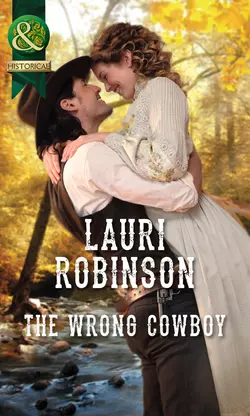

The Wrong Cowboy

Lauri Robinson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 382.20 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: One mail-order bride in need of rescue! All the rigorous training in the world could not have prepared nursemaid Marie Hall for trailing the wilds of Dakota with six orphans. Especially when her ingenious plan—to pose as the mail-order bride of the children’s next of kin—leads Marie to the wrong cowboy! Proud and stubborn, Stafford Burleson is everything Marie’s been taught to avoid. But with her fate and that of the children in his capable hands, Marie soon feels there’s something incredibly right about this rugged rancher and his brooding charm.... “A delightful western…humor, realism and sweet emotion.” —RT Book Reviews on Inheriting a Bride