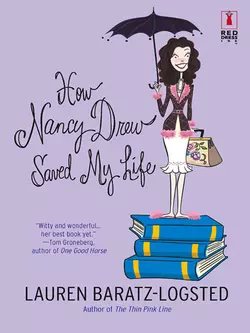

How Nancy Drew Saved My Life

Lauren Baratz-Logsted

Broken, smashed and stomped in the mudThat's how Charlotte Bell's heart ended up the last time she let her emotions heat up on a nanny assignment. So taking a new position in frigid Iceland, working for Ambassador Edgar Rawlings, might be just what Charlotte needs in order to heal up—and chill out. This time, she's determined to be intrepid and courageous. She's even read all fifty-six original Nancy Drew books in preparation. Unfortunately, she's neglected to find out anything about Iceland or to look into the background of her oddly compelling employer. When Charlotte stumbles onto the trail of a mystery that only she can solve, she'll need every shred of Nancy's wisdom to keep her life—and her heart—safe!

How Nancy Drew

Saved My Life

Lauren Baratz-Logsted

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

For my mother, Lucille Baratz, one of the world’s greatest

ladies, and the woman who gave me my first Nancy Drew.

Mom, if I keep putting off dedicating a book to you,

will you stay with us forever?

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Epilogue

About the Author

No book is ever written in a vacuum, even if it feels that way at times, and this book is certainly no exception, so here come the curtain calls.

Thanks to Margaret O’Neill Marbury, Rebecca Soukis and the whole RDI team, with special thanks to Keyren Gerlach for going above and beyond.

Pamela Harty is in a line all by herself for restoring my faith and giving me my shot, all in one go—thank you forever.

Thanks to the Friday night writing group: Greg Logsted, Jerry Brooker, Andrea Schicke Hirsch, Rob Mayette, Lauren Catherine Simpson. What I want to know is: Who’s bringing the wine next week?

Thanks to the Monday night reading group: Irene Clarke, Anita Hannan, Cheryl McCaffrey, Jacquie Pugsley, Rebecca Tate and my longtime friend Jeannine Fagan. I’m a better reader, writer and mother because of all of you.

If I lived forever, I could not thank Sue Estabrook enough for making me a better writer and a better person.

And if I listed all the friends and family I’m grateful for we wouldn’t be here all day, but we would be here for quite a bit, so suffice it to say you know who you are and by now, you ought to know what you mean to me. That said, I would be beyond remiss not to thank those who are under my roof as I write this:

Thanks to my niece, Caroline Logsted, for bringing so much unlooked-for joy into our lives; thanks to my daughter, Jackie, who makes me marvel every day, not merely that I have a child, but that I have this child; thanks to my husband, Greg, for being the greatest man who ever lived. Without the three of you, I would be both less sane and less insane; certainly, I would be less loved.

prologue

People think it must be easy for you, when they see you out here on the wire.

They think you don’t know fear.

But what they never stop to consider is that you know fear better than anybody and your greatest fear is not being here, not taking the chance, not living this life.

Some people think it’s brave to fight in wars and I suspect it must be true. Some people think it’s brave to go after your career dream and while I wish it were personal experience talking here, I suspect that must be true, as well. But the bravest thing of all, to me, is to love another human being, to take the chance of being disappointed, to risk having your heart broken.

That’s the wire I’m talking about, the only wire that really matters in the end.

In spite of everything that happened to me, I still believe this to be true.

chapter 1

You know, none of this ever would have happened, were it not for that Maureen Dowd column in the New York Times. After all, it’s not like grown women over the age of twenty think very much about Nancy Drew, is it? Besides which, as a young girl, I’d not been much of a Nancy Drew fan. Sure, I’d seen the shelves of her books in the libraries and bookstores I frequented whenever I got the chance, but she’d seemed so other-timely, outdated, so retro in a way that would never be fashionable again.

At least that’s what I thought.

Anyway, the article had one of those oblique angles, as these things so often do, but it was generally about Iraq and the Osama bin Laden Presidential Daily Briefings. The tie-in with Nancy Drew was that we really needed someone brash and intrepid like her involved, and questioned where all the brash and intrepid people had gone.

As for me, at the age of twenty-three, I no longer felt brash and intrepid, since events had conspired to rob me of those feelings.

I had committed the cardinal sin of many a young woman before me, something Nancy Drew would never do: I had fallen in love with a married man—named Buster, no less; with two kids, no more. I know it was a foolish thing to do, inexcusable, too, and I know it sounds lame to say he made me fall in love with him.

Except that’s the truth.

I would have been content to admire him from afar, but he drew me in, came at me like a freight train, convinced me his wife neither loved nor understood him and they hadn’t had sex in forever—I can hear you laughing at me now!—and I was the only woman he’d ever really been in love with, that no other woman had ever been as smart or as sexy or as funny or as wonderful and nothing better had ever happened to him in his life than loving me. He convinced me it would be a crime against the universe were we not to reach for this rare chance so few people ever know in this life: to be with someone, not because both parties are settling or desperate or fooling themselves, but because all the crossed stars in the firmament had deemed it should be so.

And I fell for it.

He was like a master glassmaker, building a floor underneath me, sheet by sheet of perfect glass, laid one next to the other like the most sparking tile in the world. And he led me out to the center of that amazing floor, had me stand right in the middle waiting for my Cinderella moment. But before I got my chance to dance with the prince, the craftsmanship turned into a game of Don’t Break the Ice. You know the game, where you take turns using little red and green plastic mallets to knock the cubes of white plastic ice one by one through the red plastic frame until one poor sucker dislodges the catastrophic piece that sends the little red plastic figurine at the center thudding through to the floor. Well, it was just like that, with me playing the part of the little red plastic figurine.

Only it was so much worse.

Buster got me right where he wanted me, out on that amazingly gorgeous crystal dance floor, constructed solely for me, and then he began smashing those glass tiles he’d made for me, one by one, until at last I fell through the floor, flaying my skin, shredding my soul and breaking my heart in the process.

I had always believed there are keys to the inner workings of every person alive. When love is wrong or insufficient, people jealously guard those keys, preferring to play games instead, making the other person guess at what is required, knowing the other person will fail miserably. When love is right, good, you gladly hand over the keys; you trust, and let the other person know exactly what makes you tick, for good or ill. I gave Buster so many of my keys, I let him inside me. I thought I had his keys, too, and he just ransacked the whole fucking place, like the Grinch paying a call on Cindy Lou Who the night before Christmas, and left me with no more than some picture-hanging wire and a few nails sticking out of the walls. I should have seen it coming, but still…how could he do that to me? How could he do that to me in the way in which he did it?

I could go into all the gory details, but why bother? These stories always end the same. Suffice it to say, I was the only one destroyed, certainly not Buster.

I don’t think his wife ever knew.

I sincerely hope she did not.

Not that she was any great shakes as a human being herself.

I’ll tell you one thing for damn certain: Nancy Drew never would have fallen in love with a married man.

In the wake of my bust-up with Buster, I moved temporarily back in with my aunt Bea and her three kids. It wasn’t so much that I wanted to be there, and it was sure as rain that the four of them didn’t particularly want me back there, but I was feeling too emotionally fragile to strike out on my own right away. Plus, for one thing, my exit from Buster’s household had been too abrupt for me to find something right away—slim chance to find a decent apartment in New York City on the same day as one starts looking. Two, I didn’t intend the situation to be permanent, just long enough until I could make up my mind and clearly decide what to do next. Three, last but not least, despite that I had some savings from my long-ago glory as a commercial child star, it would dwindle with alarming speed if I took up residency for a few months—the optimum time needed, I figured, to recover from a major heartbreak—in a New York City hotel room.

Thus it was, in the wake of my breakup with Buster and having moved back in with my aunt, that I saw the Times article that led me to Nancy Drew. It was in that same edition of the Times that I found my next nannying position, for I had indeed been the nanny to Buster’s own two kids, in his Manhattan penthouse on the Upper West Side.

The classified ad read:

WANTED!

NANNY

Full-time position.

Applicants must be willing

to travel to Reykjavik.

It said the job would not start for another two months, but since there had not been any other listings in the recent weeks since I’d been checking—indeed, the recession we were supposedly not having had dried up even the nanny market—I figured it was Reykjavik or bust for me. Now, if only I knew where Reykjavik was….

It is indeed possible to be widely read, as I am, and still have black holes in one’s knowledge. So, although I’m a nanny by profession, my sense of geography sucks. I’d thought St. Louis was in the state of New Orleans—well, wouldn’t it be better if it was, both places being great for jazz, and I used to get Las Vegas and Los Angeles mixed up on a regular basis.

Don’t even get me started on where Michigan should really be.

After the part about the delayed start date, the ad listed a fax number for sending résumés.

I pulled a copy of my résumé from out of the stack in the folder on my dresser—I might not be feeling intrepid anymore, but a member of the Mary Poppins profession is always prepared—and went in search of Aunt Bea to see if she would let me use her fax machine.

Given that I’d lived in that household, a Greenwich Village town house, off and on since my father moved to Africa when I was three—more on him and my mother later—you would not think I’d still have to obtain permission for such minor things. Oh no. I’m guessing you never lived in a household like Aunt Bea’s.

I found her in her king-size brass bed—nothing about Aunt Bea’s desire for luxury was ever small—huddled under the frilly bedsheets, a can of SlimFast with a straw on the night table, the TV tuned to All My Children; another thing we differed on, to her unending horror, as I was a Days of Our Lives fan, born if not bred, just like my late mother.

Aunt Bea at fifty looked about ten years older than she needed to. Not that she didn’t make every vain effort to look younger, at least as far as clothing choices and makeup, but she’d spent so much of her life frowning that she was as in need of Botox as a shar-pei.

But she was scared of needles.

And botulism.

I had learned over time, through many trials and a whole slew of errors, that the best way to get something out of Aunt Bea was to appeal to her sense of her own needs. Certainly, appealing to her sense of my needs hadn’t gotten me anywhere.

“Excuse me?” I coughed.

“Can’t you see Erica’s about to have one of her big scenes?” Aunt Bea didn’t even look in my direction.

It seemed to me that Erica was always having big scenes and that her big scenes were never as big as Marlena’s big scenes, but what did I know?

I sucked it up and plowed on.

“There’re almost no want ads anymore in the Times,” I said woefully.

“But you have to get a job,” she said, eyes still glued to Erica. “You can’t stay here forever.”

“True, true.”

I let that rest for a minute. Then:

“In that whole big paper today, there was only one job I’m qualified for. And you know there haven’t been any other ads for nannies in weeks…”

“What job?” She looked at me sharply.

I produced the ad from behind my back, holding the résumé in reserve.

“Here,” I said. “But look, it’s all the way in Reykjavik.” I wrinkled up my nose. “Do you know where Reykjavik is?” Usually, the nose-wrinkling is an affectation on my part, but not this time. “Isn’t it in Yugoslavia somewhere—is Yugoslavia even still there?—or Poland? Cities in those countries always end in ‘k,’ right?”

“Reykjavik doesn’t ring any strong bells?” Aunt Bea asked.

I shook my head.

“Reagan?” she prompted.

“I know who he was,” I admitted cautiously.

“Gorbachev?” she prompted some more. “Big summit there? Reagan proposed complete disarmament and the Pentagon went crazy because, at that time, the USSR had a huge conventional military superiority over NATO and the West needed its nuclear deterrent? Still nothing?”

I shook my head.

“What year was this?” I asked.

“Nineteen eighty-six,” she snapped, as though only a fool, or someone like me, wouldn’t know the answer.

“It was kind of before my time,” I said. “I’m fairly certain I was still mostly preoccupied with my Little People Farmhouse back then.”

“You don’t know anything,” she said, disgusted.

I shrugged. Maybe I didn’t.

“It’s in Iceland,” Aunt Bea said.

Crap, Iceland sounded cold. Oh, well.

“Oh,” I said. “I was kind of worried you’d say that.”

“You mean you asked me when you knew all along?”

“Let’s just say I had my suspicions. I was kind of hoping for mainland Europe somewhere. So,” I said. “Iceland.”

“Population one hundred and seventy thousand in Reykjavik, last time I checked,” she said.

“Ah,” I said. “Puny.”

“Whole country doesn’t have more than three hundred thousand, I don’t think,” she said.

“You wonder why they bother,” I said.

“So,” she said, handing the paper back to me, “what are you planning to do about this? Reykjavik is nice and far away…”

There was that Aunt Bea gleam, the gleam of the aunt who loved me so well.

“Well, it does have a fax number for résumés here…”

“What are you waiting for?” Aunt Bea demanded.

Your permission, I thought, since we both know that if I had used the fax first and asked later, no matter what the good cause, even if it had been to help starving children in the Third World, you’d have done something insane like deny me hot water for a month.

Home may have been the place where, when you’re desperate, they have to let you in. But some had creepy red rooms that were like mental torture chambers in the upstairs and some homes still sucked.

“Get going!” Aunt Bea shooed me.

I went, having gotten my own way the hard way.

I may have been down and out, but I was still perky and resilient. That’s one thing you should know about me: even when I’m not feeling at all brash and intrepid, I’ve always been perky and resilient.

As I fed my résumé facedown through the fax machine, I thought about what was on the business side of it: my name, Charlotte Bell; my address, here; my early schooling, unspectacular; my two years of business college, entered into upon and completed at Aunt Bea’s insistence, since she thought I’d never amount to much and wanted to make sure I embarked on a path that would ensure this would be so. After that, of course, there was my three years in Ambassador Bertram—Buster to his friends—Keating and Mrs. Keating’s home as nanny to their two kids.

I’d gotten the Keating job through an agency. Upon receiving my business-college certificate and having decided that I didn’t want to do anything remotely business related, and having Aunt Bea at my back pushing me to get a job that would earn me enough money to get me out of the house, I’d decided to kill all the birds with one stone: I’d take a job that would, by definition, get me out of the house twenty-four hours a day.

I’d be a live-in nanny.

How hard could it be?

Perhaps I’d read too many gothic novels as a young child and was romanticizing the job, but I pictured young children looking up to me and me loving them; I pictured feeling competent.

Okay, obviously I wasn’t thinking about anything by Henry James.

The way I figured it, though, being a nanny would be the perfect confidence-building thing to get me out of Aunt Bea’s house. And, so long as nobody noticed the gaps in my knowledge, like geography, everyone involved would be better for it.

I looked again, ruefully, at the résumé I was faxing.

Since the only job I’d ever held of any substance was in the household of a man I’d made the mistake of sleeping with during most of my three-year stint there, and since being an adulteress hardly qualifies one in the eyes of the world as being good for much of anything other than more adultery, you would think I’d be trepidatious at the notion of my future riding on so little.

But if you thought that, again you would think wrong.

And isn’t it amazing how close intrepid and trepidatious are when you look at them on the page like that? Hard to believe they could be such different things and that at different points in my life I was destined to be one or the other.

One thing I was sure about: Ambassador Buster would give me the greatest reference the world had ever seen, if only to get me out of town, so that he could stop feeling so damn guilty and stop worrying that I’d turn all Fatal Attraction on him, sneaking into his house and boiling a rabbit in his pot.

In addition to football, Buster also watched a lot of movies. Really, once TiVo had entered the picture, it was a wonder he got any ambassadorial work done at all.

Nope, I was more Buster’s worry than he was mine and, really, the one thing you never want to do is piss off the nanny.

Like I said, I’m nothing if not perky and resilient, even if I’m still a far way from intrepid.

chapter 2

Fax faxed, I took myself down to my local Barnes & Noble, a three-story building I treated like a second home, attending as many author readings there as I could, haunting the stacks for new books like a crack addict searching for her next fix.

Since I had read as many literary novels and commercial truffles as I could stand for the nonce, and since Maureen Dowd had put Nancy Drew on my mind, I made my way to the children’s department and looked around until I found the originals in the series: small jacketless hardcovers, with their bright yellow spines and blue lettering, the original old-fashioned artwork still on the front.

Feeling pluckier already, I plucked the first one off the shelf. It was The Secret of the Old Clock. I turned it over, expecting there to be some description of the plot of the book, but all there was was some kind of all-purpose blurb about the series—“For cliff-hanging suspense and thrilling action…”—and a listing of the first six titles in the series, followed by the promise, “50 additional titles in hardcover. See complete listing inside.”

Fifty-six seemed like an awful lot of titles to have to live up to “cliff-hanging suspense” and “thrilling action,” particularly if they featured the same character time and time again. How good could Nancy Drew be? Was she really that exciting or was someone pulling the young consumer’s leg?

As I’d said before, I’d never read much Nancy Drew as a young girl, could only remember liking The Witch Tree Symbol, better known to whoever compiled that comprehensive list at the back of the book as #33.

I plucked #33 from the shelf, flipped through it, the memories flooding me. There was Nancy climbing on top of a tabletop, holding a lantern up to a ventilator and passing one hand in front of the light at intervals such that the S.O.S. signal would be transmitted, over and over again. (I’d have just screamed for help and then died before anybody came, because help was too far away to hear a scream but it could see a well-planned S.O.S. signal.) There was the young detective, at the end of the book, not thinking about what she’d just been through but rather turning her mind to the next mystery, with a ham-fisted authorial plug for The Hidden Window Mystery, #34.

I put the book back on the shelf. It all seemed so…kitschy.

But suddenly I found myself curious, curious to know what had attracted generations of readers. Even if I had always assumed her to be too retro for my tastes, year after year the books had kept selling. And, surely, if Maureen Dowd was touting her as the answer to the world’s problems…

It took several scoopings, but I scooped up all fifty-six books, everything from #1, The Secret of the Old Clock—and that clock on the cover really did look old, with Nancy sitting there on the ground at night, looking all intrepid in her green dress and sensible watch, legs tucked ladylike to the side as she prepared to do something unladylike to that clock with the handy screwdriver in her hand—to #56, The Thirteenth Pearl, with its vaguely pagodaish cover. So #56 was the last one? I thought. God, I hoped she didn’t die in the end. Even if I didn’t end up liking her any more than I had as a little girl, that’d just kill me after reading about her for fifty-six books. I was fairly sure that after reading all fifty-six books, I’d start feeling attached.

Then I noticed that there were other books on the shelves with “Nancy Drew” on their spines but with different packaging. So she did live on!

I hauled my armloads over to the nearest available register and plunked the books down.

“A completist’s present for some special young person?” the young man at the counter asked.

“Yes,” I said, opening my wallet to pull out the necessary cash. “Me.”

He raised a tastefully pierced eyebrow.

“My childhood wasn’t so good and adulthood hasn’t been much better so far,” I said, “so I’m doing a do-over here.”

He just shrugged. Apparently, he’d waited on weirder.

Fifty-six books at $5.99 each came to…

“Three hundred and thirty-five dollars and forty-four cents plus tax,” he said. “Cash or cre—?”

I handed over the cash.

Okay, so maybe I was an out-of-work and underpaid nanny looking to become an in-work and underpaid nanny yet again, but I did have cash left over from my commercial child-star days.

So then why, you may well ask, was I living off of Aunt Bea’s meager largesse when I could have afforded a place of my own?

Because when Buster had broken my stupid little heart, he’d shattered it completely, despite the justified anger I tried to cling to. I’d been absolutely shattered, having believed I’d found true love, only to have it smashed away—and the only place I’d had the strength to go to was home, such as it was; home to Aunt Bea.

Nancy and I have nothing in common, I thought, absolutely nothing, as I read the beginning of #1.

It said that Nancy Drew was an attractive girl of eighteen, that she was driving along a country road in her new, dark blue convertible and that she had just delivered some legal papers for her father.

Apparently, her dad had given her the car as a birthday present and she thought it was fun helping him in his work.

It went on to say that her father was Carson Drew, a well-known lawyer in River Heights, and that he frequently discussed puzzling aspects of cases with his blond blue-eyed daughter. Smug, I thought, Nancy was pleased her father relied on her intuition.

Nancy was nothing like me. She was five years younger, for one thing. She also drove, a convertible no less; I couldn’t even drive a donkey cart, had never even bothered getting my license. Who needed a car if you’d lived all your life in the city? It would only be a nuisance here, even a convertible in the summer. Besides, I was kind of terrified of driving, would rather poke a needle through my own eye than be responsible for powering a vehicle.

Nancy also had a father who trusted her to help him with things, while all I had was Aunt Bea to trust that I would fuck everything up and a father in Africa whom I rarely saw. I seemed to remember Nancy being motherless, like me, but somehow I doubted we’d lost our mothers in the same fashion.

Finally, there was that whole thing about her being blond and blue-eyed—wasn’t she supposed to be famously titian-haired? I seemed to remember that, too, and remembered thinking the word sounded glamorous but then thinking it icky when I’d learned the Webster’s definition of it was “of a brownish-orange color,” which hardly sounded attractive—which was in direct opposition to my own curly black hair and brick-brown eyes.

I hated her already.

The bitch probably didn’t even have any cheesy cellulite on the backs of her thighs. It would be nice to be able to say I was too young to worry about cellulite, but genetics will out and mine had outed itself post-puberty in an unpleasant way. Oh, nothing too major, just enough to make the idea of appearing on a beach in a bathing suit somewhat less than confidence-building.

Feeling more disgusted than I’d expected to feel, I put aside #1 and picked up #56, the one with the pagoda on the cover, and turned to page one again.

Nancy was discussing some drink called Pearl Powder with friends Bess and George.

I remembered being confused by George when I was a little girl. Obviously, George was a boy’s name, and yet whenever there were pictures of the girls with Nancy’s boyfriend Ned in the book, I’d always think Ned was George and wonder where Ned was and who was that other girl? It was years before I sorted George’s androgyny out.

I grumbled. I didn’t have any friends.

Before Buster, I’d had a few friends, at least people to do things with and people to talk to when times got rough. But after I succumbed to Buster’s charms, I committed the other cardinal sin that girls make: I made the man not just the center of the universe, but the entire universe, and I let everyone else drift off to different galaxies.

So maybe I messed up that metaphor, but so what, because in that moment, I realized I no longer had any friends, not like Nancy did, not even a friend of not-readily-determinable sexual orientation like George.

You could say I felt sorry for myself. I knew my own choices and actions had led me to where I was, but I still felt sorry for myself.

If things had somehow worked out with Buster—not that I’d ever been able to define for myself, even before the bust-up, what would constitute things “working out” with a married man plus two kids—would I still be feeling sorry for myself at this point?

Probably, I figured. Because I would have still reached that critical state in a relationship where you realize you’ve let all your friendships die and all you have left is the one relationship.

Not that I’d had any other experience with relationships.

Come to think of it, I’d had limited experience with friendships, too.

I glanced down that first page of #56 and saw that—omigod!—Nancy was still eighteen! How was such a thing possible? I was pretty sure that even Sherlock Holmes, over the course of his many adventures, had aged a few years. So how had Nancy managed to age not one year over the course of fifty-six mysteries? I quickly did the math.

Okay, I went to find my calculator.

Figuring it wasn’t a leap year—because what are the odds? Something like one in four?—I did the division. Let’s see…365 divided by 56 is…6.5178571. 6.5178571??? This…teenager was solving mysteries at the rate of one every six and a half days? What kind of a girl was she? Oh, man, was I sooo not her.

Talk about an overachiever.

But then, after I was annoyed for a really long time, I started to think, How cool!

Imagine having one incredibly long year, the most stretched-out year imaginable, with enough time to get right everything a person needed to get right. What would I do with such a year? I couldn’t change the past. But maybe in changing my present, I could change my future?

I looked at the calendar on the back of my bedroom door, kittens in Greece, the sole present I’d received from Aunt Bea for my birthday: it was April 26. So, calculator time again, I had already lost 116 days so far that year—it wasn’t a leap year—meaning I’d already blown the chance to solve 17.846153 mysteries. But hey, there were still 249 days left, so there was still the opportunity for me to solve the remaining 38.153847 mysteries.

Whatever they were.

If only I could get up to speed real fast.

Actually, I was beginning to think that even I should be able to solve .153847 mysteries. It was the 38 part, I suspected, that would be the problem.

For the remainder of the two months until it was time for me to get on the plane to Iceland, I could read a book a day of Nancy Drew, leaving me five days at the end for shopping, packing and biting my nails to the quick.

Except for the day I went for the job interview, of course. Even someone desperate for a nanny who was willing to leave her life and go to Iceland wasn’t going to hire that nanny without first meeting her in person…. No matter what kind of wonderful things Ambassador Buster had said about her.

chapter 3

Then came the call. It was by one Mrs. Fairly, definitely a Mrs. who would never allow herself to be addressed as Ms., who requested I come to her master’s—master’s?—Park Avenue home for an interview. Clearly, this was a step up from Ambassador Buster Keating’s home, where I’d originally been interviewed and hired by his disinterested wife. I was now to be hired by a minion, which I figured meant I was moving up in the world.

Trying to answer that ever-popular euphonious question, WWNDD—What Would Nancy Drew Do?—I searched my practical wardrobe for the perfect persuasive costume to wear. Rejecting the casual allure of slacks and the confidence-inducing appeal of a dressy dress, I at last settled on a sensible plaid skirt and short-sleeved turtleneck I found in the back of my closet. I had no idea where these garments came from, could not for the life of me remember purchasing them, but when I looked in the mirror I saw they were doing the trick. Adding my mother’s pearls and unassuming flats to the picture, even though the flats gave me none of the height I so badly needed, I was ready to roll.

But first I had to run the gauntlet of Aunt Bea’s children.

“You look boring,” said Joe, the oldest at fifteen. “I’d never date you.”

“That’s a hideous combination,” said Elena, thirteen.

“Who would ever wear pearls with plaid?” sniffed Georgia, nine.

I was tempted to tell her that I was pretty damn sure Nancy Drew would wear plaid and pearls on an interview—hell, Nancy, who always wore gloves when she went out, but for entirely different reasons than why I ever did, would have undoubtedly worn gloves, too—but I didn’t want her to think I was crazier than she already clearly thought me. Plus, I still awaited Aunt Bea’s verdict.

She looked at me long.

“I…like it,” she finally said.

And that scared the shit out of me more than anything that had gone before.

When someone whose taste you don’t respect thinks that whatever you are wearing is the bee’s knees, chances are you’re making a fashion faux pas from which your image is unlikely to recover.

I grabbed a leather bag, black with brown suede trim, that was more satchel than purse, and was gone.

The living room I was led into by an actual liveried servant was big enough to fit Aunt Bea’s entire first floor into and it was quickly obvious that someone around here had an overly enthusiastic appetite for French furniture. Not that I’m particularly heavy, carrying no more extra baggage than the obligatory all-American extra ten, but when the servant indicated a Louis-something chair to me, and I felt the skinny legs wobble back and forth on the slippery marble floor beneath me, I found myself wishing for something more sturdy.

Mrs. Fairly turned out to be as old as Aunt Bea looked, with a staid black dress and her own pearls on—ha! Thank you, Nancy Drew!—that somehow reflected back the glow of her bluish white hair. She also carried an extra twenty pounds to my ten and was shorter than me, which is always a shocker.

I’ve spent my life thinking of my height more in terms of the technical—“I am a short person”—rather than in practice, because I’ve always felt taller and indeed all my life have been told, except by my family, that I don’t look that short, and that I have a much taller personality, whatever that means; even people who remember the commercials I made as a child, upon meeting me, never fail to comment, “You didn’t look like a short child!” Again, whatever that means.

“What religion are you?” she asked.

I would have guessed it was against some kind of law to ask a prospective employee about religious affiliation, unless of course you were hiring a bishop or a rabbi, but questioning the legality of her business ethics right off the bat hardly seemed the best tactic to secure me the position I wanted.

“Jewish,” I said.

“I see,” she said.

I wondered what she was seeing, endeavored to at least look like I was waiting patiently for some kind of elucidation.

“It’s just that,” she hesitated, “Iceland is such a…not-Jewish place.”

“Is that a problem?” I asked, wanting to kick myself even as the words were leaving my stupid, stupid mouth. Did I want the job or didn’t I? Why raise the issue, why say the word problem for her? Let her do it if she was going to do it.

“Oh, no, no,” she pooh-poohed. “I mean, after all, with that hair alone, not to mention the lack of height—” she eyed me up and down in no time at all “—you’re bound to stand out.”

This from a woman who was shorter than me and had blue hair?

But I kept my thoughts to myself.

“Challenges can be good,” I said, “for me and for Iceland.”

She smiled for the first time.

“You’re a little plucky,” she said, “aren’t you? I kind of like that.”

“Are Icelanders prejudiced?” I couldn’t stop myself from asking.

“Not at all,” she said. “They’re just all tall. And blond. And not Jewish.”

Until she’d brought up the subject of my religion, it hadn’t occurred to me to wonder that it might be strange to be a short, dark-haired Jew in Iceland. Maybe I hadn’t thought about the last so much because Judaism had never been a salient feature of my existence and was more like one of the less prominent lines on my résumé, like my high-school job at Dunkin’ Donuts.

In fact, it wasn’t until I was eight that I even learned I was Jewish and even then it was by accident.

Aunt Bea had just given birth to Joe, her first, and they were getting ready to baptize him. I was curious about the process, having never seen one before.

“Why would you know anything about it?” Aunt Bea had asked me in a rare unguarded moment. “Your mother was Jewish.”

I had known so little about my mother, other than that she’d died while having me. Women aren’t supposed to die in childbirth anymore, all the books tell you that it just doesn’t happen, but sometimes it does.

A decade before, I’d been a fan of the TV program E.R., until one night when I saw an episode called “Love’s Labors Lost.” It was about a woman who goes into the hospital to have a baby and everything goes wrong, one thing after another, until the woman dies. It was like they were playing the story of my birth, and after that I could never watch the show again, had no interest in any medical show or movie of any sort.

After my mother’s death at the moment of my birth, my father raised me until I was three. It was at that point that the constant reminder I represented to him of my mother, whom he had loved dearly, became too much for him. I was sent to live with Aunt Bea and Uncle Thornton, while my dad departed for Africa where he pursued work as an archaeologist. He wrote often, and came to visit a couple of times a year, his visits always initially having the forced formal feel of royalty calling. I cherished those visits, kept what warm moments transpired during them locked in a special treasure chest in my heart. But it always seemed that no sooner had we got used to one another once more, he was off again.

Uncle Thornton was kind to me in the ways that Aunt Bea was not, but when he died not long after their third child was born, I was left without an ally in the household. Aunt Bea was of a mind that I needed to earn my way there and the form that earning took was in helping to care for her three spoiled children. The upside was that in caring for them, I learned a trade that would help me care for the children of others, like now.

Still, finding out I was Jewish had come as a surprise, not necessarily an unpleasant one, but a surprise nonetheless. Once I knew, I clung to it as the only remaining legacy, other than the pearls, of my mother. Aunt Bea tried to shrug it off as some kind of obstinate whim I had taken into my head, and there was no one to teach me about my religion, but I clung to it all the same. I might not practice it very much, might not know enough about it, but it was a part of who I was, where I came from, who I’d always be.

Mrs. Fairly wanted to know some more about my experience with children, so I told her about my years helping Aunt Bea raise her three, neglecting to mention the parts about those three abusing me in every way their evil little minds could come up with.

At least, I thought, there had never been any red bedroom for them to lock me in.

“Children can be a wonderful challenge,” I told Mrs. Fairly. “I like challenges. I like wonder, too.”

If she thought that last was odder than something most people would say, she didn’t let on.

“Would you like to meet Annette now?” she inquired.

I looked at her questioningly.

“You did realize,” she said, “when you applied for a nanny position, that you’d be caring for a child…didn’t you?”

Apparently, she had her own plucky side.

“Annette,” she told me, “is the little girl you’d be caring for.”

When I nodded my consent, Mrs. Fairly summoned the liveried servant who in turn summoned an older woman in a tweed skirt and sweater set who entered the room holding the hand of a small girl, about age six, who was dressed in an old-fashioned pink dress that had puff sleeves with a white apron on it. The girl had dark curls, not so different from my own, and a spark of mischief in her dark eyes that would not be quenched, I suspected, no matter how serious those around her might get.

Annette quickly curtsied when she was immediately before me and tilted her head to one side as we were introduced by Mrs. Fairly.

“What kinds of things will you teach me?” she asked. “Are you good at geography? Math?”

I wondered how the little imp had read my mind so quickly and seen into my shortcomings.

I shook my head slowly, twice.

“I’m afraid that neither of those things is my strong point,” I confessed.

“Good,” she laughed, “since I am not good at them either and I would hate to have a nanny who was going on all the time about places and numbers. But…what are you good at?”

“Words,” I said. “I’m very good with words, language. Anything to do with reading, writing, I’m your girl.”

She laughed again, apparently delighted at the idea of me being her girl rather than the other way around.

I was puzzled though. Even though Mrs. Fairly had neglected to introduce me to the woman accompanying Annette, I knew instinctively this woman was not the child’s mother and must in fact be her nanny. She was too stereotypically caretaking to be anything else.

Apparently, though, I was in a houseful of mind readers, for Mrs. Fairly said next, “Sylvia has no wish to go to Iceland. That is why the master has had me look for a replacement.”

I did so wish she would stop referring to him as “the master.” Give her a humpback, crooked teeth, make her a man and put her in a castle, change her accent, too, and I’d swear I was sitting there with Dr. Frankenstein’s assistant.

“That will be all, Sylvia,” Mrs. Fairly said, indicating they could go.

I was curious: Why wouldn’t Mrs. Fairly, who seemed to be an uber competent woman, take care of Annette in Iceland? Was she perhaps staying behind in New York?

“Oh, no,” Mrs. Fairly answered after I voiced my questions aloud. “My job is to see to the general running of the household. I couldn’t possibly also be expected to be solely responsible for a small child myself. What sort of person could do both jobs at once?”

It was on the tip of my tongue to answer “a lot of mothers,” for I had read of such creatures in books and seen the role acted sometimes in that way on television and in movies, but I doubted snippiness would win me the job; pluckiness, perhaps, but not snippiness.

“I do hope you are chosen to come to Iceland with us,” Annette said, turning at the door. “We could have a lot of fun together.”

I somehow doubted that Mrs. Fairly’s greatest concern was that the new nanny be “fun.” Indeed, I somehow suspected that such a feature might prove a detriment in her eyes, for hadn’t she presumably hired the stern Sylvia? But at least she must be able to tell, obviously, that Annette and I would get along, which must surely be some kind of selling point when one is entrusting a precious young charge into the hands of a new nanny.

Mrs. Fairly studied me curiously once the other two were gone.

“Don’t you have any questions for me?” she asked. “Usually, it is normal for prospective employees to have some questions.”

Shit! I wanted to appear normal, but what to ask, what to ask…

I was sure if Nancy Drew were sitting in this wobbly chair, she’d know exactly what to ask. Of course, if she were sitting in this chair, I doubted it would have the audacity to wobble under her.

Nancy Drew would probably ask sensible questions: what her responsibilities would be, what was expected of her. She’d probably leave off asking to last—but she would definitely ask, being a practical girl and the daughter of a lawyer—about things like benefits, if they covered dental. Of course, if an injured carrier pigeon suddenly flew into the room, Nancy would undoubtedly wire the International Federation of American Homing Pigeon Fanciers in order to give them the number stamped on the bird’s leg ring since, as she’d pointed out in The Password to Larkspur Lane (#10), all homing pigeons are registered by number so their owners can be traced. Then she’d feed the bird water with an eyedropper, fill a box with wild bird-seed and notify all and sundry that carrier pigeons had been clocked at a mile a minute from Mexico City to New York. How did she know all these things? Was it just good instincts?

“Who is my employer and what does he do?” I blurted.

“His name is Edgar Rawlings…” She smiled, as though I should know whom she was talking about. “He’s to be the new United States ambassador to Iceland.”

Crap! I thought. Not another ambassador!

What were the odds? Then I remembered that the first time I’d found myself in the employ of an ambassador, an agency had placed me there. This time, on the other hand, I’d found the ad in the paper all on my own. I thought about the oddness of the coincidence, reeled at the notion of putting myself through this déjà vu. It was like the universe was playing a perverse trick on me, forcing me to repeat parts of my past. I supposed I could always turn down the position, provided it was even offered to me. But I had really liked Annette…

Mrs. Fairly misread the cause of my dismay.

“Don’t all countries have an ambassador? Surely,” she said, “even Iceland needs an ambassador, doesn’t it?”

She was asking me? I didn’t even know anything about Iceland. I mean, I knew that it was supposed to be completely dark there part of the year, completely light another part, but I had no idea what part I’d be flying into or if I’d indeed be flying into anything, if I indeed had landed the job.

“And is there a Mrs. Ambassador Rawlings?” I asked.

“Oh,” she said sternly, “you don’t need to know about her.”

Well, that sounded ominous.

“Now, then.” She leaned forward in her chair. “Why don’t you tell me why it was you left your last position.”

chapter 4

Icelandair must be the greatest airline in the world. The flight attendants wear these soothing uniforms that are kind of cool, they’re actually nice to the passengers and they give you real food, none of that “here’s your one-ounce bag of peanuts you’ll never be able to open and four ounces of soda and don’t you dare ask for the whole can, what else could you possibly need?” crap.

I was just getting ready to tuck into my salmon and grilled baby vegetables when my aisle mate, an elderly gentleman with not much hair, steel glasses and a lot of polyester recognized me.

This still happened occasionally, even though it had been sixteen years since I’d made the last commercial. It was the hair, the unruly black curls, and the quirky curve to my smile the few times I still smiled. At age three, right after my father had left me with Aunt Bea, that quirky curve had been deemed visually precocious, hence the casting director’s decision to select me as the face to represent Gubber Snack Foods. I was the Gubber Snack Foods Kid, had been spotted for my potential when Aunt Bea and I had been squashed next to the casting director on the subway.

“That child has amazing hair!” the casting director, Mort Damon, had enthused.

“If you like lots of hair on a little girl,” Aunt Bea had said.

“And that smile!” Mort Damon continued as he had begun. “It’s like looking at the Mona Lisa if she were a dwarf!”

Mort had given Aunt Bea his card and Aunt Bea had reluctantly accepted it.

“Don’t let this go to your head,” she’d cautioned after we’d answered the formality of a casting call and been called. “But this will be a way for you to earn your education. Not that I don’t think your father would be willing to pay, but you never know what might happen with an archaeologist.”

Gubber Snack Foods was supposed to be the perfect organic alternative to the overprocessed, oversugared foods for kids that lined the supermarket shelves. And a new generation of moms, working harder all the time both in and out of the home, had gratefully reached for it.

My big line, the one I intoned at the end of each commercial, having made sixteen commercials for various products in the line from the time I started until the time I turned seven, the words bubbling out of my organic chocolate-smeared mouth?

“It’s Gubberlicious!”

Four years later, at age seven, despite the fact that I was small for my age, I was deemed too old to hawk the product. Personally, I think it was because I stopped being cute. But whatever the reason, I counted myself lucky. Unlike other child stars who had difficulty adjusting to a life where they were no longer treated as special I had never been allowed by Aunt Bea to be treated as special in the first place and so I had no overinflated ego to recover from.

The commercials were still aired occasionally, appealing to audiences in a nostalgic way, and I still received the odd residual check.

As I say, people still sometimes recognized me, based on the hair and curvy smile. It by no means happened often, but at least a couple of times a year, some stranger would say, “I know I’ve seen that smile before! But where…?”

As far-fetched as it might sound, that people could recognize you just from a smile, I understood it from firsthand experience. Home sick with mono for a month in high school, I’d watched more old movies than I’d ever watched in my life or would ever watch again. On my first day of freedom, I’d been walking down Broadway when I caught the eye of an older woman, meaning someone lots older than me, traveling in the other direction, and she smiled.

“I know you!” I’d shouted, unable to come up with a name.

If she’d been someone truly recognizable, like Meryl Streep, I would never have stopped her. I mean, how mortifying!

She stopped on the street, smiling indulgently.

I racked my brain, trying to place that familiar face.

“Toothpaste commercial?” I tried.

She shook her head, smiled wider.

It was that last smile that nailed it.

“Animal House!” The way I jumped up and down, clapped my hands, you’d think I’d just beat Ken Jennings on Final Jeopardy. “You were the girl who was twelve but looked eighteen!” I shouted, talking to her like I was telling her something she didn’t know. “You passed out at the frat house!”

She smiled again, nodded.

“Well,” I said, winding down now that the glitch-in-my-memory itch had been scratched, “that’s just great. Thanks. And, hey, you really do have the best smile.”

I’d continued on my way, never even learning her real name. It wasn’t until later that it occurred to me to wonder how often that happened to her.

I have to confess, I wasn’t as consistently gracious as she was with me when confronted with the whole “I know I’ve seen that smile before! But where…?” situation. If I was in a good mood, I shyly answered, “Gubber Snack Foods.” If I was in a bad mood, I said, “It must have been when I body-doubled for Julia Roberts.”

They’d look at my non-tall, non-lithe body in confusion and say, “No, I don’t think that was it…”

The reason I plucked Julia Roberts’s name out of the air was no accident. It was because she had that same kind of smile: you could block out the rest of her face and with no other clue guess, “That’s Julia Roberts!” Julia Roberts and I shared nothing else in common, but we did share that one thing: block-out-the-rest-of-your-face smiles.

Indeed, even Mrs. Fairly had recognized me, once she’d seen the Gubber Snack Foods gig on my résumé.

“I used to buy Gubber Snack Foods,” she’d said, just like everybody always says it, like they’ve performed some kind of accomplishment you should be impressed by and not the reverse. “Oh, not for myself,” she’d gone on, “but in a previous post, I’d had more direct responsibility for the children of the household. I tasted one of those Gubber Snacks once…” She leaned across conspiratorially. “Revolting.”

Indeed. But the checks had been good at least.

Now the man in the seat next to me, George Cranston from Staten Island, was saying pretty much the same thing, all of which I’d heard a thousand times before, or at least fifty.

“I can’t wait to get home after my trip and tell my grandkids I sat for seven hours next to a beautiful somebody who used to be on television.”

And, for some reason, I was not in the mood to spend seven hours reminiscing about my years as the Gubber Snack Foods Kid. With my luck, he’d make me say my famous line, the line that other kids had teased me about at every phase of my schooling, once they’d figured out who I was.

“I’m not who you think I am,” I said impulsively.

“No?” He looked crestfallen. “Are you sure?”

“Quite.”

“Come on,” he said. “Say, ‘It’s Gubberlicious!’ for me just one time. I’ll bet you’re her.”

“No, I’m not,” I said firmly. “I’m…I’m…I’m her doppelgänger. People just confuse me with her all the time, but I’m really not her. Hell, people probably confuse her with me all the time, for all I know.”

George Cranston from Staten Island pulled back at my use of “hell,” but he was curious enough that it didn’t stop him for long.

“So,” he said, arms crossed, “who are you that people should confuse you with her?” He said “her” like the Gubber Foods Kid was Madeleine Albright or something.

“I’m a writer,” I countered the challenge without thinking.

Shit, where did that come from? I asked myself timidly as soon as the words were out of my mouth.

Actually, I kind of knew where that had come from. Back when I’d been interviewed by Mrs. Fairly, I’d even intimated as much, shyly confessing a newfound ambition to one day write.

Well, I had to do something with my life, didn’t I?

“Why would you want to do that?” she’d asked, stunned.

It’s amazing how, if a person has no inclination to do a thing themselves, they have trouble understanding the attraction/fascination it might hold for others.

I recalled for her an article I’d read once in the New York Times—it’s amazing how much trouble being an avid devotee of the Times has gotten me into—that said that eighty-one percent of people polled said they thought they had a book in them. What other career could boast that kind of attraction? Surely lots of people might say they want to be doctors, but it was more for the BMW and the nebulous help-humanity aspect of it than the desire to be up to their elbows in O.R. blood, I was sure of it. And surely eighty-one percent of people were not lining up to be systems analysts. I’ll bet not even that many people wanted to be actors, despite the glamour, what with public speaking being the number-one phobia, up there ahead of death and spiders.

And yet so many people wanted to write, and not necessarily because they saw it as an easy path to fame and fortune, although surely there were those who thought that.

So why the high statistics?

It was, I thought, because of the almost universal desire to be heard.

I wanted to be heard, too.

But since I couldn’t even hold my own interest with the scribblings in my diary, I knew I had my work cut out for me if I wanted to take steps in that direction.

I wondered at my own audacity, the notion that I might have something worth saying. But I also knew that enough had happened to me—the death of my mother, the absence of my father, the whole sorry affair with Buster—to infuse my voice, however naive it might be at times, with a precocious wisdom.

Even if I only wrote for myself, but seriously, it might give me the catharsis I needed.

Apparently, George took my avowal of being a writer at face value.

As he droned on with an idea he had for what I should write next, a story he was too lazy to write himself but that he felt someone should tell, I found myself wishing Mrs. Fairly were in the seat next to me instead, but she’d flown on to Iceland a few days before with Annette, saying it would be best if they got situated and the master grew accustomed to having two more in the new Iceland house before adding me as a third.

George seemed offended I didn’t jump at his novel idea, even though I suspected he would have sued me penniless if I’d ever dared to try.

“So,” he said, still enormously miffed, “if you’re not going to write Travels with George for your next novel, then what the hell are you going to write?”

What, indeed?

And, more importantly, WWNDD about my annoying companion?

Reading all fifty-six of those books, I’d fast learned that people always started telling Nancy everything…just as soon as they met her! And, before long, Nancy could always read their minds. She was like the ultimate Mistress of Empathy.

So, WWNDD?

She’d be nice to the nosy old geezer, she’d listen to every boring thing he had to say, she’d answer his questions with complete politeness without giving anything important away.

“I’m not sure what I plan to write,” I said honestly. “That’s part of what I’m going to Iceland to find out.”

And it was.

Ever since I was a young girl, I’d flirted with the idea of being a writer, had even written a long story, Diary of the Wicked Aunt’s Girl, a roman à clef if there ever was one. Writing, mostly in my journal, was my way of making sense of the world. More importantly, perhaps, it was a way of getting outside of myself, of living the lives I was not smart enough or talented enough or brave enough to live. I might not be able to sing on key, but maybe one day I could write a character who was an opera singer or a rock singer, beset by trials and tribulations but finding love where and when it mattered most. Best of all, if I were a writer, I could write my own endings, whether I was in the mood for tragedy or joy. I could kill those who deserved to be killed, I could kill those I loved best in my fictional worlds just for the sake of creating great drama, I could love without fear.

The only problem was, I had yet to come up with an idea that moved me. Even Diary of the Wicked Aunt’s Girl, once I’d read it through for the twelfth time, didn’t seem like something anyone else would ever pay good money for, unless it was because they wanted an example of writing that was howlingly awful.

I burned it in the fireplace, but I never forgot the one great line of my young heroine, Carly Bongstein: “If I ever get out of here alive, with God as my witness, I’ll never eat pork chops again.”

But I knew in my young heart I was destined to write something far more important than Diary of the Wicked Aunt’s Girl, even if it turned out to be the kind of book that sold meagerly, the critics raving or ranting for naught. It wouldn’t matter, because I would have written something true, something that really mattered, if to no one else, then to myself.

The only problem was, I had no idea what that book might be about.

And that was part of why, at age twenty, I’d applied for the position of nanny at Ambassador Keating’s house. I thought it might be good for my would-be writer’s soul to seek out low-level employment, cocooning as it were, until I knew what to write about.

And now, having not been able to come up with the inspiration for My Great Novel during my years in the Keating household, I was winging my way to a new household in Iceland in the hopes that a change of scenery would finally do the trick.

But I still hadn’t a clue as to what I would write about and had said as much to Mrs. Fairly, said as much to George now.

Mrs. Fairly had taken it better than George.

George seemed to be of a mind that I was holding out on him, that I was some kind of paranoid freak, fearful he might steal my ideas and use them for lucrative gain, just as he undoubtedly imagined I wanted to steal his.

“Well, if you want to be that way about it,” he huffed, reaching into the pocket hanging from the back of the seat in front of him in order to retrieve the reading material he’d stowed there earlier as insurance against the boredom of our long flight.

When he’d first put his reading material there earlier as we’d been settling in, I hadn’t bothered to take note of the specifics, concerned as I was at the time with arranging for my own comfort. Contacts out and glasses in to prevent dry eyes? Check. Shoes off to give my feet maximum comfort until such time as I might need to use the restroom with the no doubt urine-stained floor? Check. My copy of Shirley Hazzard’s Transit of Venus, the brass Poe bookmark—“Those who dream by day are cognizant of many things which escape those who dream by night,” the brass of which had set off the metal detector at airport security—firmly lodged at page 52? Check.

But now, for some reason, I was dead curious as to what George would deem appropriate in-flight reading material.

I stole a surreptitious glance.

It was Nancy Drew, #47, The Mysterious Mannequin.

He must have heard me gasp, because he looked up.

“Something wrong,” he asked, “Ms. Writer?”

“It’s just that…”

“Yes?”

“Oh. It’s just that I didn’t expect to see…”

“See what? Someone reading Nancy Drew on the way to Iceland?”

I hesitated, nodded.

“Ha!” he snorted, turned back to his book. “Shows how much you know.”

“What does that mean?” I pressed.

But my aisle mate was no longer interested in engaging in polite discourse with me. Apparently, I’d somehow managed to offend his delicate sensibilities one too many times.

“It’s just that,” he finally answered, not even deigning to lift his eyes from the dark print on the page, “if you’d ever been to Iceland before, you’d know better than to wonder about such things.”

I tried to immerse myself in Ms. Hazzard, but it just wasn’t cutting it. At the right time, I knew I’d love what I was reading, admire it intensely. But I was on a plane to Iceland, for God’s sake, had no idea what I was getting myself into, and probably the only reading that might have worked for me right then was brain candy.

Quickly, I learned that the SkyMall magazine was not the answer, either. And so, for a brief time I tried to read Nancy Drew over George’s shoulder, but he caught on fast, protectively hunching over the book and cradling the page with his right arm, like we were in grade school and he was the smart kid preventing the unprepared kid—that would be me—from cheating.

Sighing, I wished once again that Mrs. Fairly were my aisle mate instead of the dyspeptic George. True, they’d both recognized me as the Gubber Snack Foods Kid, although I’d successfully deflected George into believing I was not—some success!—but at least Mrs. Fairly had remained cheerful about it throughout the whole thing, whereas George…

Of course, Mrs. Fairly had only been peripherally interested in me as a former commercial child star. Yes, more than her interest in me as that had been Mrs. Fairly’s interest in me as the woman who used to be employed by Ambassador Keating.

What had been the story behind my employment? What had it been like there? Why had I left?

As I mentioned earlier, I had sought out employment in the Keating household as a refuge from both my claustrophobic situation in my aunt’s house and as a way to bide my time until a novel grew inside my brain.

My interview with Mrs. Keating had been far different than the one I’d more recently survived with Mrs. Fairly. Mrs. Keating, a tennis-playing tax attorney staunchly committed to loopholes and her weak backhand, had drilled me like she was a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and I was someone who had applied for the job of, well, ambassador.

Alissa Keating was pretty enough, but only in the way of women who have enough time and money to ensure they look that way. Without the bells and whistles and bows, she’d have just looked like anybody else who wasn’t really such a much.

Not that I’m trying to be catty here, just stating fact.

Anyway, Alissa needed a new nanny for her two kids because the last one “had left under unpleasant circumstances.”

Her face got all pinched when she said that, kind of like a golden raisin, and I suppose I should have questioned her further on it, but I just assumed that my predecessor had been a thief or incompetent or both. Since I was not a thief, and hopefully not incompetent, I figured I would suit the Keatings just fine.

Then Alissa brought in the kids for me to meet them.

Stevie, the girl, named for the sultry singer from Fleetwood Mac, who Alissa claimed her husband adored, was five at the time and was cute and bouncy, all blond curls and laughing glee. Children of neglectful parents—and I would indeed come to learn over the next three years that the Keatings were neglectful parents—are often sad little creatures, cynical before their time. But I’d long known there was the rare exception to that rule, kids who remained perky and resilient despite a cruel or indifferent upbringing. I knew these characteristics, could recognize them in another, because I possessed them myself.

The boy’s name was unfortunately Kim, ill advisedly named after the Kipling character by his mother, who obviously had not stopped to think that her literary pretensions might get the crap beaten out of her son later on in life. Kim was three at the time, a dour towhead with sad blue pools for eyes with too-long lashes who had not managed to become as resilient as his sister.

I liked the kids well enough on first meeting and they seemed to like me, with even Kim allowing a single tentative smile in my direction, like maybe he thought, Okay, so you’re being nice now, but how long will that last? How long will you last?

Alissa said I’d be expected to make sure the kids ate breakfast and dinner, make sure they got off to school okay and to all their extracurricular activities—there was a lot of ballet and soccer and that early-violin thing all the rich New York kids go to that I can never remember the name of, Samurai or something—and that when at home, she did not want them watching TV; she wanted me teaching them more important things all the time.

“Um, I’m not very good with math or geography,” I confessed, figuring it was best to get that out of the way so she could decide against me without wasting any more time.

That brought her up short for a minute, but only a minute, since three years earlier a good nanny had been hard to find, unlike now when a good position was hard for a nanny to find.

“I suppose that could be okay,” she finally said. “They can get some geography from their father. I’m pretty sure he keeps a map of some kind in his office. And they’re already the genetic recipients of good math from me.”

Alissa stressed that she wanted someone who would live in, that she needed someone seven days a week because she and her husband went out a lot and she did not want to disrupt the children by having them handed off to different sitters all the time.

I said that would be fine and it was. I wanted to get out of Aunt Bea’s house but, despite my own money, did not feel ready to live on my own. At least in the Keating household there would be the distraction of a job to do. Plus, I loved children.

“I don’t want a nanny,” said Alissa, “who is more interested in her own social life than in taking care of my children.”

I could have said that it seemed that she was more interested in her own social life than in taking care of her kids, but I held my tongue in an effort to come across as employable. So instead I said:

“That won’t be me. I have no social life.”

She gave me a once-over that said she was hardly surprised, for I had indeed worn the most sensible clothes plus no makeup for the interview, but then all of a sudden she did look surprised, snapping her fingers three times, as if she was trying to come up with something.

“The Gubber Snack Foods Kid, right?” she accused, pointing to me on the last snap.

In the instant after Alissa snapped and pointed, it was clear from her look that she thought I’d come down in the world, lookswise, since my last commercial. Well, that had been sixteen years ago.

“I guess they have someone come in and do makeup and stuff for those things, huh?” she said, in words that could have implied sympathy but didn’t.

I just shrugged.

But I could see in the next minute, by the acquisitive gleam in her eye, that if nothing about my résumé had clinched the job for me earlier—surely my lack of geography and math hadn’t exactly won me points, nor had her children’s immediate liking of me seemed to make an impression on her in any way—this had. Alissa Keating would enjoy nothing more than having friends and colleagues learn that she kept a former child star—even if all I’d done was make a few stupid commercials—as a subordinate in a tiny bedroom in her household.

I could just hear her at the tennis club now.

“Can you believe it?” Alissa would ask. Thwack! “‘It’s Gubberlicious!’” Thwack! “Yup! I’ve got her right up in my attic!” Thwack!

And, okay, I hadn’t actually seen the tiny bedroom at that point, but I could certainly guess.

Not long after her victorious gleam, the master of the household entered the kitchen where she had been interviewing me, walked by us without a glance, retrieved a foreign beer from the refrigerator and, with one testosterone-charged flick of the wrist, used a bottle opener to shoot off the cap. Turning, bottle to his lips, he took me in for the first time and I him.

It’s no overstatement to say that Buster Keating was the most beautiful man I’d seen in person up until that life-changing moment of my life. The rich dinners he’d undoubtedly consumed at diplomatic get-togethers had done not a trace of damage to his tall, muscular physique, and whatever tennis he himself played had only served to strengthen the structure into hardness, like a da Vinci model—I’m talking about the carved men of the sculptures here—every line and sinew defined. He had a shock of dark hair that defied the well-trimmed look one would expect in a diplomat, instead giving him the perpetual appearance of someone who had just climbed out of bed, a bed in which he and whoever his lucky partner was had no doubt had great sex. His brown eyes were to die for, his jawline like something a superhero couldn’t dent. When he smiled, the flash of white was almost obscene, both in intensity and implied invitation.

Of course, Buster was about twenty years older than me, but that didn’t matter. Why should it? Anyone could see that he was in a league I could only dream about, a league I’d never even seen before.

“Hey, you’re new,” he said before taking a slug of his beer.

It never occurred to me, in that moment, that his reaction could be anything more than that of the habitual flirt. I’d met people like Buster Keating before. Not necessarily bisexual, they couldn’t help themselves from flirting with every single person they came across, man, woman or animal. He probably flashed that same smile at his secretary, whether she was hot or not, at the carrier boy who delivered important papers to his office, at the schnauzer on the corner. For him, such a thing was merely a Pavlovian response; I was sure of it. There was nothing special to be read in his reaction to me; I was sure of that, too.

Alissa Keating was apparently sure of it, as well, for, without even turning to look at her husband, she said, “That’s right, Buster. Charlotte is the new nanny.”

And so it started, both my job in the Keating household and my ruinous affair with Buster.

Oh, I don’t mean to imply that it started right that minute. The onset took much longer than that. But, really, it kind of did.

The first several months there, I had hardly any contact with Buster at all, nor with Alissa for that matter. Since Buster spent a large part of every year either in Washington or at the foreign embassy to which he had been posted, he was mostly at home only on weekends and sometimes not even then. As for Alissa, she was too busy being everything but a mother to be a mother; that’s what she had me for. And so, most of my dealings with them were through the daily notes Alissa left for me on the butcher block in the kitchen, a knife always stuck in the top of the note so that no stray wind could ever blow her precious words away, notes filled with instructions on nutrition and scheduling recommendations for Stevie and Kim.

“Five fruits and vegetables each and every day, Charlotte. Even with your math-challenged mind, you can count that high…right?”

“Fifteen minutes of TV in the morning and fifteen at night. That’s it. They don’t call it the idiot box for nothing…right?”

“That last piece of chocolate cheesecake is mine…right?”

There were times I thought there must be better uses for that sharp note-stabbing knife than the purpose it was being used for.

And so, before another day had passed following my interview with Alissa, my life began to be filled with the education of small children, with shopping for birthday parties and making sure granola bars and juice boxes were in backpacks, with tutus and Samurai violin lessons.

It didn’t take many more days to pass before I started to fall in love with those kids. It wasn’t so much that they were particularly charming, certainly Kim wasn’t, but there was something so vulnerable about their orphans-within-a-two-parent-household circumstances. If their parents would not pay enough attention to them, then I would let Stevie play with what little makeup I owned, I would learn how to play games involving balls and things so I could teach Kim how to play, too.

It may not have been anybody’s idea of the Ideal Life, but it had become my life and it was sufficient.

The bedroom they gave me was in the far corner of the penthouse, a tiny box of a room—see? I had guessed that would happen!—that I suspected had been meant as an extra storage closet. It wasn’t so bad, though, not like what I imagined would be the airless, lightless, spiderweb-infested lodgings of any nanny living in the suburbs. I had a bed, a lamp to read by, there was even a TV, if I were so inclined, which I rarely was. So what if the room was a shade of yellow I detested; I was too timid to complain.

All households with small children have their routines. But the Keating household really didn’t have a routine that involved both parents and children for six out of the seven days of the week.

The only thing Alissa could be depended upon to do with her children was to take them out on Saturday afternoons. They invariably left at 1:00 p.m. and would remain gone for three to four hours, no more, never less. Their routine was also invariable: lunch at a kid-friendly restaurant like Rumpelmeyer’s, a visit to the toy store FAO Schwarz when it was still there, the big Toys “R” Us when it replaced the other and a final stop at some educational place, the planetarium or the Museum of Natural History.

The first few Saturdays that Alissa took the kids out for their afternoon outing passed unexceptionally. Even though I had told myself I would spend my three hours off a week working on writing something, anything, I instead met my own friends for lunch and shopping, Helen and Grace, my closest girlfriends.

Take care of kids for 165 hours; eat, shop for three. Take care of kids for 165 hours; eat, shop for three. If nothing else, the routine that I was forced to follow was improving my math skills.

But then a Saturday came when I woke with a stomach bug, leaving me no choice but to complete the remaining three of the 168-hour weekly cycle in my room, with no more than golf on the tiny TV to keep me company.

Then a knock came at the door and I suddenly had company.

“May I come in?” Buster poked his head around the door. “I didn’t hear you leave today so I thought you might be in here. Are you unwell?”

It seemed such a formal way to phrase the question—“Are you unwell?”—formal and utterly charming.

And when he came all the way around the doorway, the tray in his hands containing a Lenox bowl of chicken soup and a SpongeBob SquarePants plastic glass with a straw in it, he needed to do no more to sweep me away.

Even if I was lying down, he still swept me away.

“I just figured that—” he smiled sheepishly like a wolf “—even the girl who takes care of everyone else needs someone to take care of her sometimes.”

See what I mean?

When I had trouble sitting up, he set the tray gently on the floor and even more gently helped me, arranging the pillows behind me.

He even fed me with the spoon.

“Shh,” he said when I started to protest.

It just seemed so unseemly, my ambassador boss treating me with more tenderness than I’d ever seen him show to, well, his own children. It was inconceivable that he’d ever behaved so with Alissa.

“One day, when you’re feeling better, maybe I’ll let you take a turn and you can feed me.”

Combined with my feverish state, the image he’d put in my mind of me feeding him caused me to snort, which in turn caused the chicken soup that had been in my mouth to spray out my nose.

I must have seemed a charming companion.

Red-faced, I finished being fed in silence.

Afterward, he dabbed at my mouth, then eased me back down upon the pillows, smoothing the sheet over me.

“Would you rather be alone,” he asked, then paused before adding hopefully, “or would you like some company?”

All of a sudden, I hated the thought of being alone in that yellow room with nothing but golf, which I could neither stand nor understand, for company.

“Some company would be okay,” I said tentatively, “I guess.”

Aside from the narrow twin bed, the only other seating in the yellow room was an uncomfortable armchair with unpredictable springs that I only used late at night to sit at my desk, trying to convince myself I could someday be a writer.

Buster looked the question “May I?” And before I knew it, he had pulled the uncomfortable seat up alongside the bed, settling himself into it, despite that he dwarfed the thing.

“Do you know much about golf?” he asked.

I shook my head.

“It’s a silly game,” he said. “Useful, though. Would you rather watch or talk?”

“Talk would be good,” I said, “I guess.”

The chicken soup and juice had revived me enough so that I was wanting to cringe for having nothing better to say than “I guess” at the end of every response. In fact, I found myself hoping that I’d be interesting enough to command the attention of a handsome ambassador, even a married one.

He got up, switched off the set—there was nothing so exotic as a remote control for the nanny, certainly not one that worked—and sat back down again.

And then we talked.

Mostly, he talked, I should say, about his exciting career, about the books he liked to read. And yet, even though he did most of the talking, it felt as though we talked a lot about me. He would ask a question, like, “So what was it like, being on television in all those commercials at such a young age?” And then, when I mealymouthed with, “It was okay…I guess,” he amplified my answer with, “I know it must have been surprising. Oh, not that those commercials weren’t wonderful, because they most certainly were, in particular the one where you rubbed your tummy as you said your line. But how many people can say they were in a series of commercials? Not many, would be my guess.” He’d seen my stupid commercials! What could he have been at the time, his early twenties? What man that age would take note of, and later remember, such insipid commercials?