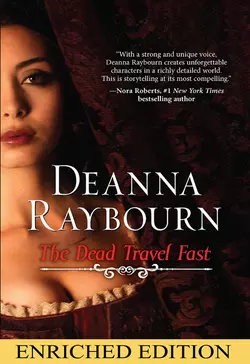

The Dead Travel Fast

Deanna Raybourn

A husband, a family, a comfortable life: Theodora Lestrange lives in terror of it all.With a modest inheritance and the three gowns that comprise her entire wardrobe, Theodora leaves Edinburgh—and a disappointed suitor—far behind. She is bound for Rumania, where tales of vampires are still whispered, to visit an old friend and write the book that will bring her true independence.She arrives at a magnificent, decaying castle in the Carpathians, replete with eccentric inhabitants: the ailing dowager; the troubled steward; her own fearful friend, Cosmina. But all are outstripped in dark glamour by the castle's master, Count Andrei Dragulescu.Bewildering and bewitching in equal measure, the brooding nobleman ignites Theodora's imagination and awakens passions in her that she can neither deny nor conceal. His allure is superlative, his dominion over the superstitious town, absolute—Theodora may simply be one more person under his sway.Before her sojourn is ended—or her novel completed—Theodora will have encountered things as strange and terrible as they are seductive. For obsession can prove fatal…and she is in danger of falling prey to more than desire.

This isn’t your average eBook…

Welcome to the Enriched Edition of The Dead Travel Fast by Deanna Raybourn! Be drawn even deeper into the mysterious, sensual world of novel with new exclusive material from the author. Bonus content includes:

Cast of Characters

A letter from Theodora Lestrange

Mmlig Recipe

Extended scene of Theodora’s journey to Transylvania

A sneak peek excerpt of Dark Road to Darjeeling, book four in Deanna Raybourn’s award-winning Lady Julia Grey series

We hope you enjoy this Enriched eBook. We’d love to hear about your experience and any suggestions for future editions. Send us an email at nbd@harlequin.ca.

And look for Enriched Editions of Deanna Raybourn’s Lady Julia Grey novels Silent in the Grave, Silent in the Sanctuary and Silent on the Moor, all three on sale now wherever eBooks are sold.

Happy reading!

The Dead Travel Fast

Deanna Raybourn

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For my husband. For everything. For always.

Contents

Cover (#u93f9b241-054c-5d5f-877d-a81f1e27c102)

Title Page (#u3be0f9e9-5125-5418-aaf6-6a6a77ce0c8d)

Dedication (#u906a6c95-fe1f-5166-bdc8-b039845ce771)

Characters

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Readers’ Guide Questions

Acknowledgments

Deleted Scene from The Dead Travel Fast

Letter from Theodora Lestrange

M

m

lig

Recipe

Excerpt from Dark Road to Darjeeling

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Characters (#u6ee76e75-1cc9-59a2-a3da-3263512699b0)

Theodora Lestrange, an aspiring novelist and seeker of adventure

Charles Beecroft, her publisher and erstwhile suitor

Anna and William, Theodora’s sister and brother-in-law

Mrs. Muldoon, Theodora’s housekeeper

Cosmina Dragulescu, Theodora’s school friend

Countess Eugenia Dragulescu, her aunt

Count Andrei Dragulescu, son to the countess and master of the Castle Dragulescu

Frau Amsel, companion to the countess

Florian, her son, the acting steward of the castle

Frau Graben, the cook

Tereza, a maid at the castle

Aurelia, her sister, also a maid

Count Bogdan, the deceased count who may not lie easily in his grave

Dr. Frankopan, doctor and friend to the countess

Madam Popa, his housekeeper and wife to a man with a terrible secret

The villagers, peasant folk who inhabit the valley below the castle and serve the Dragulescus

The pedlar, a traveller

Herr Engel, proprietor of a rest home

I

As he spoke, he smiled, and the lamplight fell on a hard-looking mouth, with very red lips and sharp-looking teeth, as white as ivory. One of my companions whispered to the other…“Denn die Todten reiten schnell.” (“For the dead travel fast.”)

—Bram Stoker, Dracula

It is with true love as it is with ghosts, which everyone talks about and few have seen.

—François de la Rochefoucauld

II

All proper stories begin with the words Once upon a time…. But this is not a proper story—it is mine. You will not believe it. You will say such things are not possible. But you believed once, long ago. You believed in witches and goblins and things that walked abroad in the dark of the night. And you believed in happily ever after and that love can mend all. For children believe in impossible things. So read my tale with a child’s eyes and believe once more in the impossible….

1 (#ulink_57c9b7ad-2aca-5de0-ae26-76ffbd7c5b01)

Edinburgh, 1858

“I am afraid we must settle the problem of what to do with Theodora,” my brother-in-law said with a weary sigh. He looked past me to where my sister sat stitching placidly on a tiny gown. It had been worn four times already and wanted a bit of freshening.

Anna glanced up from her work to give me a fond look. “I rather think Theodora ought to have a say in that, William.”

To his credit, he coloured slightly. “Of course she must.” He sketched a tiny bow in my direction. “She is a woman grown, after all. But now that Professor Lestrange has been properly laid to rest, there is no one here to care for her. Something must be decided.”

At the mention of my grandfather, I turned back to the bookshelf whose contents I had been sorting. His library had been an extensive one, and, to my anguish, his debts demanded it be sold along with anything else of value in the house. Indeed, the house itself would have to be sold, although William had hopes that the pretty little property in Picardy Place would fetch enough to settle the debts and leave me a tiny sum for my keep. I wiped the books carefully with a cloth sprinkled with neat’s-foot oil and placed them aside, bidding farewell to old friends.

Just then the housekeeper, Mrs. Muldoon, bustled in. “The post, Miss Lestrange.”

I sorted through the letters swiftly, passing the business correspondence to William. I kept only three for myself, two formal notes of condolence and the last, an odd, old-fashioned-looking letter written on thick, heavy paper and embellished with such exotic stamps and weighty wax seals that I knew at once who must have sent it. I hesitated to open it, savouring the pleasure of anticipation.

William showed no such restraint. He dashed a paper knife through the others, casting a quick eye over the contents.

“More debts,” he said with a sigh. He reached for the ledger, entering the numbers with a careful hand. It was good of him to settle my grandfather’s affairs so diligently, but at the moment I wanted nothing more than to be rid of him with his ledgers and his close questions about how best to dispose of a spinster sister-in-law of twenty-three.

Catching my mood, Anna smiled at her husband. “I find I am a little unwell. Perhaps some of Mrs. Muldoon’s excellent ginger tea might help.”

To his credit, William sprang up, all thoughts of me forgotten. “Of course.” Naturally, neither of them alluded to the happy source of her sickness, and I wondered wickedly how happy the news had been. A fifth little mouth to feed on his modest living in a small parish. Anna for her part looked tired, her mouth drawn.

“Thank you,” I told her when he had gone. I thrust my duster into my pocket and took up the paper knife. It seemed an act of sacrilege to destroy the seal, but I was wildly curious as to the contents.

Anna continued to stitch. “You must not be too impatient with William,” she advised me as I began to read. “He does care for you, and he means well. He only wants to see you properly settled.”

I mumbled a reply as I skimmed the letter, phrases catching my eye. My dearest friend, how I have missed you…at last he is coming to take up his inheritance…so much to be decided…

Anna chattered on for a few moments, trying to convince me of her husband’s better qualities, I think. I scarce listened. Instead I began to read the letter a second time, more slowly, turning each word of the hasty scrawl over in my head.

“Deliverance,” I breathed, sinking onto a hassock as my eyes lingered upon the last sentence. You must come to me.

“Theodora, what is it? Your colour has risen. Is it distressing news?”

After a moment, I found my voice. “Quite the opposite. Do you remember my school friend, Cosmina?”

Anna furrowed her brow. “Was she the girl who stayed behind during holidays with you?”

I had forgot that. After Anna had met and promptly married William at sixteen, I had been bereft. She had left us for his living in Derbyshire, and our little household never entirely recovered from the loss. She was but two years my senior, and we had been orphaned together in childhood. We had been each other’s bulwark against the loneliness of growing up in an elderly scholar’s household, and I had felt the loss of her keenly. I had pined so deeply in fact, that my grandfather had feared for my health. Thinking it a cure, he sent me to a school for young ladies in Bavaria, and there I had met Cosmina. Like me, she did not make friends easily, and so we had clung to each other, both of us strangers in that land. We were serious, or so we thought ourselves, scorning the silliness of the other girls who talked only of beaux and debut balls. We had formed a fast friendship, forged stronger by the holidays spent at school when the other pupils who had fewer miles to travel had been collected by their families. Only a few of the mistresses remained to keep charge of us and a lively atmosphere always prevailed. We were taken on picnics and permitted to sit with them in the teachers’ sitting room. We feasted on pastries and fat, crisp sausages, and were allowed to put aside our interminable needlework for once. No, we had not minded our exile, and many an evening we whiled away the hours telling tales of our homelands, for the mistresses had travelled little and were curious. They teased me fondly about hairy-kneed Highlanders and oat porridge while Cosmina made them shiver with stories of the vampires and werewolves that stalked her native Transylvania.

I collected myself from my reverie. “Yes, she was. She always spoke so bewitchingly of her home. She lives in a castle in the Carpathians, you know. She is kin to a noble family there.” I brandished the letter. “She is to be married, and she begs me to come and stay through Christmas.”

“Christmas! That is months away. What will you do with yourself for so long in…goodness, I do not even know what country it is!”

I shrugged. “It is its own country, a principality or some such. Part of the Austrian Empire, if I remember rightly.”

“But what will you do?” Anna persisted.

I folded the letter carefully and slipped it into my pocket. I could feel it through my petticoats and crinoline, a talisman against the worries that had assailed me since my grandfather had fallen ill.

“I shall write,” I said stoutly.

Anna primmed her lips and returned to her needlework.

I went and knelt before her, taking her hands in mine, heedless of the prick of the needle. “I know you do not approve, but I have had some success. It wants only a proper novel for me to be established in a career where I can make my own way. I need be dependent upon no one.”

She shook her head. “My darling girl, you must know this is not necessary. You will always have a home with us.”

I opened my mouth to retort, then bit the words off sharply. I might have wounded her with them. How could I express to her the horror such a prospect raised within me? The thought of living in her small house with four—now five!—children underfoot, too little money to speak to the expenses, and always William, kindly but disapproving. He had already made his feelings towards women writers quite clear. They were unyielding as stone; he would permit no flexibility upon the point. Writing aroused the passions and was not a suitable occupation for a lady. He would not even allow my sister to read any novel he had not vetted first, reading it carefully and marking out offending passages. The Brontës were forbidden entirely on the grounds that they were “unfettered.” Was this to be my future then? Quiet domesticity with a man who would deny me the intellectual freedoms I had nurtured for so long in favour of sewing sheets and wiping moist noses?

No, it was not to be borne. There was no possibility of earning my own keep if I lived with them, and the little money I should have from my grandfather’s estate would not sustain me long. I needed only a bit of time and some quiet place to write a full-length novel and build upon the modest success I had already enjoyed as a writer of suspenseful stories.

I drew in a calming breath. “I am grateful to you and to William for your generous offer,” I began, “but it cannot be. We are different creatures, Anna, as different as chalk and cheese, and what suits you should stifle me just as my dreams would shock and frighten you.”

To my surprise, she merely smiled. “I am not so easily shocked as all that. I know you better than you credit me. I know you long to have adventures, to explore, to meet interesting people and tell thrilling tales. You were always so, even from an infant. I remember you well, walking up to people and thrusting out your hand by way of introduction. You never knew a stranger, and you spent all your time quizzing everyone. Why did Mama give away her cherry frock after wearing it only twice? Why could we not have a monkey to call for tea?” She shook her head, her expression one of sweet indulgence. “You only stopped chattering when you were asleep. It was quite exhausting.”

“I do not remember, but I am glad you told me.” It had been a long time since Anna and I had shared sisterly confidences. I had seen her so seldom since her marriage. But sometimes, very occasionally, it felt like old times again and I could forget William and the children and the little vicarage that all had better claims upon my sister.

“You would not remember. You were very small. But then you changed after Papa died, became so quiet and close. You lost the trick of making friends. But I still recall the child you were, your clever antics. Papa used to laugh and say he ought to have called you Theodore, for you were fearless as any boy.”

“Did he? I scarce remember him anymore. Or Mama. It’s been just us for so long.”

“And Grandfather,” she said with a smile of gentle affection. “Tell me about the funeral. I was very sorry to have been left behind.”

William had not thought it fit for a lady in her interesting condition to appear at the funeral, although her stays had not even been loosened. But as ever, she was obedient to his wishes, and I had gone as the last remaining Lestrange to bid farewell to the kindly old gentleman who had taken us in, two tiny children left friendless in a cold world.

Keeping my hands entwined with hers, I told her about the funeral, recounting the eulogium and the remarks of the clergyman on Grandfather’s excellent temper, his scholarly reputation, his liberality.

Anna smothered a soft laugh. “Poor Grandfather. His liberality is why your prospects are so diminished,” she said ruefully.

I could not dispute it. Had he been a little less willing to lend money to an impecunious friend or purchase a book from a scholar fallen upon hard times, there would have been a great deal left in his own coffers. But there was not a man in Edinburgh who did not know to apply to Professor Mungo Lestrange if he was a man of both letters and privation.

“Was Mr. Beecroft there?” she asked carefully. She withdrew her hands from mine and took up her needlework again.

I looked for something to do with my own hands and found the fire wanted poking up. I busied myself with poker and shovel while I replied.

“He was.”

“It was very kind of him to come.”

“He is my publisher, and his firm published Grandfather’s work. It was a professional courtesy,” I replied coolly.

“Rather more a personal one, I should think,” she said, her voice perfectly even. But we had not been sisters so long for nothing. I detected the tiny note of hope in her tone, and I determined to squash it.

“He has asked me to marry him,” I told her. “I have refused him.”

She jumped and gave a little exclamation as she pricked herself. She thrust a finger into her mouth and sucked at it, then wrapped it in a handkerchief.

“Theodora, why? He is a kind man, an excellent match. And if any husband ought to be sympathetic to a wifely pen it is a publisher!”

I stirred up the coals slowly, watching the warm pink embers glow hotly red under my ministrations. “He is indeed a kind man, and an excellent publisher. He is prosperous and well-read, and with a liberal bent of mind that I should scarce find once in a thousand men.”

“Then why refuse him?”

I replaced the poker and turned to face her. “Because I do not love him. I like him. I am fond of him. I esteem him greatly. But I do not love him, and that is an argument you cannot rise to, for you did not marry without love and you can hardly expect it of me.”

Her expression softened. “Of course I understand. But is it not possible that with a man of such temperament, of such possibility, that love may grow? It has all it needs to flourish—soil, seed and water. It requires only time and a more intimate acquaintance.”

“And if it does not grow?” I demanded. “Would you have me hazard my future happiness on ‘might’? No, it is not sound. I admit that with time a closer attachment might form, but what if it does not? I have never craved domesticity, Anna. I have never longed for home and hearth and children of my own, and yet that must be my lot if I marry. Why then would I take up those burdens unless I had the compensation of love? Of passion?”

She raised a warning finger. “Do not collect passion into the equation. It is a dangerous foe, Theodora, like keeping a lion in the garden. It might seem safe enough, but it might well destroy you. No, do not yearn for passion. Ask instead for contentment, happiness. Those are to be wished for.”

“They are your wishes,” I reminded her. “I want very different things. And if I am to find them, I cannot tread your path.”

We exchanged glances for a long moment, both of us conscious that though we were sisters, born of the same blood and bone, it was as if we spoke different dialects of the same language, hardly able to take each other’s meaning properly. There was no perfect understanding between us, and I think it grieved her as deeply as it did me.

At length she smiled, tears blurring the edges of her lashes. She gave a sharp sniff and assumed a purposeful air. “Then I suppose you ought to tell me about Transylvania.”

The rest of that day was not a peaceful one. William was firmly opposed to the notion of my sojourn in the Carpathians and it took all of Anna’s considerable powers of persuasion even to bring the matter into the realm of possibility. I did not require William’s permission—he had no legal claim upon me—but I wanted peace between us. At length I withdrew from my labours in the library, leaving them to speak alone and therefore more freely. I had little doubt Anna could convince him of the merits of my plan. She had only to stress the cramped condition of the vicarage and the noble status of my hosts, for William had a touch of the toady about him.

But it reflected very poorly upon me as a woman of independence that I even cared for his opinion, I told myself with some annoyance. I took up my things and informed Mrs. Muldoon I meant to walk before dinner—no unusual thing, for strenuous walking had always been my preferred method for banishing either gloom or anger. I set my steps for Holyroodhouse and the looming bulk of Arthur’s Seat. A scramble to the top of the hill would banish the fractiousness that had settled on me with my grandfather’s passing. Physical exertion and a brisk wind were just the trick to freshen my perspective, and as I climbed I felt the weight of the previous dark days rolling from me. The view was spectacular, ranging from the grey fringes of the firth to the crouching mass of the castle at the end of the Royal Mile. I could see the dark buildings of the old town, huddled together in whispered conversation over the narrow, thief-riddled closes, the atmosphere thick with secrets and disease. To the west rose the elegant white squares of New Town, orderly and sedate. And I perched above it all, breathing in the fresh air that smelled of grass and sea and possibility.

“I thought I would find you here.” I turned to see Charles Beecroft just hoving into sight, breathing rather heavily, his face quite pink. “I called in at the house, and Mrs. Muldoon was kind enough to direct me here.”

He climbed the last few steps, relying upon the kind offices of his walking stick to support him. He was not elderly, although he acknowledged himself to be some fifteen years my senior. But his had been a sedentary life with little occupation outside either the opera or the offices and no country pursuits to speak of. He was a creature of the city, more accustomed to the drawing room than the meadow.

“You needn’t have come all this way, Charles,” I said, smiling a little to take the sting from my words. “I know how much you dislike fresh air.”

He laughed, knowing I meant him no insult. “But I like you, and that compels me.”

It was unlike Charles to be gallant. I steeled myself, knowing what must come next. He stood beside me, both of us intent upon the view for a long moment. He reached into his pocket and withdrew a few sweets. He offered one to me, but I refused it. Charles always carried a supply of sweets in his pockets. It was an endearing habit, for it made a boy of this serious, solid man. One would look him over carefully, from the hair so tidily combed with lime cream to the tips of his beautifully polished shoes, and one would expect him to smell of money and books. Instead he smelled of honey and barley sugar. It was one of the things I liked best about him.

“So,” he said at last, “Transylvania.” It was not a question. He has accepted it, I thought. I was conscious of a sudden unbending, a feeling of relief. I had expected Charles to be difficult, to throw obstacles in my path. But he had, very occasionally, demonstrated a rather shrewd understanding of my character. He knew I could be bridled only so tightly before I would snap the reins altogether.

“You have met my sister,” I said.

“Your brother-in-law was kind enough to introduce me. A lovely woman, your sister.”

“Yes, Anna always was the beauty.”

He sucked at the sweet. “You underestimate your charms, Theodora. Now, I know you mean to go and I have no authority to stop you. But I will ask you again to consider my proposal.”

I opened my mouth, but to my astonishment, he grasped my arms and turned me to face him. Charles had never taken such physical liberties with me, and I confess I felt rather exhilarated by the change in him. “Charles,” I murmured.

His eyes, a soft spaniel brown, were intent as I had seldom seen them, and his grip upon my arms was firm, almost painfully so. “I know you have refused me, but I do not mean to give up the idea so easily. I want you to think again, and not for a moment. I want you to think for the months you will be away. Think of me, think of the ways I could make you happy. Think of what our life together could be. And then, when you have had that time, only then will I accept your answer. Will you do that for me?”

I looked into his face, that pleasant, kindly face, and I searched for something—I did not know what, but I knew that when he grasped me in his arms, I had felt a glimmer of it, something less than civilised, something that clamoured in the blood. But it was gone, as quickly as it had come, and I wondered if I had been mad to look for real passion in him. Was he capable of such emotion?

“Kiss me, Charles,” I said suddenly.

He hesitated only a moment, then settled his lips over mine. His kiss was a polite, respectful thing. His mouth was warm and pleasant, but just when I would have put my arms about his neck in invitation, he stepped back, dropping his hands from my arms. His complexion was flushed, his gaze averted. He had tasted of honey, and I was surprised at how much I had been stirred by his kiss. Or would any man’s kiss have done?

“I am sorry,” I said, straightening my bonnet. “I ought not to have asked that of you.”

“Not at all,” he said lightly. He cleared his throat. “You give me reason to hope. You will consider my proposal?” he urged.

I nodded. I could do that much for him at least.

“Excellent. Now tell me about Transylvania. I do not like the scheme at all, you understand, but your sister tells me you mean to write a novel. I cannot dislike that.”

He offered his arm and we began to descend the hill, walking slowly as we talked. I told him about Cosmina and her wonderful tales of vampires and werewolves and how she had terrified the mistresses at school with her pretty torments.

“One would have expected them to be more sensible,” he observed.

“But that is the crux. They were sensible, very much so. German teachers have no imagination, I assure you. And yet these stories were so vivid, so full of horrific detail, they would chill the blood of the bravest man. These things exist there.”

He stopped, amusement writ in his face. “You cannot be serious.”

“Entirely. The folk in those mountains believe that vampires and werewolves walk abroad in the night. Cosmina was quite definite upon the point.”

“They must be quite mad. I begin to dislike your little scheme even more,” he said as we started downward again. He guided me around a narrow outcropping of rock as I endeavoured to explain.

“They are no different from the Highlander who leaves milk out for the faeries or plants rowan to guard against witches,” I maintained. “And can you imagine what a kindle that would be to the imagination? Knowing that such things are not only spoken of in legends but are believed to be real, even now? The novel will write itself,” I said, relishing the thought of endless happy hours spent dashing my pen across the pages, spinning out some great adventure. “It will be the making of me.”

“You mean the making of T. Lestrange,” he corrected.

As yet I had published in that name only, shielding my sex from those who would criticize the sensational fruits of my pen solely on the grounds they were a woman’s work. It had been my grandfather’s wish as well, for he had lived a retiring life and though he enjoyed a wide acquaintance, he preferred to keep abreast of his friends through correspondence. He had seldom ventured abroad, and even less frequently had he entertained his friends to our house. Mine had been a quiet life of necessity, but at Charles’s words I began to wonder. What would it be like to publish under my own name? To go to London? To be introduced to the good and great? To be a literary personage in my own right? It was a seductive notion, and one I should no doubt think on a great deal while I was in Transylvania, I reflected.

“How do you mean to travel?” Charles asked, recalling me to our conversation.

“Cosmina says the railway is complete as far as someplace called Hermannstadt. After that I must go by private carriage for some distance.”

“You do not mean to go alone?”

“I do not see an alternative,” I replied, looking to blunt his disapproval.

He said nothing, but I knew him well enough to know the furrowing of his brow meant he was knitting together a plan of some sort.

“Tell me of the family you mean to stay with,” he instructed.

“Cosmina is a poor relation of the family, a sort of niece I think, to the Countess Dragulescu. The countess paid for her education and there was an expectation that Cosmina would marry her son. He was always from home when we were in school—in Paris, I think. Now his father is dead and he is coming home. The marriage will be settled, and Cosmina wishes me to be there as I am her oldest friend.”

“Why have I never heard you speak of her?”

I shrugged. “We have not seen one another since we left school. I have had only Christmas letters from her. She was never one to correspond.”

“Why has she never come to visit you?”

I made an effort to smother my rising exasperation. Charles would have made an admirable Inquisitor.

“Because she is a poor relation,” I reminded him. “She has not had the money to travel, nor has she had the liberty. She has been caring for her aunt. The countess is something of an invalid, and they lead a very quiet existence at the castle. Cosmina has had little enough pleasure in her life. But she wants me and I mean to be there,” I finished firmly.

Charles paused again and took both of my hands in his. “I know. And I know I cannot stop you, although I would give all the world to keep you here. But you must promise me this, should you have need of me, for any reason, you have only to send for me. I will come.”

I gave his hands a friendly squeeze. “That is kind, Charles. And I promise to send word if I need you. But what could possibly happen to me in Transylvania?”

2 (#ulink_f1bde38d-9ff8-55a0-a071-686cad303e1c)

And so it was settled that I was to travel into Transylvania as soon as arrangements could be made. I wrote hastily to Cosmina to accept her invitation and acknowledge the instructions she had provided me for reaching the castle. William concluded the business of disposing of my grandfather’s estate, proudly presenting me with a slightly healthier sum than either of us had expected. It was not an independence, but it was enough to see me through my trip and for some months beyond, so long as I was frugal. Anna helped me to pack, choosing only those few garments and books which would be most suitable for my journey. It was a simple enough task, for I had no finery. My mourning must suffice, augmented with a single black evening gown and a travelling costume of serviceable tweed.

Mindful of the quiet life I must lead in Transylvania, I packed sturdy walking boots and warm tartan shawls, as well as a good supply of paper, pens and ink. Charles managed to find an excellent, if slender, guidebook to the region I must travel into and a neatly penned letter of introduction with a list of his acquaintances in Buda-Pesth and Vienna.

“It is the only service I can offer you,” he told me upon presenting it. “You will have friends, even if they are at some distance removed.”

I thanked him warmly, but in my mind I had already flown from him. For several nights before my departure, I dreamt of Transylvania, dreamt of thick birch forests and mountains echoing to the howling of wolves. It was anticipation of the most delicious sort, and when the morning of my departure came, I did not look back. The train pulled out of the Edinburgh station and I set my face to the east and all of its enchantments.

We passed first through France, and I could not but stare from the window, my book unread upon my lap, mesmerised as the French countryside gave way to the high mountains of Switzerland. We journeyed still further, into Austria, and at last I began to feel Scotland dropping right away, as distant as a memory.

At length we reached Buda-Pesth where the Danube separated the old Turkish houses of Buda from the modern and sparkling Pesth. I longed to explore, but I was awakened early to catch the first train the following morning. At Klausenberg I alighted, now properly in Transylvania, and I heard my first snatches of Roumanian, as well as various German dialects, and Hungarian. Eagerly, I turned to my guidebook.

All Transylvanians are polyglots, it instructed. Roumanians speak their own tongue—to the unfamiliar, it bears a strong resemblance to the Genoese dialect of Italian—and it is a mark of distinction to speak English, for it means one has had the advantage of an English nursemaid in childhood. Most of the natives of this region speak Hungarian and German as well, although a peculiar dialect of each not to be confused with the mother tongues. However, travellers fluent in either language will find it a simple enough matter to converse with natives and, likewise, to make themselves understood.

I leafed through the brief entry on Klausenberg to find a more unsettling passage.

Travellers are advised not to drink the water in Klausenberg as it is unwholesome. The water flows from springs through the graveyards and into the town, its purity contaminated by the dead.

I shivered and closed the book firmly and made my way to the small and serviceable hotel Cosmina had directed me to find. It was the nicest in the whole of Klausenberg, my guidebook assured, and yet it would have rated no better than passable in any great city. The linen was clean, the bed soft and the food perfectly acceptable, although I was careful to avoid the water. I slept deeply and well and was up once more at cockcrow to take my place on the train for the last stage of my journey, the short trip to Hermannstadt and thence by carriage into the Carpathians proper.

Almost as soon as we departed Klausenberg, we passed through the great chasm of Thorda Cleft, a gorge whose honeycombed caverns once sheltered brigands and thieves. But we passed without incident, and from thence the landscape was dull and unremarkable, and it was a long and rather commonplace journey of half a day until we reached Hermannstadt.

Here was a town I should have liked to have explored. The sharply pointed towers and red tiled roofs were so distinctive, so charming, so definably Eastern. Just beyond the town I could see the first soaring peaks of the Carpathians, rising in the distance. Here now was the real Transylvania, I thought, shivering in delight. I wanted to stand quietly upon that platform, but there was no opportunity for reflection. No sooner had I alighted from the train from Klausenberg than I was taken up by the hired coach I had been instructed to find. A driver and a postilion attended to the bags, and inside the conveyance I discovered a handful of other passengers who demonstrated a respectful curiosity, but initiated no conversation. The coach bore us rapidly out of the town of Hermannstadt and up into the Transylvanian Alps.

The countryside was idyllic. I was enchanted with the Roumanian hamlets for the houses were quite different than any I had seen before. There was no prim Scottish thrift to be found here. The eaves were embellished with colourful carvings, and gates were fashioned of iron wrought into fantastic shapes. Even the hay wagons were picturesque, groaning under the weight of the harvest and pulled by horses caparisoned with bell-tied ribbons. Everything seemed as if it had been lifted from a faery tale, and I tried desperately to memorise it all as the late-afternoon sun blazed its golden-red light across the profile of the mountains.

After a long while, the road swung upward into the high mountains, and we moved from the pretty foothills to the bold peaks of the Carpathians. Here the air grew suddenly sharp, and the snug villages disappeared, leaving only great swathes of green-black forests of fir and spruce, occasionally punctured by high shafts of grey stone where a ruined fortress or watchtower still reached to the darkening sky, and it was in this wilderness that we stopped once more, high upon a mountain pass at a small inn. A coach stood waiting, this one a private affair clearly belonging to some person of means, for it was a costly vehicle and emblazoned with an intricate coat of arms. The driver alighted at once and after a moment’s brisk conversation with the driver of the hired coach, took up my boxes and secured them.

He gestured towards me, managing to be both respectful and impatient. I shivered in my thin cloak and hurried after him.

I paused at the front of the equipage, startled to find that the horses, great handsome beasts and beautifully kept, were nonetheless scarred, bearing the traces of some trauma about their noses.

“Die Wölfe,” he said, and I realised in horror what he meant.

I replied in German, my schoolgirl grammar faltering only a little. “The wolves attack them?”

He shrugged. “There is not a horse in the Carpathians without scars. It is the way of it here.”

He said nothing more but opened the door to the coach and I climbed in.

Cosmina had mentioned wolves, and I knew they were a considerable danger in the mountains, but hearing such things amid the cosy comforts of a school dormitory was very different to hearing them on a windswept mountainside where they dwelt.

The coachman sprang to his seat, whipping up the horses almost before I had settled myself, so eager was he to be off. The rest of the journey was difficult, for the road we took was not the main one that continued through the pass, but a lesser, rockier track, and I realised we were approaching the headwaters of the river where it sprang from the earth before debouching into the somnolent valley far below.

The evening drew on into night, with only the coach lamps and a waning sliver of pale moon to light the way. It seemed we travelled an eternity, rocking and jolting our way ever upward until at last, hours after we left the little inn on the mountain pass, the driver pulled the horses to a sharp halt. I looked out of the window to the left and saw nothing save long shafts of starlight illuminating the great drop below us to the river. To the right was sheer rock, stretching hundreds of feet to the vertical. I staggered from the coach, my legs stiff with cold. I breathed deeply of the crisp mountain air and smelled juniper.

Just beyond lay a coach house and stables and what looked to be a little lodge, perhaps where the coachman lived. He had already dismounted and was unhitching the horses whilst he shouted directions to a group of men standing nearby. They looked to be of peasant stock and had clearly been chosen for their strength, for they were diminutive, as Roumanians so often are, but built like oxen with thick necks and muscle-corded arms. An old-fashioned sedan chair stood next to them.

Before I could ask, the driver pointed to a spot on the mountainside high overhead. Torches had been lit and I could see that a castle had been carved out of the living rock itself, perched impossibly high, like an eagle’s aerie. “That is the home of the Dragulescus,” he told me proudly.

“It is most impressive,” I said. “But I do not understand. How am I to—”

He pointed again, this time towards a staircase cut into the rock. The steps were wide and shallow, switching back and forth as they rose over the face of the mountain.

“Impossible,” I breathed. “There must be a thousand steps.”

“One thousand, four hundred,” he corrected. “The Devil’s Staircase, it is called, for it is said that the Dragulescu who built this fortress could not imagine how to reach the summit of the mountain. So he promised his firstborn to the Devil if a way could be found. In the morning, his daughter was dead, and this staircase was just as you see it now.”

I stared at him in astonishment. There seemed no possible reply to such a wretched story, and yet I felt a thrill of horror. I had done right to come. This was a land of legend, and I knew I should find inspiration for a dozen novels here if I wished it.

He gestured towards the sedan chair. “It is too steep for horses. This is why we must use the old ways.”

I baulked at first, horrified at the idea that I must be carried up the mountain like so much chattel. But I looked again at the great height and my legs shook with fatigue. I followed him to the sedan chair and stepped inside. The door was snapped shut behind me, entombing me in the stuffy darkness. A leather curtain had been hung at the window—for privacy, or perhaps to protect the passenger from the elements. I tried to move it aside, but it had grown stiff and unwieldy from disuse.

Suddenly, I heard a few words spoken in the soft lilting Roumanian tongue, and the sedan chair rocked hard, first to one side, then the other as it was lifted from the ground. I tried to make myself as small as possible before I realised the stupidity of the idea. The journey was not a comfortable one, for I soon discovered it was necessary to steel myself against the jostling at each step as we climbed slowly towards the castle.

At length I felt the chair being set down and the door was opened for me. I crept out, blinking hard in the flaring light of the torches. I could see the castle better now, and my first thought was here was some last outpost of Byzantium, for the castle was something out of myth. It was a hodgepodge of strange little towers capped by witches’ hats, thick walls laced with parapets, and high, pointed windows. It had been fashioned of river stones and courses of bricks, and the whole of it had been whitewashed save the red tiles of the roofs. Here and there the white expanses of the walls were broken with massive great timbers, and the effect of the whole was some faery-tale edifice, perched by the hand of a giant in a place no human could have conceived of it.

In the paved courtyard, all was quiet, quiet as a tomb, and I wondered madly if everyone was asleep, slumbering under a sorcerer’s spell, for the place seemed thick with enchantment. But just then the great doors swung back upon their hinges and the spell was broken. Silhouetted in the doorway was a slight figure I remembered well, and it was but a moment before she spied me and hurried forward.

“Theodora!” she cried, and her voice was high with emotion. “How good it is to see you at last.”

She embraced me, but carefully, as if I were made of spun glass.

“We are old friends,” I scolded. “And I can bear a sturdier affection than that.” I enfolded her and she seemed to rest a moment upon my shoulder.

“Dear Theodora, I am so glad you are come.” She drew back and took my hand, tucking it into her arm. The light from the torches fell upon her face then, and I saw that the pretty girl had matured into a comely woman. She had had a fondness for sweet pastries at school and had always run to plumpness, but now she was slimmer, the lost flesh revealing elegant bones that would serve her well into old age.

From the shadows behind her emerged a great dog, a wary and fearsome creature with a thick grey coat that stood nearly as tall as a calf in the field.

“Is he?” I asked, holding myself quite still as the beast sniffed at my skirts appraisingly.

“No.” She paused a moment, then continued on smoothly, “The dog is his.”

I knew at once that she referred to her betrothed, and I wondered why she had hesitated at the mention of his name. I darted a quick glance and discovered she was in the grip of some strong emotion, as if wrestling with herself.

She burst out suddenly, her voice pitched low and soft and for my ears alone. “Do not speak of the betrothal. I will explain later. Just say you are come for a visit.”

She squeezed my hand and I gave a short, sharp nod to show that I understood. It seemed to reassure her, for she fixed a gentle smile upon her lips and drew me into the great hall of the castle to make the proper introductions.

The hall itself was large, the stone walls draped with moth-eaten tapestries, the flagged floor laid here and there with faded Turkey carpets. There was little furniture, but the expanses of wall that had been spared the tapestries were bristling with weapons—swords and halberds, and some other awful things I could not identify, but which I could easily imagine dripping with gore after some fierce medieval battle.

Grouped by the immense fireplace was a selection of heavy oaken chairs, thick with examples of the carver’s art. One—a porter’s chair, I imagined, given its great wooden hood to protect the sitter from draughts—was occupied by a woman. Another woman and a young man stood next to it, and I presumed at once that this must be Cosmina’s erstwhile fiancé.

When we reached the little group, Cosmina presented me formally. “Aunt Eugenia, this is my friend, Theodora Lestrange. Theodora, my aunt, the Countess Dragulescu.”

I had no notion of how to render the proper courtesies to a countess, so I merely inclined my head, more deeply than I would have done otherwise, and hoped it would be sufficient.

To my surprise, the countess extended her hand and addressed me in lilting English. “Miss Lestrange, you are quite welcome.” Her voice was reedy and thin, and I noted she was well-wrapped against the evening chill. As I came near to take her hand, I saw the resemblance to Cosmina, for the bones of the face were very like. But whereas Cosmina was a woman whose beauty was in crescendo, the countess was fading. Her hair and skin lacked luster, and I recalled the many times Cosmina had confided her worries over her aunt’s health.

But her grey eyes were bright as she shook my hand firmly, then waved to the couple standing in attendance upon her.

“Miss Lestrange, you must meet my companion, Clara—Frau Amsel.” To my surprise, she followed this with, “And her son, Florian. He functions as steward here at the castle.” I supposed it was the countess’s delicate way of informing me that Frau Amsel and Florian were not to be mistaken for the privileged. The Amsels were obliged to earn their bread as I should have to earn mine. We ought to have been equals, but perhaps my friendship with Cosmina had elevated me above my natural place in the countess’s estimation. True, Cosmina was a poor relation, but the countess had seen to her education and encouraged Cosmina’s prospects as a future daughter-in-law to hear Cosmina tell the tale. On thinking of the betrothal, I wondered then where the new count was and if his absence was the reason for Cosmina’s distress.

Recalling myself, I turned to the Amsels. The lady was tall and upright in her posture, and wore a rather unbecoming shade of brown which gave her complexion a sallow cast. She was not precisely plump, but there was a solidity about her that put me instantly in mind of the sturdy village women who had cooked and cleaned at our school in Bavaria. Indeed, when Frau Amsel murmured some words of welcome, her English was thwarted by a thick German accent. I nodded cordially to her and she addressed her son. “Florian, Miss Lestrange is from Scotland. We must speak English to make her feel welcome. It will be good practise for you.”

He inclined his head to me. “Miss Lestrange. It is with a pleasure that we welcome you to Transylvania.”

His grammar was imperfect, and his accent nearly impenetrable, but I found him interesting. He was perhaps a year or two my elder—no more, I imagined. He had softly curling hair of middling brown and a broad, open brow. His would have been a pleasant countenance, if not for the expression of seriousness in his solemn brown eyes. I noticed his hands were beautifully shaped, with long, elegant fingers, and I wondered if he wrote tragic poetry.

“Thank you, Florian,” I returned, twisting my tongue around the syllables of his name and giving it the same inflection his mother had.

Just at that moment I became aware of a disturbance, not from the noise, for his approach had been utterly silent. But the dog pricked up his ears, swinging his head to the great archway that framed the grand staircase. A man was standing there, his face shrouded in darkness. He was of medium height, his shoulders wide and, although I could not see him clearly, they seemed to be set with the resolve that only a man past thirty can achieve.

He moved forward slowly, graceful as an athlete, and as he came near, the light of the torches and the fire played over his face, revealing and then concealing, offering him up in pieces that I could not quite resolve into a whole until he reached my side.

I was conscious that his eyes had been fixed upon me, and I realised with a flush of embarrassment that I had returned his stare, all thoughts of modesty or propriety fled.

The group had been a pleasant one, but at his appearance a crackling tension rose, passing from one to the other, until the atmosphere was thick with unspoken things.

He paused a few feet from me, his gaze still hard upon me. I could see him clearly now and almost wished I could not. He was handsome, not in the pretty way of shepherd boys in pastoral paintings, but in the way that horses or lions are handsome. His features bore traces of his mother’s ruined beauty, with a stern nose and a firmly marked brow offset by lips any satyr might have envied. They seemed fashioned for murmuring sweet seductions, but it was the eyes I found truly mesmerising. I had never seen that colour before, either in nature or in art. They were silver-grey, but darkly so, and complemented by the black hair that fell in thick locks nearly to his shoulders. He was dressed quietly, but expensively, and wore a heavy silver ring upon his forefinger, intricately worked and elegant. Yet all of these excellent attributes were nothing to the expression of interest and approbation he wore. Without that, he would have been any other personable gentleman. With it, he was incomparable. I felt as if I could stare at him for a thousand years, so long as he looked at me with those fathomless eyes, and it was not until Cosmina spoke that I recalled myself.

“Andrei, this is my friend Miss Theodora Lestrange from Edinburgh. Theodora, the Count Dragulescu.”

He did not take my hand or bow or offer me any of the courtesies I might have expected. Instead he merely held my gaze and said, “Welcome, Miss Lestrange. You must be tired from your journey. I will escort you to your room.”

If the pronouncement struck any of the assembled company as strange, they betrayed no sign of it. The countess inclined her head to me in dismissal as Frau Amsel and Florian stood quietly by. Cosmina reached a hand to squeeze mine. “Goodnight,” she murmured. “Rest well and we will speak in the morning,” she added meaningfully. She darted a glance at the count, and for the briefest of moments, I thought I saw fear in her eyes.

I nodded. “Of course. Goodnight, and thank you all for such a kind welcome.”

The count did not wait for me to conclude my farewells, forcing me to take up my skirts in my hands and hurry after him. At the foot of the stairs a maid darted forward with a pitcher of hot water and he gestured for her to follow. She said nothing, but gave me a curious glance. The count took up a lit candle from a sideboard and walked on, never looking back.

We walked for some distance, up staircases and down long corridors, until at length we came to what I surmised must have been one of the high towers of the castle. The door to the ground-floor room was shut. We passed it, mounting a narrow set of stairs that spiralled to the next floor, where we paused at a heavy oaken door. The count opened it, standing aside for me to enter. The room was dark and cold. The maid placed the pitcher next to a pretty basin upon the washstand. The count gave her a series of instructions in rapid Roumanian and she hurried to comply, building up a fire upon the hearth. It was soon burning brightly, but it did little to dispel the chill that had settled into the stone walls, and it seemed surprising to me that the room had not been better prepared as I had been expected. I began to wonder if the count had altered the arrangements, although I could not imagine why.

The room was circular and furnished in an old-fashioned style, doubtless because the furniture was old—carved wooden stuff with great clawed feet. The bed was hung with thick scarlet curtains, heavily embroidered in tarnished gold thread, and spread across it was a moulting covering of some sort of animal fur. I was afraid to ask what variety.

But even as I took inventory of my room, I was deeply conscious of him standing near the bed, observing me in perfect silence.

At length I could bear the silence no longer. “It was kind of you to show me the way.” I put out my hand for the candle but he stepped around me. He went to the washstand and fixed the candle in place on an iron prick. The little maid scurried out the door, and to my astonishment, closed it firmly behind her.

“Remove your gloves,” he instructed.

I hesitated, certain I had misheard him. But even as I told myself it could not be, he removed his coat and unpinned his cuffs, turning back his sleeves to reveal strong brown forearms, heavy with muscle. Still, I hesitated, and he reached for my hands.

He did not take his eyes from my face as he slowly withdrew my gloves, easing the thin leather from my skin. I opened my mouth to protest, but found I had no voice to do so. I was unsettled—as I had often been with Charles, but for an entirely different reason. With Charles I often played the schoolgirl. With the count, I felt a woman grown.

He paused a moment when my hands were bared, covering them with his larger ones, warming them between his wide palms. I caught my breath and I knew that he heard it, for he smiled a little, and I saw then that all he did was for a purpose.

Holding my hands firmly in one of his, he poured the water slowly over my fingers, directing the warm stream to the most sensitive parts. The water was scented with some fragrance I could not quite place, and bits of green leaves floated over the top.

“Basil,” he told me, nodding towards the leaves. “For welcome. It is the custom of our country to welcome our visitors by washing their hands. It means you are one of the household and we are bound by duty to give you our hospitality until you leave. And it means you are here under my protection, for I am the master.”

I said nothing and he took up a linen towel, cradling my hands within its softness until they were dry. He finished by stroking them gently through the cloth from wrist to fingertip and back again.

He stood half a foot from me, and my senses staggered from the nearness of him. I was aware of the scent of him, leather and male flesh commingling with something else, something that called to mind the heady, sensual odour of overripe fruit. My head was full of him and I reeled for a moment, too dizzy to keep to my feet.

His hands were firm upon my shoulders as he guided me to a chair.

“Sit by the fire,” he urged. “Tereza will return soon with something to eat. Then you must rest.”

“Yes, it is only that I am tired,” I replied, and I believed we both knew it for a lie.

He rose, his fingers lingering for a moment longer upon my shoulders, and left me then, with only a backwards glance that seemed to be comprised of puzzlement and pleasure in equal parts. I sat, sunk into misery as I had never been before. Cosmina was my friend, my very dear friend, and this man was the one she planned to marry.

It is impossible. I said the words aloud to make them true. It was impossible. Whatever attraction I felt towards him must be considered an affliction, something to rid myself of, something to master. It could not be indulged, not even be dreamt of.

And yet as I sat waiting for Tereza, I could still feel his strong fingers sliding over mine in the warm, scented water, and when I slept that night, it was to dream of his eyes watching me from the shadows of my room.

3 (#ulink_d38cbf5d-8407-587d-bf0d-f3d92e06ee80)

In the morning, I rose with vigour, determined to put my fancies of the previous evening aside. Whatever my own inclinations, the count was simply not a proper subject for any attachment. I must view him solely as my host and Cosmina’s potential husband, and perhaps, if I was quite circumspect, inspiration for a character. His demeanour, his looks, his very manner of carrying himself, would all serve well as the model for a dashing and heroic gentleman. But I would have to be guarded in my observations of him, I reminded myself sternly. I had already made myself foolish by failing to conceal my reactions to him. I could ill afford to repeat the performance. I risked making myself ridiculous, and far worse, wounding a devoted friend.

Rising, I drew back the heavy velvet draperies, surprised to see the sun shone brightly through the leaded windows of my tower room. It had seemed the sort of place the light would never touch, but the morning was glorious. I pushed open a window and gazed down at the dizzying drop to the river below. The river itself ran silver through the green shadows of the trees, and further down the valley I could see where autumn had brushed the forests with her brightly coloured skirts. The treetops, unlike the evergreens at our mountain fastness, blazed with orange and gold and every shade of flame, bursting with one last explosion of life before settling in to the quiet slumber of winter. I sniffed the air, and found it fresh and crisp, far cleaner than any I had smelled before. There was not the soot of Edinburgh here, nor the grime of the cities of the Continent. It was nothing but the purest breath of the clouds, and I drew in great lungfuls of it, letting it toss my hair in the breeze before I drew back and surveyed the room.

I found the bellpull by the fireplace and gave it a sharp tug. Perhaps a quarter of an hour later a scratch at the door heralded the arrival of a pair of maids, one bearing cans of hot water, the other a tray of food—an inefficient system, for one would surely grow cold by the time I had attended to the other—but the plump, pink-cheeked maids were friendly enough. One was the girl, Tereza, from the previous night, and the other looked to be her sister, with their glossy dark braids wound tightly about their heads and identical wide black eyes. The taller of the two was enchantingly pretty, with a ripe, Junoesque figure. Tereza was very nearly fat, but with a friendlier smile illuminating her plain face. It was she who carried the water and who attempted to make herself understood.

“Tereza,” she said, thumping her ample chest.

“Tereza,” I repeated dutifully. I smiled to show that I remembered her.

She pointed to the other girl. “Aurelia.”

I repeated the name and she smiled.

“Buña dimineaţa,” she said slowly.

I thought about the words and hazarded a guess. “Good morning?”

She turned the words over on her tongue. “Good morning. Good morning,” she said, changing the inflection. She nodded at her sister. “Good morning, Aurelia.”

Her sister would have none of it. She frowned and clucked her tongue as she removed the covers from my breakfast. She rattled off a series of words I did not understand, pointing at each dish as she did so. There was a bowl of porridge—not oat, I realised, but corn—bread rolls, new butter, a pot of thick Turkish coffee and a pot of scarlet cherry jam. Not so different from the breakfasts I had been accustomed to in Scotland, I decided, and I inclined my head in thanks to her. She sketched a bare curtsey and left. Tereza lingered a moment, clearly interested in conversation.

“Tereza,” she said again, pointing to herself.

“Miss Lestrange,” I returned.

She pondered that for a moment, then gave it a try. “Mees Lestroinge.” She garbled the pronunciation, but at least it was a beginning.

“Thank you, Tereza,” I said slowly.

She nodded and dropped a better curtsey than her sister had. As she turned to leave, she spied the open window and began to speak quickly in her native tongue, warning and scolding, if her tone was anything to judge. She hurried to the window and yanked it closed, making it fast against the beautiful morning. From her pocket she drew a small bunch of basil that had been tied neatly with a bit of ribbon. This she fixed to the handle, wagging her finger as she instructed me. I could only assume I was being told not to remove it, and once the basil was in place, she drew the draperies firmly closed, throwing the room into gloom.

I protested, but she held up a hand, muttering to herself, and I heard for the first time the word I would come to hear many times during my sojourn in Transylvania. Strigoi. She bustled about, lighting candles and building up the fire on the hearth to light the room. It was marginally more cheerful when she had done so, but I could not believe I was expected to live in this chamber with neither light nor air.

She lit the last candle and moved to me then, her tone insistent as she spoke. After a moment she raised her hand and placed it on my brow, making the swift sign of Orthodoxy, crossing from right to left. Then she kissed me briskly on both cheeks and motioned towards my breakfast, gesturing me to eat before the food grew cold.

She left me then and I sat down to my porridge and rolls, marvelling at the strangeness of the local folk.

After my tepid breakfast and even colder wash, I dressed myself carefully in a day gown of deep black and left my room to search out Cosmina. I had little idea where she might be at this time of day, but it seemed certain she would be about. I hoped to have a thorough discussion with her to settle the many little questions that had arisen since my arrival. Most importantly, I was determined to discover what mystery surrounded her betrothal.

I retraced my steps from the night before, keeping a careful eye upon the various landmarks of the castle—here a suit of armour, there a peculiar twisting stair—in order to find my way. I made but two wrong turnings before I reached the great hall, and I saw that it was quite empty, the hearth cold and black in the long gloom of the room.

And then I was not alone, for in the space of a heartbeat he appeared, the great grey dog at his heels, as suddenly as if I had conjured him myself.

“Miss Lestrange,” he greeted. He was freshly shaven and dressed impeccably in severe black clothing that was doubtless all the more costly for its simplicity. Only the whiteness of his shirt struck a jarring note in the shadowy hall.

My heart had begun to race at the sight of him, and I took a calming breath.

“Buña dimineaţa, sir.” I noticed then the cleft in his chin, and I thought of the proverb I had often heard at home: Dimple in the chin, the Devil within.

His face lit with pleasure. “Ah, you are learning the language already. I hope you have passed a pleasant night.”

“Very,” I told him truthfully. “It must be the air here. I slept quite deeply indeed.”

“And your breakfast was to your liking?” he inquired.

“Very much so, thank you.”

“And the servants, they are attentive to your desires?” It struck me then that his voice was one of the most unusual I had ever heard, not so much for the quality of the sound itself, which was low and pleasing, but for the rhythm of his speech. His accent was slight, but the liquidity of a few of his consonants, the slow pace of his words, combined to striking effect. The simplest question could sound like a philosopher’s profundity from his lips.

“Quite. Although—”

“Yes?” His eyes sharpened.

“The maid seemed a little agitated this morning when she discovered my open window.”

“Surely you did not sleep with it open,” he said quickly.

“No, it would have been too cold for that, I think. But it was such a lovely morning—”

He gave a little sigh and the tension in his shoulders seemed to ease. “Of course. The maid doubtless thought you had slept with the window open, and such is a dangerous practise here in the mountains. There are bats—vespertilio—which carry foul diseases, and other creatures which might make their way into your room at night.”

I grimaced. “I am afraid I do not much care for bats. Of course I shall keep my window firmly closed in future. But when Tereza closed it, she hung basil from the latch.”

“To sweeten the air of the room,” he said hastily. “Such is the custom here.”

The word I had heard her speak trembled on my lips, but I did not repeat it. Perhaps I was afraid to know just yet what that word strigoi meant and why it seemed to strike fear into Tereza’s heart.

“I thought to find Cosmina,” I began.

“My mother is unwell and Cosmina attends her,” the count replied. “I am afraid you must content yourself with me.”

Just then the great dog moved forward and began to nuzzle my hand, and I saw that his eyes were yellow, like those of a wolf.

“Miss Lestrange, you must not be frightened of my Tycho! How pale you look. Are you afraid of dogs?”

“Only large ones,” I admitted, trying not to pull free of the rough muzzle that tickled my palm. “I was bitten once as a child, and I do not seem to have quite got over it.”

“You will with my boy. He is gentle as a lamb, at least to those whom I like,” he promised. The count encouraged me to pet the dog, and I lifted a wary hand to his head.

“Underneath the neck, just there on the chest, between his forelegs,” he instructed. “Over the head is challenging, and he will not like it. Under the chin is friendly, only mind the throat.”

I did not dare ask what would happen if I did not mind the throat. I put my hand between the dog’s forelegs, feeling the massive heart beating under my fingers. I patted him gently, and he leaned hard with his great head against my leg, nearly pushing me over.

“Oh!” I cried.

“Do not be startled,” the count said quietly. “It is a measure of affection. Tycho has decided to like you.”

“How kind of him,” I murmured. “A curious name, Tycho.”

“After the astronomer, Tycho Brahe. It was an interest of my grandfather’s he was good enough to share with me.” Before I could remark upon this, he hurried on. “Have you any pets, Miss Lestrange?”

“No, my grandfather had the raising of me and he did not much care for animals. He thought they would spoil his books.”

The count made a noise of derision. “And are books more important than the companionship of such creatures? Were it not for my dogs and horses I should have been quite alone as a child.” It was an observation; he said the words without pity for himself.

“I too found solace. Books remain my favourite companions.”

The strongly marked brows shifted. “Then I have something to show you. Come, Miss Lestrange.”

He led the way from the great hall, through a corridor that twisted and turned, through another lesser hall, a second corridor, and through a set of imposing double doors. The room we emerged into was tremendous in size, encompassing two floors, with a wide gallery running the perimeter of the place. Bookshelves lined both floors to the ceiling, and there were several smaller, travelling bookcases scattered about the room, all stuffed with books.

Unlike the rest of the castle, this room was floored in dark, polished wood, giving it a cosier feel, if such a thing was possible in so imposing a place. The furniture was carved and heavy and upholstered in moss green, a native pattern stitched upon it in faded gold. There were a few globes, including a rather fine celestial model, and several map tables fitted with wide, low drawers for atlases. In the centre of the room a great two-sided desk stood upon lion’s paws on a vast Turkey rug. Taken as a whole, the room was vast and impressive, but upon closer inspection it was possible to see the work of insects—moth upon the furniture and rugs and bookworm in the volumes themselves. It was a room that had been beautiful once, but beyond a cursory flick of a duster, it did not seem as if anyone had cared for it for quite a long time. A fire burning on the wide hearth did something to banish the chill, and the dog settled in front of it, claiming the place.

The count stood back, awaiting my reaction.

“A very impressive room,” I told him.

He seemed pleased. “It is traditionally used by the counts to conduct their business—the collecting of rents, the meting out of justice. And it is also a place of leisure. No doubt you think it odd to find such an extensive collection in such a place, but the grip of winter holds us close upon this mountain. There is little to do but hunt, and even that is sometimes not possible. It is then that we too turn to books.”

He moved to one of the cases and drew out a few folios. I smiled as I recognised Whitethorne’s Illustrated Folklore and Legend of the Scottish Highlands as well as Sir Ruthven Campbell’s Great Walks of the British Isles.

“You see, even here we know something of your country,” the count remarked, his eyes bright.

I put out a hand to touch the enormous volumes. The colour plates of the Whitethorne folio were exquisite, each more beautiful than the last. “Breathtaking,” I murmured.

“Indeed,” he said, and I realised how close he had come. He stood right at my shoulder, his arm grazing mine as he reached out to turn another page. There was a whisper of warm breath across my neck, just where the skin was bared between the coil of my hair and the collar of my gown. “You must come and look at them whenever you like. They are too heavy to take to your room, but the library is at your disposal.”

His arm pressed mine so slightly I might have imagined the touch. I stepped back and pretended to study an ancillary sphere.

“That is very generous of you, sir.”

He closed the folio but did not move closer to me. He merely folded his arms over his chest and stood watching me, a small smile playing over his lips.

“It costs me nothing to share, therefore it is not generous,” he corrected. “When someone offers what he can ill afford to give, only then may he be judged generous.”

I looked up from my perusal of the sphere. “Then I will say instead it is kind of you.”

“You seem determined to think well of me, Miss Lestrange. But Cosmina tells me you are an authoress. What sort of host would I be if I did not provide you with a comfortable place to work should you choose?”

He smiled then, a decidedly feline smile, predatory and slow. I did not know how to reply to him. I had no experience of such people. Sophistry was not a skill I possessed. Cosmina had told me the count had lived for many years in Paris; doubtless his companions were well-versed in polished conversation, in the parry and thrust of social intercourse. I was cast of different metal. But I thought again of my book and the use I might make of him there. He was alluring and noble and decidedly mysterious, all the qualities I required for a memorable hero. I made up my mind to engage him as often as possible in conversation, to study him as a lepidopterist might study an excellent specimen of something rare and unusual.

“You surprise me,” he said suddenly.

“In what manner?”

“When Cosmina told me she was expecting her friend, the writer from Edinburgh, I imagined a quite terrifying young woman, six feet tall with red hair and rough hands and an alarming vocabulary. And instead I find you.”

He finished this remark with a look of such genuine approbation as quite stopped my breath.

“I must indeed have been a surprise,” I said, attempting a light tone. “I like to believe I am clever, but I am no bluestocking.”

“And so small as to scarcely reach my shoulder,” he said softly, leaning a bit closer. He shifted his gaze to my hair. “I had not thought Scotchwomen so dark. Your hair is almost black as mine, and your eyes,” he trailed off, pausing a moment, his lips parted as he drew a great deep breath, smelling me as an animal might.

“Rosewater,” he murmured. “Very lovely.”

I stepped backwards sharply, ashamed at my part in this latest impropriety. “I must beg your leave, sir. I ought to find Cosmina.”

Amusement twitched at the corners of his mouth. “She is with the countess. My mother has spent a restless night and it soothes her to have Cosmina read to her.”

“I am sorry to hear of the countess’s indisposition.”

“So the responsibility of entertaining you falls to me,” he added with another of his enigmatic smiles.

“I would not be a burden to you. I am sure your duties must be quite demanding. If you will excuse me,” I began as I moved to step past him.

“I cannot,” he countered smoothly. And then a curious thing occurred. He seemed to block me with his own body, and yet he did not stir. It was simply that I knew I could not move past him and so remained where I was as he continued to speak. “It is my duty and my pleasure to introduce you to my home.”

“Really, sir, that is not necessary. I might take a book to my room or write letters.” But even as I spoke, I knew it was not to be. There was a peculiar force to his personality, and I understood then that whatever resistance I presented him was no more than the slenderest twig in his path. He would take no note of it as he proceeded upon his way.

“Letters—on such a fine day, when we might walk together? Oh, no, Miss Lestrange. I will begin your education upon the subject of Transylvania, and you will find I am an excellent tutor.”

He offered me his arm then, and as I took it, I thought for some unaccountable reason of Eve and the very little persuasion it took for the serpent to prevail.

I spent the morning with him, and he proved an amiable and courteous host. He behaved with perfect propriety once we quit the library, introducing me to the castle with a connoisseur’s eye for what was best and most beautiful, for the castle was beautiful, but tragically so. Everywhere I found signs of decay and neglect, and I became exceedingly puzzled as to what had caused the castle to fall to ruin. It had obviously been loved deeply at one time, with both care and money lavished upon it in equal measure, but some calamity had caused it to lapse into decline. It was not until we had finished the tour of the castle proper—the public rooms only, for he did not take me to the family wing nor to the tower where I slept—and emerged into the garden that I began to understand.

The morning was a cool one, but I had my shawl and the garden was walled, shielded from the wind by heavy stones. The garden was surprisingly large and had been planted with an eye to both purpose and pleasure. A goodly part was used as a kitchen garden, untidy but clearly productive, with serried rows of vegetables and the odd patch of herbs bordered by weedy gravel paths. But at the end of this was a door in the wall and beyond was a forgotten place, thick with overgrown rosebushes and trees heavy with unpicked fruit. A fountain stood in the middle, the pretty statue of Bacchus furred with mold, the water black and rank and covered with a foul slime.

I turned to find the count staring at the garden, his jaw set, his lips thin and cruel.

“I apologise,” he said tightly. “I have not yet seen it. I did not realise it had fallen into disuse. It was once a beautiful place.”

I could feel anger in him, controlled though it was, and I hurried to smooth the moment. “It is not difficult to see what lies beneath. The fountain is a copy of one at Versailles, is it not? My grandfather showed me a sketch he made during his travels as a young man. I recognise the heaps of grapes.”

“Yes,” he said, almost reluctantly. “My grandfather commissioned a copy when he planted his first vineyard. He was very proud of the first bottle of wine he produced.”

“It is an accomplishment. He did well to be proud of it,” I agreed.

To my surprise, he smiled, and it was not the casual smile he had shown before but something more heartfelt and genuine. “He needn’t have been. It was truly awful. The vines were pulled out and tilled over. But he was very fond of his Bacchus,” he finished, his eyes fixed upon the ruined statue.

“And you were very fond of him,” I said boldly.

He did not alter his gaze. “I was. He had the raising of me. Dragulescu men have always had trouble with their sons,” he said with a rueful twist of the lips. “My grandfather, Count Mircea, had neither affection nor esteem for my father. When I was born, my grandfather took it upon himself to educate me, to teach me the things that mattered to him. When he died, life here became insupportable under my father. I left for Paris and I have not been here since.”

“How long have you been away?”

He shrugged. “Twelve years, perhaps a little more.”

“Twelve years! It must seem a lifetime to you.”

“I was seldom here before that. My grandfather sent me to school in Vienna when I was eight. I returned home for holidays sometimes, but only rarely. It was so far there seemed little merit in it.”

“You must have had excellent masters in Vienna,” I ventured. “You speak English as well as any native.”

He flicked me an amused glance. “I ought to. My grandfather always said any gentleman worth the title must attend university in England. I was at Cambridge. After that, my grandfather himself took me upon the Grand Tour. It was shortly after that trip that he died.”

“How lucky you have been!” I breathed. “To have learned so much, travelled so much. And with a treasured companion.”

“You did not travel with your own grandfather?”

“No. He was quite elderly when my sister and I came to him. He preferred his books and his letters. But he travelled extensively as a young man, and he spoke so beautifully about the places he had seen, I could almost imagine I had seen them too.”

“You are growing wistful now,” the count warned.

I smiled at him. “I suppose I am. The loss is still a fresh one.” I hurried on, impulsively. “And I am sorry about your father. I understand the bereavement is recent.”

He said nothing for a moment, merely drew in a deep, shuddering breath. When he turned to me, his eyes were as cold and grey and unyielding as the castle stones.

“Your sympathy is a credit to your kindness, Miss Lestrange, but it is not necessary. I have returned home for the sole purpose of making certain he was dead.”

With that extraordinary statement, he moved to the door in the garden wall. “Come, Miss Lestrange. It grows colder and I would not have you take a chill.”

4 (#ulink_bc5f7045-553f-5f45-9fbe-9480f8f743bd)