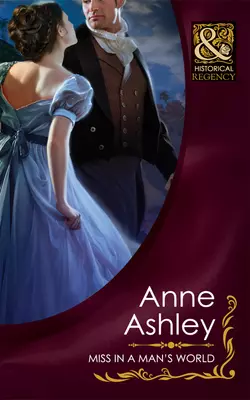

Miss In A Man′s World

ANNE ASHLEY

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: THE UNMASKING OF MISS GREY With her beloved godfather’s death shrouded in scandal, the impetuous Miss Georgiana Grey disguises herself as a boy and heads to London to discover the truth. Being hired as the notorious Viscount Fincham’s page helps Georgie’s investigations, but plays havoc with her heart…She returns home, disastrously in love with her high-handed protector, only to discover she must return to London for the Season! She comes face-to-face with Fincham at a lavish ball, and her true identity and outrageous deception are unmasked…