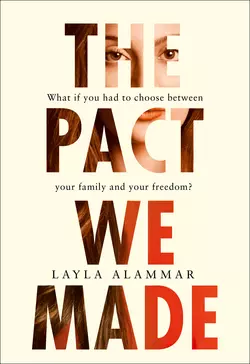

The Pact We Made

Layla AlAmmar

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1396.59 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: What if you had to choose between your family and your freedom?.‘How could I explain to her that nothing in my life felt real? That in a country like Kuwait, where everyone knew everything about each other, the most monumental thing to ever happen to me was buried and covered over? For the sake of my reputation, my future, my sister’s and cousins; the family honor sat on my little shoulders, so no-one could ever know.’Dahlia has two lives. In one, she is a young woman with a good job, great friends and a busy social life. In the other, she is an unmarried daughter living at home, struggling with a burgeoning anxiety disorder and a deeply buried secret: a violent betrayal too shameful to speak of.With her thirtieth birthday fast-approaching, pressure from her mother to accept a marriage proposal begins to strain the family. As her two lives start to collide and fracture, all Dahlia can think of is escape: something that seems impossible when she can’t even leave the country without her father’s consent.But what if Dahlia does have a choice? What if all she needs is the courage to make it?Set in contemporary Kuwait, The Pact We Made is a deeply affecting and timely debut about family, secrets and one woman’s search for a different life.