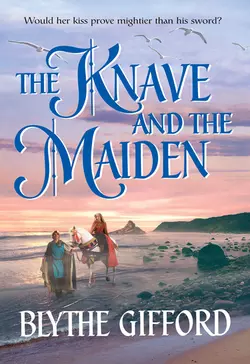

The Knave and the Maiden

Blythe Gifford

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 153.35 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: COULD A MAIDEN′S KISS TURN A CYNICAL ROGUE INTO AN HONORABLE KNIGHT?Mercenary knight Sir Garren owed much to William, Earl of Readington: his sword, his horse, even his very knighthood. And in return Garren had saved the earl′s life in the Holy Land. Yet when his liege lord fell gravely ill upon their return home, Garren knew he must save his friend once more, whatever the cost–even if it meant embarking upon a pilgrimage to pray to a long-forsaken God, or promising to deflower an innocent young woman along the way….Dominica was certain Sir Garren was a sign from heaven. Surely the pilgrimage, blessed with the presence of the handsome and heroic knight, would provide a sign of heaven′s plan for her to take the veil. But every step of the journey seemed to be leading her straight into Garren′s powerful arms. And Dominica was beginning to wonder if her true mission was to open the mercenary′s seemingly cold heart to true and lasting love.