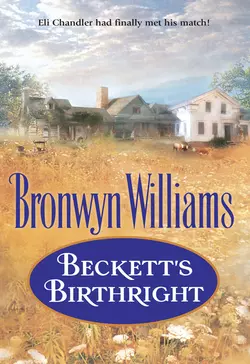

Beckett′s Birthright

Bronwyn Williams

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 465.10 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Eli Chandler didn′t need a redheaded wildcat to complicate his life. What with a fiancée gone missing and a wily gambler on the loose, the ranch manager had enough on his plate. So why did he hunger after the boss′s daughter, with a newly whetted appetite for love?Delilah Jackson could appreciate that. Just as she could appreciate the shocking way he made her feel without even trying–reminding her she was a woman first and a rancher second!