clear of the house, he hoisted her off the ground and carried her into the night, running easily through the trees as though he could see in the darkness as well as in the light. Then he stopped and released her. And although she could barely stand unsupported, he was spinning her round and round on her feet until she was dizzy. When he stopped, she was no longer sure which way she should run to regain the safety of the house, even if she could manage it. Before she could find her balance again, he had gotten a sack from a hiding place behind a nearby tree and pulled it over her upper body. She could feel him binding it with more rope, tangling it around her skirts until her legs were trapped, immobile.

Then he scooped her up in his arms again, and went further into the trees. She could hear the crunch of leaves under his feet and feel branches slapping and tugging at her body as he ran. And then, she heard the sound of a horse snorting impatiently, and the creak of leather harnesses and wooden wheels. He lifted her further from the ground, and then dropped her none too gently onto the floor of a wagon or carriage. She felt the body tip as he leapt into the driver’s seat, and heard him snapping the reins and murmuring to the horse in a foreign language, which made it start forward at a brisk pace.

For a moment, she was frozen with the fear of what had happened. And then, she struggled to master her mind. Even though she could not use her eyes or her voice, she still had her ears. What else could she learn from them?

She was alone with this man. She’d heard no other voice offering to help him as he had loaded her into the wagon, nor had it seemed that there was anyone else involved in her capture, other than Salterton himself. No matter what his intent towards her person, as long as they were moving, he was busy driving. Nothing worse was likely to happen to her than had already. It was only when the wagon stopped that she would have anything to fear.

This fact provided some comfort and made it easier to control her panic. She had time in which to form a plan to thwart him. If he truly was a gentleman, then perhaps this abduction was something more than the coarse violation she had at first expected. Perhaps he only wanted ransom, for she could not think what she might have done to offend the man that would drive him to violence.

She tested her bonds and was sure, from the feel of them, that she was not strong enough to break them. But either he had overestimated her size in the voluminous gown, or had spared some small feeling to her femininity. The ropes were not as tight as she would have made them, had she been trying to subdue him. She wiggled her arm inside the sleeve of the dress.

She could manage only a small movement, but it was better than nothing. She smiled to herself, and set to work pressing her hand tight to her side, and wiggling it out from under first one loop, and then the next, working the coils of rope down her body. As her first arm came free, the bonds became looser still, and she found she could move the other arm. If both were untied, then perhaps her legs.

She shifted and stretched against the bonds. Their increasing slackness let her grip the inside of the sack, and work the fabric of it up and out of her way. If she could move it to a place where she might throw it off along with the rest of the ropes, when the wagon stopped she would kick free of the bonds and run. Who knew what he might do if he caught her? But she doubted it would be worse than what would happen if she went passively to her fate.

At last, she felt the horse stop, and heard the driver get out. But instead of coming to pull her out, he had gone to the other side of the wagon, as though he had forgotten her existence.

As soon as she was sure he was out of arm’s length, she wiggled free of the last of the ropes and tried to throw herself out of the carriage. There was a loud, ripping noise as her dress caught on a rough bit of wood. Then her petticoat tore from hem to waist, and she tumbled out and into the mud of the road. She scrabbled for purchase, slipping, falling, and then standing to run a few unsteady paces as the feeling returned to her legs. After the darkness inside the sack, the night seemed as bright as day. The landscape was unfamiliar. She did not know if there would be rescue ahead. But anywhere might do, as long as it was far away from her captor.

She heard a curse from the other side of the wagon, and the sound of Salterton coming after her. The ground was wet from a recent rain, and the heavy clay sucked one of the slippers from her feet, leaving her to run unsteadily in her stocking and remaining shoe. The puddles soaked her skirts, and the silk gown which had seemed so light on the dance floor, grew heavy and clung to her legs, making it even more difficult to run. She stepped on a flint, feeling the point of it rip through her stocking and poke into the soft flesh of her sole.

She had made it barely fifty feet when he caught her. He was annoyingly clean, having taken the time to pick his way slowly on the higher and drier ground, while she had blundered through the worst of the mud. He glanced down at her, where she had fallen again, wet and dejected at his feet. ‘Are you quite through?’

Truth be told, she was. It was clear that she would not escape him shoeless and with no idea of her location or destination. But all the same, she made another lunge away from him.

He caught her by the last bit of rope still trailing from her waist, and pulled her back as easily as if he was controlling a dog on a lead.

She turned and struck out, scratching at his face.

He swore and gave a shove, pushing her down on her back in the mud. The impact jarred through her, causing more shock than damage. Then he yanked her upright, until her face was close to his own. ‘I have no desire to do that again. But if you persist in that behaviour, I will take whatever steps are necessary to subdue you. Do you understand?’

She opened her mouth, trying to scream at him from around the gag, and reached to remove it. But he caught her hands to stop her, smiling at her efforts. ‘A nod will be sufficient. I have no intention of unmuzzling you until I am sure that you will not bite. And as for screaming to attract attention? I have taken you to a place so remote that no one will hear you, even if you cry out.’

At his words, the reality of her situation struck her again. She was very much alone, in a strange place with a strange man. He was smiling at her, but there was no warmth or friendship in his face. His look said that he would stop at nothing to get what he wanted. And for whatever reason, he wanted her.

After her fall, the soft net of her evening gown was soaking wet, clinging to her skin in ways that revealed more than she would have liked. The cold night air cut through it, making her shiver. But Salterton stood close enough to her that she could feel the heat of his body, and his hands were warm and dry, just as she remembered them from the ballroom. His grip on her wrists was not gentle, but neither did it hurt her. And for a moment, her mind tricked her into thinking it was not for restraint, but out of possessiveness that he held her, as though this touch was a shared pleasure—the first of many. And then, she remembered it for what it was, and struggled against him.

It did her no good. He was so solid and still that it was like fighting against a statue. At last, he grew tired of it, and said, ‘You strike me as being smart enough not to expend effort to no purpose. Your attempt at escape and your pitiful cat scratching is more amusing than anything else. Let me give you a word of advice. If you cooperate with me and give me no more trouble, you will be returned undamaged to the arms of your family. But if you resist, that may not be the case.’

She went still, as well, turning her rage inward to calm her body and her mind. As he had done before, he’d seemed to speak to her without words. He still smiled at her, but there was something, a hint in the darkness of his eyes that said, I am not as unmoved by you as I appear. Do not tempt me. And do not try my patience.

As if to confirm her fears, he raked her body with a slow, interested gaze, lingering in ways that no gentleman should linger. Then, he released her wrists and held out a hand, as if he were a gentleman, offering to help her back to the wagon.

She gave another little shiver, as though she could shake his eyes from off her form, and tried to loosen the wet cloth where it clung. Then she ignored his outstretched hand, walking with difficulty, for the torn fabric of her dress bunched and tangled around her legs.

He shrugged and grabbed the rope at her waist, giving a sharp tug on it as if to remind her who was in control. Then, with no further offers of help, he led her back to the wagon, returned to his place in the driver’s seat and waited for her to climb in beside him.

She glared at him, for he must know that she could not get up onto the seat without his help.

‘You seemed eager enough to manage before. I could help you. Or I could tie your leash to the backboard and let you run along behind. Or shall I leave you here, just as you are? You could congratulate yourself on the success of your escape. And if you are lucky, you might be found and rescued before you die of exposure.’

She dropped her gaze and waited for him to decide what he wished to do, unwilling to show any sign that he might take for weakness or cooperation. At last, he reached out and pulled her up to sit beside him. Then he retied the rope about her, binding her arms again and tying the other end to his wrist.

‘This is much friendlier, is it not? And so much easier to prevent further attempts to leave me. He gave the rope around her waist a small tug to tighten the knot. ‘You may struggle as you wish. It will not break. And it will not cut your tender English skin. It is silk. The same rope that hung the Earl of Leybourne, when your father let him die for a murder he did not commit.’

Was this what it was about? The Earl of Leybourne? Was Salterton some kin of his? She had met William Wardale’s children, and none were anything like this man. She had meant to shower him in a tirade of abuse, behind the muffle of the gag in her mouth. But all she could manage was puzzled silence.

He was staring at her, awaiting a response. And then he laughed out loud. ‘If you could see the look on your face. It is most amusing. I will remove the gag now, so that you may argue with me as you wish to. You will tell me that your father is innocent. That you think I am a villain. And that I shall pay dearly for this dishonour to you. I have had business with your family before, and I have come through it all with a whole skin. Though you rant and rail, it shall be the same again, I am sure.’

He reached over and yanked down her gag, pulling the handkerchief out of her mouth, and tossing it into her lap. She glanced down to see, in some relief, that the thing had been clean before he’d forced it upon her. And there, in the corner, the initials S and H.

He nudged her. ‘Go ahead. What have you to say for yourself?’

‘Stephen Hebden?’ Despite her family’s attempts to keep her in the dark, she had heard his name.

She knew she had guessed correctly, for he started a little as she called him by his real name. And then, he collected himself and returned to taunting her. ‘Some call me that. You may think of me as Stephano Beshaley, bastard son of Kit Hebden and Jaelle the Gypsy.’

So this was the man that her brothers had been warning her about. And she had fallen easily into his clutches, just as they had feared. It annoyed her that she had proved herself to be the naïve girl everyone thought her to be. If she had any wit at all, she would need to use it to escape from this situation, for the man at her side was smarter than she had given him credit. She stared at him, trying to divine his true character and wondering how she might separate reality from facade. ‘Your half sister Imogen told me of you. You are the Gypsy child that Amanda Hebden raised as her own.’

He rocked back in his seat as though a simple statement of fact bothered him more than the abuse he was expecting. ‘I am no longer a child. And I do not consider a few years of room and board to indicate any maternal devotion on the part of Hebden’s gadji wife.’ Hebden’s eyes blazed with a cold merciless light. ‘After my father was no longer alive to protect me, my stepmother and her family could not get rid of me fast enough.’

Was that pride in his voice, that his father’s family could not hold him? Or had their rejection hurt him? Because she could not believe that the feud between the families was all the result of a little boy’s injured feelings. She hazarded a guess. ‘If you did not like them, and they did not like you, then it was probably for the best that they sent you back to your mother and her people.’

‘Sent me to my mother’s people?’ He snorted. ‘They sent me to a foundling home and forgot all about me. When the Gypsies offered me a place, I returned to them with pride. And the Rom are not—’ his sneer deepened ‘—my mother’s people. They are my people, now. And they accepted me, even though I was a half-breed gaujo, whose mother was not alive to plead for my admittance to the tribe.’

‘Your mother had died, as well?’ she asked.

‘Of grief. Because the Hebden family did not want me, but neither would they return me to her.’

Sympathy blotted the anger she felt with him. ‘I am sorry.’

For a moment, he seemed genuinely puzzled by her response. ‘Sorry? Why should you be sorry?’

‘Why should I not be? It is a sad story. You and your mother were both badly served. Because I am only a girl, I have no say in the actions of my family. There is little I can do for you, other than to offer my sympathy for your loss.’

She prayed that he understood the fact, and agreed with her. For by the way he had been staring at her, the fact that she was an innocent girl had everything to do with the reason he had taken her. And she feared that he would demand far more than an apology, before the evening was through. ‘I am without value to you. Truly. But my father is rich, and powerful,’ she blurted.

‘I know who your father is.’ He smiled as though he had been waiting for the chance to reveal the extent of his knowledge. ‘George Carlow. Earl of Narborough. Betrayer of William Wardale. And true murderer of my father, Christopher Hebden.’

‘My father a murderer? You are insane!’ Any plan to reason her way to freedom was destroyed. But she could not let such an outrageous lie stand unchallenged.

‘Ha!’ he shouted back, as though he was satisfied with the revelation of her true nature, and twitched the reins to speed the horse. ‘My mother died with a curse on her lips for both the Carlows and the Wardales. Twenty years later, the Wardale children are thriving, and George Carlow sickens and dies.’

‘He sickens because he is old. Your continual harassment of my family is what weakens him. And he is not dying,’ she said, feeling the rising panic that had come so often in these past months. Because he could not be dying. Not now, when she was far from home and unable to be with him. ‘But you are trying to drive him into the grave, even though he has done nothing wrong.’

‘At best, your father was a meddling fool with no love for me or my family. At worst, he was a murderer. Soon, I will know the truth. Then the man who really killed my father will pay for his crime.’ He wrapped the rope around his hand and tugged it tight. ‘I will not bother with silk, or take the time to be gentle.’ And in that moment, he looked capable of murder.

‘But I had nothing to do with this. I was a baby when it happened. Let me go, and I will tell him what you said.’ Her voice sounded weak, pitiful. She struggled to control it so that he would not hear her fear and use it against her.

‘The children will pay for the sins of their fathers,’ he intoned, as though reciting scripture. ‘By my mother’s curse, you bear the guilt of your family. If your father wishes to stay my hand against you, he will admit what he did.’

She wished that she could raise her arms, so that she could put her hands to her ears and block out the man’s madness. If a twenty-year-old grievance and a dead woman’s curse had driven him to take her, then what hope did she have that he would be satisfied and release her, even if her father told him the lie he wished to hear?

She looked ahead of the wagon, trying to guess where they might be going. The road had narrowed before them. And now, there were overarching trees to block out the stars. She wished she knew enough about such things to guess which direction they had gone. Although she suspected that the glow on her left might be the first light of dawn. They had been travelling for hours, and she had not seen so much as a cottage.

Then, in front of her, another faint glow. She sniffed the wind. Wood fires. A horse gave a welcoming whinny as they drew near. They passed another bend in the road. And there before them, in a clearing surrounded by beeches, was a Gypsy camp.

She had never seen such a place before, but it must be that. There was a circle of tents, some of them big enough for a whole family, and also several curved roofed wagons that looked like small houses on wheels. But it was too early for the people to be awake. No lanterns were lit, and the cooking fires were banked. If she cried out, would anyone wake to help her? Or would they lie still in the dark, pretending that they did not hear?

The man who called himself Stephano Beshaley had driven close to the largest of the wagons, this one painted in green and gold. He slid out of the seat beside her, still holding the rope that bound her waist and hands. He tugged until she followed him to the ground, catching her as she almost fell. And then, he was pulling her towards the brightly painted wagon.

She set her feet in the ground and wrapped her hands on the rope, pulling back to free herself. ‘No.’

He laughed, and tugged back until she stumbled forward, into his arms. He held her, wrapping his arms about her waist, until there was no space left between them. ‘You will say yes to me, until I say otherwise.’

‘I will not,’ she shouted. But his touch made her feel so strange that suddenly she was not sure what would happen if he did not release her. ‘Let me go!’ She squirmed and pushed at his arms, trying to get away, but only succeeded in tearing a hole in her bodice when the net caught on the buttons of his coat. ‘Help me! Someone! Please!’

There was a grumbling from one of the tents, followed by laughter from another, and a child’s murmuring of questions, which were quickly silenced. But no one appeared, neither to aid her, nor to be curious about the goings on.

Her shouts made him hold her all the tighter, as though he meant to squeeze the air from her lungs. Perhaps that was what was happening, for she felt lightheaded, almost to the point of faintness. The contact of their bodies was more terrifyingly intimate than anything she’d experienced. But the fear she felt was not for the man who held her, but of the other more pleasant sensations he evoked. With a final shudder, she forced herself to stop fighting and lie still in his arms. For when she moved her body against the hardness of his, she could not remember why she wished to escape.

He must have felt it, as well, for he stood very still, and his eyes seemed to go even darker. He was staring at her lips as though he could know the taste of them, just by looking. And for a moment, she thought the same. For though he had not moved, she could imagine the feel of his mouth on hers, kissing her with such force that she would beg to surrender to him.

He moved suddenly, scooping her legs out from under her and carrying her up the little wooden steps of the wagon. He fumbled with the latch for a moment, then took her through and kicked the door shut behind them. It was too dark to see, but he had dropped her onto something soft that felt like a mattress.

She lay still, sure that any movement would draw dangerous attention from him. She should have thrown herself out of the wagon—to her death if necessary—instead of listening to his bitter childhood stories. Now, he was standing between her and the door, fumbling to light a candle. If she tried to push past him, she could not help but touch him. And if she touched him …

She was shaking, now. She told herself that it was only because she was cold and wet from her struggles in the bog. But she knew it was more than that. He was reaching for her.

And she closed her eyes and trembled with anticipation.

She felt his hands at her waist, untying the rope that was still attached there, drawing it out from under her body, and casting it away.

When she looked up at him, he was staring down at her, his own face devoid of emotion. ‘Strip.’

‘I beg your pardon?’ She scooted away from him on the bed.

‘Remove your clothing. To the last stitch. And then wash yourself.’

‘I will do no such thing.’

‘You will do as I say.’ He rubbed his thumb across his own dark skin, and then held it out to show her that is was clean. ‘You think me a dirty Gypsy? This does not wash off. But you?’

He reached for her, and she flinched away from him. But he caught her under the jaw and held her face still, running his other thumb slowly along her cheek. Then he held it out to show her the mud. ‘You are filthy. And you are sitting on my bed. Your fancy dress is ruined, and as useless in a Gypsy camp as the woman it covers. Remove your clothing and wash yourself, or I will do it for you.’

Then he turned away from her, going to a trunk in the corner. He began removing his own clothes, stripping off coat and waistcoat, cravat and shirt, brushing away the dried mud from them and folding each piece and putting it on a chair in front of him. When he stood bare to the waist, he splashed himself with water from the basin, and towelled dry.

Although she tried not to stare, it was almost impossible to look away. His body was lithe and his dark skin marked with a crisscross of scars. His shoulders were wide and strong, and she shivered as she saw the sinewy arms that had held her. The silver bracelet on his wrist almost seemed to glow against the darkness of his skin.

Then he pulled off his boots and trousers, and continued to wash. She could see the long line of his well-muscled flank. The curves and planes of his body were as well defined as a Greek statue—and every bit as bare. And he was as casual in his nakedness as the statue might have been, for he paid no more attention to her, as if he was alone in the room.

As she watched him, her insides gave a funny lurch and her heart beat unsteadily in her chest. It must be the result of too much fear and not enough food or sleep, and the stress of not knowing what might happen to her in the coming hours. If he was not watching, and she could not manage the strength to escape, she should at least gather the energy to protest this most recent threat to her honour. She should not be sitting on the bed in a daze, thinking things that did not match with what she ought to be feeling, in her current and extremely precarious condition.

She should not be staring.

Perhaps it was the disinterest he was showing her, at the moment when she expected him to be the most threatening. But she was overcome with a languor, and the desire to lie back on the bed and continue to gaze upon him. For he was beautiful in his nakedness, and totally alien from anything or anyone she had known.

He began to dress again, pulling on a pair of loose wool trousers, low boots, and a shirt of striped silk. Then he reached into a pouch at his waist and removed a gold hoop, fixing it in the hole in his ear. When he turned back to her, the English gentleman she had danced with might as well have never existed. This man was every bit a Gypsy.

As he stared at her, his cold expression was softening into a seductive smile. Though he had not been bothered by it, he must have known that she had been watching him change, and known the affect the sight of him would have on her. ‘Well? Do not sit gawking at me, woman. Do as I say. Give me your clothing.’

And for a moment, the idea beckoned to her. To be wild and carefree, and cast off her old life as easily as she had her clothes. Then the truth of the situation rushed back like cold rain, and she found her voice again. ‘Certainly not. Perhaps you have no shame and no sense. But I have no intention of removing my clothes for your entertainment.’

‘My entertainment?’ He laughed. ‘If I wished a naked woman in my vardo, I could have a new one every night, each more beautiful than the last. I do not need to take by force what will be freely given if I but ask. I have need of your clothing, and considerably less interest in the sight of your body than you had in mine.’

Not only had he known she was watching, but there was something in his smile that made her believe he had taken more time than he’d needed to change, to pique her interest. If so, then his shamelessness knew no bounds. She shuddered in disgust. ‘Your desires in the matter are of little concern to me. I am here against my will. You may think and say and do what you will, but I do not intend to cooperate in your plans for me.’

He stared at her, with the relaxed, almost lazy smile that a cat might give to a mouse. ‘Very well, then. If you will not remove your clothes, I must resort to force after all.’ He took a single step in her direction before she lost her nerve.

‘Leave me alone in the wagon, and I will do what you ask,’ she said hurriedly. ‘But if you remain …’

What would she do? She had best not offer any suggestions, or he might remain and take the clothing himself.

After what seemed like an infinity, he said, ‘I will wait outside. When you are finished, you will knock on the door and place your clothing on the step.’

She nodded, and watched as he took himself out of her presence. As the door shut, she stared at it. She was rid of the Gypsy, for now, at least. And with his absence, sanity returned, and with it, her desire to escape.

She glanced around the little room. The windows were too small for her to pass through. The only way out was through the door in front of her, and Stephano stood just on the other side. She reached for the handle and opened the door a crack.

He stood facing her, just as she had suspected, arms folded across his chest. ‘I am waiting.’

She shut the door in defeat. To disobey him might mean disaster. And he was right in one thing, at least. She was tired and dirty, and her clothing was cold and wet. The beautiful gown of white net that she had worn to the ball was little better than a rag. She was even more miserable than she might be if she removed it.

She glanced around the wagon. What was she to wear instead? Did he mean to bring her replacements? Or was it just an elaborate ruse to make her bare herself? She was shivering as she fumbled with the closures on her ball gown. She dropped it and the muddy, torn petticoats into a heap on the floor, and then bundled them up, and opened the door a crack, pushing them out toward the Gypsy.

His hand appeared in the crack in the door, and he opened it wider, but did not look in. ‘The rest, as well.’

‘Most certainly not.’

‘The stays, the shift. Stockings and shoes—’ he paused ‘—shoe, rather. You left one behind already. Remove them, or I shall.’

She slammed the door, and shouted through the wood. ‘Bastard!’ And was surprised by the sound of her own voice.

He laughed in response. ‘An accurate assessment of my parentage. But unusual to hear it from such ladylike lips. Perhaps it was the gown alone that gave you the air of gentility. Who knows what you shall be like, when you wear nothing but skin?’

‘You certainly shall not.’

He laughed again. ‘You are right in that. I must leave you alone for the day. And I will not have you thinking that, when I am gone, you can turn my people against me or make a daring escape cross country. You will find it difficult to do, if you must walk through the camp dressed as nature intended, with not even shoes for protection.’

‘You mean to leave me.’ She swallowed.

‘Better than not leaving you alone, while in that condition. Unless you prefer …’

For the second time in her life, she cursed aloud.

He laughed again. ‘I thought not. You will be perfectly safe, shut up in the wagon. No one will trouble you. No one would dare.’ There was a darkness in his tone that made her sure of the truth. And then, the smile was back in his voice. ‘And if you are good, and behave yourself in my absence? Then I shall return some of your clothing to you this evening.’

‘You will return my own things to me as a reward?’ She cursed him again.

He laughed again. ‘Not if you act in that way. Now, remove the rest. Or.’ He let the last word hang in the air, and she reached for the laces. When she had another small pile of clothes before her, she hid herself behind the door, opened it a crack and forced the things out of the wagon, then quickly slammed the door again.

There was a moment of silence, and then the Gypsy said, ‘All seems to be in order. My bed might not be to your liking, but it is the best I mean to offer. I suggest you avail yourself of it. I will return later in the day.’

And then, she heard no more.

Chapter Three

Stephano stood perfectly still in the bedroom of his London home on Bloomsbury Square, undergoing the transformation from Gypsy back to gentleman. His valet, Munch, cast aside a wrinkled strip of linen and started with a fresh cravat. ‘If you insist on starting again.’ Stephano muttered, eager to be getting on to his appointment. He had wasted hours in the night, traipsing around the countryside to befuddle the Carlow girl as to their location. And now, the delivery of the ransom demand had been complicated by Robert Veryan’s unexpected flight to London.

‘If you are going to Keddinton’s office, then the knot must be perfect.’ Munch’s flat voice came out of an equally flat face, and often left people expecting a man of limited dexterity or intelligence. But his thick fingers did not fumble as he tied the fresh knot, nor did his perception of the situation. ‘You cannot expect the man to take you seriously, if you treat him otherwise. And you cannot afford to show weakness, even something as small as a wilted cravat.’

‘True, I suppose. But damn the man for spoiling my morning. I had hoped to be done with this business before breakfast, so that I might have a decent meal and a little sleep. Now, it will take the better part of the day. It is easier to appear strong when I am rested.’

His friend and butler, Akshat, waited patiently at his right hand. ‘How are you feeling this morning, Stephen Sahib?’

In truth, he felt better than he had expected, after a sleepless night and several hours in the saddle. ‘The headache is not so bad today. After a cup of your special tea, I shall feel almost normal.’

Akshat had anticipated his request, and was stirring the special herbs that were the closest thing to a remedy for the incessant pounding in his skull. If it could keep him clear-headed for just a few more days, he had hopes that the curse would be ended, and the headache would go with it.

He drank the proffered tea, and looked at himself in the mirror. He was a new man. Or his old self, perhaps. He was no longer sure. But he knew it was Stephen Hebden the jewel merchant who was reflected in the cheval glass, as he brushed at an imaginary speck of lint on the flawless black wool. When a member of the gentry needed someone to dispose of the family diamonds, or find a jeweller to produce a paste copy of something that had been lost at hazard—or forgotten in a mistress’s bed—there was none better than Mr Hebden to handle the thing. He was discreet, scrupulously honest, and always seemed to be where he was needed, when he was needed. It said much to his knowledge of the lives of his customers.

He grinned at himself in the mirror. And if one had business of a less scrupulous nature, Mr Hebden could always count on Salterton. And then, of course, there was the Gypsy, Beshaley. Robert Veryan had dealt with all three, at one time or another. And while the servants at Bloomsbury Square were quite used to Mr Stephen’s unusual ways, Veryan found it quite upsetting to get visits from a man who could not be filed easily for future reference. Today, he would use the old man’s unease to good advantage.

Stephano glanced again at the cut of his coat. What do you think, Munch? Sombre enough to visit a viscount?’

The Indian grinned at him, and Munch said, ‘Sombre enough to attend the funeral of one.’

‘Very good. When one means to be as serious as death, one might as well dress the part.’ And the severity of the tailoring did much to clear his head of distractions for the difficult day ahead. Although he had not expected to make a trip to London for his interview with Keddinton, he would almost have deemed the kidnap a success. But he had underestimated his captive, and his reaction to her.

He resisted the urge to pull apart Munch’s carefully tied cravat while attempting to cool the heat in his blood. He had been watching the girl from a distance for weeks, convinced she was no different from a dozen other Society misses. She was lovely, of course. But a trifle less outgoing than her peers. And more malleable of opinion, if her reaction to the people around her was any indication. She seemed to follow more than she led, and she did it with so little complaint that he wondered if she was perhaps a bit slow of wit.

A deficiency of that sort would explain her tepid reaction to the gentlemen who courted her. When the men she had spurned were away from female company and felt ungentlemanly enough to comment on her, they shook their heads in disgust and announced that, although her pedigree was excellent, the girl was not quite right. Though their suits had met with approval from her father, Earl of Narborough, and her brother, Viscount Stanegate, they had been received by the lady with blank disinterest and a polite ‘No, thank you.’ It was almost as if the girl did not understand the need to marry, or the obligation to marry well.

When he had planned her abduction, Stephano had expected to have little trouble with her. Either she would go willingly into the garden because she lacked the sense not to, or she would retreat to the retiring room and he would take her in the back hall.

But he had imagined her frightened to passivity, not fighting him each step of the way. He had not expected her to work free of her bonds, nor thought her capable of tearing her virginal white ball gown to shreds in her attempt to escape.

Nor had he expected the lusciousness of the body that the dress had hidden. Or how her eyes had turned from green to golden brown as he’d held her. Or the way those changeable eyes had watched him undress. When he had planned the abduction, he had not expected to want her.

He looked again at his sober reflection in the mirror, and put aside his thoughts of sins of the flesh. While the lust that she inspired in him might have been a pleasant surprise, he did not have the time or inclination to act on it. It was an unnecessary complication if the plan was to hold her honour hostage to gain her family’s cooperation.

When he arrived at Lord Keddinton’s London home a short time later, he pushed his way past the butler, assuring the poor man that an appointment was unnecessary: Robert Veryan was always at home to him.

Keddinton sat at the desk in his office, a look of alarm on his pasty face. ‘Hebden. Is it wise to visit in daylight?’

Stephano stared down at the cowardly little man. ‘Was it wise to run back to London so soon after the disappearance of your guest? You should have taken the time to look for the girl, before declaring her irretrievable.’

‘I—I—I felt that the family must be told, in person, of what had occurred.’ The man’s eyes shifted nervously along with his story.

‘You thought to outrun me, more like. By coming here, you deviated from the instructions I set out for you. You were to await my message to you, and then you were to deliver it. It was most inconvenient for me to have to follow you here. Inconvenient, but by no means difficult.’

When Keddinton offered no further explanation, Stephano dropped the package he had brought onto the desk in front of him. ‘You will take this to Carlow.’

The man ignored his order and said, ‘The girl. Is she still safe? Because you took her from my house.’

‘Exactly as you knew I would,’ Stephano reminded him calmly. ‘We agreed on the method and location, before I took any action.’

Keddinton’s breathing was shallow, as though now that the deed was done, he was a scant inch from panic. ‘She was supposed to be in my care. And if the Carlows realize that it was I who recommended Lord Salterton to my wife …’

‘You will tell them you had no idea that the man was a problem, and that you are not even sure he was the one who took her. Her absence was not discovered until late in the evening, was it? And others had departed by that time, as well. I took care that no one saw me leaving. The corridor and the grounds were empty, as you’d promised they would be.’

‘But still …’ Keddinton seemed to be searching for a problem where none existed.

‘Thinking of your own skin, are you?’ Stephen wondered who the bigger villain might be, George Carlow, or Veryan for his easy betrayal of his old friend.

And worse, that it would happen at the expense of an innocent girl. It had been difficult for Stephano to reconcile himself to his own part in the crime. He had not stuck at kidnapping women before. But it had never ended well for him. He was almost guaranteed a headache so strong that he would be too sick to move for several days. His late mother might still want her vengeance, but it was as though she punished him for the dishonourable acts she pushed him to commit.

But though his head might feel better today, it turned his stomach at how easy it had been to persuade Verity Carlow’s godfather to help in her abduction.

Keddinton opened the package in front of him, and went even paler when he recognized the contents. It was a chemise, embroidered at the throat with the initials V C, and tied tightly about the waist with red silk rope. He looked up at Stephen with alarm. ‘My God, Hebden. You didn’t …’

‘Touch the girl?’ Stephano laughed in response. ‘Certainly not. She is worth more to me as a virgin hostage, than she is as some temporary plaything.’ But the image of the girl sprang to his mind, sprawled upon his bed with her skirts ripped near to the waist to give a tantalizing glimpse of her silk-covered legs. ‘Since you are so quick to search the package I intended for another, then you had best read the attached note.’ He quoted from memory. ‘Your daughter is safe, for now. If you wish her to return the same, then admit in public what you have done.’

‘But is this—’ he poked at the chemise and shuddered in distaste ‘—is this necessary? Surely you did not need to be quite so theatrical.’

‘Theatrical?’ He laughed again. ‘I have made both the Carlows and the Wardales shake in their beds for months, each one worrying that they would get a bit of rope in the mail. All because of a curse that would have no hold over them, if they did not secretly believe that they were deserving of punishment. And now, because I have sent you a lady’s undergarment, you think that I am developing a taste for the theatrical?’ He could still feel the softness of the garment, as he’d tied it up, and the softness of the girl that had worn it. He felt the pounding in his head begin again, as he thought of the girl, naked in the wagon, waiting for his return. If he truly wanted revenge, it would be so very easy. And so very pleasurable. He laughed louder. But the sound did nothing to stop the lurid thoughts in his head or the agony they brought with them.

Then, as if one pain would stop another, he grabbed the letter opener from Keddinton’s desk, and dragged the blade of it along his palm until a line of red appeared there. He held his hand out over the shift, watching the drops of crimson fall onto the muslin. He made a fist, and squeezed it shut, until his mind cared about nothing but its own pain and the sharp sting of the open cut.

Then he looked up at Robert Veryan, as the blood continued to drip from his hand. ‘This, you snivelling coward, is what a taste for the dramatic looks like. Tell your friend, the murderer Carlow, that for now it is my own blood that was spilled. But if he does not accede to my demands, then the next package will be soaked in his daughter’s blood. Can you manage that, without running away again?’ He leaned over the desk and watched the older man shrink away from him. It was as easy as it had ever been to intimidate him into obedience.

Keddinton gave a shaky nod. ‘If they agree to your demands, how shall I reach you?’

Stephano reached into his pocket for a handkerchief to bandage his still-bleeding hand. ‘You do not reach me, Veryan. I am unreachable. Invisible. Unfindable. As is the girl, until this is over.’

In fact, she was hidden on Veryan’s own property, less than six miles from his house. If the man had been the expert spy catcher everyone thought him, such a simple deception should have been impossible. But the profound ignorance he displayed over small things was more than a match for the intelligence he displayed in others. ‘I will return to you in a week’s time, and expect to hear George Carlow’s answer. Should you, through disobedience or incompetence, give me reason to come back here before then, it will go hard for you. Do not run, for I will have no trouble finding you, no matter where you might hide. And I will punish you. Is that understood?’

He gave Veryan a moment to remember their first meeting. He had recognized the man as a weak link in the chain that would lead him to his father’s killer. He had broken into Veryan’s private rooms, in the night. And then he had shaken the man once, as a terrier might shake a rat, and left him weeping on the floor. It had not taken a single blow to convince him to turn traitor to his friends and serve as Stephano’s right hand in vengeance.

It was just one more proof of the falseness of the honour that supposed English gentlemen held so high.

‘As long as there is nothing to lead them back to me in this,’ Veryan muttered.

‘Is that all that concerns you?’ Stephano sneered. ‘This will be over soon, Veryan, and you will be safe. Now that I have the girl, it will not take long for Carlow to reveal his part in the murder.’ Because he could not imagine the man would be so casual with the safety of his youngest daughter. ‘But it does my heart good to see your very belated care for Verity Carlow’s safety.’

‘When you asked me to help you, you promised you would not hurt her,’ Veryan said the words with a whine, as though they were a defence of his betrayal.

So Stephano leered at him and said, ‘Perhaps I regret my promise. She is a most lovely girl, and as a Gypsy, I have no honour, and am used to taking whatever I desire.’ The headache grew. And for a moment, his sight dimmed as though the pain behind his eyes was an impenetrable fog.

When his vision cleared, Veryan was gaping like a fish, eyes goggling with shock as though he were sharing an office with a fiend from hell.

Stephano sighed and took a moment to compose his features, hiding his weakness from the spymaster. Then he said, ‘If they do not tell the world of her disappearance, then no one shall know of it. Once they give me what I want, I will bring her back as quickly and secretly as I took her. She will be back in her home before anyone knows that she is missing, reputation intact and none the worse for the experience.’ And with that vaguely honourable promise, the agony diminished.

Veryan grinned at him, the sweat beading on his forehead. ‘That is good. And they will never know it was me.’

Again, back to the man’s only true fear. ‘I will certainly not tell them, Veryan. And once Carlow’s involvement in my father’s death is uncovered, no one will care how it came about.’

‘And we will be heroes,’ Keddinton said.

‘Because justice will have been done.’ Stephano repeated it as he had, several times before, to buck up the spirits of the oily little man. It was the carrot to match the stick. Keddinton had gotten it into his head that catching a traitor and murderer, after all this time, would be the thing to propel him to greater heights in government and another title. Perhaps it would. Stephano had little interest in the details. But if they helped to keep the man in line, he could think what he liked.

Now that the headache was receding, he could feel the pain in his hand again. As he flexed his fingers, he was annoyed to see blood seeping through the makeshift bandage. He glared at Keddinton. ‘Deliver the package and my message. Tell Stanegate I accosted you in the street and was gone before you could follow. He will take this to his father. I will return in a week.’ And he turned and left the proud Viscount Keddinton shaking behind his desk.

When she could no longer hear the Gypsy taunting her from outside the vardo wagon, Verity shouted a brief tirade of curses and pleas into the silence on the other side of the door. Then she fell silent herself, as she suspected that further shouting served no purpose. No one had come to help her when Stephen Hebden had brought her into the camp. If anyone wished to help her now, there could be no doubt of her location, nor the fact that she was held against her will. And since she had seen none of the other Gypsies, she did not even know if she wanted their help. Perhaps the tribe was full of men even more brutal than her captor. If that was the case, she would gain nothing by calling attention to herself. She had no proof that the person that might come to her aid was any better than the one who had taken her.

She glanced around the little room that would be her prison for the day. There was a basin with fresh water, and a small mirror on the wall. She went to it, and looked at her reflection. It was as he had said. Her face was streaked with dirt, and mud was caked under her nails. Even her feet were dirty, for the muddy water of the roadway had soaked through her stockings. Carefully, she began to wash herself. Then she took down her hair, combing the leaves out of it with her fingers, then reaching hesitantly for the set of silver brushes that sat on the small shelf below the mirror. They were beautiful things, as was the silver handle of his razor, ornamented with a pattern of leaves and vines. The metal was smooth from use, but well cared for.

And the blade of the razor was sharp. He’d left her alone with access to a weapon. What did it say about the man, that he would do such a thing? He had not seemed foolish. But if he made such a blunder, then he was underestimating her. She glanced wildly around the room, looking for a place to conceal it. If she hid the thing, it should be where she could get to it, should she need to use it. He had seen to it that there was no way for her to secrete it on her person. Her only option might be to lie in wait for him, and strike quickly when he opened the door. But for now, she returned the razor to where she’d found it.

She looked in the mirror again. At least now, she felt clean, although still just as vulnerable as she had. But it was good that she was alone, she reminded herself. The last thing she needed, in her current state, was company. She glanced around the room. In another life, she’d have found it cheerful. The wood of the bed frame and the little table and chair were carved and painted with bright designs of flowers and birds. She wondered if her captor had done the work himself, or it had been decorated by another. The chest in the corner had the name ‘Magda’ carved carefully into the top. Was the woman a wife or a lover? It was impossible to tell.

She hesitated only a moment, before opening it. It was not locked. But if he’d wanted privacy, then he’d have been better to leave her where she was, and not to lock her up here. The trunk was full of neatly folded men’s clothes, just as she had expected. Here was the suit that she had admired on him in the civilized setting of the Keddinton ballroom. Her hand was resting on the fine linen of his shirt, and she imagined slipping it over herself.

Would it be more decent or less, she wondered, for a woman to cover her nakedness with men’s clothing? To go without stays and feel the cloth of the shirt rubbing against one’s breasts, the unfamiliar sensations of trousers, covering while they revealed. And to have the whole of the ensemble bearing the faint smell of the man she had danced with. Wood smoke and brandy with an underlay of exotic spice. It would be as intimate as a touch.

The thought made her dizzy. She hoped it was the strangeness of her surroundings and her helplessness in them that was making her feel so odd. But in some part, it was because of the way she’d felt about the false Lord Salterton, right up to the moment when he had ruined it all by taking her. Although she should be terrified of him, she was more angry than frightened. For to suddenly have the fluttery feelings towards a man that she had been waiting and hoping to have, only to have them for someone so villainous, so cruel, and so clearly unworthy. She was disappointed in herself, and in him, for not being the man she wished him to be.

She pressed her hands to her temples. She must be losing her mind. She thrust the clothing back into the chest. She did not want to get any closer to her kidnapper than was necessary. There had to be a better way to solve her predicament than to put on his shirt, even if it was the most sensible course of action.

The door behind her opened.

She slammed the chest shut and jumped away from it, grabbing a blanket from the bed to hide her body and the razor from the shelf, ready to strike at the first hand that touched her.

When she turned to confront the person who had entered, she was surprised to see an old woman holding a cloth bundle in her arms. Her visitor was eyeing her with disdain, although she gave a faint nod of approval at the sight of the bare blade in her hand.

The whole tribe was as mad as Stephano, if threatening a stranger with a makeshift weapon was seen as an acceptable greeting. God only knew what he had said to the people in his camp. Despite all her screaming, Verity could guess how it must look to the old woman, if she was hiding in the man’s wagon, without a stitch on. She put on her most innocent expression, set the razor aside, and held out a hand in supplication. ‘I am held against my will,’ she whispered. ‘Can you help me?’ The blanket slipped alarmingly, and she pulled her hand back to catch it.