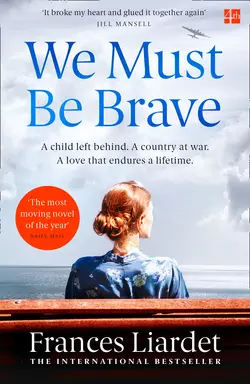

We Must Be Brave

Frances Liardet

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1246.16 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A woman; a war; a child that changed everything. Spanning the sweep of the twentieth century, We Must Be Brave is a luminous and profoundly moving novel about the people we rescue and the ways in which they rescue us back.She was fast asleep on the back seat of the bus. Curled up, thumb in mouth. Four, maybe five years old. I turned around. The last few passengers were shuffling away from me down the aisle to the doors. ‘Whose is this child?’ I called. Nobody looked back.December, 1940. As German bombs fall on Southampton, the city’s residents flee to the surrounding villages. In Upton village, amid the chaos, newly-married Ellen Parr finds a girl sleeping, unclaimed at the back of an empty bus. Little Pamela, it seems, is entirely alone.Ellen has always believed she does not want children, but when she takes Pamela into her home the child cracks open the past Ellen thought she had escaped and the future she and her husband Selwyn had dreamed for themselves. As the war rages on, love grows where it was least expected, surprising them all. But with the end of the fighting comes the realization that Pamela was never theirs to keep…A story of courage and kindness, hardship and friendship, We Must be Brave explores the fierce love we feel for our children and the astonishing power of that love to endure.