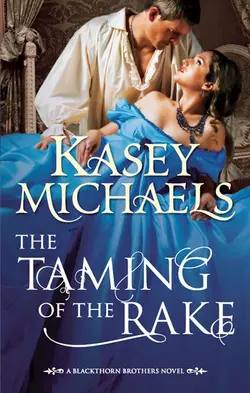

The Taming of the Rake

Kasey Michaels

Meet the Blackthorn Brothers – three unrepentant scoundrels infamous for being perilous to love… Charming, wealthy and wickedly handsome, Oliver ‘Beau’ Blackthorn has it all… except revenge on the enemy he can't forget. Now the opportunity for retribution has fallen into his hands.But his success hinges on Lady Chelsea Mills-Beckman – the one woman with the power to distract him from his quest. Desperate to escape her family's control, Lady Chelsea seizes the chance to run off with the notorious eldest Blackthorn brother, knowing she's only a pawn in his game.But as Beau draws her deep into a world of intrigue, danger and explosive passion, does she dare hope he'll choose love over vengeance?

Praise for USA TODAY bestselling author

KASEY

MICHAELS

“Kasey Michaels aims for the heart and never misses.”

—New York Times bestselling author Nora Roberts

“A poignant and highly satisfying read … filled with simmering sensuality, subtle touches of repartee, a hero out for revenge and a heroine ripe for adventure. You’ll enjoy the ride.”

—RT Book Reviews on How to Tame a Lady

“Michaels’s new Regency miniseries is a joy … You will laugh and even shed a tear over this touching romance.”

—RT Book Reviews on How to Tempt a Duke

“Michaels has done it again … Witty dialogue peppers a plot full of delectable details exposing the foibles and follies of the age.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review, on The Butler Did It

“Michaels demonstrates her flair for creating likeable protagonists who possess chemistry, charm and a penchant for getting into trouble. In addition, her dialogue and descriptions are full of humour.”

—Publishers Weekly on This Must Be Love

“Michaels can write everything from a light-hearted romp to a far more serious-themed romance. [She] has outdone herself.”

—RT Book Reviews on A Gentleman By Any Other Name (Top Pick)

“[A] hilarious spoof of society wedding rituals wrapped around a sensual romance filled with crackling dialogue reminiscent of The Philadelphia Story.” —Publishers Weekly on Everything’s Coming Up Rosie

Dear Reader,

In the more than thirty years I’ve been spinning stories, and with the more than one hundred heroes I’ve created, I’ve written about a few who have not qualified as “angels.” But none of them were bastards. Well, at least not according to the legal definition.

Then I had this idea about three bastard sons of an English marquess and an actress mother. Loved by their father, educated “above their station,” rigged out, with scads of money in their pockets and, of course, handsome as sin. Where do they fit in an age and a society that stakes so much on pristine lineage? Certainly no papa would hand his daughter over to a bastard, no matter how wealthy or civilised that suitor might be. No, the bastard would be relegated to the very fringes of society, caught between two worlds, belonging to neither.

Well, that couldn’t happen, not in my world! Love simply has to conquer all! But it would take three very special young ladies to defy convention and their families, and sacrifice their own place in society, all for the love of a brash, or a fun-loving, or a brooding and secretive Blackthorn brother.

Come along, meet Beau Blackthorn and the woman who will risk everything—not to defy her brother as she thought, but for the love of a most unacceptable yet irresistible man. Then, please, watch for A Midsummer Night’s Sin and Much Ado About Rogues, coming soon. The Blackthorn Brothers. You’re going to love them!

Happy reading,

Kasey Michaels

The

Taming

of The Rake

Kasey Michaels

The Blackthorn Brother

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

To my daughters and best friends, Anne and Megan, with love

PROLOGUE

“Men have died from time to time,

and worms have eaten them, but not for love.”

—As You Like It, William Shakespeare

OLIVER LE BEAU BLACKTHORN was young and in love, which made him a candidate for less than intelligent behavior on two counts.

And so it was that, with the clouded vision of a man besotted, that same Oliver Le Beau Blackthorn, raised to think quite highly of himself, the equal to all men, did, with hat figuratively in hand, hope in his heart and a bunch of posies clutched to his breast, bound up the marble steps to the mansion in Portland Place one fine spring morning and smartly rap the massive door with the lion’s head brass knocker.

Oliver, known to his family as Beau, performed a quick mental inventory of his appearance, one he’d worked over for a full two hours, crumpling both a half dozen neck cloths and his valet’s abused nerves in the process.

He was presenting himself in a morning rigout of finest tan buckskins, dazzlingly white linen, a stunning yet unobtrusive waistcoat of marvelously brushed silk shot through with cleverly designed stripes made of the lightest tan thread and a darkest blue jacket that so closely followed the lines of his young, leanly muscled body that he could not manage to get his arms in or out of the sleeves without assistance.

He’d practiced the jaunty positioning of his curly brimmed beaver in front of the pier glass in his dressing room for a full ten minutes before pronouncing the angle satisfactory; showing off his thick crop of sun-streaked blond hair rather than crushing it, providing just enough cover from the brim that his bright blue eyes were not cast into the shade.

It only just now occurred to him that the hat would be handed over to the Brean footman, along with his new tan kid gloves and walking stick, and Lady Madelyn would never see them.

Hmm, no one had as yet answered his knock. Shabby, that’s what that was. He lifted his hand to the knocker once more, just as the door opened, and very nearly tapped on the footman’s nose.

Beau glared at the fellow, who stepped back quickly, and the well-tailored Mr. Blackthorn sauntered into the black-and-white marble-tiled foyer, feeling his cheeks growing hot and damning his lifelong tendency to blush.

Shortly thereafter he was admitted to the Grand Drawing Room by the family butler, who seemed disapproving in some way as he looked at the flowers, to await the appearance of Lady Madelyn Mills-Beckman, elder daughter of the Earl of Brean, and Beau Blackthorn’s beloved.

“Quite a lot of Bs in there,” he murmured to himself, an outward sign of the nervousness he felt but had thus far managed to conceal. There had been that small slip with the footman, but by and large, Beau was still feeling quite confident.

Or he was until a young female voice interrupted his thoughts.

“Talking to oneself is considered by some to be an indication of madness. At least that’s what Mama said once about Aunt Harriet, and she was mad as a hatter. Aunt Harriet, that is. Mama was simply silly. I once saw Aunt Harriet with her clothes on backward. Are those flowers for Madelyn? Should I tell you that she loathes flowers? They make her sneeze, and her eyes water, and then her nose begins to drip …”

Beau had already turned about smartly, to see Lady Chelsea Mills-Beckman, a rather pernicious brat of no more than fourteen, ensconced on a flowered chaise near the window. She had her bent legs tucked up under the skirts of her sprigged muslin gown, and an open book was perched on her lap.

His reluctant scrutiny took in her long and messily wavy blond hair that had half escaped its ribbon, the eyes that were neither gray nor quite blue below flyaway eyebrows that could make her look devilish and pixyish at the same time, the budding young body that should certainly be positioned with more circumspection.

The wide, teasing grin on her face, he ignored.

Beau had suffered the misfortune of Lady Chelsea’s presence twice before in the past month, always with a book in her hand and a too-smart tongue in her head, and he was as loath to see her this morning as he’d been either of those other times.

“Your father should order a lock put on the nursery door,” he drawled now, even as he strode to the French doors and unceremoniously tossed the posies out into the garden.

Lady Chelsea laughed at this obvious silliness, be it directed at his statement or the flowers he couldn’t be certain. But then she told him, drat her anyway.

“I’d only find another way out. I’m motherless, you understand, and allowances must be made for me. Too young for a Come-out, too prone to mischief to be left with my governess in the country while Madelyn is being popped off. I suppose you want me to vacate the room now, before Madelyn makes her grand entrance and you delight her by drooling all over her shoe tops. Oh, look at that, you’ve got a wet spot from the stems on that odiously homely waistcoat. I’ll wager that’s put a crimp in your airs of consequence.”

Beau hastily brushed at his waistcoat before his brain could inform his pride that the blasted girl was making a May game out of him. Had he really only considered the nursery for her banishment? He would rather the cheeky child left the continent, perhaps even the universe, but refrained from that particular honesty. “I would like to converse with Lady Madelyn in private, yes.”

“Oh, very well, if you’re going to be all starchy about the thing.” Lady Chelsea got to her feet and smoothed down her gown. She was a rather attractive child, he supposed. She’d probably break a dozen hearts in a few years. But she didn’t hold a patch on her sister, she of the ice-blue eyes and nearly white-blond hair, her mouth a pouty pink, her skin so creamy and flawless above the low bodice of her gowns.

Beau inserted a finger beneath his collar and gave a small tug, as it had suddenly become difficult to swallow. That action then turned impossible as the object of his affection entered the room.

“Mr. Blackthorn, what a lovely surprise. I hadn’t thought to see you so soon after our dance at Lady Cowper’s ball. Naughty man, showing up uninvited as you did. Quite shocking, really. And just to dance with me and then take your leave? It was all quite romantic and daring.” Lady Madelyn tipped her head to one side as if trying to somehow see behind his back. “Did you bring me a gift? I adore gifts.”

Beau bowed to the love of his life and apologized for his sad lack of manners.

Lady Madelyn looked crestfallen for a moment but then brightened. “Very well, I accept your apology. Next time, perhaps you’ll bring me flowers. I do love flowers.”

A giggle from the corner alerted Beau to the fact that the brat was enjoying another small joke at his expense, but he refused to look at her or acknowledge the hit. “I will buy you an entire hothouse full of flowers,” he promised Lady Madelyn earnestly, bowing yet again. “And now, if I might have a word with you in private? There is something of great personal importance I wish to ask you. After the events of last night, I should think you know what that is.”

She didn’t move, didn’t blink, and yet something changed in Lady Madelyn’s ice-blue eyes. Her smile became frozen in place, and her creamy-white skin seemed to pale even more, all the way to porcelain, and looked just as cold and hard.

“Now, Mr. Blackthorn, you know that is quite impossible. No young lady of quality is ever without a chaperone in the presence of a gentleman, as we both know. I do believe, if I am interpreting your statement correctly, that it is my absent father you should be asking for, not me,” she scolded in a rather strangled tone. “Chelsea, would you be a dear and ask our brother to step in here for a moment? Mrs. Wickham is still dressing, I’m afraid.”

“But I saw her earlier on the stairs, and she was completely—”

Lady Madelyn whirled about to glare at her sister. “Do as I say!”

“You’re such a snob,” Chelsea said as she flounced out of the room.

Oliver Le Beau Blackthorn was young and in love, and like many of his similarly afflicted brethren, not thinking too clearly. But it didn’t take a clear thinker to recognize that the rosy scenario he’d pictured in his brain and the scene playing out in front of him now were poles apart.

She was probably nervous. Women tended to be nervous at times like these; they couldn’t seem to help themselves. He’d make allowances.

“Lady Madelyn … and if I might be so bold, dear, dear Madelyn,” he said, taking quick advantage while they were still alone, dropping to one knee in front of her and clasping her right hand in his, just as he had practiced the move on Sidney, his horribly embarrassed valet. “It can be no secret that I have admired you greatly since the moment we first met. With each new meeting my affection has grown, and I believe it has been reciprocated, most especially after our walk together the other evening when I so dared as to kiss you and you did me the great honor of allowing me to—”

“Not another word! How provokingly common of you to speak of such things! No gentleman would ever be so crass as to throw a moment’s folly into a lady’s face. A single kiss? It was a lark, a dare, no more than that. Get up! You’re a dreadful creature.”

A single kiss? It had been considerably more than a single kiss. She’d allowed him to cup her breast through the thin fabric of her gown, moaned delightfully against his mouth as he’d run his thumb across her hard, pert nipple. If not for the sound of approaching footsteps, there would have been much more. He’d nearly been bursting, had come within moments of thoroughly embarrassing himself, for God’s sake.

He would have thought her a cold, heartless tease if he’d been in his right mind. But no, he was in love. And she was clearly upset.

“I know I’m being forward,” Beau persisted—he’d been up all night rehearsing this speech. “I ask only that I have your permission to address your father. I would not wish to do so if my affection truly wasn’t returned.”

“Well, it isn’t,” Lady Madelyn responded hotly, pulling her hand free. “You overreaching nobody. Just because your father is one of us, and you’ve been accepted in some quarters because of him and because of that ridiculous fortune he’s bestowed on you, doesn’t mean you’ll truly ever be one of us. Don’t you even know when someone is making a May game of you? You’re a joke, Beau Blackthorn, a laughingstock to everyone in Mayfair, and you’re the only one who doesn’t know it. As if I or any female of decency in the ton would deign to align herself with a—a bastard like you.”

Beau would later remember that the lady’s brother entered the drawing room at some point during this heart-shredding declaration, along with two burly footmen who quickly grabbed hold of Beau’s arms and hauled him to his feet and beyond, so that he was dangling between them, his boots a good two inches off the floor.

He called out his beloved’s name, but she had already turned her back and was walking away from him, holding up the hem of her skirts as if to avoid stepping in something vile.

A dare? A joke? That’s all he’d been? She—and God only knew who else—had been encouraging him, yet secretly laughing at him? Is that how Society really saw him? As some sort of monkey they could watch dance? A performing bear they could prod with a stick, just to see how he’d react? Here, bastard, kiss me, touch what you’ll never have. And then go away. You’re not one of us.

His mother had warned him, warned all three of her sons. Beau had never believed the dire predictions that she ascribed to the ridiculous notions and actions of their father. The world had to have been better than she’d painted it. But she’d been right, and he and his father had been wrong.

At last Beau, his dreams, all of the assumptions and hopes of his young life shattering at his feet, came to his senses. He struggled violently to be free, to no avail, until he was carried out the way he had come in and been thrown down the marble steps to the flagway. He could hear as well as feel the crack of a bone in his left forearm as it made sharp contact with the edge of one of the steps even as all the air left his lungs in a painful whoosh.

Then the first snap of the whip hit him across his back, and he could do nothing more than curl himself into a ball and take each blow, trying to protect his face, his eyes, his injured arm.

“Insult my sister, will you? Take advantage of her innocence?” The viscount flourished the coach whip again and again, the braided leather with the hard, metal tip slicing Beau’s new morning coat straight on through to his skin, setting his back on fire. “Putting on airs above your station? That’s what coddling your type leads to, damn it. Society in shambles! The very breath you take is an abomination to all that is decent. I should have you bound and tossed in the Thames like the worthless dog you are!”

At last the assault with the whip ended, followed briefly by some well-placed kicks from the footmen, and Beau heard the slam of a door. He tentatively got to his feet, his body a mass of pain, his heart and soul in tatters, just like his fine coat. One of the footmen spat at him before they both shouted at him to go away, their coarse oaths drawing the attention of any passersby who hadn’t already stopped to stare at the spectacle.

Still crouching like a whipped dog as he supported his broken arm, Beau turned to look back at the mansion, only to have the door open slightly and the face of Lady Chelsea peek out at him, her eyes awash in tears.

“I’m so, so sorry, Mr. Blackthorn,” she said, sniffling, tears running down her cheeks. “Madelyn is vain and heartless, and Thomas is just an ass. They can neither of them help themselves, I suppose. I don’t think you a joke. I … I think you’re entirely worthy, if a little silly in your head. But perhaps you should go away now. Very far away.”

And then she closed the door, and Beau was left to stare down his own groom, who had been waiting with the new curricle that had also been purchased to impress Lady Madelyn. He’d planned to take her for a drive, once he’d spoken to her father, and perhaps steal another kiss—and more—as they rode out to Richmond Park.

“Thank you, no, and thank you so much for springing to my aid with all the loyalty of a potted plant,” Beau said stiffly, gritting his teeth against the nausea that threatened as the groom stepped forward to lend him support. “Return that damned thing to my stables. I’ll walk back to Grosvenor Square.”

And that’s just what Beau did. He walked all the long blocks to his father’s mansion. Staggered at times but always righted himself, kept his chin high, his spine straight, looking each passerby in the eye. Let them see, let them all see what they’d done to him while calling themselves gentlemen and ladies, thinking themselves somehow better than he, more civilized. Let them laugh now if they could. And let them remember, so that the next time they saw Oliver Le Beau Blackthorn or crossed his path, they’d know well enough to beware.

With each step, as those he encountered quickly crossed the street to avoid the torn and bloody sight of him, while none of them, acquaintance or supposed friend, raised a hand to help him, that same Oliver Le Beau Blackthorn left more of his youth behind him, until he was left with only one thought, one remaining truth.

His money, his looks, his charm, the friendships he’d believed he’d forged at school and here in London, the acceptance he’d thought he’d found? At the end of the day, they meant nothing.

He’d been a fool, he knew that now. Young and prideful and stupid. The laughingstock Lady Madelyn had called him.

The oldest son of the Marquess of Blackthorn, at two and twenty years of age, had at last seem himself as the world saw him. Not as a man, not as a friend, not as a mate. They saw him as he was. Illegitimate. Born on the wrong side of the blanket, son of a marquess and a common actress. An educated and well-heeled bastard, yes, but a bastard all the same.

He walked on, his heart hardening, his mind holding on to one thought, the only thought that kept him from giving in to his pain, pitching forward once more into the gutter.

He would do as the brat advised. He would go away. Far away.

But he would return.

Someday.

And when he did, by God, let any man dare to laugh at him again!

CHAPTER ONE

LADY CHELSEA MILLS- BECKMAN, always the epitome of grace and charm, launched the thick marble-backed book of sermons directly at the head of her brother, Thomas, as of the past two years the seventeenth Earl of Brean.

Her aim was woefully off, and the tome missed him completely, which did nothing to improve her mood.

His lordship bent down to retrieve the book, inspecting the spine for any hint of damage before closing it and setting it on his desk. He was a man in his early forties, too well fed, and with a pink complexion that always seemed to border on the shiny. He thought himself handsome and brilliant, but was neither. He more closely resembled, Chelsea believed, an expensively dressed pig.

“God’s words, Chelsea, delivered through the holy Reverend Francis Flotley himself. ‘A woman’s role is to obey, and her greatest gift her compliance with the superior wisdom of men. Let her gently be led in her inferior intellect, like the sheep in the field, or else otherwise lose her way and be branded morally bereft, a harlot in heart and soul, and worthy only of the staff.’”

The siblings had been closeted in the study in Portland Place for little more than a quarter-hour on this fine late April morning, and yet this was already the fourth time her brother had quoted from the book of sermons. Which, clearly, had been at least one time too many, as it had prompted the aforementioned action of her ladyship wrenching the book from his hand and sending it winging at him.

“Herd us poor, silly, brainless women, lead us gently by the hand as long as we obey, and beat us with the staff if we refuse to behave like sheep. That’s what that means. What a pitiful mouthful of claptrap,” Chelsea countered, attempting to control her breathing in her agitation. “You’re a parrot, Thomas, mouthing words you’ve learned but haven’t taken the time to understand. And did you ever notice, brother mine, that all of this nonsense is always penned by men? Is that what’s next for me? You’re going to beat me? As I recall the thing, you were once rather proficient with the whip, and not averse to employing it on someone who could not defend himself.”

The earl quickly rose to his feet, open hand raised as if to strike his sister down, but then just as quickly seated himself once more, pasting a truly terrible smile of brotherly indulgence on his pink face.

“Certainly not, Chelsea. But you have just proved the reverend’s point,” he said, joining his hands in a prayerful attitude. “Women have not the intellect of men, nor do they possess the cerebral restraint necessary to combat rude and obnoxious outbursts. But I will forgive you, for it is just as the reverend has said, again, only delivering God’s message as he hears it spoken to him.”

“God talks to the man? Well, then, perhaps I should try having a small chat with God myself, and then the next time He talks to the reverend He can tell him to stop trying to rub up against my bosom as he pretends to bless me. That may not do much to enlarge my small intellect, but it might just save the reverend from a sharp kick in the shins.”

The earl sighed. “Scurrilous accusations will get you nowhere, Chelsea, and only show your willingness to impugn the reverend’s character by spouting baseless charges in order to … in order to get your own way.”

“Forgot the rest of the words, did you? I mean it, Thomas, you’re a parrot. You’re devout by rote, certainly not by inclination.”

“We aren’t discussing me, we’re discussing you.”

“Not if I don’t want to, and I don’t!”

“We’ve moved beyond what you want, Chelsea. You’ve had your opportunities. Three Seasons, and you’re still unwed, and very near to being on the shelf. Papa was much too indulgent of your fits and starts, and you missed a Season as we mourned his passing, may the merciful Lord rest his soul. Now we are halfway through yet another Season, and you have thus far refused the suits of no fewer than four gentlemen of breeding.”

“And one out-and-out fortune hunter who had you entirely hoodwinked,” Chelsea reminded him as she paced the carpet in front of the desk, unable to remain still. Her brother had always been stupid. Now he was both stupid and holy, hiding his fears behind this new supposed devotion, and that somehow made it all worse. She believed she’d liked him better when he’d been just stupid.

“Be that as it may, and there is still a question on that head, if you will not choose a husband, it is left to me to select one for you, as I helped do for your sister. You should be immensely flattered that he has taken an interest, most especially as he has firsthand knowledge of your … your proclivity for obtrusive behavior. I can think of no one finer than Reverend Flotley.”

“You open your mouth yet again, Thomas, but it’s still Francis Flotley’s words that come out of it. I can think of no one worse. I’d rather wed a street sweep than put myself in the power of that religious mountebank. I reach my majority in a few weeks, Thomas, and you cannot order me to marry that … that oily creature. Oh, stop frowning. A mountebank, since you obviously aren’t of a superior enough intellect to know, is a person who deceives other people for profit. Sometimes it is by selling false cures, and for the reverend, it is selling false salvation. You really think he has a direct conduit to God? I hear Bedlam is full of those who think God speaks to them. You could ask any one of them to intercede for you without paying them a bent penny, and I can go my own way.”

“And where would that be, Chelsea?” Her brother was maintaining his composure, something he had struggled long and hard to do ever since he’d nearly died during a bout with the mumps two years earlier, passed to him by one of Madelyn’s wet-nosed brood of brats—It having taken Madelyn a run through a pair of female offspring before she’d succeeded in producing a male heir for her husband, who’d then at long last agreed to leave her alone, so she was free to regain her figure, buy out Bond Street every second fortnight and sleep with any man who wasn’t her husband.

At any rate, and Madelyn’s disease-spreading offspring to one side, Thomas was devoutly religious now, having promised God all sorts of sacrifices in exchange for rising up from what could have been his deathbed, and it had been the Reverend Francis Flotley who had successfully delivered, and continued to deliver, the earl’s messages to God in his name.

Since their father’s untimely death and Thomas’s own near brush with that final answer to the trial of living, the earl no longer drank strong spirits. He did not gamble. He’d given his mistress her congé and was now, for the first time in their marriage, faithful to his wife—who, Chelsea knew, was none too happy about that turn of events. He wore expensive yet simple black suits with no ornamentation. He did not lose his temper. He read the evening prayers in the drawing room each night at ten and retired at eleven.

And he continued to pour copious amounts of money into the purse of Reverend Flotley, who, Chelsea believed, had decided marrying the earl’s younger sister to be a guarantee that the supply of funds would then never be cut off, even if his lordship were ever to suffer a crisis of faith … or meet another lady of negotiable moral standards he might want to set up in a discreet lodging somewhere.

“Where would I be? Are you threatening to toss me into the streets, Thomas?”

He sighed. “I did not wish for it to come to this, but I have sole control over your funds from Mama until you are married. You have a roof over your head because of my generosity. You have bread on your plate and clothes on your back because I am a giving and forgiving man. But more to the point, Francis and I see your immortal soul in danger, Chelsea, thanks to your headstrong and modern ways. I’m afraid you leave me no choice but to make this decision for you. The banns will be called for the first time this Sunday at Brean, and you and the reverend will be wed there at the end of this month.”

Chelsea was caught between panic and anger. Anger won. “The devil we will! You think you almost died, and your answer to that is to sacrifice me? I thought it was only your cheeks that got fat—not your entire head. I won’t do it, Thomas. I won’t. I’d rather reside beneath London Bridge.”

The earl opened the book of sermons and lowered his gaze to the page, signaling that the interview was concluded. But he could not conceal that his hands were shaking, and Chelsea knew she had nearly succeeded in rousing his temper past the point the Reverend Flotley had deemed good for her brother’s soul. “Not London Bridge at least. We leave for Brean in the morning, where you will be made safe until the ceremony.”

Chelsea felt her stomach clench into a knot. He was planning to make her a prisoner until the wedding. “Made safe? Locked up, that’s what you mean, don’t you? You can’t do that, Thomas. Thomas! Look at me! I’m your sister, not your possession. You can’t do that.”

He turned the page, ignoring her.

She whirled about on her heel and fled the room, her mind alive with bees and possibilities … and filled with one thought in particular, a memory that had been conjured up thanks to Thomas.

When she reached the main foyer she told the footman to order her mare brought round and then raced up the sweep of staircase to change into her riding habit before her brother came to his senses and realized that a prisoner tomorrow, warned of that pending imprisonment, should also be a prisoner today.

“So, I’ve been lying here thinking, and I’ve come up with a question for you. Are you ready? Hell and damnation, man, are you even awake?”

There was a muffled and faintly piteous groan from somewhere in the near vicinity, and Beau turned his head on the couch cushion—not without experiencing a modicum of cranial discomfort—to see his youngest brother lying on the facing couch, facedown and still fully dressed in his evening clothes. Although one of his black evening shoes seemed to have gone missing.

“A moan is sufficient, thank you. Now, here it is, so pay attention if you please—how drunk is it to be drunk as a lord?” Beau Blackthorn asked Robin Goodfellow Blackthorn, affectionately known to his siblings and many friends as Puck.

“Sterling question, Beau, sterling. Not sure, though,” Puck, yet another victim of their dear actress mother’s intense admiration for William Shakespeare, replied, lifting his head and squinting through the long, dark blond hair that fell across his face as he commenced staring intently at a brass figurine depicting a scantily clad goddess with six—no, eight—oddly extended and bent arms. At least he probably hoped that was it, because if there were, in reality, only two arms, then he was as drunk as any lord had been in the history of lords. “Twice as drunk as a … a what’s it called? Three wheels, place to pile things. Dirt, stones. Turnips. Wait, wait, I’ll figure it out. Oh, right. A wheelbarrow? That’s it, drunk as a wheelbarrow.”

Beau stared at the half-empty wine bottle he held upright against his chest as he lay sprawled on the matching couch in the drawing room, realizing that he no longer possessed any urge to relieve it of the remainder of its contents. Not if he was still drunk enough to be asking his irreverent and weak-brained brother for answers to anything. Besides, his stomach was beginning to protest, threatening to throw back what had already been deposited in it.

“Still the half-wit, aren’t you, Puck? Wheelbarrows don’t drink. Stands to reason. They don’t have mouths. Remember old Sutcliffe? He once said he was drunk as David’s sow. Don’t know any Davids, do you? One with a sow, remember, that’s the important part. Not enough to know a David. Has to be a sow in there somewhere.”

“David Carney is married to a sow,” Puck said, grinning. “Says so all the time. I’ve seen her, and he’s right. Are we still drunk, do you think? Shouldn’t be, not seeing as it’s light outside those bloody windows over there, and the mantel clock just struck twelve while you were talking sows. Or that might have been eleven. I may have lost count. Or perhaps we’re dead?”

“The way my head is beginning to pound, that might be best, but I don’t think so. Now, back to the point. I’m drunk, you’re drunk. We’re drunk as bastards, surely. But are we as drunk as lords? Can bastards be as drunk as lords?”

“You going to start prattling on again about bastards and lords? Thought we’d done with that by the time we’d cracked the third bottle. Bastards, I have found, can’t be anything as lords,” Puck said, cautiously levering himself upward far enough to swivel about and sit facing his brother. He pushed his hands straight back through his nearly shoulder-length hair, so that he could tuck it behind his ears. “See my ribbon anywhere? It’ll all just keep falling in my eyes otherwise.”

“I could ring for somebody to fetch Sidney. The man owns a scissors, which is more than I can say for your valet.”

“Blasphemy! The ladies would never forgive me. My hair is a necessary part of my considerable charms, don’t you know. If I am to be Puck, then I shall be Puck. Mischievous. A sprite, a magical woodland creature.”

“And none too bright.”

“Ha! So you say. But still, much better-looking and virile, and definitely more amusing. Every maiden’s dream, although I’ve not much time for maidens. They demand so much wooing, and once you’ve finally got them into bed they don’t know what they’re doing. By and large, a dreadful waste of time.”

Beau had also sat up and placed the wine bottle on the floor, next to the table positioned between the pair of couches, so that he could better rub at his aching head. “Is that it? Are you done now? Because there are times I think you’ll never truly grow up. I left and you were a child, and I came back to find you older, yet no wiser.”

Puck merely shrugged, clearly not taking offense at his brother’s words, as a less confrontational fellow would be difficult to locate within the confines of England. “You long for acceptance where there is no acceptance. Brother Jack would spit in the eye of anyone who dared to call him respectable. And I? I applaud myself for my complete indifference to it all. I have more money than any ten men with rich appetites would ever need, thanks to our guilt-ridden father. I have been educated and dressed up and taught to be mannerly, and there is nothing left for me to aspire to than to be happy with my lot. Which, brother mine, I am. Besides, you and Jack are deadly serious enough for all of us. Some one of us should have some fun. You look like hell, by the way. I must remember to give up strong spirits before I reach your age.”

At last, Beau smiled. “You’re only four years my junior, and at thirty I’m far from tottering about with one foot hovering over a grave.” But then he stabbed his fingers through his own thick shock of sun-streaked blond hair. “Although, at the moment, I might consider it. I don’t remember the last time I felt like this. You’re a bad influence, little brother. One might even say noxious. When do you return to France?”

“Hustling me back out the door only a few days after I’ve come through it, and after only a single night’s celebration of my return to the bosom of my wretched family? Papa keeps this great pile for all of us, you know. Why, I might just decide to take up permanent residence in London. Wouldn’t that be fine? Just the two of us, rattling around here together, driving the neighbors batty to know that there are now two Blackthorn bastards in residence rather than just the one. Never be all three, considering Black Jack won’t come within ten miles of the place.”

Beau attempted to straighten his badly wilted cravat. “Oh, he’s been here. Haughty, grumpy, scowling and bloody sarcastic. Don’t wish him back, if you don’t mind. Neither of us would like it.”

“He would have made a fine Marquess, aside from the fact that you’d be first in line. And if our dearest mother had deigned to marry our doting papa. There is still that one other niggling small detail.”

“Jack wouldn’t take legitimacy if someone were to hand it to him on a platter. He likes being an outlaw.”

Puck raised one finely arched eyebrow. “You mean that figuratively, don’t you? Outlaw?”

“God, I hope so. Sometimes, though, I wonder. He lives damn well for a man who refuses our father’s largesse. I’d reject it, as well, if it weren’t for the fact that I do my best to earn my keep, running all of the Blackthorn estates while you fiddle and Jack scowls.”

“Yes, I admit it. I much prefer to gad about, spending every groat I get and enjoying myself to the top of my bent, and feel totally unrepentant about any of it.”

“You’ll grow up one of these days. We all do, one way or another.” Beau got to his feet, deciding he could not stand himself one moment longer if he didn’t immediately hunt out Sidney and demand a hot tub to rid him of the stink of a night of dedicated drinking with Puck.

“He’s lucky with the cards? The dice?” Puck persisted, also getting to his feet, triumphantly holding up the black riband he then employed to tie back his hair.

“I don’t know. I don’t ask. Jack was never one for inviting intimacies. Now come along, baby brother. We need a bath and a bed, the both of us.”

“You might. I’m thinking lovely thoughts about a mess of eggs and some of those fine sausages we had yesterday morning.”

Beau’s stomach rolled over. “I remember when I could do that, drink all night and wake clearheaded and ravenous in the morning. You’re right, Puck. Thirty is old.”

“Now you’re just trying to frighten me. Ho, what’s that? Was that the knocker? Am I about to meet one of your London friends?”

“Acquaintances, Puck. I have no need of friends.”

“Now that is truly sad,” his brother said, shaking his head. “You had friends, surely, during the war?”

“That was different,” Beau said, his headache pounding even harder than before. “Soldiers are real. Society is not.”

“The French are much more generous in their outlook. To them, I am very nearly a pet. A highly amusing pet, naturellement. My bastard birth rather titillates them, I think. And, of course, I am oh, so very charming. Ah, another knock, followed closely by a commotion.” Puck headed for the foyer. “This becomes interesting. I’d think it was a dun calling to demand payment, but you’re entirely too deep in the pocket for that. Let’s go see, shall we?”

Beau opened his mouth to protest, but quickly gave that up and simply followed his brother into the foyer. There they saw a woman, her face obscured by the brim of her fashionably absurd riding hat, quietly but fiercely arguing with Wadsworth.

“Wadsworth?” he said questioningly, so that his Major Domo—once an actual sergeant in His Majesty’s Army—turned about smartly, nearly saluting his employer before he could stop himself.

“Sir!” he all but bellowed as he tried to position his fairly large body between that of the female and his employer. “There is someone here who demands to be seen. I am just now sending her on the right-about—that is to say, I have informed her that you are not at home.”

“Yes, well I suppose we needs must give that up as a bad job, mustn’t we, now that I’ve shown myself. Or do you think she’ll agree to go away now?”

“She most certainly will not,” the woman said from somewhere behind Wadsworth. And then a kid-riding-glove-encased hand was laid on Wadsworth’s elbow and the man who had once single-handedly subdued a half dozen Frenchmen during a skirmish by means of only his physical appearance and commanding voice—and the bloodied sword he’d held in front of him menacingly—was rudely shoved aside.

The woman’s gaze took in the two men now before her, sliding from one to the other. “Oliver Blackthorn? Which one of you is he? And the other must be Mr. Robin Goodfellow Blackthorn, as I hear the third brother is dark to your light, unless that’s simply a romantic statement and not fact. Such an unfortunate name, Robin Goodfellow. Did your mother not much like you? Oh, wait, you are Oliver, aren’t you?” she said, pointing a rather accusing finger at Beau. “I believe I recognize the scowl, even after all these years. We must talk.”

“Gad, what a beauty, if insulting,” Puck said quietly. “Tell her she’s wrong, that I’m you. Unless she’s here to inform you that the bastard has fathered a bastard, in which case I’ll be in the breakfast room, filling my belly.”

Beau wasn’t really listening. He was too busy racking his brain to remember where he’d ever seen eyes so strange a mix of gray and blue, so flashing with fire, intelligence and belligerence, all at the same time.

“You remember me, don’t you?” the young woman said—again, nearly an accusation. “You should, and the mumps to one side, you’re a large part of the reason I’m in such dire straits today. But that’s all right, because now you’re going to fix it.”

“She said mumps, didn’t she? Yes, I’m sure she did. I’ve been abroad for a few years, brother mine. Are they now in the habit of dressing up the Bedlamites and letting them run free on sunny days?”

“Go away, Puck,” Beau said, stepping forward a pace, putting a calm face on his inward agitation. “Lady Chelsea Mills-Beckman?” he inquired, positive he was correct, although it had been more than seven long and eventful years since last he’d seen her. But why was she here? And where was her maid? Maybe Puck was right, and if not quite a fugitive from Bethlehem Hospital, she was at least next door to a Bedlamite; riding out alone in the city, calling on him, of all people. “To what do I owe the pleasure?”

“Ah, so you do remember me. And there’s nothing all that pleasurable about it for either of us, I assure you. Now, unless you are in the habit of entertaining your servants with aired laundry best discussed only in private, I suggest we adjourn to the drawing room. Notyou,” she added, pointing one gloved finger at Puck, who had already half turned to reenter the drawing room.

“Oh, yes, definitely. You heard the lady. It’s you she wants, brother mine, not me. I’m off, and may some merciful deity of your choosing protect you in my craven absence.”

“Wadsworth,” Beau said, still looking at Lady Chelsea, “the tea tray and some refreshments in ten minutes, if you please.”

Lady Chelsea stood her ground. “Wadsworth, a decanter of Mr. Blackthorn’s best wine and two glasses, now, and truth be told, at the moment I really don’t much care whether you please or not. Mr. Blackthorn, follow me.”

She then swept into the drawing room, leaving Wadsworth and Beau to look at each other, shrug and supposedly do as they’d been told. That was the thing with angry women. Experience had taught Beau that it was often just easier to go along with them until such time as you could either locate a figurative weapon or come up with a good escape route.

And Beau did long for escape, craven as that might seem. The moment he’d recognized Lady Chelsea the memory of the last time he’d seen her had come slamming into his mind, rendering him sober and none too happy to be thinking so clearly.

His reunion with Puck had given him the chance to relax the guard he’d so carefully built up around himself. They’d laughed, definitely drunk too much and Beau had realized how long it had been since he’d allowed himself to be young and silly.

Only with his brother could he joke about their bastard births, make light of the stigma they both would carry for all of their lives. Puck seemed to be dealing with his lot extremely well, although he had attacked the problem from an entirely different direction.

Where Beau thought to gain respect, if not acceptance, Puck had charmed his way into French Society.

Jack? Jack didn’t bear thinking about, as he seemed to be a law unto himself.

But no matter the path Beau had chosen, he knew he’d come a long way from the idiot boy he’d been seven long years ago. He’d put the past behind him—except for what he believed to be the one last piece of unfinished business that had brought him to London—and he would rather the door to that part of his life remain firmly shut.

Shut, and with Lady Chelsea firmly on the other side. She with her childish teasing and then her sympathetic tears. If anything could have taken him to his knees that day, and kept him there, it would have been the sight of her tears.

“Sir?”

Beau turned to look at Wadsworth, snapping himself back into the moment. “Yes?”

“Are we going to do what she says, sir?” The man screwed up his face for a moment, and then shook his head. “Got the air of a general about her, don’t she, sir?”

“That she does, Wadsworth,” Beau said, at last turning toward the drawing room. “That she certainly does….”

CHAPTER TWO

HE HADN’T REALLY CHANGED in seven years. Except that he definitely had. He seemed taller, appealingly thicker in muscle, she supposed. He still carried his arrogance with him, but that had been joined now by considerably more self-assurance. His cheeks seemed leaner, his jaw more defined. He’d been only a year older then than she was now, and had obviously lived an interesting life in the interim.

He’d impressed her then, silly as he’d been in his embarrassing calf-love for Madelyn, uncomfortable as he’d looked in his ridiculously over-tailored clothes, gullible as he’d been when she’d teased him. Vulnerable as he had been, lying in the street as Thomas had brought the whip down over his body, again and again.

She’d had nightmares about that terrible day ever since. She assumed Mr. Blackthorn had, as well.

But the years had made him a man. Going to war had made him a man. What had happened that fateful day in Portland Place had made him a man. Then, he had amused her. Now, just looking at him made her stomach rather queasy. He was so large, so very male. Not a silly boy anymore at all.

Perhaps she had acted rashly, coming here. No, she definitely had acted rashly, considering only her own plight while blithely believing he would grab at her idea with both hands, knowing immediately that she was helping him, as well.

But there was nothing else for it. She had done what she’d done. She was here, an unmarried woman in a bachelor household, and probably observed by at least two or three astonished members of the ton as she’d stood at the door and banged on the knocker. Oh, and her groom and horse were still just outside, on the street.

She couldn’t have been more open in her approach if she had ridden into Grosvenor Square shouting and ringing a bell.

Now she had to make Mr. Blackthorn—or Oliver, as she’d always thought of him—understand that there was no going back, for either of them. She may be frightened, suddenly unsure of herself—such a rare occurrence in her experience that she wasn’t quite sure how to handle it—but she would not allow him to see her fear.

“You look as if you’ve been dragged through a hedgerow backward,” she told him as she stood in the middle of the sumptuously furnished drawing room, pulling off her kid gloves, praying he wouldn’t notice that her hands were shaking. “And you smell none too fresh. Is this your usual state? Because if it is, my mind won’t change, but you will definitely have to.”

He reached for a jacket that was hanging over the back of a chair and then seemed to think better of it, remaining in front of her clad only in his buckskins and shirtsleeves. “Much as it pains me to disagree with you, Lady Chelsea, I don’t have to do anything I don’t want to do. Bastardy has its benefits as well as its drawbacks.”

She rolled her eyes, suddenly more comfortable. He might not appear vulnerable, but clearly he still carried the burden of his birth around with him; it must be a great weight he would choose to put down if he had the chance. “Are you still going on about that? You are, aren’t you. That’s why you’ve been slowly ruining my brother.”

Beau frowned just as if he didn’t understand her, which made her angry. She knew he wasn’t stupid.

“Don’t try to deny it, Mr. Blackthorn. You’ve sent person after person to insinuate himself with Thomas this past year, guide him down all the wrong paths, divesting him of our family’s fortune just as if you had been personally dipping your hand into his pockets. Granted, my brother is an idiot, but I, sir, I am not.”

“Nor are you much of a lady, traveling about London without your maid, and barging uninvited into a bachelor establishment,” Beau said, walking over to one of the couches positioned beneath an immense chandelier that, if it fell, could figuratively flatten a small village. “Then again, I am not a gentleman, and I am curious. Stand, sit, it makes me no nevermind, but I’ve had a miserable night and now it appears that the morning will be no better, so I am going to sit.”

Chelsea looked at the bane of her existence, who was also her only possibility of rescue, and considered what she saw. He was blond, even more so wherever the sun hit his thick crop of rather mussed hair, so she hadn’t at first noticed that he had at least a one-day growth of beard on his tanned cheeks. He looked rather dashing that way, not that she would tarry long on the path to that sort of thought. He also looked—as did this entire area of the large room, for that matter—as if the previous night had been passed in drinking heavily and sleeping little.

Good. He probably had a crushing headache. That would make him more vulnerable.

“Yes, do that, sit down before you fall down, and allow me to continue. In this past year, which happens to coincide with Thomas reentering Society after our year of mourning that also gained him the title, and paired with your return to London now that the war is finally over, we have been visited upon by a verifiable plague of financial ill-fortune, one to rival the atrocities of the Seven Plagues of Egypt.”

Beau held up one hand, stopping her for a few moments, and then let it drop into his lap. “All right. I’ve run that mouthful past my brain a second time, and I think I’ve got it now. Your brother, the war, my return after an absence of seven years—and something about plagues. Are locusts involved? I really don’t care for bugs. But never mind my sensibilities, which it is already obvious you do not. You may continue.”

“I fully intend to. You know the locusts to which I refer. Mr. Jonathan Milwick and his marvelous invention that, with only a small input of my brother’s money, could revolutionize the manufacture of snuff. The so-charming Italian, Fanini, I believe, whose discovery of diamonds in southern Wales would make Thomas rich as Golden Ball.”

Beau closed his eyes and rubbed at his temples. “I have no idea what you’re prattling on about.”

“Still, I will continue to prattle. The ten thousand pounds Thomas was convinced would triple in three weeks’ time in the Exchange, thanks to the advice of one Henrick Glutton, who would share his largesse with Thomas once his ship, filled with grapes to be made into fabulously expensive wine, arrived up the Thames. I went with Thomas to the wharf when the ship arrived. Have you ever smelled rotten grapes, Mr. Blackthorn?”

“Glutten,” he said rather miserably.

“Ah! So you admit it!”

“I admit nothing. But nobody can possibly be named Glutton. I was merely suggesting an alternative. Excuse me a moment, I just remembered something I need.” Then he reached down beside him to pick up a bottle that had somehow come to be sitting on the priceless carpet, and took several long swallows straight from it, as if he were some low, mannerless creature in a tavern. He then held on to the bottle with both hands and looked up at her, smiling in a way that made her long to box his ears. “You were saying?”

“I was saying—well, I hadn’t said it yet, but I was going to—I don’t blame you for any of it. Thomas deserves all that you’ve done, and more. But with this last, you’ve overstepped the mark, because now you’ve involved me in your revenge, and that I will not allow. Still, I am here to help you.”

The bottle stopped halfway to his mouth. At last she seemed to have his full attention. “I’m sorry, I don’t follow. You’re going to help me? Help me what, madam?”

Chelsea held her tongue until Wadsworth had marched in, deposited a silver tray holding two glasses and a decanter of wine on the table and marched out again.

“I haven’t made a friend there, have I?” she commented, watching the man go. And then she shrugged, dismissing the thought, and finally seated herself on the facing couch and accepted the glass of wine Beau handed her. “You know that my brother became horribly ill only a few weeks after our father died. It was believed he’d soon join Papa in the mausoleum at Brean.”

“I’d heard rumors to that effect, yes,” Beau said carefully, shunning the decanter to take another long drink from the bottle. “Am I to be accused of that, as well? The illness, perhaps even your father’s demise? Clearly I have powers I have not yet recognized in myself.”

“Papa succumbed to a chest ailment after being caught in the rain while out hunting, so I doubt his death could be laid at your door. It was Madelyn’s brood, come to Brean for the interment and bringing their pestilence with them, who nearly killed Thomas just as he was glorying in his acquisition of the title. You had a victory there, didn’t you? With Madelyn, I mean. Thomas’s vile behavior that day had repercussions on my idiot sister, and she had to be married off quickly in order not to have all the ton staring at her belly and counting on their fingers. Do you remember what Thomas screeched at you that day? Something about you taking advantage of her innocence? Poor Madelyn, hastily bracketed to a lowly baron when she had so set her sights on a duke, but she couldn’t convince Papa. That you and she hadn’t—you know. And poor baron, as he’s had to live with her ever since. You had a lucky escape, Mr. Blackthorn, whether you are aware of it or not.”

His blue eyes narrowed, showing her that she had at last touched a nerve. “You term what happened that day a lucky escape? Your memories of the event must differ much from mine.”

“You’re still angry.”

Beau leaned against the back of the couch and crossed his legs. “Anger is a pointless emotion.”

“And revenge is a dish best served cold. Thomas humiliated you for all the world to see, whipped you like a jackal he refused to dirty his hands on. The woman you thought you loved with all your heart turned out not to possess a heart of her own. Between them, my siblings brought home to you that you are what you are, and that Society had only been amusing itself at your expense, while it would never really accept you. I would have wanted them dead, all of them.”

“Thank you for that pithy summation. I may have forgotten some of it.”

“You’ve forgotten none of it, Mr. Blackthorn, or else I would not be saddled with Francis Flotley. I, who remain blameless in the whole debacle, a mere child at the time of the incident. Do you think that’s fair? Because I don’t. And now you’re going to make it right.”

“You’re here to help me, and yet I’m supposed to make something right for you.” Beau looked at her, looked at the bottle in his hand and then looked at her again. “Much as it pains me to ask this, what in blazes are you talking about? And who the bloody hell is Francis Flotley?”

Chelsea’s hands drew up into fists. She wasn’t nervous anymore. It was difficult for one to be nervous when one was beginning to feel homicidal. “You admit to Henrick Glutton and the others? We can’t move on, Mr. Blackthorn, until you are willing to be honest with me.”

“Glutten,” he said again, sighing. “And the others. Yes, all right, since you clearly won’t go away until I do, I admit to them. Shame, shame on me, I am crass and petty. But, to clarify, I’m not out to totally ruin the man, but only make him uncomfortable, perhaps even miserable. Ruining him entirely would be too quick. As it is, I can keep this up for years.”

“Why?”

“I should think the answer to be obvious. Because it amuses me, madam,” Beau said flatly. “Rather like pulling the wings from flies, although comparing your brother to a fly is an insult to the insect. I’m unpleasantly surprised, however, that you connected me with your brother’s run of ill luck, although I should probably not be, remembering you as you were. A pernicious brat, but possessing higher than average intelligence.”

It was taking precious time, but at least they were finally getting somewhere. “So you admit to Francis Flotley.”

“If you’ll just leave me alone with my pounding head, I’ll admit to causing the Great Fire. But I will not admit to Francis Flotley, whoever the hell he is.”

Chelsea sat back in her seat. She had been so certain, but Beau clearly did not recognize the name.

“Francis Flotley,” she repeated, as if repetition would refresh his memory. “The Reverend Francis Flotley, Thomas’s personal spiritual adviser. The man who interceded with God for him in order to save him from the mumps in exchange for his promise to mend his ways. You used Thomas’s vulnerability to insinuate the man into our household, to defang the cat, as it were, make him believe that he had to give up drink, and loose women, and his rough and tumble ways, in order to save his immortal soul. Curb his vile temper, turn the other cheek—all of that drivel. A man who would whip another man in the street, reduced to nightly prayers and soda water, doing penance for his crime against you, even if he doesn’t realize that he is, lacking only sackcloth and ashes. How that must please you.”

“Ah. The Reverend Francis Flotley. Yes, I will admit that I am aware of a cleric’s presence in your household,” Mr. Blackthorn said, sitting forward once more. “But no, sorry. I had nothing to do with that. Wish I had, though, having once been at the wrong end of what you call your brother’s vile temper. It sounds a brilliant revenge.”

Chelsea sat slumped on the couch, like a doll suddenly bereft of all its cotton stuffing. “Oh,” she said quietly, seeing her last and only hope fading into nothing. “I’d been so sure. So brilliantly Machiavellian, you understand. I have given you too much credit. Forgive me. I’ll go now.”

She got to her feet and picked up her gloves, putting them on slowly, giving him time to sift through everything she’d told him. Surely he wouldn’t let her leave. He couldn’t. He had to at least be curious as to what she’d meant about having her own life ruined, and that she’d come here to help him. Even if she hadn’t been correct about the Reverend Flotley, perhaps her plan could still work.

But Beau stayed where he was, not even rising because she had stood up, and very much ignoring her, as if she’d already gone. Perhaps he wasn’t the man she’d built him into in her head. Perhaps he was just as bad as her brother in his own way.

Still, knowing she had no other options, she dared to continue hoping, even as she walked toward the foyer, slowly counting in her head. One. Two. Three. Four. Oh, for pity’s sake, I’m here to hand you the perfect revenge, you jackass! Does it really matter that you didn’t send Flotley to us? Five. Six …

“Wait a moment.”

Chelsea closed her eyes for a second, swallowed her fear once more and then turned around. “Yes? Has the penny finally dropped, Mr. Blackthorn? I’ll excuse you, considering your drunken state, but you really shouldn’t have taken much past three. If I’d gotten to nine, I’d have needed to reassess my opinion of you.”

Beau got to his feet, waving a hand in front of him as if erasing whatever she’d said as not worthy of a response. “Why did you come here? Alone? Not just to crow over me that you know what game I’ve been playing with your brother. And more importantly, why do I get the feeling that you’re not here to help me as much as you’re here to help yourself? Wait—don’t answer yet. Sit, drink your wine, and I’ll go stick my head in a basin of cold water and clean up some of my mess, in the hope it clears my head.”

“Yes, all right,” Chelsea answered, once again taking up both her seat and the wineglass. She didn’t really drink wine; she’d ordered it for him, believing he’d need it after he’d heard what she had to say. “But we should be leaving here within the hour, and even that will probably be cutting it too fine for comfort.”

“Leaving? We? As in, the two of us? Oh, really. And to travel where, may I ask?”

“You’re wasting time, Mr. Blackthorn. My brother is far from an intellectual, but he isn’t completely stupid, either. He’ll soon be out and about, looking for me, his newfound docile nature stretched to the breaking point. Oh, and to that end, although it is reminiscent of barring the barn door after the cow has escaped, I suggest you have my mount and groom removed from in front of the building.”

“I’ll order that,” the other Mr. Blackthorn volunteered, halting just inside the doorway, a thick slice of bacon in his hand. “Shall we have the fellow bound and gagged, Lady Chelsea, or simply sat down somewhere and told to stay put? Beau, brother mine, clearly you’ve been holding out on me. I had no idea you led such an interesting life.”

Beau grumbled something Chelsea was too far away to hear—which was probably a good thing—and headed for the stairs, bounding up them two at a time.

“Good, he’s gone. Now we two can get to know each other better, as it appears you and my brother are up to some sort of mischief. Or is it just you? He is looking rather harassed. It’s his age, you understand. Can’t hold his drink anymore, either. It’s a curse, old age. I have just now, over a plate of coddled eggs, vowed never to succumb to it.”

“My mount, Mr. Blackthorn,” Chelsea told him, smiling in spite of herself, for Mr. Robin Goodfellow Blackthorn had the most engaging smile and way about him. “And after you’ve gone off to do that, please order your brother’s horse saddled and have his man pack a small bag for him. A traveling coach would be much too slow and easily spotted for our needs for now, I believe. We may also, now that I have a moment to reflect on the thing, needs must keep to alleyways until we’re clear of London.”

The man opened his mouth, clearly to ask her what she meant, but she merely pointed behind him, to the foyer. “This is life or death, Mr. Blackthorn, so there is no time for me to stand here and applaud your silliness. Go.”

He went.

Chelsea took a sip of the wine.

It didn’t help; she was still shaking.

CHAPTER THREE

MUCH TO THE CHAGRIN of his valet, Beau refused to take the time to sit and be shaved, opting for a quick wash at the basin, a brief encounter with his tooth powder and a rushed combing of his hair as Sidney helped him into a clean white shirt before handing him fresh linen and buckskins and then throwing up his hands in disgust and quitting the dressing room.

Beau was still having difficulty believing that Lady Chelsea Mills-Beckman, sister of his nemesis, was downstairs, sipping wine in his drawing room. Sans chaperone, clad in a rather startlingly red riding habit and clearly expecting him to go somewhere with her.

Lady Chelsea Mills-Beckman. Knowing things she shouldn’t know. Cheeky and impertinent as she’d been as a girl … and hinting of helping him revenge himself on her brother.

While helping herself. He shouldn’t forget that. Women with ulterior motives were the norm rather than the oddity, he’d learned, and as this woman was also intelligent, he would have to be doubly on alert.

“Well, that could be considered by the less discerning as a bit of an improvement, I suppose,” Puck said, entering the dressing room to lean one shoulder against the high chest of drawers as he visually assessed his brother. “I have reconnoitered your visitor, grilling her mercilessly for details. She informs me whatever is going on is a matter of life or death. Worse, she seems astonishingly immune to my charms, which would have me descending into a pit of despair were it not that I’m secretly delighted that she has targeted you rather than me for whatever it is she’s planning. Not that I’m not here to help.”

Beau snatched up a neck cloth and hastily tied it around his throat. “Your enthusiasm for throwing yourself down in the path to protect me nearly unmans me,” he grumbled, realizing he’d just tied a knot in the neck cloth—rather like a noose.

“You’re welcome. Disregarding female enthusiasm for melodrama, do you think she’s right? The brother is a nasty piece of work, as I recall. Are you sure you wish to become embroiled in whatever she’s prattling on about?”

“She’s in my house, Puck.”

“Our house, not to quibble about such a small point. But, as I am also here, I believe I should be apprised of whatever the devil it is I’ve somehow become embroiled in myself, if only by association. She’s ordered me to hide her horse and groom, and then to advise Sidney to pack a bag for you, as you will be leaving within the hour. Which, naturally, begs the question—where are we going?”

Beau shrugged into a hacking jacket and took one last, quick look at his reflection in the mirror above the dressing table. “We are not going anywhere,” he told his brother. “Whatever the mess, I brought it on myself by being idiot enough to think I was a cat, toying with a mouse. I should have let it go, Puck, years ago. But, for once, it’s my idiocy, not yours. You’re not involved.”

“What? You’d leave me here to face the wrath of the brother? I think not. If I’m not to go with you, I’ll inform Gaston to pack me up and I’ll be back off to Paris. The weather is better, for one thing, and the food at least edible. I damn near cracked a tooth on that bacon our cook dared serve me. We should sack him.”

Beau turned on his brother. “You do this just to annoy me, don’t you?”

Puck pushed himself away from the dresser. “Yes, but I’ll stop now. You’re much too easy to rile, you and Jack both. Takes the joy right out of a fellow. I was listening from the terrace, you know, and heard most of what she said. You’ve really been quietly ruining the earl? I’d say that was brilliant, except that Lady Chelsea found you out, so you couldn’t be overly credited for subtlety. Comparing you to Machiavelli? Hardly. And now your pigeons seem to have come home to roost.”

“We can’t know that. Not unless the damned woman left her brother a note before she ran off. Because she did run off, Puck, that much is obvious. It’s what women do. Without a thought to anyone else perhaps not agreeing to become an actor in their small melodrama.”

“Yes, you’re right,” Puck agreed as he followed Beau down the hall to a small room he used as his private study. “She would have been better off applying to Mama. She dearly adores a melodrama. But when I left her to come to town, she was about to begin a tour of the Lake District with her troupe. I hadn’t the heart to tell her she’s getting a little long in the tooth to play Juliet, but as long as Papa finances the troupe, she has her pick of roles and no one gainsays her. Are you listening to me? What are you doing messing around in that cabinet?”

Beau turned back to his brother, the wooden case that held a pair of dueling pistols in his hands. He then opened a long wooden box kept on a sideboard and pulled out both the sword and belt he’d taken to war with him and a short, lethal-looking knife kept safe inside its sheath. “See that these are taken downstairs, if you please. I probably won’t need the sword, but I know I’ll want the knife.”

Puck frowned as the weapons were thrust at him. “Really? Would you be wanting me to hunt up a piece of field artillery as well while I’m at it? You really think the brother will come here, don’t you?”

“I was unprepared once, Puck. That won’t happen again. Now, take yourself off and do what you said you were going to do—get yourself prepared to return to Paris. This may all come to nothing, but the girl knows things she shouldn’t have guessed, and I’m going to believe her until she says something that changes my mind. Damn, what a morning—if I’d known this last night I wouldn’t have crawled so far into the bottle with you.”

“Yes, of course, blame me. It was a terrible thing, how I held your nose pinched shut and poured three bottles of wine down your gullet as we celebrated your birthday.”

“In case you’re about to add that the woman downstairs is some sort of birthday present from the gods, let me warn you—don’t.” Beau left his brother where he stood and headed downstairs to where Lady Chelsea was now pacing the Aubusson carpet, slapping her gloves against her palm.

She was, upon reflection—something, according to her, he didn’t have time for—a startlingly beautiful woman. He remembered that, as a child, she’d shown a promise of beauty, but that he’d believed she’d never hold a candle to her sister. Time had proved him wrong.

He’d seen Madelyn a time or two on his visits to London since his return from the war, driving in the park in an open carriage. The years had not been kind to her. She’d developed lines around her mouth, which seemed pinched now rather than pouting, and the nearly white-blond hair aged her rather than flattered her. She looked like what she was—a haughty, clearly unhappy woman.

He’d learned she had taken lovers over the years, sometimes without employing enough discretion, and her reputation, as well as her standing in Society, had suffered. For that, she blamed her brother, and the two of them had not spoken since their father’s death. She also probably blamed Beau, as well, for her fall began only after what he thought of now as The Incident.

But Beau had taken little satisfaction from any of Madelyn’s problems. To him, justice had been served up very neatly to Lady Madelyn for what she had done.

It was Thomas Mills-Beckman who had yet to feel justice come down on his neck. Hence the cat, toying with the mouse’s purse strings.

And now, pacing his drawing room, full of cryptic statements and offers to help him administer that justice, was this intriguing and maddening young woman, fallen into his hands either like a ripe plum or as the agent of disaster, clearly wanting to get some of her own back on her brother and eager to use Beau to help her.

“My brother tells me you assured him that we are embroiled in something very serious. Life or death, I believe he said—or perhaps that was you saying it? I’ll admit I’ve begun to lose track.”

She stopped pacing and looked at him, her blond head tipped to one side as she ran her clear blue-gray gaze up and down his body as if he were a horse she was considering purchasing. “You look somewhat better. Are you sober now?”

“I believe I’m heading in that general direction, yes. At least enough so that I want to make it clear to you yet again—I do not know this Reverend Flotley. I did not arrange to have him introduced to your brother, so if the rest doesn’t bother you—the smell of spoiled grapes notwithstanding—perhaps you wish to rethink whatever it is you believe you can do for me and go away. Quickly.”

“I can’t. I think we both know it’s already too late for that,” she said and then sighed. “We really don’t have time for this, but I have truly burned my bridges just by coming here so openly, and yours, as well, which I’m sure I don’t have to point out to you. I’m sorry for that, at least a little bit, but I had no other choice open to me. I left my brother a note explaining every—”

Beau slammed his fist into his palm. “I knew it! Why do women always feel they have to explain themselves?”

She straightened her slim shoulders. “I was not explaining myself, you daft man. I couldn’t allow my maid to take the brunt of Thomas’s anger, not when she helped me tie up some of my belongings and met me at the corner so that I could strap them onto my saddle without anyone being the wiser that I was leaving.”

“Oh, yes, of course. I can see the wisdom of that. He won’t turn her out without a reference now, not when you’d clearly cowed her into doing what you’d asked.”

“Oh,” Chelsea said quietly. “I hadn’t thought of that. But I didn’t tell him where I was heading. I’m not stupid.”

“Wonderful. The girl assures me she’s not stupid. Tell me, Mistress Genius, did you happen to confide your destination to your maid? Because, were I said maid, staring the loss of my position in the teeth, I do believe I’d try to save myself by being of assistance to my employer.”

Chelsea glared at him. “I could truly begin to dislike you.”

“I’ll take that as a yes,” Beau said, looking longingly at the wine decanter. “How long before he misses you and comes racing hotfoot over here, brandishing a pistol and demanding I present myself?”

Chelsea glanced assessingly at the mantel clock. “We should probably be going.”

“Yes. Going. And where would it be that we should probably be going to, madam? Oh, and one more small thing. Why? Why me? Why am I going to be helped by you, and how am I going to assist you? My mind is still a little fuzzy on those two points.”

She looked toward the clock once more. “We don’t have time for this now.”

Beau crossed his arms over his chest, prepared to stand his ground for the next fortnight. That she should wish to flee her brother’s household was commendable. That she should involve him in her escape? Not quite as laudatory. “Make time.”

“Only if you come with me now,” she told him, heading for the foyer and then unerringly turning toward the rear of the house. “Your brother has ordered your horse saddled, and both mounts await us in the stables. If we keep away from the main thoroughfares, I’m sure we can be clear of London before Thomas can pick up our scent and kill you.”

“Oh, this gets better and better,” Beau said as Puck, never to be left out of anything even remotely exciting, joined them as they passed through the green baize door that led to the servant area of the mansion. “One minute I’m fairly happily contemplating my life through the bottom of a bottle in celebration of my birthday and my brother’s return from France, and the next I’m running from someone else’s irate brother, who may already be on his way over here to save his sister from the clutches of a man who hadn’t even remembered her existence a mere hour ago.”

Chelsea stopped just at the doorway to the kitchens and turned to face him. “Shut. Up. I’ve been trying to tell you since I arrived, but you keep interrupting me. Now we have to leave, unless you really are stupid enough to want to face Thomas while you’re still so obviously intoxicated. And obnoxious, as well, although I have begun to doubt that will change much even once you’re sober again.”

“I take it all back, brother mine,” Puck said, snorting. “I think I’m beginning to like her.”

Chelsea pressed her palms to her cheeks, seemed to perhaps be counting under her breath for a few moments, and then dropped her hands to her sides and let out a breath.

“One, my brother did you a great, unforgivable harm seven years ago. Two, he is by nature a very stupid man—and easily led, as you seem already to have ascertained on your own, hence the spoiled grapes. Three, just after our father died, Thomas became very ill and thought he was going to die before he could enjoy the fruits of our father’s labors now that he was earl. Four, he truly believes that Francis Flotley came into his life as a gift from God, the same God Thomas had made all manner of promises to if only the good Lord would allow him to rise from his sickbed. Five, Francis Flotley delivered Thomas’s promises to God, personally—yes, I know that’s insane, so you can stop making those odious faces at me—and now Thomas is not only still stupid and easily led, but he thinks he is on some holy path, and in charge of my soul, which he is not! Seven—”

“I think you skipped six,” Puck corrected helpfully. “Sorry,” he added quickly, when Chelsea glared at him.

“Six,” she said heavily, “because I have chosen not to marry any man Thomas could like, he has decided to take me to Brean first thing tomorrow morning, lock me up and then marry me to Francis Flotley as soon as the banns can be read. In order to save my inferior female soul.”

“Seven,” Beau interrupted, holding up his hand, “as you were clever enough to ferret out that I am responsible for your brother’s financial plagues of locusts—don’t ask, Puck, just listen—you assumed, incorrectly, I might add, the reverend to also be one of my inventions. So that, eight, it is now my fault that you are to be bracketed to the man. Ergo, I am responsible for saving you from this fate, which I, nine, will somehow do by escorting you out of London with your brother in hot pursuit and out for my blood. For which, ten, you will offer me some sort of favor in return. To which, one, but not to worry because my list is quite short, I say no. Thank you for the honor, putting my head on the chopping block the way you have, but no.”

“I may never drink again,” Puck said quietly. “I mean, I actually think I understand this. But what could Lady Chelsea offer you that would help you? And to help you, it would follow that whatever she’d offer would somehow revenge you against her brother in a way that makes up for the audacity you had as to come to his house and, bastard that you are, besmirch the family escutcheon by asking for his sister’s hand in—uh-oh. Beau? Do you even know the route to Scotland?”

Beau looked at Chelsea—the bane of his existence at fourteen, a ripe plum fallen out of the sky seven years later. The perfect revenge against Thomas Mills-Beckman and all of London Society, wrapped up like a lovely gift and dropped into his lap.

No. He couldn’t do it. Could he? He’d prided himself on being a gentleman in a world that, for the most part, had branded him as something all but inhuman. Yes, he was taking his revenge against Brean, but that was different; it was only money.

To elope with the man’s sister, bed the man’s sister? That was not only despicable, it would be akin to signing his own death warrant if they were caught before the deed was done, the girl was deflowered and her reputation already so ruined that killing Beau could only make a bad situation worse.

Brean would be disgraced, the entire family would be disgraced.