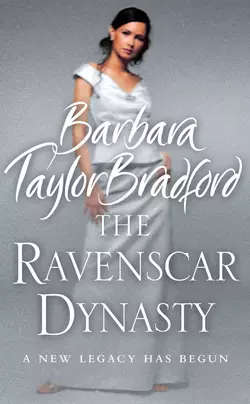

The Ravenscar Dynasty

Barbara Taylor Bradford

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 619.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The Ravenscar Dynasty, introducing the house of DeRavenel, launches Barbara Taylor Bradford’s epic new series spanning a century.Ravenscar: A house, a legacy and a dynasty.On a bitterly cold day in 1904, the DeRavenel family′s future changes for ever. When Cecily DeRavenel tells her 18-year-old son Edward of the death of his father, brother and cousins in a fire, a part of him dies as well.Edward is comforted by his cousin Neville Watkins, who is suspicious of the deaths. The two men vow to seek the truth, avenge the deaths and take control of the business empire usurped from Edward′s great uncle sixty years before. And so begins an epic saga about an astonishing family, set in extraordinary times.Handsome, charismatic and a notorious womaniser, Edward battles his cousin, Henry Grant, for control of the family empire. Elizabeth Wyland, a young widow and a great beauty, stands by his side, and they are secretly married. She is power hungry, and ambitious. But Edward also has a mistress: Jane Shaw, a constant in his life. And as Elizabeth′s jealousy damages their marriage, Edward′s only solace is his work and Jane.Edward′s position as the glamorous head of the DeRavenels is fatally rocked when betrayal comes from within. Soon, catastrophe threatens to destroy the family and the business…Power and money, passion and adultery, ambition and treachery – all illuminate a dramatic saga set against the backdrop of the Edwardian Era and the Belle Epoque, just before the First World War.