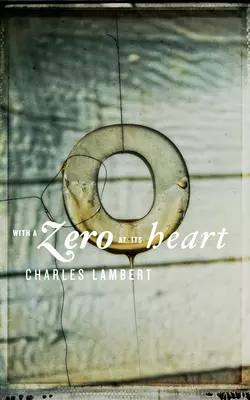

With a Zero at its Heart

Charles Lambert

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: 24 themed chapters.Each with 10 numbered paragraphs.Each paragraph with precisely 120 words.The sum of a life.In his beautiful and haunting new book, Charles Lambert explores the fragmentary nature of memory, how the piecing together of short recollections can reveal a greater narrative. Through chapters tackling elemental themes such as Sex, Death, and Money, Lambert assembles the narrator’s moving life story. Executed with all the grace and finesse of his previous acclaimed work, this is an incredible artistic achievement, breathtaking in its simplicity yet awe-inspiring in its scope.With cover design by the renowned designer Vaughan Oliver, With a Zero at its Heart is as beautiful to look at as it is to read.