The Times Great Military Lives: Leadership and Courage – from Waterloo to the Falklands in Obituaries

Ian Brunskill

Michael Tillotson

William Hague

Guy Liardet

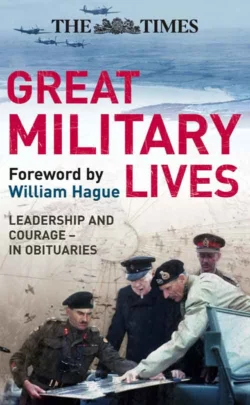

The Times for over 150 years has been providing the most respected and perceptive verdicts on the lives of outstanding individuals. The Times Great Military Lives is an authoritative and fascinating collection of obituaries depicting the great military commanders of the 19th and 20th centuries.The obituaries collected in this volume are of outstanding military commanders all of whom were remarkable men. Sometimes complex and difficult, often intellectually brilliant and physically brave, always with the confidence and clarity of mind to take the difficult decisions which might carry a vital battle or turn a campaign. Above all, they were great leaders of men, ready to bear the lonely responsibility of high command, ever aware that they had the lives of thousands - even the fate of nations - in their hands.The obituaries are reproduced here as they were printed at the time, with the contemporary assessment followed in each case by a current perspective by Major-General Michael Tillotson, military obituaries writer for The Times, who with Ian Brunskill, the paper's obituaries editor, has selected the subjects for inclusion.Great Military Lives tells stories of grand strategy, tactical boldness, and courage and ingenuity under fire. In depicting an age of almost ceaseless conflict, it bears witness to an enduring ideal of selfless service - on land, at sea and in the air - to which those fortunate enough to enjoy peace will always owe so much.Those commanders featured include:Wellington, Montgomery, Patton, Trenchard, MacArthur, Slim, Ulysses S Grant, Robert E Lee, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Sitting Bull, Count Helmuth Von Moltke, Macmahon, Cetywayo, Togo, Lord Roberts, Paul Von Hindenburg, Erich Von Ludendorff, Lord Fisher, Foch, Haig, Beatty, Scheer, Kemal Atäturk, Lord Allenby, Gustaf Mannerheim, Gerd Von Rundstedt, Heinz Guderian, Earl Wavell, Sir Mav Horton, Alanbrooke, Sir Claude Auchinleck, Cunningham, Karl Dönitz, Erwin Rommel, Eisenhower, Albrecht Kesselring, Nimitz, Erich Von Manstein, Rokossovsky, Zhukov, Lord Dowding, Sir Arthur Harris, Adolf Galland, Lord Slim, Orde Wingate, Matthew B Ridgway, Sergei Gorshkov, Sir Walter Walker, Fleet Lord Fieldhouse.

Great Military Lives

Foreword by

William Hague

THE TIMES

A CENTURY IN OBITUARIES

GENERAL EDITOR: IAN BRUNSKILL

EDITED BY GUY LIARDET AND MICHAEL TILLOTSON

TIMES BOOKS

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u45f7e8af-5397-5f7d-8642-9f2ae21002f1)

Title Page (#u7977549b-34e1-50ea-a6cb-f4cba83d2b7e)

FOREWORD WILLIAM HAGUE (#u4808d5e7-2cd1-5cfb-b371-a9f41da204fc)

INTRODUCTION Major-General Michael Tillotson (#ue42edf9a-2c7a-506a-a103-17b0d4666ecc)

WELLINGTON (#u0bf5fc3a-dda5-5fe4-b2a2-007f6d25d159)

RAGLAN (#ub3dc669c-8130-5041-8e65-1ba2465058cf)

GRANT (#u8bebf308-0c6c-5008-9586-47a95077cbd0)

LEE (#uebd6e22f-2034-52ff-838e-19ad9b6e6c04)

GARIBALDI (#ud228ac2a-cc05-5f58-9b7d-468f0c3ee338)

SITTING BULL (#ue1666ff0-2a13-5361-9640-97c1ddaeb755)

MOLTKE (#u21e0e53d-734c-57a8-b3d6-87493547391b)

MACMAHON (#u9239f421-133f-53df-882e-514e79b3b689)

CETYWAYO (#u4b35be1a-1628-5aab-8a2d-4f386b2cb64a)

TOGO (#u7e3872a3-d662-5704-ba39-f510e83458f4)

ROBERTS (#u789f23eb-0849-5825-90ea-3504d7433ab5)

HINDENBURG (#u6361d804-d12e-5dc2-8824-11db97529771)

LUDENDORFF (#u8f767529-4498-51e0-a5b1-4ed5940bcaec)

FISHER (#uaf0a9445-7fb0-5bcb-ba05-7f3199eeaabd)

FOCH (#u29e55986-5b1d-56b5-8eaf-6bdc168c6c2a)

HAIG (#ueb0f7327-1aad-5e65-9ba8-9f5c07344303)

JELLICOE (#ubd3d677d-36c0-5482-af2e-b931ad69fb73)

BEATTY (#ub9fd9c34-acbd-5947-aa57-f5b3f2f47347)

SCHEER (#u58d65c43-502a-55be-bcf4-e7282ad099da)

ATATÜRK (#u51b32668-babd-5a34-a275-29c5c5d1ad66)

ALLENBY (#u05b329b7-d313-5524-8fc8-d4412a4fcce5)

TRENCHARD (#u347d318b-3a78-57bf-bddd-4c289e31c098)

MANNERHEIM (#u08543a78-5d05-577c-bdc6-14af2ce1d523)

RUNDSTEDT (#u23c5afa2-3817-5638-af7d-458ebc7e5eb9)

GUDERIAN (#u290e2e86-21e0-5a3b-97f1-be6c320c9b86)

WAVELL (#u7fbc53ef-a51e-501c-b0be-38ec17ab6297)

ALANBROOKE (#uf90cf636-7024-520e-9b61-8363fc9cb665)

AUCHINLECK (#u9562d16a-68de-5edf-a043-5cde33e1d135)

CUNNINGHAM (#ufb5fb28c-a498-5409-ac3f-a96c3cfa0789)

HORTON (#ufa85fc7d-fed8-5a96-bcba-49adfc6d6385)

DÖNITZ (#u3c59e6ed-8414-5b97-b210-24ddc3de5b3d)

ROMMEL (#u2d7ba3fd-3f10-5e71-879c-977a92e553e0)

MONTGOMERY (#ua2ef2d40-e6f2-58a2-95ab-11b15d07b9b4)

EISENHOWER (#u976174b2-7063-5136-bd0b-41bbe0ddb85f)

PATTON (#u734d09ac-0d6c-5638-a36f-eabfb788817f)

KESSELRING (#u0e62d512-d158-5fa9-a6ae-50f910f4becb)

MACARTHUR (#uec5b16af-72be-5ec6-97e8-4a0166ced8bc)

NIMITZ (#u57e526b3-a343-5e70-b571-2d7334b1ffed)

MANSTEIN (#ue985283f-1c71-5d3b-a588-7da4d4b0e2cb)

ROKOSSOVSKY (#ua574f4f1-5886-5b43-ad72-68f10eeb0eea)

ZHUKOV (#u39817f20-c4d1-5019-91f3-c279f25862f5)

DOWDING (#ucadbf8f6-609a-561c-bc23-8ae5c5085203)

GALLAND (#u3db70e1e-3ccf-5904-8a01-0cfeb22003f6)

HARRIS (#u29b35b23-9088-543d-9a29-53fe50636871)

SLIM (#u8e4383e7-1b0f-5909-8e87-3084dfd24df8)

WINGATE (#u43ac803f-35c4-5f97-963c-78ff2b09b526)

RIDGWAY (#u7591c4a9-44af-52d8-aa42-4ee8d5ca7c8b)

GORSHKOV (#u8b9a347e-6e87-5a75-8d7d-86d085f6087c)

WALKER (#u13a41211-d1d5-5833-9eae-e5875ac15c1b)

FIELDHOUSE (#u04da1033-909c-5c8f-81ec-eeb2ec51bf95)

Copyright (#u22458270-da3c-59f9-9b16-e1fd51c2caf2)

About the Publisher (#u5d058310-4c36-5e3c-8aa1-776a6d070007)

FOREWORD WILLIAM HAGUE (#ulink_19aaa15b-ccd9-5735-8ae6-4d825eadcf4e)

Politicians should always be very careful when commenting on military matters. My own hero, William Pitt the Younger, was right to say that ‘I distrust extremely any ideas of my own on military subjects’, despite the fact that he was the longest serving war leader in the modern history of Britain. Even he, a statesman who built the great international coalitions against revolutionary France, found that as a man who had never seen a battlefield, his second-guessing of generals from Downing Street could lead to disaster.

This magnificent collection of obituaries of great military leaders from The Times offers plenty of reminders of just how tense the relations between generals and political leaders can be in wartime: Lord Alanbrooke, one of Britain’s best Second World War Generals, is quoted as saying of Winston Churchill, ‘He is quite the most difficult man to work with that I have ever struck, but I would not have missed the chance of working with him for anything on earth’.

Yet some of these impressive men of war went on to become the political leaders of their nations, from the Duke of Wellington and Ulysses S Grant, through to Paul von Hindenburg – his ‘iron mask and rock-firm figure became an inalienable possession of the nation’ – and Dwight D Eisenhower. Others used the immense stature gained from victory in war to intrude into politics whenever they fancied: I much enjoyed reading of Montgomery’s ‘trenchant contributions’ to debates in the House of Lords in his old age, ‘delivered from somewhere near the exact centre of the Conservative benches but often turning his own front bench colleagues pale with apprehension.’

For all of us who love reading history, these assessments of such pivotal figures are full of fascination, covering as they do the full sweep of military history over the last two hundred years. It is impossible to read them without reflecting on the inability of most of these extraordinary people to foretell even the immediate future. Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher is something of an exception with his prediction in 1910 that ‘war will come in 1914 and Jellicoe will command the Grand Fleet’, but it is more telling that Hindenburg initially retired in 1911 believing that he would never have the chance to serve in wartime and MacArthur confidently informed President Truman in 1950 that the Chinese were unlikely to intervene in Korea with any force. The sharp turns taken by history are often a shock to the most brilliant of minds.

These men’s minds were, however, well attuned to combining the pursuit of an overall strategy with the rapid taking of decisions under extreme pressure: abilities which distinguish the mind suited to executive command from one better devoted to campaigning or commentating. This above all is why we politicians must treat these figures with reverence, as a reading of the pages devoted to Britain’s military leaders in the First World War shows well. For there we find Allenby winning the war against Turkey over a vast area of the Middle East with a strategy of which ‘the original conception, the patience in preparation, the rapidity and audacity in execution, prove that [he] was a true master of war’.

There too is Admiral Beatty, boldly and suddenly taking his battle-cruisers into the Heligoland Bight to achieve victory when a more cautious leader would have held back, and then his colleague Jellicoe, whose command of the Fleet gave him, according to Churchill, responsibilities on a different scale from all others: ‘the only man on either side who could lose the War in an afternoon’. It is just as well, as his obituary writer notes with approval, that his life had moulded him specifically for such duty, particularly as ‘he did not know in earlier years the softening influences of money or friends in high places’.

Obituaries are necessarily history as it was seen and understood at certain moments, and are often kinder than the subsequent judgement of later decades, but they have the advantage of dealing with the whole life of an individual whom we are used to reading about only at the peak of their career. Many of us will have read of the brilliance of Marshal Zhukov as he led the Soviet armies in the destruction of the Third Reich; we may have overlooked the fact that both Stalin and Krushchev rubbished his achievements and that he had to wait until 1965 before he could appear in public at a military parade and receive a ‘special burst of applause’.

Whether hailed or derided by their contemporaries, these are the stories of great men. Many of them, of course, would have considered themselves such at the time. When Montgomery was asked to name the three greatest generals in history, he replied ‘the other two were Alexander the Great and Napoleon’. So as we enjoy their lives afresh, with all their fascination and inspiration, we can be sure they would have wanted and expected us to do so.

INTRODUCTION Major-General Michael Tillotson (#ulink_42bd7eb1-f6ff-5184-9f1b-c9be79e5fc6e)

THIS COLLECTION OF great military lives spanning the decades from Waterloo to the South Atlantic campaign of 1982 reflects dramatic changes in the scale and much of the nature of war. It begins during the era when national armies or navies marched or sailed out to fight the army or navy of an adversary – in a manner advanced only in magnitude from when David challenged Goliath on behalf of his tribe – the outcome of the battle determining the politics of the matter, possibly for decades. Conflicts then expanded dimensionally, economically and socially to a point where the whole engine of the state became engaged, as with the Civil War in the United States – arguably the first modern industrial war.

Despite the speed of his defeats of Austria in 1866 and France in 1870, Field Marshal von Moltke warned Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1890 that the next war might last between seven and thirty years. He argued that the resources of modern states were so great that none would accept defeat in one campaign or major battle as fair cause for capitulation, but would fight on. He was right in the sense that the war that began in 1914 was not finally concluded until 1945. The scale of manpower involvement in land warfare increased dramatically in the years up to 1914, with the German General Staff planning to use the younger reservists – 23 to 28- year olds – to provide the strength required to envelop the French left flank under the Schlieffen Plan. Forewarned, the French looked to their younger reserves, while Britain founded the Territorial Army.

At the outset of the twentieth century the advent of the submarine, the torpedo and the mine upset the supremacy of the line-of-battle fleet that had persisted from the age of sail well into the age of steam. Naval commanders in this collection were therefore confronted with unprecedented challenges in their conduct of maritime operations. Nuclear powered attack and ballistic missile submarines, for the first time true submersibles – as they do not have to ‘come up for air’ – have now added a new dimension to naval warfare.

The two most significant additions to the established disciplines of war on land and sea are those of air power and the means of acquiring intelligence. In the First World War, air power was a welcome ‘add-on’ for observation, supporting fire and keeping the enemy air force from interfering with surface operations. In the course of a mere twenty years it had developed into a battle-winning or losing factor, as demonstrated in the 1940 German blitzkrieg in France, the extraordinary success of the Japanese expansionist campaign after Pearl Harbour and the critical advantage of the virtually complete Allied air-superiority over northern France in 1944.

In the field of intelligence acquisition, air reconnaissance allowed surface commanders to see the other side of the hill and over the horizon in a time scale within which they could react with profit. The targeting of aerial reconnaissance and subsequent assault onto an enemy’s dispositions, deployments, industrial capacity and surface communications has been enhanced by being able to intercept and decode his strategic and tactical signal traffic. ‘We had an ally,’ crowed Ludendorff’s Deputy Chief of Operations after victory at Tannenberg, ‘The enemy. We knew all the enemy’s plans.’ He had had the daily intercepts of the Russian wireless messages decoded by a German professor of mathematics. The most quantum leap of all is being able to overhear an enemy’s political and strategic discussions and plans, lifting intelligence to a level remote from travellers’ tales and dependence on reports from agents, who could see or hear only one fragment of the plot and who might be working for the enemy.

After the two World Wars, revulsion of the prospect of more carnage and devastation led to ‘limited wars’, limited by geography and objective, such as were fought by the United Nations in Korea and by the United Kingdom against Argentina for the Falkland Islands, yet with the spectre of superpower conflict still hovering ominously in the background, imposing its own constraints on national manoeuvre and aspiration.

Throughout this era of change has lain the menace of ‘undeclared’ war, where there is no formal understanding between adversaries, no acknowledged code for the treatment of prisoners or the wounded and the civilian population is utilized – often ruthlessly – as a place of refuge, a source of support and supply or, worst of all, as hostages upon which atrocities are committed in order to apply restraint or to exact revenge. There is nothing new here and methods vary only with the terrain and the weaponry available to the antagonists. While we might applaud examples like the Spanish guerrilla attacks on the outposts of Napoleon’s armies in the Iberian Peninsula and Tito’s partisans against the Axis occupiers of Yugoslavia, we deplore the murder and mayhem imposed by Kenya’s Mau-Mau or by communist insurgents seeking to overthrow colonial administrations or their perceived proxies in South East Asia. ‘One man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter’ loses none of its truth through having become a cliché. A number of the individuals whose obituaries appear here experienced conflict in several of the forms described, maintaining their reputations for success only when they adapted to change.

Change in the manner in which command is exercised has been equally dramatic. At Waterloo, where this book begins, Wellington commanded in the saddle from where he could oversee events only to the limit of visibility, while inspiring his soldiers by his overt presence. During the war for the Falklands, Admiral Fieldhouse commanded from his bunker deep below the London suburb of Northwood, from where he had access to the latest electronic and satellite intelligence, one-to-one communication with commanders at sea and eventually ashore, and with the British War Cabinet through the filter of the Service Chiefs of Staff.

The most significant aspect of the evolution of command is the extent to which political control may be applied to a commander in the field or at sea, affecting his strategic and even tactical decisions. He may jib at such restrictions, but the international nature of today’s world demands he should be kept alert to political intentions and reservations. From Kitchener’s ‘press conference’ after Omdurman (‘Get out of my way, you drunken swabs’) to to-day, the military commander has had to take increasing account of a pervasive, influential and technically proficient media. This raises the issue of whether one individual might any longer be able to make a critical impact on the outcome of a battle or campaign. The answer is ‘probably yes, but to a lesser extent than formerly’.

These obituaries have been selected from those published in The Times that illustrate high command in war, long experience of armed conflict or preparation for such responsibility. Success or failure has played a smaller part than impact or influence on events at the time and in consequence on the course of history. Some who held high command also pioneered or exploited a significant aspect of war – of which Admirals Dönitz and Horton are examples for submarine warfare and Generals Guderian and Patton for fast-moving armoured penetration and encirclement. We have also included Giuseppe Garibaldi as an exponent of irregular warfare and General Walter Walker as an expert on its suppression. Chiefs Cetywayo and Sitting Bull are here for their prowess as leaders of warrior nations, their courage and methods of warfare beset and eventually defeated by technology.

Objections over omissions and even some inclusions are inevitable, but a balance of different aspects of warfare, geography and nationality had to be struck. A few who might have qualified had no obituary in The Times; otherwise Admiral Thomas Cochrane, Lord Dundonald, (1775–1860) would be here. While a long extract from Wellington’s obituary is included, the death of his great adversary, Napoleon, occurred too early and at a time when The Times had not yet developed its obituary coverage. Lord Kitchener is omitted because his obituary appeared in full in Great Lives, published in 2005. Sadly, no woman could be found to match the criteria for inclusion.

In addition to the conduct of war, its reporting in newspapers and recording in obituaries of the participants have also evolved. News of the victory of Waterloo had to be galloped to and sailed across the Channel while only fifty years later William Russell had his reports on the failings of the staff and administrative services in the Crimea telegraphed to The Times for publication next day – and with little or no censorship imposed upon his copy. Such journalistic freedom, although doubtless available, was seldom exercised in the obituaries of the period. Lord Raglan, who died aged sixty-six while in command of the British Army in the Crimea, whose obituary we include, was unsuited by age and lack of command experience for the responsibilities he held, something recognised by the press and public alike. Yet his obituary concentrates chiefly on his gentlemanly personal qualities, making only the briefest genuflexion towards the awareness of his shortcomings as a field commander at the very end – and without venturing to suggest what they were.

Such courteous restraint shows signs of fraying at the edges as time wore on. First World War commanders are spared some frank criticism possibly out of consideration of the appalling circumstances they faced as well as in the interests of ‘good taste’. Examples are the obituaries of Jellicoe, Beatty and Fisher whose controversies are gently alluded to but not clearly explained. The obituaries of commanders who died soon after their famous deeds tend to reflect current public perception rather than their true worth. Rommel who died in October 1944 before the end of the war in Europe was in sight is granted only grudging praise for his generalship. The treatment – in terms of detail and scope – of the lives and achievements of the selected individuals over the period shows little consistency. One is left to conclude that as much depended on the whim of the Editor of The Times as on the stature of the subject.

Some instances of contrasting coverage lack explanation – for example over 7,000 words for General Ulysses S. Grant against only 1,200 for his strategic equal General Robert E. Lee cannot be wholly attributed to Grant’s subsequent unexciting performance as his country’s eighteenth president. Astonishingly broad coverage was afforded to the Italian soldier-patriot General Giuseppe Garibaldi, over two issues of The Times on June 3rd and 5th 1882, seemingly reflecting the extent to which this romantic – not to say romanticised – figure had been taken into the bosom of Victorian Britain. In marked contrast, the hero of the native American people – Chief Sitting Bull, whose Prairie Sioux tribes took part in the defeat of General Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn – is dismissed in less than a thousand words, as is General ‘Schneller Heinz’ Guderian, the leading German exponent of armoured warfare in the Second World War. In several instance, for example, Wellington, Grant, Garibaldi, Moltke, MacMahon and Eisenhower, the extreme length of the published obituaries have obliged us to include only selected extracts in the book.

Political bias occasionally shows its hand. The obituary for Cetywayo – in a tract of breath-taking Victorian humbug – seeks to portray as a villain the Chief who sought only to protect his tribal lands from annexation and his proud Zulu nation from conquest. In an instance of ‘political correctness’, the lugubrious Field Marshal Paul von Hinden-burg is accorded generous accolades as ‘Father of the Fatherland’ on the occasion of his death a bare eighteen months after being obliged to install Hitler as German Chancellor, causing widespread alarm across Europe. That for General Douglas MacArthur concentrates dispro-portionately on the Korean War and the terms of his removal, at the expense of the strategic vision of his Pacific campaign and his personal courage.

In order to provide a balanced perspective when an obituary lacks historical or strategic context, appears to fall short of the credit a subject is due, omits mention of important events or glosses over a controversy with which the subject was associated, my naval colleague – Rear-Admiral Guy Liardet – and I have added our comments. Explanations have been added when the writer of the obituary assumed the reader’s familiarity with the role of persons mentioned only by name or with then recent but now largely forgotten events. Occasionally, touches of light-heartedness have been added to lift an otherwise over-solemn account.

A search for a common element or thread in the lives of those included often reveals a humble or relatively humble background, although this is by no means always so; hardship in the formative years – resulting in an enduring code of self-discipline – and most significant of all, a strong sense of public service, one that eschews personal profit or honours. Former tanner General Ulysses S. Grant, Marshal Gustaf Mannerheim – second son of a minor nobleman, as a boy obliged to speak a different European language each weekday-Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher, born in Ceylon, his father a junior infantry officer, entered a Victorian Navy ‘penniless and forlorn’ as he was fond of saying and the peasant, former cavalry sergeant Georgi Zhukov are the more obvious examples. There are exceptions: Earl Beatty combined privilege with an intense ambition.

The variation in the language of the obituaries over one and a half centuries illuminates the changes in public attitude to the great and perhaps not-so-good and in the fashion of writing structure, punctuation and use of words. In the 19th and early 20th century examples, failings are not so much left to be read between the lines as approached in the manner of ‘grandmother’s footsteps’, with the stalker seemingly losing nerve at the last moment, leaving grandmother to reach her final destination without being openly caught out. Sentences of inordinate length, spattered with commas, colons and dashes with the generous impartiality of grape-shot were commonplace in that period. Some obituary writers had apparently never received an introduction to the paragraph, resulting in difficult-to-digest long, descending barrels of words. In the latter instances only, paragraphs have been imposed but otherwise the obituaries have been taken directly from The Times, retaining the original punctuation and spelling.

The sequence in which to present the obituaries allowed several options. The convenience of alphabetical order lacked imagination, while a chronology based on achievement of fame or the order of birth or death threw up awkward anomalies. Consequently, those associated with some great historical event, such as the two World Wars, have been grouped together and individuals whose names will be for ever linked – Jellicoe with Beatty over the Battle of Jutland and MacArthur with Nimitz in the war in the Pacific are put in immediate succession – all, it is hoped, without losing the possibility of a serendipitous moment as the reader casually turns the page. These lives are a part of history and their study an aid to its understanding.

WELLINGTON (#ulink_6e755062-4c4e-58af-a95e-483ec803584d)

Strategist and inspirational commander-in-chief

15TH SEPTEMBER 1852

This extract taken from The Times of 15th September 1852 describes The Duke of Wellington’s conduct of the war in the Iberian Peninsula. Appreciations of his command during the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and as Prime Minister 1828–1830 appear in the concluding commentary.

ENGLAND WAS NOW at the commencement of her greatest war. The system of small expeditions and insignificant diversions, though not yet conclusively abandoned, was soon superseded by the glories of a visible contest; and in a short time it was known and felt by a great majority of the nation that on the field of the Peninsula England was fairly pitted against France, and playing her own chosen part in the European struggle. But these convictions were not prevalent enough at the outset to facilitate in any material degree the duties of the Ministry or the work of the General; on the contrary, so complicated were the embarrassments attending the prosecution of the war on the scale required, that to surmount them demanded little less wisdom or patience than the conduct of the actual campaign. In the first instance the British nation had been extravagantly excited by the successful insurrections of the Spaniards, and the events of our experimental campaign in Portugal had so inspirited the public mind that even the evacuation of that kingdom by the French was considered, as we have seen, in the light of an imperfect result. When, however, these conditions of the struggle were rapidly exchanged for the total discomfiture of the patriots, the recapture of Madrid, and the precipitate retreat of the British army, with the loss of its commander and the salvation of little but its honour, popular opinion veered quickly towards its customary point, and it was loudly proclaimed that the French Emperor was invincible by land, and that a contest with his legions on that element must inevitably prove ruinous to Britain. But the Government of the day, originally receiving its impulse from public feeling, had gradually acquired independent convictions on this mighty question, and was now prepared to maintain the interests of the nation against the clamours of the nation itself. Accordingly, at the commencement of the year 1809, when the prospects of Spanish independence were at their very gloomiest point, the British Cabinet had proposed and concluded a comprehensive treaty of alliance with the Provisional Administration of Spain; and it was now resolved that the contest in the Peninsula should be continued on a scale more effectual than before, and that the principal, instead of the secondary, part should be borne by England. Yet this decision was not taken without much hesitation and considerable resistance; and it was clear to all observant spectators that, though the opinions of the Government, rather than those of the Opposition, might preponderate in the public mind, their ascendancy was not so complete but that the first incidents of failure, loss, or difficulty, would be turned to serious account against the promoters and conductors of the war.

Nor were these misgivings, though often pretended for the purposes of faction, without a certain warrant of truth; indeed, few can read the history of this struggle without perceiving that the single point which concluded it in our favour was the genius of that great man who has just expired. It has been attempted to show that the military forces of France and England at this period were not in reality so disproportioned as they appeared to be, but we confess our own inability to discover the balance alleged. It is beyond doubt that the national spirit remained unchanged, and that the individual excellence of the British soldier was unimpeachable. Much, too, had been done in the way of organization by the measures consequent on the protracted menace of invasion, and much in the way of encouragement by the successes in Egypt and Portugal no less than the triumphs in India. But in war numerical force must needs tell with enormous effect, and on this point England’s colonial requirements left her little to show against the myriads of the continent. It was calculated at the time that 60,000 British soldiers might have been made disposable for the Peninsular service, but at no period of the war was such a force ever actually collected under the standards of Wellington, while Napoleon could maintain his 300,000 warriors in Spain, without disabling the arms of the Empire on the Danube or the Rhine. We had allies, it is true, in the troops of the country; but these at first were little better than refractory recruits, requiring all the accessories of discipline, equipment, and organization; jealous of all foreigners even as friends, and not unreasonably suspicious of supporters who could always find in their ships a refuge which was denied to themselves. But above all these difficulties was that arising from the inexperience of the Government in continental warfare. Habituated to expeditions reducible to the compass of a few transports, unaccustomed to the contingencies of regular war, and harassed by a vigilant and not always conscientious Opposition, the Ministry had to consume half its strength at home; and the commander of the army, in justifying his most skilful dispositions, or procuring needful supplies for the troops under his charge, was driven to the very extremities of expostulation and remonstrance.

When, however, with these ambiguous prospects, the Government did at length resolve on the systematic prosecution of the Peninsular war, the eyes of the nation were at once instinctively turned on Sir Arthur Wellesley as the general to conduct it. Independently of the proofs he had already given of his quality at Roliça and Vimiera this enterprising and sagacious soldier stood almost alone in his confidence respecting the undertaking on hand. Arguing from the military position of Portugal, as flanking the long territory of Spain, from the natural features of the country (which he had already studied), and from the means of reinforcement and retreat securely provided by the sea, he stoutly declared his opinion that Portugal was tenable against the Fench, even if actual possessors of Spain, and that it offered ample opportunities of influencing the great result of the war. With these views he recommended that the Portuguese army should be organized at its full strength; that it should be in part taken into British pay and under the direction of British officers, and that a force of not less than 30,000 English troops should be despatched to keep this army together. So provided, he undertook the management of the war, and such were his resources, his tenacity, and his skill, that though 280,000 French soldiers were closing round Portugal as he landed at Lisbon, and though difficulties of the most arduous kind awaited him in his task, he neither flinched nor failed until he had led his little army in triumph, not only from the Tagus to the Ebro, but across the Pyrenees into France, and returned himself by Calais to England after witnessing the downfall of the French capital.

Yet, so perilous was the conjuncture when the weight of affairs was thus thrown upon his shoulders that a few weeks’ more delay must have destroyed every prospect of success. Not only was Soult, as we stated, collecting himself for a swoop on the towers of Lisbon, but the Portuguese themselves were distrustful of our support, and the English troops while daily preparing for embarkation, were compelled to assume a defensive attitude against those whose cause they were maintaining. But such was the prestige already attached to Wellesley’s name that his arrival in the Tagus changed every feature of the scene. No longer suspicious of our intentions, the Portuguese Government gave prompt effect to the suggestions of the English commander; levies were decreed and organized, provisions collected, depôts established, and a spirit of confidence again pervaded the country, which was unqualified on this occasion by that jealous distrust which had formerly neutralized its effects. The command in chief of the native army was intrusted to an English officer of great distinction, General Beresford, and no time was lost in once more testing the efficacy of the British arms.

Our description of the positions relatively occupied by the contending parties at this juncture will, perhaps, be remembered. Soult, having left Ney to control the north, was at Oporto with 24,000 men, preparing to cross the Douro and descend upon Lisbon, while Victor and Lapisse, with 30,000 more, were to co-operate in the attack from the contiguous provinces of Estremadura and Leon. Of the Spanish armies we need only say that they had been repeatedly routed with more or less disgrace, though Cuesta still held a certain force together in the valley of the Tagus. There were therefore two courses open to the British commander – either to repel the menaced advance of Soult by marching on Oporto or to effect a junction with Cuesta, and try the result of a demonstration upon Madrid. The latter of these plans was wisely postponed for the moment, and, preference having been decisively given to the former, the troops at once commenced their march upon the Douro. The British force under Sir Arthur Wellesley’s command amounted at this time to about 20,000 men, to which about 15,000 Portuguese in a respectable state of organization were added by the exertions of Beresford. Of these about 24,000 were now led against Soult, who, though not inferior in strength, no sooner ascertained the advance of the English commander than he arranged for a retreat by detaching Loison with 6,000 men to dislodge a Portuguese post in his left rear. Sir Arthur’s intention was to envelop, if possible, the French corps by pushing forward a strong force upon its left, and then intercepting its retreat towards Ney’s position, while the main body assaulted Soult in his quarters at Oporto. The former of these operations he intrusted to Beresford, the latter he directed in person. On the 12th of May the troops reached the southern bank of the Douro; the waters of which, 300 yards in width, rolled between them and their adversaries. In anticipation of the attack Soult had destroyed the floating-bridge, had collected all the boats on the opposite side, and there, with his forces well in hand for action or retreat, was looking from the window of his lodging, enjoying the presumed discomfiture of his opponent. To attempt such a passage as this in face of one of the ablest marshals of France was, indeed, an audacious stroke, but it was not beyond the daring of that genius which M. Thiers describes as calculated only for the stolid operations of defensive war. Availing himself of a point where the river by a bend in its course was not easily visible from the town, Sir Arthur determined on transporting, if possible, a few troops to the northern bank, and occupying an unfinished stone building, which he perceived was capable of affording temporary cover. The means were soon supplied by the activity of Colonel Waters – an officer whose habitual audacity rendered him one of the heroes of this memorable war. Crossing in a skiff to the opposite bank, he returned with two or three boats, and in a few minutes a company of the Buffs was established in the building. Reinforcements quickly followed, but not without discovery. The alarm was given, and presently the edifice was enveloped by the eager battalions of the French. The British, however, held their ground; a passage was effected at other points during the struggle; the French, after an ineffectual resistance, were fain to abandon the city in precipitation, and Sir Arthur, after his unexampled feat of arms, sat down that evening to the dinner which had been prepared for Soult. Nor did the disasters of the French marshal terminate here, for, though the designs of the British commander had been partially frustrated by the intelligence gained by the enemy, yet the French communications were so far intercepted, that Soult only joined Ney after losses and privations little short of those which had been experienced by Sir John Moore.

This brilliant operation being effected, Sir Arthur was now at liberty to turn to the main project of the campaign – that to which, in fact, the attack upon Soult had been subsidiary – the defeat of Victor in Estremadura; and, as the force under this marshal’s command was not greater than that which had been so decisively defeated at Oporto, some confidence might naturally be entertained in calculating upon the result. But at this time the various difficulties of the English commander began to disclose themselves. Though his losses had been extremely small in the recent actions, considering the importance of their results, the troops were suffering severely from sickness, at least 4,000 being in hospital, while supplies of all kinds were miserably deficient through the imperfections of the commissariat. The soldiers were nearly barefooted, their pay was largely in arrear, and the military chest was empty. In addition to this, although the real weakness of the Spanish armies was not yet fully known, it was clearly discernible that the character of their commanders would preclude any effective concert in the joint operations of the allied force. Cuesta would take no advice, and insisted on the adoption of his own schemes with such obstinacy that Sir Arthur was compelled to frame his plans accordingly. Instead, therefore, of circumventing Victor as he had intended, he advanced into Spain at the beginning of July, to effect a junction with Cuesta and feel his way towards Madrid. The armies, when united, formed a mass of 78,000 combatants, but of these 56,000 were Spanish, and for the brunt of war Sir Arthur could only reckon on his 22,000 British troops, Beresford’s Portuguese having been despatched to the north of Portugal. On the other side, Victor’s force had been strengthened by the succours which Joseph Bonaparte, alarmed for the safety of Madrid, had hastily concentrated at Toledo; and when the two armies at length confronted each other at Talavera it was found that 55,000 excellent French troops were arrayed against Sir Arthur and his ally, while nearly as many more were descending from the north on the line of the British communications along the valley of the Tagus. On the 28th of July the British Commander, after making the best dispositions in his power, received the attack of the French, directed by Joseph Bonaparte in person, with Victor and Jourdan at his side, and after an engagement of great severity, in which the Spaniards were virtually inactive, he remained master of the field against double his numbers, having repulsed the enemy at all points with heavy loss, and having captured several hundred prisoners and 17 pieces of cannon in this the first great pitched battle between the French and English in the Peninsula.

In this well fought field of Talavera the French had thrown, for the first time, their whole disposable force upon the British army without success, and Sir Arthur Wellesley inferred with a justifiable confidence that the relative superiority of his troops to those of the Emperor was practically decided. Jomini, the French military historian, confesses almost as much, and the opinions of Napoleon himself, as visible in his correspondence, underwent from that moment a serious change. Yet at home the people, wholly unaccustomed to the contingencies of a real war, and the Opposition, unscrupulously employing the delusions of the people, combined in decrying the victory, denouncing the successful general, and despairing of the whole enterprise. The city of London even recorded on a petition its discontent with the ‘rashness, ostentation, and useless valour’ of that commander whom M. Thiers depicts as endowed solely with the sluggish and phlegmatic tenacity of his countrymen; and, though Ministers succeeded in procuring an acknowledgment of the services performed, and a warrant for persisting in the effort, both they and the British General were sadly cramped in the means of action. Sir Arthur Wellesley became, indeed, ‘Baron Douro, of Wellesley, and Viscount Wellington of Talavera, and of Wellington, in the county of Somerset,’ but the Government was afraid to maintain his effective means even at the moderate amount for which he had stipulated, and they gave him plainly to understand that the responsibility of the war must rest upon his own shoulders. He accepted it, and, in full reliance on his own resources and the tried valour of his troops, awaited the shock which was at hand. The battle of Talavera acted on the Emperor Napoleon exactly like the battle of Vimiera. His best soldiers had failed against those led by the ‘Sepoy General,’ and he became seriously alarmed for his conquest of Spain. After Vimiera he rushed, at the head of his guards, through Somosierra to Madrid; and now, after Talavera, he prepared a still more redoubtable invasion. Relieved from his continental liabilities by the campaigns of Aspern and Wagram, and from nearer apprehensions by the discomfiture of our expedition to Walcheren, he poured his now disposable legions in extraordinary numbers through the passes of the Pyrenees. Nine powerful corps, mustering fully 280,000 effective men, under Marshals Victor, Ney, Soult, Mortier, and Massena, with a crowd of aspiring generals besides, represented the force definitely charged with the final subjugation of the Peninsula. To meet the shock of this stupendous array Wellington had the 20,000 troops of Talavera augmented, besides other reinforcements, by that memorable brigade which, under the name of the Light Division, became afterwards the admiration of both armies. In addition, he had Beresford’s Portuguese levies, now 30,000 strong, well disciplined, and capable, as events showed, of becoming first-rate soldiers, making a total of some 55,000 disposable troops, independent of garrisons and detachments. All hopes of effectual co-operation from Spain had now vanished. Disregarding, the sage advice of Wellington, the Spanish generals had consigned themselves and their armies to inevitable destruction, and of the whole kingdom, Gibraltar and Cadiz alone had escaped the swoop of the victorious French. The Provisional Administration displayed neither resolution nor sincerity, the British forces were suffered absolutely to starve, and Wellington was unable to extort from the leaders around him the smallest assistance for that army which was the last support of Spanish freedom. It was under such circumstances, with forces full of spirit, but numerically weak, without any assurance of sympathy at home, without money or supplies on the spot, and in the face of Napoleon’s best marshal, with 80,000 troops in line, and 40,000 in reserve, that Wellington entered on the campaign of 1810 – a campaign pronounced by military critics to be inferior to none in his whole career.

Withdrawing, after the victory of Talavera, from the concentrating forces of the enemy attracted by his advance, he had at first taken post on the Guadiana, until, wearied out by Spanish insincerity and perverseness, he moved his army to the Mondego, preparatory to those encounters which he foresaw the defence of Portugal must presently bring to pass. Already had he divined by his own sagacity the character and necessities of the coming campaign. Massena, as the best representative of the Emperor himself, having under his orders Ney, Regnier, and Junot, was gathering his forces on the north-eastern frontier of Portugal to fulfil his master’s commands by ‘sweeping the English leopard into the sea.’ Against such hosts as he brought to the assault a defensive attitude was all that could be maintained, and Wellington’s eye had detected the true mode of operation. He proposed to make the immediate district of Lisbon perform that service for Portugal which Portugal itself performed for the Peninsula at large, by furnishing an impregnable fastness and a secure retreat. By carrying lines of fortification from the Atlantic coast, through Torres Vedras, to the bank of the Tagus a little above Lisbon, he succeeded in constructing an artificial stronghold within which his retiring forces would be inaccessible, and from which, as opportunities invited, he might issue at will. These provisions silently and unobtrusively made, he calmly took post on the Coa, and awaited the assault. Hesitating or undecided, from some motive or other, Massena for weeks delayed the blow, till at length, after feeling the mettle of the Light Division on the Coa, he put his army in motion after the British commander, who slowly retired to his defences. Deeming, however, that a passage of arms would tend both to inspirit his own troops in what seemed like a retreat, and to teach Massena the true quality of the antagonist before him, he deliberately halted at Busaco and offered battle. Unable to refuse the challenge, the French marshal directed his bravest troops against the British position, but they were foiled with immense loss at every point of the attack, and Wellington proved, by one of his most brilliant victories, that his retreat partook neither of discomfiture nor fear. Rapidly recovering himself, however, Massena followed on his formidable foe, and was dreaming of little less than a second evacuation of Portugal, when, to his astonishment and dismay, he found himself abruptly arrested in his course by the tremendous lines of Torres Vedras.

These prodigious intrenchments comprised a triple line of fortifications one within the other, the innermost being intended to cover the embarcation of the troops in the last resort. The main strength of the works had been thrown on the second line, at which it had been intended to make the final stand, but even the outer barrier was found in effect to be so formidable as to deter the enemy from all hopes of a successful assault. Thus checked in mid career, the French marshal chafed and fumed in front of these impregnable lines, afraid to attack, yet unwilling to retire. For a whole month did he lie here inactive, tenacious of his purpose, though aware of his defeat, and eagerly watching for the first advantage which the chances of war or the mistakes of the British general might offer him. Meantime, however, while Wellington’s concentrated forces were enjoying, through his sage provisions, the utmost comfort and abundance within their lines, the French army was gradually reduced to the last extremities of destitution and disease, and Massena at length broke up in despair, to commence a retreat which was never afterwards exchanged for an advance. Confident in hope and spirit, and overjoyed to see retiring before them one of those real Imperial armies which had swept the continent from the Rhine to the Vistula, the British troops issued from their works in hot pursuit, and, though the extraordinary genius of the French commander preserved his forces from what in ordinary cases would have been the ruin of a rout, yet his sufferings were so extreme and his losses so heavy that he carried to the frontier scarcely one-half of the force with which he had plunged blindly into Portugal. Following up his wary enemy with a caution which no success was permitted to disturb, Wellington presently availed himself of his position to attempt the recovery of Almeida, a fortress which, with Ciudad Rodrigo, forms the key of north-eastern Portugal, and which had been taken by Massena in his advance. Anxious to preserve this important place, the French marshal turned with his whole force upon the foe, but Wellington met him at Fuentes d’Onoro, repulsed his attempts in a sanguinary engagement, and Almeida fell.

As at this point the tide of French conquest had been actually turned, and the British army, so lightly held by Napoleon, was now manifestly chasing his eagles from the field, it might have been presumed that popularity and support would have rewarded the unexampled successes of the English general. Yet it was not so. The reverses experienced during the same period in Spain were loudly appealed to as neutralizing the triumphs in Portugal, and at no moment was there a more vehement denunciation of the whole Peninsular war. Though Cadiz resolutely held out, and Graham, indeed, on the heights of Barossa, had emulated the glories of Busaco, yet even the strong fortress of Badajoz had now fallen before the vigorous audacity of Soult; and Suchet, a rising general of extraordinary abilities, was effecting by the reduction of hitherto impregnable strongholds the complete conquest of Catalonia and Valencia. Eagerly turning these disasters to account, and inspirited by the accession of the Prince Regent to power, the Opposition in the British Parliament so pressed the Ministry, that at the very moment when Wellington, after his unrivalled strategy, was on the track of his retreating foe, he could scarcely count for common support on the Government he was serving. He was represented in England, as his letters show us, to be ‘in a scrape,’ and he fought with the consciousness that all his reverses would be magnified and all his successes denied. Yet he failed neither in heart nor hand. He had verified all his own assertions respecting the defensibility of Portugal. His army had become a perfect model in discipline and daring, he was driving before him 80,000 of the best troops of the Empire, and he relied on the resources of his own genius for compensating those disadvantages to which he foresaw he must be still exposed. Such was the campaign of 1810, better conceived and worse appreciated than any which we shall have to record.

As the maintenance of Portugal was subsidiary to the great object of the war, the deliverance of the Peninsula from French domination – Wellington of course proceeded, after successfully repulsing the invaders from Portuguese soil, to assume the offensive, by carrying his arms into Spain. Thus, after defeating Junot, he had been induced to try the battle of Talavera; and now, after expelling Massena, he betook himself to similar designs, with this difference that instead of operating by the valley of the Tagus against Madrid, he now moved to the valley of the Guadiana for the purpose of recovering Badajoz, a fortress, like that of Ciudad Rodrigo, so critically situated on the frontier, that with these two places in the enemy’s hands, as they now were, it became hazardous either to quit Portugal or to penetrate into Spain. At this point, therefore, were now to commence the famous sieges of the Peninsula – sieges which will always reflect immortal honour on the troops engaged, and which will always attract the interest of the English reader; but which must, nevertheless, be appealed to as illustrations of the straits to which an army may be led by want of military experience in the Government at home. By this time the repeated victories of Wellington and his colleagues had raised the renown of British soldiers to at least an equality with that of Napoleon’s veterans, and the incomparable efficiency, in particular, of the light division was acknowledged to be without a parallel in any European service. But in those departments of the army where excellence is less the result of intuitive ability, the forces under Wellington were still greatly surpassed by the trained legions of the Emperor. While Napoleon had devoted his whole genius to the organization of the parks and trains which attend the march of an army in the field, the British troops had only the most imperfect resources on which to rely. The Engineer corps, though admirable in quality, was so deficient in numbers that commissions were placed at the free disposal of Cambridge mathematicians. The siege trains were weak and worthless against the solid ramparts of Peninsular strongholds, the intrenching tools were so ill made that they snapped in the hands of the workmen, and the art of sapping and mining was so little known that this branch of the siege duties was carried on by draughts from the regiments of the line, imperfectly and hastily instructed for the purpose. Unhappily, these results can only be obviated by long foresight, patient training, and costly provision; it was not in the power of a single mind, however capacious, to effect an instantaneous reform, and Wellington was compelled to supply the deficiencies by the best blood of his troops.

The command of the force commissioned to recover Badajoz had been intrusted to Marshal Beresford until Lord Wellington could repair in person to the scene, and it was against Soult, who was marching rapidly from the south to the relief of the place, that the glorious but sanguinary battle of Albuera was fought on the 16th of May. Having checked the enemy by this bloody defeat Beresford resumed the duties of the siege until he was superseded by the Commander-in-Chief. But all the efforts of Wellington and his troops were vain, for the present, against this celebrated fortress; two assaults were repulsed, and the British general determined on relinquishing the attempt, and returning to the northern frontier of Portugal for more favourable opportunities of action. He had now by his extraordinary genius so far changed the character of the war, that the British, heretofore fighting with desperate tenacity for a footing at Lisbon or Cadiz, were now openly assuming the offensive, and Napoleon had been actually compelled to direct defensive preparations along the road leading through Vittoria to Bayonne – that very road which Wellington in spite of these defences was soon to traverse in triumph. Meantime fresh troops were poured over the Pyrenees into Spain, and a new plan of operations was dictated by the Emperor himself. One powerful army in the north was to guard Castile and Leon, and watch the road by which Wellington might be expected to advance; another, under Soult, strongly reinforced, was to maintain French interests in Andalusia and menace Portugal from the south; while Marmont, who had succeeded Massena, took post with 30,000 men in the valley of the Tagus, resting on Toledo and Madrid, and prepared to concert movements with either of his colleagues as occasion might arise. To encounter these antagonists, who could rapidly concentrate 90,000 splendid troops against him, Wellington could barely bring 50,000 into the field; and though this disparity of numbers was afterwards somewhat lessened, yet it is scarcely in reason to expect that even the genius of Wellington or the value of his troops could have ultimately prevailed against such odds but for circumstances which favoured the designs of the British and rendered the contest less unequal. In the first place, the jealousies of the French marshals, when unrepressed by the Emperor’s presence, were so inveterate as to disconcert the best operations, being sometimes little less suicidal than those of the Princes of India. Next, although the Spanish armies had ceased to offer regular resistance to the invaders, yet the guerilla system of warfare, aided by interminable insurrections, acted to the incessant embarrassment of the French, whose duties, perils, and fatigues were doubled by the restless activity of these daring enemies. But the most important of Wellington’s advantages was that of position. With an impregnable retreat at Lisbon, with free water carriage in his rear, and with the great arteries of the Douro and the Tagus for conducting his supplies, he could operate at will from his central fastness towards the north, east, or south. If the northern provinces were temporarily disengaged from the enemy’s presence, he could issue by Almeida and Salamanca upon the great line of communication between the Pyrenees and Madrid; if the valley of the Tagus were left unguarded, he could march directly upon the capital by the well-known route of Talavera; while if Soult, by any of these demonstrations, was tempted to cross the Guadiana, he could carry his arms into Andalusia by Elvas and Badajoz. Relying, too, on the excellence of his troops, he confidently accounted himself a match for any single army of the enemy, – while he was well aware, from the exhausted state of the country and the difficulties of procuring subsistence, no concentration of the French forces could be maintained for many days together. In this way, availing himself of the far superior intelligence which he enjoyed through the agency of the guerillas, and of his own exclusive facilities for commanding supplies, he succeeded in paralysing the enormous hosts of Napoleon, by constant alarms and well-directed blows, till at length when the time of action came he advanced from cantonments and drove King Joseph and all his marshals headlong across the Pyrenees.

The position taken up by Wellington when he transferred his operations from the south to the north frontier of Portugal was at Fuente Guinaldo, a locality possessing some advantageous features in the neighbourhood of Ciudad Rodrigo. His thoughts being still occupied by the means of gaining the border fortresses, he had promptly turned to Rodrigo from Badajoz, and had arranged his plans with a double prospect of success. Knowing that the place was inadequately provisioned he conceived hopes of blockading it into submission from his post at Fuente Guinaldo, since in the presence of this force no supplies could be thrown into the town unless escorted by a convoy equal to the army under his command. Either, therefore, the French marshal must abandon Rodrigo to its fate, or he must go through the difficult operation of concentrating all his forces to form the convoy required. Marmont chose the latter alternative, and uniting his army with that of Dorsenne advanced to the relief of Rodrigo with an immense train of stores and 60,000 fighting men. By this extraordinary effort not only was the place provisioned, but Wellington himself was brought into a situation of some peril, for after successfully repulsing an attempt of the French in the memorable combat of El Bodon he found himself the next day, with only 15,000 men actually at his disposal, exposed to the attack of the entire French army. Fortunately Marmont was unaware of the chance thus offered him, and while he was occupying himself in evolutions and displays Wellington collected his troops and stood once more in security on his position. This movement, however, of the French commander destroyed all hopes of reducing Rodrigo by blockade, and the British general recurred accordingly to the alternative he nad been contemplating of an assault by force.

To comprehend the difficulties of this enterprise, it must be remembered that the superiority of strength was indisputably with the French whenever they concentrated their forces, and that it was certain such concentration would be attempted, at any risk, to save such a place as Rodrigo. Wellington, therefore, had to prepare, with such secrecy as to elude the suspicions of his enemy, the enormous mass of materials required for such a siege as that he projected. As the town stood on the opposite or Spanish bank of the river Agueda, and as the approaches were commanded by the guns of the garrison, it became necessary to construct a temporary bridge. Moreover, the heavy battering train, which alone required 5,000 bullocks to draw it, had to be brought up secretly to the spot, though it was a work almost of impossibility to get a score of cattle together. But these difficulties were surmounted by the inventive genius of the British commander. Preparing his battering train at Lisbon, he shipped it at that port as if for Cadiz, transshipped it into smaller craft at sea, and then brought it up the stream of the Douro. In the next place, he succeeded, beyond the hopes of his engineers, in rendering the Douro navigable for a space of 40 miles beyond the limit previously presumed, and at length he collected the whole necessary materials in the rear of his army without any knowledge on the part of his antagonist. He was now to reap the reward of his precaution and skill. Towards the close of the year the French armies having – conformably to directions of the Emperor, framed entirely on the supposition that Wellington had no heavy artillery – been dispersed in cantonments, the British general suddenly threw his bridge across the Agueda, and besieged Ciudad Rodrigo in force. Ten days only elapsed between the investment and the storm. On the 8th of January, 1812, the Agueda was crossed, and on the 19th the British were in the city. The loss of life greatly exceeded the limit assigned to such expenditure in the scientific calculations of military engineers; but the enterprise was undertaken in the face of a superior force, which could at once have defeated it by appearing on the scene of action; and so effectually was Marmont baffled by the vigour of the British that the place had fallen before his army was collected for its relief. The repetition of such a stroke at Badajoz, which was now Wellington’s aim, presented still greater difficulties, for the vigilance of the French was alarmed, the garrison of the place had been reconstituted by equal draughts from the various armies in order to interest each marshal personally in its relief, and Soult in Andalusia, like Marmont in Castile, possessed a force competent to overwhelm any covering army which Wellington could detach. Yet on the 7th of April Badajoz likewise fell, and after opening a new campaign with these famous demonstrations of his own sagacity and the courage of his troops, he prepared for a third time to advance definitely from Portugal into Spain.

Though the forces of Napoleon in the Peninsula were presently to be somewhat weakened by the requirements of the Russian war, yet at the moment when these strongholds were wrenched from their grasp the ascendancy of the Emperor was yet uncontested, and from the Niemen to the Atlantic there was literally no resistance to his universal dominion save by this army, which was clinging with invincible tenacity to the rocks of Portugal, at the western extremity of Europe. From these well defended lines, however, they were now to emerge, and while Hill, by his surprise of Gerard at Arroyo Molinos and his brilliant capture of the forts at the bridge of Almaraz, was alarming the French for the safety of Andalusia, Wellington began his march to the Pyrenees. On this occasion he was at first unimpeded. So established was the reputation of the troops and their general that Marmont retired as he advanced, and Salamanca, after four years of oppressive occupation, was evacuated before the liberating army. But the hosts into which Wellington had thus boldly plunged with 40,000 troops still numbered fully 270,000 soldiers, and though these forces were divided by distance and jealousies, Marmont had no difficulty in collecting an army numerically superior to that of his antagonist. Returning, therefore, to the contest, and hovering about the English general for the opportunity of pouncing at an advantage upon his troops, he gave promise of a decisive battle, and, after some days of elaborate manoeuvring, the opposing armies found themselves confronted, on the 22d of July, in the vicinity of Salamanica. It was a trial of strategy, but in strategy as well as vigour the French marshal was surpassed by his redoubtable adversary. Seizing with intuitive genius an occasion which Marmont offered, Wellington fell upon his army and routed it so completely that half of its effective force was destroyed in the engagement. So decisively had the blow been dealt, and so skilfully had it been directed, that, as Napoleon had long fortold of such an event, it paralysed the entire French force in Spain, and reduced it to the relative position so long maintained by the English – that of tenacious defence. The only two considerable armies now remaining were those of Suchet in the east, and Soult in the south. Suchet, on hearing of Marmont’s defeat, proposed that the French should make a Portugal of their own in Catalonia, and defend themselves in its fastnesses till aid could arrive from the Pyrenees; while Soult advocated with equal warmth a retirement into Andalusia and a concentration behind the Guadiana. There was little time for deliberation, for Wellington was hot upon his prey, but as King Joseph decamped from his capital he sent orders to Soult to evacuate Andalusia; and the victorious army of the British, after thus, by a single blow, clearing half Spain of its invaders, made its triumphant entry into Madrid.

Wellington was now in possession of the capital of Spain. He had succeeded in delivering that blow which had so long been meditated, and had signalized the crowing ascendancy of his army by the total defeat of his chief opponent in open field. But his work was far from finished, and while all around was rejoicing and triumph, his forecast was anxiously revolving the imminent contingencies of the war. In one sense, indeed, the recent victory had increased rather than lessened the dangers of his position, for it had driven his adversaries by force of common peril into a temporary concert, and Wellington well knew that any such concert would reduce him again to the defensive. Marshal Soult, it was true, had evacuated Andalusia, and King Joseph Madrid; but their forces had been carried to Suchet’s quarters in Valencia, where they would thus form an overpowering concentration of strength; and in like manner, though Marmont’s army had been shorn of half its numbers, it was rapidly recovering itself under Clauzel by the absorption of all the detachments which had been operating in the north. Wellington saw, therefore, that he must prepare himself for a still more decisive struggle, if not for another retreat; and conceiving it most important to disembarrass his rear, he turned round upon Clauzel with the intention of crushing him before he could be fully reinforced, and thus establishing himself securely on the line of the Douro to wait the advance of King Joseph from the east.

With these views, after leaving a strong garrison at Madrid, he put his army in motion, drove Clauzel before him from Valladolid, and on the 18th of September appeared before Burgos. This place, though not a fortification of the first rank, had been recently strengthened by the orders of Napoleon, whose sagacity had divined the use to which its defences might possibly be turned. It lay in the great road to Bayonne, and was now one of the chief depôts retained by the French in the Peninsula, for the campaign had stripped them of Rodrigo, Badajoz, Madrid, Salamanca, and Seville. It became, there fore, of great importance to effect its reduction, and Wellington sat down before it with a force which, although theoretically unequal to the work, might, perhaps, from past recollections, have warranted some expectations of success. But our Peninsular sieges supply, as we have said, rather. warnings than examples. Badajoz and Rodrigo were only won by a profuse expenditure of life, and Burgos, though attacked with equal intrepidity, was not won at all. After consuming no less than five weeks before its walls Wellington gave reluctant orders for raising the siege and retiring. It was, indeed, true for the Northern army, now under the command of Souham, mustered 44,000 men in his rear, and Soult and Joseph were advancing with fully 70,000 more upon the Tagus. To oppose these forces Wellington had only 33,000 troops, Spaniards included, under his immediate command, while Hill, with the garrison of Madrid, could only muster some 20,000 to resist the advance of Soult. The British commander determined, therefore, on recalling Hill from Madrid and resuming his former position on the Agueda – a resolution which he successfully executed in the face of the difficulties around him, though the suffering and discour-agement of the troops during this unwelcome retreat were extremely severe. A detailed criticism of these operations would be beyond our province. It is enough to say that the French made a successful defence, and we have no occasion to begrudge them the single achievement against the English arms which could be contributed to the historic gallery of Versailles by the whole Peninsular War.

Such, however, was in those times the incredulity or perverseness of party spirit in England that, while no successes were rated at their true import, every incomplete operation was magnified into a disaster and describe as a warning. The retreat from Burgos was cited, like the retreat from Talavera, as a proof of the mismanagement of the war, and occasion was taken in Parliament to compare even the victory of Salamanca with the battles of Marlborough to the disparagement of Wellington and his army. Nor did any great enlightenment yet prevail on the subject of military operations; for a considerable force destined to act on the eastern coast of Spain was diverted by Lord William Bentinck to Sicily at a moment when its appearance in Valencia would have disconcerted all the plans of the French, and by providing occupation for Joseph and his marshals have relieved Wellington from that concentration of his enemies before which he was compelled to retire. But neither the wilfulness of faction nor the tenacity of folly could do more than obstruct events which were now steadily in course. Even the inherent obstinacy of Spanish character had at length yielded to the visible genius of Wellington, and the whole military force of the country was now at length, in the fifth year of the war, placed under his paramount command. But these powers were little more than nominal, and, in order to derive an effective support from the favourable dispositions of the Spanish Government, the British general availed himself of the winter season to repair in person to Cadiz.

It will be remembered that when, after the battle of Talavera and the retirement of Wellington to Portugal, the French poured their accumulated legions into Andalusia, Cadiz alone had been preserved from the deluge. Since that time the troops of Soult had environed it in vain. Secured by a British garrison, strongly fortified by nature and well supplied from the sea, it was in little danger of capture; and it discharged, indeed, a substantial service by detaining a large detachment from the general operations of the war. In fact, the French could scarcely be described as besieging it, for, though they maintained their guard with unceasing vigilance, it was at so respectful a distance that the great mortar which now stands in St. James’ Park was cast especially for this extraordinary length of range, and their own position was intrenched with an anxiety sufficiently indicative of their anticipation. Exempted in this manner from many of the troubles of war while cooped in the narrow space of a single town, the Spanish patriots enjoyed ample liberty of political discussion, and the fermentation of spirits was proportionate to the occasion. It was here that the affairs of the war, as regarded the Spanish critics, were regulated by a popular assembly under the control of a licentious mob; and it was here that those democratic principles of government were first promulgated which in later times so intimately affected the fortunes of the Peninsular monarchies. ‘The Cortes,’ wrote Wellington, ‘have framed a Constitution very much on the principle that a painter paints a picture – viz., to be looked at. I have not met any person of any description who considers that Spain either is or can be governed by such a system.’ From this body, however, the British commander succeeded in temporarily obtaining the power he desired, and he returned to Portugal prepared to open with invigorated spirit and confidence the campaign of 1813.

Several circumstances now combined to promise a decisive turn in the operations of the war. The initiative, once taken by Wellington, had been never lost, and although he had retrogaded from Burgos, it was without any discomfiture at the hands of the enemy. The reinforcements despatched from England, though proportioned neither to the needs of the war nor the resources of the country, were considerable, and the effective strength of the army – a term which excludes the Spanish contingents – reached to full 70,000 men. On the other hand, the reverses of Napoleon in the Russian campaign had not only reduced his forces in the Peninsula, but had rendered it improbable that they could be succoured on any emergency with the same promptitude as before. Above all, Wellington himself was now unfettered in his command, for if the direction in chief of the Spanish armies brought but little direct accession of strength, it at any rate relieved him from the necessity of concerting operations with generals on whose discretion he had found it impossible to rely. These considerations, coupled with an instinctive confidence in his dispositions for the campaign, and an irresistible prestige of the success which at length awaited his patience, so inspirited the British commander that, on putting his troops once more in motion for Spain, he rose in his stirrups as the frontier was passed, and waving his hat exclaimed prophetically, ‘Farewell Portugal!’ Events soon verified the finality of this adieu, for a few short months carried the ‘Sepoy General’ in triumph to Paris.

At the commencement of the famous campaign of 1813 the material superiority still lay apparently with the French, for King Joseph disposed of a force little short of 200,000 men – a strength exceeding that of the army under Wellington’s command- even if all denominations of troops are included in the calculation. But the British general reasonably concluded that he had by this time experienced the worst of what the enemy could do. He knew that the difficulties of subsistence, no less than the jealousies of the several commanders, would render any large or permanent concentration impossible, and he had satisfactorily measured the power of his own army against any likely to be brought into the field against him. He confidently calculated, therefore, on making an end of the war; his troops were in the highest spirits, and the lessons of the retreat from Burgos had been turned to seasonable advantage. In comparison with his previous restrictions all might now be said to be in his own hands, and the result of the change was soon made conclusively manifest.