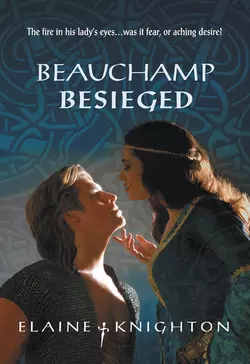

Beauchamp Besieged

Elaine Knighton

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.86 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Twas Madness!The blood of her people stained his hands, yet Ceridwen ap Morgan ached for his touch. Though Lord Raymond Beauchamp sparked fear throughout the Marches, her woman′s heart knew that this dragon of a man nursed secret wounds in his soul. And she must wed this enigma. She shuddered–but was it from darkest dread…or deepest desire?Treaties Be Hanged!Raymond Beauchamp saw no advantage in wedding Ceridwen. Her very presence raised unwelcome ghosts of memory, and marriage to anyone would only interfere with older, darker vows he′d made. Yet he feared ′twas already too late! For his blood, once hot for revenge against his barbaric brother, now burned only for her…!