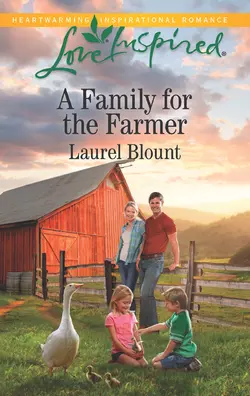

A Family For The Farmer

Laurel Blount

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 465.10 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Home to the FarmerWhen she inherits her grandmother′s farm, Emily Elliott must return to the small town she thought she′d permanently escaped. The citified single mom of twins must live on Goosefeather Farm for the summer…or lose it to neighbor and childhood friend Abel Whitlock. It′s Abel′s chance to own the land he′s always wanted, but he won′t do it at the expense of the girl he′s never forgotten—or her adorable twins. Instead, Abel will show Emily how to take care of the farm and its wayward animals. He has three months to fight for a lifetime with the family he loves.