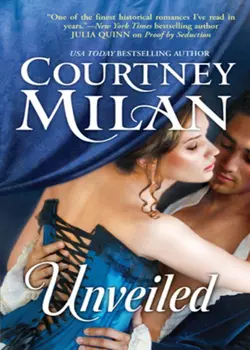

Unveiled

Courtney Milan

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 150.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Ash Turner has waited a lifetime to seek revenge on the man who ruined his family – and now the time for justice has arrived.At Parford Manor, he intends to take his place as the rightful heir to the dukedom and settle an old score with the current duke once and for all. But instead he finds himself drawn to a tempting beauty who has the power to undo all his dreams of vengeance. Lady Margaret knows she should despise the man who′s stolen her fortune and her father′s legacy – the man she′s been ordered to spy on in the guise of a nurse.Yet the more she learns about the new duke, the less she can resist his smoldering appeal. Soon Margaret and Ash find themselves torn between old loyalties – and the tantalizing promise of passion.