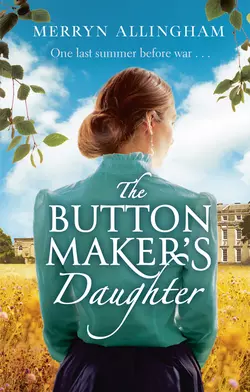

The Buttonmaker’s Daughter

Merryn Allingham

May, 1914. Nestled in Sussex, the Summerhayes mansion seems the perfect country idyll. But with a long-running feud in the Summers family and tensions in Europe deepening, Summerhayes’ peaceful days are numbered.For Elizabeth Summer, the lazy quiet of her home has become stifling. A chance meeting with Aiden Kellaway, an architect’s assistant, offers the secret promise of escape. But to secure her family’s future, Elizabeth must marry well. A man of trade falls far from her father’s uncompromising standards.As the sweltering heat of 1914 builds to a storm, Elizabeth faces a choice between family loyalty and an uncertain future with the man she loves.One thing is definite: this summer will change everything.

MERRYN ALLINGHAM was born into an army family and spent her childhood on the move. Unsurprisingly, it gave her itchy feet and in her twenties she escaped from an unloved secretarial career to work as cabin crew and see the world. The arrival of marriage, children and cats meant a more settled life in the south of England, where she’s lived ever since. It also gave her the opportunity to go back to ‘school’ and eventually teach at university.

Merryn has always loved books that bring the past to life, so when she began writing herself, the novels had to be historical. She finds the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries fascinating eras to research and her first book, The Crystal Cage, had as its background the London of 1851. The Daisy’s War trilogy followed, set in India and London during the 1930s and ‘40s.

Her latest novels explore two pivotal moments in the history of Britain. The Buttonmaker’s Daughter is set in Sussex in the summer of 1914 as the First World War looms ever nearer, and its sequel, The Secret of Summerhayes, forty years later in the summer of 1944 when D Day led to eventual victory in the Second World War. Along with the history, of course, there is plenty of mystery and romance to keep readers intrigued.

If you would like to keep in touch with Merryn, sign up for her newsletter at www.merrynallingham.com (http://www.merrynallingham.com)

To the Lost Gardens of Heligan,

the original inspiration for this novel.

Contents

Cover (#u1bd3a2ac-2d98-54f9-8993-654deba43770)

About the Author (#ufce55c2a-25ff-53cb-8b39-b6ee42630299)

Title Page (#u622c7ed8-3e8c-5655-a448-4a4e3e9c5c2a)

Dedication (#u09109a4e-2f30-5e9b-a3b3-7d0e2b42bbb4)

Chapter One (#ulink_b43be361-3367-52b5-9016-8199929a205a)

Chapter Two (#ulink_bd63aad9-f8b8-538d-af23-c147a0275ec5)

Chapter Three (#ulink_d96d20ab-d4a8-5d87-9549-e7ad37455cbd)

Chapter Four (#ulink_bf3c4929-f41a-5ab2-a599-62ec1c10f06b)

Chapter Five (#ulink_7e302bd5-1be1-519b-a4f8-6dfa59f55d85)

Chapter Six (#ulink_99d5ebf0-020e-5594-bd66-2a3ddb240d6a)

Chapter Seven (#ulink_ea39e3a6-b62a-5252-95f5-006a1fec4671)

Chapter Eight (#ulink_41a6ba84-0d1c-508a-af81-da6aee0a9a73)

Chapter Nine (#ulink_08d094b2-0f57-5db6-9d13-bd1dbee45b4c)

Chapter Ten (#ulink_06972763-9916-5704-a4a8-4bcd1b22c90a)

Chapter Eleven (#ulink_dfba25d1-5647-5f4d-80e7-75bacb92d4d8)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_146d996c-b66c-59a8-ac2e-b4f65cfedc19)

Sussex, England, May 1914

Her father’s voice ripped the silence apart. It burst through the closed doors of the drawing room, swept its way across the hall and rattled the panelled walls of golden oak. From where she stood on the staircase, the girl could just make out his figure shadowed against the room’s glass doors. A figure that was angry and pacing. Carefully, she made her way down the last remaining stairs, then tiptoed to a side entrance. The air was fresh on her skin, cool and tangy, the air of a glorious May evening. A sun that had shone for hours still lingered in the sky and a few birds, unsure of when this long day would end, continued their song.

She walked purposefully across the flagged terrace and down the semicircular steps to an expanse of newly mown grass. Its scent was enticing and she had to stop herself from picking up her skirt and dancing across the vast lawn. It was relief that made her feel that way, relief that she’d escaped the house and its hostility. From a young age, she’d been encircled. Family discord had been a constant. Her parents’ union was what was once known as a marriage of convenience, but whose convenience Elizabeth had never been sure. Their ill-assorted pairing had been a blight, an immovable cloud which hung over everything within the home.

Uncle Henry had done something bad, it seemed. Something to do with the stream that couched the perimeter of both their estates. An act of calculated spite, her father had roared. Whatever it was, she wanted no part of it. She shook her mind free and strode across the grass as swiftly as her narrow skirt allowed, her speedy passage disturbing one of Joshua’s prize peacocks. The bird squawked at her in annoyance and flew up onto the ridge of the stone basin that sat in the centre of the lawn, fanning his feathers irritatedly. He was lucky the gardeners had yet to prime the fountain, or he might have ended more ruffled still. The warm weather had arrived without notice and caught the staff racing to catch up. The roses crowding the pergola that linked lawn and kitchen garden were already unfurling, their scent strong.

She passed beneath the grand arch leading to the huge swathe of land that grew fruit and vegetables to feed the whole of Summerhayes, and felt its red brick humming with the heat of the day’s sun. The tension she’d been carrying began to slip away and her limbs relax into the reflected warmth. Today had been difficult. Her father’s temper, always erratic, had exploded into such fury that the very walls of the house had trembled. At such moments, she was used to finding solace in her studio, paint and canvas transporting her to a world far removed from the sharp edges of life at Summerhayes. But today, painting had failed her. And miserably.

She stopped to listen, the sound of young voices floating towards her across the still air. From behind hoops of sweet peas planted amid the potatoes and cabbages and onions, she could just make out the figures of William and his companion. They were making their way along the gravel path that lay at right angles to where she stood. It was late, too late for them to be out. They were defying the curfew imposed when Oliver had first arrived to spend the long school holiday with her brother.

‘You’d better get yourselves indoors,’ she called out to them, as the boys made their way along the cruciform of gravel that bisected the kitchen garden. ‘Papa is in a towering temper and you’ll be for it if he sees you’re still out.’

‘We’ve been down to the lake,’ Oliver said. ‘We wanted to check on progress, but not much has happened. In fact, just the opposite, the site looks a mudbath.’

‘The stream has stopped flowing,’ her brother put in. ‘At least, I think that’s the problem. The lake isn’t a lake any more. It’s a mess.’

They were near enough now for her to see their grubby trousers and flapping shirts, no doubt a result of the check on progress. ‘You look hideous. If Papa sees you, you’re bound to be punished. Make sure you creep in quietly.’

‘Why is he in a temper?’

Often there seemed no rhyme or reason to her father’s outbursts and, when she didn’t answer, William said, ‘Is it Uncle Henry?’

She nodded.

‘He must have done something to the stream,’ he continued. ‘He did warn that he would if the gardeners kept taking water.’ In the muted light of evening, her brother looked older than his fourteen years.

‘I can’t see why he should,’ Oliver said spikily. ‘There’s a stream three feet deep flowing along the edge of both estates – plenty of water for everyone.’

‘You don’t know Uncle Henry,’ William said.

But if you did, she thought, you would understand his actions as perfectly consistent. Whatever Henry Fitzroy could do to hinder or destroy his brother-in-law’s plans, he would.

‘Go on, both of you. Make haste and use the side door. With luck you won’t be seen.’

‘Likely the old man will still be shouting and won’t even notice we’ve even been out.’

William was becoming cheeky. That was the influence of his more forthright friend and her father wouldn’t take kindly to it. Or to any show of rebellion. Joshua ruled him with a rod of iron and so far her gentle brother had bent himself to his parent’s will, retreating to his mother for comfort. But now Alice appeared to have a rival for his affections. Oliver had become William’s closest confidant. Her brother had been wretched at school, a school their father insisted he attend – until Oliver had appeared at the beginning of the winter term. But Olly, as William called him, had proved a saviour and the change in her brother was astonishing. She could see why they liked each other, why they had come to depend on one another. At school, they were both outsiders, despised by their fellows and teachers alike: William the son of a button manufacturer and Oliver, the son of a Jewish lawyer.

‘Are you coming back with us?’ The light was fading fast and William had begun to look anxious.

‘In a short while. I’d like to take a look at the lake for myself.’

‘You’ll need boots,’ her brother warned.

‘And a dress that’s a few yards shorter,’ Olly quipped.

‘Don’t worry. I’ll not be long.’

She shooed them away with a wave of her hand and carried on along the narrow gravel path that skirted the various outbuildings: past the boiler house, the bothy, the dark house that forced Summerhayes’ rhubarb and chicory and sea kale, and, finally, the head gardener’s office. She glanced across at the huddle of buildings. Nestled together, they made a charming picture but afforded little comfort. The one time she’d visited – for some reason, she had found herself in the tool shed – she’d seen immediately that light was not to be wasted on the workers. The interior had been gloomy, with small windows and little daylight. It was damp and cold, too, since only Mr Harris enjoyed a fireplace, his one luxury in a room of bare boards and battered furniture.

Through another grand brick arch and into the Wilderness. That was the name she and William had given it. Her father insisted it should be called the Exotic Garden but from the start it had been the Wilderness to them, a place where they spent as many hours as possible, hiding from their nursemaid or later their tutor and governess, and hiding from each other.

She came to an abrupt halt. Something was wrong. She stood for a moment and then realised what was missing: she should be hearing the splash of water against stones. A stream flowing to her left, flowing down from the encircling bank and into the lake. But there was no sound of water, no sound at all. The garden seemed to have come to a standstill and an uncomfortable quiet reigned. She took a long breath, then walked through the laurel hedge, the living arch that marked the entrance to her father’s most cherished project, and saw immediately what William had meant.

A little of Joshua Summer’s plan had already been realised. A flagged path had been laid to provide a gentle promenade in a space that was made for the sun, and aromatic herbs planted in the cracks between the paving stones. Beyond and behind the path, bed after bed of Mediterranean plants would find their home and eventually flourish in profusion. On one of the long sides of the lake, a small summerhouse made of Sussex flint and stone had been built, its wooden seats looking out across the water to the terrace and the pillars of what would one day be a classical temple. She could see its foundations from where she stood. They were complete and several of the pillars had already been fashioned and were lying to one side, like giant marble limbs that had somehow become detached from their body. But the magnificent lake, designed to reflect the temple’s elegance, was now little more than a muddy pond, and the statue her father had commissioned – a dolphin whose mouth spouted a constant stream of water – rose, strange and solitary, from out of the ruin.

Somewhere a dog howled. It was an unworldly sound funnelling its way to her through the thick evening air. The hairs at the nape of her neck stood to attention, but almost immediately she realised the noise had come from Amberley, from one of her uncle’s hounds, and gave it no more thought. Picking her way along the flagstones, she had to lift her skirts clear of the sludge before gingerly circling the large oval of dirty water. She had reached the west corner of the temple when a noise much closer to hand startled her. Wildlife in the garden was prolific and for a moment she thought it must be a fox moving stealthily through the tall trees that grew behind the temple, making his way perhaps to the Wilderness to find his tea. But then she heard a cough. A man. And footsteps, soft but unmistakable. The lateness of the hour was suddenly important. She shouldn’t be here. Her mother had warned her often enough that the estate was not secure, that there was nothing to stop a curious passer-by from scaling the six foot wall and enjoying Summerhayes for himself. She took a step back, poised to flee. The gloom of dusk had settled on the garden and the overhanging trees behind the temple workings cast an even deeper shadow across her path. There was a crackle of twigs, a swish of undergrowth.

She turned abruptly.

Chapter Two (#ulink_74113f2e-f992-5909-ba40-ceac1932ad07)

‘Forgive me, I’ve startled you.’

A young man’s slim form appeared from behind one of the prostrate columns. At the sound of his voice, she half turned back. He was hardly the threatening figure her mother had warned of. She fixed her eyes on his face, looking at him as closely as she dared, and was sure she had seen him before. She had seen him before, if only from a distance.

‘Are you the architect?’ she said uncertainly.

‘Not quite.’ He gave a slightly crooked smile. ‘I’m the architect’s assistant, at least until the end of this summer.’

She found herself smiling back. ‘And what happens at the end of the summer?’

‘My apprenticeship will be over. I’ll be the architect you took me for.’ He strode towards her, holding out his hand. ‘I should introduce myself. My name is Aiden Kellaway.’

‘Elizabeth Summer,’ she said, trying not to think what Alice would say to this unconventional meeting. Aiden Kellaway’s grasp was firm and warm.

‘I know who you are. I’ve seen you on the terrace when you take a stroll with your mother.’ He had an attractive face, she couldn’t help noticing. He was clean shaven but his light brown hair was luxuriant, falling in an unruly wave above soft green eyes.

Those eyes were resting on her and she said hastily, ‘You seem to have met a problem here.’ She waved a cuff of shadow lace towards the quagmire.

‘The gardeners have certainly. Mr Simmonds and I will keep supervising the building work, but a temple without its lake is a sad sight. Do you know why this has happened?’

‘Why there’s no water?’

‘I know why there’s no water – I walked upstream for half a mile and saw the dam that’s been built.’

The Amberley estate lay above Summerhayes and Henry Fitzroy had evidently used this advantage to divert the river and render Joshua’s beloved garden a sad joke. Elizabeth felt intensely sorry for her father. He was a rough man. A life devoted to making buttons had not conferred the polish needed to succeed in the highest circles, but for all that her father possessed a deep and instinctive love of beauty.

Aiden Kellaway was looking at her enquiringly. ‘I meant why your uncle – I’m presuming it is your uncle who ordered the diversion – why he should wish to ruin the most beautiful part of a very beautiful garden.’

She wasn’t sure how to answer. She knew the reason only too well but Mr Kellaway was a stranger and she had no wish to confess the family feud. Something in his face, though, invited her to be honest. ‘There is enmity between Amberley and Summerhayes. There has been for years and most local people know of it. Anything Uncle Henry can do to upset my father, he will.’

Aiden shook his head. ‘That’s sad. And to hurt his own sister, too.’

‘I doubt he cares much about my mother. He’s not that kind of man.’ She stopped abruptly. Honesty was one thing, gossiping in this unguarded fashion quite another. ‘In any case,’ she hurried on, ‘the Italian Garden is my father’s idea. Mama never ventures further than the lawn.’

‘Why Italian? Does your father have connections there?’

‘None that I know of, but when he was very young, he travelled to Italy and spent several months journeying northwards from Rome. He still talks of it. He told me one day that it was a revelation to him, how people all those years ago had created a beauty that endured for centuries. I think it made him want to create something himself – something that would delight people for generations.’

Her father’s one Italian excursion, it seemed, had crystallised a yearning that until then had lived only in his heart.

‘Your father is a visionary man. Summerhayes is a wonderful project,’ Aiden said warmly. ‘He can be rightfully proud of creating a glorious site out of what was once barren pasture. Or so I understand.’

‘The gardens are my father’s pride and joy. But the barren pasture, as you call it, once belonged to Amberley.’ She would not spell out her uncle’s jealousy, she had said too much already, but she saw from the young man’s expression that he understood.

He simply nodded and looked out across the swathe of mud to the laurel arch, now faded to shades of grey in the disappearing light. ‘I wonder, though, why your uncle is so opposed. Having such a magnificent garden as a neighbour must add distinction to his own property.’

‘I doubt he’d agree. Amberley is an old estate and Uncle Henry clings to its past glory. My father has the money to indulge himself with projects such as this.’

‘And your uncle does not?’

She would say no more. The subject was too intimate and too painful. Any more and she might reveal the whole sorry business, the transaction between Amberley Hall and her father. A transaction of which for years she’d been only dimly aware.

‘I see,’ was all he said. But she knew that he was thinking through the answer to a question he couldn’t ask: why her mother, a Fitzroy of Amberley, with a family history stretching back to the Conqueror, had married a man like Joshua Summer.

The dusk was closing in and the crêpe de chine dress she had donned for dinner was proving uncomfortably thin. She shivered slightly and he noticed. ‘It’s getting chilly. May I escort you back to the house?’

‘I won’t trouble you, Mr Kellaway. You will wish to be getting home and I can find my own way back, even in the gloom. I know the gardens too well to get lost.’

‘I’m sure.’ He smiled the slightly crooked smile again. ‘But I’m walking your way. My bicycle is waiting for me outside the bothy, though I must be quiet collecting it. The boy on duty has to be up and dressed before five.’

She hadn’t noticed the bicycle when she’d passed by, but that wasn’t surprising. How her father’s men came and went barely impinged on her. Why would it? She lived in a bubble, an affluent bubble, but real life went on elsewhere. Or so it had always seemed.

‘Do you live far from Summerhayes?’

The bicycle had prompted the question but she was genuinely interested. Then she worried that she had been too personal. The rigours of a London Season had not cured her of the candour her mother deplored. Alice’s strictures rang loudly in her ears. They had been repeated often enough for her to know them by heart: A girl should keep her distance from anyone who is not family or a family friend.

Aiden seemed to find nothing amiss with her question and answered readily enough: ‘I have lodgings in the village. A room with board in one of the cottages by the church.’

‘And is it comfortable?’

‘Comfortable enough. Though the cooking could be better.’

‘It’s late. You will have missed your evening meal.’

‘I will. But I’ll get cold meat and pickles instead – my favourite supper.’

She wondered for a moment how cold meat and pickles tasted, and how wonderful it must be to sit at a kitchen table, still in your work clothes, and just eat. No dressing for dinner, no servant hovering, listening to a stilted conversation, and no trudging through course after unnecessary course before escape beckoned.

‘Allow me,’ and before she could protest, he’d tucked her hand in his arm and was steering her along the flagged pathway and out beneath the laurel arch into the Wilderness.

‘This is an amazing place,’ he said, as they followed the winding path towards the walled garden. ‘So many rare and beautiful plants.’

‘My father chose every tree and shrub. They come from all over the world, I believe. He told me that it was plant hunters in the last century who brought them back to this country, and made a fortune doing so.’

‘And each with an adventure attached to it, I’d swear, and a story to tell.’

She wondered what Aiden Kellaway’s story might be. In the cool of late evening, the warmth of his body as they walked side by side was unnerving her, and she tried hard not to think of it.

‘Do you often walk in the gardens?’

She grabbed at the mundane question. ‘I take a turn on the terrace – where you saw me with my mother. Sometimes I venture a little further.’ When I can, she thought. When I can be free of parents, free of servants.

‘Like tonight. What tempted you to wander so far?’

‘I suppose because it was such a wonderful evening.’

They had reached the kitchen garden and in the silvery spread of a just risen moon the most humble of vegetables had taken on a majestic air.

‘I thought it wonderful, too. There was no need for me to stay behind. I could have finished the few tasks I had in the morning, and Mr Simmonds urged me to leave with him. But this evening was too good to waste behind the door of a poky cottage.’

‘Do you enjoy working with Mr Simmonds?’ It was something else she genuinely wanted to know. Questions seemed to be tripping off her tongue tonight, far more than she’d ever needed to ask.

‘He’s a brilliant architect and an excellent mentor. I’ve worked with him for five years and learnt a great deal. I’m lucky he’s one of the old school. He likes to work on site from his own drawings, rather than sit in an office and direct others. And that suits me very well. Since my uncle organised the apprenticeship, I’ve never looked back.’

He stopped walking for a moment and looked down at her. It was as though he needed to dwell on his own words. ‘You know it was a huge piece of good fortune for me that he met Jonathan – at a race meeting, would you believe?’

‘Racing?’

‘Jonathan Simmonds is a bit of a gambler,’ Aiden admitted, walking on once more, ‘but don’t tell your father. He might not like to think his architect has such a weakness.’

‘And you? Are you a gambler?’

‘No, indeed. What would I gamble with? Mind you, my uncle has hardly a penny to his name. But then the Irish can never resist a flutter.’

‘He’s Irish?’ She was learning something new every minute. Right now, though, the Irish were not the most popular of nations. Only yesterday, she’d heard her father fume against the ‘Irish trouble’ and predict that a civil war there was all but inevitable.

‘It’s not just my uncle that’s Irish. I am too.’

‘You don’t sound it.’ He didn’t, though now she was aware, she thought she could detect the slightest of lilts to his voice.

‘That’s because I’ve been in England too long. And my aunt and uncle even longer.’

‘How long? Why did they come to England? Where do they live?’

The bicycle was propped against the bothy wall, as he’d said. He took hold of the handlebars and wheeled it onto the path that led to a side gate and out onto the village road. She stayed where she was and he turned back to her.

‘So many questions, Miss Summer.’ She blushed hotly. He was right. She’d been intrusive to the point of rudeness. ‘But am I allowed one?’

‘Yes, of course,’ she said hastily. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘Then, what are you doing deep in the Sussex countryside? Shouldn’t you be in London, having a fine time?’

‘I’ve had a fine time,’ she was quick to counter.

‘Still… you might enjoy a very different kind of company, away from Summerhayes.’ He pointed to her hands where the faintest traces of paint were still visible. He was far too acute.

‘I daub, that’s all. And I’m happy enough here.’

‘Are you?’

His face glimmered beneath the arc of moonlight and she could just make out his expression. He was considering her intently, as though wanting to drill down into her deepest thoughts, and she found it discomfiting. It was time for her to leave.

Chapter Three (#ulink_29d86891-78c7-54b3-a74a-b68952dbb333)

Alice was on alert and heard the side door of the house click shut. She hoped her husband had not. But Joshua was still talking, still vehement, though a good deal calmer now. He seemed to have talked himself out of his anger and she had no wish to provoke a further outburst. She looked through the uncurtained diamonds of window glass and saw only darkness. What was Elizabeth doing walking in the gardens so late? At last her husband’s voice dwindled to a stop. He would return to her brother’s perfidy soon enough, but, for the moment, she could breathe freely.

‘Shall I call Ripley for tea?’ she asked hopefully.

He didn’t answer but shuffled to the edge of the sofa, then heaved himself to his feet and trod heavily across the polished oak floor. He enjoyed using the telephone, she knew. It was modern and efficient, two words that were his touchstone. His hand had reached for the instrument when she said, as casually as she could, ‘Did you think any more about the finishing school?’

‘I did not. And the answer is still no.’ He turned to face her, a grimace enlivening his otherwise stony expression. ‘I thought I’d made it plain that Elizabeth has no need to attend a foreign school. In my view, she is perfectly finished already.’

‘She is a credit to the family.’ Alice used her most emollient tone. ‘But would it not be a good idea to allow her to travel a little before she settles down? You have said yourself how wonderfully foreign travel broadens the mind. And, in Elizabeth’s case, it would be particularly beneficial. She would have a new setting in which to paint.’

‘She can paint here. She has her own studio, dammit. And as for travelling, she travelled more than enough last year and didn’t like it. This is where she belongs.’ He stomped back across the polished boards and spread his bulk along the printed velvet of the sofa. The effort pulled the Norfolk jacket tightly across his chest, its buttons looking ready to pop.

‘She travelled to London,’ Alice said mildly.

‘Exactly. And isn’t London the greatest city in the world? Even greater than Birmingham, though some would argue differently.’ His lips pulled back into the slightest of smiles. When his wife failed to acknowledge the pleasantry, he glared at her. ‘Where else should she go?’ he asked belligerently. ‘I don’t want her in Europe. Europe is a dangerous place – more so with every month that passes.’

‘But how is that possible? You are still in touch with Germany, are you not? Surely people there won’t want trouble. Or in France or anywhere else for that matter.’

‘Trade is one thing, war another. I’ll keep contact with Germany as long as it remains a good customer. The old factories do well from it. But it doesn’t mean I trust them. I don’t trust the man who leads them. The Kaiser is a swaggerer and he’s unpredictable; he’ll make trouble, mark my word. It may appear quiet at the moment but the Germans have the greatest army in the world – that’s something we should never forget. And now it has a navy to rival ours. They’ve been building a fleet large enough to threaten us at sea. Did you know that?’

She shook her head. She was hazy about the politics of Europe and could not argue. Not that she would, if she’d been Emmeline Pankhurst herself. It was not what women did. But, surely, Elizabeth would be safe in one of the best schools in Switzerland? And her daughter would gain so much from the experience. Different people, different customs, and encounters that could prove important. Introductions. Introductions that could lead to marriage and put the wild ideas Elizabeth had out of her mind. It was typical of Joshua that he couldn’t see the need for his daughter to widen her horizons. Summerhayes was the only horizon he could contemplate and what was right for him must be right for Elizabeth. But if the girl were to remain here, things could not stay the same. She approached the subject tentatively.

‘If Elizabeth is not to go to Switzerland, we might look for a suitable husband.’

‘She had the chance to find a husband and chose not to.’

He wanted to keep his daughter here. Keep her under his fond but watchful eye. And part of her sympathised. Marriage wasn’t the gilded promise that mothers held out to their daughters. She, of all women, should know that. But the girl’s future had to be considered. Joshua wouldn’t always be here and neither would she. Far better that Elizabeth had a home of her own long before that happened. And her daughter would have choice; she would not be forced to marry for money, as her mother had been.

‘London may have been the wrong place,’ she persisted. ‘The men she met there were not perhaps right for her.’ Though goodness knows what kind of man would attract her wayward daughter. ‘Someone closer at hand, someone from our own county, might suit her better.’

Joshua’s shoulders tensed in an angry fashion and she began to think it wise to abandon the conversation, when a quiet knock on the glass doors of the drawing room heralded Ripley and the tea tray. Her husband was forced to swallow his rancour but, when the footman had poured the tea and departed, he said, ‘Why can’t you leave the girl alone? She’s still young. She is happy here. Let her be.’

‘She is nineteen years old, Joshua. In a few months’ time, she will be twenty. She is in her prime, a time of her life when she should have the pick of husbands.’

‘Not like you, you mean.’

The warmth crept into her face and she took hold of the teacup with an unsteady hand. She hadn’t wanted the pick of husbands. She’d only ever wanted one, but a solicitor’s clerk was never going to match Fitzroy ambition. She had loved Thomas with the purity of the very young, and known herself loved in return. But their fate had been inescapable. Once discovered, the boy had lost his position and been harried out of Sussex. By the time she was despatched to London – a last-ditch attempt to save Amberley – her place was already reserved on the shelf for redundant spinsters.

She could still feel the humiliation of that summer in London. The Season had cost her family dear but failed to attract any offer of marriage, let alone from a man with money. That hadn’t surprised her. Since she’d lost Thomas, she had made little effort to please, and she knew she was judged unattractive and insipid. But her family had seemed strangely unprepared for her lack of success, her brother in particular. He’d been a stripling then but it hadn’t stopped him from reminding her, whenever opportunity offered, that she was an unwanted daughter. There had been a barrage of unkind comments – on her appearance, on her lack of personality. And it hadn’t stopped at taunts. On occasions, he’d grabbed her by the shoulders and physically shaken her or pinched an arm or a hand as he’d passed her chair, just to make sure that she wouldn’t forget the family’s disapproval. When she’d returned from London, it was with little hope of ever finding a husband. And even less hope of Amberley ever securing the money that would ensure the estate remained in Fitzroy hands. Until Joshua arrived in Sussex.

‘No, not like me.’ She had taken time to recover her composure. ‘Elizabeth’s situation is very different. There is no need for any kind of business arrangement.’

‘Considering how our business arrangement has worked out, it’s as well.’ He glowered at her and she was fearful that he would start once more on Henry’s most recent act of malice. But he was too busy brooding over past insults.

‘I saved your family from bankruptcy, poured thousands into Amberley, and what was my reward? It took me years to wrench land from your brother, land I was owed, land that your father had signed over. I had to go to law, expend even more money to get what was rightfully mine. And the result? Your brother has made trouble wherever and whenever he can. It’s clear he won’t be satisfied until he reclaims Summerhayes for his own. And, good God, wouldn’t he like to! A ramshackle manor house and the poorest of ground transformed. He longs to get his hands on what my wealth has created.’

There was a long silence while he drank his tea and looked through her at the wall behind, William Morris’s manila daisies seeming to grip all his attention. Whenever her brother acted badly, the old bitterness broke out anew. First her father, then Henry, had attempted to renege on the marriage agreement, and every tactic, every subterfuge, every gambit used to prevent her husband taking possession of land that was rightfully his was engraved on Joshua’s heart.

She had picked a bad time to raise the subject. She smoothed the creases from the messaline silk, one of the many expensive dove-coloured gowns Joshua insisted on buying, and took the empty teacups to the tray. He looked up as she did so, coming out of his studied gloom.

‘You must drop this idea of brokering a marriage, Alice. It will spell disaster. And there is no need for us to do a thing. Elizabeth will stay at Summerhayes and one day a young man will come along who takes her fancy. I’ll be able to inspect him, make sure he’s the right sort. And if he is, I’ll make him welcome. He can join me in the management of the estate, take some of the weight off my shoulders since William looks unlikely ever to do so.’

‘William is only fourteen.’ In defence of her youngest, she lost her timidity.

‘He is old enough to take an interest, but he remains a child. He hasn’t a serious thought in his head. And that boy you’ve invited here – Oliver, isn’t it? – if anything, he’s worse. Playing tricks on the servants, laughing in your face. The boy has no respect. But what can you expect coming from a family of Jews? That’s a little matter you didn’t tell me about.’

Oliver’s family was something to which she’d given no thought before agreeing to the boy’s stay, and she felt guilty at her oversight. But then there was rarely a moment when she didn’t feel guilty.

‘Once we can send him packing,’ Joshua pronounced, ‘he doesn’t come again.’

She wasn’t going to argue for Oliver. She wasn’t at all sure herself of the young boy’s suitability. Instead, she steered the conversation back to Elizabeth.

‘You wouldn’t wish Elizabeth to get into trouble,’ she said cautiously.

‘Of course, I wouldn’t. What are you talking about, woman?’

‘She’s young and headstrong. All this nonsense with the suffragettes – it’s had an effect on her.’

Joshua gave a loud tsk. ‘Don’t mention those women in my presence. They are a scandal, a disgrace to their sex.’

‘Elizabeth reads the papers. She is aware of what is happening beyond our sleepy corner of the country.’

‘Is she intending to create a disturbance, too, then?’ He gave a snort of derision. ‘In parliament perhaps or maybe at the racetrack. Should I give her a little hatchet, do you think, so she can join her sisters in slashing the nation’s works of art?’

‘I’m sure Elizabeth has no such ideas,’ her mother said seriously. ‘It’s their talk of female independence, female equality, that has caught her imagination.’

She saw that at last he was paying attention. ‘What has she been saying?’

‘Only that she sympathises with their aims. And that a woman should be able to decide her own future.’ This latter sentiment was barely murmured.

Despite his corpulence, Joshua bounced up from the sofa, his annoyance lending him flight. He began to pace up and down the drawing room, backwards and forwards across the soft tufts of the Axminster, until he had bruised its thick pile into a clearly marked track. He came to rest, towering over her.

‘And what precisely does that mean – decide her own future?’ His growl threatened trouble. ‘Doesn’t she have future enough here with me? I’ve been a good father; some would say too good. I’ve let her twist me to her wishes more times than I care to remember.’

‘You have,’ she soothed. ‘But perhaps as a good father, as good parents,’ she corrected, ‘we should take time to look for a suitable husband. A man who could guide her and guard her from getting into – trouble.’

‘And where do you propose to find him?’

She was glad he didn’t question the nature of any trouble. In some ways, she knew their daughter better than he, knew her wilful nature, the passion of which she was capable. For a clever man, he could be amazingly blind. He had only to look to himself to see his daughter mirrored there. The hours Elizabeth spent in her studio could only go so far in sublimating such feelings, Alice reasoned, and the thought of trouble was never far from her mind. Elizabeth’s solitary walks did nothing to calm her. A gently reared girl did not walk alone and certainly not after sunset – her daughter knew the rules well enough, but took no heed of them.

When she didn’t answer, he warned, ‘If Elizabeth should ever marry, it must be to a man of stature. I’ll not have her marry beneath her – a tradesman or some such.’

It was a perfect irony. Joshua was such a tradesman, a very rich one it was true, but a tradesman nevertheless. The fact that he appeared oblivious to the contradiction gave her the courage to confess what she had in mind.

‘We should, perhaps, look to family connections. My family connections.’

‘I married you for your connections, remember, and where has that got me? And since you are all but separated from your family, it’s not likely to get us anywhere now.’

She ignored his jeering tone and took a slow breath before she said, ‘Henry might aid us.’

He gave a bitter laugh. ‘Aid us! The man has done nothing but cause harm, or try to, since the moment I dared to reclaim what was mine from his penniless estate.’

She disregarded the slight to her family home and pushed on. ‘But this might be something with which he would be willing to help.’

The Fitzroys had saved their estate through marrying her to Joshua, but they had also lost caste. Another marriage might help them regain it. Henry had hated the necessity that assigned her to Joshua – she’d sold herself, he had said – even though it was he who had encouraged their father to sign the contract. He who had placed the pen in the older man’s hand. Might this be an opportunity then to salvage some honour from a bad deed?

‘Elizabeth is his niece,’ she went on, ‘and a good marriage would redound to his credit as much as ours. She is a beautiful girl and there is nothing to say she could not make a very good marriage.’

Joshua was silent. She had given him pause. Last year, he had been furious with his daughter for rejecting two acceptable suitors, but his anger hadn’t lasted. Deep down, she knew, he’d wanted to keep his daughter by his side. But if, after all, Elizabeth were to make that splendid marriage, it would be a crown to his career. A trumpet call announcing to the world that here was a man who was as good as any of his neighbours.

He walked slowly over to the blank window, a new pair of balmoral boots creaking beneath his weight, then turned and frowned at her.

‘You’ll have to tackle him then. He’s your brother. His latest act of spite makes it intolerable that I should exchange even a “good morning” with the man.’

She was not a courageous person, but where her children’s welfare was concerned, she could fight as well as the next woman. Any suggestion that Joshua had not thought her brother worthy of consulting on such a delicate family matter would antagonise Henry even further. If that were possible.

‘The approach will only be successful if it comes from you, Joshua,’ she said firmly. He didn’t, as she expected, immediately rail at her and she was emboldened to continue, ‘We will see the Fitzroys in a few days – at morning service. And church might be the very place to make peace with them.’

Again, Joshua said nothing. She had no idea what he was thinking. All she could hope was that her words had hit home and, come Sunday, he would unbend sufficiently at least to speak to his brother-in-law.

The difficult evening had taken its toll and her head had begun its familiar ache. She rose from her chair, stiff from sitting so long. ‘I’m feeling a little weary. And I need to check on William before I retire.’

‘At his age! Ridiculous! You mollycoddle the boy,’ were her husband’s parting words.

She said nothing in reply but walked out into the hall. She would look in on the boys before she slept. Satisfy herself that all was well with her youngest and dearest. As for the business of Elizabeth’s marriage, she hoped she’d said enough to begin some kind of thaw. The Summer family led a lonely life and if Henry could be persuaded to introduce one or two likely suitors to their restricted circle, then youth and proximity might do the rest. It was important that her daughter find the right man, a man she could love and respect. Not for Elizabeth the pain of an ill-assorted liaison or the indignity of being bought and sold in a marriage made by others for others. Not an arranged marriage, but an encouraged one. That was a more comfortable thought.

Chapter Four (#ulink_6130a6ea-67a9-5653-ad65-28596cf04798)

William’s door was slightly ajar and she pushed it open a little further. The room was large and high-ceilinged, its tall windows giving onto a rolling expanse of green and filling the space with light and air. It was the room William had chosen for himself when he’d emerged from the nursery. She remembered how proud he’d been, a small boy sleeping alone for the very first time. The room might be spacious but there was barely a spot that was not filled to overflowing with evidence of the passing years. Over time, her son had followed many interests, this shy, sensitive boy with his finely honed curiosity. This summer, it was nature that had taken hold of his imagination – several boards stood at angles to the the wall, displaying leaves of every shape and size and colour, all carefully mounted and labelled. The large wooden desk she’d had the men bring down from the attic stood beneath the window and was piled high with reference books. The Trees of Great Britain & Ireland lay open on the floor.

But the toy theatre that had once dominated William’s time was huddled against the far wall. Cornford had been skilful in producing a facsimile stage made of wood and cardboard, with a row of tin footlights with oil burning wicks along the front. For years, every penny of William’s pocket money had been spent on sheets of characters and scenes. He’d managed to persuade Elizabeth to write several short plays and even help him perform them. Since then, the theatre had been supplanted by other hobbies, as once it had supplanted the regiments of lead soldiers. They were crammed into a battered wooden trunk, along with the clockwork train that had once run the circumference of the room.

But there in the centre was what really mattered – two beds, side by side, and two boys sleeping soundly, exhausted by their day in the sun. How well her son looked! Oliver would never be a favourite with her but it was enough that William liked and trusted him. She allowed herself a satisfied smile and backed quietly out of the room.

At the sound of his mother’s approach, William had shut his eyes tightly. He didn’t want her fussing over him, asking him why he was still awake, offering to bring medicine to help him rest. He wanted simply to lie there, to lie and watch Oliver sleep. He’d been watching him ever since his friend had drifted into a deep slumber. Olly was stretched lengthways down the bed, the covers thrown to one side. One arm was propped beneath his head, his dark hair a clear contrast to the white linen of the pillowcase. The other arm lay outside the covers, slightly bent towards William and, in the narrow beam of moonlight that crept between the drawn curtains, he could see the small dark hairs on Oliver’s arm. They looked soft and inviting, and he felt a strong impulse to reach out and stroke them. It left him confused, disturbed. Olly was his friend. That was the sort of thing you did with girls, he’d heard, though he could never imagine himself touching a girl. You didn’t do it with friends. Chaps pushed each other around, cuffed each other’s ears in play, but that was different. Everyone did that. What would Olly say if he woke to find his friend stroking his arm? He would think William had run mad and he’d be right.

This was the first time they had ever shared a bedroom, since at school they slept in different dormitories. And they were taught by different teachers, too, so their hours together were precious. They would meet at break times, meal times as well, and after prep if it were possible. It was Olly who had rescued him one evening from Highgrove’s biggest bully and that kindly act had cemented their alliance. Since then, they’d become the best of friends. The two musketeers, Olly had called them. How right that had felt; it hadn’t seemed to matter then that he didn’t fit in, would never fit in. It wasn’t just his background that was wrong, it was the way he felt. That was all wrong, too. When his classmates whispered about girls, it made him curl up inside. He pretended to be interested, anything to keep from another beating, but those sniggering conversations made him feel odder than ever. He couldn’t imagine wanting to do what the boys spoke of.

He looked across at Olly again, his gaze fixed on the boy’s beautiful skin, and was awash with a strange hollowness. Bewildered, he tossed himself to the other side of the bed, his back to Oliver. At school, there were rules to follow, orders to obey, and daily life was cut and dried. But these last few weeks had been different. It was this magical summer that was at fault. That and the beauty and freedom of the gardens. It was being at Summerhayes that was making him anxious. Nothing was cut and dried here. Not with Olly. Boundaries seemed to be dissolving, growing fainter every day. There was nothing to grasp, no certainty to hang on to. How was he to deal with that?

Chapter Five (#ulink_04572deb-4e28-50af-b34d-0d03ce04286c)

‘Miss Elizabeth! Wake up, Miss Elizabeth. Your father wants you downstairs.’

With the tug at her bedclothes, Elizabeth surfaced slowly from a very deep sleep. She opened her eyes the barest fraction, shielding them with her hand from the brightness in the room. It was gilding the satinwood furniture with its brilliance and had settled in a pool of gold on the embroidered bedspread directly beneath her feet. She glanced at the carriage clock on her bedside table. It was very late. Sunday was no day of rest at Summerhayes and right now she should be at the breakfast table.

‘Thank you, Ivy.’ She took the teacup the maid was offering.

Between yawns, she sipped at the hot liquid while Ivy’s black-clad figure moved quietly around the room, gathering up items of cast-off clothing and sorting them for washing or mending. As soon as the maid judged her mistress sufficiently awake, she drew back the curtains, their stencilled linen vivid in the bright sunlight. A vista of soft green and splashed colour crowded in on them.

‘It’s going to be another fine one, by the look of it.’ She smiled at the day’s promise.

‘That it will, miss.’ The girl wore an even wider smile. ‘And what dress will you be wearing?’

‘I don’t know. Nothing special – it’s only Sunday service.’

Then she thought again. Would Aiden Kellaway be at church this morning? It was possible, if he had lodgings in the village. It was possible that he’d been in church all these weeks past, but she hadn’t known. She shook her head at the thought and then realised how odd she must look. But if she were thinking at all sensibly, he wouldn’t be there. He must be a Catholic and would never attend St Mary’s. Or he was busy and still working in his spare time on the temple plans. Or he was simply godless. Her mind swung wildly from one proposition to another, until she became quite cross with herself. It shouldn’t matter whether he was there or not, but somehow it did and the fact annoyed her greatly. She’d already spent far too long thinking about him.

And far too long growing annoyed. She’d been ruffled by him, ruffled by his assumption that she wasn’t happy at Summerhayes, and knowing he was right only added to her annoyance. She wasn’t happy. Life on the estate was dull – no one visited and nothing happened. But her dissatisfaction went deeper than that. While she lived here, her art would remain hidden. There was little chance of ever becoming the professional painter she longed to be. In London, it might be different. But then she hadn’t been any happier there and had been glad when the Season ended. Plunged into a summer of flower shows and exhibitions, races and regattas, she’d found society frenetic. It was not the London she wanted or needed. She’d danced at ten balls a night, but the mad tempo masked a falsity that struck her acutely. She’d not belonged there any more than she belonged at Summerhayes. But she didn’t need a man to tell her that, and a man she barely knew. This morning she would show herself content with her world – just in case he was there.

‘I’ll wear the Russian green,’ she decided. And when Ivy looked uncertain, added, ‘The moiré silk the dressmaker delivered last week?’

‘I remember – such a handsome dress,’ her maid enthused. ‘I hung it behind the green cloak, but you’ll not be needing that this morning! The colour will show off your hair something lovely though. Will you wear it up?’

‘There’s no time. Just pin it back and maybe we can find a ribbon to match the dress.’

Ivy went busily to work, pulling the gown from the wardrobe and laying it across the old nursing chair to hang out the creases. Various pieces of underwear were whisked from the chest of drawers and then she was delving into the squat wooden box that sat on the dressing table in search of a ribbon. All the time, the girl hummed quietly to herself.

Elizabeth swung her legs out of the bed. ‘You sound remarkably happy.’

‘I should be, miss. It’s my banns today.’

‘Of course, it is. I’m so sorry. I’d forgotten.’

‘I don’t mind. Neither does Eddie. We don’t want a lot of fuss and bother. The next three weeks the banns will be called and then we can lie low for a while.’

‘It’s September, isn’t it? The wedding?’

‘We’ve fixed it for the fifth – we’re saving hard.’

Elizabeth knew that money was scarce for them both and had wondered if she dared ask her father to raise Eddie’s pay. Cars were still a novelty in the countryside and chauffeurs even more so. But when the gleaming dark green Wolseley had arrived from Birmingham last year, Eddie Miller had performed the small miracle of transferring his driving skills from horse to car. The day he’d donned a motoring uniform of drab grey, together with leather gauntlets and leggings and a visored cap and goggles, he had become an entirely different man from the groom who only weeks previously had flicked his whip at a recalcitrant horse. Surely he deserved reward for that. And reward, if Joshua only knew it, for refusing her request that he teach her to drive this mechanical beast. That had been a step too far, even for a warm-hearted Eddie.

She wanted to help the couple, but she was nervous of tackling Joshua in his present mind. Her father had been mercifully quiet these last few days, but it didn’t mean he had forgotten his anger over the derelict lake, and the smallest annoyance could light the spark again.

Aloud, she said, ‘Is the bathroom free, do you know?’

‘I’ve the bath running now. Master William and his friend were in and out of there this morning like the shake of a lamb’s tail.’

‘I bet they were!’

When she walked into the breakfast room half an hour later, it was to find the silver salvers lining the buffet table almost empty. The family had already eaten. She forked a slice of ham and started to spoon scrambled egg onto her plate, but then for the second time that morning saw the hands of the clock. There was no time and she would have to go hungry. She hurried out into the hall, skimming its black and white chequered tiles, and out of the front door where the small family group had gathered to wait.

‘You’re not driving us this morning, Eddie?’ The car stood gleaming on the driveway and Eddie Miller, dressed in his Sunday best, was gently flicking the last spot of dust from its shining chrome.

‘Them’s my orders, Miss Elizabeth. But I’ll be in church, alongside Ivy.’

‘Of course you will. Your banns are to be called today.’

His face lit with a warmth she could almost touch. ‘It’s a special day for sure,’ he said, ‘and your pa was agreeable to walk. It’s not often Ivy and me get to be in church together.’

Ivy, she knew, would make sure her intended went to at least one service on a Sunday. Now that the couple were to marry and occupy the rooms above the motor house, it would be more important than ever to keep the master happy. Not that her father was a devout man, but aping the manners of the aristocracy had become essential to him, and a servant who did not attend church would be a discredit.

Joshua had a detaining hand on Oliver’s arm and was pointing upwards to the half timbering on the front façade of the house, lecturing the bored youth on how his personal choice of weathered, unstained oak had so beautifully blended a modern Arts and Crafts mansion into the landscape.

He stopped mid-sentence when he caught sight of his daughter and walked over to her. ‘You’ve made us late,’ he grumbled, but softened the words by smoothing an errant strand of hair from her forehead.

‘If we walk briskly, we will be in good time,’ Alice said pacifically, unfolding her sunshade. ‘And a walk should help curb some high spirits.’ She looked pointedly towards Oliver, who, having escaped Joshua’s grasp, had taken to kicking loose gravel along the drive and was attempting to inveigle William into a competition.

Her father sounded an irritated harrumph and rammed a felt homburg onto his head. He pointed his cane at the lodge gates ahead. ‘Come,’ he ordered.

They came, trooping after him down the magnificent avenue of ornamental dogwood, its profusion of creamy bracts just beginning to unfurl their enormous waxy flower heads. Behind the family, the first group of servants, out of uniform but soberly dressed, followed at a respectful distance. She was glad she had worn her second-best boots, Aiden Kellaway not withstanding. It was less than half a mile along a country lane to the tiny village green and the Norman church that overlooked it, but quite long enough for new boots to pinch.

The walk this morning, though, was delightful. Banks of primroses shone yellow on either side of them and beneath the shade of the hawthorn hedge, the deep, sweet smell of bluebells filled the air. Above, swallows skittered across a sky of unclouded blue. She wondered whether this might be the time to broach the subject of Ivy’s marriage. The morning was the most beautiful nature could bestow and her father was striding out as though, for once, he had a real wish to attend church. But when she drew abreast of him, his expression was anything but promising and she decided she would wait her moment. All would depend, she guessed, on the meeting with Henry Fitzroy. This would be their first encounter since the lake debacle. The Fitzroys were bound to be in church; they never missed a Sunday, never missed the chance to sit ostentatiously in the family pew. Alice had as much right as they to a seat there, but she never took it. The Summer family sat to the rear; years ago, a tacit agreement had emerged within the congregation that this was where Joshua’s family belonged. Her mother did not appear to mind the discrimination and the thought crossed Elizabeth’s mind as she entered the church that Alice was glad to be away from her brother. She was scared of him. Why, she didn’t know. Uncle Henry had never scared her.

She could see him now. He was a tall man and his head and shoulders were clearly visible through the nodding plumes and feathers of the women’s toques, donned for this special moment of a special day. He sat rigidly straight, his glance never deviating from the stained glass figure immediately ahead. The window, fittingly donated by the Fitzroy family, held the image of Jesus in an unusually martial pose. Aunt Louisa sat to one side of her husband and, next to her, Dr Daniels. That seemed odd. It appeared they had a lot to say to each other, small sharp whispers between the hymns or as Eddie Miller’s and Ivy’s banns were read or as the vicar made his way to the pulpit. She wondered if her aunt or uncle might be feeling unwell, to need the doctor in attendance.

When the last prayer had been said, the congregation trickled from the church to shake the minister’s hand as he waited in the porch to greet them. She had thanked him for his sermon and begun to walk along the brick path to the lych gate, when she realised that her mother still lingered by the church door. She looked around and saw her father taking an inordinate interest in several of the more ancient tombstones, their engravings barely visible beneath the lichen. Of William and Oliver there was no sign. They had sat almost entirely silent during the service, and she’d been about to congratulate them on their forbearance, when like two young colts freed from harness, they had chased off, one after another, to the fields that lay at the back of the church. Her mother appeared distracted and seemed not to have noticed.

It was a feeling Elizabeth shared when Aiden Kellaway emerged from the stone porch and came up to her. She had not seen him in church, had hardly dared look for him. And now he was here, in person rather than in thought, and she was most definitely distracted. He looked a good deal smarter than when she’d encountered him in the Italian Garden, though his hair had not remembered it was the Sabbath and still waved wildly across his forehead.

‘Good morning, Miss Summer.’

Her mother turned sharply at the unfamiliar voice and she became conscious that Alice’s eyes were fixed on them.

Her colour mounted. ‘Good morning, Mr Kellaway. I hope you are well.’ She tried for a neutral tone.

He gave a small nod. ‘And you, Miss Summer?’

‘Indeed, yes. And how is your work progressing?’

‘Well, I thank you. And yours?’

‘My work?’ She sounded bewildered.

‘Your painting.’

That left her more bewildered still and very slightly affronted. Art was not work, not in her world. It was an acceptable hobby for a young woman, that was how her family thought of it. And most other families, too. There were women, she knew, who’d escaped the straitjacket, a few who’d attended art school and were even painting for a living. Laura Knight, for instance – she’d heard her spoken of last year in London. But they were exceptional and she was not. At Summerhayes, she remained alone in sensing the true nature of what she did. Alone in knowing the passion that gripped her. But it was a secret, brooding passion, and one she had never shared.

‘It’s going well,’ she stuttered, thinking of the lake scene now emerging from the canvas in her studio. ‘But tell me about the temple.’

‘Tomorrow we raise the first of the columns – it’s an important moment. We should have a good idea then of how the finished building will look. But I fear the lake will be a blot on the picture.’

‘The stream is still dammed then? I’m sorry to hear it.’

She was burbling. She must sound ridiculous but she had to say something. For days, she’d allowed her mind to conjure an image of him, hear his voice, imagine a conversation. Now faced with the reality, she was flustered and flailing.

But he treated her remark seriously, or had the good manners to do so. ‘As far as I know, the situation remains the same. Though I sense there may be moves afoot.’

‘In what way?’

‘I’ve a feeling it’s to break the dam that has been constructed, though I know little of what’s planned.’

It was probably as well to know little. Breaking the dam sounded altogether too grave, but his words reminded her that her father had yesterday been closeted with Mr Harris and several of his men for some hours.

‘You must pay the Italian Garden another visit,’ Aiden was saying, ‘and see the temple as it rises. There’s an excellent view from the summerhouse and the pathway around the lake has now dried completely. We have been lucky with the weather.’

‘It would be good to see it,’ she said impulsively.

But then checked herself. Would she go? She found herself looking into a pair of misty green eyes and thought that she might. Her mother would be shocked by such forwardness, and her father disapprove heartily of her mingling with men he considered servants. But the chance of a small adventure was enticing.

She became conscious that Aiden was looking at her in the same intent way that earlier she’d run from, and found herself trying to fill the silence that had grown between them. ‘At least today you can forget about the temple. Sunday must be a day of leisure, even for you.’

He smiled down at her and she grew warm beneath his gaze. ‘Will it be meat and pickles for lunch?’ she gabbled. She’d remembered the supper he’d spoken of and there was something that appealed to her in that simple meal.

‘No, indeed.’ His eyes lit with laughter. ‘On Sunday, Mrs Boxall treats her lodgers to a feast – a leg of lamb at the very least. A trifle singed around the edges, but nevertheless roasted meat. And, if we’re lucky, a slice of Sussex Pond pudding to follow.’

She was about to ask him how such a pudding tasted, when her mother called to her. Whatever had distracted Alice, it was not weighty enough for her to ignore her daughter’s protracted conversation. ‘Elizabeth,’ she called sharply, ‘I need you here.’

She was apologetic. ‘Enjoy your meal, Mr Kellaway.’

‘And yours too, Miss Summer.’

‘Who was that?’ her mother asked, as she reached her side.

‘One of the men working on the temple, Mama. He is apprenticed to Mr Simmonds.’

The information seemed unwelcome. ‘You should not be talking to him for so long,’ Alice scolded. ‘Your place is beside me.’

She felt the familiar wash of suffocation, the familiar burn of annoyance. But any urge to challenge her mother died when Henry Fitzroy and his wife emerged from the church, their son and his tutor a step behind. Dr Daniels was at the rear of the small party. She hadn’t noticed Gilbert in the church, but of course he would have been there. Her young cousin was too small and too quiet, altogether too quiet. She saw her aunt bend her head towards her son, the large plumes on her headdress almost smothering him. Louisa was looking extraordinarily smart, she thought.

‘Greet your uncle and aunt, Elizabeth,’ her mother almost hissed into her ear.

‘Good morning, Uncle Henry, Aunt Louisa,’ she said obediently.

Henry stopped mid-path. ‘Good morning.’ He doffed his hat abruptly and then went to move on.

‘Henry, we need to speak to you.’ Her mother sounded bold. ‘Louisa, you too. On a private matter.’

The doctor by then had drawn level with them and looked surprised, but he bowed a polite farewell and walked on. Louisa, looking equally surprised, hustled away her young son and his instructor, then took up position in the lea of her husband, casting an uneasy eye at him. Elizabeth, too, was uneasy. It looked very much as though another confrontation might be looming – Joshua’s anger over the destruction of his lake still burnt brightly – but surely not on a Sunday and not on consecrated ground.

While she was trying to make sense of the situation, her mother turned back to her. ‘Go and find William,’ she said abruptly.

She blinked. She had never heard Alice sound so commanding. And hadn’t she just been instructed to stay by her mother’s side? ‘Go!’ Alice urged, when her daughter remained where she was.

She gave the slightest shrug of her shoulders and went.

Chapter Six (#ulink_eb5eb276-0bb5-5eac-a1c4-9231eb22383a)

‘What is all this?’ Henry said roughly.

‘We are hoping the unfortunate events of the last few days can be forgotten. Are we not, Joshua?’ Her husband’s marked reluctance to join them had sent her spirits sinking. ‘Are we not?’ she asked again, a little despairingly. At that, he gave the required nod, but without conviction.

Henry drew himself to his full height, his chest resembling a pouter pigeon in full strut. ‘The events, as you term them, Alice, are not in my view the slightest bit unfortunate. They follow from your husband’s determination to purloin water from my estate.’

Joshua took a step forward. ‘The water is as much Summerhayes’ as it is yours,’ he began dangerously.

Alice stepped between them. ‘Please, there has been too much argument already. Henry, you have made your point, I think. We are kin and we should not be quarrelling in this way.’

‘Kinship appears to mean nothing to your husband –’ again her brother refused to use Joshua’s name, ‘– but he would do well to remember the importance of family connections.’

‘Such connections mean a lot to both of us,’ Alice protested, ‘and particularly now.’ She looked across at Joshua. Why wasn’t he helping her? He had promised to play his part, but instead was standing blank faced, a pillar of granite.

Louisa, who until this moment had remained a silent onlooker, suddenly expressed an interest. ‘Why now?’ she asked, glancing up at her husband as though seeking his approval.

She is hoping for scandal, Alice thought. Her sister-in-law might come from a high-born family, but she had always an ear for gossip, with conversation that would fit her for the servants’ hall.

‘We wish to talk to you about Elizabeth,’ Joshua put in unexpectedly. ‘She is your niece, after all.’

‘I’m well aware she is my niece.’ Henry’s chest expanded further. ‘Are you hoping that she will beg me for water, now you are prevented from stealing it?’

The blank face had gone. In its place, Joshua’s lips tightened and Alice could see his knuckles grow white from the effort of keeping his hands at his sides.

‘It is something entirely other. She needs to be married,’ he said tautly. ‘At least, Alice seems to think so.’

‘And we would like her to marry with honour,’ Alice interjected.

‘Ah.’ Henry was beginning to understand.

‘You have the contacts, or so Alice tells me,’ Joshua said loftily. Then, unable to maintain his indifference, the bitterness spilt out. ‘You may have contrived to exclude me from society in a most underhand fashion, but I trust you will not treat your niece as shabbily.’

‘My niece is a lady,’ Henry said deliberately. ‘As is your wife.’ Joshua’s knuckles whitened further. ‘I would naturally treat them as such, and if you are looking for a suitable match for Elizabeth, it may be that I can help.’

Alice could see the calculating look in her brother’s eyes, a look she knew from old. Most often it was accompanied by a charming smile, and Henry could be charming if it gave him advantage. He had charmed Papa into permanent indulgence from the day he was born; even their astringent mother had buckled beneath the onslaught: his concerned brow, his gentle voice, the smile which said it understood. But if you watched him carefully, and his sister always did, his eyes gave him away. Today, he appeared willing to swallow his rancour and agree to find a suitor for Elizabeth because it meant influence, and even greater influence if that suitor were from a distant branch of the family. It was a disturbing prospect but she must swallow her fear and do this for her daughter. The Fitzroys dotted any number of family trees, from the highest aristocracy to the lowest squire, and Henry was the only person likely to produce the right man.

‘That is very good news, is it not?’ She turned to Joshua, but her husband merely grunted.

‘For myself, I think it an admirable idea,’ her sister-in-law offered. ‘Elizabeth lives a secluded life, and must meet very few young men. And suitable husbands are scarce at the best of times. We would hate our niece to be reduced to marrying badly. To a man of business, for instance.’

She seemed to find comedy in the words, a spasm passing across her face and leaving her lips disagreeably twisted. Alice surprised herself by a strong desire to slap her sister-in-law, but was thankful that Joshua had stayed silent. It was a silence, though, that teetered on the edge, and she knew he dared not speak for risk of an uncontrollable rage. Still, she tried to think fairly, Louisa had said only what Joshua himself had declared a few days ago.

Henry nodded a dismissal and took his wife’s arm. He was making ready to leave when the vicar, half walking, half running along the churchyard path, arrived in their midst and put out a detaining hand. He was breathing heavily. ‘May I trouble you? Is the doctor still here?’

‘He left minutes ago,’ Henry answered abruptly. ‘What ails you, Reverend?’

The vicar was still finding it difficult to breathe and did not answer directly. ‘Then I must send for him,’ he puffed. ‘Ah, Mr Summer.’ He’d caught sight of Joshua standing in the shadow of a large gravestone. ‘You are the very man I need.’

‘I thought it was the doctor you sought.’

‘Yes, yes,’ the vicar said a trifle testily. ‘But he is one of your men, Mr Summer. Dumbrell, I think his name is. He is quite badly injured.’

‘Dumbrell injured? How can that be?’

‘He has a bust head. There has been some kind of contretemps. It’s difficult to make sense of the man’s words but it appears there has been a fight – over a dam?’ Henry stared at the vicar, disbelievingly. ‘He and his fellows, as far as I can gather, were attempting to demolish it but then a gang of men appeared and thought otherwise.’

‘But we did it, Mr Summer. In the end, we did!’ A man caked in mud, blood streaming from a large wheal across his forehead, staggered into view.

‘We did it,’ Dumbrell repeated. ‘And them bastards from Amberley – begging your pardon, ladies – they couldn’t stop us. That water is flowing neat and pretty. Your lake’ll be full in no time, gaffer.’

‘What!’ Henry was now the one who looked as though he would erupt into uncontrollable fury, while the smile on Joshua’s face spread slowly from ear to ear.

‘Good man, Dumbrell,’ he said. ‘We’ll get the doctor to you immediately.’

‘Good man?’ screamed Henry. ‘You’ll not hear the last of this, Summer. But you have heard the last of any help you might think to extract from me.’

‘You need not concern yourself, my dear chap. We find we don’t require your aid after all. My money will do the work. It saved your neck years ago and now it will buy Elizabeth a far better husband than any you might propose. Your sister may still have a weakness for her old home and think Amberley important, but in truth the place no longer matters. The Fitzroys no longer matter.’

Henry was gobbling with rage but her husband, Alice could see, was enjoying his triumph to the full. He went on remorselessly: ‘And while we’re speaking of county matters, Reverend –’ he turned to the vicar who was looking distressed and perplexed in equal measure, ‘– I feel it may be time for you to consider a change. You will be aware that mine is the premier estate in our beautiful part of Sussex. It seems only right, therefore, that I offer Summerhayes as a setting for the village fête.’

‘But—’ the vicar began.

‘I know, I know. It has always been at Amberley, but, as I say, times change. The fête has surely outgrown its origins, and though I grant you Amberley may have a faded appeal, I think such an important event in our local calendar, should be allowed a more modern stage. It is Summerhayes, after all, that has the money to make it the very best.’

The vicar tried again to speak, but was steamrollered into silence. ‘Consider for a moment!’ Joshua boomed. ‘The Summerhayes lawn is so much more spacious than Amberley’s and the gardens are in full flower. I am more than happy for the villagers to wander the entire estate if they so wish. I am certain that your parishioners would be most eager for the opportunity. What do you say?’

‘Well, yes,’ the vicar stammered. ‘It’s a most generous offer. But Mr Fitzroy—’ He broke off. Henry had turned his back on the group, and was marching down the path towards the churchyard gate, his wife stumbling to keep up with him.

‘Well?’ Joshua raised an enquiring eyebrow.

‘Thank you, Mr Summer,’ the vicar said weakly. ‘I’m happy to accept on behalf of the fête committee.’

Chapter Seven (#ulink_06bbf3dd-81d2-543e-a75e-fbbe7f131454)

June, 1914

They had spent all morning building a ramshackle shelter deep in the Wilderness and now they were unsure of what to do with it. William stood back and considered it from a distance. He had to admit it looked a little odd, a boy-made structure dropped out of nowhere into this wild place, besieged on all sides with lush plantings of every kind of foreign shrub. Behind them, drifts of bamboo masked from view the pathway that wound its way through the Wilderness. And behind the massed bamboo, row after row of tree ferns and palms, an ever-changing profusion of shades and textures. As a small boy, he’d had a particular love for the tree ferns. He would fold himself into a ball and hide beneath their long wavering fronds, then wait for Elizabeth to track him down. She would be forced to search long and hard and, when she found him, he would most often be asleep, curled into the fern’s green heart.

Oliver swished at the towering vegetation with a broken tree branch, one of the few left over from their labours. ‘Are we going to camp here or not?’ he asked moodily.

William looked uncertainly at his friend. Oliver was a boy who liked action but he wasn’t himself at all sure how wise camping would be. ‘There are all kinds of animals prowling through the Wilderness at night, you know.’

‘Don’t tell me you’ve got cold feet.’

‘How would we manage it anyway?’ he defended himself. ‘We’d have to sneak bedding from the linen cupboard. And apart from lumping it all the way down here, can you imagine how we’d get it from the house unseen?’

It was midday and the sun was directly overhead. Oliver wiped a sweaty hand over his forehead. ‘Well, we need to use it in some way. I haven’t spent the last three hours killing myself for nothing.’

He was right, William thought, it was stupid to build the shelter and then not use it, but he wished Olly would sometimes be a little less forceful. ‘Sorry,’ he mumbled.

Olly shrugged his shoulders, but when he saw William’s downcast face, his mood changed and he walked over to his friend and gave him a hug. ‘What we need first is something to drink. Then we’ll be able to think straight.’

‘I’ll run back to the kitchen and grab some lemonade,’ William said eagerly. ‘Cook won’t mind.’

‘Take care that your mother doesn’t see you then, or she’ll send you on some tedious errand.’

He thought it more than likely. He knew his mother would be looking for him. ‘I’ll have to go up to the house and see Mama, in any case. I can bring the lemonade back with me.’

‘Why? What’s happening?’

‘The doctor is there.’

‘So? What’s that to do with you?’

‘He has to listen to my heart and he’s coming this morning.’

Oliver frowned. ‘What’s wrong with your heart? You never said you were ill.’

‘I’m not. Not any more, at least. But Mama insists that Dr Daniels comes every month.’

His friend pulled a face. ‘What’s the matter with parents? Wouldn’t life be perfect without them?’

‘Pretty much,’ William agreed. ‘But I’ll get it over with – it’s only a five minute check – then I’ll sneak into the kitchen and bring some grub as well as the lemonade. We can have a proper picnic.’

‘Great idea, Wills. That’s what we’ll do with the shelter – it will be our daytime retreat. Somewhere we go when we don’t want to be found.’