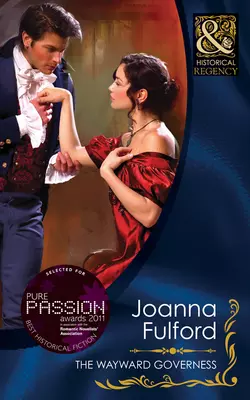

The Wayward Governess

Joanna Fulford

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 387.74 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘I will not become a rich man’s plaything! ’ Threatened with an unwelcome marriage, Claire Davenport flees to the wilds of Yorkshire. There, the darkly enigmatic Marcus Edenbridge, Viscount Destermere, comes to her rescue – and employs her as governess to his orphaned niece. Finding his brother’s killer has all but consumed Marcus until Claire enters his life. Her innocent beauty and quick mind are an irresistible combination, but she is forbidden fruit.It’s not until their secrets plunge them both into danger that Marcus realises he cannot let happiness slip through his fingers again…