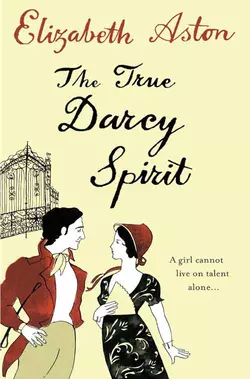

The True Darcy Spirit

Elizabeth Aston

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 503.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A richly entertaining novel about the next generation of Darcy girls, perfect for fans of Jane Austen and Georgette Heyer.Cassandra, a young cousin to the children of Mr and Mrs Darcy of Pride and Prejudice is a worthy heir to them in every way: she speaks her mind, is witty, shrewd and talented. But her impulsive behaviour leads her to make one very major mistake. Cast out of her respectable place in the world, she is determined to make her own way. But in a London that regards an attractive and independent young lady with deep suspicion, how can she avoid coming upon the town?The True Darcy Spirit will appeal to all readers who’ve seen the films, reread the originals, but still want more!