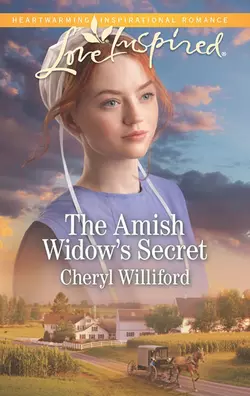

The Amish Widow′s Secret

Cheryl Williford

Second Chance at LoveWidow Sarah Nolt never expected another marriage proposal. She hardly knows the handsome Amish man who's come to help with her barn raising. Besides, they're both still mourning the loss of their spouses. But Mose Fischer needs a caretaker for his daughters, and Sarah needs to escape her father's oppressive rule. They agree to a marriage of convenience, but when Sarah moves to Mose's Amish community in Florida, she can't help falling for the strong, kind widower and his little girls. To create a family, they'll have to come to terms with their pasts…and the secret Sarah is unknowingly carrying.

Second Chance at Love

Widow Sarah Nolt never expected another marriage proposal. She hardly knows the handsome Amish man who’s come to help with her barn raising. Besides, they’re both still mourning the loss of their spouses. But Mose Fischer needs a caretaker for his daughters, and Sarah needs to escape her father’s oppressive rule. They agree to a marriage of convenience, but when Sarah moves to Mose’s Amish community in Florida, she can’t help falling for the strong, kind widower and his little girls. To create a family, they’ll have to come to terms with their pasts…and the secret Sarah is unknowingly carrying.

Mose looked up and saw Sarah hurry into the shop, her dress spotted with fat drops of rain.

Sarah looked young and happy. Mose’s heartbeat quickened as he walked toward her. “You picked a fine time to be out. It’s about to storm, from the looks of you.”

Sarah whirled at the sound of his voice and rushed over to him. “Mose, the cart ride was wonderful. I felt like a child again, the rain hitting me in the face and the golf cart sliding on the pavement.”

He pulled his handkerchief from his pocket and gently wiped her face dry, her eyes sky blue and shining at him. He fought down the urge to kiss her; his feelings for her were becoming more obvious to him every day.

“I’m sorry I dampened your handkerchief,” she apologized.

“Silly girl. That’s why I carry the rag. To help beautiful damsels in distress.” He heard himself flirting, like he might have done as a young man of nineteen.

Sarah was turning him into a schoolboy again. And he liked it.

CHERYL WILLIFORD and her veteran husband, Henry, live in South Texas, where they’ve raised three children, numerous foster children, alongside a menagerie of rescued cats, dogs and hamsters. Her love for writing began in a literature class and now her characters keep her grabbing for paper and pen. She is a member of her local ACFW and CWA chapters, and is a seamstress, watercolorist and loving grandmother. Her website is cherylwilliford.com (http://www.cherylwilliford.com).

The Amish

Widow’s Secret

Cheryl Williford

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Take delight in the Lord,

and He will give you your heart’s desires.

Commit everything you do to the Lord.

Trust Him, and He will help you.

He will make your innocence radiate like the dawn,

and the justice of your cause

will shine like the noonday sun.

—Psalms 37:4–6

This book is dedicated to the memory

of my grandfather, Fred Carver,

who encouraged me to reach for the stars,

and to my Quaker great-grandmother,

Clarrisa Petch, who inspired me.

Acknowledgments (#ulink_efee5dce-c326-5d8b-b71c-7bae109d9b3d)

To my patient and understanding husband, Will, who read and critiqued way too many manuscript chapters and blessed me with honesty. To my eldest daughter, Barbara, who graciously gifted me with fees for contests and conferences. To the ACFW Golden Girls critique group, Liz, Nanci, Jan, Zillah and Shannon; you are loved. To Eileen Key, the best line-edit partner in the business. To Les Stobbe, my wonderful agent and mentor; to my amazing Love Inspired editor, Melissa Endlich, who believed in me; and last but not least, to my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, who has opened many doors, enabling this book to be written and published.

Contents

Cover (#u74a13e96-0f0c-566c-80b0-e61a19991c9c)

Back Cover Text (#u5746853d-4771-5727-ace2-3250d836013a)

Introduction (#ude0cbeff-e1f7-5ff4-9243-b18fb717f72a)

About the Author (#u27c09188-ce54-53f3-b3ea-f98cc89da6ca)

Title Page (#u5fd549ef-dcc8-53b9-a789-5f7ed0205a7f)

Bible Verse (#ud7907459-1c4c-574f-806e-138936cafd5a)

Dedication (#u6faaae8a-8c94-5125-b64d-c81722c5bdb9)

Acknowledgments (#ub220fe85-d913-507f-8b94-31f3e05db1ae)

Chapter One (#u92579988-babf-57f8-b24b-8d83cd32e9dc)

Chapter Two (#uf93d4b6e-6836-57ad-ac68-4c82106c3822)

Chapter Three (#u40eccc37-18bb-5654-9966-bde704d843ec)

Chapter Four (#ude573290-fc52-5fa3-b0ae-1825015beb2e)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_753b27ef-39cc-5458-9338-32ef17bad08a)

It was the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen.

Sarah Nolt couldn’t resist the temptation. Gott would probably punish her for coveting something so fancy. She allowed the tip of her finger to glide across the surface of the sewing machine gleaming in the store’s overhead lights.

She closed her eyes and imagined stitching her dream quilt. Purple sashing would look perfect with the patch of irises she’d create out of scraps of lavender and blue fabrics and hand stitch to the center of the diagonal-block quilt.

“Some things are best not longed for,” Marta Nolt whispered close to Sarah’s ear.

Sarah jumped as if she’d been stung by a wasp. A flush of guilt washed over her from head to toe. “You startled me.” She shot a glance at her lifelong friend and sister-in-law—the two had grown up together and had even married each other’s brothers. Had Marta seen her prideful expression? All her life she’d been taught pride was a sin. She wasn’t convinced it was.

Compared to Sarah’s five-foot-four frame, Marta appeared as tiny as a twelve-year-old in her dark blue spring dress and finely stitched, stiff white prayer kapp. Marta’s brows furrowed. “It is better I startled you than your daed, Sarah. He’s just outside the door waiting for us. He said to hurry, that he has more important things to do than wait on you this morning. Did you do something to irritate him again? One day he’ll tell the elders what you’ve been up to and—”

“And they’ll what? Call me in for another scolding and long prayer, and then threaten to tell the Bishop how unruly a widow I am?” Sarah turned for one last look at the gleaming machine and moved away.

“If they find out about you giving Lukas money, you’ll be shunned. You know they’re looking for someone to blame and wanting to set an example since he ran away with young Ben in tow. Everyone believes they’ve joined the Englisch rescue house. The boys’ father is beyond angry. Nerves have become rattled throughout the community. People are asking who else is planning to leave.”

“I’m not joining if that’s what you’re thinking. I wasted my time by looking at a sewing machine I can’t ever have. I dream. Nothing more. How can that fine piece of equipment be so full of sin just because it’s electric and fancy? It’s made to produce the finest of quilts.”

Sarah shoved back a lock of hair and tucked it into her kapp. “Last week an Englisch woman used one of the machines for a sewing demonstration. My heart almost leaped out of my chest, Marta. You should have seen the amazing details it sewed. It would take a year or more for us to make such perfect stitches by hand. Daed needs money for a new field horse. If I had this machine, I could make quilts more quickly and sell them to the Englisch on market day. I could make enough money to keep my farm and eat more than cooked cabbage and my favorite white duck.”

“All you have to do is ask for help, Sarah. You are so stubborn. The community will—”

“Rally round? Tell me I must sell Joseph’s farm because a family deserves it more than a helpless widow. Nee, I don’t want their help.”

“Careful. Someone might hear you.”

Marta had always tried to accept the community’s harsh rules, but today her words of mindless obedience angered Sarah. “I will not ask for help and will not be silent. Will Gott finally be satisfied if He takes everything dear from me, including my dreams?”

“Ach, don’t be so bitter. Your anger comes from a place of pain. You need to pray. Ask Gott to remove the ache in your heart.” Marta took her hand and squeezed hard. “Since Joseph died you’ve done nothing but stir up the community’s wrath. You know what your daed’s like. He’ll only take so much before he lets the Bishop come down hard on you. You can’t keep bringing shame on the Yoder name.”

“I don’t care about my daed’s pride of name. Is his pride not sin too? I am a Nolt now, not a Yoder. I’m a twenty-five-year-old widow. Not a child. I will make my own decisions. You wait and see.”

“Meine liebe. The suddenness of Joseph’s death brought you to this place of anger and confusion. Don’t grieve him so. His funeral is over, the coffin closed. It was Gott’s will for Joseph to die. We must not ever question, Sarah. Joseph was my older brother, but I’m content to know he’s with the old ones and happy in heaven.”

Memories of the funeral haunted Sarah’s sleep. “I’m glad you are able to find peace in this rigid community, Marta. I really am. But I can’t. Not since Gott let Joseph die in such a horrible way. To burn to death in a barn fire is too horrible. What kind of Gott lets this happen to a man of faith? This cruel Gott has nee place in my life.” Sarah sighed deeply. Will I ever be happy again and at peace?

She reached out a trembling hand and grabbed a card of hooks-and-eyes and threw it in the store’s small plastic shopping basket that hung off her wrist. She added several large spools of basic blue, purple and black thread and turned back toward Marta, who stood fingering a skein of baby-soft yarn in the lightest shade of blue. “Do you have something you want to tell me?”

“Nee.” Marta’s ready smile vanished. “I’m not pregnant. Gott must intend for me to rear others’ kinder and not my own.”

Marta had miscarried three times. Talk among the older women was there would be no bobbel for her sister-in-law unless she had an operation. Sarah knew the young couple’s farm wasn’t doing well. There would be no money for expensive procedures in Englisch hospitals for Marta, even if the Bishop would allow it.

Sarah said, “I wish—”

“I know. I wish it, too. A baby for Eric and me. And Joseph still alive for you. But Gott doesn’t always give us what we want or make an easy path to walk.”

Heavy footsteps announced Sarah’s father’s approach. Both women grew silent.

“Do you realize the sun is at its zenith and a man grows hungry?” Adolph Yoder’s sharp tone cut like a knife. The short-statured man rubbed his rotund stomach and glared at his only daughter.

Sarah straightened the sweat-soaked collar of her father’s blue shirt and smiled, trying hard to show her love for the angry man. “I’m sorry, Daed. Time got away from us.” Sarah gathered the last of the sewing things she needed and tried to match his fast pace down the narrow aisle.

Her father stopped abruptly and turned toward her. His blue eyes flashed. “You must learn to drive your own wagon, daughter. Do your own fetching. Enough time has passed.”

“Ya.” Sarah nodded. He turned away and moved toward the door. She thought back to the times she’d begged him to teach her the basics of directing a horse or mending a wheel, but nothing had ever come of it. He had always been too busy trying to be both Mamm and Daed to her and her younger brother, Eric. She blamed herself and her mother’s sudden disappearance into the Englisch world on her father’s angry moods. Once again she wished her mamm had taken her with her when she’d left Lancaster County.

Joseph would have been happy to teach her to drive, but Gott had taken him too soon. Bitterness swelled in her heart, adding to the pain already there. Tears pooled in her eyes and slid down her cheeks as she thought of him. She brushed them away, not willing to show her pain.

Moments later the familiar woman at the checkout line greeted Sarah as she might an Englisch customer. “Hello, Sarah. How are you today, dear?”

“Gut, and you?”

“Oh, I’m fine as I can be,” she responded. “You’re buying an awful lot of thread. You ladies planning one of your quilting bees?”

“Nee, just stocking up.” Sarah emptied the small basket on the counter and began stacking the spools of thread.

“Well, you let me know if you need someone to help sell your quilts. I’ll be glad to place them in the shop window for a small fee. You do beautiful work. You should be sewing professionally.”

Distracted by her thoughts, Sarah tried hard to follow the older woman’s friendly banter. “Danke. I’ll speak to the Bishop’s wife and see what she says, but I don’t hold much hope. There are rules about selling wares in an Englisch shop. You know how strict some are.”

“Yeah, I do.” She patted Sarah’s hand.

Sarah’s father walked past and glanced at the two women. He hurried out of the shop, letting the door slam. His bad mood meant problems for Sarah. When riled, he could be very cruel. She had no one to blame but herself for his bad attitude today. She knew he grew tired of her lack of control and rule breaking. People were openly talking about her. She had to learn to keep her mouth closed and distance herself from the Englisch.

Sarah hurried out of the store and trailed behind Marta. Fancy Englisch cars dotted the parking lot. She made her way to her father’s buggy parked under a cluster of old oaks.

He stood talking to a man unfamiliar to Sarah. The man turned toward her as she approached. He wore a traditional blue Amish shirt, his black pants wrinkled and dusty, as if he’d been traveling for days. The black hat on his head barely controlled his nest of dishwater-blond curls. Joseph had been blond and curly-haired, too. Memories flooded in. Her heart ached.

Men from all around the county were coming today. The burned-out barn was to be torn down and cleared away. The man standing next to her father had be one of the workers who’d traveled a long distance to lend a helping hand. She often disapproved of many Amish ways, but not their generosity of heart. Helping others came naturally to all Amish. She honored this trait. It was the reason she’d helped the neighbor boys get away from their cruel father.

“Sarah,” Marta called out and motioned for her to hurry. Sarah picked up her pace.

“Come, Sarah! Time is wasting,” her father called out.

“Ya, Daed.”

The tall, well-built man smiled. She was struck by the startling blueness of his eyes and the friendly curve of his mouth. His light blond beard told her he was married. She gave a quick smile.

Marta stepped forward. “This is Mose Fischer, Joseph’s school friend. He came all the way from Florida to help us rebuild the barn.”

Mose Fischer took her hand. The crinkles around his eyes expressed years of friendly smiles and a good sense of humor.

Sarah wasn’t comfortable with physical contact, but allowed him to take her hand out of respect to Joseph. She returned his smile. “Hello. I’m glad to meet you.” She meant what she’d said. She was glad to meet him. She’d only met her husband’s sister, Marta. Meeting Joseph’s childhood friend made her feel more a part of his past life.

Adolph put his hand on Sarah’s shoulder. Touching her was something he rarely did, especially in public. “Sarah loves kinder. Perhaps you’d like her to care for your young daughters while you work?”

“If Sarah agrees, I’d like that very much.” Mose Fischer seemed to look deep into her soul, looking for all her secrets as he spoke. Why hadn’t his wife come to Lancaster with him? “I’d be glad to care for the bobbles, and I’m sure I’ll have help. Marta seldom gets a chance to play with kinder and will grab at this opportunity.”

Marta nodded with a shy laugh and smiled. “Just try to keep me away.”

“How old are the kinder?” Sarah grinned, happy for a chance to be busy wiping tiny fingers and toes. She’d be much too preoccupied to fret or watch the last of the barn come down.

“Beatrice is almost five and Mercy will soon be one. But, I warn you. They miss their mamm since she passed and can be a real handful.” Pain shimmered in his eyes.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know you were a widower. You were very brave to travel alone with such young daughters.”

“We came by train from Tampa, but my memories of Joseph made all the effort worth it. I didn’t want to miss the chance to help out his widow.”

“Where are you staying?”

“Mose and the girls will stay on my farm, and so will you.” Adolph gave Sarah a familiar glare.

“That’s fine. I can stay in my old room for a few days, and the girls can sleep with me.” Sarah nervously straightened the ribbons hanging from her stiff white prayer kapp. Since she was in deep mourning, her father knew she wanted to continue to hide herself at her farm, far away from people and gossip. “If that suits you, Mose.” She held her breath. She suddenly realized she needed to be around the girls as much as they needed her.

* * *

Dressed in a plain black mourning dress and kapp, her black shoes polished to a high shine, Mose could see why Joseph had chosen Sarah as his bride. There was something striking about her, her beauty separating her from the average Amish woman. She tried to act friendly, but he’d experienced the pain of loss and knew she suffered from the mention of Joseph. Greta had been the perfect wife to him and mother to his girls. After almost a year, the mention of her name still cut deeply and flooded his mind with memories.

“I hope they’re not a handful for you.” A genuine smile blossomed on the willowy, red-haired woman’s face. She looked a bit more relaxed. The heavy tension between Sarah and her father surprised him. Surely Adolph would be a tower of strength for her. She’d need her father to lean on during difficult times. Instead, Mose felt an air of disapproval between the two. He’d heard Adolph Yoder was a hard man, but Sarah seemed a victim in this terrible tragedy.

“I’ll bring the girls around in an hour or so, if that’s all right.”

“Ya. I’m not doing anything but cooking today. The girls can help bake for tomorrow’s big meal.” Sarah smiled a shy goodbye and followed Marta into the buggy. She pulled in her skirt and slammed the door. Through the window she waved, “I look forward to taking care of the kinder.”

“Till then,” Mose said, and waved as the buggy pulled onto the main road, his thoughts still on the tension between father and daughter.

Walking came naturally to Mose. He set out on the two-mile trip to his cousin’s farm and prayed his daughters had behaved while he was gone. Dealing with her own grief, he wasn’t sure Sarah was up to handling the antics of his eldest daughter. Four was a difficult age. Beatrice was no longer a baby, but her longing for her dead mamm still made her difficult to manage.

The hot afternoon sun beat down on his head, his dark garments drawing heat. He welcomed the rare gusts of wind that threatened to blow off his straw hat and ruffle his hair. Lancaster took a beating from the summer heat every year, but today felt even more hot and muggy. He would be glad to get back to Sarasota and its constant breeze and refreshing beaches.

A worn black buggy rolled past, spitting dust and pebbles his way. To his surprise, the buggy stopped and a tall, burley, gray-haired man hopped out.

“Hello, Mose. I heard you were in town.”

I should know the man. He recognized his face but struggled with the name. “Forgive me, but I don’t remember—”

“Nee. It was a long time ago. I’m Bishop Ralf Miller. It’s been five years or more since I last went to Florida and stayed with your family. I’ve known your father for many years. When we were boys, we shared the same school. I believe you’d just married your beautiful bride when your father introduced me to you.”

“My wife died last year,” Mose informed him. “Childbirth took her.” Saying the words out loud was like twisting a knife in his heart.

“I’m sorry. I had no idea.”

“There’s no reason you would know,”

“Nee, but it worries me how many of our young people are dying. I assume you’re here to help with Joseph Nolt’s barn clearing.”

“I just met his widow. Poor woman is torn with grief.”

“Between the two of us, I’m not so sure Sarah Nolt is a grieving widow. One of the men at the funeral said they heard her say Joseph’s death was her fault. The woman’s been unpredictable most of her life. Her father and I had a conversation about this a few days ago. He’s finding it hard to keep both farms going, and Sarah is stubbornly refusing to return to her childhood home. Joseph’s farm needs to be sold. If she doesn’t stop this willful behavior, I fear we’ll have to shun her for the safety of the community.”

Surprised at the openness of the Bishop’s conversation and the accusation against Sarah, Mose asked, “What proof do you have against her, other than her one comment made in grief? Has she been counseled by the elders or yourself?”

“We tried, but she won’t talk to us. She’s always had this rebellious streak. Her father agrees with me. There could be trouble.”

“A rebellious streak?”

“You know what I mean. Last week she told one of our Elders to shut up when he offered her a fair price for the farm. This inappropriate behavior can’t be ignored.”

“You’ve just described a grieving widow, Bishop. Perhaps she’s...”

Bishop Miller interrupted Mose, his brows lowered. “You don’t know her, Mose. I do. She’s always seemed difficult. Even as a child she was rebellious and broke rules.”

“Did something happen to make her this way?” Mose’s stomach twisted in anger. He liked to consider himself a good judge of character and he hadn’t found Sarah Nolt anything but unhappy, for good reason. Adolph Yoder was another matter. He appeared a hard, critical man. The Bishop’s willingness to talk about Sarah’s personal business didn’t impress him either. These things were none of Mose’s concern. He knew, with the community being Old Order Amish, that the bishop kept hard, fast rules. In his community she’d be treated differently. If she had no one to help her through her loss, her actions could be interpreted as acting out of grief. Perhaps the lack of a father’s love was the cause of his daughter’s actions. “Where is Sarah’s mother?”

“Who knows but Gott? She left the community when Sarah was a young child. She’d just had a son and some said raising kinder didn’t suit her. Adolph did everything he could to make Sarah an obedient child, like his son, Eric, but she never would bend to his will.”

“I saw little parental love from Adolph. He’s an angry man and needs to be spoken to by one of the community elders. Perhaps Gott can redirect him and help Sarah at the same time.”

“We’re glad to have your help with the teardown and barn-building, but I will deal with Sarah Nolt. This community is my concern. If your father were here, he’d agree with me.”

Mose drew in a deep breath. He’d let his temper get the better of him. “I meant no disrespect, Bishop, but all this gossip about the widow needs to stop until you have proof. It’s your job to make sure that happens. You shouldn’t add to it.”

“If you weren’t an outsider you’d know she’s not alone in her misery. She has her sister-in-law, Marta, to talk to and seek counsel. Marta is a godly woman and a good influence. If she can’t reach her, there will be harsh consequences the next time Sarah acts out.”

“I’ll be praying for her, as I’m sure you are.” Mose nodded to the bishop, and kept on walking to his cousin’s farm.

But he couldn’t help wondering, who was the real Sarah?

* * *

Beatrice squirmed around on the buckboard seat, her tiny sister asleep on a quilt at her feet. “I want cookies now, Daed.”

Mose pulled to the side of the road and spoke softly. “Soon we’ll be at Sarah’s house and you can have more cookies, but if you wake your sister, you’ll be put to bed. Do you understand?”

The tear rolling down her flushed cheek told him she didn’t understand and was pushing boundaries yet again.

“Mamm would give me cookies. I want Mamm.” An angry scowl etched itself across her tear-streaked face.

These were the times Mose hated most, when he had no answers for Beatrice. How can I help her understand?

“We’ve talked about this before, my child. Mamm is in heaven with Gott and we must accept this, even though it makes us sad.” He drew the small child into his arms and hugged her close, his heart breaking as he realized how thin her small body had become. He had to do something to cheer her up. “Let’s hurry and go and see the nice ladies I told you about. Sarah said she’d be baking today. Perhaps she’ll have warm cookies. Wouldn’t cookies and a glass of cold milk brighten your spirits?

“I only want Mamm.”

Tucked under his arm, Beatrice cried softly, twisting Mose’s heart in knots. His mother had talked to him about remarriage, but he had thrown the idea back at her, determined to honor his dead wife until the day he died. But the kinder definitely needed a woman’s gentle hand when he had to be at work.

His mother’s newly mended arm limited her ability to help him since the bad break, and now her talk of going to visit her sisters in Ohio felt like a push from Gott. Perhaps he would start considering the thought of a new wife, but she’d have to be special. What woman would want a husband who still loved his late wife? But he couldn’t become someone like Adolph Yoder either, and leave his young children to suffer their mother’s loss alone. Adolph’s bitterness shook Mose to his foundation. Would he become like Adolph to satisfy his own selfish needs and not his daughters’?

Deep in thought, Mose pulled into the graveled drive and directed the horse under a shade tree. Sarah Nolt hurried out the door of the trim white farmhouse, her black mourning dress dancing around her ankles. She approached with a welcoming smile. In the sunlight her kapp-covered head made her hair look a bright copper color. A brisk breeze blew and long lengths of fine hair escaped and curled on the sides of her face. The black dress was plain, yet added color to her cheeks. Mose opened the buggy’s door.

Beatrice crawled over him and hurried out. A striped kitten playing in the grass had attracted her attention. Mercy chose that moment to make her presence known and let loose a pitiful wail. Mose scooped the baby from the buggy floor.

Beatrice suddenly screamed and ran to her father, her arms wrapping around his leg. “Bad kitty.” She held out a finger. A scarlet drop of blood landed on the front of the fresh white apron covering her dress.

Sarah took the baby and tucked the blanket around her bare legs as she slowly began to rock the upset child. Tear-filled blue eyes, edged in dark lashes, gazed up at the stranger. “Hello, little one.”

Amazed, as always, that the tiny child could make so much noise, Mose watched as Sarah continued to rock the baby as she walked to the edge of the yard. Mose soothed Beatrice as Sarah moved about the garden with his crying infant.

Moments later Sarah approached with the quieted baby on her shoulder. “The bobbel has healthy lungs.” She laughed.

Mose ruffled the blond curls on Mercy’s head. “That she does. You didn’t seem to have any trouble settling her.”

“I used an old trick my grandmammi used on me. I distracted her with flowers.”

Beatrice looked up at Sarah with a glare. “You’re not Mercy’s mamm.” She pushed her face into the folds of her father’s pant leg.

“I warned you. She’s going to be a handful.” Mose patted Beatrice’s back.

Sarah handed the baby to Mose and dropped to her knees. Cupping a bright green grasshopper from the tall grass, she asked, “Do you like bugs, Beatrice?” She held out her closed hand and waited.

Beatrice turned and leaned against her father’s legs, her eyes red-rimmed. “What kind of bug is it?” She stepped forward, her gaze on Sarah’s extended hands.

Motioning the child closer, Sarah slightly opened her fingers and whispered, “Come and see.” A tiny green head popped out and struggled to be free.

“Oh, Daed! Look,” Beatrice said, joy sending her feet tapping.

Sarah opened her hand and laughed as the grasshopper leaped away, Beatrice right behind it, her little legs hopping through the grass, copying the fleeing insect.

Mose grinned as he watched his daughter’s antics. “You might just have won her heart. How did you know she loves bugs?

“I’ve always been fascinated with Gott’s tiny creatures. I had a feeling Beatrice might, too.”

Mose’s gaze held hers for a long moment until Sarah lost her smile, turned away and headed back into the house.

Chapter Two (#ulink_bdc5da87-44b8-5258-bee1-c428d8df5e5d)

Steam rose from the pot of potatoes boiling on the wood stove. The men would be in for supper soon and Sarah thanked Gott there’d only be two extra men tonight and not the twenty-five hungry workers she’d fed last night.

She glanced at the table and smiled as she watched Beatrice use broad strokes of paint to cover the art paper she’d given her. The child had been silent all afternoon, only speaking when spoken to. The pain in her eyes reminded Sarah of her own suffering. They grieved the same way—deep and silent with sudden bursts of fury. The child’s need for love seemed so deep, the pain touched Sarah’s own wounded heart.

Almost forgotten, Mercy lay content on her mat, a bottle of milk clutched in her hands. Her eyes traveled around, taking in the sights of the busy kitchen floor. The fluffy ginger kitten rushed past and put a smile on the baby’s face. Sarah saw dimples press into her cheeks. If she and Joseph had had kinder, perhaps they would have looked like Mercy and Beatrice. Blonde-haired with a sparkle of mischief in their blue eyes.

Joseph’s face swam before her tear-filled eyes. She missed the sound of his steps as he walked across the wooden porch each evening. His arms wrapped around her waist always had a way of reassuring her. She’d been loved. For that brief period of time, she’d been precious to someone, and she longed for that comfort again. Her arms had been empty but Gott placed these kinder here and she was grateful for the time she had with them.

“Would you like a glass of milk, Beatrice? I have a secret stash of chocolate chip cookies. I’d be glad to share them with such a talented artist.”

“Nee,” she said.

“Perhaps—”

“I want my mamm,” Beatrice yelled, knocking the plastic tub of dirty water across the table and wetting herself and Sarah’s legs.

Sarah stood transfixed as the child waited, perhaps expecting some kind of reprimand. There would be no scolding. Not today. Not ever. This child suffered and Sarah knew the pain of that suffering. She often felt like throwing things, expressing her own misery with actions that shocked.

Quiet and calm, Sarah mopped up the mud-colored water, careful not to damage Beatrice’s art. “This would look lovely hung on my wall. Perhaps I could have it as a reminder of your visit?”

Beatrice looked down at her smock, at the merging colors against the white fabric, and began to cry deep, wrenching sobs. Unsure what else to do, Sarah prayed for guidance. She knelt on the floor, cleaned up the child before wrapping her arms around her trembling body. “I know you’re missing your mamm, Beatrice. I miss my husband, too. He went to live in heaven several months ago and I want him back like you want your mother back.”

“Did he read stories to you at bedtime?” Beatrice asked, her innocent gaze locked with Sarah’s.

Their tears fell together on the mud-brown paint stain on Beatrice’s smock. “Joseph didn’t read to me, but he told me all about his day and kissed my eyes closed before I fell asleep.” The ache became so painful Sarah felt she might die from her grief.

“My mamm said I was her big girl. Mercy was just born and cried a lot, but I was big and strong. I help Grandmammi take care of Mercy. Do you think mamm’s proud of me?”

Sarah looked at the wet-faced child and a smile came out of nowhere. Beatrice was the first person who really understood what Sarah was living through, and that created a bond between them. They could grieve together, help one another. Gott in his wisdom had linked them for a week, perhaps more. Time enough for Beatrice to feel a mother’s love again.

She would never heal from Joseph’s death, but this tiny girl would give her purpose and a reason for living. She needed that right now. A reason to get up in the morning, put on her clothes and let the day begin.

The screen door banged open and Mose walked in, catching them in the warm embrace. Beatrice scurried out of Sarah’s arms and into her father’s cuddle. “Sarah likes me,” she said and smiled shyly over at Sarah.

Mose peppered kisses on his daughter’s neck and cheeks. “I see you’ve been painting again. How did this mess happen, Beatrice?”

“I was angry. I knocked down my paint water.” Beatrice braced her shoulders, obviously prepared to deal with any punishment her father administered.

“Did you apologize to Sarah for your outburst?”

“Nee.” Beatrice rested her head on her father’s dirty shirt.

“Perhaps an apology and help cleaning the mess off the floor is in order?” Mose looked at Sarah’s frazzled hair and flushed cheeks.

“Sarah hugged me like Mamm used to. She smells of flowers. For a moment I thought Mamm had come back.”

Sarah grabbed the cloth from the kitchen sink and busied herself cleaning the damp spot off the floor. She didn’t know what Mose might think about the cluttered kitchen. Perhaps he’d feel she wasn’t fit to take care of active kinder. She scrubbed hard into the wood. Maybe I’m not fit to care for kinder. She and the child had cried together. She was the adult. Shouldn’t she have kept her own loss to herself?

“I’m sorry I made a mess, Sarah. I won’t do it again. I promise.”

Sarah looked into the eyes of an old soul just four years old. “It’s time some color came into this dark kitchen, Beatrice. Your painting has put a smile on my face. There’s no need for apologies.” She smiled at the child and avoided Mose’s face. She felt sure he’d have words for her later. She leaned toward Mercy, kissed her blond head as she toddled past, checked her over and then handed her a tiny doll with hair the color of corn silk. “Here you are, sweet one. You lost your baby.” Sarah expected a smile from the adorable bobble, but the child’s serious look remained.

Sarah scrambled to get off the floor. Mose stood over her, his big hand outstretched, offering to help. She hesitated, but took his hand, feeling the warmth of his thick fingers and calloused palm. His strength was surprising. She felt herself pulled up, as if weightless. She refused to look into his eyes. She’d probably find anger there, and she couldn’t handle his wrath just now. She’d be more careful to stay in control around the girls.

“You’ve broken through her hedge of protection.” Mose leaned in close and whispered into Sarah’s ear. She looked up, amazed to see a grin on his face, the presence of joy.

“I just—”

“Nee, you don’t understand. You reached her, and for that I am most grateful.”

Sarah didn’t know what to say. She’d never received compliments such as this before, except from Joseph and her brother, Eric. Joseph had constantly told her how much he loved her and what a fine wife she made. Receiving praise from a stranger made her uncomfortable.

“I have supper to finish before my father returns. He likes his meal on the table at six sharp. If I hurry, I can avoid his complaints.”

“I’m sure he’ll understand the delay with two kinder underfoot.”

“You don’t know my father. He runs his home like most men run their business. I must hurry.”

Sarah prepared the table with Beatrice trailing close behind. She let the child place the cloth napkins in the center of each plate and together they stood back and admired their handiwork.

Beatrice glanced around. “We forgot Mercy’s cup.”

“I have it in the kitchen, ready for milk.” Sarah patted Beatrice’s curly head.

“And the special spoon she eats from.”

Sarah laughed at the organized child. Beatrice had the intensity of an older sister used to caring for her younger sister. “You’ll make a great mamm someday,” Sarah told her, moving the bowl of hot runner beans closer to her own plate. No sense risking a nasty burn from a child’s eager hand.

“Do you think my daed will be proud of me?” Beatrice looked excited, her smile hopeful.

Sarah pulled the girl close and patted her back. “I’m sure he’ll notice all your special touches.”

“My mamm said... I’m sorry. My grossmammi said I was to forget my mamm, but it’s hard not to remember.”

Sarah’s face flushed hot. How dare someone tell this young child to forget her mamm? Had her own mother missed her when she’d left the Amish community for the Englisch? She had no recollection of how her mamm looked. No pictures graced the mantel in her father’s house. Plain people didn’t allow pictures of their loved ones, and she had only childhood memories to rely on, which often failed her. If she brought up the subject of her mother to her father, there always had been a price to pay, so she’d stopped asking questions a long time ago.

“I believe remembering your mother will bring joy to your life. You hang on to your memories, little one.”

A fat tear forced its way from the corner of Beatrice’s eye. “Sometimes I can’t remember what her voice sounds like. Does that mean I don’t love her anymore?”

Sarah lifted the child into her arms and hugged her, rocking her like a baby. “Nee, Beatrice. Our human minds forget easily, but there will be times when you’ll hear someone speak and you’ll remember the sound of her voice and you’ll rejoice in that memory.”

Beatrice squeezed Sarah’s neck. “I like you, Sarah. You help me remember to smile.”

Sarah felt a grin playing on her own lips. Beatrice and Mercy had the same effect on her. They reminded her there was more to life than grief. She would always be grateful for her chance meeting with them, and Mose.

* * *

Bathed in the golden glow of the extra candle Beatrice had insisted on lighting before their supper meal, Mose noticed how different Sarah looked. Her hair had been neat and tidy under her stiff kapp earlier that morning, but now she looked mussed and fragile, as if her hair pins would fail her at any moment. He didn’t have to ask if the kinder had been a challenge. She wasn’t used to them around the house. He read the difficulty of her day in her pale face, too, and in the way she had avoided him the rest of the afternoon.

As if feeling his eyes on her, Sarah glanced up, a forkful of runner beans halfway to her mouth. Her smile was warm, but reserved. He needed to get her alone, tell her how much he appreciated her dealing with his daughters. He knew they were hard work. She deserved his gratitude. He’d worked hard on the barn teardown, endured the sun, but knew she’d worked harder.

“Beatrice tells me she had a lovely day.” He smiled at his daughter’s empty plate. It had been months since she’d eaten properly, and watching Beatrice gobble down her meal encouraged his heart.

Sarah and Beatrice exchanged a smile as if they had a secret all their own. “We spent the afternoon in the garden and drank lemonade with chunks of ice,” Sarah said. “I learned a great deal about Mercy from your helpful daughter. She knows when her baby sister is hungry and just how to place a cloth on her bottom so it doesn’t fall off. She’s a wealth of information, and I needed her help.” Sarah patted Beatrice’s hand.

The child smiled up at her. “I ate everything on my plate. Is there ice cream for dessert?”

Mose found himself smiling like a young fool. Seeing his daughters back to normal seemed a miracle.

Adolph banged his fork down and dusted food crumbs from his beard. “There will be no ice cream in this house tonight. Kinder should be seen but not heard at the table. There’ll be no reward for noise.” He glared at Sarah, as if she’d done something terrible by drawing the child out of her shell.

“My kinder are encouraged to speak, Adolph. Beatrice has always been very vocal, and I believe feeling safe to speak with one’s own parent an asset, not a detriment. I’m sure we can find another place to stay if their noise bothers you.”

“There is no need for you to leave. I’m sure I can tolerate Beatrice’s chatter for a few more days.” Adolph frowned Sarah’s way, his true feelings shown.

Mose fought back anger. He wondered what it must have been like to grow up with this tyrannical father lording over her.

As if to avoid the drama unfolding, Sarah pushed back in her chair and began to gather dishes.

“The meal was wunderbaar. You’re an amazing cook,” Mose said.

Sarah nodded her thanks, her eyes downcast, her hands busy with plates and glasses.

Beatrice grabbed her father’s hand and pulled. “Let’s go into the garden. I want to find the kitten.” She jumped up and down with excitement.

Adolph scowled at the child.

Mose scooped Mercy from her pallet of toys and left the room in silence, Beatrice skipping behind. Seconds later, the back door banged behind them.

Mose heard Adolph roar. “You see what you did? Can I never trust you to do anything right?” Adolph walked out of the kitchen, leaving Sarah alone with her own thoughts.

* * *

Moments later the sound of splashing water and laughter announced a water fight had broken out in the backyard. Sarah longed to join in on the fun, but instead went for a stack of bath towels and placed three on the stool next to the back door and a thick one on the floor. Mose would need them when their play finished.

She peeked out the window, amazed to see Mose Fischer soaked from head to toe, his blond hair plastered to his skull like a pale helmet. Beatrice had him pinned to the ground. Water from the old hose sprayed his face. She’d had no intention of watching their play but was glad she had. Mose’s patience with his daughter impressed her. Even young Mercy lay against her father’s legs as if to hold him down so Beatrice could have her fun with him.

Their natural joy brought Joseph to mind. He’d been playful and full of jokes at times. It had taken her a while to get used to his ways when they’d first married, and she’d known he’d found her lacking. She’d soon grown used to his spirit and had found herself waiting with anticipation for him to come in from the fields. She missed the joy they’d shared. A tear caught her unaware. She brushed the dampness away and sat in her favorite rocker. Minutes passed. She listened to the kinder’s laughter and then Mose’s firm voice reminding them it was time for bed.

The quilt she was stitching was forgotten as soon as the back door flew open and three wet bodies rushed in. She laughed aloud as she watched Mose try to keep a hand on Beatrice while toweling Mercy dry.

“Would you like some help?”

“I think Mercy is more seal than child.” He fought to hold on to her slippery body. Mercy was all smiles, her water-soaked diaper dripping on the kitchen floor.

Sarah rushed over and took the baby. The child trembled with cold and was quickly engulfed in a warm, fluffy towel. Sarah led the way to the indoor bathroom, baby in arms. Mose filled the tub with water already heated on the wood stove. Sarah added cold water, checked the temperature of the water, found it safe and sat Mercy down with a splash. Mercy gurgled in happiness as Sarah poured water over her shoulders and back.

“You’re a natural at this.” Mose spoke behind her.

Sarah reached around for Beatrice’s hand and the child jumped into the water with all the gusto of a happy fish. Water splashed and Sarah’s frock became wet from neck to hem. She found herself laughing with the kinder. Her murmurs of joy sounded foreign to her own ears. How long has it been since I giggled like this?

In the small confines of the bathroom, Sarah became aware of Mose standing over her. “I’m sure I can handle the bath. Why don’t you join my father for a chat while I get these lieblings ready for bed?”

Beatrice splashed more water. Mercy cried out and reached for Sarah. Grabbing a clean washcloth from the side of the tub, Sarah wiped water from the baby’s eyes. “You have to be careful, Beatrice.” She held on to the baby’s arm and turned to reach for a towel. Mose had left the room silently. She thought back to what she had said and hoped he hadn’t felt dismissed.

* * *

The girls finally asleep and her father in his room with the door closed, Sarah dried the last of the dishes and put them away. Looking for a cool breeze, she stepped out the back door and sat on the wooden steps. Her long, plain dress covered her legs to her ankles.

Fireflies flickered in the air, their tiny glow appearing and disappearing. She took in a long, relaxing breath and smelled honeysuckle on the breeze. Somewhere an insect began its lovesick song. Sarah lifted her voice in praise to the Lord, the old Amish song reminding her how much Gott once had loved her.

“Dein heilig statthond sie zerstort, dein Atler umbgegraben Darzu auch dein knecht ermadt...”

No one except Marta knew how much she’d hated Gott when Joseph had first died. She’d railed at Him, her loss too great to bear. But then she’d remembered the gas light in the barn and how she’d left it on for the old mother cat giving birth to fuzzy balls of damp fluff. She’d sealed Joseph’s fate by leaving that light burning. When she woke suddenly in the night, she’d heard her husband’s screams of agony as he tried to get out of the burning barn. Her own hands had been scorched as she’d fought to get to him. She hadn’t been able reach him and she’d given up. She’d failed him. He had died a horrible death. Her beloved Joseph had died, they’d said, of smoke inhalation, his body just bones and ashes inside his closed casket. She stopped singing and put her head down to weep.

“Something wrong, or are you just tired?” Mose spoke from a porch chair behind her.

With only the light coming through the kitchen window, Sarah turned. She strained to see Mose. “I’m sorry. I didn’t know you were there.” She wiped the tears off her face and moved to stand.

“Nee. Don’t go, please. I want to talk to you about Beatrice, if that’s all right.”

Sarah prepared herself for his disapproval. She’d heard it before from other men in the community when she’d broken Ordnung willfully. The Bishop especially seemed hard on her. She sat, waited.

Mose cleared his throat and began to talk. “I wanted to tell you how much I appreciate your taking such good care of my girls. They haven’t been this happy in a long time, not even with their grandmammi.”

Sarah touched the cross hanging under the scoop of her dress, the only thing she had left from her mother. If her father knew she had the chain and cross, he would destroy them. “I did nothing special, Mose. I treated the kinder like my mother treated me. Your girls are delightful, and I enjoy having them here. They make my life easier.” She clamped her mouth shut. She’d said too much. Plain people didn’t talk about their problems and she had to keep reminding herself to be silent about the pain.

“Well, I think it’s wunderbaar you were able to reach Beatrice. I’ve been very concerned about her, and now I can rest easy. She has someone to talk to who understands loss.”

Understands? Oh, I understand. The child hurt physically, as if someone had cut off an arm or leg and left her to die of pain. “I’m glad I was able to help.” She rose. “Now, I need to prepare for breakfast. Tomorrow is going to be a busy day for both of us. There is food to cook, a barn to haul away.”

“Wait, before you go. I have an important question to ask you.”

Sarah nodded her head and sat back down.

“I stayed up until late last night, thinking about your situation and mine. I prayed and prayed, and Gott kept pushing this thought at me.” He took a deep breath. “I wonder, would you consider becoming my frau?”

Sarah held up her hand as if to stop his words. “I...”

“Nee, wait. Before you speak, let me explain.” Mose took another deep breath and began. “I know you still love Joseph and probably always will, just as I still love my Greta. But I have kinder who need a mother to guide and love them. Now that Joseph’s gone and your daed insists the farm is to be sold, you’ll need a place to call home, people who care about you, a family. We can join forces and help each other.” He saw panic form in her eyes. “Wait. Let me finish, please. It would only be a marriage of convenience, with no strings attached. I would love you as a sister and you would be under my protection. The girls need a loving mother and you’ve already proven you can be that. What do you say, Sarah Nolt. Will you be my wife?”

Sarah sat silently in the chair, her face turned away. She turned back toward Mose and looked into his eyes. “You’d do this for me? But...you don’t know me.”

“I’d do this for us,” Mose corrected and smiled.

The tips of Sarah’s fingers nervously pleated and unpleated a scrap of her skirt. “We hardly know each other. You must realize I’ll never love you the way you deserve.”

“I know how much Joseph meant to you. He was like a bruder to me. You’d have to take second place in my heart, too. Greta will always be my one and only love.” Mose watched her nervous fingers work the material, knowing this conversation was causing her more stress. He waited.

She glanced at him. “I’d want the kinder to think we married for love. I hope they can grow to respect me as their parent. I know it won’t be the same deep love they had for their mamm. I’ll do everything I can to help them remember her.”

“I’m sure they’ll grow to love you. In fact, I think they already do.” Mose fumbled for words, feeling young and awkward, something he hadn’t felt in a very long time. He’d never thought he’d get married again, but Gott seemed to be in this and his kinder needed Sarah. She needed them. If she said no to his proposal he’d have to persuade her, but he had no idea how he’d manage it. She was proud and headstrong.

“What would people think? They will say I took advantage of your good nature.”

Mose smiled. “So, let them talk. They’d be wrong and we’d know it. I want this marriage for both of us, for the kinder. We can’t let others decide what is best for our lives. I believe this marriage is Gott’s plan for us.”

Sarah’s face cleared and she seemed to come to a decision. She smoothed out the fabric of her skirt and tidied her hair, then finally took Mose’s outstretched hand with a smile. “You’re right. This is our life. I accept your proposal, Mose Fischer. I will be your frau and your kinder’s mother.”

Sarah paused for a moment, then spoke. “Being your wife brings obligations. I expect you to honor my grief until such a time I can become your wife in both name and deed, as a good man deserves.” She looked him in the eye, seeking understanding. He deserved a woman’s love and she had none to give him right now.

Mose smiled and nodded, gave her a hand up and stepped back. “I wish there was something I could do to help you in your grief.”

Sarah didn’t know what to say. Few people had offered her a word of sympathy when she’d lost Joseph. They’d felt she’d caused his death. “I’m fine, really. I just need time.” She lied because if she said anything else, she would be crying in this stranger’s arms.

“Time does help, Sarah. Time and staying busy.”

She could feel his gaze on her. She hid every ache and hardened her heart. This was the Amish way. “Ya, time and work. Everyone tells me this.”

“Take your time, grieve.” He murmured the words soft and slow.

Her heart in shreds, she would not talk of grief with him, not with anyone. “I don’t want to talk anymore.” She moved past him and through the door, ignoring the throbbing veins at her temples. She would never get over this terrible loss deep in her heart. This unbearable pain was her punishment from Gott.

* * *

Mose wished he’d kept his mouth shut. He’d caused her more pain, reminding her of what she’d lost. Joseph had been a good man, full of life and fun. He’d loved Gott with all his heart and had dedicated himself to the Lord early in life. His baptism had been allowed early. Most Amish teens were forced to wait until they were sure of their dedication to Gott and their community, after their rumspringa, when they’re time to experience the Englisch world was over and decisions made, but not Joseph. Everyone had seen his love for Gott, his kindness, strength and purity. He felt the painful loss of Joseph. What must Sarah feel? Like Joseph, she seemed sure of herself, able to face any problem with strength...but there was something else. She carried a cloud of misery over her, which told him she suffered a great deal. What else could have happened to make her so miserable?

He heard a window open upstairs and movement, perhaps Sarah preparing for bed. Mose laughed quietly. Was he so desperate for a mother for his kinder that he had proposed marriage to a woman so in love with her dead husband she could hardly stand his touch? They both had to dig themselves out of their black holes of loss and begin life anew. Could marriage be the way? He knew he would never love again, yet his kinder needed a mother. Was he too selfish to provide one for them? Would marrying again be fair to any woman he found suitable to raise his kinder? No woman wanted a lovesick fool, such as he, on their arm. They wanted courtship, the normal affection of their husband, but he had none to give. He was an empty shell. Mose looked out over the tops of tall trees to the stars. Gott was somewhere watching, wondering why He’d made a fool like Mose Fischer. Stars twinkled and suddenly a shooting star flashed across the sky, its tail flashing bright before it disappeared into nothingness. It had burned out much like his heart.

Chapter Three (#ulink_a8e8d97a-d831-53d3-8e23-fde2dd7aa5bd)

Sarah’s eyes were red-rimmed and puffy. She placed her kapp just so and made sure its position was perfect, as if the starched white prayer kapp would make up for her tear-ravaged face.

“My mother wore a kapp like that, but it looked kind of different.” Beatrice clambered onto the dressing table’s stool next to Sarah.

“It probably was different, sweetheart. Lots of Amish communities wear different styles of kapps and practice different traditions.”

“How come girls wear them and not boys?” Beatrice reached out and touched the heavily starched material on Sarah’s head.

“Several places in the Bible tell women to cover their heads, so we wear the kapps and show Gott we listen to His directions.” Sarah wished she could pull off the cap, throw it to the ground and stomp on it. Covering her head didn’t make her a better person. Love did. And she loved this thin, love-starved child and her sweet baby sister. She felt such a strong need to make things easier for Beatrice and Mercy. “Would you like to help me make pancakes?”

As if on a spring, the child jumped off the stool and danced around the room, making Mercy laugh out loud and clap her hands. “Pancakes! My favoritest thing in the whole wide world.”

Sarah pushed a pin into her pulled-back hair and glanced at her appearance in the small hand mirror for a moment longer. She looked terrible and her stomach was upset, probably the result of such an emotional night. She’d lain awake for hours, unable to stop thinking about her promise to wed Mose. She’d listened to the kinder’s soft snores and movements, thinking about Joseph and their lost life together.

Gott had spoken loud and clear to her this morning. The depression and grief she suffered were eating up her life. She’d never have the love of her own kinder if she didn’t come out of this black mood and live again. But why would Mose want her as a wife, damaged as she was?

“Your eyes are red. Are you going to cry some more?” Beatrice jumped off the bench and danced around, her skirt whirling.

The child heard me crying last night. She forced herself to laugh and join in the child’s silly dancing. Hand in hand they whirled about, circling and circling until both were dizzy and fell to the floor, their laughter filling the room.

A loud knock came and her father opened the door wide. “What’s all this noise so early in the morning?”

Her joy died a quick death. “Beatrice and I were—”

“I see what you’re doing. Foolishness. You’re making this child act as foolish as you. It’s time for breakfast. Go to the kitchen and be prepared for at least twenty-five men to eat. We have more work to do now that the old barn is to be towed away. We’ll need nourishment for the hard day ahead.”

Beatrice snuggled close to Sarah, her arms tight around her neck. “This may be your home, but you’re out of line, Daed. Close the door behind you. We will be down when the kinder’s needs are met.” Sarah looked him hard in the eyes, her tone firm.

Her father’s angry glare left her filled with fury. She hated living at his farm, at his mercy. She longed to be in her own home two miles down the dusty road. She would not let him throw his bitterness the kinder’s way. She’d talk to him in private and make things very clear. She’d be liberated from his control once she and Mose were married. But, right now she was still a widow and had to listen to his demands. But not for long. Gott had provided her a way to get away from his control.

“Come darling, let’s get Mercy out of her cot and make those pancakes. We have a long day of cooking ahead of us and need some healthy food in our bellies.”

“Is that mean man your daed?” Beatrice asked.

Sarah helped her off the floor. “Ya.” She lifted Mercy from her cot and nuzzled her nose in the baby’s warm, sweet-smelling neck. She checked her diaper and found she needed changing. Mercy wiggled in her arms, a big grin pressing dimples in her cheeks. She held the warm baby close to her and thanked Gott her father’s harsh words hadn’t seemed to scare the baby.

Watching her sister get a fresh diaper, Beatrice spoke, “Why is he so angry? I don’t think he loves you.” Confusion clouded Beatrice’s face, a frown creasing her brow.

“Of course he loves me,” Sarah assured her. But as she finished changing Mercy’s diaper, she wondered. Does he love me?

* * *

The narrow tables lined up on the grass just outside Sarah’s kitchen door didn’t look long enough for twenty-five men, but she knew from experience they would suffice. She, Marta and three local women laughed and chatted as they covered the handmade tables with bright white sheets and put knives, forks and cloth napkins at just the right intervals.

As the men began gathering, Sarah placed heaping platters of her favorite breakfast dish made of sausage, potatoes, cheese, bread, onions and peppers in the middle of each table and at the ends. Bowls of fresh fruit, cut bite-size, added color to the meal. Heavy white plates, one for each worker, lined the tables. Glasses of cold milk sat next to each plate.

“The table looks very nice,” Marta whispered.

“It looks hospital sterile.” Sarah loved color. Bold, bright splashes of color. What would happen if she’d used the red table napkins she’d hemmed just after Joseph died? In her grief she’d had to do something outrageous, or scream in her misery. She longed to use the napkins for this occasion. Bright colors were considered a sin to Old Order Amish. How could Gott see color as a sin? Some of the limitations she lived under made no sense at all.

“We’re plain people, Sarah. Gott warned us against adorning ourselves and our lives with bright colors. They attract unwanted attention.” Marta straightened a white napkin and smiled at Sarah.

“I know what the Bishop says, Marta, but I think too many of our community rules are the Bishop’s rules and have nothing at all to do with what Gott wants. The older he gets, the more unbearable his ‘must not’s and should not’s’ get.”

“Everything looks good,” Marta said in a loud voice, drowning out Sarah’s last comment. Bishop Miller’s wife walked past and straightened several forks on the table close to Sarah.

Marta rushed back into the kitchen, her hand a stranglehold on Sarah’s wrist. “Do you think she heard you?”

“Who?”

“Bishop Miller’s wife.”

“I don’t care if she did.”

“Well, you should care. I know she’s a sweet old woman and always kind to me, but she tells her husband everything that goes on in the community, and you know it.”

Sarah shrugged and looked out the kitchen window, watching Mose approach the porch and settle in a chair too small for his big frame. Her future husband wore a pale blue shirt today, his blond hair damp from sweat and plastered down under his straw work hat. Beatrice left the small kinder’s table and crawled into her father’s lap, her arms sliding around the sweaty neck of his shirt.

“That child loves her daed.” Marta grabbed a pickle from one of the waiting plates of garnish.

“She does. It’s a shame she has nee mother to cuddle her.”

“I’m worried about you, Sarah. Lately all you do is daydream and mope.”

Sarah considered telling Marta her news but decided against it. Marta would never approve of a loveless marriage. “Don’t worry about me. I’ll be fine. I like having the kinder here. They’ve brightened my spirits. I’ve never had a chance to really get close to a child before. They can make my day better with just a laugh. They are really into climbing, even Mercy. This morning I caught her throwing her leg over her cot rail. She could have fallen if I hadn’t been close enough to catch her. I’m going to see if someone has a bigger bed for her today. She’s way too active to manage in that small bed Daed found in the attic.”

Sarah grabbed two pitchers of cold milk and headed out the back door.

“Is there more food? These men are hungry.” Adolph grabbed Sarah by the arm as she passed through the door, his fingers pinching into her flesh.

“Ya, of course. I’ll bring out more.” She placed the pitchers on the table and returned the friendly smile Mose directed her way.

“See that you do,” her father barked, as if he were talking to a child. He moved down the table, greeting each worker with a handshake and friendly smile.

Sarah hurried into the kitchen and grabbed a plate of hot pancakes from the oven and rushed back out the kitchen door, a big jar of fresh, warmed maple syrup tucked under her arm. Her father was right about one thing. The men were eating like an army.

* * *

The last of the horse-drawn wagons carrying burned wood pulled out of the yard and down the lane, heading for the dump just outside town.

Mose grabbed the end of a twelve-foot board, pulled it over and nailed it into the growing frame with three strong swings of the hammer. A brisk breeze lifted the straw hat he wore, almost blowing it off his head. He smashed it down on his riot of curls and went back to work. The breeze was welcome on the unseasonably hot morning.

“Won’t be much longer now,” the man working next to Mose muttered. The board the man added would finish the last of the barn’s frame, and then the hard work of lifting the frames would begin.

Sweat-soaked and hungry, Mose glanced at the noon meal being served up a few yards away and saw Sarah carrying a plate piled high with potato pancakes. She’d been in and out of the house all morning, her face flushed from the heat of the kitchen. Beatrice trailed behind her, a skip in her steps and the small bowl of some type of chow-chow relish dripping yellow liquid down the front of her apron as she bounced.

He laughed to himself, taking pleasure in seeing Beatrice so content. Sarah had a natural way with kinder. She’d make a fine mother.

“Someone needs to deal with that woman.”

“Who?” Mose turned his head, surprised at the comment. He looked at the man who’d spoken and frowned. Standing with his hands on his hips, the man’s expression dug deep caverns into his face, giving Mose the impression of intense anger.

“The Widow Nolt, naturally. Who else? Everyone knows she killed Joseph with her neglect. Bishop Miller might as well shun her now and get it over with. No one wants her in the community anymore. She causes trouble and doesn’t know when to keep her mouth shut.”

Mose mopped at the sweat on his forehead. “What do you mean, she killed Joseph? There’s no way she’s capable of doing something like that. The police said he died of smoke inhalation.”

Stretching out his back and twisting, the man worked out the kinks from his tall frame, his eyes still on Sarah. “She did it, all right, bruder. She left the light on in the barn, knowing gas lights get hot and cause fires.”

“I’m sure she just forgot to turn it off. People forget, you know.” Mose knew he was wasting his breath. Some liked to think the worst of people, especially people like Sarah, who were powerless to defend themselves.

“Sarah Nolt is that kind of woman. Her own father says she’s always been careless, even as a child.”

“I believe Gott would have us pray for our sister, not slander her for something that took her husband’s life.”

“Well, you can stand up for her if you like, but I’m not. She’s a bad woman, and I wouldn’t be here today if it weren’t for my respect for Joseph. He was a good man.”

“He’d want you to help Sarah, not slander her.” Mose threw down the hammer. His temper would always be a fault he’d have to deal with, and right now he’d best move away or he’d end up punching a man in the mouth.

The food bell rang out. He dusted as much of the sawdust off his clothes as he could. Still angry, he moved toward the long table set up in the grass and took the seat closest to the door. A tall glass of cold water was placed in front of him by a young girl. “Danke.” He downed the whole glass.

“You’re welkom,” the girl muttered and refilled his glass. Mose watched Sarah as she served the men around him. She acted polite and kind to everyone, but not one man spoke to her. The women seemed friendlier but still somewhat distant. He saw her smile once or twice before he dug into his plate of tender roast beef, stuffed cabbage rolls and Dutch green beans. Sarah knew her way around a kitchen. The food he ate was hardy and spiced to perfection.

A group of men seated around the Bishop began to mutter. A loud argument broke out and Mose could hear Sarah’s name being bandied about. Marta hurried past, her face flushed, and the promise of tears glistening in her eyes. Her small-framed shoulders drooped as she made her way into the house. Soon Sarah was out the door, her eyes locked on Bishop Miller who sat a few seats from Mose.

“You have much to say about me today, Bishop Miller. Would you like to say the words to my face?” Her small hands were fisted, her back straight and strong as she glared at the community leader.

Adolph shoved back his chair and stood.

“Shut your mouth, Sarah Yoder. I will not have you speak to the Bishop like this. You are out of line. You will speak to him with respect.”

“My name is Nolt, Daed. No longer Yoder. And I will not be told to hush like some young bensel. If the Bishop has something to say, he need only open his mouth or call one of his meetings.”

Mose rose. Gott, hold Sarah’s tongue. She had already dug a deep well of trouble with her words. Her actions were unwise, but he would not stand by and watch her be pulled down further by her father’s lack of protection. Let the Bishop show proof of her actions and present them in a proper setting if he had issues with her.

Bishop Miller’s wife hurried to Sarah and put her arms around her trembling body. “Let us leave all this for today and have cold tea in the kitchen. We’re all tired and nerves frayed. Today a barn goes up. It is a happy day, Sarah. One full of promise. Let us celebrate and not speak words that cannot be taken back.”

Mose waited, wondering if Sarah would relent. She turned and stared deep into the eyes of the woman next to her. Moments passed and then she crumbled, tears running down her face as she was escorted away.

Mose watched the door shut behind the women. He longed to know if Sarah was all right but knew she wouldn’t want him interfering. “What’s going on?” Mose murmured to Eric, Sarah’s brother.

“Someone has found proof that Sarah was the one who gave money to Lukas, a young teenager who recently ran away from the community.”

“Money? Why would she do that?” They spoke in whispers, his food forgotten.

“I only heard a moment of conversation but it seems Daed saw her speaking with the boy’s younger brother the day before Lukas took him and left for places unknown.”

“That’s not solid proof. Sarah must be given a chance to redeem herself.”

“She’ll get her chance. A meeting has been called, and I plan to talk to Bishop Miller before it comes around. I suspect she’ll be shunned, but I have to make an effort to calm the waters. Lord alone knows what would happen to her if she’s forced to live amongst the Englisch.” Eric got up to leave, but turned back to Mose. “Marta’s offered to look after the kinder at our house until tomorrow. Sarah is too upset to think clearly. ”

* * *

Tired from the long day of cooking and cleaning, Sarah lay across her childhood bed on the second floor of her father’s house, her pillow wet from tears. She cried for Joseph, for the life she’d lost with him, and for the loneliness she’d felt every day since he’d died. She needed Joseph and he was gone forever.

Marta held her hand in a firm grip. “You mustn’t fret so, Sarah. The children can stay with Eric and me tonight. Most likely you will be given a talking to tomorrow and nothing more.”

“And if I’m shunned, what then? You and Eric won’t be allowed to talk to me. The whole community will say I’m dead to them. Who will I call family?”

“Why did you give Lukas money? You knew you ran the risk of being found out.”

Sarah sat up, tucking her dress under her legs. Marta handed her a clean white handkerchief and watched as Sarah wiped the tears off her face. “I couldn’t take it anymore. Every day I heard the abuse. Every day I heard the boys crying out in pain.”

“Did you talk to any of the elders about this?”

“I talked to them but they put me off, said I was a woman and didn’t understand the role a father played in a boy’s life.” Sarah blew her nose and tried to regain control of the tremors that shook her body.

“But surely beating a young boy senseless is not in Gott’s plan. Do you believe your daed would tell on you if he knew it was you who gave the boys money?”

“Of course he would, but he didn’t know. I made sure he was gone the day I slipped money to Lukas.”

“Then how?”

Sarah smoothed the wrinkles out of her quilt and set the bed back in order. “It doesn’t matter now.”

“How would you survive among the Englisch? You know nothing about them. Your whole life has been Amish. I fear for you, Sarah.” Marta brushed away her tears as they continued to fall.

A shiver ran through Sarah as she thought about what Marta said. She wouldn’t be strong enough to endure the radical changes that would have faced her. Thank Gott for Mose’s offer of marriage, for the opportunity to go to Sarasota and leave all this behind. But would he want to marry her if she was shunned and was she prepared for a loveless marriage? She feared not. Gott’s will. Grab hold of Gott’s will.

Chapter Four (#ulink_01b009e4-ce77-56dc-9f68-da2a09786b6b)

Sarah roamed through the small farmhouse, gathering memories of Joseph and their time together. She had no picture to keep him alive in her mind, only objects she could touch to feel closer to him.

A sleepless night at her father’s farm, after her confrontation with the bishop, had left her depressed and bone tired.

Downstairs, she smiled as she picked up a shiny black vase from the kitchen window. When Joseph had bought it that early spring morning, he’d known he’d broken one of the Old Order Amish Ordnung laws laid down by Bishop Miller. The vase was a token of Joseph’s love. It was to hold the wildflowers they gathered on their long walks in the meadows. The day he’d surprised her with the vase she’d cried for joy. Now it felt cold and empty like her broken heart. The vase was the only real decoration in the farmhouse, as was custom, but their wedding quilt, traditionally made in honor of their wedding by the community’s sewing circle, hung on the wall in the great room.

In front of the wide kitchen windows, she fingered the vase’s smooth surface, remembering precious moments. Their wedding, days of visiting family and friends, the first time she’d been allowed to see the farmhouse he’d built with other men from the area. He’d laughed at her as she’d squealed with delight. The simple, white two-story house was to be their home for the rest of their lives. He’d gently kissed her and whispered, “I love you.”

Moved to tears, her vision blurred. She stumbled to the stairs and climbed them one by one, her head swimming with momentary dizziness. On the landing she caught her breath before walking into their neat, tiny bedroom. Moments later she found the shirt she’d made for Joseph to wear on their wedding day hanging in the closet next to several work shirts and two of her own plain dresses.

Sarah tucked the blue shirt on top of a pile of notes and papers she’d put in the brown valise just after he’d died. He used the heavy case when he’d taken short trips to the Ohio Valley area communities to discuss the drought. In a few days she’d use it to pack and leave this beloved farmhouse forever.

Her dresses and his old King James Bible, along with the last order for hayseeds written in his bold print, went into the case. The Book of Psalms she’d given him at Christmas slipped into her apron pocket with ease. Her memories of him would be locked away in this heavy case, the key stashed somewhere safe.

Most of her other clothes and belongings would be left. She’d have no need for them now. Mose would take care of her. A fresh wave of anxiety flushed through her. She had no idea if she could go through with this marriage.

She thought back to Joseph and wondered what he’d think of the drama surrounding her. He’d be disappointed. He’d followed the tenets of the Old Order church faithfully. The rules of the community were a way of life he’d gladly accepted. Yes, he’d be disappointed in her.

She faced shunning. Bishop Miller preached that those who were shunned or left the faith would go to hell. Joseph was with the Lord. I’d never see my husband again.

A wave of dizziness caught her unaware and she grabbed the bed’s railings to steady herself. Moments later, disoriented and sick to her stomach, she sat on the edge of the bed and waited for the world to stop spinning. All the stress had frayed her nerves and made her ill.

A loud knock came from downstairs. Sarah froze. She didn’t want to talk to anyone, not even Marta, but knew she’d have to see her before she left. There were others in the community she’d miss, too. Her distant family members, her old schoolteacher, the friendly Englisch woman at the sewing store...all the people who meant everything to her. They’d wonder what really had happened, why she suddenly had disappeared, but she knew someone would tell them what she’d done. Her head dropped. A wave of nausea rolled her stomach, twisting it in knots.

The knock became louder, more insistent. She moved to the bedroom window. No buggy was parked out front. Perhaps one of the neighborhood kinder was playing a joke on her. She checked the front steps and saw the broad frame of a man. Had her father come to give her one last stab to the heart? It would be just like him to come and taunt her about her coming marriage to Mose.

“Sarah? Are you there? Please let me in.”

Mose’s voice called from her doorstep. He sounded concerned, perhaps even alarmed. Had something happened to one of the kinder? Why would he seek her out? He’d heard it all. He was an elder in his community. Even if he wasn’t Old Order Amish and didn’t live as strict a life as she did, but he’d be angry she’d given the boys money and would judge her. Still, he was a good man, a kind man. Perhaps he just wanted to talk to her.

The thought of his kindness had her rushing down the stairs and opening the heavy wood door Joseph had made with his own hands. She used the door as a shield, opening it just a crack. “Ya?” She could see a slice of him, his hair wind-blown, blue eyes searching her face.

“Hello, Sarah. I thought I might find you here.”

She nodded her head in greeting.

“Are you all right?” Mose’s hand rested on the doorjamb, as if he expected to be let into the house.

Sarah held the door firm. “I’m fine. What do you want, Mose? I have things to do. I’m very busy.”

“I’m worried about you. You’ve been through so much.”

“And none of it is your business,” Sarah snapped, instantly wishing she could take back her bitter words. He’d done nothing but be kind to her. She missed the girls and wondered how they were, if Marta was still caring for them. She pushed strands of hair out of her eyes and searched his expression. She saw no signs of judgment.

“You’re right. All this is none of my business, but I am soon to be your husband. I want to help, if I can. Please, can I come in for a moment?”

On trembling legs, she stepped back to open the door all the way. “Come in.”