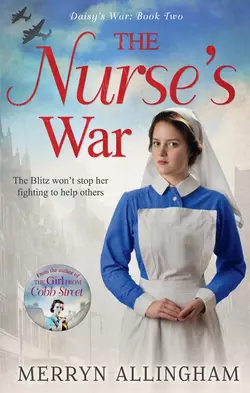

The Nurse′s War

Merryn Allingham

Working round the clock for her country1941: As a nurse in the rubble-strewn East end of London, Daisy Driscoll is a first-hand witness to the trauma of the Second World War. All she can do during the Blitz is to protect herself – and do her best to help others survive.The cacophony of guns and bombs assailing the dark empty streets of London are now the soundtrack to her life. Yet this isn’t the only war Daisy is fighting – there’s a battlefield in her heart as she deals with her husband’s cruel betrayal. As Daisy tries to forge a new life without him, she is determined not to become dependent on another man – but first she must face her very deepest fears…The Nurse's War is the unforgettable sequel to The Girl from Cobb Street by Merryn Allingham.A heart-warming story for fans of Katie Flynn, Kitty Neale and Nadine Dorries.The Daisy’s War trilogy:The Girl from Cobb Street – Book 1The Nurse’s War – Book 2Daisy’s Long Road Home – Book 3Each story in the Daisy’s War series can be read and enjoyed as a standalone story – or as part of this compelling trilogy charting the fortunes of Daisy Driscoll.

MERRYN ALLINGHAM was born into an army family and spent her childhood on the move. Unsurprisingly, it gave her itchy feet and in her twenties she escaped from an unloved secretarial career to work as cabin crew and see the world. The arrival of marriage, children and cats meant a more settled life in the south of England, where she’s lived ever since. It also gave her the opportunity to go back to ‘school’ and eventually teach at university.

Merryn has always loved books that bring the past to life, so when she began writing herself the novels had to be historical. Writing as Isabelle Goddard, she published six Regency romances. Since then, Merryn has set her books in the early twentieth century, a fascinating era that she loves researching. Daisy’s War takes place in India and wartime London during the 1930s and 1940s, and is a trilogy full of intrigue and romance.

Merryn Allingham

To my mother who, with countless other women, fought the war on the Home Front.

‘The past is the present, isn’t it? It’s the future too.’

—Eugene O’Neill, Long Day’s Journey into Night

Table of Contents

Cover (#u10e2b185-b752-5b22-a265-fbc15673f0c6)

About the Author (#u2b5204f8-bcf8-5561-b837-f5198e9207ee)

Title Page (#u98acfb7a-9e24-57c3-90c5-75ccc36c5383)

Dedication (#u06beac5f-627e-5179-99e1-768ef77452a8)

Epigraph (#u432b6c71-83cf-592c-9a3f-77bcf59b4a27)

CHAPTER 1 (#uf765c245-35bc-5616-a4ce-586791f469a3)

CHAPTER 2 (#u2dee23b2-0df4-5c36-80b6-977dc0b230e5)

CHAPTER 3 (#u37f03b6e-911e-5b3b-b446-04ead665725e)

CHAPTER 4 (#u5fa72833-394d-55fc-a8e0-2bf71d14dbc9)

CHAPTER 5 (#u692801bb-eb8e-5e16-b970-3565a6d2e737)

CHAPTER 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpage (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_46afd4ec-2ec2-5ba1-b884-3ec253a52e1c)

London, early April 1941

The footsteps were growing louder. Or at least more distinct in the darkness. Very gradually the sounds of night had fallen away and she had become conscious of the man’s step. She was in no doubt that it was a man. He had an uneven tread, as though he were limping. No, not limping, she thought, but walking uncertainly, as though he feared to give himself away. She had no idea how long he’d been following her, since it wasn’t until she was passing Middle Street that she’d become aware of him. It had been a long and exhausting day and she was almost asleep on her feet. The night shift had come on duty at six as usual, but the wards were full to capacity and she had volunteered to stay on. It meant returning to the Nurses’ Home alone, through the black pall that nightly covered the city.

At first the blackout had come as a severe shock. In an instant, the familiar had been transformed into the frighteningly unfamiliar. But after a while, like most people, she’d adapted. Now with only the slightest trace of moon to light her way, she was confident enough to walk almost blind around dim corners and through murky streets. Until, that is, she’d heard the footsteps. They were there still: left, shuffle, right, shuffle. She felt her shoulders grow tight at the sound and scolded herself for her timidity. They were in the middle of a war and she was falling into panic over a man’s footfall. After all he’d made no attempt to overtake her; in all likelihood he was an innocent, lost in a maze of unrecognisable streets and trying only to battle his way home.

For several minutes she was comforted. But then a thought struck, unbidden and unwelcome. For a stranger to lose his way in these streets would be extremely unusual. The only men she ever encountered at this time of night were there for a purpose. Patrolling wardens with their constant refrain of ‘Put out that light,’ members of the Home Guard who would flash her a greeting with their torches when they caught sight of the nurse’s uniform. This man was alone and surely it wasn’t her imagination that he walked stealthily. Whatever his intentions, she doubted they were benign. The blackout had brought its own troubles and not everyone was doing their bit for King and country.

Out of the darkness a freshness filled the evening air, the freshness of new grass. She must be approaching Charterhouse Square and thanked heaven for it. She was nearly home. In her eagerness to reach safety, she quickened her pace again. The clouds momentarily cleared and through the trees she glimpsed the outline of the Nurses’ Home, its pointed gables floating against the night sky and its large oak door standing sturdily on guard, a portcullis resisting all invaders. She was crossing the square now, fumbling in her bag; she must have her key ready for the minute she reached the door. But the man had increased his pace, too, and she was having almost to run to stay ahead. She fled across the grass, ducking between branches, brushing her way past newly budding leaves. By the time she reached the road on the far side, her heartbeat was drumming in her ears and her breath coming short. She sped across the last few yards of pavement, slowing herself as she reached the iron railings, then quickly up the whitewashed steps, the key clenched in a hand that she couldn’t quite keep steady.

The moon had once more disappeared behind a blanket of cloud and she was forced to feel for the lock. Let me get it right, let me get it right, her mind repeated frantically. The key slotted into the lock and she felt the breath escaping from her body in a sigh of relief. Then, without warning, a hand emerged from the blackness and wrestled the key from her hand. It fell uselessly to the ground, but when she opened her mouth to scream for help, another hand clamped itself to her mouth and stifled the cry.

‘Daisy. It’s me.’ The words hissed through the air.

Her attacker had said her name. But how? And whose was the voice?

‘You’re perfectly safe, but you mustn’t scream. If I take my hand away, promise you won’t.’

It could not be. It could not. She was hallucinating. He was dead. She’d seen with her own eyes his fall into the swollen river. He was dead, he was dead.

‘Promise you won’t make a sound,’ the man repeated. ‘Nod your head.’

It had to be his voice or it was that of his ghost. And she didn’t believe in ghosts. Dumbly she gave a nod and the hands released their hold. She stood not daring to move, her limbs immobile but her chest rising and falling in rapid motion. The figure beside her was searching for something. Then the sound of a match being struck and a small, solitary light flared for an instant. It was sufficient. She had not been hallucinating. The face had changed—the skin was weathered, the face bones gaunt, but it was him. It was Gerald. He had not died in that Indian river. For a moment she was overcome with a sudden nausea as the old guilt broke free of its moorings.

Somehow she managed to find her voice, hoarse and hardly recognisable. ‘Is it really you? I don’t understand.’ How ridiculous that sounded. The understatement of all time.

The memory was so vivid that every one of her senses added a layer to the image. She could still hear the shouts of her captors, feel the hot rain soaking her dress, see the raging waters closing on her husband’s head. How then could he be here? At one violent stroke, the past she had tamed had broken its bonds and was showering her with its fragments. She began to shake uncontrollably and was forced to lean against the massive door for support.

‘It’s me all right.’

‘But how …?’ The question was dredged out of her.

‘I escaped, that’s how. Pure luck.’

‘But how?’

‘My shirt snagged on one of those damned festival floats—would you believe? But it stopped me from going under. I was pulled down the river for miles—you know how fierce the water was. Then the float got pushed into the bank and lodged there.’

‘And you weren’t injured?’

‘A broken arm, that’s all, and it mended pretty quickly. People came from the village to see what had drifted their way and found me instead of the goddess they’d expected. They looked after me until I was fit to leave.’

‘You had an astonishing escape.’ How trite she sounded, but in the face of such extraordinary fortune, what more was there to say? Except there was more. The shock was slowly receding and the questions had begun.

‘But once you were well, once your arm had mended, why didn’t you go back to Jasirapur?’ Why didn’t you face the crime you committed? her inner voice accused. ‘And the—the incident—happened well over a year ago. Where have you been since then? And how did you find me?’

The moon was still in hiding and she couldn’t see his face but she could imagine the irritated expression it wore. Her questions had always annoyed him. He left most of them dangling in the air, choosing only to answer the last.

‘I used my head, Daisy, that’s how. I didn’t know if you were in London, but I thought it worth looking for you.’ What he really meant, she thought, was that he hadn’t known whether she was alive or dead, but that was something he wasn’t going to say.

‘If you had returned to London,’ he continued smoothly, ‘it was possible you’d gone back to Bridges to work. So I called at their perfume counter. You weren’t there, but I had another piece of good fortune. One of the girls you used to work with had seen you. Quite recently too. Her sister was a patient in St Bart’s for a while. She’d just had an operation and when this girl visited, she was sure she’d seen you there. She said you were wearing a nurse’s uniform. So I’ve been hanging around the hospital for a few days hoping to catch you. But no sign. I thought my luck must have run out at last. Tonight when I saw you leave, I’d almost given up.’

‘I’m not always at St Bart’s. Sometimes I have to travel to Hill End. It’s in the countryside, near St Albans. Patients are evacuated there as soon as they’re stable enough.’ She felt stupid—why was she bothering to explain? ‘But what girl at Bridges? And where are you living?’

A chilly breeze sprung out of nowhere, snaking around the corners of the square, and whipping up the edges of her cape. Across the grassed space, the leaves rustled angrily. For an instant, she felt a shadow pass across her vision and blinked in surprise. It made her shiver slightly. She was sure that Gerald had seen it, too, for he shifted uneasily from foot to foot, and his voice when he spoke held the barely contained impatience she had come to know so well.

‘We can’t talk now but I need your help. We must meet—soon—but somewhere else.’ He reached out and gripped her by the arm. It was such a fierce tug that she let out a small cry of pain.

He stepped back and his tone was more conciliatory. ‘I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to hurt but I have to see you. Here—’ and he pushed a piece of paper into her hand. ‘Send your message to this address. It’s a corner shop, one of those that sells just about everything. They’ve agreed to hold post for me.’

Even in her confused state, she found herself pondering why he couldn’t simply give her his address. It would be difficult for her to get to the shop as nursing staff were allowed only a short break during their working day. But she was given no chance to refuse.

‘Don’t let me down, Daisy. Remember, you’re still my wife.’

It was almost a threat, at best emotional blackmail, and from a man who had wronged her dreadfully. She should tell him to go away and never return, leave her to whatever peace she’d found. But old loyalties were not so easily subdued.

‘I’m not sure that I can help.’ At the very least, she must dampen his hopes.

‘You’ve got to. I’ve no one else. My parents are dead. The house they were living in is a pile of rubble, like most of the East End.’

Had what happened in India robbed him of his memory? Where was the story he’d been at pains to impress on her, that his parents had died years ago in the Somerset manor house that was their family home? Years ago, not now, not in wartime, and not in a miserable tenement in the poorest part of the city. But she wouldn’t remind him of the lies he’d told. It was too complicated.

‘I don’t know how I can help,’ she repeated. ‘I’ve no money. I’m a nurse in training and my pay is barely sufficient to buy essentials. I live board free, here in the Nurses’ Home.’

But he wasn’t listening. His own tale, his own needs, were too urgent. He grabbed hold of her arm again. ‘I’m a deserter, Daisy, that’s what it’s come down to. Do you understand what that means? I could be picked up at any time and locked up for years. Do you want to see me go to prison? I have to get away—to a neutral country where they can’t touch me. I have to have papers and you’re my only hope. Send me a message tomorrow with a time and meeting place.’

He turned to go and she was left standing helplessly on the threshhold. At the bottom of the flight of steps, he turned to face her again. ‘By the way, I’m not Gerald Mortimer any more—for obvious reasons. Send your message to Jack Minns. That’s who I’ve become.’

And who you always were, she thought. But he had gone, stealing noiselessly into the soft thickness of the night. She bent down and moved her hand over the stone step trying to locate the dropped key. At last her fingers fastened around it and, with a shaking hand, she managed to slot the key back into the lock and let herself in.

Her room was small and bare, containing nothing more than a narrow bed, a chest of drawers and a desk that had also to serve as a dressing table. But it was her room and hers alone and she was fortunate to have it. Most of the student nurses were forced to share. The Home was always a noisy and boisterous place, reverberating with laughter, with chatter, with music from radios played too loudly. Tonight someone at the end of the corridor was banging on the bathroom door in an effort to gain entrance, someone else was calling to her friend, asking to borrow a hairbrush, a girl two doors down was pleading for quiet to study. Daisy cherished the privacy of her room and this evening it was beyond the price of rubies.

The day had been disastrous. The buses had been late leaving for Hill End and thrown everything else out of kilter. Patients were still in beds they should have left hours before. And then a sudden influx of people suffering severe influenza had made the last few hours chaotic. Barts had been designated a casualty clearing station and most of the medical staff had been transferred to the country hospital. She’d felt honoured to be one of the small number who remained in London to deal with casualties and medical emergencies. But honoured or not, it was gruelling work. For most of last year, London had endured constant bombing and she had seen some terrible injuries. Legs smashed, backs full of broken glass, crushed hands and feet. Injuries that required dedicated nursing alongside the unremitting duties of every student: making beds, emptying bedpans, sluicing foul linen, rolling bandages for the dressings trolley. It was a relentless round of physical labour. And tonight, just when she’d barely been able to keep herself upright from fatigue, this blow had fallen on her. An unbelievable blow.

She threw her respirator into the corner of the room and fell on the bed, still fully dressed. She was tempted to sleep in her uniform, except she couldn’t see how she was ever to sleep that night. Supper had been missed but she hardly cared. A plate of stodgy carbohydrate was the last thing on her mind. She lay looking up at the ceiling, her eyes painfully sore, tracing every crack in the plaster, every smudge in the whitewash, round and round, up and down. Waves of shock, of disbelief, broke over her. Guilt, too, swelled and foamed in their midst. There had always been guilt. Gerald had wronged her but he had also given his life to save her.

Except that he hadn’t. He had lived, and now he was on her doorstep asking for help. She was his wife, he’d said, and she had to aid him. That angered her. She had been no wife in any sense of the word. He’d made sure of that. He hadn’t wanted to marry, had accused her of forcing his hand, and she’d been made aware of his resentment almost every one of the days she had spent with him in India. The bungalow they’d shared had become a prison. Now it suited him to remember there had been a marriage and that she owed him loyalty. But even if she agreed and was willing to help, how on earth could she? He hadn’t listened but she’d told the truth when she’d said that she had no money and no contacts. Nobody who could miraculously produce the papers that would enable him to travel to another country.

She fixed her eyes on the ceiling, following again the cracks as they traced a snaking path from one side of the room to the other. Her mind was roaming to a dangerous place, to the one man who might know how to pull strings. But she would not think of Grayson. She had trained herself not to. She wasn’t sure he could help or that he’d be willing to, and she certainly wasn’t going to ask. Gerald was a deserter and Grayson would take a very dim view of that. In any case, her friendship with him was over, decidedly over. Six months ago he’d taken his dismissal, she’d thought, almost gratefully, and moved on to a new love. No doubt he was already halfway to being married himself.

She uncurled the piece of paper Gerald had pushed into her hand. The address he’d written was a street she knew well, one deep in the East End and near her own birthplace. Near Gerald’s birthplace, too, though he had never admitted it. Until tonight when he’d spoken of his parents. But that was a slip of the tongue, she was sure, brought on by the stress of the moment, and it wouldn’t be repeated. She clambered wearily off the bed and removed her uniform, piece by piece. However distressed she felt, she had to get some sleep. The alarm was set for six o’ clock and tomorrow would be another exhausting day. It was her turn again to accompany a group of patients to St Albans. From early in the morning, the converted ambulances would be waiting in convoy outside, ready to convey to safety those casualties well enough to travel. St Barts had received several direct hits and, though no one had yet been killed, the blasts had been severe enough to blow several nurses across their ward. In comparison Hill House seemed a sanctuary.

She had been asleep barely an hour when a hammering on the door woke her. The Home Sister, Mrs Phillips, was making her way along the corridor, shouting at the nurses to come down immediately. Through the blur of sleep, she heard the unmistakable sound of the siren and in the near distance the drone of planes and the roar of guns massing in unison. Another night raid, another night spent on mattresses in the basement. She wondered why they’d ever complained about the phoney war. Until last May they’d been waiting for the bombs that never came. If only that had continued. Initially, there’d been a flurry of planning. A million burial forms had been issued, the zoo had killed its venomous snakes and London had been emptied of its children. And then the wait for something to happen. At the time it had seemed endless, but when it was finally over, she was left bewildered that they’d wished for anything else. Fifty-seven nights of continuous bombing had reduced London to a state of siege. Then out of the blue, the bombs had ceased. People had begun to relax. They’d lost their tired and haunted look, lost their red-rimmed eyes which told of fear and sleepless nights. But it hadn’t lasted and a few weeks ago, the bombardment had started anew and nerves were once more becoming stretched.

She staggered to her feet, wondering how big the raid was likely to be and whether or not she might make it back to bed that night. She had reached the door when a loud thump the other side made her jump back.

‘You clumsy idiot!’

It was the voice of Lydia Penrose and Daisy had a very good idea of the victim. She opened the door a fraction and saw Lydia picking herself up from the floor, her face an ugly red. A briefcase had disgorged its contents and books and papers lay scattered on the landing.

‘I didn’t push you,’ Willa Jenkins was assuring her colleague. ‘I think you must have caught your foot in the carpet. It’s worn into a hole back there. Look.’ And she pointed behind her to the staircase both girls had just run down.

‘So you’re saying it’s me that’s clumsy!’ Lydia barred the way aggressively, standing with hands on jutting hips. ‘That’s pretty good coming from someone who breaks everything in sight. You can’t have earned a penny since you’ve been here with all the stuff you’ve had to pay for.’

Willa stood her ground. ‘I may have broken a syringe or two, but I didn’t push you.’

‘A syringe or two!’ Lydia snorted. ‘The factory can’t keep up with you, Jenkins, and I distinctly felt your fat little hands in the small of my back.’

For once Willa was proving obstinate. She shook her head, refusing to take the blame.

‘I’m not arguing with rubbish like you,’ Lydia flung at her. ‘You can pick up everything you made me drop.’

When the girl made no move to comply, her tormentor came right up to her and shouted in her face, ‘NOW!’

Even then Willa didn’t immediately do as she’d been ordered and Daisy could see her trying to summon the courage to resist. She knew that feeling. How many times in the orphanage had she tried to fight back and failed? And it was the same for Willa. The girl’s shoulders sagged and she knelt down on the landing and obediently began to heave books and papers into the briefcase.

‘Do it neatly,’ Lydia almost screeched. ‘In the right order. In the order I had them.’

‘I don’t know what that was,’ the girl said miserably.

She was still picking up books when Sister Phillips’ head appeared over the bannister. ‘Get a move on nurses, the raid is almost on us. And that means you, too, Driscoll,’ she scolded, catching sight of Daisy in the doorway.

‘I’m coming, Sister.’ Mrs Phillips was not a woman you disobeyed lightly. She did her job dourly and any nurse who stepped out of line knew she would face a sarcasm that could wither.

But tonight Daisy was willing to risk it. When the senior nurse had disappeared down the stairs followed by her two acolytes, she crept back into her room and shut the door behind her. Tonight she could not bear to be in the company of her fellows, to share the basement’s windowless prison, to lie and listen to the sniffs, the coughs, the fidgeting limbs of a score of bodies, while she longed for forgetfulness. She would stay above ground and hope to sleep once the bombers had passed.

But not yet. The sound of approaching aircraft grew louder. A mad cacophony of guns and bombs burst through the night and assailed the dark, empty streets. With care she lifted the corner of the blackout curtain and squinted through the small square she’d uncovered. She saw immediately that it was another big raid. The sky was laced with light: the beams of searchlight batteries, the stars from bursting shells. A rainbow of colours—green, red, yellow, white—tumbled one over another in endless profusion. Coloured tracers like giant strings of beads winged their way through the sky in search of planes which had no right to be there. Planes that brought death and destruction. Whichever way she looked, from east to west, the night was aglow. Flashes from hundreds of incendiary bombs split the darkness and on the horizon dozens of fires burned, as though they were giant open air furnaces. All around Charterhouse Square, the stone of the buildings was lit with a white glare. Wearily, she let the curtain fall and climbed into bed. She would stay here and take her chances.

It was not until early afternoon that she climbed aboard one of the specially adapted Green Line buses travelling to Hill End. Last night’s raid had wreaked enormous destruction and casualties had been pouring into the hospital from the moment she’d walked on to the ward at seven that morning. As civil defence teams continued to dig people from the rubble, a trickle became a stream and, very quickly, a river. Medical staff had been working through the night and Daisy and her new shift were met by nurses and doctors near to collapse. The official handover was brief; time was short and they could barely hear each other above the jangle of ambulance bells and the sobs of hurt and shocked people. She was set to work immediately, bathing newly admitted casualties, a lengthy business since the wounded were covered from head to foot in brick dust and blood. The nurses worked tirelessly and at great speed, their aprons bloodstained, their young faces marked by fatigue. There was no time to eat. A snatched slice of bread and dripping and a large mug of tea were all Daisy managed before the ward sister called her over.

‘You should go, Driscoll. The escort party is waiting and we can spare you now. The ward is running well.’ Sister Elton gave the glimmer of a smile. It was the nearest she would ever get to giving praise.

Daisy made her way down the two flights of stairs to the street. Her head was aching and her legs hardly felt her own, but there was no possibility of rest. There was always more work to do. A nurse helping to load patients into one of the makeshift ambulances scrambled down to greet her.

‘Where did you get to last night?’ As she spoke, the girl tried unsuccessfully to tuck the straggling ends of her bright red hair into the starched cap.

‘I’m sorry I missed you, Connie, but I worked on. Sister needed extra help and by the time I got back, I was too tired even to speak and went straight to bed. I didn’t even make it to the basement.’

Connie Telford was her closest friend. Their rooms were next door to each other and in the last few months they’d often been rostered to work on the same ward. It was rare for them to miss an evening drink together, but Daisy had been too shocked last night to go in search of her friend and certainly in no mood to exchange confidences.

‘I can’t see us getting this lot settled before midnight.’ Her friend gestured to the line of buses waiting to leave. ‘Looks like we’ll be taking our cocoa at Hill End tonight.’

Daisy smiled a little wanly. If only cocoa was her sole concern. Today had been so hectic that even the reappearance of Gerald in her life had been pushed from her mind. But now he’d returned and was looming large. She would have to sleep at Hill End and would not be back in London until the following morning. There would be no opportunity to send the message he’d demanded. Perhaps if she didn’t respond, he would go away and leave her in peace. If only he would. She could see he was in a dreadful predicament, but there was no way she could help, and meeting him was pointless. All it would achieve would be to bring back the terror and grief of those last days in Jasirapur. It already had, she thought angrily. He demanded loyalty as his right, yet he’d explained nothing. How had he reached England, how had he travelled those thousands of miles alone and without money or support? His rescue by the villagers she could just about understand, but even that was extraordinary. The power of the water had been immense. Had she not faced it herself, standing on that riverbank, ready for the blow that would send her to her death? It was Grayson who’d arrived to rescue her, but too late to save her husband.

Yet somehow Gerald had survived. Survived to be a deserter. He hadn’t returned to his regiment in Jasirapur, hadn’t confessed his wrongdoing. Instead he’d gone into hiding. But he’d be discovered sooner or later, that was certain, so why did he not give himself up and face just punishment? Running and hiding could only be done for so long. And it was cowardly. She, and everyone she knew, was working tirelessly for their country, fighting for its very existence. Should she really be helping a man—husband or not—to abandon his homeland and make a bolt to safety?

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_d7eb8d42-ccb7-506d-9245-121be503465d)

Today the journey to Hill End seemed longer than ever and, once they’d arrived, there were hours of work ahead of them. For the rest of the day while her hands bandaged, soothed, gave medicine and spooned food, Daisy’s mind was elsewhere, circling the same questions, but unable to find a solution. By ten o’clock that evening, the ward was calm and the night staff could be left to manage alone. The ward sister who had accompanied them from Barts shooed her nurses off to bed. At least there was no Mrs Phillips here to monitor the food they were eating or check that bedroom lights were out by ten-thirty. Daisy usually enjoyed the break from the inflexible set of rules at Barts. Nursing in London was a constant challenge and a source of adrenaline, which could buoy her on the most fatiguing of days. But at times its iron conventions made her yearn for a less rigid regime. No chattering, no sitting on beds, no eating—not even a single precious sweet from a patient. And one’s uniform had always to be immaculate: dress uncreased, pinafore starched and without a single lock escaping the small cap. It was no wonder that Connie fought a losing battle with her tumble of thick red hair and was constantly in trouble.

She came bustling up at that moment and grabbed Daisy’s hand, dragging her into the sitting room used by the permanent staff at Hill End. A few nurses were lolling in one or two of the shabby chairs dotted around the room, or flicking idly through a pile of dog-eared magazines while they carried on a desultory conversation. Her friend steered her into the quietest corner.

‘Now, Driscoll, what’s up?’ Hazy green eyes, wide with curiosity, fixed her to the spot.

‘Nothing, nothing at all.’ She did her best to look unconcerned.

‘That’s rubbish. Something is definitely wrong. I’ve been watching you since we got here and you’re not yourself. Now tell me what’s happened.’

Daisy reached up and unpinned her cap, shaking out the dark waves as though to free herself of constraint. She stabbed a hatpin through the starched white material. ‘I can’t,’ she said at length. ‘It’s too complicated.’

‘Don’t I know that? Everything to do with you is complicated. Whereas me, I’m an open book.’

Connie’s grin elicited a smile. Daisy could never feel downhearted when she was with her. The girl was chockfull of cheerful common sense and practical to her fingertips. She’d had to be, of course. As the eldest sibling in a crowded Dorset cottage, she’d borne the brunt of her mother’s frequent pregnancies and her father’s forbidding temper. Her sweet nature, though, had gone unvalued and, despite a large family, she appeared to be as lonely as Daisy. It was telling that she’d chosen not to train in Dorchester but to move miles away to the big city. It was probably that solitariness, Daisy mused, that had drawn them together in the first place. But by now they’d become the firmest of friends, confidantes in the daily struggle of nursing through a war.

‘It’s complicated because it doesn’t just concern me.’

‘So who else? Who else do you know?’

Her friend wasn’t giving up, it seemed, and she longed to confide in her. It would be good to share the burden, but it would also be grossly unfair. Gerald had committed a crime and she must be careful not implicate Connie by confessing the trouble she was in.

She felt her hand squeezed and her friend’s voice, low and encouraging. ‘You know that whatever you tell me, I can keep my mouth shut. Who is worrying you so badly?’

Perhaps if she said only a little? She’d already told Connie more than she’d ever thought possible, and months ago had abandoned her ingrained reserve to confide that she’d once been married. Connie was the only one she’d ever told about Gerald.

She took a deep breath and met her friend’s eyes. ‘It’s my husband.’

The girl’s mouth fell open and it was a while before she could speak. ‘But he’s dead.’

‘That’s the problem. It turns out that he isn’t. And he’s managed to trace me—it doesn’t matter how—but he followed me back to the Home last night. I think I’m still in shock.’

‘But how can it be him?’ Connie was floundering. ‘You saw him drown.’ The phrase was blunt and to the point. And it was true, she had seen him drown, or so she’d always thought.

‘He didn’t. His clothes were caught up on one of the floats. You remember, I told you we were at a festival called Teej and there were all these stupendous floats with huge gods and goddesses that were launched into the river. I guess most of them were smashed to pieces when the monsoon broke—the river turned into this raging torrent—but there was enough left of one apparently for Gerald to catch hold of and survive. He was rescued further downstream.’

‘And then?’ Her companion edged forward.

‘I have no idea. How he got to England is a mystery.’

Connie gave a soft whoop. ‘That’s quite a story. Romantic too. Your husband has travelled thousands of miles to claim his wife. You told me things were bad between you before he died, but maybe this is a turning point.’

‘Unlikely. He’s come back because he has nowhere else to go. And he’s come to me only because he needs help. But there’s no way I can help him, and he won’t believe me.’

Her friend wrinkled her forehead, the freckles almost joining each other in puzzlement. ‘What kind of help does he want?’

She took some time to answer, weighing up how much she should say, how much she dare tell even a close friend. It would not make a good hearing and it might make a dangerous one. But Connie was right when she said she could keep her mouth shut. It was a quality that was necessary, Daisy guessed, living amid a large, raucous family.

‘I’ve never said anything before,’ she said slowly, ‘but Gerald was involved in some wicked things in India. He died trying to rescue me from a dangerous gang.’ She saw Connie’s bewildered expression. ‘I told you it was complicated.’

‘A dangerous gang? What on earth did you get yourself involved in?’

‘I made a discovery that I shouldn’t have. Something that could have hung every member of the gang. And they knew I knew, so I had to die.’

‘My God, Daisy!’

‘Gerald found the place they were holding me. He put up a fight and that messed up their plans. It gave the police sufficient time to get to me.’

‘It might not be exactly romantic but—’

‘He wasn’t innocent,’ Daisy said quickly. ‘His association with the gang was what put me in danger.’ She wasn’t going to mention the ‘accidents’ that Gerald had been happy to agree to, accidents that had been meant to frighten her away but hadn’t.

‘In the end he did the decent thing, I know.’ She tried to sound grateful. ‘And he paid a price for it. Not death as it’s turned out, but as good as, I guess.’

Connie’s mind was still in the past. ‘What happened to the gang?’

‘They went to prison and they’re still there. They must believe they drowned Gerald. But his regiment thought he’d died trying to rescue me. The army had no idea of the real situation and they still don’t. He never went back to Jasirapur once he’d recovered from his injuries. If he had, the Indian Army would almost certainly have court-martialled him and then turned him over to the civilian courts. Anish warned me he could face criminal charges, as well as disgrace.’

‘I’m sorry for all these questions, but who is Anish?’

‘It doesn’t matter.’ She couldn’t bring herself to talk about the man who had masterminded her downfall, yet for whom she was still grieving. ‘The point is that Gerald is a deserter who wants my help, and I don’t know what to do.’

Connie shook her head. ‘You can’t turn him in, that’s for sure. Whatever he’s done, he’s still your husband. Could you persuade him to give himself up?’

‘I doubt it. Gerald is someone who first and foremost looks after his own interests. In this case it’s keeping out of prison. He wants to leave England and travel to a neutral country where he’ll be safe.’

‘And you’re going to help him?’ Her friend had the ghost of a smile on her lips.

‘Exactly. It’s stupid. There’s no way I can. I’ve no money and I know nobody who could get the papers he needs.’

Connie was thoughtful. ‘But if you could get those papers, it would mean you’d lose him from your life once and for all. I know you think you’ve put the whole Indian thing behind you, Daisy, but it’s clear that you haven’t. Until tonight I didn’t know how awful it had been for you, though I knew something pretty bad had happened. You never talk about the past. Whenever I’ve touched on India or your husband, you’ve brushed it off as though your time there wasn’t worth mentioning. It’s obvious, though, that it still looms large.’

It did and she couldn’t deny it. The frightening months she’d spent in Jasirapur when she’d suffered one so-called accident after another, only to discover that it was her husband behind them. And then to find that her dear friend, Anish, was the ultimate puppet master. The grief at losing him; the guilt at not grieving for Gerald. It had all been too much and she had shut her mind fast. The past could be locked up in a box and the key thrown away. That’s how she’d thought about her time in India. That’s why she’d been unable to be anything but a poor friend to Grayson. He was too involved in the whole business; he was a constant reminder of what she had to forget.

‘What about Grayson Harte?’ her companion asked out of the blue. It was almost as though Connie had read her mind. ‘Isn’t he in the Secret Intelligence Service? Surely he could manufacture false papers. That’s what they do, isn’t it?’

‘No.’ Her response was unequivocal.

‘What do you mean “no”—I think it’s a brilliant idea.’

‘I don’t see Grayson any more. You know that.’

‘But you could. You know where he works. What’s to stop you visiting him?’

‘So I just turn up at his Baker Street office and say, Sorry, Grayson, that I wasn’t able to return your feelings. But actually you can do me a favour. Gerald didn’t die after all, can you believe that? He’s back in England and living in London. He’s a deserter, of course, and I need your help to get him out of the country.’

‘Okay, I understand. I know it won’t be easy.’

‘Not easy! It’s impossible. And I refuse even to think about it.’ She uncurled herself from the lumpy chair and walked to the door, unable to stifle the first of many yawns. ‘I’m so tired, Connie, I don’t think I can even find my way to bed.’

‘You will,’ her friend promised, ‘and you’ll sleep. And tomorrow you could feel quite differently.’

But she didn’t feel differently; when back in London the next evening she walked quietly through the darkened streets. This time she was careful to leave the hospital with other nurses who had come off duty at the same time. After the encounter with Gerald, she was taking no chances, but the only footsteps she heard were those of her companions and they reached Charterhouse Square without incident. At the huge oak door, she waited patiently while the girl in the lead fished around in her bag for a key. Tonight the darkness seemed more impenetrable than ever, not even a glimpse of moon or stars. Several seconds of fumbling produced the key and Daisy mounted the steps behind her companions. As she turned to walk through the door, she glimpsed a shadow pass between the square’s trees. Or so she thought. She couldn’t be entirely sure, but her eyes had slowly grown accustomed to the intense gloom and what she’d seen was definitely a form that was blacker than the rest. And it was a form that was moving. Could it be the figure of a man and that figure, Gerald? She’d had no time to send the note he’d insisted on, so had he come to check on her, to harangue her on where her duty lay? It was more than likely.

She walked into the tiled entrance hall and stood still, aware of her pulse having gone into overdrive. She was becoming stupidly panicked and she must stop herself from seeing things that were probably not there. Given the heightened state in which she’d been living these last two days, it was unsurprising her mind was all over the place. It wasn’t fear of bombing raids that disturbed her—that was a fear everyone shared. It wasn’t even the unremitting labour. There were nurses who worked harder. It was alarm at finding her husband alive, and not just alive, but close by and demanding her aid.

She passed the staff pigeonholes with hardly a glance. There were never letters for her. Tonight, though, something white glared balefully from the scratched wooden box. An envelope addressed to her. She recognised the writing straight away. So it had been Gerald lurking in the trees, watching for her, waiting to accost her. But why hadn’t he done so? Instead, he’d pushed the missive through the letter box and someone had picked it up and put it in her pigeonhole. She took the envelope and held it up to the dim light which dangled from the ceiling. Now that she looked closely, she saw the letter had not been hand delivered at all but had come through the mail. It was postmarked ten a.m. It had come in the morning post and been waiting for her all day. So the shadow she’d seen … it couldn’t have been Gerald. But if it wasn’t, who was it?

Her heart again began to beat far too rapidly, sounding heavy in her ears. She tried to calm herself by visualising what she’d seen. It must have been imagination. But the more she thought of it, the more certain she became that there had been a figure there. It wasn’t just panic talking. She recalled the blurred image and fixed her mind doggedly on it. It reminded her of another shadow she’d glimpsed recently, one that had passed like a ripple through those self-same trees the night before last, when Gerald had stopped her on the front steps. Had someone been watching them then? Was someone watching her now? Or was that someone looking for Gerald, looking perhaps to find and hand over a deserter? She shook her head. It was better to think it merely the wind in the trees.

Gerald’s note was brief and to the point. She hadn’t named a meeting place, he accused, so he would: HydePark, the eastern edge of the Serpentine. Tomorrow at two o’clock. Didn’t he realise that she was a working woman, a nurse who had barely a day to herself every month? She felt exasperation riding tandem with misgiving. Meeting him was the last thing she wanted, but she would have to go or she’d have him knocking on the door. Whether or not she could take her free time would depend on what was happening on the ward. She would have to petition Sister Elton first thing in the morning and hope for permission. She calculated that she could just about make it to the park and be back on the ward within two hours, which was the most she could count on. But what she was to say to Gerald, she had no idea.

She still had no idea the following afternoon when she walked into Hyde Park. Speakers’ Corner was unusually crowded for a weekday, despite the lack of any orator and soapbox. A rare burst of spring sunshine must have tempted the mill of people. Daisy wound her way through the crowd as quickly as she could, negotiating a host of children and their nannies and a small group of women on their lunch break, enjoying a cigarette. The military post on her left was quiet and soldiers stood chatting to members of the Home Guard. A heavy anti-aircraft battery had been set up nearby along with a number of rocket projectors. She’d been told they fired six foot shells packed with metal debris—broken bike chains, old razor blades—just about anything that could be loosed skywards and disrupt the flight of bombers swooping up river from the docks to the West End.

Today, though, there was so little activity you could almost forget the guns’ incongruous presence in this beautiful, green space. The false sense of tranquillity was increased by dozens of barrage balloons which floated serenely five thousand feet above her head. They were supposed to force enemy aircraft to a height where aiming their bombs would be difficult, but the ‘blimps’, as they’d been nicknamed, had so far proved ineffective. Their silvery presence, though, added a dreamlike quality to the scene.

She reached the path leading to the Serpentine and felt inside her cape for the watch pinned to her bib. She wasn’t at all sure that she would make Gerald’s deadline, though so far luck had favoured her. She hadn’t had to ask for time off. Sister Elton had noticed how pale her nurse was looking and insisted, during the rushed morning tea break, that Daisy take several hours away from the ward once lunch had been served and the medicine trolley had done its rounds. Then, as she’d left the hospital, one of the few doctors who ran a car had offered her a lift as far as Oxford Street. Connie was on a short break, too, and off to sit in the cathedral gardens at St Paul’s. She saw Daisy getting into the car and pulled her mouth down as if to say, I told you so. It was her friend’s running joke that Dr Lawson had a particular fondness for Daisy.

If he had, she certainly wasn’t going to play on it. Work filled her entire life and that was fine. She was simply grateful for the lift. Even so, she was having to walk fast, winding her way on and off the path and around the trenches that had changed the face of all the London parks. By the time she reached the lake, she was breathless. Once more she flicked her watch face upwards. A minute to two. She’d made it, but not before Gerald. He was marching up and down beside the still water, his shoulders hunched and a frown darkening his face.

‘I thought you weren’t coming,’ was his greeting. ‘You didn’t contact me—you said you would.’

‘I couldn’t.’ She forced herself to remain calm despite his blustering. ‘I’ve been out of London for several days and it was last night before I collected your note.’

‘Now you are here, we shouldn’t waste time.’

She was taken aback by his abrasiveness, but why should she be? It was something she had grown used to in the few months they’d spent together. Now, though, she wasn’t the same girl who had travelled to India to marry him, a naïve innocent who’d foolishly believed herself loved. Her emotions had been put through fire, and she’d emerged with a new, tempered edge. If they were going to talk, she wanted some answers.

‘Shall we sit down?’

She gestured to one of the deckchairs lined up around the lake. In the first few months of the war, the chairs had been whisked from sight, but popular protest had succeeded in getting them reinstated. He didn’t immediately sit, but instead scanned the park for some minutes, turning his head in a complete circle. Then, seemingly reassured, he slumped heavily into the nearest seat and swivelled to face her.

‘Well? What’s the plan?’

‘I have some questions.’

He screwed up his face in an expression of deep frustration. ‘While you’re asking questions, I’m falling into ever greater danger. You don’t seem to appreciate that.’

‘If I’m to help, I need to know what’s happened since the last time I saw you.’

That was mendacious. No matter how much he told her, she was unlikely to be able to help. But she deserved to know how this ghost husband had come back to her from the dead, and she was willing to wait while he found the words. He was staring straight ahead, his face fixed and giving no sign that he was willing to talk. From the corner of her eye, she noticed a small boy arrive on the other side of the lake. He was cradling a boat in his arms and bouncing excitedly up and down beside his mother. He was about to sail a new toy, she thought, and that was a big event in this time of austerity.

‘I’ve already told you all you need to know,’ Gerald said at last, his tone grudging. ‘I was saved from drowning, broke an arm and a few ribs, was patched up by a local wise woman and sent on my way.’

‘And the villagers never asked where you’d come from?’

‘I made up a story.’ Of course, he would have. ‘I said I was a businessman—said my name was Jack Minns and I was trading in rapeseed. There’s plenty of that around Jasirapur and they didn’t question my account.’

She considered how credible that might sound. Gerald had not been in uniform, she remembered. He would not have had any form of identity on him. His story would be the only one in town.

‘But how did they think you’d ended up in the river?’

‘That was easy to explain. The celebrations got a bit boisterous. They always do, don’t they? And somehow I tripped and fell, and my friends weren’t able to reach me because the river was flowing too fiercely.’

‘Then surely they would have sent to Jasirapur for someone to come and collect you.’

He shook his head. She noticed a crafty smile playing around his lips. ‘I told them the friends I’d been with were also traders and by now they would have moved on, travelling north-westwards. That was the direction I intended going, towards the Persian border. I told them that once I was on my feet again, I’d start out and join them. And I did. Not join them, of course, because they didn’t exist, but I travelled north-west to the border.’

‘Without money?’

‘There are ways. The villagers sent me off with a few rupees and India is full of temples.’

‘You begged your way to the border!’

‘More or less.’

‘And after that, when you got to Persia?’

‘I scrounged whatever I could, then when I reached Turkey, took whatever job I could get. Anything that would feed me. Once I had sufficient money, I travelled on to the next place. It was bloody awful, I can tell you. The things I had to do … but once I reached France, life improved. I travelled up the country as far as Rouen and got taken on as a waiter in a local bistro. The tips were good and I actually enjoyed the life—not waiting, of course. Being at everyone’s beck and call didn’t suit me at all. But the idea of running a restaurant, that really appealed and still does. When I get to the States, that’s what I’ll do. It’s America I want to go to.’

She had been listening to him in disbelief. How much credence should she give to this account of his travels? Could she really imagine the arrogant young cavalry officer she’d known begging at temples, or scavenging food bins or waiting on tables? Or was that as much a fantasy as his plan to open a restaurant in America without money and without papers?

She said none of this. Instead, she asked, ‘If you liked the life in France so much, why didn’t you stay?’

‘Ever heard of Hitler? That’s why, Daisy. The Jerries were about to invade and it wasn’t safe. I’d picked up a bit of French here and there, but any German soldier with the slightest ear would know I was English. If they found me, I’d have been interned immediately. I reckoned I might as well languish in prison here as there.’

He saw her surprised expression. ‘Not that I’ve any intention of languishing anywhere, but I did need to get to England pretty damn quick.’

‘And you did.’

‘I met a chap at the restaurant. He used to eat there pretty regularly. He was English but had been living in Rouen for years. For a while he’d been holding his breath over the political situation, but once the Germans invaded Poland, we both knew the game was up. France as well as Britain declared war two days later and it was only a matter of time before the Germans arrived. The bloke decided to make a bolt for it back to England. Fortunately, he owned a car and I travelled back with him.’

‘I see.’

She didn’t really. She couldn’t understand how Gerald had managed to get past border controls without a passport or any form of identification. But in wartime everything was in flux and he must have looked and sounded the English gentleman. She imagined he’d told them some sad story and got them to believe it.

‘So where are you living?’

Her question was deliberately bland. When he’d appeared on her doorstep the night before last, he had let slip that he’d looked for his parents in the East End, but he was not about to confess the layers of mistruth he’d been spinning ever since she’d known him. And now his mother and father were gone, wiped out by a German bomb, there seemed little point in raking up old lies.

‘The East End,’ he said awkwardly. ‘Whitechapel.’

She remembered the address he’d given her, a shop in Gower’s Lane. She knew the road and it struck her that it was only a stone’s throw from Spitalfields, where they’d both been born. He misinterpreted her silence and said defensively, ‘I’ve hardly any money and it was the cheapest lodging I could find.’

She was still thinking. She had a very small sum saved. Should she offer it to him, or was that ridiculous? It was nowhere near enough to purchase a berth on a ship to New York. And that was without reckoning on those all-important papers. Even more important in America, she imagined, since the country was not at war and would police its borders rigorously.

‘Is the interrogation officially over?’

He smiled across at her and for an instant she glimpsed the old Gerald, the man with whom she had fallen so deeply in love. Or thought she had. His fair hair gleamed bright in the spring sunshine and though his cheeks were emaciated and his frame thin, he could almost be the same handsome man.

‘I’m sorry if it sounded like an interrogation. I didn’t mean it to be. But so much has happened to both of us since …’

She saw a quick flush mount to his face. ‘I gather Grayson Harte rode to your rescue.’ So far he’d said nothing about that terrible night, but that was not surprising.

‘So you know what happened?’

‘The tale spread like wildfire. Tales always do in India. The village was naturally desperate to hear the gossip from up river and siezed on anyone who’d been in Jasirapur. But the story they got was only half a one. I gathered from their talk that the gang had been apprehended and put in jail awaiting trial, but I heard nothing about you. I had no idea if Harte and his minions turned up in time.’

‘As you see, they did.’

There was a cold silence as they sat staring across the lake, small ripples now disturbing its surface. A stiff breeze had begun to blow and the little red painted boat was bobbing precariously away on the waves. The small boy started to cry.

Gerald shifted irritably in his seat. ‘So—what’s your plan?’ he repeated.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_7226fff7-6de4-5f7e-b43e-e5c0584ff90f)

‘I don’t have one.’

Apparently they’d said all they were going to say about the terrifying event they had shared. India was to be a closed subject between them.

‘What do you mean, you don’t have one?’

‘I told you, Gerald, I have no idea how I can help you.’

‘Jack,’ he interrupted her.

‘Jack,’ she repeated, though the sound of the name stuck on her tongue. ‘I’ve very little money but you’re welcome to what I have. I doubt, though, it will get you much further than Southampton. And as for the papers, how am I to get them?’

‘You’re a nurse. You have patients.’

‘What has that to do with anything?’

‘Patients are always grateful to their nurses and some of them must have influence. Surely you can use that.’

‘I work at St Barts, in the City.’

‘A City man then. Perfect.’

‘The City men, as you call them, go home to the suburbs at night. They have transport and money to escape the raids. It’s the East End that suffers—you must know that—you’re living there. Its people are our patients, people from small terraced houses, from crowded tenements, people with very little and even less when the bombers have finished. They’re grateful certainly, but influential, no.’

‘You’ve changed, you know. You’ve become a hard woman.’

‘Because I can’t help you? You’re being foolish.’ She looked away from him. ‘If I have changed,’ she said slowly, ‘it can only be a good thing. At least for me. It means that for the first time in my life, I’m strong enough to defend myself.’

He had the grace to look uncomfortable, but it didn’t stop him from worrying at her.

‘Grayson Harte was never a district officer in India, was he? I knew from the first he was an imposter. I told you so, didn’t I?’

She said nothing, wondering why he should alight on Grayson’s name again. She wasn’t left in ignorance long.

‘I’ve been thinking.’ He stretched his long legs and relaxed back into the canvas sling. ‘The district officer role was just a blind. Harte was in Secret Intelligence, wasn’t he? Most of those beggars are working in London now, I’ll be bound. Harte may have had to stay in India for the gang’s trial, but he can’t be there still. He’s almost certainly close by and if we’re talking influence, who better than an SIS officer to help me?’

She swallowed hard. It was exactly what Connie had said, but she hadn’t wanted to listen to her and she didn’t want to listen to Gerald either. Contriving a meeting with Grayson was the last thing she’d expected to do, and the last thing she wanted.

‘Nothing to say? Harte always had a soft spot for you. Sweet on you, I thought at the time. And he proved your white knight in the end, didn’t he?’

There was a new bitterness to his voice. Even now, she thought guiltily, even now that she had Gerald beside her, flesh and blood and alive, she hadn’t thanked him for his final act of heroism in trying to save her life. She should do it, but she couldn’t. She couldn’t bring herself to utter the words. Her sense of betrayal was just too great.

‘Who better to get me my papers?’ he taunted.

‘I don’t see Grayson.’

‘Now, I find that remarkable.’ He gave a smirk. ‘I thought he’d be a regular at the Nurses’ Home.’ She could have hit him but instead clenched her fists tightly. He looked down at her hands and the smirk grew. ‘What’s the matter? Didn’t it work out between you? That’s sad. But then comfort yourself with the thought that it wouldn’t have worked out anyway. You have a husband alive and Grayson is far too much of a gentleman to steal another man’s wife.’

‘I don’t see him,’ she repeated heavily.

‘But you could. If you chose.’ He leant over and took her hand. His touch was far gentler than she expected. Rhythmically, he stroked her forearm. She would have said it was a loving touch if she hadn’t known better. ‘And you could choose, Daisy.’

‘I haven’t seen Grayson Harte for months. We’ve gone our own ways.’

‘I’m sure you know where he works though.’ She didn’t answer and he took her silence as confirmation. ‘You could pay him a visit. Call on him for old times’ sake. Don’t mince your words—tell him your husband has reappeared and is an embarrassment, an embarrassment you’d like to get rid of. I’m sure he’ll find a way of obliging.’

‘I can’t turn up out of nowhere and demand papers for you. He’ll want to know why you’re here, how you got here. He’ll know you’ve deserted. What if he decides to turn you in?’

‘Dear Daisy, he won’t. Because, if he did, you would be implicated. You would be the wife of a deserter. Think how your nursing colleagues would react to that little piece of news, think what the hospital might do. About your job, for instance.’

‘You’re threatening my job?’

‘Not threatening, merely pointing out the salient facts—as a friend, of course. You really would be best to keep my unfortunate situation as quiet as possible, and Mr Harte will appreciate how necessary that is. He’s a master of discretion, I’m sure.’

She was caught. She could feel the underlying menace in every one of his words. If he didn’t get papers, didn’t get money and a way out of England, he wouldn’t go quietly. If he were taken into custody, he would shout his story to the sky and it would spread like a fungus, inching its diseased path into every crevice of her life. Including her workplace. And the job she loved would be in ashes, another dream destroyed.

‘If I go to him and he refuses to help—even if he doesn’t inform the authorities you’re in London—will you leave me alone?’

‘He can’t refuse.’ Gerald’s tone was adamant. ‘He has to help. My situation is desperate. Spies are his forte, aren’t they, and I’m surrounded by them. I have to get out now.’

Her eyes widened. ‘Surrounded by spies?’

‘Yes, spies. I’m almost certain of it.’ She recalled the anxious scanning of the park before he’d consented to sit down. It seemed he believed what he was saying. ‘There’s something odd about the two men who rent the room below me. For a start they’re both Indians. Well, one is Indian, the other’s Anglo. I met the Indian chap on the landing one day and he said he was a soldier. I saw his cap, it had the badge of the Pioneer Corps pinned to it, so I reckon he was telling the truth. But why isn’t he with his regiment? And if he’s left the army, why hasn’t he returned to India? There has to be something going on, some reason they’re hanging around. They’re watching me, I’m sure. They must know I’ve deserted.’

‘How can they know?’ The claim seemed utterly absurd and she wondered if Gerald’s ordeal had affected his mind as well as his body.

‘If they don’t actually know, they suspect. Think about it. I’m an able-bodied man of twenty-eight, yet I’m not with any of the Services and I’m not engaged in essential war work.’

‘And are they? They might be deserters too.’

He shook his head. ‘Deserters from what? The character from the Pioneers has a limp, so he’s unfit to fight. I know his unit was brought over from the Punjab to work on demolition. Clearing derelict buildings, that sort of thing. Some of them were skilled engineers. They’d need to be, using dynamite. He might have been one of them and suffered an accident. But that doesn’t explain why he hasn’t been put on a boat back to India. He’s not British and he shouldn’t be here.’

‘And the other man, the Anglo-Indian?’

‘Yes, what about him? What the hell is he doing in this country?’ Gerald’s voice rose and she could see panic bubbling beneath the surface. ‘Why hasn’t he been interned with everyone else, I ask you? Every foreigner, anyone who might assist the enemy, even the poor blighters who’ve escaped from Hitler, has been banged up.’

‘But why should these men be a threat to you?’ She hoped a quiet voice would calm him.

‘They are, I know they are.’

She had never known her husband so agitated, not even in the dark days of mischief in India. His voice had risen even higher and Daisy saw the woman who had just rescued her child’s boat look up, perplexed by the sound.

‘They sent me a white feather. How about that? It was under my door this morning. You know what that says.’

‘Cowardice?’ She hardly dared say the word.

‘Precisely. They’re calling me a coward. The next step will be to denounce me to the authorities.’

‘But how do you know they were the ones who posted it? It could have been anyone in the neighbourhood.’

‘I can’t be entirely sure, but who else would it be? They’ve been watching me closely and they know my movements, know I don’t have a job. And that I’ve a connection with India. They speak to each other in Hindi and I accidentally let on I understood some of what they were saying. That must have made them even more suspicious.’

She shook her head. Gerald was imagining a persecution she was certain didn’t exist. He had built a ridiculous story around two innocent men, interpreting their looks and actions in the worst possible way. It was because he was strung tight by the fear of discovery, she could see, and if he didn’t get away soon, he was going to do something very stupid. She had no alternative. She would have to try to help, even if it meant searching out Grayson and braving a face-to-face meeting with him.

‘I’ll go to Baker Street. That’s where Mr Harte works. I’ll try to see him.’ There was only a slight quiver to her voice.

‘When?’ The question was urgent. Her promise had not been sufficient to calm him.

‘As soon as I have time off.’

‘Soon?’

‘Yes, soon.’ She looked at her watch. ‘I must go now. If I have any luck, I’ll send a message to the address you gave me.’

‘You’ve got to have luck.’ And his tone allowed for no other outcome.

The meeting had been unsatisfactory. He wasn’t sure he could depend on her to go to Grayson Harte. He’d said she had changed and he’d been right. Not to look at. She was still as pretty, prettier if anything. She’d filled out since he’d last seen her, become more womanly. The dark eyes, the darker hair, the skin that in an English climate had regained its smooth creaminess, not quite peach, not quite olive, but soft and clear, still drew him. Was it any wonder he’d lost his head all those months ago in London. It had been a thoroughly boring leave, he remembered, and then he’d gone to buy perfume for the woman he’d decided to love, and there she’d been. Beautiful Daisy. He’d meant only to enjoy a few days with her, but the days had stretched into several weeks and, when he’d left to go back to India, he’d felt real regret. Although not that much regret, he supposed. He’d been looking forward to rejoining his regiment, getting back to the pleasures of life as a cavalry officer. Looking forward, too, to seeing Jocelyn Forester. He’d set his sights on winning the colonel’s daughter and was sure in time that she would reciprocate. The perfume was the first step in his campaign.

But then those pleading letters from Daisy. A baby was coming, she had to marry. And what had that been all about? A miscarriage on-board ship, no baby and a marriage he didn’t want. He’d been angry and he hadn’t treated her well. He didn’t like to think of those days. He’d betrayed her, he knew, betrayed her for money, that’s what it came down to. He’d allowed Anish to talk him into a pit of evil. Just for money, just to pay the debts which terrified him. He’d had no idea that Daisy would prove so difficult, so obdurate, so intent on involving herself in what didn’t concern her. Until eventually she’d faced death. Even now he couldn’t believe that Anish had sanctioned such a thing. It was too awful to think about. He’d done his best to save her, but it had been Harte, the perfect district officer, who’d finally been her rescuer.

No, he didn’t like to think of those days. She’d been a gentle girl when he met her, vulnerable and soft. Now, though, she seemed to have grown a shell and he could only hope that he’d managed to pierce it today. He wasn’t entirely convinced she would do as she’d promised. Something had happened between her and Grayson Harte which made her reluctant to meet the man. She had better though, he thought belligerently. He’d hated having to confess the hole he was in, having to abase himself by begging for help, but he’d had no choice. No choice either about holding a threat over her head. He could congratulate himself on that at least. He’d hit on the right thing—her job—he’d seen that immediately. The threat of having to leave nursing would make her do what he asked, whether she wanted to or not. It would get him the papers, if anything would.

He trudged his way back through the West End and into the City, his feet aching and sore. There had been a big raid two nights ago and the roads were still badly damaged. He’d hardly seen a bus on his way to Hyde Park, but even if one had turned up, he couldn’t afford the fare. He could barely afford to eat and the small sum he’d saved from working in France was dwindling by the day. Look at his shoes—the soles almost falling off, the backs broken down. Dear God, what had he come to? A proud officer in a crack regiment of the Indian Army and now this, hiding away in a dingy, rat-infested room, and dependent on others for his deliverance.

But then he’d always been dependent, hadn’t he? His whole career had rested on a father who’d sacrificed everything for his only son. An ungrateful son. And that was something else he didn’t want to think about. When he’d returned to England, Spitalfields was the first place he’d gone to. He’d had some wild idea that somehow he could reconcile himself with the parents he’d abandoned, the prodigal son returned, that kind of thing. An unspoken thought, too, that maybe his father could get him out of his predicament as he had so many others in the past, though what a poverty-stricken old man could do, he didn’t know. But when he’d rounded the corner of the street—the address had been at the top of the letter his father had sent, begging for money his son couldn’t spare—he’d been appalled. There was nothing, literally nothing. A whole street had disappeared.

After two years of war, he thought, London smelt of death and destruction. Everywhere shattered windows, roofs caved in, water pipes, gas pipes, all fractured, telephone wires waving in the breeze. The people he passed were every bit as shabby as their city since new clothes were a rarity. Shabbier still in the East End where, for a pittance, he’d managed to rent a room. Street after street of mean little houses with open doors and broken windows; filthy alleys in which ragged children played, their pale, pinched faces speaking of years of deprivation before ever the German bombers arrived. And everywhere stank—of waste, of unwashed bodies, of stale beer.

He was walking through the City now, past one ruined church after another, their steeples scorched and dis-coloured by fire. There was something heroic in their tragic silhouettes, he thought, heroic yet futile. They belonged to a past that no longer had meaning. It was the New World that promised, the New World that offered a future. In front of the Royal Exchange, an enormous hole in the road had still not been completely filled after the Bank station had been hit in January. So huge was it that the Royal Engineers had had to build a bridge across for people to get from one side of the street to the other. The East End had fared even worse, of course. Whole terraces mown down and streets almost entirely rubble. Grotesquely, the building on the corner of Leman Street, he noticed, still had a side wall intact and a framed view of a Cornish landscape hanging from the picture hook. He crunched his way along the pavement, littered with shards of glass and cracked roofing tiles. The breeze had begun to blow strongly again and pillows of white dust swirled around him. For a moment he had to stand still, his eyes closed against it.

Turning into Ellen Street, he saw the lodging house ahead, black roof and sightless windows, hovering against the clear blue sky. It loomed discordantly over the dribble of smaller houses, as though it had risen from the pages of a Nordic fairy tale and found itself out of time and out of place. Several of the surrounding properties had been hit on successive nights and had crumbled at one blow. That didn’t surprise him, knowing how shoddily they were built, but at least the debris was light enough for more survivors to be pulled free. Alive but dispossessed. The house adjoining his had had its front cut away as though it were a doll’s house. Skyed high in the air was a dented bath and a lavatory, with a sad little roll of toilet paper still attached to the door. A staircase led to an upper floor that no longer existed. But the house where he lodged had survived all attacks—so far.

He trod up the stairs as delicately as he could. The ground floor of the house was occupied by an old woman, ninety if she were a day, half mad he was sure. He glimpsed her sometimes through her open door crooning quietly to a cat or slumped in a fireside chair, staring blankly at the bare wall in front of her. Sometimes she would stir herself to fling random curses at whoever was unlucky enough to catch her glance but she rarely noticed his comings and goings, being so deaf that a bomb could have fallen outside her window and she’d not have flinched. It was when he approached the first floor that he steeled himself to tread more softly still. He tried to shut his mind to the ill will he imagined lay beyond that door.

His years in the army had given him a nose for danger and he was sure the men who lived there were up to no good. It wasn’t just that they’d ended their conversation the minute they realised he understood Hindi, nor the sheer absurdity of finding two Indians living in the middle of the East End in the middle of a war. It was the nagging matter of why they were there. The Indian might be a soldier as he claimed, and the man’s cap badge seemed to prove it, but why wasn’t he with his regiment or returned to India? And what was the Anglo doing here? You couldn’t trust Anglo-Indians, they were neither one thing nor the other, neither British nor Indian. Some of them had chips on their shoulders for that reason. Did this one? Did the man mean to expose him as a deserter, imagining perhaps that he’d be paid for the information?

He was sure it was this man who’d pushed the white feather beneath his door and that was a warning if ever there was. The sooner he was out of Ellen Street, the better. If Daisy did as she promised and tackled Grayson Harte in the next few days, he might have the papers he needed within the fortnight. Harte could do it if he wished, and he would wish. The man had liked Daisy just a little too much. And his wife had liked him back, despite the doubts her husband had tried to sow in her mind all those months ago when Harte had played at being a district officer. Gerald had no compunction in throwing them together again. ‘Wife’ was just a word now, not that it had ever been much else. For a moment he felt remorse at what he’d done to the young girl he’d met at Bridges. But not for long. There was no point in looking back. And he had no qualms in using Grayson’s feelings for Daisy. Not if it would get him what he wanted.

He put one foot on the stairway leading to his attic. It creaked badly and he froze where he stood on the landing. He tried to breathe very quietly. Were the men on the other side of the door listening? He edged closer so that his ear was almost touching the blistered wood. Inside angry footsteps paced the bare boards. And there were two voices. Both men were at home. He was sure that at least one of them had been following him recently. Several times he’d half sensed a figure at the periphery of his vision and wondered if it was his neighbour. When you said that aloud, it sounded ridiculous, yet … The men were talking loudly, animatedly. Their voices came to him in blurts of noise. He’d heard them argue before, but today there was a new harshness, a new agitation. They were speaking Hindi for certain and the heat of their disagreement was leaving them careless. He caught words here and there, ‘car’, ‘hotel’, ‘Chandan’—was that a name?—disconnected words that made no sense. But he dared not linger and very carefully he placed his shoe on the first step, bracing himself for another agonising creak. Thankfully, the wood remained silent and, on the balls of his feet, he tiptoed up the remaining stairs.

The two small rooms he rented were airless, worse than airless, for the smell of thick dirt was overwhelming and so intense it seemed alive. He could hardly breathe the atmosphere and had to force himself to swallow it in great slabs. The two small windows were glued shut and muslin curtains drooped undisturbed against grimy panes, their colour an elephant grey. Several more flies had buzzed their last since he’d left that morning and now lay shrivelled on the uncovered floor. The room was as dark as it was airless, and through the gloom only the dim outlines of a few pieces of broken furniture were visible.

He flung himself down on to the iron bedstead, pushing aside a tousled heap of clothes. For a long time he lay there, sprawled across the questionable mattress, and trying not to think. His eyes travelled around the brown-papered walls, blotchy and peeling from the damp, and upwards to the pitted ceiling, tracing, as he had done so many times these past few weeks, the cracks that disfigured it. He no longer saw its ugliness but instead had created a map of his own devising. This was him, here on the left, in the centre of that large, brown stain. The mass of small, thin lines stretching westwards were the waves of the ocean he would soon be crossing, and there on the other side of the ceiling, a solid splurge of colour—old paint, he thought, working its way to the surface—was surely the New World beckoning him to its shore. He lay there, looking upwards, for as long as his eyes would stay open.

‘Are you going then?’

Connie punctuated each of her words with a particularly vicious scrub. The urine testing had been done for the day and now they were in the sluice room, grinding their way through the cleaning of bedpans. It was a messy undertaking, mops and Lysol everywhere.

‘I have to. I promised.’ Daisy’s voice trailed miserably beneath the thunder of water. She didn’t want to seek out Grayson, didn’t want to see him again, to see his slow smile and lose herself in those deep blue eyes.

She felt Willa Jenkins looking at them from the opposite line of sinks. ‘Take care, Willa,’ she called across at the girl, ‘there’s another heap of pans just behind you.’