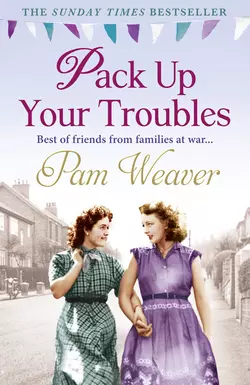

Pack Up Your Troubles

Pam Weaver

Connie and Eva are best friends but their families are the worst of enemies…During the VE Day celebrations, two women meet completely by chance. As Connie and Eva talk they discover they are from feuding families, the Maxwells and the Dixons. But when they both begin nurses’ training, they can’t deny their natural bond of friendship and become more like sisters.Their lives intertwine as Connie starts courting Eva’s brother, Roger, a bomb disposal expert. In her heart, Connie holds a torch for local artist and freespirit Eugene, but a dark memory from her past makes her wary of trusting any man.The two women are determined to uncover the secrets that have plagued them and kept the two families at war for so long. But can their friendship survive the shocking truth?A moving family drama for fans of Maureen Lee and Katie Flynn.

PAM WEAVER

Pack Up Your Troubles

This book is dedicated to my brother, Barrie Stainer. After a whole life-time apart, it was wonderful to discover your existence. Thank you for your warmth and generosity even though I was such a surprise!

Table of Contents

Title Page (#uccdccbaa-7328-5b01-ad25-fac06ad80ace)

Dedication (#u6e3d69c7-ddd7-5231-8706-35c7d14897a9)

VE Day 1945 (#uf124914c-f622-512f-acc8-cb3ac00b685f)

Chapter One (#ub307c2a5-0765-5693-8789-648bae12fe2c)

Chapter Two (#u15097531-343e-55eb-a0e2-7e109349f061)

Chapter Three (#ud2db3624-f141-5971-8a3f-8811a7673f43)

Chapter Four (#u5e0fbee5-4e8c-54ea-a5f4-e27a2dde0dbd)

Chapter Five (#u601cf7e8-ff79-534c-a1a9-df68165a002c)

Chapter Six (#u93d28992-48bb-5138-9cb3-aebd3b1020a1)

Chapter Seven (#u26cbeb7d-ba60-54ca-a904-9bf84da4f886)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Read on for two exclusive short stories from Pam (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

VE Day 1945

One

By the time they reached Trafalgar Square, the sheer weight of the crowd forced the bus to a standstill. As the passengers turned around, the conductor gave them an exaggerated shrug and rang the bell three times. ‘Sorry folks, but this bus ain’t going no fuver.’

Irene Thompson and Connie Dixon had planned to go on to Buckingham Palace but they had to get off with the rest of the passengers. The bus couldn’t even get anywhere near the pavement but nobody minded. Today, everybody was happy; everyone that is except Connie who couldn’t hide her disappointment.

She had planned to be here with Emmett but he had written a hurried note, which she had stuffed into her shoulder bag as she left the billet. It was terse. ‘Can’t make the celebrations. Mother unwell and she needs me.’ She knew she shouldn’t be annoyed. Emmett was always keen to help others, and he was devoted to his aged mother but it was very galling that he should pick this moment to be noble, just when the celebrations were about to begin. He had said he would telephone her that evening but even if she got back to the barracks in time, she had made up her mind to be ‘out’ when he called. She frowned crossly. Why couldn’t he be like the others? Betty Tanner’s boyfriend brought her flowers all the time and Gloria’s man friend had given her a brand new lipstick. Emmett never did anything like that. It really was too bad.

‘Cheer up, Connie,’ Rene chided as she took her arm. ‘We’re making history. Don’t let Emmett spoil it for you. Be happy.’

As they stepped onto the road, Connie had never seen so many people all in one place. Soldiers, sailors and airmen, from what seemed like every country in the world, had been drawn here to join the people of London to welcome this much longed for day. After five years of war and hardship, peace had come at last. It was rumoured that Churchill and the King had wanted Monday, 7 May to be called VE Day, but the Yanks had insisted that it should be today, Tuesday, 8 May. Connie supposed it was because they were cautious enough to make sure that everything was signed and sealed before enjoying the victory. The German troops had capitulated and signed an unconditional surrender at Eisenhower’s headquarters at 2.41 a.m. Whatever the reason, the grey war-wearied faces had gone and Connie was met with smiles and handshakes from complete strangers. Ever since the news had broken that Adolf Hitler and his mistress had committed suicide, the whole nation finally believed what they had not dared to, that the war in Europe was over at last. The war in the Far East was still raging but the smell of victory was in the air.

The bus had come to a halt because an Aussie soldier, waving the Australian flag, his arm linked with a merchant seaman, was leading a group of revellers down the middle of the street. They were being watched by a couple of eagle-eyed Red Caps but there would be no trouble today. No one was in a fighting mood. The military police were in for a lean time. Even the US MPs – ‘Snowdrops’ as they were known because of their white caps, white Sam Browne belts and white gloves – were redundant. The joyful crowd following in the Aussie soldier’s wake was made up of American GIs, WAAFs, ATS girls and civilians all singing at the tops of their voices.

‘Bless ’em all, the long and the short …’

‘Come on,’ cried Rene as Connie held back, ‘let’s join in.’

An American GI caught Rene’s arm and pulled her into the body of moving people. ‘… this side of the ocean, so cheer up my lads bless ’em all.’

‘Oh Rene,’ cried Connie, ‘it’s really, really over.’

Picking up the lyrics, they lurched with the crowd towards Nelson’s column, the base of which was still covered in hoarding to protect it from bomb blasts even though the last air raid warning had been sounded on 19 March. Someone had stuck a poster on it with ‘Victory over Germany 1945’ on one side and ‘Give thanks by saving.’

Connie nudged Rene in the ribs and jerking her head, shouted over the noise, ‘Give thanks by saving? I should cocoa!’ and they both laughed.

After so much hardship and sacrifice, did the government really think everyone was going to keep on being frugal and sensible with their money? Some might, but not her. She was twenty-one and she’d already spent the best years of her life scrimping and making do, first in the munitions factory and then, after a spell of sick leave, in the WAAFs. Now that the war was over, Connie had no idea what she wanted to do but she was sure of one thing. She was in no mood to save for the future. Hadn’t she just blown all her coupons on her new outfit, a lovely pale lemon sweater and some grey pinstriped slacks? And then there was Emmett. She had hoped he would have asked her to marry him by now, but he hadn’t, presumably because he was anxious about his mother’s health. He’d asked her a few times to go further but Connie had told him she wasn’t that sort of a girl. Still, Rene was right. This was no time to nurse her disappointments. Today was the day to enjoy herself.

In the press of the crowd, Rene was standing on tiptoe to see if anything was happening. ‘We should have got away earlier,’ she grumbled good-naturedly. ‘There’s too many people here.’ Despite the noise all around her, Connie heard a distinct tap-tapping sound just behind her and froze. Someone was tapping his cigarette on a cigarette case. Her blood ran cold and her heartbeat quickened. A surge in the crowd made the woman beside push her and she apologised. ‘Sorry, luv.’

‘Has Churchill given his speech yet?’ Rene asked.

Connie listened hard. The person behind her clicked a cigarette case closed. It couldn’t be … could it? No, it was impossible. It would be far too much of a coincidence.

‘It was supposed to be at nine o’clock this morning,’ the woman went on, ‘but we’re still waiting.’ She rolled her eyes towards the lions. ‘They’ve been putting up speakers so that we can hear him but as for when that happens, your guess is as good as mine.’

‘You all right, Connie?’ said Rene. ‘You look a bit peaky.’

‘Three o’clock,’ said a man’s voice behind them. Connie turned sharply to look at him. Sure enough, he was putting his cigarette case into his inside jacket pocket and was reaching for a lighter. He lit the fag between his lips and took a long drag. ‘That’s what the copper on the steps told me,’ he went on. ‘Three o’clock.’

A wave of relief flooded over her. The man was old, forty or maybe fifty with greying hair and a tobacco-stained moustache. It was all right. It wasn’t him. Connie relaxed and looked at her watch. It was quarter past ten. A group of Girl Guides gathered together at the base of Nelson’s column and were turning around to face the crowd. If the authorities were planning to entertain them, the man must be right. Churchill wouldn’t be giving his speech for ages yet.

‘Rene!’ A girl’s voice rang out above the noise. ‘Rene Thompson, it’s me, Barbara.’

Rene searched the sea of faces and eventually spotted her friend waving as she came towards her. ‘Barbara Hopkins. Well, as I live and breathe. Fancy seeing you here!’

Laughing, the two girls hugged each other. Barbara, dressed in her WAAF uniform, was thickset with very dark curly hair. The girl with her was dressed in civvies and hung back shyly.

‘I haven’t set eyes on you since our training,’ Rene cried happily and Barbara hugged her again. ‘Oooh, it’s so good to see you.’

They stepped apart and introduced everybody.

‘This is Eva O’Hara,’ said Barbara. Eva was tall but with an almost elfin-like face, and a lot of laughter lines around her eyes. She wore dark slacks and a pale blue hand-knitted jumper.

‘And this is Connie,’ said Rene. ‘We share the same billet.’ The hand shaking was soon over and somehow or other the girls had reached one of the fountains in the middle of the square. The day was warm and the water inviting and while Rene and Barbara caught up with old times, Connie, unable to resist, began to roll up the legs of her slacks. ‘Come on,’ she laughed. ‘Which one of you is game for a paddle?’

After a feeble protest from the others, Eva rolled up the legs of her slacks as well. As she climbed in, a sailor gave her a hand and then he rolled up his trouser legs and stepped in. The water was cold, but not unbearable, and it came just above their knees. The sailor and his mate, who joined them, were taller than Connie and Eva so there was less chance of them getting their clothes wet. The sailors were nice looking lads. One had brown Brylcreemed hair and a ready smile and the other one had fairer hair and slightly bucked teeth. He plonked his cap on Connie’s head as they stood together. The blond one carried a knobbly walking stick and Connie wondered if he had some sort of injury, but she didn’t like to ask. They all had to hold on to each other because the bottom of the fountain was covered in algae and a bit slippery. If they weren’t careful, they’d all be under the water and soaked. The singing grew louder.

‘There’ll be blue birds over the white cliffs of Dover …’ The two girls swayed with the sailors as they sang and after a few minutes, the sailor’s cap began to push Connie’s rich chestnut-coloured hair out of place. She wore her hair with curls on the top of her head and pulled away from her face. When her comb landed in the water, her hair fell in attractive loose tendrils around her face. The sailor bent to pick the comb up and at the same time spotted a newspaper photographer taking pictures.

‘Here you are, mate’ he called. ‘Two pretty girls and two good looking sailors. What more could you want for the front page?’

The photographer came over and the sailor planted a kiss on Connie’s cheek as the shutter came down. Connie wasn’t offended but she gave him a playful shove before he was tempted to take any more liberties. She didn’t want Emmett or her own mother to see a picture of her kissing someone else on the front page of the paper and despite the improbabilities, she found herself scouring the faces in the crowd.

‘Which paper are you from?’ laughed Eva as the four of them posed again.

‘Daily Sketch,’ said the photographer before moving on.

Connie heaved a sigh of relief. None of her family read the Daily Sketch and with a bit of luck, her great aunt (they called her Ga) had never even heard of it.

Their legs were getting cold so the four of them climbed out of the water and Connie gave the sailor his cap back. She and Eva only had handkerchiefs to dry their legs but they didn’t care. They held on to each other because in the surging crowd it was difficult to keep a balance on one leg while drying the other. Someone shouted a name, and waving, the two sailors merged back into the crowd.

‘You in the WAAFs as well?’ Connie asked Eva. It seemed very likely considering that her friend Barbara was in uniform.

Eva nodded. ‘And you?’

Connie nodded too.

‘Did you and Rene come on your own?’

‘Actually my boyfriend was meant to be here but he couldn’t come.’

‘Nothing wrong, I hope?’

Connie shook her head. ‘He’s got a sick mother.’

‘I hope it’s not too serious,’ Eva remarked.

Connie shook her head. It was funny that Mrs Gosling always seemed to be ill whenever she and Emmett had something planned but as soon as the thought went through her head, she scolded herself for being so churlish. Nobody could help being ill, could they?

‘No doubt my lot will all be back home and listening to the radio,’ Eva said. ‘My parents are at home and my brother is in the Royal Engineers. He’s still being kept quite busy, and will be for a long time, I’m afraid. He’s in the bomb squad.’

Connie frowned sympathetically. ‘That must be tough on you.’

‘I try not to think about it,’ Eva smiled. ‘What about you? Do you have brothers and sisters?’

‘A brother two years older than me,’ said Connie with a sigh, ‘and a little sister called Mandy. She’s just coming up for six.’

‘What about your brother? Is he in the army?’

Connie shook her head and willed her voice not to crack as she said matter-of-factly, ‘We lost touch.’

Eva stopped what she was doing and looked up. ‘I’m sorry.’

Connie looked away, embarrassed. It wasn’t bloody fair. Families should be together, especially at times like this. Her emotions were all over the place. After her scare of a few minutes ago, now she was fighting the urge to cry. She looked around. ‘Have you seen my other shoe?’

Eva shoved it towards her with the end of her foot.

‘Thanks,’ Connie smiled, glad that Eva hadn’t asked any more questions. She looked at her watch. It was still only 11.30 a.m. If they stayed here, they were in for a long wait and it wasn’t as if Churchill would be coming in person. He was only going to speak over the loudspeakers. Connie blew out her cheeks. She was bored. She wanted something more memorable to happen. Something she could tell her children and grandchildren about when she was old and grey.

‘Let’s go to Buckingham Palace,’ she said suddenly.

Barbara looked around helplessly. ‘Where will we get a bus?’

‘We can walk from here,’ said Eva. ‘It’s not that far.’

They pushed their way back through the crowd and when they finally reached the fringes, all four of them struck out for Buckingham Palace. Rene and Barbara linked arms and walked on ahead so Connie walked with Eva. With a lack of anything else to say, they shared their war experiences.

‘So, where do you come from?’ asked Eva dodging a drunk man staggering along the pavement in the opposite direction.

‘Worthing. It’s on the south coast, near Brighton.’

‘Really?’ Eva laughed. ‘How weird. My folks live near there.’

They could hear the sound of a mouth organ playing, ‘When the lights go on again, all over the world …’ and all at once, an American airman grabbed Eva around the waist and waltzed her into the middle of the road. His companion held out a bottle and leaned into Connie’s face. ‘Hey babe, want some beer?’

Laughing, she pushed him away and another serviceman, this time a jolly Jack Tar, danced Connie into the street next to Eva and the two of them spent a hilarious few minutes with their newfound dance partners. As suddenly as they’d grabbed them, the two men hurried off to join their companions, blowing kisses as they went.

‘Where’s Rene?’ said Eva as they came back together, laughing.

Connie shrugged. ‘No idea,’ she said. ‘I can’t seeBarbara either.’

They stayed where they were for a few minutes but as there was no sign of either of their friends, Connie and Eva struck out on their own. All the way to the palace, they were craning their necks and calling out occasionally but it was hopeless. The crowd was every bit as big as it had been in Trafalgar Square but thankfully, because the area in The Mall was much bigger, they didn’t feel quite so much like sardines. After a while Connie said, ‘This is stupid. We haven’t a hope of finding them.’

‘I think you’re right,’ said Eva, linking her arm through Connie’s. ‘It’s time to give up and enjoy ourselves.’

‘I second that,’ Connie laughed. She suddenly liked this girl. ‘It’s a pity we never got stationed together. I’ve been in Hendon for a while, after I was re-mustered from Blackpool. Were you ever there?’

‘I was stationed along the south coast mostly,’ said Eva shaking her head. ‘Poling, Ford and Rye. That’s where I met Barbara.’

‘I was hoping to be posted to those places,’ said Connie wistfully.

Eva looked sympathetic. ‘Why? Did you have it bad where you were?’

Connie shrugged. ‘Not really.’ It wasn’t that. ‘It was closer to home, that’s all.’

‘We didn’t have too many bombs,’ said Eva, ‘but we were on the front line for the invasion. They were bombed in Poling just before I got there.’

‘I suppose,’ Connie said with a broad grin, ‘as soon as ol’ Hitler heard you were coming, he pushed off elsewhere.’

Eva chuckled.

‘What do you do in the WAAFs?’ Connie continued.

‘Telephone operator,’ said Eva. ‘Mum seems to think it’ll hold me in good stead when I get demobbed. She says I could join the GPO as a telephonist but I’d much rather join the police or something.’

‘Oh no,’ cried Connie. ‘I can’t wait to get out of uniform. I hate it. All those damned buttons to polish, no thank you!’

Eva chuckled.

‘I mean it,’ Connie said defensively. ‘When I went for training in Blackpool, our billet was so damp that every single one of my buttons was green by the morning and that was even after I’d used the button stick and a duster. I had to polish the darned things up again with my uniform cuffs before parade.’

By now, Eva was laughing heartily.

‘You may well laugh,’ Connie continued, ‘but I was forever getting into trouble. There was a constant film over them.’

‘I trained in Blackpool as well,’ said Eva wiping her eyes. ‘1942. I had the choice of factory work or the WAAFs.’

‘I was there in September 1943,’ Connie said. ‘Blowing half a gale on the seafront, it was.’

‘And if your hat blew off while you were marching, you weren’t allowed to stop and pick it up,’ laughed Eva.

‘Yes, and how daft was that?’ Connie remarked.

‘Did you have old Wingate?’

‘You, that gel over there,’ Connie said mimicking Sgt Wingate, the WAAF officer who presided over new recruits, perfectly. ‘Head up, chhh … est out.’ And they both roared.

‘So, what will you do when you get demobbed?’

‘I want to be a nurse,’ said Connie.

‘And they don’t have a uniform?’ Eva teased.

‘Yesss,’ Connie conceded, ‘but it’s much sexier,’ and they both laughed again.

Even after the long walk down The Mall, the crowd outside Buckingham Palace was every bit as good-natured as the crowd had been in Trafalgar Square. People milled about, meeting old friends and new faces with equal enthusiasm. The area around the Victoria Memorial was so overwhelmed with people, you could hardly see the mermaids, mermen or the hippogriff. People sat on the plinths beneath the great angels of Justice and Truth either side of Victoria herself. The statue depicting Motherhood was just as beautiful but it was facing the wrong way. Nobody was interested in what was happening down The Mall. Today all eyes were on the palace.

‘At least he’s home,’ said Eva, rolling her eyes upwards.

Connie turned her head and glanced at the royal standard on the roof, fluttering in the breeze. ‘Oh good-o,’ she grinned as she put on a posh voice. ‘Shall we knock on the door and ask for tea?’ and Eva laughed.

According to one woman in the crowd, the King and Queen had already come out onto the balcony four times so Connie and Eva didn’t hold out much hope that they would be lucky enough to see them. An impromptu conga snaked its way through the crowds and Connie and Eva joined in until they were breathless with laughter.

‘What do you reckon?’ said Eva eventually. ‘Do you want to wait a while?’

‘May as well,’ said Connie with a shrug, ‘now that we’ve walked all this way.’

‘What if we don’t see them?’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ said Connie. ‘At least we were here.’ In her heart of hearts she was hoping they’d be lucky. Two disappointments in one day was too much to bear.

All at once, the cry went up, ‘We want the King, we want the King.’

As it gathered momentum, Connie and Eva joined in. The volume of noise reverberated all around and it felt as if the whole world was stilled by the cry of the crowd. ‘We want the King.’

Dodging one of the few cars still travelling in the area, they crossed the road and joined the people nearer the railings. Connie stared at the imposing building beyond the iron gates and especially at the red- and gold-covered balcony.

‘They say Buckingham Palace has 775 rooms,’ said Eva.

Connie wrinkled her nose. ‘Just think of all that dusting. You’d hardly be bloomin’ finished before you had to start all over again!’

‘Look!’ Eva nudged her arm and Connie’s heart nearly stopped with excitement when a small door within the great centre door opened and a tiny figure in naval uniform came out onto the balcony. The King! King George VI, King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire, and here she was, looking right at him! He raised his arm and with a circular motion of his hand began to wave to the crowd. The Queen in a pale green hat and matching coat and dress had followed him out onto the balcony and when she began to wave as well, the crowd opened its throat and roared. A sea of waving hands and cheering people in front of them, Connie and Eva were carried along with the thrill of it all. In a moment of sudden frustration, Connie stamped her foot. Damn it, Emmett! You should have been here with me, she thought.

Two more figures had joined the King and Queen. Princess Elizabeth in her ATS uniform and Princess Margaret Rose, not yet fifteen and too young to join up, was in a pretty aqua-coloured dress. From where Connie and Eva stood, they were no more than tiny dolls behind the long red- and gold-covered balcony but it was enough. Connie and Eva cheered themselves hoarse.

When eventually the royal family went back inside, the two girls looked at each other with satisfied smiles.

‘I’m starving,’ said Eva. ‘Fancy something to eat?’

‘I’ve got a couple of fish paste sandwiches in my bag,’ said Connie taking it from her shoulder. ‘They’ll be a bit squashed but you’re welcome to share them with me.’

‘Thanks for the offer,’ laughed Eva, ‘but if you don’t mind, I think I can do a bit better than that.’

‘But where are we going to get anything around here?’ Connie cried.

Eva tapped her nose and pulled Connie towards Green Park. When they reached the road, they turned into a side street. Connie hadn’t a clue where she was, but she didn’t feel the least bit nervous. Presently they came across a small crowd laughing and dancing outside a café.

‘Is this where we’re going?’

Eva nodded.

‘How on earth did you know this was here?’

‘My husband’s family has been here for quite a while,’ she said matter-of-factly.

Connie was taken by surprise. Eva had never mentioned a husband. She wasn’t wearing a wedding ring either. She was about to mention it when she was swept up with hugs and kisses and handshakes as the family welcomed Eva’s new friend. Someone called out, ‘Queenie, Queenie luv, look who’s ’ere.’

Queenie, a small woman, middle-aged, with a lined face, hair the colour of salt and pepper and wearing a wrap-around floral apron, came out of the kitchen. The two women looked at each other, unsmiling, then Queenie opened her arms and Eva went to her. Such was the difference in their height, Queenie had to stand on tip-toe and Eva had to lean over, but there was a moment of real tenderness and, Connie supposed, if Queenie was Eva’s mother-in-law, a sense of shared grief. For a moment, Connie felt like an intruder so she looked away. Eva and Queenie went into the kitchen and shut the door.

Another woman sitting at one of the tables touched her arm. Connie looked down and smiled thinly.

‘Why don’t yer sit down, ducks,’ said the woman indicating a vacant chair opposite. ‘They’ll be back in a jiffy.’

Connie nodded her thanks and sat down.

‘Been to the celebrations?’ asked the woman fingering a pearl necklace she had around her neck.

‘To the palace.’

The woman lifted what looked like a glass of milk stout. ‘Here’s to His Majesty, Gowd bless ’im. Did you see him?’

As they talked, Connie discovered that Eva’s mother-in-law, Queenie O’Hara, had lived in London all her life. She and her late husband, an Irishman, had taken over the small café in 1941 after their dockland home had been bombed out of existence.

‘Queenie used to clean ’ouses for the nobs round ’ere,’ said the woman, ‘but when she saw this place was up for sale, it were an hoppertunity too good to miss. He died in ’44 just before her son got married.’ She pointed to a photograph over the counter of an Irish guardsman in his Home Service dress of scarlet tunic and bearskin. ‘That’s her Dermid. The light of her life.’

So this was Eva’s husband. He was certainly a striking man.

‘How long have they been married?’ Connie asked.

The woman shrugged. ‘No more than a couple of weeks.’

Connie frowned. Only a couple of weeks and already Eva had taken off her wedding ring?

‘This damned war,’ muttered the woman. ‘The day he died the light went out of Queenie’s face.’

Connie was appalled. Dead? She looked at the picture of the handsome young man in uniform again. How could it happen? Now she realised that she’d been so concerned to avoid talking about her own troubles that she hadn’t even asked Eva about herself. Losing touch with Kenneth was bad enough but to lose a husband so soon after marriage seemed grossly unfair. And yet coming down The Mall, Eva didn’t seem to be that upset. She was more like the life and soul of the party. Was she callous or was it bravado? But when she emerged from the kitchen and came over to join them at the table, Connie could see that Eva’s eyes were red and she’d obviously been crying. ‘Queenie’s going to rustle something up for us,’ she said matter-of-factly to Connie and then turning to the woman with the pearl beads and the stout, she said, ‘And how are you, Mrs Arkwright?’

Connie’s table companion leaned over and squeezed Eva’s hand. ‘Mustn’t grumble, ducks. Mustn’t grumble.’

Someone in the café had a piano accordion. He squeezed the box and one by one, the songs, especially the one penned during the war to end all wars, the same one which had meant so much to the country for the past five years, filled the air.

‘Pack up your troubles …’

Yes, that’s what the whole world wanted but for the first time that day, Connie felt uncomfortable. The war might be over but people like Eva had to live with the consequences for the rest of their lives. Her mind was full of unanswered questions. How did Eva’s husband die? Was it really only a couple of weeks after they’d been married?

‘What’s the use of worrying?

It never was worthwhile …’

Of course, she couldn’t ask. She hardly knew the girl and it seemed far too intrusive.

‘Pack up your troubles in an old kit bag and

Smile, smile, smile …’ they sang.

Connie could hardly bear it.

All at once, Queenie bustled in from the kitchen and put two plates of meat and veg pie, mash and gravy in front of them. Despite the fact that Connie had to search for a piece of meat in her pie, it was hot, delicious and very welcome.

‘I’m sorry about your husband,’ said Connie as Queenie went off to get them both a cup of tea. Her remark felt lame but she felt she had to say something.

‘You weren’t to know,’ said Eva.

Connie smiled awkwardly and Eva looked away. ‘Not much to say really,’ Eva said, addressing the brick wall. ‘We met in Hyde Park, got married by special licence and he was killed six weeks later.’

Connie stopped eating. ‘But I thought …’ She glanced sideways at Mrs Arkwright who was stubbing out a cigarette. Two weeks or six, it was still terrible. ‘God, Eva, that’s awful.’

Eva ran her fingers through her shoulder-length blonde hair and shrugged her shoulders. ‘It happens.’

She’d only known the girl for a few hours but Connie wasn’t fooled. She might be trying to sound tough but Connie could see that Eva’s eyes had misted over. Connie had obviously reopened an old wound and now she didn’t know what to say. Rescue came once more in the form of Eva’s mother-in-law who reappeared with the tea. Planting a kiss on the top of Eva’s head she said to Connie, ‘Isn’t she lovely? My Dermid picked a real gem. Like a daughter to me she is.’

Connie nodded vigorously and embarrassed, Eva shooed her away with, ‘Get away with you, Queenie.’

‘Now that it’s all over, my gal,’ said Queenie earnestly, ‘you mind you keep in touch.’

‘Of course I will,’ said Eva, looking up and squeezing her hand.

As they finished their meal the man with the accordion struck up ‘A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square’and they all sang along. Or at least, Connie mouthed the words. Her throat was too tight with emotion to sing but the jolly songs had the others dancing and clapping and the more poignant ones brought a sentimental tear to the eye.

‘I presume you’ve got a SOP,’ said Eva. ‘If you need a place to sleep, I’m sure Queenie will put us up, won’t you Queenie?’

‘’Course I can,’ smiled Queenie.

Mrs Arkwright frowned. ‘What’s a SOP?’

‘Sleeping Out Pass,’ laughed Eva.

Connie’s jaw dropped and she gasped in horror. ‘Oh Lord, no! Since we started double summer time, these long light evenings make such a difference. Whatever’s the time?’

‘Eight forty-five.’

‘Oh hell,’ cried Connie grabbing her handbag from the floor. ‘I never gave it a thought. I haven’t even got a late pass and I’ve got to be in by ten.’

‘Where are you billeted?’ asked Eva.

‘Hendon. Can you tell me how to get to the nearest tube station? I shall be all right once I get there.’

‘Doug is going near there,’ said Queenie balancing the empty plates up her arm. ‘He’ll be here in a minute. He can take you in the pig van if you like.’

Connie raised an eyebrow. ‘Pig van?’

‘He collects pig food from all the restaurants around here,’ said Queenie. ‘If you don’t mind the smell, I’m sure he’d give you a lift.’

Connie looked at Eva and they laughed. It was hardly ideal but at least she had the chance to be back to the camp on time.

Connie stood to go. ‘Thanks Eva,’ she said giving her an affectionate hug. ‘I’ve had a wonderful day.’

‘Me too,’ said Eva. ‘We must keep in touch.’

‘I’d like that,’ said Connie.

Her new friend purloined two pieces of paper and gave one to Connie. ‘I’ve no idea where I’ll be when I get demobbed,’ she said, ‘so I’ll give you my mother’s address. She’ll always know where I am.’

‘That’ll be good,’ said Connie writing her own name and address down. ‘I guess it won’t be too hard to meet up. You started to tell me that we lived near each other.’

‘I come from Durrington,’ said Eva handing her details over to Connie. ‘It’s near Worthing.’

‘I know where that is,’ Connie smiled.

Queenie leaned over the counter and interrupted them. ‘Doug’s here, darlin’.’

‘Thanks Queenie,’ said Eva.

‘I’ll tell him you’ll be out in a minute, shall I?’

‘Thanks Queenie,’ said Eva once more. Her mother-in-law went out through the kitchen door.

‘My folks live in Goring,’ Connie smiled. ‘That’s a small village the other side of Worthing.’ She handed Eva her slip of paper and glanced down at the name and address Eva had written down.

Beside her, her new friend gasped. ‘Connie Dixon? You’re not one of the Dixons from Belvedere Nurseries, are you?’

‘Yes,’ said Connie. She stared disbelievingly at the address Eva had just given her. Mrs Vi Maxwell, Durrington Hill. She couldn’t believe what had just happened. She’d spent the day with a girl her family heartily disapproved of. ‘When we met,’ she accused, ‘you said your name was O’Hara.’

‘Of course,’ said Eva, tossing her head defiantly. ‘That’s my married name. I was born a Maxwell, and I’m proud of it.’

‘I had no idea,’ said Connie quietly.

‘I can’t quite believe it either,’ said Eva. ‘And we’ve had such a lovely day.’

Connie nodded. ‘What are we going to do?’

‘Tell you one thing,’ said Eva. ‘I don’t think my mother would be too happy if you turned up on the doorstep.’

Connie’s heart began to bump but she wasn’t sure if she was angry or deeply offended. How could this girl be a Maxwell? She had been so nice. ‘After what your family did to mine …’ she began.

‘After what my family did?’ Eva retorted. ‘I think you’ll find the boot is on the other foot.’

‘Now hang on a minute,’ said Connie, her hand on her hip. ‘I don’t want to get into a fight but get your facts straight first.’

They glared at each other, their jaws jutting.

‘What’s up with you two?’ said Queenie, reappearing in the café. ‘You both look as if you lost half a crown and found a tanner.’

‘She’s been buttering up to me all day and it turns out that she’s a bloody Dixon,’ spat Eva. She turned away and Connie thought she heard her mutter, ‘Cow.’

Connie was livid. ‘It’s hardly surprising,’ she said to Eva’s receding back, ‘that the Dixons and the Maxwells have nothing to do with each other, especially when one of them is so bloomin’ rude.’

Queenie O’Hara looked helplessly from one girl to the other. She seemed confused. ‘I don’t understand. A minute ago you two were best friends. How come things have changed so quickly?’

Connie recovered herself. ‘Buttering up to you all day? What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘You know perfectly well what it means,’ Eva countered huffily. ‘My folks would have leathered me with a strap, if I’d have had anything to do with the Dixons.’

‘Would they really?’ said Connie putting her nose in the air. ‘Well, mine would do no such thing. I’m lucky enough to come from a loving family.’

‘If I had known you were a Dixon, I never would have invited you here,’ cried Eva.

‘Don’t worry,’ said Connie. ‘If I had known you were a Maxwell, I would never have come!’

‘Girls, girls,’ cried Queenie, ‘don’t let this spoil a lovely day. For Gowd’s sake, you’re like a couple of bickering schoolkids. Doug has to get going and you have to say your goodbyes.’

‘Goodbye,’ Eva snapped, carefully avoiding Connie’s eye.

Connie put her nose in the air. ‘Goodbye.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Queenie, shaking her head. ‘Here we are with the first day of peace and you two are at war. Whatever it is, can’t you bury the hatchet?’

‘After what her family did to mine? No, I can’t,’ said Eva. ‘Don’t keep Doug and the pig van waiting, Connie.’ And with that she swept out of the room.

Furious, Connie followed Queenie through the kitchen and out of the back door. Her stomach was in knots. She had really liked Eva and she’d had more fun today than she’d had in a month of Sundays but Eva was a Maxwell. Her emphasis on the word pig hadn’t gone unnoticed either. For a time back there, she had seemed really nice. She could have fooled anyone with that dear friend act she’d put on. Ah well, at least Eva had shown her true colours before it was too late and besides, Connie knew only too well that if she stayed friends with a Maxwell, there would be hell to pay. Hadn’t she been brought up with her great aunt’s stories about the Maxwells? Cheats, liars and vagabonds, the lot of them, according to Ga.

When Queenie hugged her before she climbed into the passenger side of the lorry, Connie hugged her back. It wasn’t Queenie’s fault and her full stomach reminded her that she had been more than generous. Doug turned and gave her a toothless smile as she sat down. He turned out to be a fifty-something in a greasy looking flat cap and leather jerkin.

‘Straight over to Hendon now, Doug,’ said Queenie, closing the passenger door. ‘The girl has to be back by ten.’

‘Right you are, missus,’ said Doug, starting the engine.

As the lorry moved off, Connie caught a glimpse of Eva’s pale face at an upstairs window before she let the curtain drop. At the same moment, Connie screwed up the piece of paper with Eva’s name and address on it and deliberately dropped it out of the van. Queenie’s eyes met hers and Connie felt her cheeks flame. Thankfully, that second, Doug put his foot on the throttle and the van lurched forward.

Doug wasn’t very talkative and Connie was too upset to make much conversation. What a perfectly rotten end to a lovely day. It had started out disappointingly because Emmett couldn’t be with her, but from the moment they had paddled in the fountain, she had had a wonderful time. When Eva had said her family came from Worthing, Connie had no idea of the bombshell that was to come. Her mind drifted back over the years. Now that she came to think about it, her great aunt had never been that specific about the rift between the two families. In fact, Connie hardly knew anything about the Maxwell family, but whenever Ga spoke of them, the contempt in which she held them was written all over her face. She never had a good word to say and when Ga voiced an opinion, no one dared argue. Connie had grown up believing that the Maxwells were dishonest, conniving, deceitful wretches who were to be avoided altogether. Eva was the first Maxwell Connie had ever spoken to and look how nasty she had been when she’d found out who Connie was. She’d certainly shown her true colours, hadn’t she? Ah well, good riddance to bad rubbish.

The cab smelled musty and a bit like a compost heap on a sunny day. After a while it made her feel queasy so Connie was more than relieved to see the gates of her camp looming out of the darkness. She thanked Doug profusely and walked the few hundred yards to the sentry post. She fancied that the guard wrinkled his nose as she walked by and her only thought was to have a good strip-down wash or if she was lucky, a small bath before lights out.

‘Connie! There you are,’ Rene sounded really pleased to see her as she walked in their Nissen hut. ‘Where did you and Eva get to? We looked everywhere for you both but you’d completely disappeared. I’m so sorry. Did you have a terrible time? I mean, you don’t know London at all, do you? Oh, I feel perfectly dreadful about it. How on earth did you get home?’

‘If you’ll let me get a word in edgeways,’ Connie laughed as she threw her bag over her iron bedstead, ‘I’ll tell you.’

As Rene sat on the bed beside her, Connie told her some of what had happened. Listening to her friend’s abject apologies, Connie felt a twinge of guilt. She’d been having such a good time, she hadn’t given Rene and Barbara a moment’s thought since they’d lost sight of each other on The Mall. ‘Please don’t worry,’ she smiled as Rene apologised yet again. ‘It wasn’t your fault. I had a great time anyway.’

‘If you don’t mind me saying so,’ said Rene, pulling a face, ‘you don’t smell too good.’

‘Neither would you if you’d sat in that awful van,’ Connie laughed. ‘Let me go to the bathroom.’

Sitting in the regulation five inches of water, Connie sponged away the smell of the pig food, but somehow she didn’t feel clean. She’d already gone over some of the things Eva had said to her, and now she was remembering the unkind things she had said in return. She shouldn’t have been so sharp with her. After all, Eva was a war widow and being with her mother-in-law again had obviously brought back some painful memories. Hadn’t she suffered enough?

She climbed out of the bath and towelled herself dry. What could she do about it? The Dixons and the Maxwells had been at loggerheads for donkey’s years. She pulled the plug and watched the dirty water swirl around the plughole before disappearing. Wrapping herself in her dressing gown, Connie sighed. There were some stinks that needed a lot more than soap and water to wash them away. Ah well, it was done and dusted as far as she and Eva were concerned. She’d never see her again anyway.

The dream came in the early hours. It was one of those strange moments when you are asleep and you know it’s only a dream and yet you are powerless to wake yourself up. She struggled to make sense of it but as the moving forms in front of her grew darker, the overwhelming fear reached panic proportions. The tap-tapping of the cigarette on that case grew louder. Wake up, Connie. Wake up. Oh God, he was coming for her. Her eyes locked onto his and she couldn’t get the door shut. The door … the door … Now he was inside the room … coming closer and closer. She could smell his breath, feel his hand pinning her shoulders down. Connie, wake up. She was screaming but no sound came from her lips. His rasping voice filled her ears. You’ll like it … He opened his mouth and beyond his yellow teeth she saw his fat, pulsating tongue. She felt that if he came any closer, he would devour her whole. The weight of his body suffocated her. She thrashed her arms to push him away and the rushing sound in her ears grew louder.

‘Connie, it’s all right. It’s just a dream.’ The moment Rene’s voice penetrated the terrifying sounds, they vanished as quickly as someone turning the radio off. Her eyes sprang open and she saw a torch on the pillow beside her. Rene was leaning over her, her hands as light as a feather on her shoulders but she had obviously been shaking her to wake her up. Connie sat up suddenly and blinking in the half light, saw a dozen anxious faces gathered around her bed. At the same time, she became aware that her nightdress was drenched in perspiration and her hair stuck to her forehead.

‘You had a bad dream,’ said Rene. ‘You were shouting out.’

‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘Sorry I woke you all up.’

The girls began to move away and get back into their own beds.

‘Do you want to talk about it?’ said a disembodied voice in the darkness.

Connie lay back on the pillow and shook her head. ‘No, thanks. It was only a dream.’

Two

As Connie staggered through the front gate of Belvedere Nurseries with her suitcase two months later, the dog opened one eye. He was lying across the path, snoozing in the early July sunshine. A mongrel, he had a black and white coat, a feathered tail and more than a touch of the sheepdog about him. When her father had bought him as a pup for her thirteenth birthday, they were told that he was a Border collie, cross retriever but his legs were too short and his mouth lopsided. Connie didn’t care what he looked like; she had loved Pip at first sight. ‘You always did go for the underdog,’ Ga had mumbled in disgust when they brought him home. As soon as the puppy was placed on the mat, he peed a never-ending stream, never once taking his coal black eyes from the old lady’s face. Hiding her smile, Connie knew that like her, Pip had a rebellious streak and they became inseparable. Later on, it was Pip who helped her get over the loss of her father and her brother Kenneth going away like that. She took him for long walks and unloaded her brokenness onto him. When she sat on the grass to cry, he would lick her tears away and wag his tail in sympathy. Although she was careful to obey Ga and never mention ‘that business’, Pip seemed to understand exactly how she was feeling. Pip was her adored companion until she was nineteen years old and joined the WAAFs and he had never quite forgiven her for leaving home. As the gate clicked shut behind her, Connie called out, ‘Here, boy. Here, Pip.’

He rose to his feet, yawned, stretched lazily and she noticed that he was getting quite a few grey hairs around his muzzle. He was nine years old, much more than that in doggie years. She watched him turn around and walk ahead of her to the front door where he waited. When she got to him, Connie reached down and patted his side before ringing the doorbell. ‘Silly old dog,’ she said softly.

As the door opened and her mother stood on the step, Pip came to life, panting and jumping in the small porchway like a thing demented. ‘Connie!’ Gwen laughed as Pip’s joyful barks obviously delighted her. ‘What a wonderful homecoming Pip is giving you.’

‘Warm welcome my eye,’ Connie laughed. ‘He hasn’t even come to my call. He’s doing all that jumping about for your benefit.’

Her mother smiled uncertainly. ‘Well, come on in, darling, let me look at you. I like your new hair.’

‘They’re called Victory curls,’ said Connie patting the back of her head. ‘I have to curl them up with Kirby grips every night and wear a scarf in bed but I think it looks quite nice.’

‘It certainly does,’ her mother enthused.

Gwen Craig was small with high cheekbones and an oval face. Her hair was still dark but Connie could see a few grey hairs and she had tired eyes. It alarmed her to see that her mother had lost weight. Her clothes positively hung on her. Gwen had married Connie’s father Jim Dixon in 1919 when she was only eighteen and bore him two children, Kenneth, now twenty-three, and Connie aged twenty-one. 1936 was an eventful year. First she’d had Pip, then soon after their father had died after a long illness, and Kenneth had left home abruptly. Her father’s illness had sapped them of all their money and because they were living in a tithed cottage, Gwen and Connie would have been homeless if Ga hadn’t come to the rescue. In exchange for housework, Gwen and Connie moved in with her in her small cottage in the same village. A couple of years later, and much to Connie’s surprise, Gwen had married Clifford Craig, a man she had thought was only a nodding acquaintance. Their union had produced Mandy now aged six and the exact image of her mother. Gwen held out her arms and, dropping her case on the mat, Connie went to her.

Behind her, a commanding voice boomed out of the sitting room. ‘Gwen? Is that Constance?’

Connie grinned and ignoring her great aunt’s calls, she deliberately stayed in her mother’s warm embrace for several more minutes. ‘It’s sooo good to see you, Mum.’

‘And you too,’ said Gwen. ‘Where’s Emmett? I half expected him to be with you.’

Connie shook her head. ‘I’m not with him anymore, Mum.’

Her mother looked concerned.

‘It’s all right,’ Connie said quickly. ‘It wasn’t very serious and we lost touch soon after VE Day.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Gwen shaking her head sadly. ‘I thought he seemed like a good man.’

Connie couldn’t argue with that. She had wanted Emmett to get in touch again but it never happened. She had eventually written to his last known address only to have her letter returned to her unopened. Someone had written in the top left-hand corner, ‘Unknown at this address’. Connie had been upset, of course, but what could she do? She had cried. She had gone over and over their last date in her mind, Saturday night at the pictures followed by a fish and chip supper on a park bench, but there was nothing to say why he hadn’t contacted her again. Maybe his mother had taken a turn for the worse, or, perish the thought, maybe she had died. Connie had no idea where she lived so there was little point in fretting about it. ‘Well, it’s all over now,’ she said again.

‘If that’s you, Constance,’ Ga called imperiously, ‘come in here where I can see you.’

Gwen kissed her daughter and let her go, the two of them rolling their eyes in sympathetic unison.

‘Come on,’ her mother smiled, ‘or we’ll never hear the last of it.’

Connie advanced but her mother caught her arm. ‘Shoes.’

Connie bent to unlace her shoes. Pip watched her and Connie patted his side again.

‘You certainly fooled Mum,’ she whispered, ‘but you don’t fool me. We’ll go for a walk later, okay?’ Ignoring her, the dog yawned in a bored way and sauntered towards the kitchen where he flopped into his basket.

‘Hello Ga,’ Connie said cheerfully as she walked into the sitting room.

‘What took you so long?’ said Ga, feigning her disapproval. ‘And what were you whispering about out there?’

‘Mum was asking me about Emmett, that’s all,’ said Connie, ‘and I was explaining that it’s all off.’

Connie kissed her proffered cheek. ‘I can’t say I’m sorry,’ she said into Connie’s neck. ‘I didn’t really take to him.’

Olive Dixon was a formidable woman. She was solidly built with spade-like hands from working the small market garden, which brought in the lion’s share of the family income. Unlike most women of her age, her sunburnt face was relatively free of wrinkles and she wore her steel grey hair piled on the top of her head in a flat squashed bun.

‘What the devil have you done to your hair?’ she frowned.

‘Don’t you like it?’ said Connie.

‘Indeed I do not,’ said Ga. ‘With all those silly curls you look like something out of a Greek tragedy.’

Connie chose to ignore her. Usually when Olive said jump, everybody said, how high. Ever since Gwen and Connie had come to live with her after Jim Dixon died, she had quickly established herself as the undoubted head of the family. When Clifford and Gwen married in 1938, he had tried to exert his authority, but at a mere five feet, Olive towered over everybody by the sheer force of her personality. They had moved from Patching to Goring to make a completely new start but because Ga had bought the Belvedere Nurseries and the house they all lived in, Gwen and Clifford were expected to run everything, while she remained firmly in charge.

‘I’ll get the tea,’ said Gwen, leaving the room.

Ga was sitting at her beloved writing bureau and Connie noticed for the first time that her right leg was raised up on a pouf. Her knee was very swollen.

‘Ouch, that looks painful,’ said Connie reaching out.

‘Don’t touch it!’ Olive cried. ‘I’m waiting for Peninnah Cooper.’

Connie took in her breath. ‘The gypsies are here?’

‘They turned up about a week ago,’ said Olive. ‘Reuben parked the caravan down by the lay-by near the field.’

‘And Kez?’

Ga pursed her lips. ‘I never did understand why you wanted to hang around with that ignorant girl. Yes, she’s here too. She’s married now, with children.’

Connie was thrilled. She couldn’t wait to see her old childhood friend. Kez a wife and mother … Imagine that …

The gypsies had been a part of her life as far back as she could remember. When the family lived at Patching, they had turned up at different times of year to work in the fields.

The Roma like Kez and Peninnah had no time for other travellers like the fairground showman, the circus performer or the Irish tinkers, because they felt they had given them a bad name. The Roma were in a class of their own. Normally they didn’t even mix socially with Gorgias, a name they gave all house dwellers, which is what made Kez and Connie’s friendship all the more unusual. They had met as children during the short periods of time that Kez went to Connie’s school. Because Kezia’s parents always kept to the familiar patterns, Connie would wait in the lane in early May when the bluebells came out in profusion in the local woods. Kezia and her family would pick them by the basketful, tie them into bunches held together by the thick leaves and hawk them around Worthing. Connie was allowed to help with the picking and tying but her father drew the line at selling what God had given to the world for free. It was always a bad time when the season was over, but Kez would be back in the autumn to harvest in the local apple orchards.

Everything changed in 1938. Kezia’s mother had died, old before her time. Then there was that business with Kenneth, after which Connie’s mother married Clifford and they had moved to Goring.

‘Why is Pen coming?’ Connie asked.

‘She’s bringing a couple of bees.’

Connie raised an eyebrow. ‘A couple of bees?’

‘For my knee,’ said Olive impatiently. Ga feigned disapproval of the gypsies until it suited her to call upon them.

Peninnah Cooper, Kez’s grandmother, was well known for her country cures and many people swore by them. They may have been part of a bygone era but funnily enough, Pen’s ‘cures’ often worked. All the same, Connie couldn’t imagine how bringing some bees could help Olive’s bad leg.

She heard the sound of tinkling cups and her mother came in with the tea trolley. Connie took off her coat and sat down. Teatime in the Dixon household was always a cosy affair and today her mother had tried to make it a bit special. She had got out the willow pattern tea service and the silver spoons Ga had kept in the top drawer. Connie appreciated her mother’s effort. ‘Thanks Mum,’ she smiled.

Whenever she was homesick, Connie used to picture this little ritual. Gwen put the tea strainer over the cup and poured the tea. When the first cup was full, Connie handed it to Ga.

‘So,’ said Olive, ‘now that you’re finally out of it, we’ll be glad of your help in the nursery.’

Connie winced. She had stayed on in the WAAFs for an extra couple of weeks because there had been a lot to do in the aftermath of the war. As well as doing her usual general office duties, her work had mainly been making sure that war-damaged RAF personnel were being followed up and getting help from the right channels. Not that there was a lot she could do. Most men were simply discharged and left to get on with it, something which left her with a yearning to do something constructive with her life.

‘Actually,’ said Connie taking a deep breath, ‘I’ve made some plans of my own. I’ve decided that I want to be a nurse.’

She knew they’d be surprised but Gwen almost dropped her teacup and Ga’s mouth fell open. ‘A nurse?’ she said in a measured tone. ‘Do you think you have the stomach for it?’

‘I’ve toughened up a lot because of the war,’ said Connie.

‘We really need another pair of hands on the smallholding,’ said Ga, glancing at Connie’s mother.

‘We’ll manage,’ Gwen smiled.

‘Manage?’ Ga challenged. ‘It’s hard enough to cope now. Your mother and I are not getting any younger and we’ll need every pair of hands we can get.’

The nurseries weren’t large by the standards of other nurseries in the area. They grew seedlings and vegetables and her mother kept hens for the eggs. There were a couple of stretches of waste ground which had never been developed but there was plenty of work to be done. Connie knew that if she stayed at home she would be expected to work in the small lean-to shop attached to the side of the house or in the greenhouse. She didn’t mind helping out, but she certainly didn’t want to do it for the rest of her life and besides, she wasn’t sure the nursery could support so many people.

Connie sipped her tea. She’d always known it would be a bit of a job persuading Ga and her mother that she wanted a career of her own. She wasn’t afraid to go ahead with or without their blessing, although she would much prefer them to be happy to let her go. She was determined to stand her ground, come what may. She was nearly twenty-two for heaven’s sake. The war had changed everything. Girls had more opportunities than they’d ever had before, and besides, now that Emmett was out of the picture what else was there? She didn’t want to leave it any longer. The training took four years. By the time she’d finished, she would be twenty-six … quite old really. Ga’s reaction was predictable but it took Connie by surprise that her mother didn’t put up more of a fight.

Pip barked.

‘That’ll be Mandy, home from school,’ said Gwen as the dog hurried outside. Connie’s younger sister Mandy had been at infants’ school for about a year. ‘Mrs Bawden, next door, and I take it in turns to take Mandy and Joan to school. It’s her turn this week.’

Connie stood up as Mandy burst through the door and threw herself into her arms. ‘Connie, Connie!’ Laughing, Connie twirled Mandy around in a circle.

‘How many times do I have to tell you, Mandy?’ Olive grumbled petulantly. ‘No outdoor shoes in the house.’

Connie let her go and Mandy slid to the floor. Obediently the little girl retraced her steps to the back door and took off her shoes, placing them next to the umbrella stand. Connie caught her breath. With her hair in plaits and wearing a grey pinafore and white blouse her little sister looked so grown up.

A couple of minutes later, Pen Cooper knocked on the door and stepped into the house. She had a jam jar in her hand. Inside the jar, an angry bee knocked itself against the glass. Pen was not only a gypsy but she was also a bit of an eccentric. She wore a long flowing dress and plenty of beads. She had make-up too, which was unusual for a traveller. Thickly layered powder and some kohl around her pale mischievous eyes. When she saw Connie she stopped and held out her arms. ‘’Tis good to see ye.’

‘It’s good to see you too, Pen,’ Connie smiled. ‘I’ll come up later and see Kez if that’s all right.’

‘You knows it is,’ Pen beamed, ‘and welcome.’ She turned her attention to Olive. ‘Now, are you ready, dear?’

‘As ready as I’ll ever be,’ said Olive. ‘It’s killing me and someone’s got to get the ground ready for the calabrese and winter cabbages.’

Connie saw her mother’s back stiffen.

‘Yoohoo.’ They heard another voice call from the front door and Aunt Aggie came into the room. Aunt Aggie wasn’t really a relation but she was Ga’s oldest friend. A rather prim woman, Aggie never had a hair out of place. She always seemed to be dressed in her Sunday best and today was no exception. She wore a yellow floral dress, white peep-toe shoes, newly whitened, and she carried a white handbag. She and Olive had been friends since they were at school together. Peeling off her white crochet gloves, Aggie offered Connie a cold cheek to kiss. ‘How nice to have you home again.’

‘I’d better make a start,’ said Pen and Gwen took a protesting Mandy away from Connie’s arms and upstairs to get changed out of her uniform. ‘But I want to see, Mummy. Why can’t I watch?’ They could hear her complaining all the way to her room.

Connie watched fascinated as Pen took some tweezers from her pocket. ‘Ready?’ she said again and slid the lid from the jar.

‘Are you sure about this Olive, dear?’ Aggie asked.

‘Pen knows what she’s doing,’ Olive snapped.

Aggie poured herself a cup of tea and sat down with one leg swinging as she crossed it over the other. The bee continued to bang itself against the jar until eventually Pen caught its wings with her fingers and put it onto Olive’s swollen knee, holding it there until thoroughly enraged, it stung her. Olive winced. Pen removed the dying bee and eventually the sting it had left behind.

Gwen reappeared at the door. ‘While Mandy is getting changed, I’m going outside for a bit.’

Connie left the three women to watch Ga’s swelling knee and followed her mother outside to where she found her picking runner beans.

‘There’s so much to do this time of year,’ she said matter-of-factly as Connie made a start on the broad beans in the next row. Their smallholding was very popular and the shop was always busy. Their customers knew everything was very fresh, perhaps only just picked. Olive kept the prices down while Gwen did her best to keep the supplies from running out, in between the housework and looking after Mandy. Connie knew how hard her mother’s life was and the unease slipped in.

‘You don’t mind me not working in the nursery, do you Mum?’

‘I’m pleased you’re going to make a career for yourself, dear,’ said Gwen. ‘You’ll make a good nurse.’

‘Ga was a bit cross,’ said Connie. ‘I don’t want to leave you in the lurch.’

‘We’ll be fine,’ said Gwen.

The nursery was hardly making its way when Olive bought it but Clifford was such an excellent nurseryman that he had pulled it back from the brink and made it a going concern. When he was called up in 1943, the two women took over. Gwen used to serve in the shop, but these days she preferred to work on the land, leaving Ga to look after the business side of things. It was never voiced, but the arrangement was so much better since Olive’s knee started playing up. On bad days, Olive could sit in the shop, which was little more than a glorified lean-to, and let the customers serve themselves.

Although the family managed to lift the early potatoes themselves, they generally hired casual labourers to help with the main crop in September. They mostly used the locals because the gypsies didn’t often come this way. When Connie was a child and the gypsies came to Patching, she and Kenneth were invited to share in their communal meal. Connie loved it, especially when Peninnah, Kez’s grandmother, would take her pipe out of her mouth and tell them about the old days. She had an encyclopedic knowledge when it came to family and some of them sounded such wonderful people. ‘They called ’e Red shirt Matthew on account as he always wore a red shirt …’ ‘So they stuffed the two rabbits under ’is big ol’ hat and legged it all the way ’ome …’ ‘She’d stolen ’is trousers, so when ’e got out of the lake, ’e was as naked as the day he were born. He had to walk ’ome without a stitch on ’is back.’ Pen would stop to chuckle. ‘That learned him not to mess about with a gypsy girl …’ Connie and Kenneth would roar their heads off even though they hadn’t a clue who she was talking about. Nobody minded the gypsies being there back then. They were hard workers, the women and children selling handmade pegs and bunches of flowers around the centre of Worthing and the men doing any kind of manual labour on offer.

The war had changed everything. The government had created the Land Army pushing the gypsies further to the fringes of society perhaps, but the hope was that if the powers-that-be disbanded it, farmers would use gypsy labour once again. However, the fate of Kezia and her family was not Connie’s main concern right now. As they worked side by side, she noticed how tired her mother looked.

‘I’m fine,’ said Gwen when Connie remarked on it. ‘I’ve had a bit extra to do with Ga being laid up but things are easing up a bit now. We’ve taken on a local girl to work in the shop, and Clifford will be demobbed soon.’

‘Have you been to the doctor?’

‘Connie, I’m fine,’ Gwen insisted.

Connie knew better than to argue. ‘When’s Clifford coming home?’

‘At the end of the month.’

Connie breathed a silent sigh of relief. With Clifford back, he could take some of the workload off Mum and she could begin her training at the hospital in September as she had planned. She relaxed as she carried on picking. ‘What’s she like?’ Connie asked.

‘Who?’

‘The girl in the shop.’

‘Sally? She’s a bit scatty at times but a good worker,’ said Gwen, her bowl now full. ‘The runner beans have been really good this year.’

Mandy had come out of the house and begun skipping. Connie watched her half-sister and was impressed.

‘She’s only just learned how to do it,’ said Gwen proudly. ‘I think she’s quite good for someone not quite seven, don’t you?’

There was a movement by the back door and Peninnah appeared with Ga. Olive was limping and she had to hold on to the doorposts to keep herself steady but at least she was mobile again. Her leg was heavily bandaged. The two women said their goodbyes and Pen blew a kiss to Mandy.

As she watched her great aunt turn around in the doorway and walk painfully back indoors, Connie turned back to the job in hand. The two boxes were full, one with runner beans and the other with broad beans in the jackets as they headed towards the shop. As they took the supplies inside, Connie met the girl working there.

Sally Burndell was a pretty girl with dark hair and full lips who made no secret of the fact that she was going to go to secretarial college later in the year and was only in the shop for a short while. Connie liked her directness. They arranged the fresh beans underneath the beans already in the boxes to make sure the older beans picked the day before were sold first. Gwen went round picking out failing fruit and vegetables and making sure the supplies were topped up. Connie fetched some fresh newspaper from the storeroom and showed Sally how to make it into bags by folding them a certain way. She also got her to fan out the paper wrapped around the fruit in the orange boxes.

‘Press them flat and put them in a pile,’ said Connie.

‘Whatever for?’ said a voice behind them.

Connie turned to see Aunt Aggie watching them from the doorway.

‘They could be used as toilet paper,’ she said. ‘It’s a lot softer than newspaper. It’s a tip I picked up from the WAAF.’

‘Huh!’ Aunt Aggie scoffed. ‘What’s wrong with newspaper?’

‘I must go in and get the tea,’ said Gwen, wiping her hands on a towel.

‘And I’m off for the bus,’ said Aggie turning to leave. ‘Olive said I could have some beans. Not too many. There’s only me.’

Sally wrapped a few runner beans in newspaper and handed them to her. Aunt Aggie took them without a thank you.

‘See you soon, Aggie,’ Gwen called.

They watched her go.

‘When you’ve got a bum as big as hers,’ Sally said, ‘I guess you’d need a newspaper as big as The Times.’

‘Shh,’ Connie cautioned. ‘She’ll hear you.’ But she and her mother couldn’t help giggling.

Thankfully, Aggie hadn’t heard the remark because she walked on.

‘Play with me, Connie,’ Mandy pleaded as Connie followed her mother outside.

Gwen turned around. ‘No need for you to come into the house,’ she smiled. ‘I’ve made a sausage in cider casserole. All I have to do is take it out of the oven. Stay here and play with Mandy.’

The two sisters grinned. Mandy flicked her plaits over her shoulder and before long, Connie was holding the rope and they were skipping together. Connie hadn’t done this for years. She was a bit out of breath but she hadn’t lost her touch. Pip wandered outside.

‘When I was little,’ she told Mandy, ‘I used to tie the rope on the down-pipe like this and when I turned it, Pip would join in.’

As soon as she said it, and much to Connie’s delight, he joined in. Mandy clapped her hands in delight. By the time their mother called them for tea, she, Pip and Mandy had become great friends.

Three

Teatime over, Connie tucked Mandy up in bed and after a bedtime story they sang her favourite song, ‘You Are My Sunshine’. It was a precious time for both of them and one that Connie had started when her little sister was very young. Every time she’d come home on leave, Mandy had begged her to sing it as she said goodnight. Connie crept out of Mandy’s room and had what her mother would call a cat’s lick in the bathroom and changed her clothes. She put on the pale lemon sweater and same grey pinstriped slacks she had worn in Trafalgar Square and after calling out her goodbyes, headed in the direction of Goring-by-Sea railway station. Pip invited himself along with her, sometimes running on ahead, occasionally stopping to sniff something. She watched him scenting a blade of grass, a telegraph pole and the postbox and marvelled at his carefree love of life.

They reached the Goring crossroad and walked up Titnore Lane. All at once the dog stopped and motionless, sniffed the air, then he took off at breakneck speed. A few minutes later she could hear him in the distance barking joyously. Connie quickened her step and as she rounded a small bend in the lane, she saw them – the gypsies. By now Pip was hysterical with delight, jumping from one to the other, his tail wagging as he let out little yelps of pleasure. Connie was surprised. The dog had only been a puppy when he’d last seen the gypsies but he clearly remembered them.

Connie could pick some of them out even from here. Peninnah Cooper, Kez’s maternal grandmother was stirring something in the black pot hung over an open fire, and was that Kez’s cousin sitting on the caravan steps? Reuben Light, Kez’s father, his frail old body bent low with arthritis and it seemed that he had developed an unhealthy cough. Reuben spotted her and stood up to wave but where was Kez?

Connie recalled how devastated she had been when her mother and Ga moved to Goring in 1938. How would Kez know where she was? Writing a letter was hopeless. For a start, what would she put on the envelope? ‘To the gypsy caravan somewhere near Patching pond in May’ hardly seemed appropriate and besides, Kez couldn’t read. Connie had wept buckets at the injustice of it all, which was why the fact that Kez was just down the road from where she now lived after all this time was so amazing.

There was a movement by the caravan and there she was. She had a baby in her arms but as soon as she saw Connie, Kez called out her name and pushed the child into Pen’s arms. Connie broke into a run. The two women met in the lane and flinging their arms around each other they danced in circles, laughing as they went. Kezia smelled of rosemary and lavender, her flaming red hair tied untidily with a green ribbon flapped behind her as they spun together. She was wearing a long floral dress with a tight bodice and loose unlaced boots. They broke away and held each other at arm’s length to look at each other and the questions flew. How are you? You look great. Is that your baby? How long has it been since we met? It must be eight, nine years … Where have you been all this time? A little boy had joined them and was tugging at Kezia’s skirt. She bent to pick him up, settling him comfortably on her hip. As they wandered towards the caravan a delicious smell of rabbit stew wafted towards her.

‘Stay and eat with us,’ said Kez.

Connie linked her arm in Kezia’s. Oh, it was good to see her again. ‘I’ve just eaten but I’d love to share a cuppa.’ She smiled at the child on Kez’s hip. ‘And who is this?’

‘This is my son, Samuel,’ Kez beamed. ‘He’s nearly three. Say hello Sam.’ But the child turned his head shyly into his mother’s neck.

‘Pen told me you had kids,’ said Connie. ‘But two?’

‘I had three,’ said Kezia, her voice becoming flat. ‘Pen is holding the babby but my little Joseph went to be with the angels.’

‘Oh Kez, I’m so sorry,’ said Connie suddenly stricken for her.

When they reached the caravan, there were more greetings and now that she was up close to him, Connie could see that Reuben was but a shadow of his former self. All the same, he was delighted to see her. ‘It must be ten year since I laid eyes on ye,’ he smiled, his gold tooth flashing in the failing evening sun.

‘Nine,’ Kezia corrected.

‘It does seem a long time ago, doesn’t it?’ said Connie shaking the old man’s hand.

Behind Reuben’s traditional gypsy caravan, she caught a glimpse of a long motor trailer, an ex-army vehicle. Kezia explained that using his army pay, her husband, Simeon, had just bought it for the family and now he was converting it into their home.

‘He says it’s the way of the future,’ said Kez proudly.

Other members of the family, including Kezia’s husband, Simeon (how they all loved their Old Testament names) tumbled out to greet Connie respectfully. If they seemed a little surprised that a Gorgia would be joining them as they ate, they said nothing. Reuben offered Connie an upturned box and as she sat down a sullen-faced lad came out of the trailer.

‘Isaac!’ Connie cried. There was about six years between them so Kezia’s baby brother was about fifteen or sixteen now. She remembered how when he was a year or so old, the two girls had taken it in turns to hoick him on their hip as they played together. He looked a lot like Kez. He had the same flaming red hair which was tousled and untidy but he was fresh-faced. He wore a kerchief at his neck and his shirt was open to reveal his hairless chest. Isaac’s greeting was polite but nowhere near as enthusiastic as his sister’s. As always, the men ate first.

As she sat by the campfire, Connie couldn’t help reflecting how different their lives were. Kez looked much older than her twenty-two years. Her hands were calloused from potato picking and Brussels sprout harvesting in the winter. At this time of year, her fingers were already stained bright red from picking strawberries and raspberries.

As is the custom with Romani gypsies, Kez had married young. The strict ethics of their culture demanded that all girls marry between sixteen and eighteen. She had to be a virgin and according to the code, she was only allowed a maximum of four suitors. Any more and she would be considered too flighty. Simeon, Kezia’s husband, had been her one and only suitor and she’d married him just before her seventeenth birthday.

As the baby finished feeding Kez looked up, giving Connie a shy smile. She sat her baby up to wind her and then handed her to Connie. ‘What did you call her?’

‘Blossom.’

‘I don’t recall a Blossom in the Bible!’

‘Well, that’s where you’re wrong, Connie Dixon,’ said Kez. ‘The day my daughter first drew breath Pen told Simeon, “It shall blossom abundantly, and rejoice even with joy and singing,” and that’s in the Bible that is.’

‘You’re kidding,’ Connie gasped.

‘Isaiah 35, Verse 2,’ said Kez adopting a superior tone.

Connie burst out laughing and Kez joined in. Looking down at this pretty green-eyed baby with wisps of bright red hair, her name suited her perfectly. She was small but sturdy. She would need to be. The life of a gypsy was hard. Kezia and her family were constantly on the move. They had always gone wherever there was picking to be done, setting up camp in some field belonging to the farmer in question. As each season came and went, they went on to the next place. It sounded idyllic, waking with the dawn and hitching the horse to the wagon to head towards the next source of work, but Connie didn’t envy them.

Sam had found a ball and he and Pip began a game of toss and fetch. The gypsy dogs, tied to the fence post, could only look on enviously and the pair of them giggled and barked together. Connie sighed. If only life were always this simple, this pleasurable.

Connie had been around Kez and her family enough times to know that contrary to a commonly held belief, the true gypsy was not dirty. She watched as Kez scrubbed her little boy before getting him ready for bed. She worked so hard on him the child began to protest. After changing her baby’s nappy, one of the other women took them both inside the long trailer to put them to bed, giving the two friends time together to catch up with their news.

As soon as he had eaten, Reuben was ready to sleep. He never slept inside the caravan because that was purely to house his possessions. Instead, he crawled inside a small tunnel tent pitched on the grass verge beside it and said his goodnight. As he laced the front of the tent, Connie listened to him coughing.

‘He’s not so good,’ said Kez quietly, as if reading her thoughts. Connie nodded. What could she say? Life on the road was hard on them all. Sleeping out in the open when you’re unwell wasn’t ideal but it was no good suggesting that he should go indoors. The open air and the freedom of the road was all Reuben knew.

‘Has he seen a doctor?’ Connie asked.

‘He won’t go to a doctor,’ said Kez with a shrug. ‘He says all doctors are Gorgias and not to be trusted.’

‘Doesn’t it get any easier?’ Connie asked. ‘Being on the road, I mean?’

Kezia shook her head. ‘Sometimes, even before we unhitch the horse, the village bobby comes along on his bicycle to tell us to move on.’

‘Couldn’t you refuse?’

‘If we do they threaten to take our children away and put them in a home.’

Connie was appalled. ‘Can they do that?’

Kez shrugged. ‘So they say.’

Connie shivered. The sweater only had short sleeves and she was getting cold now. She wished she’d brought a cardigan. ‘I’d better be getting back,’ she said.

‘You didn’t get your tea yet,’ said Kez.

Connie sat back on the caravan steps and sipped the scalding hot tea. Kez must have noticed her shivering because she threw a shawl over her shoulders. As Kezia ate, Connie told her about life in the munitions factory and the WAAF. Kez told Connie about the day her mother died and the loss of her little Joseph. On a happier note, she told Connie about meeting Simeon and of their marriage. Simeon, who had joined up during the war, had only just returned to her. He had adjusted to life with the Gorgia and, she said proudly, ‘He did his bit.’

‘Simeon talks of buying land,’ Kez went on. ‘He wants us to settle down.’

Connie was sceptical. ‘But you’ve always enjoyed moving around. Will you be able to settle in one place?’