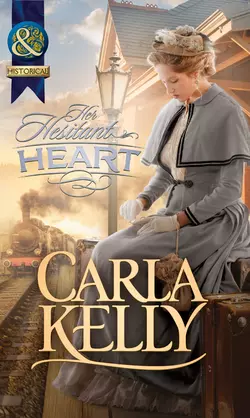

Her Hesitant Heart

Carla Kelly

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ON THE FRONTIER OF A NEW LIFE… Tired and hungry after two days of travelling, Susanna Hopkins is just about at the end of her tether when her train finally arrives in Cheyenne. She’s bound for a new life in a Western garrison town. Then she discovers she doesn’t even have enough money to pay for the stagecoach!Luckily for her the compassionate Major Joseph Randolph is heading in the same direction. As a military surgeon, Joe is used to keeping his professional distance. But despite Susanna’s understated beauty he’s drawn to this woman who carries loss and pain equal to his own and has a heart which is just as hesitant and wary…‘Always original, always superb, Ms Kelly’s body of work is a timeless delight.’ – RT Book Reviews