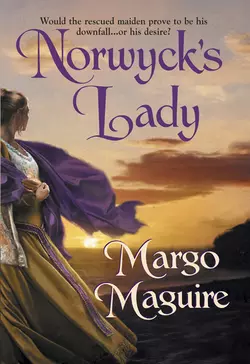

Norwyck′s Lady

Margo Maguire

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 382.20 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Women Could Not Be TrustedBartholomew, Earl of Norwyck, had well learned that bitter lesson from his traitorous first wife. What, then, should he make of «the Lady Marguerite,» a mysterious beauty who claimed ignorance of her true identity? Was she an enemy sent to destroy him–or an angel come to heal his wounded soul?Bartholomew had saved her from a shipwreck, only to dash her upon the rocky shores of his darkest suspicions. But if Marguerite were truly one of his blood-sworn enemies, how then to explain the desire that pulsed between them–threatening to engulf them in a heat as fierce as any flame?