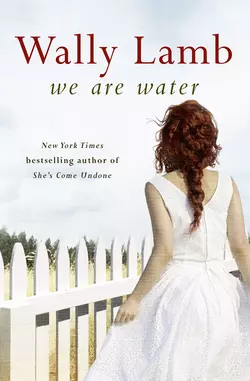

We Are Water

Wally Lamb

From New York Times bestselling author Wally Lamb, a disquieting and ultimately uplifting novel about a marriage, a family, and human resilience in the face of tragedy.As Annie Oh’s wedding day approaches, she finds herself at the mercy of hopes and fears about the momentous change ahead. She has just emerged from a twenty-five year marriage to Orion Oh, which produced three children, but is about to marry a woman named Viveca, a successful art dealer, who specializes in outsider art.Trying to reach her ex-husband, she keeps assuring everyone that he is fine. Except she has no idea where he is. But when Viveca discovers a famous painting by a mysterious local outside artist, who left this world in more than mysterious circumstances, Orion, Annie and Viveca’s new dynamic becomes fraught. And on the day of the wedding, the secrets and shocking truths that have been discovered will come to light.Set in Lamb’s mythical town of Three Rivers, Connecticut, this is a riveting, epic novel about marriage and family, old hurts and past secrets, which explores the ways we find meaning in our lives.

This one is for two strong women:

Joan Joffe Hall and Shirley Woodka

Ghost of a Chance

You see a man

trying to think.

You want to say

to everything:

Keep off! Give him room!

But you only watch,

terrified

the old consolations

will get him at last

like a fish

half-dead from flopping

and almost crawling

across the shingle

almost breathing

the raw, agonizing

air

till a wave

pulls it back blind into the triumphant

sea.

—Adrienne Rich

Table of Contents

Cover (#u418f149d-d638-5cb4-a872-e8042dec35a8)

Title Page (#u856a56de-f680-5d94-a313-fab96cf03384)

Dedication (#uad841fb6-086b-5715-8831-80c0faf3e5ba)

Epigraph (#ueb3d58e6-aba3-5b4d-a1b2-f5847f978f11)

Prologue (#ud82b3f49-61ad-5976-a008-bcf6a0770830)

Gualtiero Agnello (#ud6a29cda-5234-572d-a5fa-ab6b5b72ea26)

Part I: Art and Service (#ub9205368-68cd-54c0-98cf-56c423f63e52)

Chapter One: Annie Oh (#u16a956e9-e8cf-5b4c-99bc-668581a72b6e)

Chapter Two: Orion Oh (#ua31ec73a-3223-55f0-8890-5a3933f73f45)

Chapter Three: Annie Oh (#u16b42901-c6e9-55b0-a8ca-51d9c2466379)

Chapter Four: Orion Oh (#u45625717-ac06-5d44-87d5-8328ba200255)

Chapter Five: Annie Oh (#u1737ca23-76ba-5bc4-9ce5-bb68be268026)

Chapter Six: Orion Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven: Annie Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight: Orion Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine: Annie Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II: Mercy (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten: Ruth Fletcher (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III: Family (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven: Andrew Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve: Marissa Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen: Ariane Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen: Orion Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen: Andrew Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen: Orion Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen: Andrew Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen: Orion Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Part IV: A Wedding (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen: Kent Kelly (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty: Annie Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One: Kent Kelly (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two: Annie Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three: Kent Kelly (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four: Andrew Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five: Annie Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six: Andrew Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Part V: Three Years Later (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Orion Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Orion Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Orion Oh (#litres_trial_promo)

Gratitude (#litres_trial_promo)

A Note from Wally Lamb (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Wally Lamb (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_078ceb3f-62ee-58f4-b8f2-13413c89064f)

Rope-Skipping Girl (#ulink_078ceb3f-62ee-58f4-b8f2-13413c89064f)

Gualtiero Agnello (#ulink_0608a057-1381-5c72-b62e-a500a60b1bce)

August 2009

I understand there was some controversy about the coroner’s ruling concerning Josephus Jones’s death. What do you think, Mr. Agnello? Did he die accidentally or was he murdered?”

“Murdered? I can’t really say for sure, Miss Arnofsky, but I have my suspicions. The black community was convinced that’s what it was. Two Negro brothers living down at that cottage with a white woman? That would have been intolerable for some people back then.”

“White people, you mean.”

“Yes, that’s right. When I got the job as director of the Statler Museum and moved my family to Three Rivers, I remember being surprised by the rumors that a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan was active here. And it’s always seemed unlikely to me that Joe Jones would have tripped and fallen headfirst into a narrow well that he would have been very much aware of. A well that he would have drawn water from, after all. But if a crime had been committed, it was never investigated as such. So who’s to say? The only thing I was sure of was that Joe was a uniquely talented painter. Unfortunately, I was the only one at the time who could see that. Of course now, long after his death, the art world has caught up with his brilliance and made him highly collectible. It’s sad—tragic, really. There’s no telling what he might have achieved if he had lived into his forties and fifties. But that was not to be.”

I’m upstairs in my studio, talking to this curly-haired, pear-shaped Patrice Arnofsky. When she called last week, she’d explained that she was a writer for an occasional series which profiled the state’s prominent artists in Connecticut magazine. They had already run stories on Sol LeWitt, Paul Cadmus, and the illustrator Wendell Minor, she said. Now she’d been assigned a posthumous profile of Josephus Jones in conjunction with a show that was opening at the American Folk Art Museum. “I understand that you were the only curator in his lifetime to have awarded him a show of his work,” she’d said. I’d told her that was correct. Agreed to talk with her about my remembrances of Joe. And so, a week later, here we are.

Miss Arnofsky checks the little tape recorder she’s brought along to the interview and asks me how I met Josephus Jones.

“I first laid eyes on Joe in the spring of 1957 when he appeared at the opening of an exhibition I had mounted called ‘Nineteenth-Century Maritime New England.’ It was a pretentious title for a self-congratulatory concept—a show that had been commissioned by a wealthy Three Rivers collector of maritime art whose grandfather had made millions in oceanic shipping. He had compensated the museum quite generously for my curatorial work, but it had bored me to tears to hang that show: all those paintings of frigates, brigs, and steamships at sea, all that glorification of war and money.

“On the afternoon of the opening, I was making small talk with Marietta Colson, president of the Friends of the Statler, when she stopped midconversation and looked over my shoulder. A frown came over her face. ‘Well, well, what have we here?’ she said. ‘Trouble?’ My eyes followed hers to the far end of the gallery, and there was Jones. Among the well-heeled, silver-haired patrons who had come to the opening, he was an anomaly with his mahogany skin and flattened nose, his powerful laborer’s build and laborer’s overalls.

“We watched him, Marietta and I, as he wandered from painting to painting. He was carrying a large cardboard box in front of him, and perhaps that was why he reminded me of the gift-bearing Abyssinian king immortalized in The Adoration of the Magi—not the famous Gentile da Fabriano painting but the later one by Albrecht Dürer, who, to splendid effect, had incorporated the classicism of the Italian Renaissance in his northern European art. Do you know that work?”

“I know Dürer, but not that painting specifically. But go on.”

“Well, throughout the gallery, conversations stopped and heads turned toward Josephus. ‘I hope there’s nothing menacing in that box he’s holding,’ Marietta said. ‘Do you think we should notify the police?’ I shook my head and walked toward him.

“He was standing before a large Caulkins oil of La Amistad, the schooner that had transported African slaves to Cuba. The painting depicted the slaves’ revolt against their captors. ‘Welcome,’ I said. ‘You have a good eye. This is the best painting in the show.’

“He told me he liked pictures that told a story. ‘Ah yes, narrative paintings,’ I said. ‘I’m drawn to them, too.’ His bushy hair and eyebrows were gray with cement dust, and the bib of his overalls was streaked with dirt and stained with paint. He had trouble making eye contact. Why had he come?

“‘I paint pictures, too,’ he said. ‘I can’t help it.’ I knew what he meant, of course. Had I not been painting for decades, more involuntarily than voluntarily at times? ‘I’m Gualtiero Agnello, the director of this museum,’ I said, holding out my hand. ‘And you are?’

“He told me his name. Placed his box on the floor and shook my hand. His was twice the size of mine, and as rough as sandpaper. ‘You the one they told me to come and see,’ he said. He didn’t identify who ‘they’ were and I didn’t ask. He picked up his box and held it at arm’s length, expecting me to take it. ‘These are some of my pictures. You want to look at them?’

“I told him this wasn’t really a convenient time. Could he come back some day the following week? He shook his head. He worked, he said. He could leave them here. I was hesitant, suspecting that he had no more talent than the Sunday painters who often contacted me—dowagers and dilettantes, for the most part, who became huffy when I failed to validate their assumptions of artistic genius. I didn’t want to be the bearer of bad news. Still, I could tell that it had cost him something to come here, and I didn’t want to disappoint him either. ‘Tell you what,’ I said. ‘You see that table over there where the punch bowl is? Slide your box underneath it. I’ll look at your work when I have a chance and get back to you. Do you have a telephone?’

“He shook his head. ‘But you can call my boss when you ready to talk, and he can tell me. I don’t know his number, but he in the phone book. Mr. Angus Skloot.’

“‘The building contractor?’ He nodded. The Skloots were generous donors to the museum, and Mrs. Skloot was a member of the Friends. ‘Okay then, I’ll be in touch.’ He thanked me for my time. I told him to help himself to punch and cookies, but when he looked over at the refreshments table and saw several of the other attendees staring back at him, he shook his head.

“He stayed for a little while longer, repelling the crowd wherever he wandered, as if he were Moses parting the Red Sea, but unable to resist the art he would stop before and study. As I watched him walk finally toward the exit, Marietta approached me. ‘I’m dying of curiosity, Gualtiero,’ she said, her mouth screwed up into a sardonic half-grin. ‘Who’s your new colored friend?’

“I stared at her without answering, waiting for her to stop smirking. When she did, I said, ‘He’s an artist. Isn’t that the reason the Friends of the Statler exists? To support the artists of our community?’ She nodded curtly, pivoted, and walked away.

“The opening ended at five P.M. I escorted the last of the guests to the door. The caterers packed up the punch bowl and cookie trays, folded the tablecloth, and moved the table they’d used back to its proper place at the entrance to the exhibit. The janitors stacked the folding chairs and began to sweep. And there it was, by itself in the middle of the floor: Jones’s box. I carried it upstairs to my office. Then I put my coat on, went downstairs, and locked up the building on my way out. For the rest of that weekend, I forgot all about Josephus Jones.

“But on Monday morning, there it was again: the box. I opened it, removed Jones’s two dozen or so small paintings, and spread them across my work counter. He’d used what looked and smelled like enamel house paint. Two of the works had been painted on plywood, another on Masonite board. The rest were on cardboard. The tears in my eyes blurred what was before me.”

“And what was before you?” Miss Arnofsky asks. “Can you describe what you saw?”

“Well, he had no understanding of perspective; that was immediately apparent. Many of the figures that populated his paintings were out of proportion. He knew nothing about the technique of chiaroscuro; there was no play between shadow and light in any of his samples. Nevertheless, he had an intuitive sense of design and a wonderful feeling for vivid color. His subject matter—cowboys and Indians, jugglers and jungle animals, tumbling waterfalls, women naked or barely clothed—possessed all the characteristics of the modern primitive. Yet each gave evidence of a unique vision. And Josephus Jones was indeed a narrative painter; his pictures suggested stories that celebrated the rustic life but warned of sinister forces that lurked in the bushes and behind the trees.

“I called Angus Skloot, who told me where Joe was working that day. And so I carried his box of paintings out to my car and drove to the building site. Joe introduced me to his brother, Rufus; the two were building a massive stone fireplace inside the unfinished house. I suggested we talk outside so that I could deliver the good news about his artistic talent.

“He must have been thrilled to receive it,” my guest says.

“No, quite the contrary. He was unsurprised, unsmiling; it was as if he already knew what I had to tell him. I asked him how long he’d been painting. About three years, he said. Told me he’d begun the day he awoke from a dream about a beautiful naked woman riding on the back of a lion. He had grabbed a carpenter’s pencil and a piece of wood, he said, so that he could draw his dream before it faded away like fog. He wanted to remember it, but he wasn’t sure why. All that day, he said, he thought about the woman astride the lion. And so, at the end of his workday, he got permission from Mr. Skloot to take some of the almost-empty cans from the paint shed. Then he’d gone home and painted what he had first dreamt and then sketched out. He said he had been painting ever since. I handed him back his box of paintings and he placed it on the ground between us. ‘Tell me about yourself,’ I said. He looked suspicious, I remember. Asked me what it was I wanted to know. ‘Whatever you want to tell me,’ I said.”

“And what did he want to tell you?” Miss Arnofsky asks. “I realize that this was years ago, but it would be helpful to me if you can recall it as accurately as possible.”

It’s strange what happens next. When a painting I’m working on becomes my singular focus—when I am “in the zone,” as I’ve heard people put it—a trancelike state will sometimes overtake me. And now it’s happening not with my art but with my memory. Seated across from me, Miss Arnofsky fades away and the past becomes more alive than the present …

Joe scuffs his work boot against the ground and takes his time thinking about it. “Well, my granddaddy on my daddy’s side was a slave on a Virginia tobacco farm and my grams was a free woman.” After the emancipation, they moved up to Chicago and his grandfather got work in the stockyards. His mother’s people were third-generation Chicagoans, he says. “Mama washed rich ladies’ hair during the week at a fancy hotel beauty parlor downtown, and on weekends she preached in the colored church. My daddy worked in the stockyards at first, like his daddy did. But sledgehammerin’ cows between the eyes to get them ready for slaughter give him the heebie-jeebies, so he quit. Got work at a brickyard and become a mason—a damn good one, too. When me and Rufus was thirteen and fourteen, Daddy started bringing us along on jobs, and that was how we learnt to work with stone and mortar ourselfs.” His father was a better mason than he is, Joe says, but Rufus is better than both of them. “He a artist uses a trowel and ce-ment instead of a paintbrush is what Mr. Skloot told him,” Joe says, smiling broadly. “And thass about right, too.”

I ask him how long he’s lived in Three Rivers. Since 1953, he says, and when I tell him that was the year my family and I moved here, too, his eyes widen, then slowly lock onto mine. He nods knowingly, as if our having arrived in Three Rivers at the same time is more about fate than coincidence.

Both of his parents had passed by then, he tells me, and Rufus had just gotten out of the navy. He urged Joe to come east because he had a plan. They would get good jobs at the shipyard in Groton, helping to build America’s first nuclear submarine, the U.S.S. Nautilus. But the shipbuilders had shied away from hiring coloreds, fearing repercussions and race baiting from their white workers. “So we took whatever jobs we could find. Worked tobacco up in Hartford, worked at a sawmill, dug graves. We took masonry jobs when we could find them, which was just this side of never. The luckiest day of our life was the day Mr. Skloot come to visit his sister’s stone at the cemetery up in Willimantic,” he says. “Rufus and me was digging a grave two plots down, and he come over and the three of us got to talking. Mr. Skloot’s face lit up when we told him we was gravediggers for right now but masons, mostly. He said he’d just fired his mason for being drunk on the job. Well, sir, by the time he got back in that big ole black Oldsmobile of his and drove away, we had us jobs with Skloot Builders. We was spoze to be on trial for a month so Mr. Skloot could see what kind of work we done, and if we was hard workers and dependable, and didn’t get liquored up. But we got hired permanent after just the first week because Mr. Skloot liked what he seed us do—well, Rufus’s work more than mines, but mines, too.”

Mr. Skloot is the best boss he’s ever had, Joe says. When I ask him why, he says, “Because he pay good and he kind. Lets us live out back on his property, and he don’t even care that Rufus got hisself a white wife. Rufe married his gal when he was stationed over in Europe and brung her over here after we was working steady. She Dutch.” Joe touches his work boot to the box at his feet. “I got other paintings at the house, you know. Lots of ’em. If you like these ones, maybe you want to see those ones, too.” I tell him I do and arrange to meet him at his home at six o’clock that same evening.

The house is a small cottage at the back of the Skloots’ property. Following Joe’s instructions, I drive down the Skloots’ driveway, then inch my car over a rutted path out back until I get to a brook. I park and get out, then cross the brook by way of two bowed two-by-six planks that have been placed over it. A thin white woman—Joe’s brother’s Dutch wife, I figure—is outside, hanging clothes in just her slip. When I ask her if Josephus is home, she sticks out her thumb and points it toward the door. Before I can knock, it swings open and Jones invites me in.

The place is filthy. It reeks of stale cooking odors and cat urine, and there is clutter everywhere. A fat calico cat is asleep on the kitchen table amidst dirty dishes, old magazines, and an ash tray brimming with stubbed-out cigarettes. The floor beneath my shoes feels gritty. Josephus’s paintings are everywhere: stacked against walls and windowsills, atop a refrigerator whose door is kept shut with electrical tape. There are more paintings scattered across the mattress on the floor and on the dropped-down Murphy bed. “What’s this one called?” I ask Joe, pointing to a female figure in a two-piece bathing suit standing in a field of morning glories, parakeets alighting on her head and outstretched arms.

“That one there? Thass Parakeet Girl.” When I pick it up for a closer look, the roaches hiding beneath it scuttle for cover.

But housekeeping is beside the point. I look closely at every work he shows me, overwhelmed by both his output and his raw talent. I’m there for hours. Some of his paintings are more successful than others, of course, but even the lesser efforts display an exotic, unschooled charm and that bold use of color. Before I leave, I offer him a show at the Statler. He accepts. When I get home, I tell my wife that I may have just discovered a major new talent.

But “Josephus Jones: An American Original” is a flop. The local paper, which is usually supportive of our museum shows, declines to publish either a feature story or a review. At the opening, instead of the usual two hundred or so, fewer than twenty people attend. Not even Angus and Ethel Skloot have come; they are on holiday in Florida. It’s painful to watch the Jones brothers scuff the toes of their shined shoes against the gallery’s hardwood floor and eye the entranceway with fading hope. Both have purchased sharp double-breasted suits for this special occasion, and Rufus’s Dutch-born wife has apparently bought new clothes, too: a sparkly, low-cut cocktail frock more suitable for an evening at a New York supper club than a Sunday afternoon art opening in staid Three Rivers, Connecticut. Worse yet, she has neglected to remove the tag from her dress, and I have to instruct my secretary, Miss Sheflott, to go upstairs to her desk, retrieve her scissors, and discreetly escort young Mrs. Jones out into the foyer for the purpose of clipping her tag. Later, Miss Sheflott tells me she tucked the tag inside the dress rather than removing it. Mrs. Jones has confided that she can’t afford it and is planning to return it to the LaFrance Shop on Monday.

In the days that follow, there are complaints about the show’s prevalence of female nudity. Three members of the Friends cancel their memberships in protest. In the six weeks the show is up, the number of visitors is dismally low—our worst attendance ever. I’ve penned personal letters to several influential New York art dealers and critics, inviting them to discover Jones. “He is a painter of events commonplace and exotic that are shot through with an underlying sense of anxiety,” I have written. “His compositions are rich with surprises, some joyful, some sinister. In my opinion, he stands shoulder to shoulder with other American primitive painters, from Grandma Moses to his Negro brethren, Jacob Lawrence and Horace Pippin, and the breakthrough artists of the Harlem Renaissance.” But none of those busy New Yorkers to whom I’ve written has had the courtesy even to reply, let alone trek the three hours to our little museum to see Josephus’s work for themselves.

The show ends. We keep in touch from time to time, Joe and I. I encourage him, critique the new work he sometimes brings by. I’m sad to learn from Joe that his brother Rufus’s wife has left him, and that Rufus has taken it badly—has fallen in with a bad crowd and begun using heroin. “Mr. Skloot let him go after he found out he be messin’ wiff the devil’s drug,” Joe says. “Booted him out of the house out back, too. I been saving up some to send Rufe to one of them sanctoriums to get hisself clean, but they cost more money than I gots. If I could sell some paintings here and there, I could do it, but ain’t no one like them enough to buy any.” I try several more times to interest my New York connections in Joe’s work—alas, to no avail. Eventually, he stops coming around to the museum and we fall out of touch.

But in the summer of 1959, during Three Rivers’s celebration of its three hundredth anniversary, I am asked to judge the art show on the final day of festivities. It’s a big show; more than three hundred artists, accomplished and amateurish, have submitted work for consideration. Most have chosen “pretty” subject matter: quaint covered bridges, romanticized portraits of rosy-cheeked children, and the inevitable still lifes of flowers and fruit. As I wander the grounds, looking for something to which I can affix a “best in show” ribbon and still sleep that night, I come upon Josephus’s work at the south end of the festival grounds. Delighted and relieved, I scan what I have previously admired: Parakeet Girl, Jesse James and His Wife, his pictures of pinup girls and fishermen midstream, ukulele players and circus curiosities. One theme seems to prevail in Jones’s work: predators—lions and tigers, lynxes and leopards—attacking or about to attack their prey. Then, among these familiar paintings, I see a spectacular new one—twice as large and twice as ambitious as the others. At the center of the composition stands the Tree of Life, lush and fecund. Beneath it are a pale, naked Adam and Eve. The latter figure is reminiscent of the prepubescent Eves of Van Leyden, the sixteenth-century Dutch master. Adam, though his skin is gray rather than brown or black, bears the face of Josephus Jones himself. The benign members of the animal kingdom who surround the two human figures seem almost to smile. But trouble lurks, in the form of the treacherous serpent hanging from the tree. Joe has depicted a moment in time. Adam reaches for the forbidden fruit which Eve is about to pluck. It will be the fateful act of self-will that will banish them both from the garden. Innocence is about to be lost, and we humans, forever after, will be stained with our forebears’ original sin. In Adam and Eve, Jones is once again exploring the theme of the predator and the prey, but he has done so in a more subtle and masterly way. Adam and Eve is a leap forward—a stellar achievement, and I am elated to hang the “best in show” blue ribbon next to it. The festival gates swing open to the public at 9:00 A.M. As I exit, they push past me, eager not so much to view the art, I suspect, as to fill their bellies with the pancakes that are being cooked and served inside the tent by a large black woman gotten up to look like Aunt Jemima. I admire the organizers’ cunning. If you want people to flock to art, lure them with pancakes.

Later, I’m informed that the festival committee was unhappy with my selection, and I read in the newspaper the following day that an irate art show attendee rushed Jones’s Adam and Eve, intent on destroying it, and that this would-be art critic had scuffled with its creator. This news delights me! Isn’t that art’s purpose, after all? To engage and, if necessary, disturb the beholder? To upset the apple cart and challenge the status quo? Was that not what the great Michelangelo did as he lay on his back, painting political satire onto the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel? Haven’t artists, from that great sixteenth-century genius to Manet and Rivera, outraged the public and forced them to think? Now that his art has been attacked, Josephus has joined the ranks of an illustrious fellowship.

Several weeks later, I am in my office at the museum, working on the budget for the coming year and half-listening to the radio. A novelty song is playing—one that mocks “the troubles” between the Irish and the Brits.

You’d never think they go together, but they certainly do

The combination of English muffins and Irish stew

I chuckle at the words, thinking, well, if paintings can make political statements, then why can’t silly popular songs? But I stop cold when the music ends and the news comes on. The announcer says that thirty-nine-year-old Josephus Jones, a local construction worker, has died accidentally—that he has tripped and fallen into a well behind his residence and drowned. I sit there, stunned and sickened. A promising artist has been cut down by fate just as he was hitting his stride. Unable to work, I put on my coat, walk out of my office, and drive home.

I go to his funeral service at the colored church. The Negro community has come out in impressive numbers to sing and wail and shout out their grief about Joe Jones’s premature demise, but I am only one of four Caucasians who have come to mourn him; the other two are Angus and Ethel Skloot and a distraught young woman who looks familiar but whom I cannot, at first, place. But halfway through the service, it dawns on me who she is: the Eve of Josephus’s painting, reaching for the forbidden fruit that hangs just below the malevolent serpent. Joe’s brother Rufus is one of the pallbearers, but he looks disheveled and dazed, every bit the drug addict that Joe said he had become. The snake, I see, has bitten him, too.

None of the mourners who orate at the service, or who later gossip at “the feed” downstairs after the “churchifying,” mentions Josephus’s relationship to art. But I hear, over and over, their rejection of Coroner McKee’s finding that Joe died accidentally. “A skull fracture and a six-inch gash on his forehead?” one skeptic stands and says. She is a loud, angry woman in an elaborate hat who looks like she tips the scales between two fifty and three hundred pounds, and as she speaks I realize that she is the same woman who played the part of Aunt Jemima at the pancake breakfast. “A six-foot man just ups and falls headfirst into a well that’s seven foot deep and twenty inches across? If that was an accident, then I’ll eat this hat I’m wearing, feathers and all,” she declares. “That’s why we got to keep fighting the good fight in the name of Jesus Christ Almighty! To get Brother Josephus some justice and right what’s wrong in this sorry world and this sorry town!” From various places around the room, people call out in agreement. “Mm-hmm, that’s right!”

“You tell ’em, Bertha!”

“Amen, sister!”

From the other side of the room, I hear a man’s tortured sobs. It breaks my heart when I see that it is Joe’s afflicted brother, Rufus …

“How sad,” Miss Arnofsky says, and her comment returns me from the past to the present, from the basement of the Negro church back to my studio.

“Yes. Yes, it was. Poor Rufus died not long after that, in the flood.”

“The flood?”

I nod. “A dam gave way in the northern part of town, and the water it had been holding back took the path of least resistance, rushing toward the center of town and destroying a lot of the property in its path. Several people were killed, Rufus Jones included. The paper said he had been living in an abandoned car down by the river.”

“When was that?”

“Nineteen sixty-two? Sixty-three, maybe?”

“And so sad, too, that Josephus never knew what a success he would eventually become. But at least in his lifetime, he had your advocacy.”

“Yes, I was able to give him that much at least. But it went both ways. Joe gave me something, too.”

“What do you mean?”

I pause before answering her, thinking about how to put it. “Well, Miss Arnofsky, many years have passed since the morning I hung that blue ribbon next to Joe’s Adam and Eve. I’ve judged many juried shows, large and small, always asking myself just what is the function of art? What is its value? Is it about form and composition? Uniqueness of vision? The relationship between the painter and the painting? The painting and the viewer? Sometimes I’ll award the top prize to a formalist, sometimes to an expressionist or an abstract artist. Less often but occasionally I will select an artist whose work is representational. But whenever and wherever possible, I celebrate art that shakes complacency by the shoulders and shouts, ‘Wake up!’ Not always, certainly, but often enough, this has been the work of outsiders rather than those who have been academically trained—artists who, unlike myself, are unschooled as to the subtleties of technique but who create startling work nonetheless.” My guest nods in agreement, and I laugh. “And now, if you’ll excuse me,” I tell her, “I have to climb down from my soapbox and go downstairs and use the toilet.”

“Of course,” she says. I rise from my chair and stand, my ninety-four-year-old knees protesting as I do. Miss Arnofsky asks if she might have a look around at my work while she’s waiting, and I tell her to be my guest.

When I return a few minutes later, she is standing in front of the shelf by the window, looking at a shadow box collage a young artist gave me years ago. “It’s called The Dancing Scissors,” I tell her. “The artist is someone I awarded a ‘best in show’ prize to years ago, and she gave it to me as a gift. She’s become quite celebrated since then.”

“I recognize the style,” she says. “It’s an Annie Oh, isn’t it?”

“Yes, that’s right. You know her work?”

She nods. “I did a profile piece on her for our magazine when she was just starting out. It was called ‘Annie Oh’s Angry Art.’ She was very shy, almost apologetic about her work. But what struck me was the discrepancy between her demeanor and the undercurrent of rage in her art.”

“Yes, I suppose that was what drew me to it as well: the silent scream of a woman tethered to the conventional roles of mother and wife and longing to break free. I predicted great things for Annie back then, and I’m delighted that that has come to pass. We’ve stayed in touch, she and I. As a matter of fact, she’s being remarried next month, and I’m going to her wedding.”

“Oh, how nice. If you think of it, please tell her I said hello, and that I wish her and her new husband all the best.”

“Of course, of course. But I shall have to extend your greeting to Annie and her wife. She’s marrying the owner of the gallery that represents her work.”

“Aha,” Miss Arnofsky says. “Now tell me about the other paintings here in your studio. These are your works?” I nod.

She wanders the studio, looking through the stacks of my paintings leaning against the walls, both the ones that have returned from various shows and those that have yet to leave my work space. Standing before my easel, she smiles at my half-finished rope-skipping girl. “I so admire that you’re still at it every day,” she says. “I see this is a recurring subject for you.”

“Yes, that’s right. Little Fanny and her jump rope. I’ve painted her hundreds of times.” I explain to my guest that it was my good fortune to have received a scholarship to the school at the Art Institute of Chicago when I was sixteen years old, and how my training there helped to shape my artistic vision. “At first I merely imitated the styles of the painters I most admired. The impressionists and expressionists, the pointillists. But little by little, I began developing a style of my own, which one of my teachers described in his evaluation as ‘boldly modern with a freshness of vision.’ I don’t mean to boast, but I began to be recognized as one of the three most promising students at the school, the others being my friends Antonio Orsini, who came from the Bronx and loved the New York Yankees more that life itself, and Norma Kaszuba, an affable Texan who wore cowgirl boots, smoked cigars, and swore like a man.”

“A woman before her time,” Miss Arnofsky notes. “But tell me about your jump-roping girl.”

“Well, I spotted her one afternoon when Norma, Antonio, and I were eating our lunch in Grant Park. She was just a nameless little Negro girl in a shapeless gray dress, skipping rope and singing happily to herself. Her wiry hair was in plaits. Her face was turned up toward the sun in joyful innocence. As I recall, my friends and I had been arguing about whether Roosevelt, the president-elect, would prove to be a savior or a scoundrel. And as the others’ voices faded away, I pulled a pencil from my pocket and, on the oily paper in which my sopressata sandwich had been wrapped, began sketching the child. Back at the school that afternoon, I drew the girl over and over, and in the days that followed I began painting her in gouache and oils, in primary colors and pastels and monochromatic shades of green and gray. It was as if that guileless child had bewitched me! I gave her a name, Fanny, and came to think of her as my muse. For my final project, I submitted a series of sixteen works, collectively titled Girl Skipping Rope. On graduation day, I held my breath as one of the Institute’s capped-and-gowned dignitaries announced, ‘And this year’s top prize is awarded to … Gualtiero Agnello!’ It was the thrill of a lifetime. And as you can see, capturing Fanny has become a lifelong obsession.”

“Fascinating,” my guest says. “You know, I Googled you before I came over here today. You’ve had shows at several major museums, haven’t you?”

“Oh, yes. MoMA, the Corcoran, the Whitney. One of my paintings was purchased for the Smithsonian’s permanent collection a while back—a study of my little rope-jumping angel over there.”

“Wikipedia said you were born in Italy.”

“Yes, that’s right. In the city of Siena.”

“Ah, Tuscany! Well, that was certainly fortuitous. So many great artists came from that region. Who would you identify as your early influences?”

“Well, my parents and I moved to America when I was quite young, so none of the masters. I’d have to say I was drawn to art by my father.”

“He was an artist?”

“Not by trade, no. He was a tailor. But among my earliest and fondest memories is having sat long ago on his lap at a table outside the Piazza del Campo, watching, wide-eyed, as Papa’s pencil turned blank paper into playful cartoon animals for me. His ability to do so had seemed magical to the little boy I was. But sadly, my parents fell on hard times after my father’s tailor shop was burned to the ground by the vengeful husband of his mistress. It was Papa’s brother, my Uncle Nunzio, who came to our rescue. He assured my father that Manhattan has thousands of businessmen and they all needed suits. He sent money, too—enough American dollars which, converted to lira, allowed Papa to purchase three passages to New York. And so we left Siena, boarded a ship at the port in Livorno, and traveled across the ocean. I still remember how frightened I was during that long voyage.”

“Frightened? Why?”

“Because I thought we would never be free of that endless, shapeless gray water—that we were doomed to sail the sea forever. But twelve days after we left Livorno, we passed La Statua della Libertà and arrived on American soil.”

“And you were how old?”

“Eight. Of course, at that age, I could only understand bits and pieces of the reasons for our uprooting. But years later, after my own sexual desires had awakened, Papa confided to me that he had not wished to be unfaithful to my mother, but that his inamorata, Valentina, had a body by Botticelli and hair so flaming red that she might have stepped out of a painting by Titian. You see, my father was a clothier by trade, but his passione was art. He was like Josephus Jones in that respect. He’d had no formal training, but he had a natural talent and an undeniable urge to draw. He was seldom without his pencil and portfolio of onionskin paper. ‘A gift from God,’ my mother once called her husband’s artistic talent, although she would later describe it as ‘my Giuseppe’s curse.’”

“And why was that?”

“Because it unhinged him. Made him crazy. That’s often the case, of course—that creation and madness begin to dance with each other.”

“Like Van Gogh.”

“Yes, Van Gogh and many others. Painters, writers, musicians.”

She nods. Sighs. “So your family settled in New York?”

“Lower Manhattan, yes. We lived above Uncle Nunzio’s grocery market in a four-story tenement on Spring Street. Nunzio knew someone who knew someone, and soon my father was altering men’s suits at Macy’s Department Store on Herald Square. And while Papa was measuring inseams, sewing shoulder pads into suit coats, and letting out the trousers of fat-bellied businessmen, I was mastering proper English in the classrooms of the Catholic Sisters of the Poor Clares and learning broken English at Uncle Nunzio’s grocery market, where I worked after school and every Saturday. In warm weather, my job was to sell roasted peanuts from the barrel outside on the sidewalk. During the winter months, I was brought inside to wait on the customers.” I chuckle as I recall the kerchiefed nonnas who came by each day to shop for their family’s dinner and haggle over the prices of fruit and vegetables. Cagey Siciliani for the most part, who would first bruise the fruit they had selected and then demand a reduced price because the fruit was bruised. “At school, my teacher, Sister Agatha, took a shine to me and, because she thought I would make a good priest, urged me to pursue the sacrament of Holy Orders. But I was my father’s son on two counts: first, when I was in the eighth grade, I surrendered my virginity to a plump ‘older woman’ of sixteen who was fond of roasted peanuts. And second, I loved to draw. Seated on a stool next to my peanut barrel, I began sketching the Packards and roadsters parked along Spring Street, the passersby rich and poor and the fluttering garments hanging from clotheslines, the birds who flew in the sky and the pigeons who waddled along the sidewalk, pecking away at morsels. I filled sketchbook after sketchbook, eager to show Papa my latest drawings when he returned home from his day of tailoring. My father smiled very little back then, but he beamed whenever he looked at my pictures.”

“Like father, like son,” she says.

“Well, yes and no. Papa was unschooled, as I said. But when I was fifteen, one of my drawings won a prize: art lessons. And so each Saturday morning, freed from my job at Uncle Nunzio’s, I would ride my bicycle up Fifth Avenue to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where I would receive instruction from a German painter named Victorious von Schlippe. Like Uncle Nunzio, Mr. von Schlippe knew people who knew people, and the following year, at the age of sixteen, I was offered the scholarship at the Art Institute.”

“Your parents must have been very proud of you,” Miss Arnofsky says.

“My father was, yes. But Mama was against my going. She begged me to stay in New York—to find and marry a nice girl from the Old Country and give her grandchildren. Papa, on the other hand, urged me to go and learn whatever Chicago could teach me. I remember the tears in his eyes the morning he saw me off at Grand Central Station, especially after I unfolded the sheet of paper I’d slipped into my pocket when I’d packed the night before. ‘Look what I’m bringing, Papa,’ I said. He stood there, holding in his shaking hands one of the cartoon drawings he had made for me years before. Then he handed it back to me, blew his nose, and told me I’d better board the train before it left without me. And so, without daring to look back at him, I did.

“And oh, I loved the Windy City! Its crisp autumn weather, its warm and friendly people. I loved my classes, too, and was a sponge, absorbing whatever my instructors could teach me. On Sunday afternoons, it became my habit to write long letters to my parents about my exciting new life. But as autumn turned into winter, Mama’s letters back to me began to describe the strange obsession that had overtaken my father. Papa claimed that Catherine of Siena, Italy’s patron saint, had appeared to him in a vision, commanding him, for the edification of Italian Catholics the world over, to illustrate the story of her life: her service to the sick during the Black Death; her campaign to have the papacy returned from Avignon to Rome; her receiving of the stigmata. It was a terrible thing to witness, Mama wrote: a husband’s strange decline into madness.

“That Christmas, unable to afford the trip back to New York, I stayed in Chicago and sent my parents a gift box of candied fruit, sugared nuts, and nougats. Presents arrived for me as well. Mama had sent me three pairs of socks and a week’s supply of woolen underwear. Papa’s gift arrived in a long cardboard tube, and when I opened the end and uncurled the onionskin paper within, there was his charcoal rendering of the mystical marriage of Saint Catherine to Jesus Christ. The lines of the drawing were as frenzied and driven as the brushstrokes of the great Van Gogh, and the paper had several tears where he’d pressed down too hard with his pencil. I pinned Papa’s present to the wall above my bed, next to the fanciful drawing he had made for me when I was a little boy, and, looking from one to the other, lamented. If fate had been kinder to my father, I thought, he might have left New York, traveled west to California, and found work with the great Walt Disney instead of in a windowless back room at Macy’s gentlemen’s department. But as the people of the Old Country say, Il destino mischia le carte, ma siamo noi a giocare la partita. Destiny shuffles the cards, but we are the ones who must play the game.”

“That could just as well be a Yiddish proverb,” Miss Arnofsky says. “But destiny has certainly been kinder to you than it was to your father. A successful painter, the director of a museum.”

I nod. Smile at my guest. “Overseeing the Statler’s collection and hanging shows in its gallery hall is what paid our bills. But painting has always been my primary calling.”

“And there’s ample proof of that,” she says, scanning the room. She asks if I have children. One son, I tell her. Giuseppe. Joseph. “And has he followed in your footsteps?”

“As an artist? In a way, I suppose. He works in television out in Hollywood. Directs one of the daytime soap operas. And that calls for a kind of artistic style, too, of course. Television is so much about the visual.”

“Do you see him very often?”

“Not as often as I’d like. But I’ll see him next weekend. He has to be in New York on business, and so he’s coming up for the weekend. In fact, he’s bringing me to Annie Oh’s wedding.”

“Sounds nice. And you’re a widower?”

“Yes, my Anja died in 1989. Heart failure. One day she was here, the next she was gone.”

“And since then? Any other women in your life?”

“No, no. I suppose you could say that in old age, my work has become my wife. Or maybe this was always so.”

“Two long and happy marriages then,” Miss Arnofsky says.

I nod. “Long, happy, and somewhat mysterious.” My guest cocks her head, waiting for me to explain. “One’s wife, one’s art: you can never know either fully. After Anja died, I read her diaries and learned things about her I had never known. That she wrote verse—lovely little poems about her village back in Poland. And that once upon a time she had loved a boy in her village named Stanislaw.”

“And your paintings? They keep secrets, too?”

“In a way, yes. Sometimes I’ll work on a composition for weeks—months, even—without knowing what it is I’m searching for. Or for that matter, after I’ve finished it, what finally has been resolved. After all these years, I still can’t fully explain the process. The way, when you are deeply involved in a composition, everything else in the room fades away—everything but the thing before you that is calling itself into existence. It’s as if the work on your canvas has a will of its own. When that happens, it can be quite exciting. But disturbing, too, when, as the painter, you are not in control of your painting.”

“Forgive me; I mean no disrespect. But the way you describe it, it sounds almost like you experience a form of temporary madness yourself.”

“Madness? Perhaps. Who’s to say?”

Miss Arnofsky points to The Dancing Scissors and says she recalls Annie Oh telling her something similar—that she began creating her collages and assemblages without really knowing why or how she was doing it.

“That was true of Joe Jones, too,” I tell her. “As I said before, he told me he had begun painting because he had to. That something was compelling him. All I know is that at such heightened moments of creativity, I feel as if my work is coming not so much from me as through me. From what source, I can’t say. The muse, maybe? My father’s spirit? Or who knows? It could even be that the hand of God is guiding my hand.”

“So your talent may be God-given? Is that what you’re saying?”

“Well, I’m afraid that sounds rather grandiose.”

“Quite the contrary,” she says. “I’m struck by your humility in the face of all you’ve accomplished.” For the next several seconds, we stare at each other, neither of us speaking. Then she smiles, closes her notebook, unplugs her tape recorder. “Well, Mr. Agnello, I shouldn’t take up any more of your time, but I can’t tell you how grateful I am. This has been wonderful.”

“I’m just relieved to see that you still have both of your ears. I was afraid I might have talked them off.” She laughs, says she could have listened to me for hours more. “Oh, perish the thought,” I say. She rises from her chair, tape machine in hand, and I tell her I’ll see her out.

“No, no. I can let myself out. You should get back to your work.”

I nod. We thank each other, shake hands. From the doorway of the studio, I watch her disappear down the stairs.

But I do not return to my work as I’d intended.

The sun and the conversation of the past hour have made me sleepy. When I close my eyes, the images I evoked for my guest play on in my head: Rufus Jones, bereft at his brother’s funeral … Papa’s cartoon drawings coming to life before me at the piazza with the Fountain of Gaia gurgling nearby, water spilling from the mouth of the stone wolf into the aquamarine pool … Annie Oh’s strange collages that day when I first came upon them. Suddenly, I remember something else about that day—something I had forgotten all about until this moment. I had been wavering about whether to give the top prize to Annie or to an abstract expressionist whose work was also quite impressive. But as I stood there vacillating, a gray-haired Negro appeared by my side—a man who looked eerily like an older version of Josephus Jones. It wasn’t Joe, of course; by then, he had been dead for years. “This one,” the man said, nodding at Annie’s work. It was as if somehow he had read my mind and intuited my indecision. And that had clinched it. The “best in show” prize was hers …

“Mr. Agnello? … Mr. Agnello?”

When I open my eyes, my housekeeper is standing before me. She says my lunch is ready. Do I want her to bring up a tray?

“No, no, Hilda. I’ll be down in a minute.” She nods. Leaves.

Half-asleep still, my eyes look around, then land on the unfinished painting resting against my easel. It confuses me. Why does Fanny have angel’s wings? When did I paint those? I rise and go to her and, on closer inspection, realize that her “wings” are only the clouds behind her … And yet, winged or not, she is my angel. Seventy-odd years have slipped by since I spotted her that day in Chicago, and yet she continues to skip rope in my mind and on my canvases, raising her dark, hopeful face to the sky, innocent of the depth of people’s cruelty toward “the other”—those who, for whatever reason, must swim against the tide instead of letting it carry them …

Well, that’s enough deep thinking for this old brain. My lunch is ready and I’m hungry. I get up, balance myself. On my way out the door, I turn back and face my easel. “I’m too tired to do you justice any more today, little one,” I tell Fanny. “But I’ll be back tomorrow morning. I’ll see you then.”

On the stairs, I remember that I still have to send back that response card. Let Annie know that Joe and I are coming to her wedding.

Part I (#ulink_dbc42560-a78a-5633-8bec-1d36c82bb3fc)

Art and Service (#ulink_dbc42560-a78a-5633-8bec-1d36c82bb3fc)

Chapter One (#ulink_d0e69de2-fca1-5619-9e3d-e87a6352ec47)

Annie Oh (#ulink_d0e69de2-fca1-5619-9e3d-e87a6352ec47)

Viveca’s wedding dress has a name: Gaia. It’s lovely. Layers of sea green silk chiffon, cap sleeves, an empire waist, an asymmetrical A-line skirt with the suggestion of a train. I forget the designer’s name; Ianni something. He’s someone Viveca knows from the Hellenic Fashion Designers Association. It arrived at the apartment from Athens yesterday, and Minnie has pressed it and hung it on the door of Viveca’s closet.

Gaia: I Googled it yesterday after Viveca’s dress arrived and wrote down what it said on an index card. It’s on the bureau. I pick it up and read.

After Chaos arose broad-breasted Gaia, the primordial goddess of the Earth and the everlasting foundation of the Olympian gods. She was first the mother of Uranus, the ancient Greek embodiment of heaven, and later his sexual mate. Among their children were the mountains, the seas, the Cyclopes, and the Hundred-Handed giants who aided Zeus in his successful battle against the Titans, whom Gaia had also birthed.

Chaos, incest, monsters, warring siblings: it’s a strange name for a wedding dress.

The three Vera Wang dresses Viveca had sent over for me to consider were delivered yesterday, too. (Vera is one of Viveca’s clients at the gallery.) There’s an ivory-colored dress, another that has a tinge of pink, a third that’s pearl gray. Minnie spread them across the bed in the guest bedroom, but after she went home, I carried them into our bedroom and hung them to the left of the Gaia. This morning when I woke up, they scared me. I thought for a split second that four women were standing over by the closet. Four brides—one in gorgeous green, three in off-white.

Viveca is abroad still. She went to Athens a week ago for a fitting but then decided to stay several more days to visit with an elderly aunt (her father’s surviving sister) and to finalize the details for our wedding trip to Mykonos. She called me from there last night. “Sweetheart, it’s the land of enchantment here. Have you looked at the pictures I e-mailed you?” I said I hadn’t—that I’d been more in the studio than at the apartment for the last several days, which was a lie. “Well, do,” she said. “Not that photographs can really capture it. In daylight, the Aegean is just dazzling, and at sunset it turns a beautiful cobalt blue. And the villa I’ve rented? Anna, it’s to die for! It sits high on a hill above town and there’s a panoramic view of the harbor and some of the other islands in the archipelago. The floors are white marble from a quarry in Paros, and there’s an oval pool, an indoor fountain, a terrace that looks out on a grape arbor that’s unbelievably lush and lovely.” Why a pool if the sea is right there? I wonder. “The houses here are sun bleached to the most pristine white, Anna, and there are hibiscus growing along the south side of the villa that, against that whiteness, are the most intense red you could ever imagine. I just can’t wait to share it all with you. You’ll see. This place is an artist’s dream.”

“I’ll bet it is,” I said. “For an artist who’s interested in capturing what’s pretty and picturesque. I’m not.”

“I know that, Anna. It’s what drew me to your work from the start.”

“It?” I said. “What’s ‘it’?”

There was a long pause before she answered me. “Well, it’s like I was telling that couple that bought those two pieces from your Pandora series. Your work looks people in the eye. It comforts the disturbed and disturbs the comfortable. But this will be a vacation, sweetheart. You work so hard. Mykonos is my gift to you, Anna. My gift to us. Four weeks surrounded by what’s lovely and life affirming at the start of our married life. Don’t we deserve that?”

The room went blurry with my tears. “I miss you,” I said.

“I miss you, too, Anna. I miss you, too.”

It’s not that I don’t want to be with her in Mykonos. But four whole weeks? In all the years I’ve been at it, I’ve never been away from my work that long. Well, to be fair, she’ll be away from her work, too. “It’s not a very savvy business decision,” she said when she told me she’d rented the villa for the entire month of October. “People will have awakened from their Hamptons comas by then, reengaged with the city, and be ready to buy. But I said to myself, ‘Viveca, the hell with commerce for once! Seize the day!’ I smiled and nodded when she said that, swallowing back my ambivalence instead of voicing it.

You do that for someone you love, right? Keep your mouth shut instead of opening it. Bend on the things that are bendable. This wedding, for instance. It’s Viveca who wants to make our union “official.” And where we’ll be married: I’ve had to bend on that, too. Okay, fine. I get it. Connecticut has legalized gay marriage and New York hasn’t. But why not book a place in some pretty little Gold Coast town closer to the city? Cos Cob or Darien? Why the town where Orion and I raised our kids? She’d wanted to surprise me, she said. Well, she’d achieved her objective, but it’s … awkward. It’s uncomfortable.

Okay then, Annie. If you have misgivings, why go through with it? Why not tell her you’ve had second thoughts? … I look up, look around our well-appointed apartment, and I see a part of the answer hanging on the wall in the hallway: the framed poster announcing the opening of my first show at viveca c. The headline, ANNIE OH: A SHOCK TO THE SYSTEM!, and beneath it, the full-color photo of my sculpture Birthings: the row of headless mannequins, their bloody legs spread wide, their wombs expelling serial killers. Speck, Bundy, Gacy. Monsters all.

My art comforts the disturbed and disturbs the comfortable: she’d put it better than I ever could have. It’s one of the reasons why I love Viveca. The fact that she not only promotes my work and sells it at prices I couldn’t have imagined, but that she also gets it. And yes, her apartment is as lovely as she is, and our lovemaking feels satisfying and safe. But for me that may be the foundation of our intimacy: the fact that she understands what my work attempts to do.

Orion never did. But then again, why would he have? I’d been so guarded all those years. A twenty-seven-year marriage of guardedness, based on nothing more than the fact that he was a man and, therefore, not to be trusted with the worst of my secrets.

But come on, Annie. You haven’t told Viveca your secrets either. Why is that? Because you’re afraid she might change her mind? Stop taking care of you? Be honest. Your own mother dies in the flood that night. Then your father drinks himself out of your life. And your foster parents were just stop-gaps. They fed you, clothed you, but never loved you. You wanted the real thing. Do you think it’s a coincidence that Orion and Viveca are the same age? That both your ex-husband and your wife-to-be are seven years older than you?

No, that’s irrelevant … Or is it? Is that the real reason why you married him? Why you’re marrying her? Because Little Orphan Annie still needs someone to take care of her?

I need to stop this. Stop being so hard on myself. I love Viveca. And I loved Orion, too … But why? Because he had taken me under his wing? Because for the first time in my life, intimacy with a man was enjoyable? Safe? Maybe not as safe as it feels with Viveca, or as wild as it had been with Priscilla. But pleasurable enough. And very pleasurable for him. It made me a little envious, sometimes. The intensity of his …

No. I wanted to give him pleasure. But his pleasure had a price.

No, that’s not fair. It had been a joint decision. I had stopped using my diaphragm because we both wanted a child. But when my pregnancy became a fact instead of a desire, I was suddenly seized with fear. What if I wasn’t up to the job of motherhood? What if I miscarried again like I had that time when I was seventeen? I had never told Orion about my first pregnancy, and I held off for a week or more before I told him about this one. The night I finally did tell him, Orion promised me that he was going to be the best father he could—the opposite of his own absentee father. We cried together, and I let him assume that mine were happy tears, the same as his. They weren’t. But little by little my fear subsided, and I began to feel happy. Excited. Until I had that ultrasound. When I learned we were having twins, I got scared all over again. And when, in the delivery room, it looked like we might lose Andrew, I was terrified …

Still, I loved being a mother. Loved them both as soon as I laid eyes on them, and more and more in the weeks that followed. Until then, I hadn’t understood how profound love could be.

Not that having two of them wasn’t challenging. Demanding of everything I had to give and then some. While Orion was away at work all day, I was home changing diapers, feeding them, grabbing ten-minute naps whenever—miraculously, rarely—their sleeping schedules coincided. And true to his word, Orion was a devoted father. When he’d get home from the college and see them, his face would light up. He’d bathe them, walk with one of them in each of his arms, rock them until they’d both gone down for the night. Part of the night, anyway. Andrew was a colicky baby, and it would drive me crazy when he’d cry and wake up his sister. And then Ariane would start crying, too. Our marriage suffered for that first year or so. Orion would come home tired from dealing with his patients and give whatever energy he had left to the twins. I resented that he didn’t have much left for me. But I didn’t have much left for him, either. Double the work, double the mess. Carting both of them to the pediatrician’s when one of them was sick. And then going back there the following week when Andrew came down with what Ariane was just getting over. Sitting in that waiting room with those other mothers—the ones with singletons who were always making lunch dates. Playdates. They’d ooh and ah over my two but never invite me to join them. Not that I even wanted to, but why hadn’t they ever asked? They always acted so confident, those moms. It was as if everyone but me had read some book about how to be a good mother …

But I had read the books. Consulted Dr. Spock so often that the binding cracked in half and the pages started falling out. But I had no mother of my own to rely on the way those other women did. Those grandmothers who could spell their daughters. Babysit for them, advise them …

Still, I could have had that kind of help. How many times had Orion’s mother volunteered to drive up from Pennsylvania and help out? Maria was retired by then, available. She kept offering. It’s just that she acted so goddamned superior! Made me feel even more insecure. When I got that breast infection? Said I was thinking of bottle-feeding the babies because I was in such pain? She just looked at me—stared at me like how could I be so selfish? And then, without even asking me, she had that woman from the La Leche League call and talk me out of it.

Because she wanted what was best for her grandchildren …

And she always knew what was best. Right? Not me, their own mother. She never said as much, but I got the message. Her son had made a mistake, had married beneath himself. He should have stayed with what’s-her-name.

You remember her name, Annie. How could you forget when Maria was always bringing her up to him? “Thea’s gotten a fellowship, Thea’s gotten her book taken.” Thea this, Thea that, like I wasn’t even standing there. So no, I didn’t want her help or her advice. Who was she to pity me?

But you showed her, didn’t you? Didn’t even go to her funeral. Hey, I couldn’t go. Both of the twins had come down with the chicken pox. What was I supposed to do—leave them with a sitter?

Except I did leave them with one. I had just started making my art. I wanted to be down there working on it, not upstairs with two sick kids. So I hired that Mrs. Dunkel to watch them … He was down there in Pennsylvania for almost three weeks! Sitting with Maria at the hospital. Calling me with the daily reports. “I don’t think it’s going to be long now. She seems to be going downhill fast.” And then, in the next phone call, it would be, “She was better today. Awake, alert. I fed her some pudding, and she managed to eat about half of it.” The twins were running fevers, crying, clinging to me. But I was supposed to celebrate because she had had a few bites of pudding? And okay, Maria was his mother. But I was his wife, the mother of his kids. We needed him, too. I was going out of my mind.

But that was no excuse. I shouldn’t have hit him even if he wouldn’t stop scratching his chicken pox. I’d tell Ariane to stop, and she would. But not Andrew. So I slapped him on his tush, harder than I meant to. At first he just looked at me, shocked, and then he cried and cried. I was so scared. What kind of a mother hit her child that hard? It left a mark. But by the next day, it faded. If I had let him keep scratching, he would have had scars for the rest of his life.

And what was Orion supposed to do? He couldn’t abandon his mother, no matter how long she lingered. But when she finally did die, there were the arrangements to make, the funeral, cleaning out her condo for resale … And that babysitter hadn’t worked out anyway. How could I concentrate on my work when they were up there crying, calling for me, banging on the basement door?

But I did not boycott Maria’s funeral. I stayed home with our sick kids. And then he tells me that Thea flew in to pay her respects. That the two of them went out to dinner after the services. And I started wondering about how else she might have comforted him …

Okay, Annie, you were insecure, even if, deep down, you knew he wouldn’t cheat on you. But then when he finally gets everything squared away down there in Harrisburg, he pulls into the driveway and walks in the door like the returning hero. “Daddy! Daddy’s home! Give us a pony ride, Daddy. Read us a bedtime story.” He shows up again, they’re over the worst of their chicken pox, and suddenly I’m irrelevant. The fun parent was back. The good cop. Who cares about Mommy now that Daddy’s back? And I resented that. Held on to that resentment until we landed in couples counseling.

Because he didn’t value my work. That’s why we were having trouble. Because everything was about his work, and mine didn’t count. I was just supposed to be home with the kids all day, at their beck and call, and then grab an hour or two after they were finally down for the night, when I was too exhausted to tap into my creativity. Half the time I’d be down there, trying to work on something, and I’d fall asleep. He’d have to come down, wake me up, and lead me upstairs to bed.

But boy, I balked at that marriage counseling idea. I thought the deck would be stacked. Me versus two psychologists. I was afraid she was going to tell me to give up my art. But instead Suzanne validated what I was doing. Helped Orion to see that my work mattered, too. And she helped me to realize the extent of his grieving for his mother. “Now that my mother has passed, it’s like we’re both orphans,” he said, trying hard to hold back his tears. “I mean, I was the result of my mother’s affair with a married man. A Chinese man who wouldn’t leave his Chinese wife for his Italian girlfriend, and then … took a powder. Just goddamned disappeared.” He had never said much about his father’s absence from his life, and until then I’d assumed he just accepted it. “The only thing I ever got from him was his last name,” he said. “And it’s different. I know it is. I had my mother a hell of a lot longer than you had yours, but …” He broke down in sobs then, and I ached as I witnessed the pain he was in. I reached over and put my hand on his shoulder. Pulled tissues from the box on the table and handed them to him. Watched him wipe his eyes, blow his nose. For the next several seconds, none of us spoke. Suzanne kept looking at me. Waiting for me to say something. And in the middle of that uncomfortable silence, I almost risked telling him my truths. My secrets were on the tip of my tongue. But then Suzanne glanced at her clock and said we had to wind up. That we’d gone a little bit over and her two o’clock would be waiting.

I don’t know. Maybe if we had kept going to those sessions, I would have told him. But we didn’t. Things were better between Orion and me—more like they’d been in the beginning. The closeness, the way he could get me to laugh. Like that time he took me to Boston—Haymarket Square—and taught me how to slurp oysters from the half-shell. Took me that first time to the Gardner Museum … And being a mom had started getting a little easier by then. The twins were growing out of the “terrible twos.” They had begun to amuse each other, catching bugs out in the backyard or going down to the stream out back to capture tadpoles and crayfish. That bond they’d developed gave me a reprieve. I could sit near them. Keep an eye on them while I was sketching out new ideas for pieces I wanted to make. And thanks to those counseling sessions, Orion had become more supportive of what I was doing. What I was trying to do. He began spelling me on the weekends so that I could do my work, go on my hunts for new materials. When I won that “best in show” prize? It was Orion who had urged me to enter the competition.

And then, in the middle of this better time, I got a little careless about birth control and along came Marissa. Our unplanned child.

He had kept promising he was going to get a vasectomy but never followed through with it. I was furious when I realized I was pregnant again, but only at first. I calmed down, just like I had with the twins. Accepted it. But my work suffered. I had to make all kinds of sacrifices because I put them first. Because I was a damned good mother …

Most of the time. But then there were those times when I wasn’t. When Andrew would make me so mad that … Because he was always goading me. Challenging me. Wasn’t that why he took the brunt of it? Or was it because, of the three kids, he has the most O’Day in him? The reddish hair, the Irish eyes. He resembles my father around the eyes. And he has my father’s walk.

And who else does Andrew resemble? Go ahead. Say it.

“Miz Anna?”

“Hmm?” I look up, startled. Our housekeeper is standing there. “Yes? What is it, Minnie?”

“I axed you if you got anything else needs washing?”

“Washing? Uh, no. Just the stuff that’s in the basket. Thanks.”

“Did I scare you just now, Miz Anna?”

“What? Oh, no. I was just thinking about something else.”

Minnie doesn’t say so, of course, but I get the feeling she doesn’t really approve of two wealthy women marrying each other. Or maybe she just doesn’t get why we’d want to … Our housekeeper: I feel guilty even thinking it, let alone saying it out loud, which I did to Hector yesterday when he showed me the umbrella he’d found leaning against the wall downstairs in the lobby. “This isn’t yours, is it, Miss Oh?” he asked me.

“No, but I’ll take it. It’s our housekeeper’s. Thanks, Hector.” I reached into my purse, took a twenty from my wallet, and held it out to him.

“No, no, that’s okay. This thing don’t look like it cost twenty bucks to begin with. You don’t have to tip me all the time.” But I waved away his resistance and made him take it. I had just withdrawn two hundred dollars from the ATM at that Korean grocery store around the corner, so there were nine other twenties in my wallet. It wasn’t as if I was going to miss the tenth. Twenty dollars: what’s that these days? A taxi ride up to the Guggenheim plus tip? A couple of those fancy coffee drinks at Starbucks and a slice of their pricey pound cake? I’d rather let Hector have it.

Hector’s affable and he’s a talker. He works construction during the week, at the site where they’re building the 9/11 memorial. Works at our building on weekends. I like it when he tells me about his life. He has custody of his three kids for reasons he’s not gone into with me. One boy and two girls—the same as Orion and me, although his kids are still young. They’re beautiful children; he’s shown me their parochial school pictures. Now that school’s started again, he pays a neighborhood abuela to watch the kids from the time they get home until the time he does. His sister takes them on the weekends when he’s here. When I asked him once if it bothered him to work every day in that hole where the towers used to be, he shrugged and said that thing everyone says now: “It is what it is.” Ariane used to have that feminist poster in her bedroom: Rosie the Riveter, flexing her bicep, and beneath her, the motto: We can do it! Obama’s campaign motto last year was a variation on that. “Yes, we can!” he promised, and we needed so much to believe him that we actually elected a black man. I remember staring at the headlines and the TV news the morning after the election, in happy disbelief. But the economy’s even more of a mess than it was, our kids keep dying over there in those wars we started but can’t end, and it’s turned out that Obama isn’t a superhero after all. Maybe that’s the legacy of those fallen towers, all those lost lives: our national feeling of futility. No, we can’t do it. It is what it is. And who’s most affected by the way things are now? Not the people who can still afford the prices at the pump and at Starbucks. I heard on the news the other day that 77 percent of the children in New York’s public schools qualify for free breakfast and free lunch. That by next year, the unemployment rate may reach past 10 percent.

Last weekend, Hector was on second shift. Earlier that day, he’d borrowed his sister’s car and taken his kids to Six Flags for a last summertime hurrah. But coming back, the car broke down, and he was over an hour late. I’d just come back from a movie, and the building manager was berating him right in front of me while I waited for the elevator. There’d been complaints, he said, about the entrance being left unsupervised. Hector was mistaken if he thought he was irreplaceable; there was a stack of applications sitting on his desk. “And who do you think’s going to have to stand there before the co-op board and listen to them gripe this coming Monday? You, Martinez? No, me, that’s who.” I wanted to walk over there and ask that stupid manager if he’d ever been late. If he was perfect. What was that thing Jesus said when he was defending the adulteress? Let he without sin cast the first stone. But then the elevator doors opened, and I got in and pressed five without having said a thing. When Viveca called me from Greece and I mentioned the incident between Hector and the building manager—told her I wish I’d spoken up—she said it was probably better that I hadn’t. “The co-op board doesn’t like it when tenants get mixed up in issues involving the help,” she advised …

My daughter Ariane wouldn’t have been a wimp about it; she’d have jumped right in and stuck up for Hector. She’s been a defender of the underdog ever since she was a kid. There was that time in high school when she had the party on prom night for all the girls who, like her, hadn’t been asked. I can still hear them all, down in our rec room, laughing and playing music, yakking away. And then there was the time when she defended that mentally retarded boy who was being taunted by the bullies. They were getting their kicks by circling him and pitching pennies at him, and Ariane had elbowed her way past them, taken the boy by the hand, and led him out of the circle. The bullies had targeted her for a few days after that, but when they saw that they couldn’t get to her, they knocked it off. It had stopped being fun …

The help: it angered me, that superior tone, but I kept my mouth shut. That co-op board is like some kind of supreme body around here that everyone’s supposed to kowtow to. Before I moved into the building, Viveca had to have them approve my occupancy of her guest room, which, in my opinion, was bullshit. Whose apartment is it? Hers or theirs? The co-op board: they’re like those athletic boys in junior high that the principal picked to be hallway monitors. They’d put on their sashes and boss around the rest of us mere mortals. Move to the right! No talking during passing time! I said no talking! What are you, deaf? How’d you like to get reported? Goddamned Gestapo hall monitors. Well, it was previews of coming attractions. It’s not as if, after you leave junior high, you’re ever going to be free of bullies. They follow you through life. And okay, maybe I didn’t say anything when that stupid building manager was chewing out Hector. But my art says it. What did it say in that Village Voice review of my last show? That my pieces are political. Howls of protest against the misuse of power. Something like that …

Coffee. I need coffee. Maybe a couple of cups of caffeine will motivate me to get to the studio today. I’m not sure why I’ve been avoiding going there, or why I lied to Viveca and said I was going. Is it wedding nerves? Has my creativity begun to abandon me? I take the beans out of the freezer (fair-trade, Guatemalan, thirteen dollars a pound at Zabar’s). Grind them, hit the “brew” button. Everything’s high end here. This new coffeemaker Viveca had sent over from Saks brews espresso and cappuccino, froths up milk for latté. I should check the manual; for all I know, it’ll dust the furniture and wipe your rear end for you as well. When it arrived, I saw the price on the receipt: seven hundred dollars. Jesus! The last I checked, you could get a Mr. Coffee on sale for $19.99 … Comfort the disturbed, disturb the comfortable. Maybe that’s it. Maybe I’m avoiding the studio because my life’s become too goddamned comfortable.

To stop thinking, I put on the TV, the morning news, and there’s Diane Sawyer, looking as pretty as ever. She must be in her sixties by now. Has she had work done? Have her lips always been that full, or have they been plumped with collagen? These are New York questions. Before I moved to Manhattan, I wouldn’t have given a rat’s ass one way or another. Well, she’s probably got her burdens, too. Ratings wars, celebrity stalkers. Being that famous must be so strange … Last week, when I recognized Diane’s husband buying toothpaste at that Duane Reed, I couldn’t remember any of the movies he’s directed, but what I did recall was that his family had had to escape from the Nazis when he was a little boy, and that some childhood illness had left him without body hair. Passing him in the aisle, I glanced over to see if he had eyebrows, but when he caught me looking, I had to turn away. It’s not that I’m a celebrity. Far from it, thank god. But I’m known in the art world now to some extent—here in Manhattan at least. How would I like it if some collector knew more about my shitty childhood than they did about my work?