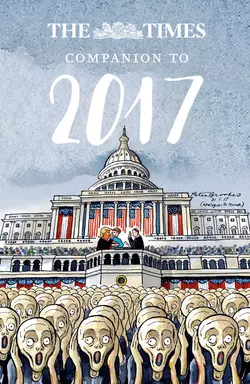

The Times Companion to 2017: The best writing from The Times

Ian Brunskill

A year of political upheaval, sporting thrills, and continuing global conflict. The Times Companion to 2017 is a selection of authoritative and entertaining writing on politics, war, culture, sport and current affairs from the world’s most famous newspaper.No dry chronicle of daily events, it brings together some of the best articles – and photographs and graphics – published by The Times between September 2016 and August 2017. In a lively mix of news features and reportage, profiles and interviews, opinion columns and expert analysis, The Times’ award-winning journalists tell the stories behind the headlines of a remarkable year.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_52cb30d0-8032-52f2-9ac1-a24ec685efcb)

Published by Times Books

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Westerhill Road

Bishopbriggs

Glasgow G64 2QT

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

times.books@harpercollins.co.uk (mailto:times.books@harpercollins.co.uk)

First edition 2017

© Times Newspapers Ltd 2017

www.thetimes.co.uk (http://www.thetimes.co.uk/)

The Times® is a registered trademark of Times Newspapers Ltd

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

The contents of this publication are believed correct at the time of printing. Nevertheless the publisher can accept no responsibility for errors or omissions, changes in the detail given or for any expense or loss thereby caused.

HarperCollins does not warrant that any website mentioned in this title will be provided uninterrupted, that any website will be error free, that defects will be corrected, or that the website or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or bugs. For full terms and conditions please refer to the site terms provided on the website.

eBook Edition: © October 2017

ISBN: 9780008262648

Version: 2017-10-12

CONTENTS

Cover (#u3259de67-747b-517b-b4ca-fe1b16458ff3)

Title Page (#u95a6b109-aa99-564b-8e23-5d59d97e1508)

Copyright (#ulink_56f97b7d-6f6c-5037-893c-0ca5246d8652)

Introduction — Ian Brunskill (#ulink_15a8cc22-6e42-59bc-9818-7312a07558e3)

Acknowledgments (#ulink_cd85c837-3e3e-55a0-8363-5c61731cad72)

AUTUMN (#ulink_f8018ab0-6842-59bf-abde-7e9d20bc1d70)

Meritocracy is the last thing Britain needs — Philip Collins (#ulink_cae9237c-2fb1-5462-8056-a493d1c62f0a)

Jeremy Paxman: ‘I’m not ashamed to say I’ve suffered depression’ — Interview by Janice Turner (#ulink_1d8fdb94-35f4-5533-bd2b-028985539196)

Bataclan: one year on — Adam Sage (#ulink_0a8b4705-0ea6-5111-8645-27ba49dde38f)

You can’t trust the people with democracy — Roger Boyes (#ulink_0ada2856-5ebf-5d35-bcaf-af845b895492)

Burnt and tortured migrants filled decks as we rushed to help — Bel Trew (#ulink_4669e91c-7829-5347-9df7-8a5458a657f8)

‘Tantrums and shocking racism’ of inquiry’s dysfunctional dame — Andrew Norfolk, Sean O’Neill (#ulink_0b5e428f-9cfa-5f46-8a86-d6ef0889c72f)

Middle-aged virgins: Japan’s big secret — Richard Lloyd Parry (#ulink_4b993533-d1c8-5b5b-b7fd-aa37f590da57)

Royal family are more secretive than MI5 — Ben Macintyre (#ulink_767898dc-0f6e-5f94-b99d-030c9d535b42)

Inside Britain’s only transgender clinic for children — Louise France (#ulink_a61af42b-7555-5269-9785-06a08fc4eab6)

A bare-knuckle fighter in the bloodiest contest ever — Rhys Blakely (#ulink_6a03658f-75f8-5dc5-ba39-c4d6cc89a7cc)

Leonard Cohen — Obituary (#ulink_06d1f97c-fb5f-5939-bc24-7229bb9b7bd1)

Let’s stop being so paranoid about androids — Matt Ridley (#ulink_64698a8b-15a7-5794-898b-32b2b79e2b9e)

WINTER (#litres_trial_promo)

Game’s soul is not at Lord’s. It is here — Mike Atherton (#litres_trial_promo)

Confessions of a middle-aged man — Jonathan Gershfield (#litres_trial_promo)

Terrible teaching is what makes Oxford special — Giles Coren (#litres_trial_promo)

Children killed in Duterte’s drug war — Richard Lloyd Parry (#litres_trial_promo)

Zsa Zsa Gabor — Obituary (#litres_trial_promo)

Cash belongs in the past so let’s abolish it — Ed Conway (#litres_trial_promo)

Wild swimming is a rare splash of freedom — Edward Lucas (#litres_trial_promo)

Children of the internet are happy to live a lie — Oliver Moody (#litres_trial_promo)

How I conquered my morbid fear of flying — Melanie Phillips (#litres_trial_promo)

Year of revolution — Leading Article (#litres_trial_promo)

The NHS is in need of emergency treatment — Janice Turner (#litres_trial_promo)

The hedgie with a 99.9% success rate — Harry Wilson (#litres_trial_promo)

Are you tough enough for ‘radical candour’ at work? — Helen Rumbelow (#litres_trial_promo)

Our week: everyone — Hugo Rifkind (#litres_trial_promo)

Tourist exodus leaves gigolos hungry for love — Jerome Starkey (#litres_trial_promo)

Big brands fund terror — Alexi Mostrous (#litres_trial_promo)

Being offended is often the best medicine — David Aaronovitch (#litres_trial_promo)

Our magical Wembley moments — George Caulkin (#litres_trial_promo)

Spinal column: I keep seeing the ghost of Melanie past — Melanie Reid (#litres_trial_promo)

SPRING (#litres_trial_promo)

Scraps, storms and trench hand all in a 23ft boat — Damian Whitworth (#litres_trial_promo)

We all need to learn how to talk about death — Alice Thomson (#litres_trial_promo)

What’s a nice Asian boy doing in a place like this? — Sathnam Sanghera (#litres_trial_promo)

Giving birth is a lethal gamble in Venezuela — Lucinda Elliott (#litres_trial_promo)

Chuck Berry was a political revolutionary — Daniel Finkelstein (#litres_trial_promo)

On Westminster Bridge — Leading Article (#litres_trial_promo)

It’s time to reclaim our rights from big tech — Iain Martin (#litres_trial_promo)

Our addicts turn blue, then they die: the town at the centre of new US drugs epidemic — Rhys Blakely (#litres_trial_promo)

This is the end of democracy, cry protesters as nation splits in two — Hannah Lucinda Smith (#litres_trial_promo)

Drought casts the shadow of death — Catherine Philp (#litres_trial_promo)

Nepal is back: ancient temples, mountains and Bengal tigers —Tom Chesshyre (#litres_trial_promo)

Le Pen can be president if she plays the long game — Giles Whittell (#litres_trial_promo)

Duke retires rather than grow frail in public — Valentine Low (#litres_trial_promo)

Landslide for Macron — Charles Bremner, Adam Sage (#litres_trial_promo)

Giving a voice to the lost girls of Rochdale — Andrew Norfolk (#litres_trial_promo)

Queer City by Peter Ackroyd — Review by Robbie Millen (#litres_trial_promo)

Watch out — here come the Bridezillas — David Emanuel interviewed by Hilary Rose (#litres_trial_promo)

The 10 worst crimes in horticulture — Ann Treneman (#litres_trial_promo)

Shock poll predicts Tory losses — Sam Coates (#litres_trial_promo)

SUMMER (#litres_trial_promo)

Investors priced out by the bank — Alistair Osborne (#litres_trial_promo)

Election 2017 — Leading Article (#litres_trial_promo)

Saved by friends from across the water — Patrick Kidd (#litres_trial_promo)

US banned tower cladding — Alexi Mostrous, David Brown, Sean O’Neill, John Simpson, Sam Joiner (#litres_trial_promo)

Helmut Kohl — Obituary (#litres_trial_promo)

Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill: how civil servants lived in fear of the terrible twins at No 10 — Oliver Wright, Francis Elliott, Bruno Waterfield (#litres_trial_promo)

Food and service in a time machine — Giles Coren reviews Assaggi (#litres_trial_promo)

Sovereign wealth — Leading Article (#litres_trial_promo)

The primitive lost society of love island — Ben Macintyre (#litres_trial_promo)

Small acts of kindness that can save a life — Libby Purves (#litres_trial_promo)

People thought I was mad to offer my spare room to a homeless stranger — Alexandra Frean (#litres_trial_promo)

Pocket money, phone, rambo knife — Rachel Sylvester (#litres_trial_promo)

The Dunkirk myth never told our real story — David Aaronovitch (#litres_trial_promo)

My career’s in reverse and I couldn’t be happier — Emma Duncan (#litres_trial_promo)

Puppy love — Caitlin Moran (#litres_trial_promo)

The conservatives are criminally incompetent — Matthew Parris (#litres_trial_promo)

Justin Gatlin reminds us that sport is not a fairytale — Matt Dickinson (#litres_trial_promo)

Starting nuclear war is president’s decision alone — Rhys Blakely (#litres_trial_promo)

‘We’ll never be able to stop the hunger for revenge here’ — Anthony Loyd (#litres_trial_promo)

Photo Section (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_4b849226-bfb9-5972-aa41-e07303637a40)

Like its predecessor this volume brings together outstanding writing, photography and graphics from a year in the life of the world’s most famous newspaper. It covers an eventful, unsettled 12 months, from September 2016 to August 2017. In a new-year editorial on December 30, 2016 (reprinted here on p125), The Times took stock. If 2016 had been a year of “shocks, setbacks and slaughter”, the paper thought it would also seem with hindsight “a year of revolution … part of a rolling transformation of political institutions, and of geopolitical shifts”. Britain’s EU referendum and the election of Donald Trump had been manifestations of a populist rejection of established elites. They expressed the deep-rooted grievance of millions of voters who felt ill-served by representative democracy and to whom the rapid expansion of global trade had not brought prosperity.

The Times viewed the year ahead with trepidation, predicting that “the many cracks opened up in 2016 will widen in 2017”. To a degree they have. Britain, split almost down the middle by the referendum vote, is no less divided over Brexit than it was a year ago. Trump’s America is riven by dangerous tensions. Yet in some ways, this anthology suggests, the 2016 revolution may have stalled. Britain is no nearer knowing how Brexit might work or what it will mean, and a general election called to bring clarity had the opposite effect. President Trump’s efforts to turn rhetoric into policy have so far largely been frustrated. In France the presidential victory of Emmanuel Macron was no doubt a shock to the country’s political system, but the sudden rise of a wealthy, centrist, business-friendly financier hardly feels like a triumph of populism over the establishment. Meanwhile, around the world, elites cling stubbornly to power by whatever means they can.

It’s a gloomy picture, perhaps, but it shouldn’t – and doesn’t – make for gloomy newspapers. In a world of conflict and upheaval readers want accurate, balanced, immediate first-hand reports. They want powerful human stories that bring developments alive, reliable facts on which to base their own judgments, authoritative commentary and analysis to put the news in context and explain why it matters. Times readers expect their paper to take them seriously. They need to know the worst, and to understand it. But they expect also to be entertained, by articles on fashion or football or gardens or dogs that are as lively and as expert as the coverage of politics and world affairs.

An edition of The Times contains between 150,000 and 270,000 words. It never seems enough. Every night, as deadlines loom, good stories are cut back, held over or dropped altogether when something more urgent or important comes along. There are 110,000 words in this book. To claim such a tiny fraction of the paper’s annual output as “the best of” would be absurd. The hope is that the articles included nonetheless give an engaging picture of a momentous year, and show the quality and range of the journalism that The Times produces day after day.

Ian Brunskill

Assistant Editor

The Times

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (#ulink_54bf2a80-8d63-5429-9c8a-3b488d8789c5)

Special thanks to Matthew Lyons (production editor), Nasim Asl, Jack Dyson, Josie Eve and Ailsa McNeil (editorial assistants), Sarah Willcox (sub-editor), Mark Grayson and Andrew Keys (designers); and to Gerry Breslin, Jethro Lennox, Karen Midgley, Kevin Robbins and Sarah Woods at HarperCollins. Thanks also to the contributors and to the following Times colleagues: Grace Bradberry, Peter Brookes, Becky Callanan, Jessica Carsen, Magnus Cohen, Nigel Farndale, Hannah Fletcher, Richard Fletcher, Rana Greig, Fiona Gorman, Jeremy Griffin, Tim Hallissey, Robert Hands, Suzy Jagger, Nicola Jeal, Alan Kay, Alex Kay-Jelski, Jane Knight, Robbie Millen, Simon Pearson, Monique Rivelland, Fay Schlesinger, Tim Shearring, Mike Smith, Sam Stewart, Matt Swift and the Times graphics team, Craig Tregurtha, Emma Tucker, Pauline Watson, Giles Whittell, Rose Wild, Danny Wilkins, Fiona Wilson and John Witherow.

AUTUMN (#ulink_b98de636-f505-5a43-a30b-173657dfa961)

MERITOCRACY IS THE LAST THING BRITAIN NEEDS (#ulink_4c5c5ef1-1c70-551f-9026-56fb5aaf5041)

Philip Collins (#ulink_4c5c5ef1-1c70-551f-9026-56fb5aaf5041)

SEPTEMBER 16 2016

“IT IS NOT ENOUGH to succeed. Others must fail.” Gore Vidal’s waspish hopes for his friends captures, in an epigram, why Theresa May does not really mean what she says about meritocracy. Meritocracy does not mean meritocracy. At the beginning of their time in office every prime minister has to make the meritocracy speech. The ardour always fades because, looked at straight on, meritocracy is a radical and terrifying idea.

The term itself was designed as a warning rather than an aspiration. Michael Young wrote The Rise Of The Meritocracy in 1958 to raise the alarm that a society based on a narrow definition of merit, embodied in an intelligence test at an early age, is a terrible place to live. Young’s meritocracy descends into disorder as the sheep and the goats start to fight. There is nothing wrong, of course, with a weaker version of meritocracy in which talent and effort are rewarded to a greater extent than their opposites. This is what every prime minister is initially getting at, translated into the bloodless jargon of social mobility. But even that they cannot really mean.

This is why we have been treated to yet another turn of the wheel for the over-sold hysteria about grammar schools. When Gordon Brown took over from Tony Blair one of his first acts was to reform the royal prerogative powers, such as the declaration of war, that are carried out by the prime minister. Theresa May’s exhuming of grammar schools prompted the same thought I had then: is that all you’ve got? If a few grammar schools is all you’re about, then you’re not really about much. This will not be the full return of the binary distinction between grammars and secondary moderns. The school system is too diverse for that.

Besides, Mrs May’s advisers know all the objections to grammar schools. They know the cause of social mobility in the 1960s was the conversion of Britain, between the end of the First World War and the end of that decade, from an essentially blue-collar economy into a mostly white-collar one. Suddenly there was more room at the top. Grammar schools coincided with this change but did not cause it. At the height of their popularity, of the grammar school children who gained two A levels, less than 1 per cent came from the skilled working class.

This is a point so well established that it enabled even Jeremy Corbyn to get the better of Mrs May at PMQs this week. After the beating, Mrs May’s spokesman was unable to cite any evidence in support of her policy. That’s because there isn’t any.

That has not prevented plenty of Tory MPs and columnists from elevating their autobiographies to the status of policy writ. There really is no more firmly established body of evidence in all of education. So why does it have to be said over and over? Are these Tories so arrogant that they are impervious to evidence? No, they just don’t know what they are talking about. They are simply observing that there were more people mobile in their generation and ascribing that fact, wrongly, to schools.

The government’s green paper actually admits its own problem: “Under the current model of grammar schools … there is … evidence that children who attend non-selective schools in selective areas may not fare as well academically — both compared to local selective schools and comprehensives in non-selective areas.” The rest of the document is then an attempt to salvage selection from the jaws of this yawning disaster. The upshot will be that the conditions imposed on schools before they can opt to select will be so severe by the time the bill limps through parliament that there will be little incentive to do so. Most of the large academy chains have no need of selection. Mrs May’s speech on meritocracy was a grand vision saddled to a sorry policy.

The fabled popular demand will dissipate too. Grammars were not abolished by Tony Crosland in a fit of socialist envy. They were closed by Margaret Thatcher because of middle-class parents complaining to local authorities that their children were not getting in. Young put the politics of grammar schools perfectly: “Every selection of one is a rejection of many.” Meritocracy has the unfortunate effect of making aspiration a zero-sum game. My very stupid children (well, not mine, yours), with all their good fortune, will have to fall down a snake while your bright poor child climbs a ladder. No ordinary middle-class parent is going to stand idly by while that happens. It therefore follows that the policy meritocrat will have to commit to some policies even more unpalatable than grammar schools.

There is in fact a Meritocracy Party in Britain, which demands that the Queen abdicate and that only those with relevant experience, which would presumably include the Queen (Tory), be permitted to vote. They want inheritance tax at 100 per cent. I may have earned the money but my children have not and if advantage can be purchased, which it can, then the transfer from me to them impairs the principle of merit.

Advantage goes back a long way. In 1693 John Locke wrote a parenting guide, Some Thoughts Concerning Education. The best recommendation was that children should eat no vegetables but the rest has worn well. Locke points out that good citizens are created by good parents and it’s still true. Educated parents are marrying their own kind and talking to their children. High-income parents talk with their school-aged children for three hours more per week than low-income parents. By the age of three a poor child would have heard 30 million fewer words at home than one from a professional family.

It matters. How children perform in tests when they are three and a half is a strong predictor of how well they do at school years later. The best way to predict a person’s social position at the age of 19 is attainment at 16, which in turn is best foretold by attainment at 11. And you can tell who is going to do well at 11 simply by looking up who did well at seven. A meritocracy would therefore withdraw resources from the later years of life and spend earlier in the life cycle. The only government member I recall taking this seriously is a little-remembered person by the name of Andrea Leadsom.

The regime in Young’s Rise Of The Meritocracy collapses when the government takes the children of the poor into care to ensure equality of opportunity. Every politician wants the soft version of meritocracy in which the poor do well but nobody suffers. It’s a fantasy and that is why the pertinent response to Mrs May is not hysteria about a return to the 1950s but simply this: is that all you’ve got?

JEREMY PAXMAN: ‘I’M NOT ASHAMED TO SAY I’VE SUFFERED DEPRESSION’ (#ulink_f4fb0ae8-6d4e-5dc2-a43b-82b01dcb79bb)

Interview by Janice Turner (#ulink_f4fb0ae8-6d4e-5dc2-a43b-82b01dcb79bb)

SEPTEMBER 24 2016

JEREMY PAXMAN relished “war-gaming” interviews, a former Newsnight producer tells me: debating the research, plotting manoeuvres, setting bear traps into which ministers would tumble. So how do you war-game a man who knows all the moves? After his famous question about whether he prayed with George W Bush, Tony Blair cavilled at his intrusiveness and Paxo threw up his hands in faux innocence: “But prime minister, I’m just trying to work out what kind of chap you are.”

What kind of a chap is Paxman, beneath the suits, the elaborate disdain, the position in our culture — vacant since he left Newsnight two years ago — as the scary tutor/imposing father who sees through our dissembling and flaws? His memoir, A Life in Questions, abounds with great hack yarns about Diana, Princess of Wales, and the Dalai Lama, war reporting, political scuffles and BBC crises, yet personal detail is sketchy. He has declared his three children and partner, Elizabeth Clough, absolutely out of bounds. Indeed, no girlfriend gets more than a single line. While Paxo the man — what he feels, whom he loves — emerges rarely and fleetingly from his carapace of high snark.

So in 300-plus pages we glean that he sits on the toilet shooting squirrels out of the bathroom window, he’s happiest fishing and (thanks to an anecdote about Orthodox Jews) that he is uncircumcised. Yet those who know him well speak of a complicated man roiling with self-doubt who “struggles with existence”. Ask about his father, they say, whose approval he sought in vain. Ask about his depression. Ask Paxman if he is happy.

We meet at Galvin La Chapelle in east London and I have bagged us a table alone on the mezzanine high above the shiny City lunch crowd. Paxman is late, caught in cross-town traffic from his Notting Hill flat where he lives three days a week rather than commute from his family home near Henley, Oxfordshire. I watch him walk very slowly up the stairs. He wore out his knee running, is considering replacement surgery and is clearly in pain. (Later, when I see him wincing and offer to carry his suit bag, he splutters and tells me to f *** off.) Otherwise he looks splendid for 66: lean apart from a slight bay-window belly; thick, almost white hair; fine skin with that rich man’s holiday burnish. His azure linen jacket with elaborate stitching is very natty.

Old age, however, seems much on his mind and appears to revolt him. His most recent headlines were for blasting the magazine Mature Times for its stairlift ads and portrayal of people his age as “on the verge of incontinence, idiocy and peevish valetudinarianism”. (He has a rather Alan Partridge-esque vocabulary, calling party conferences the “gallimaufry of our democracy”.) I note that his memoir is rather ageist: he refers to “whiffy old wrinklies” and tells an unkind story about John Gielgud needing help to go to the loo. He writes that old people who don’t pay “direct” taxes (ie aren’t working) shouldn’t be allowed to vote.

Does he use his free bus pass? The eyebrows shoot up.

“I don’t have one.”

Why not?

“Because I’m still earning and I’m very happy if people want to give you a discount because you’re over a certain age. But I’ve just done four weeks filming a series about rivers. The week after next I’m in Washington. Why should I expect others to pay my Tube fare?”

Why do you believe you should be allowed to vote but people who’ve retired from jobs you can’t do in old age — roofers, say — should not?

“I did not say that!”

You said no representation without taxation.

“Yes. And there will come a point of course when no one asks me to do anything. It happens to all of us.”

So in the meantime you should be allowed to vote but they shouldn’t?

“Sometimes, life is like that, Janice. Unfair.”

For the first 20 minutes, after Paxo has ordered “heritage tomato” salad (scorn about what “heritage” means), mutton (scorn about how much “lamb” is really mutton) and a glass of white wine (which he believes doesn’t count as real booze), the interview comprises me asking a question and him knocking it down. It feels like a bizarre stress dream in which I’m on Newsnight playing Jeremy Paxman while the real Jeremy Paxman harrumphs and sneers. He calls me (humorously, maybe …) “a silly woman”, accuses me of misquoting him, tells me to “cast a more artful fly” and, as if abrading dim University Challenge contestants, cries, “Oh, come on!”

How the hell, I think, am I going to ask about his father? In the book, Keith Paxman is a puzzle, a shape-shifter, a domineering presence but also an invisible man, whom his son has clearly spent his whole life trying to fathom. Jeremy, his eldest child, was born near Leeds while Keith, a naval officer, was away at sea, and screamed when introduced to him. “Relations between us never really improved much.” His father had a vile temper and beat him for any perceived insubordination with sticks, shoes, cricket stumps or his bare hand. “Did I love my father?” he writes. “My feelings ranged from resentment to passionate hatred.”

Paxman is scathing about his father’s social pretensions and evolving accent as he leaves the navy and tries, falteringly, to rise in the world. Keith resents his wife’s family wealth, which pays for Jeremy, his two brothers and little sister to attend private schools. He becomes a typewriter salesman then ascends to manage factories across the Midlands. The family home grows to a country house and Keith adopts brass-buttoned blazers, a monocle and plus-fours. Paxman sees him as a try-hard and a phoney who once introduced his son to his golf-club friends as “one of those homosexual communists from the BBC”.

Moreover, the family’s social standing is precarious: middle class “by our fingernails”. Jeremy never feels at ease at Malvern College “with the boys who genuinely belong to the professional classes”, and a sense of not truly belonging and a bad case of impostor syndrome have never left him.

Later, when Labour nationalises the steel industry, his father quits and is transformed into a comedy huckster, buying cosmetics from a company called Holiday Magic in a pyramid scheme, then a chain of laundrettes. Finally, Keith reappears at the end of the book, as a coda, having moved to Australia and broken contact with his family. Paxman goes over to find him but the encounter is so vaguely explained, we don’t learn if his mother had been divorced or had died. It is as if Paxman, having started to exhume this painful matter, finds it too difficult to finish.

I ask what lasting effect his father had on his life. “There comes a point, about the age of 40, when you have to stop saying how you are is a consequence of how you were brought up. And particularly when you are 66, it is pathetic to say, ‘I am as I am because of things that happened in my childhood.’

“I understand what you’re digging for. I’m just …” I’m not digging — I’m asking about your memoir. “Yes, you are digging.” It’s my job to dig. “Well, you just said, ‘I’m not digging.’ Make up your mind.”

Wouldn’t you ask, in my position?

“Well, I might.” Eventually, Paxman says quietly, “I will not be portrayed as a ‘poor little me’ figure.”

The “homosexual communist” remark, he says, was “an example of wardroom humour”. But it stuck with you? “Oh, I remember it vividly, where it happened.”

Did your father ever say he was proud of you? “I expect so …”

Did you feel he was proud?

“It wasn’t a terribly … It wasn’t that sort of close, intimate relationship. But I do understand that if I answer your question saying, ‘Oh, I never felt he was proud of me,’ I know how you will write that. I’m like the boy in the jam factory who didn’t eat jam because he knew what went into it.”

When his father left, Paxman was about 24, a BBC trainee. He does not report whether his departure was expected or sudden. “I don’t recall. I wasn’t at home.”

Didn’t you all wonder over time why he didn’t come back? “No.”

He sees his siblings from time to time — his brother Giles was British ambassador to Spain — but they aren’t terribly close. “If we don’t see people very often … Intimacy is the consequence of familiarity, isn’t it?” He assumes his parents divorced, because his father eventually remarried in New Zealand and his stepmother brought Keith’s ashes to scatter in England. When I wonder how his father’s example influenced his own parenting he is instantly angry, accusing me of asking about his children. Which I wouldn’t dare. Then he says, “I think everyone is scared to some extent of becoming their parents and I suppose that would have been the case. The family relationships, I find they don’t resonate happily to me.”

Paxman’s mother, however, barely features in the book, except as quietly running the household. He doesn’t even note when she died.

“Both my parents are dead,” he says, taking off his glasses and rubbing his eyes. “It’s strange, death, isn’t it? However old you are, when you’ve finally lost both parents, there is a feeling of being orphaned. And I think it’s very cruel that all the very vibrant memories I have of my mother are now intertwined with the memory of how she looked at the point of death.” Was he there? “Yes, the skin kind of collapses on to the skull and you recognise the person, but you don’t recognise them. They’ve clearly passed from one state of being to another … I remember when she was young and she had this luxurious black hair which she kept pinned back in a bun. And she had three boys within three and half years or something. And boys are quite difficult …”

I ask how old his mother was when she died.

“I’m ashamed to say I cannot tell you.”

After his father had been gone for more than a decade, sending only curt Christmas cards, Paxman went to Australia to find him.

“I was astonished by his lack of curiosity. I mean, there were grandchildren he’d never seen, spouses he’d never met. It seemed as if we were part of a life he’d put behind him.”

Was it the journalist in him who wanted to go, or the questing son?

“Both of those things, I think. I wanted to see if he was all right and I was slightly concerned in case I was becoming him.” It is the most revealing thing he’s said in an hour. And I recall a childhood incident he describes of his sister finding their father sobbing on the bathroom floor. “I didn’t want to feel I was living my life as he lived his life … I think he was actually a vulnerable man and he probably thought cutting himself off was the only way to survive.”

Paxman refers to his depression (“I spent several years seeing a therapist, and several more on antidepressants,” he says in his foreword) in several brief incidents. When he was studying at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, friends recall him standing on a bridge saying, “It is completely and utterly meaningless, isn’t it?” then going to the pub. Aged 35, after stints in Belfast during the Troubles and as a war reporter in Zimbabwe and Lebanon, and having lost three good friends, he suffered insomnia and nightmares: “I didn’t exactly have a breakdown. But it was pretty like one.”

He has refused to talk about it before. “I don’t see any reason to be ashamed of saying I’ve suffered depression, as have a vast number of people. What I’m really not willing to do is try to appear as a victim.” As when discussing his father, Paxman’s greatest fear is of appearing to whine or look pitiful and weak.

Has he learnt anything during his years of treatment he’d care to pass on?

“The great thing is that unless we are all finished, the sun’s going to come up tomorrow. It’s always worst in the middle of the night, and what seems insurmountable at 3am, at 8am looks completely different. The critical thing they teach you doing CBT [cognitive behavioural therapy] is there is another way of looking at things. I would really like to learn that skill.”

Did CBT help him?

“I don’t think I was conscientious enough. But that is the key question: when everything seems black and shrouded in gloom and there seems no way out, is there another way of looking at it? Though,” he adds quietly, “if you’re in the grip of really serious depression, that’s almost impossible.”

Before I meet Paxman, I call several senior Newsnight colleagues who say many warm things. He is not a sulking prima donna: although intolerant of mediocrity, he would voice his view, then get on with the job. Nor is he a bully who “punches down”; he was patient with junior staff and, says one female executive, “was more receptive to women’s voices in the newsroom than most men in the Nineties”. But it is his complexity that instils loyalty. “Why he is a great broadcaster, not just a good one, is because beneath that outer shell of suave sophistication, there is an inner vulnerability.” This, points out another former colleague, explains his sensitivity when interviewing Terry Pratchett about facing death or the MP John Woodcock about his own mental illness.

In his memoir, Paxman expresses regret about his crueller questions to Gordon Brown (“Why does no one like you?”) and asking Charles Kennedy, “Why does everyone say of you, ‘I hope he’s sober’?” He believes his famous monstering of hapless junior treasury minister Chloe Smith was needed to bring the government to account, but asking, “Are you incompetent?” was “unanswerable and unkind”.

The media, he says, can only accommodate one idea of a person. “I know that I will always be Mr Rude or whatever,” he says. “But I know that’s not me. It’s a small part of any human being.” Yet that impenetrable outer shell, his air of not caring what anyone thought of him, created jeopardy. When you switched on Newsnight and saw Paxman was presenting, nothing seemed unsayable. And his jaded, nihilistic belief that fame, TV, politics, indeed much of human activity, is basically meaningless can be a useful mindset when dealing with the powerful. “The most striking thing about some of them,” he writes of establishment luminaries, “is how unimpressive they all are.”

The problem with Paxman is this default position — “You’re all lying fools” — solidified into a shtick. He quotes Alan Bennett on irony, the English amniotic fluid “washing away guilt and purpose and responsibility. Joking but not joking. Caring but not caring. Serious but not serious.” It encapsulates his father’s cruel wardroom humour, his own supercilious sneer.

At times he sounds high-handed, especially when discussing peers. Newsreaders, Jon Snow aside, are failed actors, not proper journalists. Nicholas Witchell is a “rather buttoned-up reporter who had written a book about the Loch Ness monster”. He says producers cried of one excitable broadcaster, “Stick a fresh battery in the news bunny.” (Is this Huw Edwards? “I have no comment to make.”)

Although he doesn’t dignify his existence with a mention in the book, he was reportedly most unpleasant to Jeremy Vine, whom he saw as a threatening younger version of himself. In Vine’s memoirs, he recalls that if he left a mug or family photo in the newsroom they were removed secretly by Paxman. “Jeremy Vine has written his memoirs?” he spits out with disdain. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” But you called him your “mini-me” and “the sorcerer’s apprentice” on air. Paxman huffs. “Did I? Good.”

What interests him now more than the TV ephemera of catching out politicians are the bigger questions. “Is there a purpose?” he says. “What do things mean? What is the right way to live? I would rather spend an evening talking about those than how to manage Vladimir Putin or reform the NHS. My great discovery in the past year or so is that news doesn’t really matter.” He doesn’t watch Newsnight — “It stops me having to tell people what I think of it.”

Since he left the programme he’s kept busy writing this memoir, a column for the Financial Times and making several TV series. Work, he finds, keeps the black dog at bay. Yet one question nags him: has he fulfilled his potential? “We all ought to ask ourselves that as we approach the finishing line. Could I have done something else? I haven’t got any great talents. Well, perhaps I could have put them to better purpose.”

Does this come from his father’s view that making things was more worthwhile than just reporting on them? “I think that’s a fair observation, and that is what I feel.”

The Conservative Party made a tentative approach about him being candidate for London mayor. But he says he’d make terrible lobby fodder. He sees himself as a maverick — “I’ve never been part of the establishment,” he insists — which seems at odds with his membership of the Garrick Club. He tells me, off the record, how it came to pass that, after initially being blackballed, he was allowed to join. But he is not naturally clubbable anyway, likes being alone or in his coterie of wealthy fishing mates including Robert Harris and Max Hastings.

We’re already late for the photoshoot and I’m pink in the face from the exertion of interview combat. At the end of a TV interrogation, Paxman always asked his subjects, “Happy enough?” Almost always they said yes. So I ask him.

“I’m going to say no,” he cries. “I shall say, ‘This is a disgrace!’”

But are you ever happy enough?

“I remember at school,” he recalls, “three of us talking about what to do. One chap wanted to be a doctor. I didn’t know what I wanted to be. The third fellow said, ‘I don’t mind what I do, as long as I’m happy,’ and I remember saying, ‘What a ridiculously superficial ambition,’ and he just looked slightly gobsmacked.” Then, a few years ago, Paxman heard the man worked for the United Nations and wrote saying their conversation had haunted him all his life: “I want to apologise because you were right and I was wrong.” The man responded, “Very nice of you to write, but I’ve no recollection of this at all.”

His friends have called him an Eeyore: “It’s always damp in my part of the forest,” he says. “But who wants to be Tigger? Who wants to be happy?”

So we head for the photographer’s studio where Paxman surveys clothes brought in by the stylist (“Look at these ridiculous trousers!”) then reappears in his own dark suit, barely worn since he left Newsnight. Seeing him there, back in his old armour, standing legs astride, braced for battle, with ministers to slay, I feel that old tingle of late-night jeopardy. And I miss that fearless, melancholy knight.

BATACLAN: ONE YEAR ON (#ulink_a86ed68f-1d2d-5fd0-aaef-55e778eb029b)

Adam Sage (#ulink_a86ed68f-1d2d-5fd0-aaef-55e778eb029b)

OCTOBER 1 2016

“I CAN REMEMBER thinking, ‘This is not the right day for my death.’”

Claude-Emmanuel Triomphe was lying in a pool of blood on the floor of Café Bonne Bière bar in Paris. It was just after 9.30pm on November 13, 2015, and the worst terror attack in modern French history was under way. Triomphe — a balding 57-year-old intellectual who has taught in Paris’s most prestigious university, worked in the upper echelons of the civil service and founded a think tank specialising in employment issues — had gone to Café Bonne Bière after a chance encounter with an American traveller.

They had just sat down and were about to order a drink when bullets ripped into the bar and into customers’ bodies from the pavement.

“I knew straightaway that I’d been hit. I realised it was serious. I lost an enormous amount of blood, the rescue services had not arrived, and I felt the strength leaving my body. I had time to think — and I can say this very calmly today — I had time to think about death.

“I thought, ‘I am going to die.’ I would not say I was panicking just then, but I was not in a good way and I was afraid.”

Later on, in hospital, Triomphe discovered that he had been hit by three bullets. One stopped 2mm short of his intestine, another cut through his sciatic nerve and a third went through his arm. He tells the tale now with alacrity, almost amusement, as we sit in another bar near his Parisian home.

At the time, the ambulance crew was unsure whether he would pull through.

“I realised they were afraid that I would faint and at one point I really felt a sort of great tiredness, like I would slip into sleep. I realised I had to fight against that, and I made enormous efforts to not slip into that sleep.”

Outside there was chaos. The three jihadists who had attacked Café Bonne Bière had sprayed five other bars and restaurants with bullets. Minutes earlier three more had detonated suicide vests outside the national football stadium in the capital’s suburbs. A further three were in the process of slaying concert-goers during a gig by the US rock group Eagles of Death Metal at the Bataclan venue.

The French equivalent of the 999 line faced an avalanche of calls — more than 6,000 to the police alone. Operators struggled to work out who had been shot and where. Ambulance crews wondered whether they would be targeted while tending to the wounded. Police squads were sent to one location, then diverted to another. And journalists — me included — tried to work out what on earth was going on.

The newsdesk asked me to go the Stade de France when the first bomb went off. I ordered a taxi, then discovered that there was a siege at the Bataclan and told the driver to go there. I never reached it. Paris was in lockdown and a line of police blocked me a couple of hundred metres away.

I sat on a bench and interviewed a man whose son had been shot in the foot in a restaurant farther to the east — or that is what he had been told by his son’s friend, who had phoned him. Like me, he was stuck behind police lines watching columns of armoured vehicles rumble towards the scene of the shootings. Like me, he had no idea what to do.

For want of a better idea, I took the Parisian version of a Boris bike to cycle through streets deserted by everyone except armed officers. The Rue de Rivoli was eerily empty, the Marais devoid of life. Bars and clubs had closed, and been ordered to lock their customers inside. I got into one — the only place I could find with an internet connection at 1am — and ended up writing my dispatch amid inebriated nightclubbers struggling to comprehend what had happened.

We discovered the next morning that 130 people had died and 414 were hospitalised.

Now, with the first anniversary of the shootings and bombings approaching, I am going back over the events of that night, and they still seem as absurd and macabre as ever.

The people I interviewed for this article — the injured, the bereaved, the emergency service representatives — share anger and pain but also perplexity at the sheer senselessness, the incredible stupidity of it all. The attacks — and those that followed in Nice, where 86 people died on Bastille Day, and in Normandy, where a priest was murdered in his church — have propelled France into a disturbing new era. There is distrust and fear, and a widening gulf between the white majority and the Muslim minority.

Yet among the survivors I met, there was little expression of hatred for the Kalashnikov-wielding thugs who perpetrated the Paris shootings — more a sense of withering disdain. “Cretins” was how the father of one victim described them. Triomphe said they were pawns in a sinister game that they did not understand.

Ten months earlier, 17 people had been killed in attacks on the satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo and on a Jewish kosher store in Paris.

Parisians knew another massacre was likely. Islamic State had called on its followers to target the French because of their involvement in the Syrian bombing campaign and their perceived hostility to Islam. The movement had more jihadists from France in its ranks than from any other European country and many had returned from the war zone. Nevertheless, the attack, when it came, caught Paris by surprise.

“We heard loud noises but we didn’t pay any attention. We just said to ourselves, ‘They’re Americans, they are putting on a show, they’ve got out some bangers.’”

Sophie is among 1,500 people who experienced at first hand the blind callousness of Islamist fanaticism when it struck at the Bataclan during a concert. She is a 32-year-old rock music fan who works in a baby-sitting agency, and we meet in her studio flat, which is decorated according to her distinctive tastes. There are several model Tardises that bear witness to her passion for Doctor Who.

On the back of the front door Sophie has stuck tickets from countless concerts and films she has seen. But there have been hardly any additions since last November. Sophie and Léa, her friend, had found a vantage point on a platform at the back of the Bataclan and the band was playing Kiss the Devil, one of its hits, when Foued Mohamed-Aggad, 23, Ismael Omar Mostefai, 29, and Samy Amimour, 28, burst into the venue.

First came the noise. Then the confusion and panic.

“All of a sudden, I had a big pain in my leg, it was like I’d been hit with a hammer, and that’s when I realised what was happening,” says Sophie. “I turned my head and saw three people with guns in their hands who were shouting at us, who were shouting that they were doing this for Syria and for Iraq.”

The majority of the 90 people who died in the Bataclan were killed in the first 7 minutes, when the terrorists sprayed the crowd with bullets. That, probably, is when Sophie was hit.

Then, for a quarter of an hour, Mohamed-Aggad, Mostefai and Amimour walked through the crowd cowering on the floor and executed people, apparently at random.

Sophie saw them approach. “They were three metres from me, and then I was really, really frightened because when they made eye contact with someone, they shot them.

“I had a T-shirt with skeletons and tattoos on my arms and I was afraid they would see me, so I quickly put on my jumper and thought if they don’t see me, if I don’t exist, I’ll survive.”

Earlier — before the killings — a young man had caught her when she stumbled. Now he had been shot and was lying beside her. “I saw his chest stop moving — he was right next to me — and with Léa, we put him on us to protect ourselves.” The terrorists went past without noticing them under the now lifeless body.

At about 10pm, two local police officers entered the venue and shot dead Amimour. Mohamed-Aggad and Mostefai fled upstairs, and silence descended upon the Bataclan. Sophie and Léa — and hundreds of other terrified rock fans — ran for the exit and carried on running until finally she sank to the ground by a door in Boulevard Voltaire.

“In fact, I was really hurting, but it was only when I saw the mass of flesh on my leg — it was absolutely horrible — that I realised I had been hit with a bullet. I smelt the smell of blood, and my shoe was full of blood,” says Sophie. Léa stopped a minicab and told the driver to head for the nearest hospital. Sophie had been hit twice, in the calf and the thigh, and was almost unconscious when she got there. She was bloodied, terrified, shocked — but alive.

At about the same time — 10.10pm — Chief Superintendent Christophe Molmy was entering the concert hall. Molmy, 47, is a tough cop — powerfully built, exuding understated authority and with a nose that looks like it has been flattened by a baseball bat. He heads the elite Parisian police Research and Intervention Brigade (BRI) and is accustomed to arresting hardened gangsters.

Shoot-outs are his bread and butter. He had been involved in one two days before November 13 when kidnappers had got jumpy during a ransom handover. He recounts the incident as you or I might recount the breakdown of a photocopier in the office. An ordinary problem in an ordinary day’s work. The Bataclan was different: haunting, traumatic, life-changing, even for him.

Molmy had created a rapid intervention unit after the Charlie Hebdo killings: 15 men who take their guns and stun grenades home at night so they can scramble within minutes. Now they were picking their way across a mass of bodies in a silence interrupted only by the sound of phones ringing as relatives sought news of their loved ones. Some were dead, some injured, some too frightened to move.

“We were destabilised because we had the wounded pulling at our trousers and asking us to help them while we were advancing. The members of the team all have medical training and tried to do what they could, applying tourniquets and talking to people, but you advance nevertheless. If you don’t do things with method they do not work out well.”

His unit had to make the venue safe for medics, rescue workers and forensic scientists. Molmy had no idea if the terrorists were still there. Perhaps they had fled with the 900 or so spectators who had left with Sophie and Léa. Perhaps they had booby-trapped the hall.

The team took 50 minutes or so to check the ground floor as survivors emerged from the toilets, the cupboards, the electrical cabinets, the suspended ceilings where they had been sheltering. Each one had to be checked in case they had explosives strapped to their bodies — a common Islamic State tactic in Syria. None did.

But of Mohamed-Aggad or Mostefai there was not a trace. “There was no noise, no shots, nothing,” says Molmy. “I said to myself that they had probably left, but we advanced prudently just in case.”

At about 11pm, the unit went upstairs. Still there was silence. Still they went on.

Suddenly a petrified voice shouted, “Stop. Don’t advance. They have taken us hostage.”

Molmy realised that Mohamed-Aggad and Mostefai had not fled. They were hiding in a corridor, and dozens of people were trapped with them: 15 to 20 behind the door, equal numbers in rooms off the corridor, and about 40 on the roof. Among them was a pregnant woman and a boy of 12.

Shouting through the door to the corridor, officers persuaded the terrorists to give them the number of one of the hostage’s phones so the brigade’s negotiator could call them.

The negotiator talked five times to them, at 11.27pm, 11.29pm, 11.48pm, 12.05am and 12.18am. “They were very nervous and tense and a bit incoherent,” says Molmy. “They were saying, ‘We want you to leave,’ but obviously we weren’t going to.

“They recited the jihadist diatribe, ‘It’s your fault — you’ve come to wage war in Syria so we are bringing the war to you.’”

The negotiator asked the jihadists to release the child. They refused. He asked them to release the women. They refused again.

The negotiator said he was getting nowhere — how could he with people determined to die and to kill? — and Molmy came to the conclusion that an assault was inevitable. The corridor was 1.35m wide and 8.5m long, it was full of hostages and at the far end were Mohamed-Aggad and Mostefai. “It didn’t look good to us. We thought there would be damage for us — dead and wounded — and deaths among the hostages.”

As soon as the officers entered the corridor, Mohammed-Aggad and Mostefai opened fire. Bullets flew everywhere: 27 hit the bulletproof shield on wheels (nicknamed the Ramses) behind which the officers were sheltering. Others hit the ceiling, the walls. A ricochet flew into the left hand of one of the officers.

Astonishingly, that was the only injury. For 90 seconds — an eternity, says Molmy — hostages were crawling under the shield or slipping beside it amid constant gunfire from the terrorists, and none was hit. “My colleagues at the front did an extraordinary job,” says Molmy. “They are heroes: they were being shot at all the time and they hardly responded. Throughout the intervention, from beginning to end, we fired a total of just 11 shots.”

When all the hostages had been pulled out of the corridor, Molmy’s team advanced on the terrorists behind the thud of stun grenades. But in the smoke-filled corridor, the two officers pushing the Ramses did not see the stairs at the end. The shield — 80kg of it — escaped their grasp and fell down the steps, and the terrorists sprang forward, guns pointed at the officers. The two men at the front of the police column reacted faster. Mohamed-Aggad and Mostefai were shot dead before they could pull the triggers on their Kalashnikovs.

It was 12.20am and the siege had ended.

An hour or so later Professor Philippe Juvin, head of the accident and emergency department at Georges Pompidou Hospital, learnt that the wounded were being evacuated. He was told to expect a large number of casualties.

Juvin had already asked the usual Friday night array of patients waiting in A&E — the drunks, the hypochondriacs, the footballers who had sprained their ankles — to go home unless they were critical. All but two did. He had summoned all available staff and put out a Twitter message asking for help from doctors or nurses in the vicinity.

Juvin, 52, is a slim, energetic doctor who speaks with a quietly reassuring certainty. He does not look like the sort to panic in a crisis and he is used to dealing with bullet wounds inflicted by combat rifles. Not only did he spend eight months with the French army in Afghanistan, but his A&E department regularly receives gangsters injured in gunfights.

The wounds are not pretty — “If a pistol bullet hits the foot it goes in and out,” he says. “With a Kalashnikov bullet, there is no foot left” — but at least they rarely get more than one victim at a time.

That night, his department treated 53 patients with Kalashnikov wounds. “The big difference is that the people we get with bullet wounds are usually the bad guys. We treat them because it’s our job but we don’t necessarily have much sympathy for them.

“On November 13, we were getting people like you and me, or like our children. We could identify with them. There was an emotional load.”

It was a frantic night. There were too many ambulances — 30 or so — for the A&E reception area. No one had imagined so many turning up at once. They created a traffic jam and Juvin had to go into the street to cast an eye over the casualties in the ambulances. Signs of an internal haemorrhage? He waved the ambulance on. A bullet in the arm? He told the patient to do the last 50m on a stretcher.

Juvin and his improvised team — the hospital’s doctors and nurses and those who had turned up to help — checked pulse, blood pressure, wounds. Who needed an immediate operation? Who could wait until the next day?

They flew down corridors, bandaged injuries, made rapid life-or-death decisions. Yet Juvin’s abiding memory of that night is of silence. “They had debilitating wounds that were probably very painful, and nobody spoke.

“Usually people tell you when it’s hurting. There, everyone was in a state of stupefaction. I went into a cubicle and there was a man with a badly damaged leg. I think he was in pain, but he was saying nothing. I said to the doctor treating him to give him morphine anyway.

“He was somewhere else and could not express his pain. When you have experienced something like that, you enter a dimension that no one can describe.”

By 6.30am A&E was empty, the patients all having been dispatched to operating theatres or to other departments. None had died in care during the night.

Juvin went home to sleep. He couldn’t. He came back to the hospital. There was a queue of people waiting to give blood and families turning up to ask whether their relatives had been hospitalised at Georges Pompidou. Among them was Georges Salines, a doctor who heads the Environmental and Health Office at the Paris council. He had gone to bed the previous evening unaware that Lola, his 28-year-old daughter, was at the Bataclan. He had not watched the television and had no idea that anything untoward was going on.

At midnight Lola’s brother called. He knew about her plans and knew what had happened at the concert hall. He had tried to call her. There had been no answer.

Salines, 59, a slender, fit-looking man with a welcoming smile and a precise discourse, telephoned the emergency helpline set up by the authorities after the attacks. He could not get through. He phoned again, and again, and again. The operator who responded at last — hours later — had no information about Lola and advised him to get in touch with the Paris hospitals. Hospital receptionists said they would phone back. None did.

Somebody told Salines that Georges Pompidou Hospital had patients whose identities had not been established. But when the family arrived, managers said that was untrue. The patients had been identified. Lola was not among them.

“It was only at the end of the afternoon that we discovered her death in very painful circumstances,” said Salines. A friend had telephoned the emergency helpline, which was functioning correctly by now, and the operator disclosed that Lola’s name was on the list of the dead.

Word got around. It appeared on the internet. There was a denial and confusion. Salines called the emergency number himself. The operator confirmed Lola’s death.

“My daughter died for nothing, for an illusion, for a folly. It’s absurd,” Salines said in L’Indicible de A à Z (The Unspeakable from A to Z), a book about his reaction to the attacks.

In it, he describes Lola, who worked in the children’s books department of a publisher, in these terms: “You liked books, films, drawing, travelling, rock music, children, Billy the Cat, lemon tart, Belgian beer, brunch at the Bouillon Belge bar, singing while playing the ukulele, roller derbies, your friends, your mum, your brothers, your boyfriend, your girlfriends, a kiss on the cheek, making love. You loved life. And all those who knew you liked you.”

The months have passed and the scars remain — physical or psychological — for those involved.

Sophie needed two operations, three general anaesthetics — the third to change her bandages — and 43 stitches. She has a bullet in her pelvis and fears that grip her day and night.

“When I go to sleep, I still see what happened almost every night. Either I see them or I hear them. There is the fear. For a long time it was very complicated to leave home. I still don’t take the métro or commuter trains. I only take the bus.

“Before, it was simple to make plans. Now I advance day by day. When I go to bed I wonder what will happen tomorrow and what will I see on the news.”

Christophe Molmy has been affected, too: “You don’t emerge unscathed from an intervention like the Bataclan. It’s impossible.”

He organised sessions with psychologists for his brigade and gave them and their families the opportunity to make appointments on a one-to-one basis. Some did; the majority did not. “We are still in a macho culture where we say, ‘Nah, I don’t need that,’ but in fact we need it,” he says. “I saw the psychologist.”

We meet in his office at the end of a warren of corridors in the 19th-century building that is the Parisian equivalent of Scotland Yard. He had never confronted terrorism before 2015. Now he lives permanently with the threat — a phone at his side at all times, in the shower, everywhere — and admits it has changed his job. “We always used to intervene against gangsters whom we tried not to kill. Today if we go in against terrorists, we go to kill the terrorists. We won’t manage to get them to put their hands up.

“We are becoming a little like paramilitaries. We are training and equipping ourselves like soldiers to fight a war.”

He talks about the old days of fighting criminals with a certain fondness. “We arrested them; they behaved well; we understood each other. We could have a bite to eat together. But what am I supposed to do with people who come to die? The human relationship is not the same. I don’t even know if there is a human relationship.”

Surprisingly, perhaps, Georges Salines seems almost the most sanguine of all, despite the loss of his daughter. When we meet in his office, he looks bright-eyed, and says in his book, “I am sad from time to time, I sometimes cry, but I sleep, I work, I talk and I sometimes laugh. You can’t avoid the suffering but resilience is possible, particularly in a family whose members love each other.”

Salines is head of 13 Novembre: Fraternité et Vérité, an association set up by victims two months after the attacks, and he has used the post to denounce the shambolic organisation faced by relatives of victims in the aftermath of the attack — some being shown the wrong body in the morgue. But he is not vindictive, and insists on the need to heal the split in French society, to avoid marginalising Muslims and pushing them into the arms of the terrorists.

He says in his book that he has no hatred for the jihadists. “I have never experienced this feeling,” he says. “I cannot hate the sinister cretins who took my daughter’s life and lost theirs in this business. They are victims, too.”

Antoine Leiris, a French radio journalist, has written a book, too, after losing a loved one — Hélène Muyal-Leiris, his 35-year-old wife — at the Bataclan. As with Salines, the book is more about love than hate: Vous N’Aurez Pas Ma Haine (You Will Not Have My Hatred) is the title.

Leiris recounts his love for his wife, and for Melvil, their 17-month-old son — and his fear, uncertainty and pain at the realisation that he will have to bring up Melvil on his own. Of the killers, he has little to say. “I don’t know who you are and I don’t want to know. You want me to be frightened; you want me to look at my fellow citizens with suspicion; you want me to sacrifice my liberty for security. I won’t.”

Claude-Emmanuel Triomphe, who had two operations and a month in hospital after being injured in Café Bonne Bière, says much the same thing. “I feel indifference for them. I feel no hatred. I tried to have hatred; I thought it’s not normal after all they did to me. If I must express a feeling it is rather pity — pity in the sense that these guys have massacred their own lives: ‘Not only have you massacred the life of other people but you have messed up yours as well.’”

He says he has no nightmares, no worries about going out. After months of lethargy he has rediscovered some of his old intellectual energy, too. Nothing is quite the same now, however.

Having given up his post as head of a think tank, he wants to specialise in the estates that are home to a generation of second-generation immigrants, among whom a handful have turned to radical Islamist violence.

“I need to understand why my country is affected by terrorism, why my country has manufactured more jihadists than any other in Europe. It’s not to say that other countries are not affected, but France is particularly so.”

The incomprehension is widespread in France, and it is Sophie, perhaps, who sums it up best. “You ask yourself questions: what was in their heads when they did that? The youngest terrorist at the Bataclan was 23. Me at 23, I was in Lyons, in university and thinking how I was going to dress the next day and not going to a concert hall to kill people. These are questions that remain and to which we will not have an answer.”

YOU CAN’T TRUST THE PEOPLE WITH DEMOCRACY (#ulink_05dac446-1732-5cd6-bccc-ee5d9bc00db0)

Roger Boyes (#ulink_05dac446-1732-5cd6-bccc-ee5d9bc00db0)

OCTOBER 5 2016

IT MUST HAVE seemed like a shoo-in for the Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos. After four years of negotiation with Farc guerrillas, a peace deal was unveiled to the accompaniment of a choir singing Beethoven’s Ode to Joy. After half a century of debilitating war, how could anyone vote against peace in the subsequent referendum? In the end, though, he set himself up. It was a bit like the US civil war general whose last words, glancing at the enemy lines, were: “They couldn’t hit an elephant from that dista …”

It wasn’t just the Colombian referendum that went awry. There is a quiet revolt under way across the globe. In vote after vote, people have been rejecting the guidance of political establishments, baffling elites and adding to the sum of anger in the world. In the age of rage, direct democracy is a risk. Referendums are infallible only for dictators — think of Napoleon, master of the strategic plebiscite — when instructions are handed down to voters, when ballot boxes are stuffed and there’s a secret police snitch living next door.

The fact is that in free societies a government should not abdicate its responsibility to govern by using a single-issue vote to demand guidance from ordinary punters. Clearly if you want to avert a populist avalanche you should keep capital punishment or mosque-building off the ballot paper. And by now leaders should have learnt too that referendums are not a suitable vehicle for deciding on war, peace or immigration. Viktor Orban, the Hungarian prime minister, has just asked his citizens the impossibly loaded question: “Do you agree that the European Union should have the power to impose the compulsory settlement of non-Hungarian citizens in Hungary without the consent of the National Assembly of Hungary?” Of those who voted, 98 per cent rejected the idea, as was intended. But most voters stayed at home, perhaps sensing that the vote wasn’t about migrant quotas at all (since they are more or less off the table anyway) but rather propelling Orban to a new level in his gladiatorial contest with Brussels. Many Hungarians are quite comfortable inside the EU.

The problem with referendums is that they become a receptacle for grievances and bear little relationship to the question posed. Take Mark Rutte, the Dutch prime minister, who earlier this year was saddled with a referendum on the ratification of an economic deal between the EU and Ukraine. The treaty had been agreed by the government, ratified by all other EU states and was 2,135 pages long. The Dutch rejected it, not because they had done their homework but because they were railing against weak government, against EU dogma and against the possibile eastward expansion of the union. Rutte was ambushed and called the No vote “disastrous”. Vladimir Putin rubbed his hands with glee and called it a truly democratic act.

The fact is that voting in a referendum can, without knowledge and preparation, become an almost random transaction between leaders and led. The political philosopher Jason Brennan calculates that the probability of your individual vote changing policy is about as low as winning the lottery. You could of course win hundreds of millions but it is still irrational to buy a ticket. And so it is with direct democracy. Voters, he says, “have no incentive to be well informed. They might as well indulge in their worst prejudices — democracy is the rule of the people but entices people to be their worst.”

Most democratic governments that deploy referendums do so out of weakness. In doing so they fool themselves that the wisdom of the people must inevitably support their world view. That’s how Juan Manuel Santos and David Cameron ended up in the same leaky canoe without a paddle. The Brexit referendum was a way of pacifying the Conservative Party. Cameron failed to grasp the potency of a national vote that fused mild dissatisfaction with the EU and the seeming inability of the government to get a grip on immigration or shield British jobs from a global slowdown.

By the end of this year there will have been eight major referendums — the next crucial one is Matteo Renzi’s attempt to secure backing for his constitutional reforms in Italy. It’s too late for the Italian premier to call it off now. If he loses in December, he could also lose office. If the Five Star movement and the Northern League take power in the resulting election they are promising a referendum on Italy’s membership of the euro. Few analysts would now rule out an Italian No vote. But whatever the verdict, the uncertainty of a referendum campaign would bring chaos to Italy, where the banks are already wobbly, and speed the unravelling of the eurozone.

The watchword has to be: listen to the people at your peril. Referendums can act as the safety valves of democracy but never as their engine. If legislators run away from their responsibility to consider and scrutinise complex questions, then power will seep away from the centre. The biggest risk posed by Donald Trump is surely that he could undermine or circumvent instititutions that keep America on an even keel. James Madison, the fourth American president, identified the problem: democracies endanger the right of minorities and must therefore devise solid institutions to protect those rights, civil liberties and free trade. Referendums, over-used and cynically steered, can end up subverting rather than enhancing democracy.

It is too late for the Colombian president and for David Cameron, but let’s declare a five-year moratorium on referendums. And yes, that means you too, Scotland.

BURNT AND TORTURED MIGRANTS FILLED DECKS AS WE RUSHED TO HELP (#ulink_ccd1b16e-062c-5a4d-a9f6-b1809155fa43)

Bel Trew (#ulink_ccd1b16e-062c-5a4d-a9f6-b1809155fa43)

OCTOBER 8 2016

Saturday, October 1

“Dignity is a dancer,” jokes Captain Louis Ferres when the floor lurches sideways as we drop off a 2.5m wave. The battered ship that can hold up to 450 people is one of three that Médecins Sans Frontières uses to patrol the Mediterranean, searching for migrants in distress. Everyone on board, including Carla the cook, works on the rescues. Dignity pirouettes her way to the search and rescue zone 20 nautical miles off the Libyan coast where most migrant boats run into trouble. Huge waves wash over the deck. Half the non-sailors aboard are in their bunks throwing up.

We are told we may not see a rescue as even the most ruthless smugglers don’t force migrants into the sea in bad weather. But we still spend the afternoon putting together 450 emergency care packages — socks, nutritional biscuits, water and a towel. There is a strict cleaning schedule to prevent disease spreading through the ship. On Saturday night it’s my turn to scrub the inner decks, which I manage without vomiting.

Sunday, October 2

We are woken by news that there will be a rescue at 9am. More than 100 migrants in a rubber dinghy called the Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre in Rome by satellite phone at dawn but it takes Dignity four hours to reach the position. By the time we arrive the dinghy is nowhere to be seen. Courtney, the ship’s nurse, begins to worry. They would have been at sea now for at least ten hours.

Likely weakened by months of starvation and ill-treatment in Libya, many don’t last a couple of hours exposed to the blistering heat of the sun. A co-ordinated effort with helicopters and nearby warships finds the dinghy. I jump aboard the rescue speedboat, which cuts through choppy waves to the dinghy. The terrified faces of women and children peer up from the bottom of the waterlogged tub, where they are crouched in lines as if on a slave ship.

This is the dangerous part. Desperate and delirious, people may try to jump aboard and risk turning the boat over. “Try to stay calm, we will rescue all of you,” urges MSF’s Nicholas over a megaphone while we hand out life jackets. The sickest — including an emaciated Ethiopian boy of 16 — are hauled aboard in the first round. When everyone is on deck and registered, people open up about the hell they escaped in Libya: floggings, rape and kidnappings for ransom. They are transferred to a Save the Children vessel returning to Italy.

Monday, October 3

The shriek of the rescue alarm wakes us. It’s 6.30am and a drifting boat has bumped the Dignity. The rescue goes well but the MSF team is told of a second, third and fourth boat in the area. The smugglers spotted a break in the storms and packed thousands into life rafts then scuttled home to make more quick profits before the winter ends the crossing season.

The stink of fuel knocks the breath out of me as the survivors of the second rescue stagger on board, their skin coming off in strips. The medics rush to treat a few who have stopped breathing. One pregnant woman grabs my arm and, pointing at a raw strip of flesh, screams. Another woman writhes on her back on the floor, screaming too. A third points to her shredded calf. Then it hits me: these are chemical burns from boat fuel.

“Get their clothes off and shower them now,” a voice shouts. We strip most of the 90 men, women and children and hose them down. I carry semi-conscious women to the showers. “We need to support a woman in the hospital to sit upright so she can breathe,” says Irene, grabbing me. I end up, covered in blood and faeces, cradling Lovett to keep her breathing.

I hold the hand of her pregnant sister, Joy, who dies on the bed beside us. Her body is packed in ice and placed in the bow. Lovett and the little boy are airlifted to hospital by the Italian coastguard, who won’t take Joy’s body.

Tuesday, October 4

The soft sobs of the Nigerian woman who lost her two boys, aged four and five, the day before are heard on deck. With nearly 420 migrants on board, including toddlers and a corpse, Dignity sails back to Italy. We are posted in shifts as guards to defuse any arguments, spot medical problems and regulate the endless queue for the toilet.

In French, Arabic and English, the men on deck, fleeing Ivory Coast, Mali, Nigeria and Sierra Leone, tell their stories. In the evening I check on the Nigerian girls from Monday’s horrific sinking. They giggle at photos of my stupid cat and tell me about their favourite sugar-cane recipes.

Peace, who is spattered with torture scars, asks: “Do white people in Europe like black people? I’m afraid. We’re always treated like animals.” At night, while on watch on the men’s deck upstairs, I listen to Michael, 17, from Nigeria, talking of “making [his] mother proud” in Italy. “Do you think they will let me study? I want to be a doctor.”

Wednesday, October 5

Overnight the Italian coastguard again refused to take Joy. Her corpse is beginning to smell. In the morning we dock and the ship goes quiet. Everyone is split into groups depending on their injuries and their ages. They go ashore for medical checkups and registration.

The UN says that more than 80 per cent of Nigerian girls landed in Italy are trafficked into prostitution. I warn the girls to keep together and stay in the reception centres. Hope is mortified that she has only a blanket to wear. I wash and dry my pyjamas to give to her.

Hours later, as I leave the boat, I hear my name called. The girls are still being processed. Hope, wearing my pyjamas, is grinning. We hug and they board buses, promising to stick together.

Thursday, October 6

More than 10,000 people were pulled from the water in 48 hours this week. We have no idea where people have gone or if Lovett and the others made it. I add as friends the few who have Facebook. Kougan, 23, from Cameroon, who kept me company on night watch, pops up on Messenger: “I very grateful to become your friend Bella, take care for ur self.”

‘TANTRUMS AND SHOCKING RACISM’ OF INQUIRY’S DYSFUNCTIONAL DAME (#ulink_7f8434c5-a52b-5d22-a2d9-a36f8ecdb80f)

Andrew Norfolk, Sean O’Neill (#ulink_7f8434c5-a52b-5d22-a2d9-a36f8ecdb80f)

OCTOBER 14 2016

ON A SUMMER afternoon this year Dame Lowell Goddard stood at the doorway of her Westminster office and shouted in anger. Unless she got her own way, she is said to have declared, “I’m going to pack my bags, go back to New Zealand and take this inquiry down with me.”

A visitor to the headquarters of the national child sex abuse inquiry might have been shocked, not least because the threat was made by the judge paid £500,000 a year to lead an investigation forecast to run for a decade at a cost of £100 million.

Dame Lowell’s staff, however, barely flinched. They were used to her tantrums, and worse. Multiple senior sources have told The Times that the judge peppered her 16 months at the helm of Britain’s biggest public inquiry with racist remarks and expletive-ridden outbursts. Insiders say that Dame Lowell, 67, also appeared to have memory lapses and failed to grasp legal concepts.

She allegedly said that Britain had so many paedophiles “because it has so many Asian men” — a comment that left colleagues stunned. “I was so shocked to see the number of ethnic people,” she is said to have told a colleague, while she allegedly commented that she had to travel 50 miles from London to see a white face. Her home in the capital was a smart, taxpayer-funded flat in Knightsbridge.

Several sources described Dame Lowell’s reluctance to question the propriety of the royal family. Discussing the Prince of Wales’s friendship with a bishop jailed last year for sex offences against young men, the judge is said to have insisted: “Prince Charles couldn’t possibly have had anything to do with that, not with his breeding.” The source added: “For someone who claimed not to understand what the establishment was, she had a reverence for it that was quite astonishing.”

On the 23rd floor of Millbank Tower, where the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) has its offices, staff soon realised that they had a problem. They were supposed to be putting in place the foundations of an investigation into suspected abuse at dozens of institutions, including schools, care homes, the church, the armed forces and parliament.

Since being launched by Theresa May in 2014, IICSA has hired more than 150 staff, opened three regional offices, started the Truth Project to allow abuse victims to give testimony anonymously, commissioned an academic study and begun a legal disclosure exercise demanding that institutions under investigation hand over millions of pages of documents.

Yet it was so dysfunctional under Dame Lowell’s leadership that work often ground to a halt because senior staff felt “totally paralysed”, one said.

Former colleagues, who have asked not to be named, were puzzled then increasingly troubled. One said that staff who were committed to the inquiry’s success felt trapped in “an impossible situation”. They felt they were led by someone who at times behaved “like a very angry child”.

“The pressure was immense. She was rude and abusive to junior staff, she didn’t understand the issues and, worse than that, she used appalling terms all the time. It was almost intolerable,” the insider claimed.