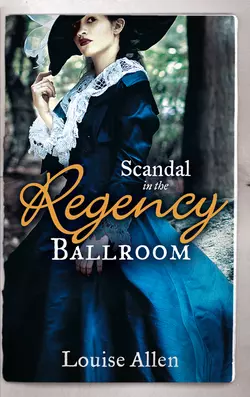

Scandal in the Regency Ballroom: No Place For a Lady / Not Quite a Lady

Louise Allen

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 774.44 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: No Place for a LadyMiss Bree Mallory hopes no one in Society will discover that she once drove the stage from London to Newbury…or that she returned unchaperoned with the rakishly attractive Max Dysart, Earl of Penrith! Yet, while beautiful Bree has no interest in marriage, Max’s kisses are powerfully persuasive…Not Quite a LadyThe wealthy and exquisite heiress Miss Lily France is determined to trade her vulgar new money for marriage to a man with a respected title. Then she meets the untitled and unsuitable Jack Lovell. His calm strength and deep grey eyes are an irresistible combination–but he is the one man she cannot buy!