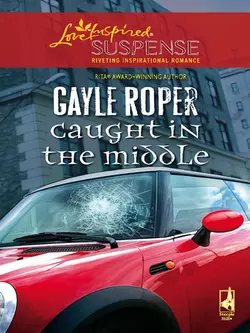

Caught In The Middle

Gayle Roper

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Amhearst, Pennsylvania, was just the kind of place for new beginnings for brokenhearted reporter Merry Kramer.But she soon discovered danger lurked behind the holly bushes when a dead body turned up in her car! The trouble didn′t end there–gunshots, attacks and a handsome new friend who might not be what he seemed.Surrounded by suspects, Merry would have to use all her investigative skills to keep from becoming front-page news–as the killer′s next victim.