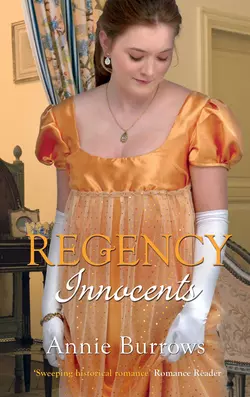

Regency Innocents: The Earl′s Untouched Bride / Captain Fawley′s Innocent Bride

Энни Берроуз

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Зарубежные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 774.44 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An earl’s choice… Fearing a forced betrothal with a man known for his cruelty, Heloise Bergeron throws herself on the mercy of Charles Fawley, Earl of Walton. He believes himself attracted to her younger, beautiful sister, so what is he doing entertaining thoughts of marriage to the plain, quiet Heloise? But marry her he does…The captain’s convenient wife…No one will agree to marry battle-scarred Captain Robert Fawley except, perhaps, Miss Deborah Gillies, a woman so down on her luck that a convenient marriage might help improve her circumstances. But once married could Deborah ever hope to reach Robert’s guarded heart? Two classic and delightful Regency tales!