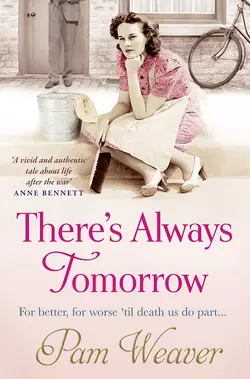

There’s Always Tomorrow

Pam Weaver

When Dottie’s husband Reg receives a mysterious letter through the post, Dottie has no idea that this letter will change her life forever.Traumatised by his experiences fighting in World War II, Reg isn’t the same man that Dottie remembers when he is demobbed and returns home to their cottage in Worthing. Once caring and considerate, Reg has become violent and cruel. Dottie just wants her marriage to work but nothing she does seems to work.The letter informs Reg that he is the father of a child born out of a dalliance during the war. The child has been orphaned and sole care of the young girl has now fallen to him. He seems delighted but Dottie struggles with the idea of bringing up another woman’s child, especially as she and Reg are further away than ever from having one of their own.However, when eight-year-old Patsy arrives a whole can of worms is opened and it becomes clear that Reg has been very economical with the truth. But can Dottie get to the bottom of the things before Reg goes too far?A compelling family drama that will appeal to fans of Maureen Lee, Lyn Andrews, Josephine Cox and Annie Groves.

Pam Weaver

There’s Always Tomorrow

Copyright

AVON

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 2011

Copyright © Pam Weaver 2011

Pam Weaver asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9781847562678

Ebook Edition © MAY 2011 ISBN: 9780007443284

Version: 2014-12-12

Dedication

This book is dedicated to David, my husband, my lover and

my best friend, who never stopped believing in me.

Contents

Title Page (#u2465fbcb-5937-52e1-baf6-65e82d3f4953)

Copyright

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Twenty-nine

Thirty

Thirty-one

Thirty-two

Thirty-three

Thirty-four

Thirty-five

Thirty-six

Thirty-seven

Thirty-eight

Thirty-nine

Forty

Forty-one

Forty-two

Forty-three

Forty-four

Forty-five

Forty-six

Forty-seven

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

One

Dottie glanced at the clock and the letter perched beside it. It was addressed to Mr Reg Cox, the stamp on the envelope was Australian and it had been redirected several times: firstly ‘c/o The Black Swan, Lewisham, London’, but then someone had put a line through that and written ‘Myrtle Cottage, Worthing, Sussex’, and finally the GPO had written in pencil underneath, ‘Try the village’.

Australia … who did they know in Australia?

She picked it up again, turned it over in her hands. Holding it up to the light, she peered through the thin airmail paper at the letter inside. Of course, she wouldn’t dream of reading it. It was Reg’s letter – but she couldn’t help being curious.

There was a name on the back of the envelope. Brenda Nichols. Who was she? Someone from Reg’s past perhaps? He never talked about his war experiences, but perhaps he’d done some brave deed and Brenda Nichols was writing to thank him …

There was a sudden sharp rap at the front door and Dottie jumped.

Nervously stuffing the letter into her apron pocket, she opened the door. A boy with a grubby face stared up at her. ‘Billy!’

‘Mrs Fitzgerald wants you, Auntie Dottie.’

Billy Prior wiped the end of his nose with the back of his hand. His face was flushed, a pink glow peeping out from the mass of ginger freckles, and colourless beads of perspiration trickling from the damp edges of his hairline. He was very out of breath.

Dottie smiled down at him but she resisted the temptation to tousle his hair. She knew he wouldn’t like that any more. Billy was growing up fast. He’d take the eleven plus next year and maybe he’d be clever enough to go to grammar school. As he stood there twitching for an answer, she guessed why he’d come. There was obviously some hitch back at the house and he’d run all the way, keen to do an errand regardless of whether he might get a sixpence for his trouble. He was a good boy, Billy Prior. Conscientious. Just the sort of son any mother would be truly proud of.

‘She says it’s a pair of teef that you come,’ Billy ventured again.

Puzzled, Dottie repeated, ‘It’s a pair of … Oh!’ she added with an understanding grin, ‘you mean it’s imperative that I come?’

‘S’right,’ he nodded.

‘You can go back and tell Mrs Fitzgerald I’ll be there directly.’

‘If you please, Auntie Dottie …’ Billy began again, as she turned to go back indoors. ‘Mrs F said it was urgent.’

Dottie’s fingers went to her lips as she did some quick thinking. Should she leave a note on the kitchen table and go back with Billy? Her mind raced over the preparations she’d already made for the wedding party taking place the next day. Everything was under control; she’d left nothing to chance. Whatever Mariah Fitzgerald wanted, it couldn’t be anything serious. Dottie smiled to herself. People like her always needed to feel in charge. To Mariah, any slight hitch seemed like a major disaster. Dottie looked down at Billy’s anxious face and her heart went out to him. ‘Has there been a fire?’

‘No.’

‘Did you see an ambulance at the house?’

Billy frowned. ‘No.’

‘In that case, Billy,’ she said, ‘the message is the same. Tell them I shall be there directly.’

Billy sniffed and wiped the end of his nose with his hand, palm upwards. He seemed rooted to the spot.

‘Off you go then.’

He turned with a reluctant step. ‘It’s urgent,’ he insisted.

‘I know, I understand that. It’ll be all right, Billy. I promise I will come as soon as I can.’

She watched him go back down the path, worried in case he walked too near the old disused well. Even though Reg had put a board over the top, and weighted it down with a stone, she didn’t like anyone walking too close.

Billy’s shoulders slouched, so as he reached the gate she called, ‘Just a minute, Billy.’

He turned eagerly, obviously expecting her to run all the way back with him. Instead, she went back inside and reached up onto the mantelpiece where Reg kept his Fox’s Glacier Mints in a tin. She took it down and looked inside. There were still plenty. She’d filled it up the day before, but he’d been busy last night so most likely he hadn’t had time to count them yet. Should she risk it? He could so easily fly into one of his rages if she touched his things. She could hear Billy kicking the doorstep as he waited anxiously, scared of getting into trouble. Should she? Yes … she’d take a chance. She went back to the door and held the tin out in front of the child. ‘A sweetie for your trouble.’

Billy’s face lit up. By the time he’d reached the gate again, the treat was already in his mouth.

‘And don’t throw the paper on the floor,’ Dottie called after him. She chuckled to herself as she watched him quickly change the position of his hand and slide the paper into his pocket.

The clock on the mantelpiece struck five. She’d better get a move on. Reg would be back home soon, another ten minutes or so. If she had to go back to the doctor’s house, she’d be there half the night. She’d better tidy up her sewing and shut up the chickens right now. Reg would see to the vegetables after he’d had his tea. With all the rain they’d had lately, they might not even need watering. According to the wireless, 1951 had seen the coldest Easter for fourteen years, the coldest Whitsun for nine years and, with the height of summer coming up, things didn’t look so promising for that either. Everybody grumbled and complained – everyone except Reg. He didn’t seem to be too worried.

‘All this rain is good for the celery,’ he said. ‘And it’ll help keep down the blackfly on the runner beans. Save me buying Derris dust this year.’

Dottie folded away the pink sundress she was working on and put it in her sewing box. The potatoes were beginning to boil. As she grabbed a handful of chicken feed from the tin by the back door, she turned down the gas and hurried down the garden.

Dottie had lived in their two-up-two-down cottage on the very edge of the village for eleven years. At sixteen, she’d come to live with her Aunt Bessie and now, nearly two years on from Aunt Bessie’s tragic death, she lived here as Reg’s wife. She smiled as she recalled her wedding day. How handsome he’d been in his uniform. He’d been so nervous, his hands had trembled as he put the ring on her finger. If she had been tempted to practice philosophy, Dottie would say that in life some are the haves and others the have-nots and, despite the sadness of the past, she was still one of the haves. She had come from nothing and now she had a nice little home, good health and – if she was careful – Reg was all right … Apart from the times when his horrible moods got on top of him, and he couldn’t help that, could he? What was it Aunt Bessie always used to say to her? ‘You make your bed and you must lie in it.’

She opened the gate leading to the chicken run and closed it behind her, calling as she went. The chickens clucked contentedly around her ankles, clearly recognising her position as provider.

‘Chick, chick, chick …’

She opened the door of the henhouse and threw in the seed. Most of the hens scrambled inside straightaway. She had only to coax a few stragglers to go in before she closed and locked the door. They were still noisy and agitated, but they’d soon roost on the perches and quieten down. Satisfied that all was well, Dottie turned back to the house. She saw that Reg had arrived and was putting his bicycle into the shed. Her heart beat a little faster. He had lost some weight since his illness but he still had his good looks and his hair was still as black as jet. She paused, waiting to see what kind of mood he was in.

‘Got the tea ready?’ he said cheerfully.

With a quiet sigh, Dottie relaxed. Thank God. He was in a good mood tonight.

‘Of course,’ she smiled.

‘What are you grinning about?’

She punched the top of his arm playfully. ‘Just pleased to see you, that’s all, silly.’

Something flickered in his eyes and she knew she’d gone too far.

‘Oh, silly, am I?’

Her heart sank and she chewed her bottom lip anxiously. ‘I didn’t mean it like that, Reg.’

As she brushed past him, he grabbed her left breast and pushed her roughly against the back door. His other hand was already up her skirt, his fingers pressing into her bare flesh above her stocking top. His breathing became quicker as, with one deft movement, he undid her suspender. She felt her stocking slip. As his urge became more acute, he pressed his body against her and she heard a crinkling paper sound coming from her apron pocket. Her heart almost stopped. She still had his letter! Her mind went into overdrive. He mustn’t know. Please, please don’t let him feel it. Please don’t let him ask, ‘What’s that noise … What have you got in your pocket?’ She could feel it getting all creased up. If he found out, what would she say? How on earth would she explain?

He was kissing her so hard she hardly had time to draw breath. His tongue filled her mouth and she could feel the rough stubble on his chin rasping against her face. She tried to respond to him – he got so angry if she didn’t – but she couldn’t. Her only thought was the letter.

The door latch was digging into her side and it took all her willpower not to push him away. Another thought came into her mind. He wasn’t going to make her do it here, was he? Not here by the back door, out in the open, where anyone could come around the side of the house and see them? What if Ann Pearce looked out of her bedroom window? She’d never be able to look her in the face again.

‘Come on,’ he said hoarsely, pinning her to the door with one hand and fumbling with the buttons on his trousers with the other. ‘Come on.’

‘Reg …’ she pleaded softly. ‘Let’s go inside.’

He pushed her again, banging her head painfully against the door as he lifted his knee to prise her legs apart. All at once, he stopped fumbling with his flies and slid his hands over her buttocks. Her skirt went up at the back.

‘No,’ she pleaded. ‘Not here, not under Aunt Bessie’s window.’

He froze. She looked up and he was staring at her coldly. His lip curled and he punched her arm.

‘Oh bugger you then,’ he snarled as he walked into the house.

Dottie grabbed the window ledge to steady herself. ‘I’m sorry,’ she whispered. She stayed where she was for a couple of seconds, her knees trembling and her hair dishevelled. Lifting the hem of her skirt, she pulled at her suspender to secure her stocking again. The back of her head was tender but thankfully there was no sign of blood. She glanced into her apron pocket. The letter was completely crumpled. She couldn’t give it to him now. He’d go loopy.

Taking a deep breath, Dottie tugged at the front of her dress to pull it straight and held her head high as she walked back inside. She knew what was expected. Business as usual. They never discussed it when it happened. He didn’t like talking. Five minutes later, her apron and the letter hanging on the nail on the back of the door, she placed his plate on the table.

He put down his paper. ‘Got plenty of gravy on that?’

‘Yes, Reg.’

He got up from his chair and sat at the table.

‘I’ve got to go back to the house,’ she said, aware that she was treading on eggshells.

‘Oh?’

‘She sent Billy Prior up with a message.’

‘Won’t it keep until morning?’

‘I doubt it,’ Dottie said, risking a little laugh. ‘You know what she’s like. She’ll be in a right state. Josephine’s wedding is the wedding of the year.’

‘I can’t imagine there’s anything left to do,’ said Reg, pulling up his chair to the table. ‘Not with you in charge.’

She wasn’t sure what to make of that remark. Was there a note of pride in his voice, or was it sarcasm? She decided not to ask and went to fetch her own plate.

‘Well, you’d better get over there right away then, hadn’t you?’

‘We’ll eat our dinner first,’ she said, adding her own note of defiance. ‘She’ll send the doctor with the car before long.’

‘How do you know that?’

She shrugged nonchalantly. ‘You’ll see.’

‘I dare say I’ll look for any sign of mildew in the strawberry beds,’ he said, mashing his potato into the gravy and spilling it onto the tablecloth, ‘and then maybe I’ll take myself off to the Jolly Farmer for a pint.’

‘So it’s all right for me to go then?’ she said.

He looked up sharply. ‘Got any brown sauce?’

Just as she’d predicted, Dr Fitzgerald, a small man with a shock of frizzy light brown hair, walked up the path about twenty minutes later. Pushing his thick-rimmed glasses further up his nose, he curled his top lip at the same time, something he always did when he was slightly embarrassed.

Dr Fitzgerald had always admired the simplicity of Dottie’s little cottage. Reg kept the garden looking immaculate. The neat rows of carrots, cabbages, beans and peas kept the two of them well fed and healthy. He knew from the various occasions when he’d been called out when Reg was ill that the inside of the cottage was neat and tidy too.

Some would say he was nosy but the doctor made it his business to know all about his patients. Taking umpteen cups of tea by the fireside had enabled him to discover that, born and raised a gentlewoman in the last century, Elizabeth Thornton, known to everyone as Aunt Bessie and the original owner of Myrtle Cottage, had incurred the wrath of her father by marrying beneath her station. Cut off from the rest of the family, she and her beloved Samuel had amassed a tidy fortune in the twenties and thirties by running a string of small hotels, but sadly they remained childless. The frequency of the doctor’s visits had increased slightly in 1940, when her only living relative, orphaned by the Blitz, had come to live in the village. A terrible thing to happen to a young girl, but he couldn’t be sorry: Dottie had brought a very welcome ray of sunshine back into Bessie’s life.

He found the back door open. In the small scullery, Dottie’s pots and pans gleamed and glinted. He wondered vaguely where she found the time. He was well aware that she was in great demand in the village. On Mondays and Tuesdays, she worked for Janet Cooper, owner and proprietor of the general store in the village, and on Thursdays and Fridays she was at his own house. Dottie wasn’t the usual sort of daily help, all frumpy and with wrinkled stockings – she was attractive too. Damned attractive. Her figure was trim and her breasts soft and round. If she had one fault, it was that she wore her copper-coloured hair too tightly pulled back in a rather severe-looking bun, but now and then a tendril of hair would work itself loose and fall over her small forehead. He wasn’t supposed to, but he noticed things like that. And when she laughed, her clear blue eyes shone and she lit up the whole world. He sighed. Oh to have an un complicated life like hers … to have an uncomplicated wife like her … Mariah’s agitated face swam before his eyes.

Dr Fitzgerald cleared his throat. ‘We sent the Prior boy up, but we weren’t sure if you’d got the message,’ he began apologetically.

Dottie gave no hint one way or another. Oh dear, oh dear. He dared not return without her. ‘Um,’ he went on, ‘my wife … that is … we wondered if you could spare an hour or two tonight, Dottie?’

‘I told Billy to tell you I would be there directly,’ she said in her usual unhurried manner.

‘I see …’

‘I had to take care of my husband first.’ Although her tone was mildly reproachful, the doctor envied Reg Cox – not for the first time. When was the last time Mariah put him first in anything?

‘Yes, yes, of course,’ he said hastily. ‘Um … I was just wondering …. um … if you are able to come straight away, I could give you a lift.’

‘Well, that’s most kind of you,’ she said in a surprised tone. ‘I’ll just do this and then I’ll get my coat.’ She picked up the bowl and wandered past him to throw the washing-up water onto the garden. ‘And,’ she added as she walked past him a second time, ‘I’m sure you wouldn’t mind dropping Reg off at the Jolly Farmer on your way, would you?’

If the doctor was annoyed by her presumption, he wasn’t about to make a fuss. He wasn’t stupid. He knew that in her quiet way, Dottie controlled all their lives and for the sake of his own sanity and peace of mind, it was important for him to get their in dispensable daily woman back to his wife as soon as possible.

By the time they arrived at the house, Mariah Fitzgerald was in a complete flap. She’d got Keith running in and out of the house and into the marquee (a large ex-army tent set up on the lawn), with the large dinner plates from her best service, as well as some plates she’d found on the larder floor.

‘Don’t drop them, whatever you do,’ she’d screamed at her already nervous son. Keith tripped over the guy ropes and she almost had a fainting fit.

‘You forgot the china, Dottie,’ she said accusingly as Dottie stepped out of her husband’s car. ‘It’s a good job I went into the marquee to check. The tables were bare.’

Dottie said nothing but she was bristling with anger. Dr Fitzgerald disappeared somewhere in the direction of the surgery and she heard a door closing. She hung her coat on the peg on the back of the kitchen door and looked around in dismay. She’d expected interference to some small degree but not on a scale like this. Her beautifully organised kitchen was in total chaos.

Mrs Fitzgerald had been going through everything, even the tins in the pantry. The lid of the tin containing the strawberry shortcake was on the draining board, the tin containing the brandy snaps had the lid from the love-all cake on the top and vice versa. The tin of butterfly cakes had no lid at all. Dottie couldn’t even see it. When she’d left that afternoon, the dinner plates, on hire from Bentalls in Worthing, had been in their boxes under the shelf in the pantry. They had since been pulled out and the shredded paper used as packing was now strewn all over the kitchen worktops and the floor.

With an exaggerated sigh, Dottie set about putting things to rights. The bread bins were open and some of her carefully counted cutlery was missing from the drawer. What was the point of asking someone to do something and then changing it the minute her back was turned? Mrs Fitzgerald usually trusted her implicitly. What on earth had changed, for goodness’ sake?

Keith came in and bent to pick up some more plates.

‘You can leave them,’ Dottie said tartly.

‘But Mother says …’ he began.

‘I’ll deal with your mother,’ she said, her tone a little less edgy. After all, it wasn’t the boy’s fault. He stared at her with wide eyes. She smiled and said softly, ‘You go and have your bath.’

‘I told her you wouldn’t like it,’ Keith muttered as he turned towards the stairs.

Dottie set off in the opposite direction, towards the garden and the marquee.

‘I shouldn’t have to do this, Dottie,’ Mrs Fitzgerald wailed as she saw her coming.

‘And you don’t have to, Madam.’ Dottie’s tone made her employer look up sharply. There was no insolence on her face, but she needed to let her see she wasn’t happy.

‘There’ll be so much to do in the morning,’ said Mariah Fitzgerald. ‘Why didn’t you think to put the plates out? It would save such a lot of time, you know.’

‘They need to be washed first.’

‘Washed?’

‘I have no idea who had the plates before us, Madam,’ said Dottie. ‘I didn’t think you would want to use them unwashed so I’ve arranged for Mrs Smith and Mrs Prior to come first thing in the morning.’

Mariah Fitzgerald’s jaw dropped slightly. ‘Well,’ she flustered, as she strove to recover her composure, ‘the cutlery needs sorting out.’

‘That’s right, Madam,’ Dottie agreed. ‘And I’ve arranged that Mrs Prior will bring her little niece Elsie to do that. She’ll polish everything for ten bob.’

Mariah Fitzgerald went a brilliant pink. The napkin she was holding fluttered down onto the table. She looked around helplessly. So did Dottie. She should have come sooner. Right now, she was wishing with all her heart that she hadn’t bothered to wait for Reg when Billy Prior had knocked on the door. Now she’d have to collect up all that cutlery, take all the plates back to the kitchen and tidy up at least forty napkins before she could go back home. She might even have to iron some of them again.

Their eyes met.

‘Yes, well …’ said Mariah, patting her hair at the back. ‘I have to be up very early in the morning. The hairdresser is coming at nine thirty.’

Dottie didn’t move.

‘So … so I’ll leave you to it, Dottie.’ Mariah said, mustering what little dignity she could find. ‘As usual, you seem to have everything under control.’

Dottie watched her as she crossed the lawn and sighed. It would be at least another hour before she had everything back to the way it was before.

Reg was all set to spend the evening in the corner of the Jolly Farmer with his pint of bitter. Usually there were plenty of people still willing to buy a pint for an old soldier, but tonight the bar was almost empty. He didn’t mind. It had been a long day – Marney and the station master had had him running from pillar to post.

Marney’s chest was bad again. Too much smoking, everyone said, but Reg reckoned it was something to do with the POW camp he had been in Germany somewhere. You could pick up some weird germs in those places. Marney probably lived week in week out on the verge of starvation as well, and that couldn’t have helped. Reg might not have been in a palace himself, but his ‘rest of the war’ was nowhere near as bad as Marney’s. Even if it were the ciggies that made his cough, who could blame the poor old bugger? He probably only smoked them to forget something.

As Reg stared deeply into his pint, Oggie Wilson drifted back into his mind. He’d never forgotten poor old Oggie, and when he heard what had happened to him, he’d felt as sick as a pig. Reg never spoke of his own experiences of course. Better to let sleeping dogs, and all that, but when he’d married Dot in ’42, he knew he’d fallen on his feet. A nice little place right near the sea, two women at his beck and call – what could be better? Dottie had stuck by him all through the war and it was only the thought of coming home to her that kept him sane while he had been stuck in that bloody prison. He’d finally come back in ’48. She’d given him quite a homecoming too. Some of his mates had come back from POW camp to find their missus had given up on them. Jim Pearce’s wife had presumed him dead and when he came home he found her shacked up with somebody else. A fine how-d’you-do that was, and the woman had no shame. Reg knew what he’d have done if he’d found any woman of his cheating on him. Not Jim. He’d cleared off and she was still living next door, bold as brass.

Dottie wasn’t like that. Dottie had waited and she’d been faithful. Reg took a long swing of his beer. Nah, Dottie would never do anything bad. She was perfect. Too bloody perfect, that was her trouble. Taking her on the doorstep would have added a bit of spice to life. Why did she have to go and mention the old trout? Bloody Bessie with her silly hats and passion for cowboy films, she ruined everything. Even the thought of her made his stomach turn.

He’d had the shock of his life when Aunt Bessie had died and he’d never felt the same since. It had done for his marriage as well. He’d tried to get it together but he just couldn’t do it any more. Before the war, he could keep it up for hours, especially if he knew Bessie was listening on the other side of the paper-thin walls. He was a bit rough at times but he’d had enough women to know most of them liked it that way. But ever since … well, since then he just couldn’t do it any more. Not with her, anyway.

Dottie had never reproached him for it. She was too anxious to please. Sometimes he wished she would. He took another long drink. Trouble was, she never fought back. Whatever he dished out, she just took it. Well, that was no fun, was it? She was beginning to bloody annoy him all the time now.

‘Hey up, Reg. You coming outside?’

He put his empty glass down and looked up. Tom Prior from the Post Office was leaning in, holding the door open. ‘We’re bowling for a pig,’ he cajoled.

‘A pig?’

‘Nice little thing,’ Tom went on. ‘Fatten him up and he’ll be a lovely bit of bacon when Christmas comes.’

Taking in Tom’s weedy frame, the thought crossed Reg’s mind that he could do with a bit of fattening up himself. Naturally skinny, he and that fat cow Mary looked like Jack Sprat and his wife.

Reg shook his head. ‘Nah, I’ll settle for a bit of peace and quiet.’

‘Peace and quiet!’ Tom chortled. ‘You’ll get plenty of that when you’re in your pine box and staring at the lid. Come on, man. Let’s be havin’ you. I’ll stand you another pint and it’s only two bob a go. All in aid of the kiddies’ home.’

Reg rose from his chair. ‘I don’t know why I listen to you, Tom Prior,’ he grumbled good-naturedly. ‘I never bloody win anything.’

Dottie had worked hard and now she was very tired. The marquee was almost back to the way it had been and the kitchen was nearly straight when Miss Josephine, the bride to be, came downstairs in her dressing gown and wearing slippers.

She wasn’t exactly a pretty girl. Her nose was slightly too long and her mouth definitely too wide; but Dottie knew that just like any other bride she would look radiant in the morning. Right now the whole of her hair was kiss-curled, each one pinned together by two hair grips crossed over one another. Her face was white, and the Pond’s Cream, thick enough to be scraped off with a palate knife, hid every blemish on her skin. She was wearing little lace gloves so she’d obviously creamed her hands and, to judge by the puffiness of her eyes, she’d been crying for some time.

‘Are you making some cocoa, Dottie?’

‘I can easily make some for you, Miss.’

Dottie went to fetch the milk and a saucepan. Josephine sat at the kitchen table. ‘Oh, Dottie,’ she sighed.

Dottie was tempted to ask, ‘Excited?’ but the tone of the girl’s voice led her to believe her sigh meant something altogether different. ‘What is it?’

‘Can you keep an absolute secret?’

‘You know I can,’ said Dottie, striking a match. The gas popped into life and she turned it down.

‘I’m not sure.’

‘Not sure of what, Miss?’

‘That I can go through with all this.’ Josephine produced a lace-edged handkerchief from her dressing-gown pocket and wiped the end of her nose. ‘I tried to tell Mummy, but she just got cross and shouted at me. Then she said she didn’t want to talk about it because she’d forgotten to do something really important in the kitchen.’

Ah, thought Dottie, careful not to let Miss Josephine see her lips forming the faintest hint of a smile. Mrs Fitzgerald had sent for her, not to sort out a few stray plates, but to stop her daughter from calling off the wedding.

Dottie reached for the Fry’s Cocoa, mixed a little of the powder with some cold milk in the cup, then added the boiled milk. She kept her voice level, unflappable, as she asked, ‘What’s the problem?’

‘I don’t know,’ Josephine wailed. ‘And before you tell me it’s just nerves, let me tell you it’s not.’

‘Do you love Mr Malcolm?’ Dottie put the cup and saucer in front of her, still stirring the cocoa.

‘Yes, of course I do!’ She dabbed her eyes again. ‘How can you ask such a thing? It’s just that I don’t … I can’t …’ Her chin wobbled. ‘Oh, Dottie, supposing …’

‘Every young woman is nervous on her wedding night,’ said Dottie sitting down at the table with her. ‘But if you love him …’

‘I do, I do!’

‘And he loves you?’

‘He says he does. He’s so … Oh, Dottie, you’re a married woman …’

Dottie thought back to her own wedding night. All those old wives’ tales her friends teased her with. They only did it because they knew her innocence. What they couldn’t know was that their teasing fed her fear of the unknown, the fear of failure, the dread of being hurt. But back then, all her worries had been blown away by her feelings for Reg. Poor lamb, he’d never known real love. He’d never even known a mother’s love because he’d been brought up in a children’s home. When she saw him waiting at the front of the church on her wedding day, her heart had been full to bursting. Now at last, she would be able to show someone how much she cared and as they’d walked into her honeymoon guesthouse, her one and only thought had been that she would be giving him something he’d never had before. Something very precious …

‘Haven’t you ever?’ she began, but one glance at Josephine’s wide-eyed expression told her what the answer was. Dottie reached out her hand in a gesture of affection. ‘Mr Malcolm knows you’ve never been with anyone else,’ she said gently.

‘But I won’t know what to do,’ Josephine wailed. ‘Supposing I fail him? Supposing being married doesn’t work?’

‘Of course it will work,’ said Dottie. ‘Even if it’s difficult to begin with, you’ll make it work.’ That’s what we women do, she thought to herself. Men pretend everything is fine or go down to the pub, but we get on with it and make it work.

Josephine leaned forward. ‘Dottie …. do you mind? I mean … would you tell me? What happens when you and Reg …? Oh, I shouldn’t ask that, should I? It’s not nice. But what happens …? I mean, exactly …?’

Dottie glanced up at the clock. What should she say? If she told Josephine how things really were between her and Reg, there would be no wedding. Mr Malcolm seemed a nice enough man. A bit of a chinless wonder as Aunt Bessie would say, but he clearly loved her. Reg had been good and kind in the beginning. Her wedding night had been a little … rushed … but she knew he loved her really. It was only the war that changed him. All that time he was away, she’d dreamed of what it would be like to have him back home again. It wasn’t his fault things weren’t the same. Aunt Bessie was right. She always said, ‘War does terrible things to people.’

‘Dottie?’

Josephine’s voice brought her back to the present. She leaned towards her employer’s daughter as if she were about to whisper a secret. She wouldn’t spoil it for her. She wouldn’t tell her how it was, she’d tell her how she’d always dreamed it would be.

Two

When at last Dottie walked outside into the cool night air, Dr Fitzgerald came out through the French windows.

‘I’ll take you home, Dottie.’

She was startled. ‘There’s no need, sir. I’m quite happy to walk.’

‘Nonsense!’ he cried. ‘You’ve got a big day tomorrow. You’ll need all your strength. Hop in.’

He was holding the passenger door of his Ford Prefect open as if she were a lady.

‘Everything set for the reception?’ he said as he sat down in the driver’s seat.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘You’re an absolute marvel, Dottie.’

‘Not at all, sir,’ she said. ‘I’m only doing what anyone else would do.’ But in the secret darkness of the car, she allowed herself a small smile. Yes, let him appreciate her. It was only right.

Reg still wasn’t back from the Jolly Farmer when she got indoors. It was unusual for him to be out this late on a weeknight. Still, he had a half-day off tomorrow. He’d be back home at lunchtime.

She put the kettle on a low gas while she pinned up her hair and put on a hairnet. By the time she’d finished, the overfilled kettle began to spit water so that it coughed rather than whistled. She filled the teapot and sat at the kitchen table. It was lovely and quiet. The only sound in the room was the tick-tock of the clock. Then, all at once, there was a knock at the kitchen window and she jumped a mile high. ‘Who’s there?’

‘It’s me, Reg.’

Dottie pulled back the curtain. ‘Oh, Reg!’ she gasped clutching her chest. ‘You scared the life out of me. What are you doing knocking on the window?’

‘Come here, Dot. I’ve got something to show you.’

Remembering how he’d grabbed her when he came home earlier that evening, her heart beat a little faster. She shivered apprehensively. ‘I’m very tired, Reg.’

‘It won’t take a minute.’

What was he up to now? And what was that under his arm? Slipping her feet back into her shoes, she made a grab for her coat hanging on the nail on the back of the door. As she lifted it, her apron hanging underneath swung sideways and the pocket gaped open to reveal Reg’s creased-up letter. Oh flip! The sight of it made her stomach go over. She’d forgotten all about it.

‘Hurry up,’ he shouted from the other side of the door.

Dottie grabbed the apron, rolled it up and stuffed it into the drawer. ‘Just let me get my coat on.’

As she stepped outside into the cool night air, whatever he was holding under his arm moved. Dottie cried out with surprise.

‘Take a look at this!’ he said, flinging the jacket back.

It was a small piglet. The animal wriggled and squealed.

‘Where on earth did you get that?’ she gasped.

‘I won it,’ he laughed. ‘Tom Prior persuaded me to have a go at skittles and I was the only one who got them all down with one throw. I got the first prize. The pig.’

‘But you never win anything,’ Dottie said.

‘That’s what I bloody said,’ Reg agreed. ‘But this time I did.’

‘But what are we going to do with it?’

Reg shrugged his shoulders. The pig protested loudly so he covered it with his coat again.

‘Well, we’ll have to put it in the chicken run for now,’ she said. ‘They’re all shut up for the night. Has it been fed?’

He shrugged again. ‘Shouldn’t think so.’

‘There’s some potato left over from last night, and some peelings in the bucket waiting to go on the compost heap. I’ll do a bit of gravy and you can give it that.’

‘If we fattened him up,’ he said, leading the way down the garden to the chicken run, ‘he’d be a nice bit of bacon by Christmas.’

They put the pig in the chicken run and, while Reg pulled an old piece of corrugated iron over the tree stump and the edge of the fence to give it a bit of shelter if it rained, Dottie ran back indoors to get some food.

Later that night, as they both climbed into bed, Reg said, ‘I reckon I’ll get ten bob, a quid, for that pig if I’m lucky.’

‘We’d need a proper pigsty,’ she challenged, as she switched off the light by the door and fumbled her way into bed. ‘It’ll upset my chickens.’

‘Blow your chickens,’ he snapped. ‘You think more of them than your own bloody husband!’

With that, Reg turned over, snatching most of the bedclothes. A few minutes later, he was snoring. Dottie lay on her back staring at the ceiling. First thing in the morning, she’d iron that letter smooth and put it back beside the clock.

Josephine Fitzgerald’s wedding day dawned bright and sunny. Dottie was up with the lark, but Reg had already gone to work. He had to be at Central Station in time for the 5.15 mail train in order to help load up the mail bags from the sorting office in Worthing.

As soon as she was dressed, she got out the iron. She had to stand on the kitchen chair in order to take out the light bulb and plug it in, then she switched it on and waited for it to warm up.

Somebody knocked lightly on the kitchen window. She looked up in time to see the tramp scurrying behind the hedge. He’d been here many times before but Dottie hadn’t seen him for ages. In fact, it had crossed her mind that perhaps he’d died during the cold winter months, or maybe moved on to another area.

Whenever he turned up, Aunt Bessie always gave him something, a cup of tea or a piece of bread and jam. They all knew Reg didn’t like him around so he planned his visits carefully.

Dottie popped out to the scullery to put on the kettle to make him some tea, and to get the rolled-up apron out of the drawer. Taking out the letter, she held it to her nose. It smelled of nothing in particular, but now that it was close up, she could see it had more than one piece of paper inside the thin envelope. There was a white sheet of paper but she could also see the edge of a smaller yellow sheet. Dottie turned it around in her hands. Who was this Brenda Nichols? Why was she writing to Reg?

Dottie and Reg first got together in 1942, on her sixteenth birthday. They’d met at a dance in the village hall and they had married after a whirlwind courtship. Aunt Bessie had paid for them to honeymoon in Eastbourne, no expense spared.

Once the wedding was over, Dottie had come back to the cottage to carry on living with Aunt Bessie, while Reg, who was in the army, had been sent to Burma. Perhaps Brenda was someone he’d met out there? All Dottie knew was that his unit was part of the Chindits. They were well respected and very brave but she had to rely on the newsreels at the pictures to give her some idea of what it must have been like for Reg because he never talked much about his experiences.

When he’d returned home three years later than most of the boys from Europe, little more than a bag of bones, Dottie had been glad to nurse him back to health. She wished that he and Aunt Bessie had got on a bit better but, try as she might, there was always a frosty atmosphere when they were together in the same room. Reg had eventually recovered physically but his war experiences left him with black moods and Dottie had to be very careful not to upset him. Was it possible that Brenda was one of the nurses who had looked after him? If she were, she would have to write and thank her.

With great care, Dottie ironed the letter flat and put it back beside the clock.

The kettle began to whistle. The tramp’s tin can with the string handle was outside on the step but, instead of being empty, there was a note inside: I did it! Thanks.

How strange. Whatever did that mean? She looked around but he was nowhere to be seen. With a shrug of her shoulders, Dottie scalded the old tin and filled it with tea the way Bessie always had. Then she cut a doorstep slice of bread and smeared it lavishly with marrow and ginger jam. She put it on the windowsill as she went down the garden with some outer cabbage leaves for the pig and some chicken food.

Motionless, the pig watched her as she let out the chickens. At first they were a little alarmed when they discovered they had a new living companion, but after a few squawks, plenty of grunting and some running about, things settled down into an uneasy truce.

When she got back to the house, the tramp’s tea and the bread were still there. Where was he? Perhaps he was afraid Reg was still around. Then she saw Vincent Dobbs, the postman, walking up the path. Obviously the tramp was waiting until the coast was clear.

‘Morning, Dottie,’ said Vince. ‘You look as if you’ve lost something.’

‘I was just wondering where the tramp was. I made him some tea.’

Vince shook his head. ‘Haven’t seen any tramps,’ he smiled, ‘but I did see some chap coming out of your gate.’

‘Who was that?’ asked Dottie, puzzled.

‘Never saw him before,’ said Vince. ‘Smart, though. In a suit.’ He handed her a letter.

‘Oh, it’s for me!’ she cried, eagerly tearing open the letter.

The letter was from her dearest friend, Sylvie. The tramp and Vince forgotten, Dottie walked indoors, reading it as she went. Sylvie was asking to come and stay for a few days when Michael Gilbert from the farm got married. Dottie had already written to tell Sylvie that Mary and Peaches and the other ex-Land Girls would be coming. Michael and Freda’s wedding, scheduled for three weeks time, might not be half so grand as the stuffy affair Mariah Fitzgerald was laying on for her daughter today, but it would be much more fun. Sylvie said how much she was looking forward to meeting up with everybody at the wedding. Dottie smiled. She was looking forward to it too. It would just be like old times.

I can’t believe that the war’s been over for five and half years, Sylvie wrote. This will be a golden opportunity to get together again. I never stop thinking about you all and the fun we had on the farm and all that blinking hard work!

Dottie laughed out loud when she read that. While everyone else had been slogging their guts out in the fields, Sylvie spent most of her time sloping off for a kip in the barn.

Write and tell me all about Freda, Sylvie wrote. What’s she like? How old is she? How did they meet? Oh, Dottie, I can’t imagine our little Michael all grown up.’

Dottie felt exactly the same way. Although there was only two years’ difference in their ages, Michael still seemed a lot younger. Freda, his bride to be, was only eighteen. Dottie didn’t know where they’d met but they had made their wedding plans very quickly; Dottie suspected that Freda might already be pregnant.

Dottie sighed. Sylvie led such a glamorous life with all those parties and important people she met, but she’d have to pick her moment to ask Reg if she could stay and that wouldn’t be easy. She knew only too well how Reg felt about her. ‘Snobby, stuck-up bitch,’ he’d say.

Dottie glanced up at the clock. 8.30. Time to go. She shoved Sylvie’s letter into her apron pocket to read again later then, humming softly to herself, she put a couple of slices of cold beef on a plate with some bread and pickles and put it in the meat safe for Reg’s dinner.

Just to be on the safe side, she propped Reg’s letter in front of the teapot on the table alongside her own hastily scribbled note – Dinner in meat safe – so that he couldn’t miss it. Then she packed her black dress and white apron into her shopping bag and set off for the big house.

Three

Mary Prior’s niece sighed. ‘Nobody’s coming yet.’

‘Good,’ said Dottie happily. ‘It must be time to put the kettle on, Elsie.’

Peaches and Mary sat down at the table.

The wedding reception was being held in the marquee on Dr Fitzgerald’s lawn. Caterers from some posh hotel in Brighton had handled all the food, but the women in the kitchen had been kept busy with unpacking and washing up the hired plates and glasses. Dottie had asked her next-door neighbour, Ann Pearce, to help out but she couldn’t find anyone to look after the kids.

Dottie looked around contentedly. She loved being with her friends and nothing pleased her more than helping to make a day special for someone.

The wedding itself was at 2pm, and once the bride had set off for the church some of them took the opportunity to pop back home. Peaches had wanted to check that her little boy, Gary, was all right with his gran. Mary wanted to get her husband, Tom, some dinner and she took Elsie with her. Dottie stayed at the house: after last night’s fiasco, she wasn’t going to leave anything to chance.

As soon as the wedding party returned from the church, the waiters began handing round the drinks and some little fiddly bits they called hors d’oeuvres. Until everyone went into the marquee for the meal, Peaches and Mary were kept busy with a steady stream of washing up.

The marquee had been set out with twelve tables, each with eight place settings. Each table was named after a precious stone – diamond, ruby, sapphire, amethyst, amber, opal, and so on – and in order to avoid family embarrassments, there was a strict seating plan. Guests were to eat their meal to the gentle sound of a string quartet.

The top table, at which the family wedding party sat, was tastefully decorated with huge vases of fresh flowers at the front, and the toastmaster was on hand to make sure that everything was done decently and in the correct order. Mariah Fitzgerald knew her daughter’s wedding would be the talk of the golf club and county set for months to come, so Dr Fitzgerald and the best man would not be allowed to move until the toastmaster had given them their cue.

The catering company had a separate tent on the other side of the shrubbery where a small team of cooks was already busy producing the meal with all the efficiency of an army field kitchen. All the washing up was to be done in the house kitchen and the team of waiters and waitresses would bring in the dirty crockery. They would send it back to Bentalls once it had been washed and repacked in the various boxes.

Dottie gave her little team a piece from one of her cakes and they sat down for a well earned cup of tea. They had been friends since the war years when they had worked together on the farm. Their friendship had deepened when Mary was widowed. It was ironic that Able had gone all through the war, only to be killed on his motorbike near Lancing. Billy was only just over five at the time and Maureen three and Susan eighteen months. Dottie and Peaches pulled together to help Mary through.

‘Well, at least the rain held off,’ Dottie said.

‘They say it’ll clear up in time for the Carnival,’ said Mary.

‘I could do with this,’ said Peaches, sipping her tea. ‘I still don’t feel much like eating in the morning.’

‘Not long now before the baby comes,’ said Mary.

‘Seven weeks,’ said Peaches leaning back and stroking her rounded tummy. ‘I can’t wait to get into pretty dresses again.’

‘I bet it won’t take you long either, you lucky devil,’ Mary said good-naturedly. ‘I looked eight months gone before I even got pregnant. Five kids later and just look at me.’ She wobbled her tummy. ‘Mary five bellies.’ They all giggled.

‘And your Tom loves you just the way you are,’ said Dottie, squeezing her shoulder as she leaned over the table with the sponge cake.

‘Our Freda is getting fat,’ said Elsie. Her eyes shone like little black buttons and Dottie guessed this was the first time she’d been included in ‘grown-up’ conversation.

‘I wouldn’t say that when Freda’s around,’ Dottie cautioned with a gentle smile. ‘She’d be most upset.’

‘I can’t wait for the wedding,’ said Elsie.

‘Michael has certainly kept us waiting a long time,’ Mary agreed.

‘But I wouldn’t call him slow,’ Peaches said, half under her breath. The baby kicked and she looked down at her stomach. ‘Ow, sweet pea, careful what you’re doing with those boots of yours, will you?’

Elsie’s eyes grew wide. ‘I didn’t know babies had boo …’

‘It’s hard to imagine Michael old enough to get married,’ Dottie said quickly.

‘Come on, hen,’ Mary laughed. ‘He’s only two years younger than you!’

She was right, but somehow, in Dottie’s mind, Michael had always remained that gangly fourteen year old in short trousers who had followed them around on the farm. It was hard to believe he was almost twenty-five.

‘I can’t wait to be a bridesmaid,’ said Elsie.

‘It’s very exciting, isn’t it?’ Dottie smiled. ‘I’m sure you’ll look very pretty.’

‘Are you doing the dresses, Dottie?’ Mary asked.

Dottie shook her head. ‘Not enough time.’

The older women gave her a knowing look and she blushed. She hadn’t meant to say that and she hoped no one would draw attention to her remark in front of Elsie. She poured Peaches some more tea.

‘I think Freda will make Michael a lovely wife,’ said Dottie.

‘Oh!’ cried Peaches. ‘This little blighter is going to be another Stanley Matthews.’

‘Pretty lively, isn’t he?’ said Mary.

‘Can I feel?’ asked Elsie.

Peaches took her hand and laid it over her bump.

‘What’s it like, having a baby?’ Elsie wondered.

‘I tell you what,’ laughed Peaches. ‘I won’t be doing this again.’

‘Why not?’

‘That’s enough, Elsie,’ her aunt scolded.

Elsie pouted and took her hand away.

‘Who did you say was looking after your Gary, hen?’ asked Mary.

‘My mother,’ said Peaches. ‘She can’t get enough of him.’

‘Tom’s got all mine,’ grinned Mary. ‘That’ll keep him out of mischief. At least you don’t have to worry about who’s going to look after the kids, Dottie.’

Dottie bit her lip. Oh, Mary … if only you knew how much that hurt …

‘Did I tell you?’ she said, deliberately changing the subject. ‘I had a letter from Sylvie yesterday.’ She took it out of her apron pocket and handed it to Peaches. ‘She’s coming to Michael’s wedding.’

Peaches clapped her hands. ‘Sylvie! Oh how lovely. She’s so glamorous. I really didn’t think she’d come, did you? We’ll have a grand time going over old times. Remember that time we put Sylvie’s fox fur stole at the bottom of Charlie’s bed?’

Dottie roared with laughter. ‘And he thought it was a rat!’

‘Jumped out of bed so fast he knocked the blinking jerry over,’ Peaches shrieked.

‘Good job it wasn’t full,’ laughed Dottie.

‘Which one was Charlie?’ asked Mary.

‘You remember Charlie,’ said Dottie. ‘One of those boys billeted with Aunt Bessie and me. The one that went down with The Hood.’

‘Dear God, yes,’ murmured Mary.

‘And is your Reg all right with her staying at yours?’ Mary wanted to know.

‘Haven’t asked him yet,’ said Dottie. In truth she wasn’t looking forward to broaching the subject.

Mary glanced over at Peaches and then at Dottie. ‘Why doesn’t he ever bring you over to the Jolly Farmer, hen?’

Dottie felt her face colour. She never went with Reg because he said a woman’s place was in the home. Mary’s pointed remark had flustered her. She brushed some crumbs away from the table in an effort to hide how she was feeling. ‘I’ve never been one for the drink.’

‘But we have some grand sing-songs and a good natter,’ Mary insisted.

Dottie took a bite of coffee cake and wiped the corner of her mouth with her finger. They’d obviously been talking about it. ‘I usually have something to do in the evenings,’ she said. ‘You know how it is.’

‘You should come, Dottie,’ said Peaches. ‘You don’t have to be a boozer. I only ever drink lemonade.’

‘I can’t think what you get up to at home,’ Mary remarked to Dottie. ‘There’s only you and him, and that house of yours is like a shiny pin.’

‘She does some lovely sewing, don’t you, Dot,’ said Peaches. ‘You ought to sell some of it.’

‘I do sometimes,’ said Dottie.

‘Do you?’

Yes I do, thought Dottie. She was careful not to let Peaches see her secret smile. And one day she’d show them just what she could do. One day she’d surprise them all.

Mary leaned over and picked up the teapot again. ‘What are you doing next Saturday?’ she asked, pouring herself a second cup.

‘Having a rest!’ Dottie laughed. What were they up to? This sounded a bit like a kind-hearted conspiracy …

‘Tell you what,’ cried Peaches. ‘Jack is taking Gary and me to the Littlehampton Carnival in the lorry. It’s lovely there. Sandy beach for one thing. Nicer for the kids. Worthing and Brighton are all pebbles. Why don’t we all go and make a day of it? You and Reg and your Tom, Mary. There’s plenty of room. We can get all the kids in the back.’

‘That sounds wonderful!’ cried Mary. ‘My kids would love it. Are you sure?’

‘I don’t think Reg …’ Dottie began. She knew full well that Reg would prefer to spend a quiet day in the garden and then go down to the pub. She didn’t mind because it left her free to work out how to do her greatest sewing challenge so far: Mariah Fitzgerald’s curtains.

‘You leave Reg to me,’ said Peaches firmly. ‘You’re coming.’

‘Can I come too?’ Elsie wanted to know.

‘Course you can,’ said Peaches. ‘The more the merrier.’

‘I don’t think you can, Elsie,’ said Mary. ‘Your mum and dad are going to see your gran over in Small Dole next week. She told me as much when I asked if you could help out today.’

Elsie stuck her lip out and slid down her chair. ‘I hate it at Gran’s,’ she grumbled. ‘It’s boring.’

Peaches had gone back to Sylvie’s letter. “All the hard work …’?’ she quoted.

‘Eh?’ said Mary.

‘She says here, “I never stop thinking about you all and the fun we had on the farm and all that blinking hard work!” I seem to remember she spent more time on her back than she did digging.’

They all giggled.

‘My dad says Mum ought to do that,’ said Elsie innocently. She was sitting at the opposite end of the table, her face covered in strawberry jam and cake crumbs.

‘But you haven’t even got a garden,’ said Mary walking round behind her to top up the teapot.

‘Not digging, Auntie! Lying on her back.’

Peaches choked on her tea as Mary made frantic gestures over the top of Elsie’s head.

‘Dad said it would do her good to lie on her back every Sunday afternoon when we go to Sunday school,’ Elsie went on innocently. ‘But Mum says she hasn’t got the time.’

‘Lovely bit of sponge this, Dottie,’ said Mary, struggling to regain her composure. ‘Elsie’s really enjoying it, aren’t you, lovey?’

‘Auntie, why are you laughing?’

‘What are you going to do with your ten bob, Elsie?’ Dottie interrupted.

Elsie smiled. ‘When the summer comes, me mum’s taking me over to me other granny’s for a holerday,’ she said. ‘She says I can keep the money for then.’

‘That’s nice.’

‘She lives near Swanage,’ Elsie was in full swing now. ‘I can go swimming in the sea.’

‘While your mum’s lying on the beach?’ muttered Peaches, starting them all off again. Desperately trying to keep a straight face herself, Dottie nudged her in the side. Elsie looked totally confused.

The door burst open and a waitress dumped a pile of dirty plates on the draining board.

‘Time to get started,’ said Dottie standing to her feet and straightening her apron. ‘Get that cake and our cups off the table, will you, Elsie? We shall need all the space we can find now.’

The next hour was a frenzy of activity. The washing up seemed endless and they were hard pushed to find space for both the clean and dirty dishes.

At around four thirty, Elsie came running back. ‘They’re all coming out!’

The women gathered by the back door to watch.

Josephine Fitzgerald looked amazing and very happy. Her dress, made of organza and lace, was in the latest style. The V-shaped bodice was covered with lace from neck to the end of the three-quarter length sleeves while the skirt was in two layers. The white organza underskirt reached the ground while the lace overskirt came as far as the knee. The whole dress was covered in tiny pearls. Dottie had studied it very carefully. She knew it had cost an absolute fortune, but with a little ingenuity she knew she could make one for less than quarter of the price.

Malcolm Deery looked even more of a chinless wonder than ever in his wedding suit but, Dottie decided, they were well matched. Josephine would lack for nothing. After a couple or three years, there would be nannies and christenings. In years to come, she’d become just like her mother, going to endless bridge parties, and playing golf. She’d buy her clothes from smart shops in Brighton or maybe go up to London to the swanky shops on Oxford Street and, if Malcolm’s business did really well, Regent Street.

‘Ahh,’ sighed Peaches. ‘Don’t she look a picture?’

‘Must be coming in to get changed before they go off for the honeymoon,’ said Mary.

Dottie didn’t want to think about the conversation she’d had the night before. Had she betrayed that girl? She hoped not, but only time would tell.

‘Second wave of washing up will be on its way in a minute,’ she said to her companions. ‘Better get back to work, girls.’

As if on cue, two waitresses hurried out of the marquee, each with a tray of glasses, followed by a waiter with a stack of dirty plates.

Mary grabbed a small sausage from the top of the pile of dishes and shoved it into her mouth as she pushed more dirty plates under the soapy water.

‘Ma-ry!’ cried Peaches in mock horror.

‘I need to keep my strength up,’ said Mary, her cheeks bulging.

‘Dottie, would you come and help Miss Josephine?’ Mrs Fitzgerald’s sudden appearance made them all jump. Mary choked on the sausage and Peaches put down her tea towel to pat her on the back.

‘Yes, Madam,’ said Dottie, doing her best to steer her employer away from her friend before she got into trouble. Mariah Fitzgerald could be very tight-fisted. Dottie could never understand meanness. Why put food in the pig bin rather than allow a hard-working woman like Mary to have a little something extra? But she knew her employer was perfectly capable, at the end of the day, of refusing to pay Mary if she caught her eating.

Thinking about pig bins, she was reminded of the pig in her hen run. How was it getting on? She’d have to ask if she could take some leftovers for him … or was it a her? How do you tell the difference, she wondered.

As she followed Mrs Fitzgerald upstairs, Dottie decided – nothing ventured, nothing gained. ‘Excuse me, Madam. About the leftovers.’

‘Put them in the pantry under a cover,’ said Mariah without turning around.

‘And the plate scrapings?’

Mrs Fitzgerald stopped dead and Dottie almost walked into her. ‘The plate scrapings?’ She sounded horrified.

‘Only my Reg has a pig,’ Dottie ploughed on, ‘and I was wondering if I could take the scrapings home to feed it.’

Mrs Fitzgerald was staring at her.

‘He hopes to fatten it up for Christmas.’ Dottie swallowed hard. ‘He says it would make a nice bit of bacon.’

‘What an amazingly resourceful man your Reg is, Dottie,’ she said, walking on. ‘Yes, of course you can take the scrapings. And when Christmas comes, don’t forget to bring a rasher or two for the doctor, will you?’

They’d reached the bedroom where Josephine was struggling with the buttons on the back of her wedding dress.

‘I’ve told Dottie to help you, darling,’ said Mrs Fitzgerald. ‘I’ll have to get back to the guests.’

As they heard her mother run back downstairs, Dottie gave the bride a conspiratorial smile. ‘Are you all right now, Miss?’

‘Oh, Dottie,’ Josephine cried happily. ‘It’s been a wonderful, wonderful day, and I know, I just know, tonight will be just fine.’

‘I’m sure it will, Miss.’

‘Mrs,’ Josephine corrected her dreamily. ‘Mrs Malcolm Deery.’ She gathered her skirts and danced around the room, making Dottie laugh.

Between them, they got her out of the wedding dress and into her going-away outfit, an attractive pink suit with a matching jacket. The skirt was tight and the jacket nipped in at the waist. Her pale cream ruche hat with its small veil set it off nicely. She wore peep-toe shoes, pink with white spots and a fairly high heel. She carried a highly fashionable bucket-shaped bag.

Mr Malcolm, who had changed in the spare bedroom, was waiting for her at the top of the stairs. He was dressed in a brown suit and as he waited, he twirled a brand new trilby hat around in his hand. The newlyweds kissed lightly and, holding hands, they began to descend. Halfway downstairs, however, Josephine broke free and ran back.

Dottie was slightly startled as she ran to her, laid both hands on her shoulders and kissed her cheek. ‘Thank you, Dottie darling,’ she whispered urgently in her ear, ‘thank you for all you’ve done.’

‘It was nothing,’ protested Dottie mildly.

‘Oh yes it was,’ Josephine insisted. ‘And if I’m half as happy as you and your Reg have been, I shall be a lucky woman.’ With that she turned on her heel and ran back to her new husband and they both carried on downstairs.

As soon as she’d gone, Dottie went back into the bedroom. As happy as you and your Reg have been? Had they been happy? If they had, it was all a very long time ago. She could hardly remember their courtship, but they had been happy in the beginning … hadn’t they?

Even her own wedding day had been rushed. The phoney war was over by then and Reg was nervous, afraid he’d be sent abroad. Under the circumstances, Aunt Bessie had been persuaded to let them marry by special licence on August bank holiday weekend. The gossips had a field day. She knew the rumour was that she was pregnant, but she was a virgin when Reg took her to bed that night.

Remembering all that the boys had gone through at Dunkirk, when Reg wrote to say he was being posted to the Far East, she’d been pleased. ‘At least he’ll be out of all this,’ she had told Aunt Bessie.

But after he’d gone, she’d felt bad about saying that. She had little idea what happened out there, but if the newsreels were to be believed it looked far worse than what happened in Germany. He didn’t want to talk about it when he came back, at the end of ’48, and he had been a changed man. His chest was bad and he needed nursing. Reg didn’t seem to want her for ages but when he recovered and tried to make love to her, he was so rough she hated it. It was hard not to cry out with Aunt Bessie next door. And that was another thing. He and her aunt didn’t see eye to eye but funnily enough, when she died, Reg had been deeply affected. The shock of it left him with another problem: he couldn’t do it. She wished she had someone to talk to, but it wasn’t the done thing, was it? A married woman shouldn’t talk about what went on behind the bedroom door.

Dottie sighed. She was still only twenty-seven and if things went on the way they were, she was destined to be barren. There would never be any babies.

She put Josephine’s wedding dress on a hanger and, hanging it on the front of the wardrobe door, she spent a little time smoothing out the creases, until the overwhelming need for tears had passed.

Four

It was cool in the shed. Reg pulled the orange box from under the small rickety table behind the door and sat down. He kicked the door closed and the soft velvety grey light enveloped him. This was his haven from the world and, apart from the occasional passing chicken that might have crept in to lay her egg under the bench, he knew the moment he shut the door he would be left alone. Dot would never come in here uninvited. This was the place where he kept his pictures. She didn’t know about them of course, but when the mood came over him and she wasn’t there, he’d come out here and have a decko. They were getting dog-eared and yellow with age but he wouldn’t part with them for the world. Although he still burned for the love of his life, he might have forgotten what she looked like if he didn’t have the pictures.

They weren’t the only pictures he had. He’d still got the ones he’d bought off some bloke at the races. Now they really got him going. Those tarts would pose any way the punters wanted them. They got him all excited and when Dot was around, doing her washing or something, he’d watch her through the knothole on the shed wall and have a good J. Arthur Rank. It wasn’t as exciting as the real thing, but he liked it when there was an element of danger. And with the way things were at the moment, he wasn’t getting much of that either.

But looking at his pictures wasn’t the reason why he’d come out into the shed today. He positioned the box near the small window and next to the place where the pinpricks of sunlight streaming through the wood knots in the boards would give him plenty of light to read the letter. Dot had propped it on the table but he hadn’t opened it. He’d shoved it straight into his pocket while he ate his dinner. He wanted to be alone when he read it, somewhere he knew he wouldn’t be disturbed.

First he took out his tobacco tin and his Rizla paper and box. As he lifted the lid, he took a deep breath. The sweet smell of Players Gold Cut filled the musty air. Putting a cigarette paper in the roll, he shredded a few strands of tobacco along its length. Then he snapped the lid shut and a thin cigarette lay on top of the box. Reg licked the edge of the paper and rolled the cigarette against the tin. He pinched out the few loose strands of tobacco from the end and slipped them back inside for another time. The years spent ‘abroad’ had made more than one mark on his character. Reg was a careful person. He hated waste and he always knew exactly how much of anything he’d got. That’s how he knew Dot had been eating his Glacier Mints. There had been twenty-four in there when she gave him the new bag. Now there were only twenty-three.

Putting the thin cigarette to his lips, he lit up and the loose strands at the end flared as he took his first drag. He laid his lighter and the Rizla box onto the bench and reached into his back pocket for the letter.

The envelope was flimsy. Airmail paper. The stamp was Australian. He stared at the handwriting and a wave of disappointment surged through his veins. It wasn’t what he thought it was. Now that he looked carefully, the sloping hand was unfamiliar. He turned the envelope over for the first time and stared at the name on the back.

Brenda Nichols – who the devil was she? He ran his finger over the writing and sucked on his cigarette. A wisp of smoke stung his eye and he closed it. The address on the front said ‘The Black Swan, Lewisham’. He dug around in the recesses of his mind but he couldn’t place it.

Reaching over to the jam jar on the shelf under the tiny window, he took out his penknife. The smoke from his cigarette drifted towards his eye again and he leaned his head at an awkward angle and closed it as he slid the knife along the edge of the envelope and tore it open. There were two sheets of paper inside the wafer-thin, transparent blue airmail envelope. The larger was white. A letter.

Reg’s hand trembled as he read slowly and carefully.

Murnpeowie. June 1951

My dear Reg

I need your help. I never told you but in ’43 I had a child. Her name is Patricia. She’s eight now. You’ll love her. Everybody does. She’s a very good girl and she will be no trouble. I cannot look after her any more. The doc tells me it’s only a matter of time. I have left Patricia with my friend Brenda Nichols but she can’t look after her for long. Her husband is sick. Please come to fetch her. I hope that deep down, you can find it in your heart to forgive me for running out on you like that but I thought it was for the best, things being the way that they are. I’m sorry for keeping this from you, but in my will I have left everything to you and I hope you will give her a good life.

God bless you,

Sandy.

There was a codicil at the bottom of the page, written in the same hand.

This letter was dictated by Elizabeth Johns to Brenda Nichols, who nursed her until she passed away peacefully in her sleep on July 15th 1951. Signed Sister Brenda Nichols.

His first reaction was panic. A kid? He didn’t want kids. That was what put him off Dot – her incessant bleating on about kids. How long he held the letter he had no idea. It was only when he realised that his cigarette was far too close to his lip that Reg stirred. He took it out, threw the dog end to the floor and ground it into the earth.

He threw the letter contemptuously onto the workbench and reached for the tobacco tin again. There was no way he was going to take in some bloody Australian bastard. He rolled another fag and stuck it between his lips while he fumbled in his pocket for the lighter. Taking a deep drag, he picked up the letter and read it with fresh eyes.

If he refused to take the kid, someone might go digging around in his past. Elizabeth Johns was dead. She’d left everything to him. That was a bit of luck. He’d need extra money if he was going to bring up a kid. Nobody would bat an eyelid if he took it. Running his hand through his own thinning hair he grinned to himself and squeezed his crotch. Yeah, he was still safe. As far as everyone knew, he was the kid’s only living relative and she was eight. She wouldn’t have a clue. What harm would it do?

Pity it all went belly up back then. He didn’t like to think about what happened when he’d got caught, and when he’d got out he was scarcely more than skin and bone. He could hardly remember those first few days of freedom. He’d been a dumb thing, beaten, exhausted, bewildered … It had been a close call, but it was worth the risk. Thank God for bloody Burma. Before the regiment was sent there, he’d never even heard of the place.

He’d written a letter to Dot telling her he was on a secret mission and given it to Oggie Wilson. Oggie owed him a favour. He’d heard after the war that Oggie had ended up on that bloody railway. When he got out, Reg tried to trace him but he couldn’t. Then someone said that they’d been forced to leave men by the roadside because the guards refused to allow them to bury the dead. He reckoned that’s what happened to Oggie Wilson. A bit of luck as far as Reg was concerned. No one left to blab. He sighed. All the same, it didn’t seem right leaving a man like Oggie out there in the open. He should have been buried, decent like. The thought of it made him shudder. If he hadn’t been caught, maybe he’d have been sent out to that bloody jungle himself, and if he had, he’d be lying beside poor old Oggie Wilson.

Putting Elizabeth John’s letter in his lap, Reg unfolded the yellow sheet of paper. It was another letter, written with a child’s hand, complete with a couple of ink stains on the page.

Dear Father,

I hope you are well. I am well. I went to MULOORINA with Mrs Unwin in her truck. We ate ice cream. I am nearly nine. I can count up to 500. That’s all for now.

Your ever loving daughter,

Patricia.

Patricia … Reg leaned back on the orange box and closed his eyes. A letter from Patsy. He liked Patsy better. His stomach was churning, the way it always churned when he was nervous. An old ITMA joke slipped between the sheets of his memories. ‘Doctor, Doctor, it really hurts when I press here.’ ‘Then don’t press it.’ He’d have to stop thinking about the past. It only made him angry. Put it out of your mind and get on with it. That’s what the screw had told them. He’d bloody tried but he couldn’t. It was the guilt mainly. He never told anyone, but sometimes he did feel bad about what happened. He felt a draught in the back of his neck and turned his head sharply, afraid that someone was standing behind him, but he was quite alone. He re-lit his cigarette and forced himself to relax.

Lifting the envelope, he put the letter back inside. Something weighted the corner. He tipped it upside down and a small photograph fell onto the workbench. Just one look at that mop of blonde hair and it was obvious why she was called Sandy. She was standing outside a bungalow. It was a sunny day and there were some funny-looking flowers growing beside the door. She was wearing a nurse’s uniform. Her hair was loose and cut short. He couldn’t make out the detail of her face – the camera was too far away – but she was holding a bundle in her arms. Bloody hell. This must be Patsy.

He was aware of his heart thudding in his chest. His mouth had gone dry. How long he stared at the small photograph he never knew. What did the kid look like now? He squinted at the bundle. Tom Prior, weedy as he was, was the father of twins and stepfather to the three others from Mary’s first husband. He always made jokes about Reg and the lead in his pencil. If everyone thought this was his kid, he’d have no trouble from now on.

In the beginning, he’d been quite pleased to get Dot. She wasn’t a bit like the sort of woman he was used to but she was all right. He’d never gone in for all that soppy stuff, but until he’d met Dot, he’d never had a virgin either. It wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. He’d tried to get her to do what he wanted, but she wasn’t having any of it. Yet she was desperate for a kid, even wept about it sometimes. She was careful not to do it in front of him but he’d heard her in the scullery. He didn’t even want her now. Since the old aunt died, she bored him.

The more he thought about being a father the more he liked it. The word sounded good. He was somebody’s dad. He had a daughter. Patricia. A nice name, Patricia, but he still preferred Patsy.

I have left everything to you … With a bit of luck Elizabeth Johns was well off when she died. For all her wealth, bloody Aunt Bessie hadn’t left him a bean. Well, this could be the big one. The only problem was Dot. She might not take too kindly to having his kid around. He didn’t want her to rock the boat so he’d have to play this one carefully. Plan it all out. And when he’d won her round, he’d have a nice little nest egg. After that, the future would sort itself out.

He opened the drawer again and took out his favourite photograph. The woman smiled up at him, her back arched and tits thrust out. She was better than Diana bloody Dors any day. He squeezed his crotch again. Right now he needed someone like her. Just the thought of her made his pulse race. She’d give him what he wanted … and more … He ran his tongue along her naked body and then shoved the photograph back in the drawer.

Taking another drag on his cigarette, Reg pulled out a writing pad and cleared a space on the worktop. For once he didn’t have to word his letter carefully in case other people read it first. All the same, he didn’t want anyone to start asking awkward questions. Licking the end of the pencil, Reg began to write.

Five

Dottie didn’t finish at the house until late. She was worn out. All she wanted to do was to get home and put a bowl of warm water on the kitchen floor to soak her poor tired feet. She was just about to set off for home when Dr Fitzgerald came into the kitchen.

‘A marvellous day, Dottie.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Have you seen my wife?’

‘I believe she’s gone upstairs to lie down.’

‘And you’re off home?’

‘That’s right.’

‘I’ll give you a lift.’

‘There’s really no need,’ Dottie protested. She rolled the plate scrapings in newspaper for the pig and put it into the shopping bag.

‘Oh, but I insist,’ said the doctor. ‘It’s starting to rain again.’

They drove in silence, but this time Dottie didn’t feel very comfortable. The doctor seemed tense. He stared at the road ahead and his back was very straight. He’s probably driving like that because he’s had too much to drink, she thought, but it gave her little comfort. The only sound in the car was the whoosh, whoosh of the windscreen wipers.

He pulled up outside her place and as he put the handbrake on his hand brushed her leg. She gathered her shopping bag, anxious to get out of the car as quickly as possible. ‘Thank you, Doctor,’ she said curtly.

‘Allow me,’ he said reaching across her to open the passenger door. Their hands met on the door handle and he pressed himself against her. ‘Oh, Dottie,’ he said huskily. ‘Dottie.’

Dottie was both shocked and surprised. ‘Dr Fitzgerald!’ she cried as his other hand squeezed her thigh gently.

‘Just a kiss,’ he was pleading. ‘One little kiss.’

His face was right in front of hers and his mouth was open. She could smell his whisky-soaked breath. She turned her head away and dug him in the ribs with all her might. Her bag fell to the floor and everything spilled out. ‘Get off me,’ she hissed. ‘How dare you!’

The wipers were still going and through the windscreen she could see the curtain in Ann Pearce’s bedroom moving. They didn’t get many cars in their street so obviously the sound of a motor drawing up had brought her to the window. The doctor accidentally touched the car horn and the loud and sudden noise seemed to make him come to his senses.

‘Oh God …’ he began. ‘Mrs Cox, I’m sorry …’