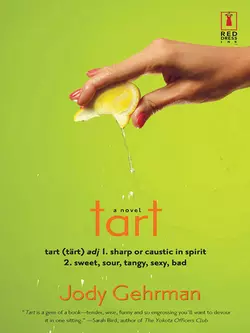

Tart

Jody Gehrman

Meet Claudia Bloom. She's having one of those years.First she steals her ex's VW bus and drives it from Austin to Santa Cruz, where it promptly explodes. Next she lets herself be rescued by Clay, a cute DJ on a motorcycle, falls hard and meets his somehow-never-mentioned estranged wife while searching frantically for her panties. She tries to forget about Clay and focus on her tenuous new career teaching theater at UC Santa Cruz, only to discover Clay's wife is her colleague and his mother is her boss. Could it get any worse? When her neo-Deadhead cousin shows up with a horse-size mutt, Rex, and the two of them take up residence on her couch, Claudia's pretty sure things have hit rock bottom.Set in the über-hip beach town of Santa Cruz, this novel explores the rocky terrain of family secrets, forbidden fruit and all things Tart.

Advance praise for Tart

“Jody Gehrman writes with a poet’s vigilance and a comic’s wit, both steeped in deep affection for her characters. In between laughing breaks, you’ll appreciate the keen eye Gehrman trains on life’s small, fine, bitter moments. Tart is aptly named.”

—Kim Green, author of Paging Aphrodite

“I loved this book. Tartis an exquisitely written and deliciously witty treat.”

—Sarah Mlynowski, author of Monkey Business

Praise for Jody Gehrman’s debut novel, Summer in the Land of Skin

“Poignant and affecting, Gehrman’s debut is brimming with vivid characters and lyrical prose. Like all good summers, you don’t want it to end.”

—Lynn Messina, author of Fashionistas

“Gehrman’s writing is crisp, her observations astute, and her story utterly absorbing and affecting.”

—Booklist

“Gehrman’s debut skillfully draws the reader in…. Her characters are confused, believable and utterly human, which is one of the main reasons the book strikes so many lonely, bewildered and true notes.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A beautifully written page-turner about love and music.”

—Lisa Tucker, author of The Song Reader

Tart

Jody Gehrman

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the professionals in my life who help keep me focused, specifically my agent, Dorian Karchmar, my editor, Margaret Marbury, and my Web designer/all-around girl genius, Rosey Larson. My continually supportive and enthusiastic colleagues at Mendocino College deserve huge kudos, especially my cohorts in the English department for their flexibility, warmth and humor, and Reid Edelman for sharing with me his favorite tales of directing disasters. Thanks to the Ukiah Writers’ Salon for helping me with my fledgling attempts at PR. An enormous thank-you to Bart Rawlinson for reading an early draft of this and for talking me down during revision-induced panic attacks. Thanks to Tommy Zurhellen, one of my most generous readers and best friends. It goes without saying that I’m completely indebted to my family for their love and inspiration, as usual. But most of all, thanks to David Wolf for helping me to believe in and laugh at myself in equal measures.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

FALL: PART 1

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

WINTER: PART 2

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

SPRING: PART 3

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 33

CHAPTER 34

CHAPTER 35

CHAPTER 36

PROLOGUE

It’s midnight in Austin, and I’m starving, but I refuse to indulge in French fries at the all-night diner; I’ve got a bus to steal.

The air is warm and rich with jasmine in an upscale, arty neighborhood near the university. It’s a Saturday night, and I can see a girl in a white halter top smoking a cigar in the kitchen across the street. I feel a pang of envy; I want to be her, a carefree chick in a skimpy ensemble, playing the tart at a party, preparing to start the school year with a hangover. I used to be her, but things have changed. Just look at me now: sweaty and furtive, crouching behind an SUV, psyching myself up for a life of crime.

The party crowd spills out onto the porch. I watch the pretty twentysomethings clutching red plastic cups and pray they’re all drunk enough to be unreliable witnesses. I inhale deeply, whisper my mantra, “He gets the jailbait, I get the wheels,” and make my move.

FALL

CHAPTER 1

I’m almost to Santa Cruz when my engine catches fire. I’ve got my entire life savings stuffed into my bra, my hair is so wind-matted I can’t even get my fingers through it, and I desperately need to change my tampon.

Things could be better.

It’s mid-September, and California’s crazy Indian summer is just getting started. The hundred-degree weather cools only slightly as I careen closer to the Pacific, where a slight tinge of fog is always hovering; it’s still plenty hot, though, and I’m sweating profusely, cursing as my temperature gauge lodges itself stubbornly in the red zone. Highway 17 is the quickest route through the Santa Cruz Mountains, but I’d forgotten just how manic it is: the crazy curves force everyone on the road into race-car-style cornering. Three pubescent surfers in a beat-up Pinto station wagon keep swerving into my lane as they pass a joint around. I honk at them instinctively; all three towheads swivel in my direction, and the car veers unsteadily toward my front fender again. I hit my steering wheel with the palm of my hand and ease onto the brakes, praying the Jaguar in my rearview mirror won’t slam me from behind. “Cunt!” one of the surfers yells. “Chill, lady,” another one adds. Did he just call me lady? Jesus, I could use a drink.

When the engine makes a sound so primal I can no longer ignore it, I pull over onto the narrow, crumbling shoulder and get out to assess the situation. The bus is producing enormous clouds of black smoke, and bright orange tongues of flame are licking at the air vents. I haven’t even bothered to check the oil since I left Austin three days ago. I knew the bus was making increasingly alarming noises, starting around El Paso, but I told myself that’s what hippie vehicles do, and turned the radio up louder. The smoke is so thick now I can barely see, and I’m afraid to open the door to the engine because I’ve got this sinking feeling it will blow my face off. Woman Found by Highway; Face Found 100 Yards Away.

Shit.

Medea, my cat, is yowling a pathetic, drugged-out plea from the back seat, so I quickly stuff her into the cardboard pet taxi and carry her out onto the shoulder with me. Then I start thinking about the cat Valium in the glove box, wondering how many of those tiny pills I’d have to take before this whole scene would take on an underwater, slow-motion sheen.

Of course, there’s something about the utter destitution of the situation that appeals to me. In theater, we’re taught that people are only as interesting as their current crisis. Jerry Manning, my favorite professor back at UT, used to scream at us, “Disaster defines you. Where’s the disaster? Come on, give me your disaster!” I feel a tiny trickle of blood as it forms a damp spot in my underwear. Medea scratches at the cardboard, her panic momentarily breaking free from the straightjacket of drugs I’ve kept her in. Her terrified mewling has gone from meek to murderous. “Here you go, Manning,” I whisper. “Here’s my disaster.”

Unfortunately, my only audience is the steady stream of traffic roaring past me at breakneck speed, making the bus shudder like a cowering animal. I stole it from my boyfriend, Jonathan, who is now officially my ex-boyfriend, but I haven’t managed to force him into the past tense just yet. If you must know, the bastard’s a Taurus and he’s got beautiful hands and he writes plays that make people swear he’s some freaky genetic hybrid: two parts Tennessee Williams, one part David Lynch. He moved to New York several months ago with Rain, this nineteen-year-old acting student with slick black hair that hangs below her ass and a five-thousand-watt smile.

The flames shooting from the engine are getting more insistent.

This is not good.

I wipe the sweat from my forehead and begin fantasizing about a very stiff, incredibly cold vodka tonic: I can see the ice, smell the carbonation, taste the green of that freshly cut lime swarming with bubbles. I think again of the cat Valium and wonder if I have enough time to secure the stash before Jonathan’s beloved VW explodes in a pyrotechnic burst of orange, like something from a Clint Eastwood flick. Woman’s Charred Remains Found Clinging to Glove Box. I squeeze my thighs together in an effort to keep the blood from running down my leg.

A guy on an old dented BMW motorcycle pulls over and takes his helmet off. He’s got a crooked smirk and a twenty-year-old body that looks oddly mismatched with the lines around his eyes. His hair is damp and stands up in hectic disarray like a child who’s just waking from a nap. The leather jacket looks ancient enough to be a hand-me-down from James Dean himself. He looks at the bus, at me, and back at the bus again.

“Need help?” he yells over the whir and wind of the passing traffic.

“Naw. Thought I’d just hang out, watch the show,” I yell back.

He shrugs and starts to swing his leg back over his bike.

“I’m kidding!” I shriek.

He turns toward me again, and a grin appears from the five o’clock shadow: white teeth, substantial lips, a nose that saves him from too pretty with a slightly swerving bridge where I’m willing to guess he broke it years ago. He’s the perfect Hamlet; he could play moody and build to insanity with enough sex appeal to keep the audience hot and bothered as Ophelia. He’s a little dirty, but in a good way. I could tell if I took a couple steps closer I’d smell the powerful perfume of leather and sweat.

Hold it together, Bloom. You’re just rebounding and road-delirious. Your cat is thrashing about in a cardboard box and you’ve stolen a vehicle that is about to go the way of Chernobyl.

He comes closer and says into my ear, “I don’t think this one’s going any farther.”

“Thanks. Excellent diagnosis.”

“What’s in the box?”

“My cat.”

He just raises his eyebrows at that. Then a huge semi comes rolling around the corner and practically knocks us over. “This isn’t a good spot,” he says.

“No kidding.” It’s a bad habit of mine: the more I need help, the more I behave like a snotty twelve-year-old. A dry, hot wind washes over us and the flames are reaching outward, like the arms of needy children. “Are we supposed to pour water on it, or something?”

“I don’t know. You got any?”

“No,” I yell, shaking my head for emphasis. Is it my imagination, or is the traffic getting louder the longer we stand here? “I’ve got a six-pack of Vanilla Coke in the back seat—will that help?”

“Not likely. What are the chances one of these assholes has a cell phone?” He watches the passing traffic with a tired, cynical expression. Jeez, strong pecs under that T-shirt. Jonathan’s chest was practically concave. With his shirt off he looked six years old. Watching this guy’s profile, with his once broken nose, his dust-smudged, stubbled chin and his blue-green eyes staring down each car as it blurs past, he looks a touch dangerous. It occurs to me that this could be a bad situation turning worse. Woman and Cat Found in Dumpster.

He starts waving his arms at the truckers and soccer moms. Medea is now yowling pathetically from the cardboard box, which I’m afraid to put down because the Valium seems to be wearing off and every five minutes she does a little body slam that nearly knocks her from my arms.

“Where’s the damn CHP when you need them?” he grumbles. At this point it occurs to me that I have every reason to avoid cops right now—or anyone who might call cops. Psycho Woman Sets Stolen Car on Fire. I squeeze Medea’s box with one hand and grab Biker Guy’s waving arm with the other. “Whoa—hold on—do you think you could just give me a lift somewhere?”

He looks at me. “Well…shouldn’t we…?” He eyes the flames. “We can’t just leave it here.”

I’ve got to think fast. I lean closer and speak into his ear, so I won’t have to yell. “Look, there’s no room here for anyone else to pull over, anyway. It’s too dangerous. Plus, what are they going to do?”

He cradles his helmet between us and studies the hillside. “Lots of dry grass around here just itching to go up in flames. It could explode,” he says.

“All the more reason to get out of here.”

“True.” I can see him assessing the situation, working the possibilities out, like someone playing chess.

“Plus, I really need a drink,” I say, feeling slightly giddy at the thought of that cool vodka tonic fizzing in my throat. “Nobody’s going to stop, anyway.”

“Pretty grim view of humanity,” he says.

“I’ll brighten up soon as you get a little vodka in me.”

We’ve just managed to bungee Medea’s box onto the back of his bike when the bus and everything I own erupts in a loud, surreal orgy of light and heat. I start to laugh. I don’t know why; it’s just the sound my body emits, without any consent. The whole thing’s an omen of some sort, but right now I’m too hot and hysterical to guess at what it all means.

“Come on,” I yell. “Let’s go!” The air is alive with the smell of gasoline, and the waves of heat are so intense it’s like swimming in an ocean just this side of scalding. He looks at me, puts his helmet on my head and says something, but I can’t hear him now because my ears are engulfed in padding. I think I can read his lips, though; I think he’s saying, “Fuck. Fuck. Fuck.”

CHAPTER 2

We should have done away with marriage long ago; by now it should be a fuzzy historical footnote, like eight-track tapes.

Unfortunately, knowing this didn’t save me from getting engaged last spring. I’d been a die-hard Amazon since my parents’ divorce, arguing with anyone who’d listen that a girl should never trade her leather bustier for a Whirlpool dishwasher, but in my late twenties, I temporarily forgot. Having sex with the same person on a regular basis can really mess with your understanding of pertinent details, like who you are, for example. I should have known things were taking a turn for the worse when Jonathan, who always prided himself in being wildly original, popped the question on one knee in a nauseatingly sunny and not at all offbeat setting. It was April and we were picnicking at a quaint park; the trees were sparkling after a light rain and toddlers were toddling across the grass and tulips were waving in the breeze, for Christ’s sake. It was mortifying, how Sound of Music it all was—especially when you consider that both Jonathan and I insist musicals are the lowest form of entertainment, right below public lynching.

Why continue submitting to a proven recipe for disaster? Take two cups pressure to conform, equal amounts fear and isolation, add a dash of childhood trauma and you’ve got marriage. Put that in the microwave with sexual urges and animal behavior, cook on high until the whole thing either caves in with apathy or explodes with infidelity. There is no such thing as a genuinely happy marriage, there are just varying degrees of skill in the performance of one.

Cynical? Maybe. I’ve earned my cynicism, though. I wear it like a Purple Heart.

My parents split up when I was eleven. My father, the shop teacher—skinny and slouching, sporting horn-rimmed glasses and pants that showed his blinding white socks—started giving it to a twenty-six-year-old dental hygienist with major cleavage. Simon does Sally. It was a mess. Calistoga (think sleepy, claustrophobic, its only claim to fame a line of mediocre beverages) had a great time laughing about it behind cupped fingers.

After the divorce, my mother moved to Marin County, studied numerology, unblocked her chakras and became an embarrassingly successful hypnotherapist. Her main clients were miserable bleach-blond divorcées driving Beemers and wearing dream catcher earrings. She started marrying with a vengeance, always with an unerring eye for the clod who would make her (and, by association, me) most miserable. I called her a serial wifer. She didn’t need them for their money; she was driven by something much deeper, more compulsive and masochistic. She once said to me, “Claudia, I don’t marry because I want to. I marry because I find it impossible not to.”

As for my father, he married the dental hygienist, who turned out to be a hypochondriac. She got out of her dental career, claiming the drills exacerbated her migraines, and sponged off my father, consuming his modest but carefully stashed savings, until a guy rolled into town who built swimming pools, and she went off with him. It was a weird time in my life, watching the drama of my parents’ love and (worse yet) sex lives unfold with the creepy predictability of a B horror flick. At first I dug my nails into my arm and tried not to scream, but by the time I was into my teens I observed it all with cool detachment, bored by the snowballing disaster of it all.

Cynical? Isn’t observant a little more accurate?

Anyway, now that my Jonathan-induced amnesia is safely behind me, I have every reason to be thrilled that he fell for a jailbait temptress and ran off with her. I should send them a dozen roses with a note: Better you than me. Let them indulge in each other’s flesh until they’re surfeit with sex and kisses and don’t-ever-leave-me-I-love-yous and the slow, torturous monotony of the future stretches out before them like the open ocean before seasick stowaways. I’m done with it all. From now on, I’ll be a warrior for non-monogamy. I’ll fight the good fight, protesting the evil of the bridal industry and romantic comedies wherever they rear their treacherous, sycophantic heads.

CHAPTER 3

Clay Parker takes me to a filthy dive on Mission Street called the Owl Club. It’s a Tuesday afternoon and there are only three customers, two old guys with faces like worn baseball gloves and a woman in tight cords playing pool by herself. She also appears to be having a solo conversation, and since no one’s bothered to feed the jukebox we can hear most of it—something about the FBI and Walter Cronkite, but it’s so complicated I tune her out after a few minutes. I’m feeling really guilty about poor Medea, who’s puffed up like one of those troll dolls after too many twirls, so I bring her in with us and hold her shaking body in my lap, trying to stroke her into submission.

“I guess we should call the cops, or something,” Clay says as he returns from the bar with our drinks.

“Cops?” My head swings toward him too quickly.

“It’s a bad time for a fire like that—could get out of hand,” he offers, but I can see by the way he’s studying me that my panic is apparent.

“I can’t.” I spent most of the ride here trying to concoct a good story, but I’m a rotten liar. I’ve been acting since I was six years old and still I can’t fib my way out of a goddamn dental appointment, let alone grand theft auto and arson, so I’ve resigned myself to telling this hapless stranger the truth. “Look, I hate to get you involved in all this,” I begin, stirring my vodka tonic quickly before downing half of it. “The thing is, I sort of—well—borrowed that bus.”

“Borrowed it?” In the dim light of the Owl Club, I can’t be sure what color his eyes are—somewhere between blue and green—but there’s something remarkably comfortable and familiar about his face. He has a stare that makes you lose your train of thought, and for a long moment I can’t remember what I’m doing here, or what I’m supposed to confess.

“If I seem incoherent, I’m sorry,” I say, looking away. “I’m a little tripped out. God, this is absolutely the most delicious and the most needed vodka tonic I’ve ever tasted.”

“You didn’t steal it, did you?”

“Well…” I try a smile, but it’s all wrong. The woman playing pool breaks and the smack of the balls makes Medea sink her claws into my thigh with alarm. “Ouch!” I cry, quite loudly, and everyone turns in my direction. I sink a little lower into the booth. Psychotic Car Thief and Mad Pussycat Apprehended at the Owl Club. “It was my boyfriend’s,” I whisper. “I just borrowed it, but he doesn’t know.”

“Aha. And where’s your boyfriend now?”

“Ex-boyfriend. Sorry. I can’t seem to get that right. He’s in New York, having sex with a teenager.”

“Charming.” He leans back, looks at the ceiling, and I can tell he’s wondering what he’s gotten himself into.

“You don’t think it’ll start a fire, do you? I mean, of course it was on fire—the explosion and all—but do you think it’ll catch?” What an idiot. Why can’t I speak?

One of the old guys at the bar laughs violently at something, and this time Medea makes a break for the door. I scramble after her, but Clay’s quicker by half; he scoops her up into his arms and has her purring in his lap before I’ve even managed to lay a hand on her. Jonathan never did get along with Medea. He claimed he was allergic, that she gave him a headache and an itchy tongue, but I always suspected it was more of a jealous grudge than a physical reaction.

Now that I’m standing, I feel a warmth spreading into my underwear again, and I realize that in my haste to get a little vodka down my throat I completely forgot about changing my tampon. I excuse myself to the ladies’ room, which turns out to be a disgustingly neglected converted broom closet. There’s a sink stained brown with rust, the floor is covered with miscellaneous paper products, and the single-stall door has been delightfully decorated with a vast array of rants, insults and warnings, the most prominent of which reads, Die Puta Bitches.

I study myself for a moment in the small, cracked mirror. My hair, even on a good day, is immune to threats with a comb. Each curl finds its way into its own contorted expression of chaos; trying to interfere leads only to excessive frizz. Today the curls have twisted to ambitious dimensions, resulting in a Medusa-on-crack look. I’m wearing this little orange sundress—the most comfortable thing I own for long drives (now, I remind myself, the only thing I own). It’s not exactly the height of chic, especially since it’s all wrinkled, the armpits are wet and the bodice is smeared here and there with the sooty remains of Jonathan’s bus. I think of Mr. Indecently Attractive out there, nursing his beer and petting my cat; perhaps it’s just as well that I’m so horrifically unpresentable today—there’s less chance of me wandering into something I really shouldn’t.

Tampon, Claudia. Focus. Oh, but goddammit, my stash of OB is now being cremated on the shoulder of Highway 17. There is a machine, thank God, but I haven’t got any change. I could go back out there and get the bartender to give me quarters. But then Clay will see me and it’ll be obvious or at the very least odd (think about it, Claudia—wouldn’t incinerating a stolen vehicle qualify as plenty odd already?). I know the chances that I’ll create a favorable impression at this point are slim (not to mention unnecessary. Remember? On the rebound, delirious with heat, on the rag, homeless, with all possessions currently blowing amid Tuesday traffic in form of ash. Do not, I repeat, do not indulge in a messy entanglement with Gorgeous Motorcycle Boy). But still, I don’t want to make things worse with one more faux pas.

There’s a gentle sniffling coming from inside the bathroom stall. I freeze. It never occurred to me that I wasn’t alone in here. A quick check under the door reveals a pair of pink flip-flops. A couple seconds pass, and then the toilet flushes and out comes Beach Barbie.

She’s wearing a tiny tank over a bikini top and miniature turquoise shorts, cut high enough to reveal her mile-long legs. Her eyes are bloodshot and her nose is pink from too much blowing, but neither this nor the seedy setting is enough to detract from her overwhelming California glow.

I try not to gawk as she squeezes past me to the sink, washes her hands and then her face, pats both dry with a paper towel.

“Hi,” I say.

She looks at me in the mirror and smiles, revealing the expected set of gleaming white teeth, then she bursts into sobs.

“Oh, no,” I say. “What is it?”

“I—” She can barely get the words out. “I hate—”

“Yes? You hate…?”

“Guys,” she finally spits out.

By now, there’s snot dripping from one of her pretty little nostrils, so I duck into the stall she just left and get her a wad of toilet paper. “There you go,” I say, patting her shoulder gently. “It’s all going to be okay.”

She blows her nose loudly several times, then composes herself quite rapidly, considering the extremity of the breakdown. “Oh, my God,” she says, checking her reflection for mascara damage. “I’m so embarrassed.”

“Don’t be. If you have a quarter or a tampon, I’m never telling anyone. Deal?”

She’s got a pink beach bag slung over her shoulder, and now she paws through it, pulling out a half-eaten Snickers bar, a bottle of aspirin, three lipsticks and a cell phone before finally producing the coveted Tampax. She hands it to me. Its paper wrapper is smooth and delicate from so much toting around.

“Oh, God, thank you,” I sigh. “You’re an angel of mercy.”

She hiccups daintily and smoothes her already perfect hair with one hand. “Our little secret, right?”

“Lips are sealed,” I say, disappearing into the stall.

When I emerge, my tragic little Beach Barbie is gone. As is usually the case, the blood damage was much less extensive than I’d feared—hardly more than a spot—so I’m feeling refreshed and eager to return to my drink. Clay is still stroking Medea. He appears to be engrossed in a conversation with her, as well. Her puffiness has completely disappeared and she is stretched out happily in his lap, soaking up the affection. She’s always had excellent taste.

“…terrible motorcycle ride,” he’s telling her, as I sit down. “But you’re okay. Bet you always land on your feet.”

“Thanks,” I say.

He looks up. “For what?”

“Oh, I don’t know…calming her down. Bringing us here. Saving us from a fiery death.”

“I hardly saved you.” He wraps a hand around his beer and rotates it slowly before taking a swig. “You two don’t look like the kind of girls who need saving.”

“Anyway,” I say, eager to change the subject, “what’s your story? What do you do?”

“For a living?”

“Okay, sure. What do you do for a living?”

He shrugs. “I’ve got a record store.”

“Here in town?” I ask.

He nods.

“That’s cool. So you’re into music. You play anything?”

“Not really. I DJ on the side, but it’s slow going. The gigs I make money at are mostly weddings, which generally suck.”

“Oh, man,” I say. “I hate weddings.”

“Jesus, if I have to play ‘You Are So Beautiful’ one more time I’m going postal.”

“I think our generation’s way too jaded for marriage. It should seriously be outlawed. Forget the whole same-sex marriage debate.” I lean into the table. “Let’s do away with the whole institution.”

He looks amused. “Now, that’s something I can drink to,” he says, raising his beer bottle. We toast, and a vision of his mouth on the nape of my neck makes me feel suddenly much drunker than half a vodka tonic can account for, even on an empty stomach.

“So what are you doing in Santa Cruz, anyway?” he asks.

He keeps turning the conversation back to me. He’s probably a serial killer. People who murder for a living tend to be rather private. One more reason not to go home with him.

“How do you know I’m not from here?” I ask, twirling my straw in my drink and looking coy in spite of myself. Stop. Flirting. Stop. Flirting.

“I had the dubious pleasure of growing up in this vortex. I can spot an outsider by now. Besides, your license plate said Texas.”

He’s an undercover cop. Oh, God. I can already feel the cold steel of the cuffs against my wrist bones.

“You okay?” He reaches across the table and gently touches the very hand I’m busy morbidly encasing in restraints. Please, Jesus, don’t let him be a serial killer undercover cop.

“Sure. Why?”

“Every once in a while you get this wild gleam in your eye—”

“Wild gleam?”

“The same look Medea shot me when I unstrapped her from my bike.”

I laugh, though even to me it sounds strangled. “Yeah, well, I’m a little off today. I don’t routinely rise at four in the morning, drive six hundred miles, then blow up my stolen vehicle to unwind in the afternoon.” Listing the events of the day makes me feel the wild gleam coming back, so I try to steer us toward safer topics. “Um, let’s see, what was your question?”

“Santa Cruz—what brings you here?”

“Right. I’ve got this university gig teaching theater.”

“Wow.” He looks impressed, and maybe a little bit skeptical, which only confirms my suspicion that I am not professor material.

“Yeah, well, they were hard up,” I explain. “Some guy faked his credentials so they had to fire him. I’m the only person they could drag here at the last minute. They made it clear that I’m just a stand-in—you know, one year and then, unless I turn out to be the next Stanislavski, I’m on the street.” The combination of my nerves, three days on the road alone and this dreamy vodka tonic are making me babble, but I hardly care. It feels good to talk to somebody other than a pissed-off, stoned cat. “I’m a total perennial student— I fell in love with the endless adolescence of college—so I figured a university’s the only place I stand a chance. Except I’m not so sure about the professor thing. I suspect I haven’t got the wardrobe for it.”

He waves a hand at me dismissively. “At UC Santa Cruz? You could walk on campus in a garbage bag and by the end of the day you’d have a following. Lack of fashion is a fashion here.”

“Yeah. Well, good.” There’s an awkward pause; we end up looking at each other for too long, and this makes me so edgy I blurt out, “Christ. I can’t believe I actually stole my ex’s bus.” He looks a little unsure about how to respond, and I realize I’m starting to monologue in a dangerously unchecked fashion. “Sorry. Very long day, as I mentioned.”

“Sounds like you could use another drink,” he says, rising. Very carefully, like one parent transferring a sleeping child into the lap of the other, he hands me Medea. “More of the same?”

I suddenly realize I’ve been gnawing nervously at the wedge of lime from my drink; even the peel is now littered with teeth marks. I toss it back into the glass, which I hand to him sheepishly. “Yes, please. Oh, but here—let me get this round.” I reach for my money, still tucked inside my bra, but he shakes his head.

“Don’t worry about it. Consider me the welcoming committee.” He turns and walks toward the bar. Watching him makes me bite the inside of my cheek. Has there ever been an icon steamier than that subtle sag of a man’s barely there butt in faded Levi’s?

I lean back against the vinyl of the booth and close my eyes, running one hand absently over Medea’s soft fur again and again. The tart taste of lime still lingers on my tongue. Claudia. Please. For once in your life, resist. Resist. Resist.

CHAPTER 4

Tart is my favorite word. I love how it tastes in your mouth—sour, tangy, just sweet enough to keep your lips from puckering around it in distaste. I love what it stirs in the mind—the synesthesia of flavor mixing with colors: buxom women in reds, oranges and apple-greens, gleaming with cheap temptation, like Jolly Ranchers. It’s been a central goal of my twenties to live a tart life; I want everything I do to have that sharpness, that edge of almost-too-out-there to be tasty, but not quite.

Until I met Jonathan, living tartly meant, for starters, never saying I love you. Which was easy, since apart from my cat, my gay roommate and my vibrator, I didn’t really love much of anything or anyone. I’m not even sure I loved Jonathan. I think our relationship was rooted in blind panic, and that, combined with great affection for him, was exactly the brand of love I’d heard about in pop songs since puberty. Being with Jonathan was terrifying, sometimes tender and studded with misery. These are the central ingredients of love, according to Top Forty tunes throughout the ages, so I figured I must be on the right track.

Before Jonathan and the Great Blind Panic, I used to think monogamy was every woman’s enemy, and that promiscuity (a central element of every tart’s lifestyle) was synonymous with freedom. It’s probably generational—lots of girls I went to college with admired strippers and porn stars the way our mothers admired starlets. It’s that fuck-you to middle-class values that inspires awe in us. We find the sex industry and all of its incumbent seediness sort of glamorous. And tart.

But being a tart can be exhausting, and after a while its rewards start to seem a little tawdry. Now that I’m rounding the corner toward my thirties, the fervor of my tart philosophy has faded some with wear. Frankly, my right to be wild, cheap and promiscuous has started to bore me.

I guess that’s part of why Jonathan and I got so serious so quickly. We met when I was twenty-eight. I could see right into my thirties from there, and beyond. I knew a change was in order. I started cringing every time I spotted some woman in her late thirties haunting the junior racks at Ross Dress for Less, sporting deeply ingrained crow’s feet and hair that’s been dyed so many times it looks like cheap faux fur. I’m not sure why self-respecting tartery requires a wrinkle-free face and body, but it does. That’s no doubt really messed up, but it feels like a force of nature too momentous to challenge.

It was in this twenty-eight-year-old climate of anxiety and pending doom that I met Jonathan. He was creative, suitably unconventional and so crazy about me that I could feel a palpable confusion coming off him anytime we were in the same room. I was directing his play, Molotov Cocktail, a farce about morticians in training, and whenever we discussed his rewrites over coffee he took every opportunity to touch me in ways that could be construed as friendly or accidental: his elbow nestled fleetingly against mine, his knee bumped against my thigh under the table. I was flattered but not overcome. I told myself he wasn’t my type—too skinny, his hands too pale, his eyes too furtive and searching, so unlike the muscular, vaguely bovine types I was used to going home with.

But Jonathan was nothing if not persistent; he rooted himself beside me and sent exploratory tendrils into my psyche with the strength and tenacity of kudzu. I started to crave the way his black hair looked in the morning light as he rolled himself a cigarette with agile fingers. I became addicted to his smell: Irish soap, cigarette smoke, Tide. He was so solicitous, as only someone with a heart that deflates between relationships can be. Jonathan loved being in love. He was lost without someone to brew coffee for, or share his favorite scripts with, or sing to sleep with funny, black-humored lullabies he made up as he went along.

He convinced me to move in with him three weeks after we first slept together. It did make some sense, since my roommate, Ziv, was involved at the time with this German guy, Gunter, who had three habits Ziv found adorable and I found repulsive: he covered the entire bathroom with a thick dusting of tiny black hairs each time he shaved; his favorite time to practice his cello was postcoital, which usually meant 2:00 or 3:00 a.m.; and he continually, despite my protests, consumed any chocolate products we smuggled into the house, including the special Belgian hazelnut bar I hid in my underwear drawer. So Gunter was driving me away, and Jonathan had this beautiful place—the upstairs of a lovely old-fashioned Texas-style minimansion with French doors, hardwood floors and a claw-foot tub I spent most of that year floating in. A warm, stable relationship and a cool new apartment to boot made cohabitation seem catalog-perfect—a Pottery Barn fairytale.

But old habits die hard. Monogamy was quite a shock to my system, both physically and philosophically. Toward the end of that summer, when we’d been living together a little over five months, I became overwhelmingly itchy for Something Else. When you’re addicted to the pursuit of all things tart, Friday night with a video and Chinese takeout is a little foreign. I’d pace the living room and blurt out nasty jabs, like a junky trying to kick.

I had lived for twenty-eight years just fine, following my sexually nomadic heart, stretching out my elastic adolescence for as long as it would last, and now suddenly half my instincts were urging me to make a nest, while the other half screamed “Flee!” Just because I’d decided to try the nesting thing didn’t mean I had the slightest idea how to pull it off.

And so I did what most people do in lieu of a solution; I denied there was a problem until I could arrange for a full-on disaster. In the fall of my last year in grad school, seven months into my experiment in cozy living with Jonathan, I had a flash-in-the-pan affair with my Set Design professor. He was in his forties, with distinguished graying temples and a gruff, Tom Waits-style lecturing voice. He was nothing to me; I had no illusions that we were doing anything except blowing off steam. The guy wasn’t even very good in bed; he was married, and felt terrible about me, so his rushed, guilt-driven exertions were never very satisfying. After two seedy sessions in a dank hotel, I called it off. He sighed with relief and gave me an A in the class, even though my final project looked like a kindergartener’s shoe-box diorama.

Of course, I had to tell Jonathan. I may not be your classic stickler for integrity, but I do have my own idiosyncratic moral code, and honesty is a central tenet, right behind tartery. Besides, half the reason I had the affair was to loosen the stranglehold my life with Jonathan exerted; telling him was key to this loosening. I’d needed a little tart back, and I’d taken it by force, but now it was necessary to fess up.

I sat him down on a cold Saturday in December. Christmas was just a week away. I summarized with my eyes averted, peeling the label from a bottle of Corona. His reaction fell short of violence, but he did dash into the john to throw up, and afterward he stared at me with the sort of expression a baby might use on his mother as she shoves his finger in an electrical outlet. At that point I felt more than a little sick, myself.

I might be saying this just to soften the sting of him leaving me months later for Rain, but in retrospect I see our relationship from that cold Saturday on as filled with him calculating his revenge. Even proposing was just one more form of payback; he knew my promise to marry him meant I’d publicly renounced all tartness, and so when he left, he took with him not only my future, but my past.

CHAPTER 5

It’s six o’clock, I’ve got three vodka tonics in my bloodstream, and I’m in love.

Okay, that’s probably not it. It’s probably just culture shock. I haven’t been home to California in three years. Obviously, the ocean air is salt-rotting my brain. That’s why I feel so reckless and giddy, like a thirteen-year-old at a slumber party.

“Where are we going?” I ask as Clay leads me out of the Owl Club and into the startling sunlight.

“We’ve got to get Medea someplace cat-friendly,” he says.

“You’re right,” I say. “Let’s strap her back onto your bike.” I giggle at my stupid joke.

Clay steers me gently east and picks up the pace. “My friend Nick lives right around the corner,” he says. “She’ll like him. He’s a spaz around people, but he’s a genius with cats.”

“What sort of spaz?”

“He’s got a mild case of Tourette’s.”

“No,” I say. “Seriously?”

“Mostly around customers. Unfortunately, he works for me at the record store. One time he called this sweet little old lady a ‘rug-eater cunt.’ You should have seen her face.”

“Oh, my God,” I say, laughing. “Isn’t that a little hard on sales?”

“Yeah, well, she wasn’t a return customer.”

As we walk the two blocks to Nick’s, my eyes keep straying to the half-moon scar near Clay’s ear. I can’t stop thinking about kissing it.

“Everything okay?” he asks, shooting me a sideways glance.

“Mmm-hmm. Why do you ask?”

“I think you might be getting that gleam in your eye again.”

I laugh. “Different gleam. You’ll have to learn the difference.”

“Right. Well, here we are,” he says, striding through a little wire gate and up the steps of a run-down house. The tilting porch is covered in thick strands of ivy and nasturtiums. “Chez Nick.” He pushes open the front door and hollers, “Nick! I brought you some kitten for dinner.”

A short guy with a receding hairline and a too-tight Ramones T-shirt appears in the living room doorway. “No need to yell.” He’s eating a doughnut, and when he sees me a big blob of jelly slips out of it and lands on the R.

“Fucking-shit-whore,” he blurts out.

Clay looks from him to me and back again. “What? She makes you nervous?”

“Sorry,” Nick says, swallowing the doughnut without chewing. He starts to choke, and Clay whacks him on the back a couple of times.

“Maybe you should wait outside.” Clay nods toward the door I’ve barely stepped through. “I’ll be there in a second.”

“Um. Okay.” I shuffle back out to the sidewalk. “Nice to meet you.”

In a couple of minutes, Clay reappears, sans Medea. He’s shaking his head.

“All righty,” he says, slapping his palms together happily. “Now we’ve officially begun the tour.”

“The tour?”

“Yes.”

“What tour, exactly?”

“The Santa Cruz Freaks and Tasty Treats Tour.”

I look over his shoulder at Nick’s dubious house. The windows are draped with purple, rust-streaked sheets, and there’s a strange sculpture made of Pabst Blue Ribbon cans dangling from a tree. “Are you sure she’ll be okay in there?”

“Positive. Like I said, he’s a disaster with women, but with cats, he really shines.”

He starts to guide me away, but still I hesitate. “I may not be a model pet owner,” I say, digging in my heels, “but I do worry. She’s sort of all I have at this point.”

With both hands on my shoulders, he looks into my eyes. “Claudia. I swear, she’ll be happy as a clam. Trust me.”

I bite my lip, studying his face. I’ve known him all of four hours and am shocked to realize I do trust him. “If you say so.”

“I promise. Now, right this way, madam, and I’ll introduce you to what Santa Cruz excels at.”

“Freaks and Treats?” I ask.

“Precisely.”

Clay Parker’s Freaks and Treats Tour:

1) Nick and his jelly doughnut. Freak with treat. I’m skeptical, but willing to proceed.

2) Fancy place downtown with white linen tablecloths and waitress with sparkly red thong peeking out of black slacks: wolf down a dozen oysters on the half shell and beer in frosty cold mugs. Clay confesses he’s having the best day he’s had all summer. I blush. I hardly ever blush.

3) En route to destination, we spy our second freak: long-hair on unicycle playing a plastic recorder. Due to high speed of vehicle, can’t be sure, but suspect he’s playing “Little Red Corvette.”

4) Gold mine. Downtown farmer’s market. Peaches, fried samosas, free samples of calamari. Too many freaks to name: mullet guys, drag queens, belly dancers, skate punks, goth girls, rasta drummers. Clay points out Dad in a Sierra Club baseball cap scolding toddler for not recycling apple juice bottle. At first we laugh, but when kid cries, start to feel depressed.

5) Manage to discreetly disappear into Rite Aid for tampons. Inside, more freaks: three betties in 80’s neon and teased bangs, filling cart with jumbo Junior Mints and Pall Malls.

6) Dessert at the Saturn Café. Sullen waitress with pink Afro. Clay orders us Chocolate Madness and a side of chocolate chip cookie dough. We feed each other the mess until we’re groaning in pain.

7) Insist on the Boardwalk. Remember visiting a hundred years ago, am seized with uncharacteristic nostalgia. Clay grudgingly admits Boardwalk is chock-full of freaks and therefore justifiable addition to itinerary. Ancient roller coaster nearly forces oysters, calamari, peaches, samosas, cookie dough and Chocolate Madness back up. Discover Clay has adorable, girlish scream when terrified.

8) Nightcap at Blue Lagoon. Lots of beefy guys in leather. Want to kiss Clay so desperately can taste it.

CHAPTER 6

Clay Parker lives in a yurt. Before tonight, I’ve never heard of such a thing. It’s round and wooden and is shaped like a circus tent. It’s more homey than I’d imagined. In fact, it has solid wooden floors, glass windows, running water and electricity. It’s the sort of place a hobbit might live in, if he was born and raised in Northern California.

You’re wondering what I’m doing here. So am I. But things are much more innocent than they sound—really—in fact, Clay’s insisted he’s going to lend me his bed while he spends the night at the smallish cottage down the road, where Friend lives. So far, the gender of Friend is a mystery my gentle probing has failed to pierce. Here’s the paltry sum of clues I’ve managed to procure:

1) Cottage has a couch, which he’s indicated he occasionally sleeps on.

2) Friend is “an old friend.” Assuming this refers to years of acquaintance, rather than somewhat comforting possibility that Friend, regardless of gender, is ninety and incontinent.

3) Friend will not mind the late hour (is now 1:00 a.m.), lack of prior notice or burden of making extra coffee come morning.

4) Friend makes great coffee.

Nancy Drew I am not. Even after nine hours of drinking, gorging and drinking again with this man, I am steadfastly incapable of asking about his romantic or (God forbid) marital status. It’s one of those sick dances we do: tell ourselves if we don’t ask, magically no obstacles will interfere. Equally sick is the assumption that, because sleeping-with candidate has not asked our status, said candidate wants what we want.

Ugh. Cannot believe I’m embroiling myself in this brand of mess yet again. But Clay Parker is absolutely bristling with sex appeal. His eyes are wise and knowing, his face all the more appealing for its minor irregularities. He’s got that endearing tiny half-moon scar near his left ear and a bicuspid with a minuscule chip missing. His left eye squints just a little more than the right, especially when he’s smiling. And then there’s the nose: that swerve toward the top, so subtle it makes you think you’ve imagined it, until you see it from a new angle and notice it again. Somewhere between the oysters and the peaches, I asked him about it. He blushed crimson.

“Whoa,” I said. “Don’t tell me—does it involve bondage and thigh-high boots?” He chuckled, but there was something wrong, and I instantly regretted asking. “You know what? It’s none of my business.”

“No, it’s fine. You can ask me anything.” Except, I thought, are you currently doing anyone? “It’s just—my dad. He was a little rough on me when I was a kid.”

“Oh. I see.” There was an awkward silence, followed by me blurting out, “He hit you?”

“A couple times.” We watched a tiny slip of a woman struggling to control her Great Dane as they crossed the street. He shrugged. “I guess nobody’s perfect.”

“Where is he now?”

“Dead.” He swallowed and held my gaze. I felt that weird surge of maternal warmth that always freaks me out—the impulse to stroke the stray wisp of hair back from a man’s forehead.

“What about your mother?”

He laughed, and though I was relieved to see him smiling again, there was something a touch hardened in the sound he made. “Oh, she’s still kicking. That old girl will outlive me, no doubt.”

“Do you like her?” Pop psychy as it is, I cling to my theory that boys who like their mothers are more satisfying in every way.

He thought about it a couple of seconds, which seemed like a bad sign, but when he answered I could tell it was just because he took the question seriously. “I do like her. I mean, we’d never hang out if she wasn’t my mother, but she’s feisty and she loves me more than anyone. That’s always irresistible.”

I just smiled, wondering if there’s anyone who loves me more than anyone.

Now that we’re here in his yurt, I’m a little daunted by the intimacy of it. I find myself standing in one big round room, lit by several candles and a brass lamp. I look around at the kitchen sink and the rustic, homemade-looking armoire and the (oh, God) king-size, quilt-covered bed all right there in plain view. We’ve been wandering for hours from one indulgence to the next, the ocean breeze messing with our hair, and now suddenly we’re encased by his bookshelves and his record player and his barbells on a thick wool rug. His dog, an old mutt the color of caramel that answers to Sandy, pants and wags her tail in a frenzy of joy as her master runs his hands all over her paunchy body.

“You surf?” I ask, noticing a large surfboard, yellowed like a smoker’s teeth, propped up next to the armoire and another, bright turquoise, near the door.

“Yeah.”

I nod. Usually, I find surfers to be a bit of a turn-off; California clichés generally make me want to heave. In this case, I can’t even work up to a sarcastic remark. Even surfing seems cool on him. “It’s a sweet place,” I say, stuffing my hands into my pockets.

“Oh, yeah? You sound surprised.”

“Well…” I shrug. “I’d never heard of a yurt. The way you described it—I mean, its Mongolian origins and all—I was picturing some yak skins stretched across a driftwood frame.”

He laughs. I like his laugh very much. It’s throaty and resonant, sexy as hell. Is it my imagination, or is it tinged now with just a shade of nerves?

“Here.” He hands me Medea, who is back in her box, probably puffed up again and pissed off. At least we did her the favor of leaving the motorcycle at Nick’s and getting him to drive us out here. She couldn’t reasonably be asked to put up with another death-defying ride, especially after all the drinks we’ve had. It was ten miles, easily, and though they were spouting off names at me—“Empire Grade” and “Bonny Doon”—I’ve no idea where we are. You’d think I might be wary, given my habitual fixation on mass murderers, but nine hours of continual conversation have allayed those fears. If Clay Parker is in any way homicidal or rape-inclined, then my instincts are so terrible I deserve to be strangled and cannibalized.

“I’ll put Sandy out so we can let Medea get her bearings.”

“Are you sure? It’s her—” I struggle to remember its name “—yurt, after all.”

“Oh, she’s dying to get out. It’s no problem.” He slips out the door with her. The yurt walls are canvas-thin, so I can hear him saying soft, reassuring doggy things to her as they crunch around in the grass.

I coax Medea out of her big-haired, frantic state again, though she can’t stop smashing her nose against all the canine-scented furniture with a mad, panicked expression. “Yes,” I murmur, trying to make my voice as warm and reassuring as Clay’s. “We’re in dog territory, babe. Don’t worry—they don’t all bite.”

The weird thing—I mean the really weird thing—is that this afternoon-into-night-into-wee-hours with Clay has got me pursuing lines of logic I’ve never dared pursue before. Not even with Jonathan. Studying Clay’s face in the dim, reddish glow of the Saturn Café, I found myself wondering what a baby would look like with his eyes and my mouth. God, is this my baby clock talking? I spent a whole semester of Fem. Theory my sophomore year writing papers on the topic: how the patriarchy created the baby clock mythology to con women into surrendering to mommyism. At the time I was twenty-one, giddy with the right to get drunk in seedy bars and swivel my hips against this boy and that to frantic techno rhythms. What did I know about biology, except that beer gets you drunk and sex makes you—momentarily at least—something like happy? Now, eight years later, I find myself contemplating how a stranger’s eyes would look in my theoretical baby’s face over a plate of Chocolate Madness.

What do we know about each other? Hardly anything. I know he’s an atheist, owns a record store, graduated from Berkeley and was a drummer in a punk-rock band called Poe when he was fifteen. He knows I love theater, directing more than acting, that I grew up in Calistoga and went to Austin in search of cowboys. Hardly enough résumé fodder has been revealed to warrant the swapping of spit, let alone genetic material. So how can I explain these freakishly domestic fantasies streaking though my psyche like shooting stars?

“You two okay?” Both Medea and I spin round at the sound of his voice. “Still a little skittish, huh?”

“Who, her or me?”

“Both.” He’s standing in the doorway, keeping Sandy from entering by gently nudging her away now and then with one leg. “Come out here, will you? I want you to see something.”

For a fraction of a second I hesitate—Dismembered Arm and Paw Found in Remote Woods—but then I remember Clay’s story about adopting a baby raccoon when he was eight. He named it Zorro and fed it with a bottle, for Christ’s sake. Would a guy like that dismember a girl like me? I extricate Medea from my lap carefully and follow him outside.

He leads me down a short path in the dark, mumbling, “Watch your step.” When we get to the middle of a broad, grassy meadow that smells of yarrow and pine, he looks up and I follow his gaze. Oh, my God. Above us, the stars stretch out in luxurious multitudes, crowding the sky with a million pinpricks of light. I feel suddenly minuscule and happy. I think briefly of Jonathan’s bus packed with all my belongings, reduced now to a charred pile of ash sweeping off on the night breeze. Out here, it doesn’t seem like a big deal. I’ll figure it out. Dwarfed by the enormous carpet of stars, I take a deep breath for the first time in days.

“Smells so good out here,” I say.

“Yeah,” he says. “I think it’s the stars, myself.”

I squint at him in the dark, wanting my eyes to adjust so I can study his eyes. “The stars have a smell?”

“Yeah, I think so. Don’t you?”

I look back up at the layers and layers of them, so vast they surprise me all over again. “Never occurred to me.”

“I think everything’s different in the presence of stars. Food tastes different—”

“Different, how?”

“Saltier, I guess. And sweeter. Music’s different, too—more dreamy, and lonelier. More—” he pauses, and I can see his silhouette clearly now; his face is tilted upward “—more longing in it. And everything takes on this particular scent. You smell it, don’t you?”

“Mmm-hmm,” I say, thinking he’d make a damn fine Romeo if he were ten years younger—he’s got that dreamy-melancholy thing going.

“Wait a second,” he says, and sprints back the way we came. In a minute I hear music floating on the warm September air: acoustic guitar and a melody I’ve never heard, but it’s like I already know it and love it. Some things are like that; sushi tasted totally familiar the first time I put it in my mouth. My parents were choking on the wasabi and I just went on chewing with the gentle smile of someone coming home.

The man singing has one of those resonant, ragged, sexy voices that comes from someplace deep and cavernous in his smoke-filled lungs.

With your measured abandon and your farmer’s walk, with your “let’s go” smile and your bawdy talk.

Clay returns, and he stands so close to me that our arms touch.

“You see? Sounds different under the stars, right?” he asks.

“I haven’t heard it any other way,” I say. “How can I be sure?”

“You’re not a Greg Brown fan?”

With your mother’s burden and your father’s stare, with your pretty dresses and your ragged underwear…

“I could be converted,” I say, smiling. “I’ve just never heard him before.”

“Never heard of—my God. Talk about deprived.”

The skin of his arm feels very warm against mine. Hot, in fact. I lean slightly toward him so that more of my skin touches more of his.

“It’s good you’re not set in your ways,” he says. “If there’s one thing I’m evangelical about, it’s music.” It’s a good thing I refuse to analyze this; if I did, I’d hear the whispered implication that he plans to evangelize me.

“This song’s been haunting me all day,” he says. “I think it might be about you. Tell me the truth, Greg Brown’s in love with you, right?”

“Can’t get anything past you,” I say, but now I want to shut up so I can hear the song and find out what Clay thinks of me. I can only catch certain lines now and then, though, between the crickets and the breeze playfully tousling the pines.

With your pledge of allegiance and your ringless hand, with your young woman’s terror and your old woman’s plans…

“Uh-oh. I just realized,” Clay says. “I’m doing it again.”

“Hmm?” I’m still straining to hear the song. Will your children look at you and wonder, about this woman made of lightning bugs and thunder…take in what you can’t help but show with your name that is half yes, half no.

“I’m being a DJ.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I do this when I’m nervous—try to talk through music. Not even my music. Pathetic.”

“I don’t think it’s pathetic,” I say. “I think it’s sweet.”

He turns slightly, and so do I, and our arm contact becomes my breasts fitting warmly against his chest, and now the sound of his breathing is so close it blends with everything else: the shimmery pine needles and the cricket-frog chorus and the lyrics I can’t quite follow anymore.

He bends down slightly, the shadow of his face moving toward mine, but instead of the expected searching lips, I feel his teeth biting down gently on my lower lip. I suck in my breath.

“I wanted to do that for hours,” he says, his voice thick in his throat.

“Bite me?”

“Mmm. Taste you.”

This guy’s not normal, I think, and a montage of our day unfurls inside my brain with the frenetic pace of time-lapse photography: the bus exploding into ribbons of orange and yellow, the kaleidoscope of the pool balls at the Owl Club, Nick and his jelly-smudged Ramones shirt, Clay feeding me calamari with his fingers. His mouth closes on mine now, and I can taste the day there, the effervescent weirdness of it, the unshakable sensation that I’m being marked by every minute.

You won’t remember the half-open door, or the train that won’t even stop there anymore, for you.

CHAPTER 7

Dawn. Sky is a crazy electric blue. Slivers of it appear when the grass-scented breeze lifts the airy curtains and reveals the morning in triangular slices. I flip over and notice for the first time the circular skylight. Human beings are made for yurts, I think. “Stars make things taste saltier and sweeter.” You won’t remember the half-open door. Clay is positioned in a slightly diagonal tilt; one leg is draped over mine, lips slightly parted as he snores a soft, wheezing prayer to the sleep gods. Medea’s here, curled up close to my head on the foreign pillow, and Dog—what’s her name? Cindy? no, Sandy—is curled up at our feet. Medea opens one eye, checks out proximity of Dog, goes back to sleep. I should be shocked at abruptly finding myself in this tranquil, domestic tableau.

Nothing has ever seemed more natural.

I follow Medea’s lead and collapse back into dreams.

Knock knock knock. Knock knock knock.

Who’s drumming? Jesus, California hippies for you. Always beating their bongos…

Knock knock knock. Knock knock.

“Clay? You awake?” A woman’s voice. Edgy. Irritated.

My eyes pop open. Friend? Has Friend come to visit?

“Clay? Come on, you there? I need your help.” Softer now, asking, “Can I come in?”

I look over at Clay, who is still in the position I saw him in last: stretched corner to corner across the bed, mouth open, snoring. I poke his arm urgently. No response.

“Listen, I know you must be in there, hon.”

Hon?

“I know I said I’d respect your privacy, but the car won’t start and I have a dentist appointment.” Pause. I can hear her swearing softly. “Clay.” Another pause, and then a decision: the doorknob turns. “I’m coming in, okay?”

Oh, God. Paralyzed, clutching sheets to my naked chest. I want to shake snoring Clay awake but I can’t move as the door swings open, followed by a door-frame-shaped blast of sunlight and Woman.

We’re both perfectly still as we stare at each other. She’s so backlit, I can barely make out her features. I can tell only that she’s petite, dark-haired, tightly wound, the type I’d cast as Hedda Gabler: intense, compact, ready for a fight. This is all the data I’m able to gather, blinking into the sunlight, before a whispered “shit” escapes her lips and she backs out the door, slamming it behind her. I hear her footsteps rapidly retreating.

Wanton Tart and Cat Shot by Furious Gabler. Man Says Both Just Friends.

I fall back against my pillow (not my pillow—my pillow is cremated) and close my eyes for a couple of seconds, willing the previous scene to rewind and erase. No use. Instead the scene is in a perpetual loop, playing over and over across my closed lids.

“Clay?”

More snores.

“Hey. Clay?” I’m getting louder, now, shaking him gently but firmly.

“Dad?” he asks, his eyes popping open in alarm. Again, that bizarre, maternal urge stirs in me—some eerie, foreign desire to say “Shh, it’s okay” and kiss him back to sleep. I make a conscious effort to strangle this urge. There will be no shushing or kisses this morning.

All the same, I can’t keep a tiny bit of warmth from my voice. “No, it’s me.”

A little-boy smile takes over his face. “Oh. Ms. Claudia, I presume?” He wraps his arms around me, pulling me down against his chest, and for a second or two I’m so intoxicated by the hot-skin smell of this embrace I nearly forget that his better half is currently rifling through her sock drawer for a .38 special. Resist, Claudia. Resist.

“Listen,” I say, extricating myself from his arms. “There’s been a little incident this morning.”

“Did we wet the bed?”

“Not that kind of incident. An angry-woman-bursts-into-room sort of incident.”

He looks stunned. “Shit. Really?”

“Would I make this up?”

“How do I know?” he counters. “I hardly know you.”

“Yes, well, ditto,” I say. “And obviously, there’s a few things I should have asked. Like, say, ‘Are you married?’” I’m sitting up now, hugging my knees.

“Claudia,” he reaches out to touch my wild nest of hair. “Shit. I’m really sorry.” Not the oh-that-was-just-my-crazy-kid-sister explanation I was praying for.

I stare at him incredulously. “So you are, then? Married, I mean?”

“Well, divorced.” He pauses. “Practically.”

“What does practically divorced mean?”

“We’re legally separated.”

“Is she the Friend in the cottage?” He hesitates before nodding. “Jesus, Clay, you had like nine hours of candid conversation to come clean with me, at least let me know what I’m getting—”

“You never asked.”

Indeed. What can I say? I never asked.

CHAPTER 8

It’s foggy and I’m shivering when Clay drops me and Medea at the Greyhound station downtown. His truck was warm and smelled like cocoa butter. I wanted nothing more than to curl up there before his heater and never leave, but my pride forced me to refuse his offers of a sweatshirt and breakfast. On the drive here, our conversation was limited but revealing.

CLAY: I know this looks really bad.

CLAUDIA: Uh-huh.

CLAY: Really, really bad. I feel like such a shit.

CLAUDIA: Okay…

CLAY: Did you talk to her?

CLAUDIA: Who?

CLAY: Monica.

CLAUDIA: No. It wasn’t exactly an ideal condition for conversation.

CLAY: I’m not in love with her anymore. I want you to understand that.

CLAUDIA: Right. You’re just married to her.

CLAY: Not for very long.

CLAUDIA: And you didn’t mention this earlier because…?

CLAY: I know, I know. This looks really bad. (Repeat)

So here I am, sitting at the Greyhound station with two homeless guys bundled into blankets, one of them reading GQ. Suddenly I’m living the lyrics of every old-timey down-and-out blues number. I’m still wearing this positively crusty-with-human-grime ensemble: orange sundress, sweat-drenched bra, bloodstained underwear, and I’ve little hope of changing into something “fresher” (as my mother would say) anytime soon, seeing as I now own no other clothing. In fact, I now own absolutely nothing.

Oh, God. My favorite Levi’s, reduced to ash. Sea-green cashmere sweater: ditto. Everything—no—I mean everything I ever called my own is now dwelling on another plane of existence.

I plod toward the ticket booth and realize I have no idea where I’m going. My original plan was to camp in the bus until I found a place to live—hopefully before school started. Now the bus is, for obvious reasons, not a reliable dwelling. So I’ve got to figure out where to crash until I can rent my own little shelter from the world. I tell myself this is all very Zen, very neo-Dharma bum and therefore cool (except I keep lugging my cat everywhere—did Kerouac do that?), but when I approach the glassed-in face of the ticket vendor and I look into her kind blue eyes, I find myself fighting off tears. I fumble for some dollars, pulling them from my bra, but they’re so wrinkled and wilted I can’t force them into any semblance of order.

“Morning,” she says. “Where would you like to go?”

“Um.”

She smiles. “Let’s start with the basics—north, south, east or west?”

I manage a weak chuckle. “Give me a second,” I say. “I’ll be right back.”

I sit down on one of the benches and mop at my tears with the back of my hand. I close my eyes and try to breathe. Medea squirms in her box. I open the flaps a crack. Her eyes are glow-in-the-dark as they peer up at me from within her shadowy little cardboard cage. “Shh,” I say. “I’ll get you a nice treat when we get home.” Home.

“Excuse me,” I say to the ticket lady. “Do you have any buses that go to Calistoga?”

She consults a thick directory. “Santa Rosa,” she says. “Is that close enough?”

“I guess it’ll have to be.”

“One way or round trip?”

“One way, please.”

“That’ll be eleven dollars.”

I hand her a limp twenty and she counts me out my change.

“You going to check out those mud baths?”

“God, no,” I say. “Just going home.”

Calistoga’s only about three or four hours from Santa Cruz by car, but by bus it’s a twelve-hour saga. I take the Greyhound to Santa Rosa, then another bus from there, and finally walk the last eight blocks to my father’s house. By the time Medea and I arrive on his doorstep we’re exhausted and snappish, having schlepped across three counties in raunchy-smelling clothes with a full cast of trying characters, including an ancient man in a wheelchair who, having mistaken me for his dead wife, wouldn’t stop trying to hold my hand, and a wiry little elf of a bus driver who threatened to kick us off when he heard Medea mewing.

Over the course of the day I’ve developed a serious obsession with showering. That first blast of cool water on my chest, leaning in to soak my face, then my hair; the gentle massage of liquid needles against my scalp. The whole experience has become my nirvana—a longed-for state I can almost taste but never achieve.

It would have been quicker to go to Mom’s in Mill Valley, but thinking of her latest husband and her spoiled, Britney Spears-clone stepdaughter makes me want to yuke, so I opt for Dad’s.

“Claudia,” my father says, opening the door. “You’re—wow. You’re here.”

“Yeah. Sorry I didn’t call.” We just stand there awkwardly, surveying each other, and for an agonizing second I think he’s not going to ask me in. Then, as if reading my thoughts, he steps back and gestures toward the living room a little too eagerly, like a waiter in an empty restaurant. “Come in, come in,” he gushes. And then, his tone going puzzled again, “You’re really here.”

“Didn’t you get my e-mail?”

He just looks confused. “Oh, you know me—I haven’t really adjusted to all of this technology stuff.”

“Dad, can I let Medea out? She’s been in this stupid box all day.”

“Who?”

But I’m already releasing the poor thing; she circles my legs, blinking into the light, looking a little crazed and disoriented. “My cat,” I say, and sigh. “It’s been a very long day.” I say that a lot, lately.

He squints down at her as she rubs against his shin. “Hello, kitty,” he says doubtfully. “What’s her name?”

“Medea.”

“Oh,” he says, stiffly. “Hello, Maria.”

And then he starts to sneeze. Five times. With increasing volume and violence. Jesus, what is it with men and cats? Clay’s the only guy I ever met who didn’t practically disintegrate in the face of a little cat fur. No. Don’t even think about Clay Parker.

“Ah-ah-ah-allergic,” my father manages to articulate between sneezes.

“Okay. I’m sorry. Um, can I put her in the guest room for now? I’d put her out, but she’s so disoriented I’m afraid she might wander off—”

“Garage,” he says, yanking a handkerchief from his back pocket and sneezing some more. So off she goes, into the garage, mewing in protest until I fetch her a bit of tuna fish and a saucer of milk. I sit there with her for a while, playing absently with her tail and watching her eat, enveloped in the cool, cathedral-like stillness of my father’s garage. As my eyes adjust to the shadows, I gaze around at the meticulously organized shelves and file cabinets, the worktable with tools hanging on hooks, arranged categorically: drills here, saws there. It occurs to me that these may even be alphabetized, which I find more than a little depressing. The air is scented not with the usual grease-and-grime smell of most people’s garages, but with my father’s favorite all-purpose cleaner for twenty years now: Pine-Sol. Parked in its usual place—dead center—is Dad’s 1956 Dodge Plymouth convertible. It gleams with spotless pride in the dark, never having known a dirty day in its life.

I find Dad in the kitchen, cutting up celery. The house, like everything in my father’s life, is so clean you could eat off any surface, including the tops of high cabinets and the icy-white linoleum floor. He bought a tract home soon after I moved to Austin—one of those creepy, cookie-cutter models that scream “No Imagination.”

“So,” he says, handing me a glass of milk with ice in it. I don’t usually drink milk, but I sip politely, anyway. “How long are you here for?”

“You mean, here, at your house? Or…?”

“When do you go back to Texas?”

“Pop, listen. I got a job in Santa Cruz.”

He smiles. He has very white teeth, perfectly straight; my mom says he was still wearing braces when they got married. “You’ve got a Santa Cruz in Texas? Isn’t that funny. I guess all those saints really made the—”

“Santa Cruz. California, Dad. I got a job at the university.”

He stops cutting celery and stares at me a moment through his horn-rimmed glasses. He’s got very light blue eyes and a face that is harder to read than any face I’ve ever encountered. He goes back to slicing. “Are you serious?”

“Yes. Of course I’m serious.” I drink more of my milk and try not to think about the report I read once about cows in America being so mistreated and diseased that they get loads of pus in the product. Eugh. I put the glass down.

“What about your boyfriend? Is he moving here, too?”

“What boyfriend?” I’m unable to stop myself from this perverse response. Something about his calm, measured slicing of celery and his luminous white tile countertops are getting on my nerves. I remember now why I’ve only seen my father five or six times in the past ten years.

“Jason, wasn’t it?”

I shift my weight and look at the ceiling. “Jonathan. We broke up.”

“Oh. I see.” He nods at the celery in a cryptic fashion.

“Anyway,” I say, dumping the rest of my milk in the sink as inconspicuously as I can, “I’m moving to Santa Cruz. I just need to get a car and a place to live.” I stand there, staring at the ice cubes in the sink. I run the water so he won’t see the milk I dumped out, and that makes me remember the bathing fantasy I’ve been fueled by all day. I want to cry with relief when I think of my father’s hotel-sterile bathroom. “Can I take a shower?”

“Oh, sure, honey. Sure.” He’s more enthusiastic about this possibility than anything I’ve told him so far. “Extra towels in the hall closet.” Oh, God. My father’s white, fluffy, dryer-scented towels. I almost throw my arms around him in ecstasy. Then I remember that I don’t have anything to change into, and the thought of putting this wretched outfit on yet again turns my stomach.

“You think I could borrow a T-shirt, maybe some shorts?”

He lets out a snort of awkward laughter. “Honey, where’s your suitcase?”

“It’s a really long story. Just—anything. Sweats, old jeans, whatever you’ve got.”

“Well, okay. I’ll see what I can find. They’ll be in the guest room.”

“Thanks, Pop.” I walk over to him and, before I can get nervous or weird about it, kiss him on the cheek. “I really appreciate being able to come here.”

“Oh,” he says, smiling nervously, never taking his eyes from the celery. “Well.” And then, when I’m walking down the hall to the bathroom, he calls to my back, “You know you’re welcome, sweetie, anytime.” I think he means it, but something about the effort in his voice makes me want to cry.

CHAPTER 9

To do:

1) Buy fantastic, sexy, dependable, movie-star-quality car for under three hundred dollars.

2) Do not think about Clay Parker. If absolutely must think of yurt experience, think of WIFE and add SELF at wrong end of .38 special.

3) Find adorable, sexy, movie-star-quality pad for under five hundred dollars.

4) When did I become a home-wrecker? Argh.

5) Join gym. Go to gym. Thighs look like molded Jell-O.

6) Make friends.

7) DO NOT THINK ABOUT HIM.

8) Transform self from hideous, kinky-haired, irresponsible car-thief home-wrecker into elegant, scarf-wearing professor. (Idea: highlights?)

For several days I use my father’s house as the base of operations while I continuously flip-flop between wild bursts of effort to get my life together and bouts of total despondency, during which I lie flat on my back in the guest room, stuffing my face with Pringles and watching cheesy Hugh Grant videos. This manic-depressive stretch hardly fulfills my hopes of returning triumphantly to California and emerging like a phoenix from my troubled past.

I grew up here, in Calistoga, and coming home is like facing a firing squad of ghosts. I know loads of people are carrying around childhoods more miserable than mine—hell, most of my friends’ horror stories make my family look like the Cleavers—but all the same, I get restless here, enmeshed in the world that formed me.

Luckily, my father doesn’t live in the house I spent my first decade in anymore. Most of my worst associations are stuck there, in the idyllic little Victorian on Swan Street where we lived before my parents divorced. That house is where my parents fought their worst battles, almost always silent ones that went on for weeks at a time. They were both very good at refusing to speak to each other. I often felt like a modern-day sitcom character who finds herself in the midst of a silent film. The easiest way to explain their marriage is by cutting to the chase: they didn’t love each other. Not in the days I can remember, anyway. And though my mother was in every cosmetic way the ideal housewife, she maintained an air of aloofness, an icy edge that, paired with my father’s lack of communication skills, made my growing up years chilly and lonely.

Calistoga isn’t a bad place to grow up, though it’s pretty small and confining when you’re a hormone-crazed teen. It’s wedged between two smallish mountain ranges, one of several little tourist towns in Napa Valley that’s beautiful and pristine and increasingly saddled with this “wine country” label, which attracts the most anal-retentive blue bloods in the country. Unlike a lot of other towns around here, Calistoga always maintains a kind of redneck Riviera not-quite-thereness, though, which I’m secretly glad about. The tourists who settle for our town are the ones who can’t quite afford our posher neighbors, though we do our best to keep up appearances. We’ve got these natural hot springs and more spas than citizens; people flock here from Des Moines and Denver and God Knows Where to sit around in huge tubs of “volcanic ash” and scalding water, imagining that all the toxins they’ve been stuffing themselves with for fifty years will magically evaporate and they’ll emerge like radiant infants. Truth is, half of the time the volcanic ash is really just garden-variety dirt, and once I even witnessed the use of cement.

I know more than I care to about the Calistoga spas—I’ve worked in just about all of them, though in the ten years I’ve been gone they’ve probably shuffled around a bit. When I was fourteen I started raking mud and fetching cucumber water for the needy, red-faced tourists. Within a few years I got some training and moved up to massage therapist; at seventeen I was the only girl I knew making twenty bucks an hour plus tips. It was a good enough gig. People treated you like a cross between a doctor and a prostitute, which I always found amusing.