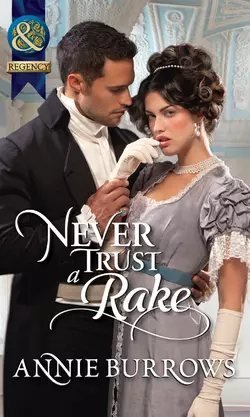

Never Trust a Rake

ANNIE BURROWS

RUMOUR HAS IT THAT THE EARL OF DEBEN, THE MOST NOTORIOUS RAKE IN LONDON AND IN NEED OF AN HEIR, HAS SET ASIDE HIS PENCHANT FOR MARRIED MISTRESSES AND TURNED HIS SKILLED HAND TO SEDUCING INNOCENTS!But if Lord Deben expects Henrietta Gibson to respond to the click of his fingers he’s got another think coming. For she knows perfectly well why she should avoid gentlemen of his bad repute:1. One touch of his lips and he’ll ruin her for every other man.2. One glide of his skilful fingers to the neckline of her dress will leave her molten in his arms.3. And if even one in a thousand rumours is true, it’s enough for her to know she can never, ever trust a rake…

Praise for Annie Burrows:

THE EARL’S UNTOUCHED BRIDE ‘Burrows cleverly creates winning situations and attractive characters in this amusing romance. A desperate bride, a hostile husband and an outrageous proposal will win your attention.’ —RT Book Reviews

A COUNTESS BY CHRISTMAS ‘Burrows has wonderfully developed characters and accurate historical settings, which make for a compelling read from beginning to end. This is a beautiful, poignant, sensual story of two lonely hearts finding each other at last.’ —RT Book Reviews

‘Last chance, Miss Gibson. Stop me now, or I will kiss you. And I promise you, if I do that, you will never be the same again.’

She wasn’t the same already. She had never, ever thought about what a man would look like naked, in bed. Or felt her lips tingle with expectancy. Nor had her heart raced like this while she was sitting completely still. And all he’d done so far was talk about kissing.

Heavens, no wonder women were queuing up for the privilege of taking him as a lover.

‘Do you wish to continue?’

‘Wh … what?’

‘With your lesson? Do you wish me to take it to its conclusion?’

Lesson. She blinked.

‘You should let your lips relax,’ he instructed her. ‘Perhaps part them a little for me. Moisten them, if you wish. By all means close your eyes.’

He was lowering his head towards her. Any second now …

‘I find that absence of sight heightens the other senses.’

Immediately she screwed her eyes tightly shut. Though it wasn’t about heightening her senses, since hers were pretty over-stimulated already, so much as hiding. She did not want him looking into her eyes when they kissed in case he saw …

What? That she could never have imagined feeling like this?

About the Author

ANNIE BURROWS has been making up stories for her own amusement since she first went to school. As soon as she got the hang of using a pencil she began to write them down. Her love of books meant she had to do a degree in English literature. And her love of writing meant she could never take on a job where she didn’t have time to jot down notes when inspiration for a new plot struck her. She still wants the heroines of her stories to wear beautiful floaty dresses and triumph over all that life can throw at them. But when she got married she discovered that finding a hero is an essential ingredient to arriving at ‘happy ever after’.

Previous novels by Annie Burrows:

HIS CINDERELLA BRIDE

MY LADY INNOCENT

THE EARL’S UNTOUCHED BRIDE

CAPTAIN FAWLEY’S INNOCENT BRIDE

THE RAKE’S SECRET SON

(part of Regency Candlelit Christmas anthology) DEVILISH LORD, MYSTERIOUS MISS THE VISCOUNT AND THE VIRGIN (part of Silk & Scandal Regency mini-series) A COUNTESS BY CHRISTMAS CAPTAIN CORCORAN’S HOYDEN BRIDE AN ESCAPADE AND AN ENGAGEMENT GOVERNESS TO CHRISTMAS BRIDE (part of Gift-Wrapped Governesses anthology)

Also available in eBook format in Mills & Boon

HistoricalUndone!:

NOTORIOUS LORD, COMPROMISED MISS

HIS WICKED CHRISTMAS WAGER

Do you know that some of these novels are also available as eBooks? Visit www.millsandboon.co.uk

Never Trust a Rake

Annie Burrows

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

With thanks for all the help and support

the Novelistas of North Wales provide.

You are a great bunch of ladies.

Chapter One

Ye Gods, he’d known it would not be easy, but he hadn’t expected them all to be quite so predictable.

Lord Deben strode out on to the terrace, deserted since the night air was damp with drizzle, made it to the parapet and leaned heavily on the copingstone, where he drew in several deep breaths of air blessedly unadulterated by perfume, sweat and candle grease.

First to run true to form had been tonight’s hostess, Lady Twining. Her eyes had practically popped out of her head when she’d recognised exactly upon whose arm the Dowager Lady Dalrymple was leaning. He had only ever once before had anything to do with a come-out ball, and that had been his own sister’s—a glittering affair which he’d hosted himself some four years ago. He could see Lady Twining wondering why on earth he had suddenly decided to accompany such a stickler for good form to such an insipid event, held in the home of a family who would never aspire to be part of his usual, racy set.

While they had slowly mounted the stairs, he’d watched her rapidly working out how to deal with the dilemma his attendance posed. She could hardly refuse to admit him, since she’d sent his godmother an invitation and he was evidently acting as her escort. But, oh, how she wanted to. She clearly felt that letting him in amongst the virtuous damsels currently thronging her corridors would be like opening the henhouse door to a prowling fox.

But she didn’t have the courage to say what she was thinking. And by the time he’d arrived at the head of the receiving line, it was all what an honour to welcome you into our home, my lord, and we did not think to have such an august presence as yours …

No. She had not actually said that last phrase, but that was what she’d meant by all that gushing and fluttering. The presence of a belted earl was such a social coup for her that it far outweighed the potential danger he posed to the moral tone of the assembly.

And as for those assembled guests—his lip curled in utter contempt. They had divided neatly into two camps: those who reacted solely to his reputation by clucking and fluttering like outraged hens in defence of their precious chicks and those, he grimaced, with an eye to the main chance.

He’d felt their beady eyes following his progress into the house. Heard the whispered swell of speculation. Why was he here? And with Lady Dalrymple, of all people? Was it a sign that this Season he was at last going to do his duty to his family and take a wife?

On the outside chance that the most notorious womaniser of his generation, the most dangerous flirt, was actually going to look about him for a woman to take her place at his side in society, as his legally wed countess, the most ambitious amongst them had promptly begun elbowing each other aside in their determination to thrust their simpering charges under his nose.

The fact that they’d guessed correctly didn’t make their approaches any less repellent. Which was why he would have to attend more events such as this and endure the vapid discourse that passed for conversation and the gauche mannerisms … and sometimes even the spotty complexions. How else could a man be absolutely sure that his first child, at least, was of his own get unless he married a girl who’d only just emerged from the schoolroom? And the duty he owed his proud lineage made that an absolute imperative.

But did they really think he’d propose to the first chit he met, at the first event he attended since he’d made up his mind it was time, and past time, he knuckled down to the fate his position made inescapable?

He leaned back and tilted his face to the rain. It managed to cool his skin, even if it could do nothing to soothe the roiling bitterness churning in his guts. Nothing could do that.

Unless … He stilled, as the most fantastic thought occurred to him. He didn’t think he could face many more such events as this. And what was there to choose between all those pallid, eager, young females, after all? Why the hell shouldn’t he just propose to the very first chit to cross his path when he went back inside? That would at least get the whole unpleasant business over and done with as quickly and painlessly as possible.

What would it take—a year out of his life? Propose to one of those girls who’d been paraded before him like brood mares at Tattersalls. Get the banns read, go through the travesty of a ceremony, bed her, then keep on bedding her until he could be certain she was increasing. Hope that the child was a boy. Then, with the succession sorted, he could return to his carefree existence and she could …

He sucked in a short, sharp breath, bowing his head again as he considered what his wife would get up to, left to her own devices.

Anything. Anything and everything. Nobody knew better than he just how far bored young matrons would go in the pursuit of sexual adventure.

With an exclamation of impatience he pulled his watch from his waistcoat pocket and turned to catch the light from the ballroom windows so that he could check the time. His brow raised in disbelief. Had he only been in this house for thirty minutes? It could be hours before Lady Dalrymple was ready to leave. She would want to watch the dancing, gossip with those of her cronies who were present and take supper.

So be it. His mouth twisted with distaste. He had to fill in the time somehow, so it might as well be following his impulse to deal with the marriage situation as swiftly and cleanly as possible. He would return to the ballroom and ask the first girl to cross his path to dance with him. If she accepted, and if he didn’t find her too repulsive, he would locate her father and start talking settlements.

There. The whole abominable, damnable thing settled. He would not even have to alert the ton to his intent by setting foot in that hellhole known as Almack’s.

And yet, when he replaced his watch in his pocket, his feet remained welded to the spot. And his gaze stayed fixed straight ahead, though his eyes were not seeing the dampening gardens below the terrace, but the abyss into which he was about to throw himself.

It would not matter if he could not grow to like the anonymous chit who waited for him inside that house very much, as long as he could contemplate bedding her for the requisite amount of time to get an heir. If he didn’t grow fond of her, she wouldn’t have the power to hurt him. Humiliate him. He could watch her carrying on her love affairs with the same kind of amused indifference displayed by all the husbands he’d cuckolded over the years. Whose bored, dissatisfied wives had been actively seeking younger, more energetic men to provide them with the spice their dutifully contracted marriages so singularly lacked.

Within the bounds of such a lukewarm arrangement, he might even be able to tolerate her offspring. Perhaps even treat them with kindness, rather than calling them bastards to their face. And they’d think of each other as brothers and sisters, and care for and support each other, instead of …

A swell of music issuing from the ballroom pulled him abruptly from the maelstrom of negativity that always churned through him whenever a stray thought escaped its confines and crept back towards his childhood.

He turned slowly, annoyed to have his brief interlude of solitude interrupted, though he hadn’t expected to see a female silhouette in the doorway that led back to the house.

‘Why, Lord Deben!’

The girl gasped and raised her hand to her throat in a dramatic gesture, intended, he supposed cynically, to betoken surprise.

‘I did not think anyone else would be out here,’ she said, glancing along the length of the otherwise deserted terrace and back.

‘Why, indeed, would anyone venture forth in such inclement weather?’

Undeterred by the dryness of his tone, she advanced a step or two and giggled.

‘I should not be out here with you, all alone, should I? Mama says you are dangerous.’

Now that she was closer he could see she was quite a pretty little thing. Good features, clear skin, expensively and fashionably clad. And well used to male attention, to judge from the way she was preening under his leisurely, not to say insolent, perusal of her assets.

‘Your mama is correct. I am dangerous.’

‘I am not afraid of you,’ she said, sashaying right up to him. She came so close that the perfume she wore wafted to his nostrils from her hot little body. She was breathing hard. She was excited. A little nervous, too, but mostly excited.

‘You have never been known to harm a virtuous damsel,’ she said breathily. ‘Your reputation has all been gained with young matrons, or widows.’

‘Your mama should have warned you that it is not the thing to discuss a man’s amours with him.’

She smiled. Knowingly.

‘But, Lord Deben,’ she murmured, sliding one hand up the lapel of his jacket, ‘I am sure you want your future wife to understand these things. To be understanding …’

He gripped her hand and detached it from his clothing, filled with a gut-deep revulsion.

‘On the contrary, madam, that is the last thing I want from the woman I shall marry.’

It was no good. He was more like his father than he’d thought. Even if he took the greatest care never to fall in love with his own wife, he wouldn’t be able to bear the thought of her being understanding. Of expecting him to carry on as though he was still a bachelor, so that she could enjoy her own sexual adventures.

In short, of becoming a cuckold.

‘You had better return to the ballroom. As you yourself said, it is quite improper of you to be out here, alone, with a man like me.’

She pouted. ‘It is absurd of you to preach propriety, when everyone knows you have never had any time for it.’

Then, in a move so swift it took him completely by surprise, she flung both arms about his neck.

‘God dammit, what are you about?’ He reached up and tried to disentangle himself from her hold. He managed to prise one hand off, but then she dropped her fan, leaving her other hand free to find purchase. When he stepped smartly back in a more determined effort to evade her grasping hands, she clung tighter, so that he found himself dragging her with him.

‘Let go of me, you impudent baggage,’ he growled. ‘I do not know what you think you will achieve by flinging yourself at me like this, but …’

There was a shriek. Light flooded the terrace as the doors from the house burst open. The girl who had been clinging so tenaciously slumped against him, pressing her cheek to his chest.

‘Lord Deben!’ A well-built matron stalked towards him, her jowls quivering with indignation. ‘Let go of my daughter this instant!’

He still had his hands on her wrists, from when he’d been trying to prise her off. As he attempted to push her upright, she gave a little moan and arched theatrically backwards, as though in a faint. Instinctively, he caught her as she began to fall. And though part of him would have dearly liked to let her slump into a crumpled heap on the damp flagstones, another part of him knew that were he to give in to such a base instinct, it would only make the situation look worse for him.

At any moment, another person might take it into their heads to come outside, and what would they see? The wicked Lord Deben standing over the prone body of a shocked, half-ravished innocent? Or the wicked Lord Deben standing with the swooning victim of his attempted seduction clasped in his arms? With the indignant mother demanding the release of his supposed victim?

Whichever tableau they would see, the outcome would be the same. These two females would expect him to make reparation by marrying this scheming little baggage.

He had never been so angry in his whole life. Caught in the kind of trap a greenhorn should have seen coming. And on his first foray into the world of so-called innocents! How could he have so woefully underestimated the predatory nature of womankind? He’d dismissed those virtually indistinguishable white-clad girls in the ballroom as vapid, brainless ciphers. But this girl had a quick mind. And an immense amount of ambition. He was the wealthiest, youngest, most highly ranking man she was ever likely to get within what he guessed was her limited social reach. And she had taken ruthless advantage of his momentary lapse of concentration to compromise him. She didn’t care a whit for his character. Or have a qualm about marrying a man she believed was incapable of fidelity. In fact, she’d told him she would condone it.

What was worse, the chit was not to know he was, in actual fact, looking for a wife. For all she knew, he was still an obdurate rake.

And yet she had persisted in setting out to ruthlessly snare him.

Cunning, ambitious, ruthless and amoral. If his mother were still alive, she would have seen this girl as a kindred spirit.

‘It is quite obvious what has been going on out here,’ said the girl’s mother, drawing herself up to her full height. Then, just as he’d expected, she said, ‘You must make amends.’

‘Offer marriage, you mean?’ That did it. He no longer cared if the old besom did think him ungallant. He thrust her clinging daughter from him with such determination she tottered a few steps and had to clutch at her mother to prevent herself tripping over.

Had he really been toying with the idea of proposing to the first apparently eligible female to cross his path? Was he mad? If he married a creature like this one, history would repeat itself, with the added twist that he would never be entirely certain who had fathered any of the children for whom he would be obliged to provide.

He leaned back against the balustrade and folded his arms. He was just about to inform them that no power on earth would induce him to offer this girl his name when another voice cried out, ‘Oh, please, it is not what it looks like!’

The three of them at his end of the terrace whirled towards the shadows at the far end, from whence the voice had emanated.

He could just make out a slender female form wriggling out from between two massive earthenware planters, behind which she had clearly been concealing herself.

‘For one thing,’ the still-shadowed girl said, reaching down to free her gown from some unseen obstruction, ‘I was out here the whole time. Miss Waverley was never alone with Lord Deben.’

Having freed her skirts, she straightened up and walked towards them. She hovered on the fringe of the pool of light in which they stood, as though reluctant to fully emerge from the shadows. But he’d glimpsed moss smearing the regulation white of her gown as a corner of it had fluttered into the light. And there was what looked like dried leaves caught in the tangled curls which tumbled round a pair of thin shoulders.

‘That’s all very well,’ the outraged mother of the scheming Miss Waverley, as he now knew her to be named, put in, ‘but how did he come to have her in his arms?’

Miss Waverley was still clinging to her mother with the air of a tragedy queen, but on her pretty face he could see the first stirrings of alarm.

‘Oh, well, she …’ The dishevelled girl hesitated. She darted a look towards the worried Miss Waverley, then drew herself upright and looked the older woman straight in the eye. ‘She dropped her fan. And then she sort of … stumbled up against Lord Deben, who naturally prevented her from falling.’

Well, she’d certainly presented the whole sequence of events in such a way as to put an entirely different complexion on the matter. Without telling an outright lie.

In fact, it had been very neatly done.

He pushed himself away from the balustrade and took the two paces necessary to reach the fan, which he bent down and retrieved.

‘No gentleman,’ he said, having decided to take his cue from the girl who, for some reason, reminded him of autumn personified, ‘not even one with a reputation as tarnished as my own, could have permitted such a fair creature to fall,’ he said, returning the fan to the set-faced Miss Waverley with a flourish. He had no idea why the Spirit of Autumn had decided to put a stop to Miss Waverley’s scheme, but he was not about to look a gift horse in the mouth.

Miss Waverley’s mother was looking pensively at the uneven edges of the damp flagstones on which they stood.

Miss Waverley’s eyes were darting from him to the girl who had emerged from the shadows. He could almost see her mind working. It was no longer a case of her word against his. There were two people prepared to swear nothing untoward had occurred here this night.

‘Sir Humphrey should get these flags attended to, don’t you think?’ He smiled frostily at the girl who had attempted to compromise him. ‘Before somebody comes to grief. But at least I have the satisfaction of knowing that you have not come to any lasting hurt from this night’s little encounter.’

She flung up her chin and glowered at him.

Her mother, however, was more gracious in defeat.

‘Oh, well, I see now how it was, of course. And I do thank you for coming to my daughter’s aid, my lord. Though why she was out here with Miss Gibson, I cannot begin to imagine. She is not our sort of person. Not our sort of person at all.’

The matron shot the bedraggled nymph a look of contempt.

Did he imagine it, or did she shrink from the scrutiny, as though she was half-thinking of ducking behind the ornamental urns again?

‘Nor can I imagine how my dear Isabella has come to be on such intimate terms with her. Really, child,’ she said, addressing her daughter, whose mouth was pouting sulkily, ‘I cannot think what on earth possessed you to accompany a person like that out here, where you might have soiled your gown. Or caught a chill. How on earth,’ she said, rounding on the hapless Miss Gibson, ‘did you manage to persuade my daughter to come out here? And what were you doing, hiding at the end of the terrace down there, leaving my daughter alone with a gentleman? Have you no notion how improper your action was? How selfish?’

Though he couldn’t help wondering himself how Miss Gibson would answer that barrage of questions, he had his own list, which were far more pertinent, given that he knew what had actually occurred.

The one which was uppermost, however, was to wonder why she had not taken the chance to expose Miss Waverley for the scheming jade she was, if she was so keen to put a spoke in her wheel. Her description of the sordid little scene had been so neatly wrapped up that Miss Waverley would walk away from this encounter with her reputation untarnished. Yet concern for Miss Waverley’s reputation could not have been what prompted her. She’d come out of hiding before he told them he would never offer her his name, no matter what tales they told. His reputation was already black as pitch, so he had nothing to lose. But the Waverley chit would most definitely have got her just deserts if this pair of designing females had attempted to cross swords, socially, with a man of his standing.

All Miss Gibson had needed to do, so far as she was concerned, was to stay concealed behind her plant pots and wait for them all to go away. Had she acted from friendship, then? Had she wanted to save a friend from a disastrous marriage?

No … he didn’t think that was it either. Miss Waverley had, at no point, looked as though she felt anything … friendly about the girl who’d thwarted her ambition. She certainly had not expected her to be out here. She had scanned the terrace for witnesses before staging her attempt to compromise him. And been furious when the Gibson girl had emerged and scotched her plans to bag herself an earl.

Enemies, then? No … from what the mother had said they barely mixed in the same social circles. Which meant they were not likely to have had opportunity to become either enemies, or friends.

Whichever way he looked at it, he kept on returning to the same unsettling conclusion. Her actions had nothing to do with Miss Waverley at all.

She had been attempting to rescue him.

He leaned back against the parapet once more, one hand on either side of him, and watched her in fascination. She was not making any attempt to defend herself while Miss Waverley’s mother rang a peal over her. She scarcely seemed to notice either the tirade, or the poisonous glances Miss Waverley kept darting at her.

She was just standing there, shoulders slumped, as though she simply did not care what anyone thought of her, or said of her. As though she wasn’t even fully attending to the vitriol being poured upon her innocent head.

Right up until the moment when Miss Waverley’s mother said, ‘But, then, what can one expect from somebody hailing from such a family as yours?’

At that, the change which came over her was remarkable. She lifted her head and stepped forwards, so that she was for the first time fully illuminated by the light streaming from the ballroom windows. All the colours of autumn glowed in her wild tresses. Rich conker browns, threaded with gold and russet of leaves on the turn. And her demeanour was so fierce, it was like witnessing a storm whipping up out of nowhere, blasting away all shreds of one of those drear November mornings which so depressed him.

‘One can expect honourable behaviour,’ she said. ‘I was concealing myself only because I did not wish anyone, especially not a gentleman, to see that I had been crying.’

Now that he could believe. Miss Gibson did not weep prettily. Her nose, which was a shade too large for her rather thin face, was red and running. Her cheeks were mottled and streaked with what looked like not only tears, but horrifically like the effusions from that abomination of a nose.

It made it all the more remarkable for her to have exposed herself to view, in order to intervene in the affairs of two people who were neither her friends, nor, in his case, even a remote acquaintance.

‘I might have known,’ the matron snapped. ‘I hope you are thoroughly ashamed of yourself, young lady. You see what comes of giving way to such a vulgar display of emotion? Not only do you look an absolute disgrace, but your selfish, wilful behaviour has exposed my own, blameless daughter to a situation that might very easily have been misinterpreted!’

Miss Gibson clenched her fists. She looked at the blameless Miss Waverley and took a breath. She was just about to blurt out the truth that would send shock waves rippling through the tranquillity of Miss Twining’s come-out ball, when he saw a look of chagrin cross her face.

Ah. She had just worked out that she could not now tell the complete truth without exposing herself. That was what happened when a woman began to spin a web of lies. She only had to put one foot wrong, to run the risk of becoming hopelessly enmeshed herself.

At least she had the intelligence to see it. She closed her mouth, lifted her chin and regarded the mother in stony-faced silence.

He felt his lips twitch as the gale blew itself out. Really, this was better than a play.

It was perhaps unfortunate that Miss Gibson glanced at him at the exact moment he began to see the humour in the situation. She caught his amused expression and returned it with a scowl that could have curdled milk.

‘Well,’ said the matron, who had missed the exchange of glances, because she’d been busy placing a comforting arm about her thwarted daughter’s shoulders. ‘I can see that you were motivated by the kindness of your heart, my dear, but really, it would have been better to have sought out Miss Gibson’s chaperon and let her deal with it.’

His brief foray into amusement at the absurdity of it all was over. The matron’s attitude was almost as offensive as that of her daughter. Here was a young female, so distressed that she’d run outside to give way to her emotions, and all she was getting was a lecture. It was not right. Somebody ought to be offering her some comfort. After all, females did not weep with such abandon, not in private, without having very good reason. They must know that, surely?

He looked at the mother. At Miss Waverley herself. And frowned.

He did not have much in the way of empathy for the sensibilities of females, but he was clearly the only person out here who felt even the tiniest scrap of it towards the bedraggled Miss Gibson. Not that he would dream of attempting to deal with her personally. He’d never had any success soothing weeping females. On the few occasions he’d attempted to offer consolation to one of his sisters when indulging in a fit of tears, his brand of rational argument had thrown them into something bordering on hysterics.

She needed a sympathetic female. The chaperon that the Waverley woman had mentioned—that was the woman who would know how to deal with her.

He pushed himself off the balustrade. ‘Allow me to rectify that error,’ he said, ‘by performing that office this very minute. If one of you would be so good as to furnish me with her name?’

‘Oh,’ said the matron with a sneer, ‘she is a Mrs Ledbetter. I dare say you would not know her, my lord. Indeed, I cannot think how a woman of her station in life came to secure an invitation to an event such as this.’

He smiled. ‘Indeed. One attends private balls in the expectation of only encountering a better class of person. Mrs Waverley, is it?’

‘Lady Chigwell,’ she simpered.

‘Lady Chigwell,’ he replied, with a bow of acknowledgement. As he straightened up, he caught Miss Gibson’s eye and gave her a wink. But if he had thought she might have relished the thinly veiled snub he had just administered, he was disappointed, meeting only disapproval in her gaze.

Perhaps she had not understood the gesture he had made on her behalf.

‘Miss Gibson,’ he said, closing the distance between them so that he could take her hand, ‘may I tell Mrs Ledbetter you will wait for her out here?’ In an undertone, he added, ‘What does she look like?’

Miss Gibson blinked up at him with eyes that, at close quarters, he could see were still swimming in unshed tears. He squeezed her hand gently, trying to offer her both his gratitude and, somewhat to his surprise, some reassurance. There was not another female in the world, to whom he was not related, who could testify that Lord Deben had shown the slightest hint of concern for her welfare.

But no man, not even one as immune to fellow feeling as people often accused him of being, could fail to be moved by her plight. She had come out here to indulge in a private fit of tears, only to find herself obliged to have her breakdown exposed, and, to crown it all, to have not only her own character, but that of her chaperon quite unjustly ripped to shreds.

‘She is wearing a purple turban,’ she hissed in an undertone, ‘with one white and one purple ostrich feather in it. You really cannot miss it.’ And then, snatching her hand from his, she said, ‘I think it would be for the best if I wait out here.’

‘Yes, indeed,’ put in Miss Waverley in a sugary-sweet voice. ‘You would not want to walk across that ballroom, not as you are. You really need to give your face a good wash before you let anyone see you.’

Miss Gibson hastily swiped at her cheeks with the backs of her hands. The effect, since her gloves were as badly soiled as her gown, was unfortunate.

‘Allow me,’ he said, producing a square of monogrammed white silk from his tailcoat pocket with a flourish and offering it to her.

‘Thank you, sir,’ she said gruffly and proceeded to take it from him with such reluctance that he suspected she would have refused it altogether were she not so desperate.

Why was that? he wondered. If she had taken a dislike to him, as seemed to be the case from the way she glared at him, after blowing her nose with a very unladylike thoroughness, then why had she come to his aid in the first place?

Or perhaps, as she had stated, it was just that she did not like to have any gentleman see her in such an unbecoming state of distress.

That must be it.

He turned, satisfied that he had accounted for the unwarranted hostility he could detect in her attitude, and made his way along the terrace, back to the ballroom.

Now all he had to do was find a woman of advancing years, in an ostrich-feathered purple turban, pass on the information that Miss Gibson was outside awaiting her assistance and he could lay the whole matter to rest.

Although he could not quite shake off an unfamiliar feeling of wishing he could do something to alleviate Miss Gibson’s distress. He’d realised, in the instant the threat of becoming leg-shackled to a creature of Miss Waverley’s calibre loomed before him, that he would rather die than face a marriage such as the one endured by his own father. And he was becoming more and more convinced that Miss Gibson had intervened to save him from just such a fate.

That must be it. She could not bear to see anyone forced into a marriage that was not of their own choosing.

Perhaps that was why she was out here crying. From what Lady Chigwell had said, she was not from a very good family. Perhaps she was being coerced to marry ‘well’ in order to advance their social standing. Perhaps that was what she was doing here tonight. Being put on display, to be sold off like a slave at auction. He had not seen her at her best just now, but her very youth, her very vulnerability, would hold enough appeal to interest several men he knew who were casting about them for wives this Season. It was the way of the world. Older men with money and status could more or less have their pick of the young virgins who came up to town each year to find a husband. The families of said virgins practically sold them off to the highest bidder, no matter what their feelings.

Denied choice in the matter, they eventually rebelled and took lovers of their own choosing.

Having freedom of choice was the one benefit that, as a man, he had which many women were not permitted. And he’d almost thrown it away.

It had been Miss Waverley who had shocked him out of the apathy that had almost led him to make a disastrous error. He held such cynical views of marriage that he’d been on the verge of allowing fate to take the choice out of his hands. Like a gambler, who tossed a coin to determine his next move. He’d thought it would simplify things to remove the element of choice from the equation. No such thing. Marriage, once entered into, was an inescapable bond. Reluctance to enter that state did not excuse a cavalier attitude towards the choice of bride. Though he still could not imagine finding any real pleasure for himself, in marriage, he owed it to his children to thoroughly investigate the character of the woman who would bear them. He would never knowingly foist a parent like his own mother upon poor innocent children. Nor a woman like Miss Waverley.

She might have jolted him out of his fatalistic attitude this evening, but it was only because she epitomised all he most despised in females.

He felt no gratitude towards her whatsoever. And yet, in spite of her intervention being quite unnecessary, the fact that Miss Gibson seemed to have acted out of concern for him did make him feel as though he wished he could repay her in some way.

For nobody, male or female, had ever attempted to rescue him from anything.

Good God. He stood stock still, smiling with unholy mirth at the thought that suddenly struck him. He’d just been rescued by a damsel in distress.

Not that anyone could, by any stretch of the imagination, think of him as a knight in any kind of armour. He fought his battles in the House of Lords, with cutting words rather than at tourneys, with lance and mace.

He turned, he was not entirely sure why, to take one last look at her—and caught Miss Waverley shooting her a look of pure venom.

He’d already ascertained that she was amoral and ruthless. And though Miss Gibson clearly possessed a great deal of courage, she appeared to be socially inferior to the scheming Isabella. Which rendered her vulnerable to the kind of attack he had no doubt the girl would launch at the first available opportunity.

He had wondered how he might repay Miss Gibson for helping him preserve his liberty. Now he knew. Over the next few weeks, at the very least, he would keep a discreet watch over her.

Or heaven alone knew what twisted form of revenge the thwarted Miss Waverley would exact.

Chapter Two

Another day in London.

Henrietta looked out of the drawing-room window at the row of houses across the street from the one her Aunt Ledbetter inhabited, repressing a sigh.

Too many buildings squashed together, too many people thronging the narrow streets, too much noise and bustle, and an overpowering concentration of smells. She had only been here just over a month and already she longed for the peace and quiet of Much Wakering: the wide skies, the sound of birdsong and the scent of blossom.

From her bedroom window she could see just one tree, if she hung out over the windowsill and craned her neck. One miserable, stunted sapling that looked as out of place in its environment as she felt.

‘What did you think of the performance, Miss Gibson?’

Henrietta started and pulled her attention back to her aunt’s guests. Or at least, the one guest who was trying to include her in a conversation to which she had not been giving her full attention. She had hoped that going to sit on a chair on the fringes of the room would have been enough to deter people from obliging her to talk. But Mrs Crimmer was not an easy person to deter from any course upon which she set her mind.

‘The performance? Oh, I, um …’ They had gone to the theatre the night before. In truth, if she were in a better frame of mind, she would have enjoyed the spectacle. But ever since Miss Twining’s ball there had been a cold lump of misery lodged just beneath her breastbone, which not even the most skilled of clowns could alleviate, and a fog of depression hanging round her through which everything she saw seemed grey and unappealing.

As unappealing as she knew herself to be.

The only thing that managed to make her haul herself out of bed in the mornings was the knowledge that if she lay there all day feeling sorry for herself, her aunt would worry. Mrs Ledbetter had done so much more than just accept the responsibility when her father had written to his cousin to ask if she might supervise a Season in London. Mrs Ledbetter had flung herself into the task with an enthusiasm which had taken Henrietta by surprise. At first, she’d been inclined to feel a bit offended by the way ‘Aunt’ Ledbetter had shaken her head and clucked her tongue as she’d watched the maid unpack her clothes. But then she’d never had a female relative supervise her wardrobe, at least not since her mother’s death so many years ago. And any offence soon melted away under the discovery that Mrs Ledbetter did not just enjoy shopping for clothes, but derived enormous pleasure from discovering which colours or styles became her the most. When she wasn’t taking her shopping for garments and all sorts of accessories Henrietta had no idea were absolutely essential, she had hired people to round her off in other ways. A friseur had come to the house to cut and style her hair. A dancing master visited regularly to teach her the steps of all the dances she had always wished she might be able to do, but had never had the opportunity to learn.

And her kindness continued, day after day. She organised trips to the theatre or the latest exhibitions, and took her to musical evenings and dinner parties where she introduced her to all her friends and acquaintances. Nothing was too much trouble. And, considering her own daughter Mildred was at an age to be considering matrimonial prospects herself, she might easily have treated Henrietta as a rival, or a threat, or even just an imposition.

Neither mother nor daughter had done any such thing. They had welcomed her into their circle with open arms.

For their sakes, Henrietta drew on all her reserves of will-power and mustered up a wan smile.

‘We have nothing like it in Much Wakering, Mrs Crimmer,’ she said quite truthfully. ‘So many talented acts, one after another. It was quite, um …’

‘Overwhelming, was it, my dear?’

Mrs Crimmer, the wife of one of Mr Ledbetter’s business contacts, nodded her head in a sympathetic manner. People who lived in London all year round, she had swiftly discovered, tended to look upon provincials with a mixture of pity and contempt.

If Mrs Crimmer had spoken so patronisingly to her three days ago, she would have made a withering retort. Or at least, she corrected herself, she would have bitten one back, for the sake of Mildred’s prospects. For Mr and Mrs Ledbetter were hoping that Mildred would look favourably upon young Mr Crimmer’s suit.

She glanced across the room to where the red-faced young man was paying court, rather bashfully, to Mildred, while Mildred was looking decidedly unimpressed.

Her aunt and uncle, for so she had come to think of them, might have hopes in that direction, but Mildred was looking for more from life than a prosaic match to cement a business alliance. She was looking for romance.

But then Mildred was pretty enough to have romantic aspirations. She had lovely golden hair, wide green eyes and a delicate little nose that made her look like an angelic kitten.

Perhaps that was why they had all accepted Henrietta into the household so readily, she sighed. With her gawky figure and plain face, she posed no threat to her distant cousin. When the pair of them walked into a room, all masculine attention went to Mildred.

Which had not bothered Henrietta in the slightest. She did not want masculine attention. Or at least, she had only ever hankered after the attention of one man.

But even he was beyond her reach now. Three nights ago, he’d finally forced her to accept the fact that she’d been a complete fool to follow him to London. And now she could no longer even pretend to herself that, deep down, she did mean something to him.

She could never have meant anything to him, for him to treat her as he had. She reached out and took a biscuit from the plate set on the table between her and Mrs Crimmer.

She was stuck in town until the end of June, at the very earliest, for she could not bring herself to slink home. Especially not in the light of what he’d said.

You belong in the country, not in a rackety place like London, had been the opinion he’d expressed upon the only occasion he’d called upon her. I shouldn’t wonder at it if you aren’t soon aching to get back to Much Wakering.

It was galling to admit that, in a way, he was correct. She did miss the trees and the tranquillity, and the fact that everyone knew everyone else.

But that didn’t make her a country bumpkin.

It had been a shock to hear Richard—her Richard, as she’d still been thinking of him then—speak to her in such patronising tones. She had only been in town one week, after all, and of course she’d still been a bit wide-eyed and excited.

But that did not mean she would never be able to cope with the sophistication of London society. Why, Richard himself had only acquired his town bronze after several trips. At first, the difference had only been apparent in his appearance. He’d begun to look very smart in clothes bought from a London tailor. And then the way he’d had his hair cut, well, it had drawn gasps of admiration all round. That shock of unruly curls had been tamed into a style that took much of the boyish roundness from his freckled face. He’d no longer looked like the easy-going son of the local squire, but, well, just as she’d always envisioned Paris, the man so handsome goddesses had squabbled over him. But, gradually, she’d sensed an inner change, too. She’d begun to feel uneasily as if he was drawing further and further away from her. And this last Christmas there had been a veneer of sophistication about him, expressed in languid mannerisms which were so unlike those of the blunt, honest boy who had run tame in her house for years that he had made her feel positively naïve and tongue-tied.

She ought, she reflected gloomily as she snapped her biscuit in half, to have taken heed of his withdrawal then and spared herself the humiliation she’d endured at Miss Twining’s ball. Or recognised his reference to her return to Much Wakering as a hint that he didn’t want her in town. Instead, she had persuaded herself that his words were an awkward expression of concern for how she would cope. Oh, why was she so stupid? Why hadn’t she seen? If he had really been concerned about how she would cope, he would have escorted her everywhere. Haunted the Ledbetters’ house and taken steps to shield her from all the undesirable elements he warned her stalked London society.

Well, now she knew better.

She popped one half of the biscuit into her mouth, consoling herself with the fact that at least she had not confided her romantic aspirations with regard to Richard to anyone. Which meant she was the only one who knew what a stupid, pathetic fool she’d been.

Unfortunately, it also made it quite impossible to go home. If she were to start talking about leaving, everyone would want to know why she wanted to cut her stay short. And she had no plausible excuse to give. She couldn’t possibly offend her dear Aunt Ledbetter by letting her think she was in any way responsible for her present unhappiness. And she was absolutely never going to let anybody know what a fool she’d made of herself over Richard. Her heart might be bruised, but at least her pride was still intact.

And that was the rub. If she insisted on going home without confessing the full truth, they would all assume she wanted to go back to the countryside because town life was, indeed, too much for her.

Given the choice between looking like a silly girl who’d pursued a man who didn’t love her to London, or a feeble-minded ninny who couldn’t cope with being more than five miles away from her parish church, or putting a brave face on it and staying in town when all the lustre had gone from the experience, Henrietta had decided on the latter course. She would stay in town.

Besides, she owed her aunt and cousin even more since her ignominious departure from Miss Twining’s ball. They had been so gracious about it. They had fussed over her in the coach when they’d seen her tears, and expressed the kind of sympathy for the fictitious headache she’d claimed which she had never in her life experienced before. She would never have invented a headache to explain her distress if she’d known how concerned they would be. She had just assumed they would pat her hand and send her to her room for a quiet lie down, like her brothers or her father would have done.

Instead, they’d come to her room with her, with vials of lavender water to dab on her temples, and had stayed with her while she drank a soothing tisane, sharing anecdotes about their own monthly fluctuations in health until she’d been almost crushed with guilt.

Particularly as they’d both been so thrilled to get an invitation to the house of a genuine baronet—Aunt Ledbetter so that she could gossip over the details of the interior of a baronial town house with her circle of friends and Mildred because she hoped to attract the attention of one of the sons of the lower ranks of the nobility who were bound to fill the house. She had robbed them both of at least half their pleasure, just because she’d been unable to control her temper when she’d seen that cat Miss Waverley attempting to snare yet another poor unsuspecting man in her clutches.

Even when she’d tried to apologise, their response had heaped coals of fire on her head.

‘We would not have spent even that one hour in such elevated company had you not become friends with Miss Twining,’ Aunt Ledbetter had said. ‘In fact, I thought it most gracious of her to include us in your invitation at all.’

‘Yes,’ she had replied weakly. ‘Miss Twining is a lovely person.’ Which short statement had been the only truthful remark she could make about the entire affair. For she really had liked Julia Twining for the way she had not looked down her nose at Henrietta’s London connections, nor made any disparaging remarks about their background.

Unlike some people.

‘I cannot help wondering where on earth your father dredged up this set of relatives,’ Richard had said, eyeing her aunt askance on the one visit he’d paid to this very drawing room. ‘Never heard of ‘em before you took it into your head you wanted a Season. And now I’ve met ‘em, I’m not a bit surprised. Oh, not that there’s anything wrong with them, in their way. Cits often are very respectable. It’s just that they’re not the sort of people I want to mix with, while I’m in town. And if your father ever took his nose out of a book long enough to notice what’s what, he’d have known better than to send you to stay with people who can’t introduce you to anyone that matters, or take you any of the places a girl of your station ought to be seen.’

Had she really been so idiotic as to interpret that statement as an expression of concern for her? He was not in the least bit concerned for her. He was just worried that she might pop up somewhere and embarrass him with her humble relations, or perhaps her countrified ways, in front of his newer, smarter, London friends.

But, she consoled herself, stuffing the other half of the biscuit into her mouth, at least she’d had the spirit to object to the disparaging way he’d spoken about her father.

‘Papa cannot help being a bit unaware of what London society is like,’ she had said, firmly. ‘You know he hardly ever comes up to town any more, and when he does it is only because he has heard that some rare book has finally come on the market.’ After all, she could not deny that Richard’s accusation was, in part, justified. She had not been a week in town before realising that because his cousin had married a man of business, she did not have, as Richard had so scornfully pointed out, the entrée into anywhere even remotely fashionable. ‘And anyway,’ she’d continued, loathe to admit to her disappointment, ‘if he did know, he would probably think it highly frivolous. He never judges a man by his rank or wealth, as you should know by now. How many times have you heard him say that a man’s real worth stems from his character and his intellect?’

She reached for another biscuit, feeling rather pleased with herself for taking that stance, even when she had still been Richard’s dupe. But then nothing would make her tolerate any criticism of her father, from whatever quarter it came.

Besides, he already felt badly enough about the discovery that she had somehow attained the age of two and twenty without him having done anything about finding her a husband.

The slightly bewildered look had crossed his face—the one he always adopted when forced to confront anything to do with the domestic side of life—when she had first tentatively broached the subject of having a London Season. ‘Are you quite sure you are old enough to want to think of getting married?’ He had then taken off his spectacles, and laid them on his desk with a resolute air. ‘But of course, my dear, if you want a Season, then you must have one. Leave it with me.’

‘You … you won’t forget?’ It would have been just like him. And he knew it, too, for instead of reprimanding her for speaking in such a forthright manner, he had smiled and assured her that, no, when it came to something as important as his only daughter’s future, he most certainly would not forget.

And he hadn’t forgotten. He just hadn’t got it quite right. But since she had not the heart to disillusion him about the wonderful time he hoped she was having, she had kept her letters home both cheerful and suitably vague.

Mrs Crimmer was still chattering away, but Henrietta had not heard a word for several minutes while she had been alternately woolgathering and munching her way methodically through the entire plate of biscuits. Her mind had not been able to do much more than go over and over the night of Miss Twining’s ball for days. It had all been so very much more painful, she had decided, because she’d pinned such hopes on it. And on Miss Twining herself. She really had hoped they might be friends. It hadn’t seemed to matter to her that she was staying with unfashionable relatives in the least. Miss Twining had even said she might call her Julia, she sighed, reaching for the last biscuit.

But the incident at the ball had destroyed any possibility that friendship could blossom between them, even if they’d had anything in common, which there hadn’t been time to find out, for she had left the ball before Miss Waverley, so that it would be Miss Waverley’s version of events that everyone would hear. And she knew such a schemer would not waste the heaven-sent opportunity to blacken her enemy’s reputation.

Not that she cared. She had no wish to step outside her aunt’s social circle ever again.

What was the point?

‘I say, what a bang-up rig,’ remarked Mr Bentley, who was lounging against the frame of the other window, amusing himself by watching the passing traffic. He was a friend of Mr Crimmer junior. She rather thought his role today was not only to provide moral support during the gruelling ordeal of attempting to make Mildred smile on him, but also to bear him company to the nearest hostelry, once they had stayed the requisite half-hour, to help revive Mr Crimmer’s battered spirits.

‘Pulled up right outside, as though he means to pay a visit here. By Jove, he does, too. He’s coming up the steps.’

On receipt of that information her aunt, to everyone’s astonishment, leapt from the sofa upon which she had been sitting and reached the window in one bound.

‘Oh, my goodness,’ she exclaimed, having thrust Mr Bentley aside and peered out. ‘He said he would call, but I never dreamed for one moment that he meant it. Even though he asked so particularly for our direction.’

Henrietta froze, the last biscuit halfway to her mouth. From her vantage point she, too, had seen the stylish curricle pull up in front of the house and had already recognised its driver.

‘Henrietta, my dear,’ said Aunt Ledbetter, whirling round to face her, ‘perhaps I should have mentioned it before, but …’ She paused at the sound of the front door knocker rapping. ‘Lord Deben said he might call, to see how you were, after …’ She checked, as though only just recalling that her drawing room was full of visitors. ‘After you were taken ill at Miss Twining’s ball.’

Voices in the hall alerted them to the fact that Lord Deben had entered the house.

Aunt Ledbetter sprinted back to her sofa and sat down hastily, arranging her skirts and adopting a languid pose, as though she had earls dropping in upon her every day of the week.

All conversation ceased. Every eye turned towards the door.

‘Lord Deben,’ announced Warnes, their butler.

Lord Deben strode into the room and paused, looking about him down his thin, aristocratic nose.

Henrietta’s hackles rose. He’d walked into Miss Twining’s house wearing just the same expression, as though he couldn’t quite believe he’d graced the place with his presence. Back then, she hadn’t known who or what he was, but the impression he had made on the others, his knowledge of it and his contemptuous reaction, had given her an instant dislike of the man.

His gaze swept her aunt’s drawing room with an air that somehow conveyed the impression he did not see anyone until his eyes came to rest on her.

‘Miss Gibson,’ he said, crossing the room to where she sat, ‘I trust I find you in better health today?’

It was all Henrietta could do to bite back an enquiry as to whether he had ever had any manners, or whether he just did not see the need to employ them today. What kind of man ignored his hostess, let alone the other occupants of the room?

But then Richard had behaved just like this when he’d come here, too. Richard had thought himself too good for this company. Richard had not deigned to speak to any of them either, dismissively referring to them as a bunch of clerks and shopkeepers. Though even he had, in deference to good manners, at least given Aunt Ledbetter a perfunctory bow before giving his undivided attention to Henrietta.

So she was not in the least bit flattered by the way Lord Deben bowed over her hand. When it looked as though he meant to kiss it, she raised it to her own mouth instead, shoving the last of the biscuits defiantly between her teeth.

She heard Mildred gasp.

Lord Deben’s expression did not alter one whit.

‘You still look a trifle peaked,’ he informed her, shutting out the other occupants of the room by the simple pretext of standing with his back to them all. ‘I shall take you out for a drive in the park. That should put the bloom back in your cheeks.’

‘You will take me out for a drive,’ she repeated. What unmitigated gall! Did he think she was so stupid she couldn’t see how he was snubbing her poor dear aunt? Besides, what if she didn’t want to go out? What then? She was just about to inform him that nothing on earth would induce her to leave this room, in the company of a man who clearly thought he was too good for it, when Mr Bentley burst out,

‘My word, what I wouldn’t give for a chance to tool that set-up round the park. Or even sit up beside you, my lord.’ He shot Henrietta a look loaded with envy. ‘You lucky, lucky girl!’

Lord Deben’s heavy lids lowered a fraction. He turned towards Mr Bentley, his lip curling. ‘I do not generally invite young gentlemen to escort me in the park during the fashionable hour,’ he remarked in a crushing tone that instantly reduced his admirer to red-faced silence.

He hadn’t invited her, either. Issued an order, more like.

‘And it is very generous of you to invite Henrietta,’ said her aunt, shooting her a look loaded with meaning. ‘Such an unlooked-for honour. It will not take her but a moment to run upstairs and put on a bonnet and coat.’ She made shooing motions towards Henrietta behind Lord Deben’s back. ‘Will it, my dear?’

No, it wouldn’t. And it would be better, much better for her aunt if she got him out of the house to tell him what she thought of his manners, than create a scene in her aunt’s drawing room.

‘Make haste,’ he said to Henrietta brusquely, finally succeeding in grasping her hand and using the hold he gained upon it to lift her to her feet. ‘I do not want to keep my horses standing.’

His horses! Well, that put her in her place. He rated their welfare far higher than such a paltry consideration as her sensibilities!

Who did he think he was? To come in here and comprehensively insult everyone like that?

Henrietta swept out of the room on a surge of indignation that completely banished the lethargy that had made even walking require a huge effort of will-power since Miss Twining’s ball.

Not keep his horses waiting, indeed! She marched up the stairs and flung open the door to her room.

And to crush poor Mr Bentley, she fumed as she strode across to the armoire and yanked it open, who’d only been expressing the kind of boyish enthusiasm for the splendour of his horses that any of her brothers might have done.

And to ignore her aunt and her cousins like that! Just because they were connected to trade! Because he thought they were common.

Well, she’d show him common.

She stuffed her arms into the sleeves of her mulberry redingote, then marched along the corridor to her aunt’s room, where she ruthlessly plundered her selection of furs until she found the fox. She slung it round her shoulders, pausing before the mirror only long enough to assure herself that it did indeed clash with her coat as horribly as she’d hoped, before making for Mildred’s room and the high-crowned bonnet, topped with a pair of bright red ostrich feathers, which had only arrived the morning before.

When she reappeared in the drawing room, not five minutes after she’d left it, Mildred’s jaw dropped. Her aunt made a faint choking noise.

Lord Deben, who was standing at the window, next to Mr Bentley, cocked his head to one side as his lazy brown eyes scanned her outfit.

‘More colour already,’ he drawled with a perfectly straight face, ‘just at the mere prospect of taking the air.’

‘Oh, yes,’ she agreed with a smile as she stalked towards him. ‘I am so looking forward to being seen driving round the park with you, at the fashionable hour.’

This would serve him right! He looked just the type of man who would hate being seen driving about with someone who looked positively vulgar. He might have lowered himself by inviting a girl to drive with him who was well outside the circles in which he normally moved, but he had taken the greatest care over his own outfit. She knew enough about male fashion to guess that his clothing hailed from the most expensive, exclusive tailors. And he had shaved, very recently. His cheeks had that sheen that only lasted an hour or so after the event, and besides, when he had bent over her hand to attempt to kiss it, she had smelled oil of bergamot.

‘How little did I think,’ she simpered, ‘when I came up to town that I should have the honour of being taken driving by such an important man. In such a … a bang-up rig, too.’

His face, she noted with savage pleasure, was growing more wooden by the second.

‘I shall be sure to give you a full account of my treat, Mr Bentley—’ she beamed at the youth whose eyes were swivelling from the immaculately clad earl, to the ostrich feathers adorning her borrowed hat with something like horror ‘—next time you call upon us.’

Lord Deben gestured for her to precede him into the hall and, with her ostrich plumes bobbing in time to her martial stride, they set off.

Chapter Three

So what if he had finally found some semblance of manners and opened the door for her? It meant nothing. Except, perhaps, that he couldn’t wait to escape the presence of people he considered so far beneath him.

So what if he was a good driver? Just because he could weave in and out of the heavy traffic with an ease of manner that made it look effortless, when she knew it required great skill, did not make him any less unlikeable.

She was almost glad when, having swept through the park gates, he repeatedly cut people dead who were trying to attract his attention. It made it so much easier to cling to her bad humour, which the thrillingly rapid drive through the teeming streets had almost dispelled.

‘You are not an easy person to run to ground,’ he said suddenly, just when she was beginning to wonder whether the entire outing was going to take place in silence. ‘I looked for you at the Cardingtons’ and the Lensboroughs’ on Tuesday, the Swaffhams’, Pendleboroughs’, and Bonhams’ last night. And I regret to say that I do not have much time to spare on you today, even though it is imperative that we have some private conversation regarding what happened at that débutante’s ball whose name escapes me for the moment. Hence the abduction.’ He turned and bestowed a lazy smile upon her.

She felt a funny jolt in her stomach. There was something in that look that almost compelled her to smile back. Which was absurd, since she was very cross with him.

Reminding herself that he could not even recall the name of the girl she’d hoped might have become a friend was just what she needed to bolster her resentment.

‘On Tuesday night,’ she therefore retorted, ‘I was at a dance held by the Mountjoys. They are vintners. I don’t suppose you know them. And last night we went to the theatre in a party with most of the people who were sitting around the drawing room just now.’

‘Mountjoy …’ he mused. ‘I think I do know of them. I have a feeling they supply my cellars at Deben House.’

‘I shouldn’t be a bit surprised. They boast of having the patronage of several of the more well-heeled members of the ton, though not the entrée into their homes.’

‘Ah,’ he said.

‘And before you ask how I came to be at such an exalted affair as Miss Twining’s come-out ball, it was entirely due to the offices of my brother Hubert, who serves in the same regiment as her brother Charlie. Charlie wrote to her, asking if she wouldn’t mind calling on me, because I wasn’t likely to know anyone in town just at first.’

Not that he’d thought of it as an exalted affair. To judge from the look on his face, he’d regarded attendance as a tedious duty, probably undertaken out of some kind of obligation to the elderly lady he’d been escorting.

While for her it had been an evening that should have brought nothing but delight.

Well, neither of them had got quite what they’d expected.

At the time he’d walked in looking all cynical and bored, she’d still been full of hope she might run into Richard there. Miss Twining was bound to have sent him an invitation, since he, too, was friendly with her brother Charlie. And she was fairly sure that he would have called in for half an hour, at least, to ‘do the pretty’, even if he did not stay to dance. She had so hoped that, seeing her all dressed up in her London finery, with her hair so stylishly cut, her brother Hubert’s best friend would at long last see that she had grown up. See her as a woman, to be taken seriously, and not just one of his childhood playmates that he could casually brush aside.

‘Had I known how you are circumstanced,’ said Lord Deben, interrupting her gloomy reflections of that fateful night, ‘I would have called upon you sooner.’

‘But you did know how I am circumstanced. Lady Chigwell took great pains to let you know that she considered I was intruding amongst my betters.’

‘I assumed that was spite talking and discounted it. Particularly when I looked you up and discovered that you have a much more impressive pedigree than Lady Chigwell, whose husband’s title, such as it is, is a mere two generations old.’

‘You looked me up …?’

‘Of course. I had no intention of asking around and raising people’s curiosity about why I wished to know more about you. When I found that you are Miss Gibson of Shoebury Manor in Much Wakering and that your father is Sir Henry Gibson, scientist and scholar, member of the Royal Society, I naturally assumed you would be attending the kind of events most débutantes of your age enjoy when they come up to town for their Season.’ His mouth twisted with distaste. ‘Had I known that you would not, no power on earth would have compelled me to attend any of them.’

He’d spent two consecutive evenings haunting places he did not want to go to, merely because he had thought she might be there? And now she was obliging him to drive round the park, at the fashionable hour, while she was dressed in such spectacularly vulgar style?

For the first time in days, she felt almost cheerful.

‘What a lot of time you have wasted on my account,’ she said, with a satisfied gleam in her eye.

‘Well, it is not because I have been struck by a coup de foudre,’ he said sharply. ‘Do not take it into your head that I have an interest in you for any sentimental or … romantic reason,’ he said with a curl to his lip as he glanced at her out of the corner of his eye.

‘I wouldn’t!’ The coxcomb! Did he really believe that every female in London sighed after him, just because Miss Waverley had flung herself at him?

‘Let me tell you that I wouldn’t want to attract that kind of attention from a man as unpleasant and rude as you,’ she retorted hotly. ‘In fact, I didn’t want to come out for a drive with you today at all. And I wouldn’t have, either, if it wouldn’t have meant embarrassing my aunt.’

His full lips tightened in displeasure. Nobody spoke to him like that. Nobody.

‘It is as well I gave you little choice, then, is it not?’

‘I do not see that at all. I do not see that there is any reason for you to have looked for me, or investigated my background, or dragged me out of the house today …’

‘When you were clearly enjoying the company so much,’ he sneered.

She blinked. Had her misery been that obvious?

‘It was nothing to do with the company. They are all perfectly lovely people, who have very generously opened their home to me …’

He frowned. He had dismissed the suspicion that she had taken him in aversion on that accursed terrace, assuming she was just angry at the whole world, because of some injustice being perpetrated upon her. But he could not hold on to that assumption any longer. From his preliminary investigation into her background, and that of her father, and the people with whom she was living, he could find no reason why anyone should attempt to coerce her into marriage. He had not yet managed to find out why she was living with a set of cits in Bloomsbury, when she had perfectly respectable relations who could have presented her at court, but she clearly felt no ill will towards them for not being able to launch her into society. She had just referred to them as perfectly lovely people, putting such stress on the pronoun that he could not mistake her implication that she excluded him from the set of people she liked.

In short, his first impression had been correct. She really did not like him at all. His scowl landed at random upon the driver of a very showy high-perch phaeton going in the opposite direction, causing the young man such consternation he very nearly ran his team off the road.

‘Then I can only deduce that whatever is still making you look as though you are on the verge of going into a decline had its origins at Miss Twining’s ball.’

His scowl intensified. He was inured to enduring this level of antagonism from his siblings, but he had no experience of prolonging an interaction with a person to whom he was not bound by ties of family who held him in dislike. It was problematical. He was not going to rescind his decision to provide a bulwark against whatever malice Miss Waverley chose to unleash upon her, but he had taken it for granted she would have received his offer of assistance with becoming gratitude. After all, he was about to bestow a singular honour upon her. Never, in his entire life, had he gone to so much trouble on another person’s behalf.

The usual pattern was for people to seek him out. If they didn’t bore him too dreadfully, he generally permitted them limited access to his circle, while he waited to discover what their motives were for attempting to get near him.

He turned his glare sideways, where she sat with that beak of a nose in the air, completely shutting him out.

The corners of his mouth turned down, as he bit back a string of oaths. What the devil had got into him? He did not want her to fawn over him, did he? He despised toadeaters.

It must just be that he was not used to having to expend any effort in getting people to like him. He didn’t quite know how to go about it—

Hold hard—like him? Why the devil should he be concerned whether this aggravating chit liked him or not? He had never cared one whit for another’s opinion. And he would not, most definitely not, care about hers either.

Which resolve lasted until the moment she turned her face up to his, and said, with a tremor in her voice, and stress creasing her brow, ‘I don’t, do I? Please tell me I don’t look as though I’m going into a decline.’

‘Well, Miss Gibson—’

‘Because I am not going to.’ She straightened up, as though she was exerting her entire will to pull herself together. ‘Absolutely not. Only a spineless ninny would—’ She shut her mouth with a snap, as though feeling she had said too much.

Leaving him wishing he could pull up the carriage and put his arms round her. Just to comfort her. She was struggling so valiantly to conceal some form of heartbreak that his own concerns no longer seemed to matter so very much.

Of course, he would do no such thing. For one thing, he was the very last person qualified to offer comfort to a heartbroken woman. He was more usually the one accused of doing the breaking. And the only comfort he’d ever given a female had been of the hot and sweaty variety. With his reputation, and given what he knew of her, if he did attempt to put his arms round her Miss Gibson would no doubt misinterpret his motives and slap his face.

‘This is getting tiresome,’ he said. ‘I wish you would stop pretending you have no idea why I sought you out.’

‘I do not know why you should have done such a thing. I never expected to see you again, after I left that horrid ball. Especially not when I found out that you are an earl.’

‘Two earls, if you count the Irish title. Not that many people do.’

‘I don’t care how many earls you are, or what country you have the authority to lord it over, I just wish you had left me alone!’

‘Tut tut, Miss Gibson. Can you really believe that I would not wish to take the very first opportunity that offered to thank you for coming so gallantly to my rescue?’

‘To thank me?’ He had gone to all this trouble to express his thanks?

He watched her subside on to the seat, her anger visibly draining away.

‘Oh, well …’

‘Miss Gibson, I do thank you. From the bottom of what passes for my heart. It is not an exaggeration to say you saved me from a fate worse than death.’

‘Having to get married, you mean?’

‘Oh, no, never that. Had you not intervened, I would merely have repudiated Miss Waverley, stood back and watched her commit social suicide by attempting to manipulate me,’ he corrected her. ‘Absolutely nothing would have induced me to tamely fall in with her schemes. I would rather take a pistol and shoot myself in the leg.’

‘Oh.’ To say she was shocked was putting it mildly. She had grown up believing that gentlemen adhered to a certain code of morals. But he had just admitted he would have allowed Miss Waverley to ruin herself, without lifting so much as a finger to prevent it.

‘Oh? Is that all you have to say?’ He had just, for some reason, confided something to her that he would never have dreamed of telling another living soul. Though for the life of him he could not think why. And all she could say was Oh.

‘No. I … I think I can see now why you wished to speak to me privately. That … kind of thing is not the … kind of thing one can talk about in a crowded drawing room.’

‘Precisely.’ He didn’t think he’d ever had to work so hard to wring such a small concession from anyone. ‘Hence the ruthless abduction.’ Well, he wasn’t going to admit that a large part of why he’d detached her from her family was because he still harboured a suspicion there could be some sinister reason for her having been sent to them. It would make it sound as though he read Gothic novels, in which helpless young women were imprisoned and tyrannised by ruthless step-parents, and needed a daring, heroic man, usually a peer of the realm, to uncover the foul plot and set them free.

‘I had hoped to find you at the kind of event where I could have drawn you aside discreetly and thanked you before now.’

‘Oh.’ She wished she could think of something more intelligent to say, but really, what was there to say? She had never met anyone so utterly ruthless. So selfish.

Except perhaps Miss Waverley herself.

‘I regret the necessity of being rather short with your estimable relation and her guests, but I am supposed to be working on a speech this afternoon.’

‘A speech?’

‘Yes. For the House. There is quite an important debate currently in progress, on which I have most decided views. My secretary knows them, of course, but if I once allowed him to put words into my mouth, he might gain the impression that I was willing to let him influence my opinions, too. Which would not do.’

He frowned. Why was he explaining himself to her? He never bothered explaining himself to anyone. Why start now, just because she was giving him that measuring look?

On receipt of that frown, Henrietta shrank in shame. Her aunt had positively gushed about what an important man Lord Deben was, and how people had stared to see him being so gracious to them when Henrietta was ‘taken ill’, and the more she’d gone on, the more Henrietta had resented him. She’d thought he was just high and mighty, looking down his nose at them because he had wealth and a title. But now she realised that he really was an important, and probably very influential, man. And he was telling her that he took his responsibilities quite seriously.

She could not wonder at it that he looked a little irritated to be driving such a graceless female around the park when he ought to be concentrating on matters of state.

And she supposed she really should be grateful for the way he was handling his need to thank her. She most certainly did not want to risk anyone overhearing anything that pertained to the events that had occurred on the terrace either.

Nor the ones that had propelled her out there.

‘I apologise if I have misconstrued your, um, behaviour,’ she said. ‘But you need not have given it another thought. And I still don’t see why …’

‘If you would just keep your tongue between your teeth for five seconds, I might have a chance of explaining.’

There was a tightness about his lips that spoke of temper being firmly reined in. A few minutes ago, she would have been glad to see that she was nettling him.

But not now, for she was beginning to suspect she might have misjudged him. And deliberately chalked up a list of crimes to his account, of which, if she were honest with herself, it was Richard who was guilty.

It had started when he’d come out on to the terrace just when she’d most needed to be alone. As she’d dived behind the planters, she’d banged her knee and roundly cursed him. And then, recalling the look he’d had on his face when he’d arrived at the ball, she’d promptly decided he was exactly like Richard. From then on, resentment had steadily built up, when to be truthful, she really did not know anything about this man’s character at all.

It was about time she gave him a chance to explain himself. So she made a show of closing her mouth and turned her face to look up at him, wide-eyed and attentive.

A slight relaxation about his mouth showed her that he had taken note of her literal obedience.

‘You made an enemy of Miss Waverley that night,’ he said. ‘And since you came to my defence, I felt I owed it to you to warn you. If she can find any way to do you harm, be assured, she will do it.’

‘Oh, is that all?’ Henrietta relaxed and leaned back against the back of the bench seat.