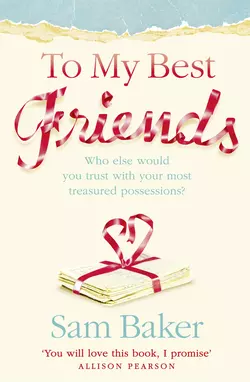

To My Best Friends

Sam Baker

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.17 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Nicci Morrison was always the first of her friends to do everything…But she wasn′t meant to be the first to die.Saying goodbye is never easy, but at least Nicci has one last chance to make a difference before she goes. She’s decided to leave letters giving her most treasured possessions to her closest friends.To her single friend Mona she bequeaths her husband David, little knowing her best friend found The One a long time ago…To childless Jo, Nicci leaves the care of her three-year-old twin daughters. Jo however is finding it hard enough to cope with the fortnightly arrival of her stepsons. To Lizzie she leaves her garden. But while Lizzie is loyally tending Nicci’s plants, the parts of her own life that are in desperate need of attention are falling by the wayside.But Nicci didn’t always know best, and she couldn’thave imagined the changes and challenges her letters set in motion for the loved ones she’s left behind.