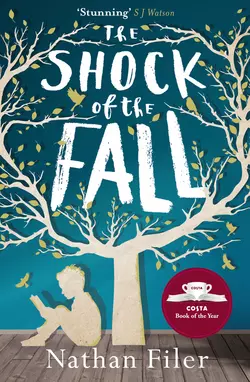

The Shock of the Fall

Nathan Filer

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: WINNER OF THE COSTA BOOK OF THE YEAR 2013WINNER OF THE SPECSAVERS POPULAR FICTION BOOK OF THE YEAR 2014WINNER OF THE BETTY TRASK PRIZE 2014It is recommended readers use the Publisher′s Fonts as they are crucial to the storytelling.‘I’ll tell you what happened because it will be a good way to introduce my brother. His name’s Simon. I think you’re going to like him. I really do. But in a couple of pages he’ll be dead. And he was never the same after that.’There are books you can’t stop reading, which keep you up all night.There are books which let us into the hidden parts of life and make them vividly real.There are books which, because of the sheer skill with which every word is chosen, linger in your mind for days.The Shock of the Fall is all of these books.The Shock of the Fall is an extraordinary portrait of one man’s descent into mental illness. It is a brave and groundbreaking novel from one of the most exciting new voices in fiction.