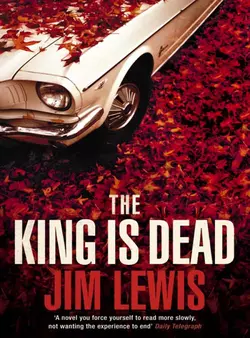

The King is Dead

Jim Lewis

A soulful, illuminating novel of love, murder and redemption, from a rising star on the American literary scene.One hot, dark night in Memphis, Walter Selby finds himself wandering alone in the parking lot outside a baseball stadium, trying to find his friend. Instead he finds his future wife, Nicole, illuminated by the headlights of a passing car. In that empty car-lot, the perfect setting for an archetypal American romance, they begin a long, lovely fall – into bed, into marriage, into parenthood, into responsibility.A generation later Walter’s son Frank, now a grown man himself, is also alone in Memphis, trying to find a trace of two parents who faded from view while he was still a child. His sister Gail is building a new family for herself on the other side of the continent, while his precious daughter Amy slips further from him with each passing year. Frank’s life seems to be racing away in a flurry of wrong decisions and lost moments, with nothing to show for it. And yet if Frank’s life is anywhere, it is in his family, in these men and women, their lives and their passing. This is their story.

JIM LEWIS

THE KING IS DEAD

DEDICATION (#ulink_f63b98b4-a853-5de9-a44f-37771083f4ad)

For Philip and Karen and Dylan and Milena

CONTENTS

Cover (#u07e7a2a3-1cc1-5898-b1fe-0f6cd68a4e62)

Title Page (#uc7826a85-c981-58b2-b633-8b35c9728500)

Dedication (#uba06a4fc-ab60-5d44-ae45-105c9b62932f)

Prelude (#ua41624fb-0f5b-5327-847b-dca0f04f3955)

Part One: Shot (#u9af5bc04-141c-55b1-8ef6-534ef1c994f3)

1 (#u0294c1fc-d072-5973-82d9-a046eb907400)

2 (#u8863157f-05b6-50a2-86d4-52c3ac8458ab)

3 (#u320a3d57-960a-5df0-a0ad-8bedade0390c)

4 (#u894566af-96ca-5731-a8c7-614a93036e8a)

5 (#u88d05e35-7a2e-586d-b6b6-2a584b9fe4db)

6 (#u85539012-bffc-59c0-a932-e06d5f07d313)

7 (#ubf92fc7e-465a-5005-bc60-90e43de09927)

8 (#ucd4c4550-0290-5efa-a708-85fce3cf5a99)

9 (#u6efaed14-0b03-51fa-8ecf-cbfbe5508551)

10 (#ub4d46619-d85f-5315-862c-bfaf43611d9d)

11 (#ub51501a2-f67e-53d1-84f3-a63c195c0ea5)

12: Stay (#ub0c005b7-e2d6-5ae3-8d71-95786485213a)

13 (#u2137dba7-db57-5d3a-9604-29cb3c5b15e3)

14 (#u81603a62-dc16-5789-b297-65e5bac3fe04)

15 (#ub5fdb234-c73b-5b49-baf7-d79890d42a44)

16 (#u50b9b9cc-2a4b-5553-a74c-35e81132e213)

17 (#u845a00ed-a4b5-5712-b5dd-2c7bba9628d5)

18 (#u1e3235dd-524b-5b07-95dd-8d452ec69888)

19 (#ud9fd00da-c362-5d08-911a-358e1b3beab9)

20 (#u6c9f2d97-c944-5194-bc1c-b98dbea30b27)

21 (#uc0d6938e-411f-59f3-a93f-c4f9887b58bd)

22 (#u949aed94-6c8d-57dd-be70-74cbbf1d641f)

23: Country (#litres_trial_promo)

24 (#litres_trial_promo)

25 (#litres_trial_promo)

26 (#litres_trial_promo)

27 (#litres_trial_promo)

28 (#litres_trial_promo)

29 (#litres_trial_promo)

30 (#litres_trial_promo)

31 (#litres_trial_promo)

32 (#litres_trial_promo)

33 (#litres_trial_promo)

34 (#litres_trial_promo)

35: Casey Stengel Testifies Before the Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly (#litres_trial_promo)

36 (#litres_trial_promo)

37 (#litres_trial_promo)

38 (#litres_trial_promo)

39: A Dress Ball at the Governor’s Mansion, on the Occasion of his Reelection to a Third Term (#litres_trial_promo)

40 (#litres_trial_promo)

41 (#litres_trial_promo)

42 (#litres_trial_promo)

43 (#litres_trial_promo)

44: An Indian on Beale Street (#litres_trial_promo)

45 (#litres_trial_promo)

46 (#litres_trial_promo)

47: Speech for Walter Selby: Draft (#litres_trial_promo)

48 (#litres_trial_promo)

49 (#litres_trial_promo)

The Brushy Mountain Letters (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: Stay (#litres_trial_promo)

Pied Beauty (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#litres_trial_promo)

2: Ten Percent of Nothing (#litres_trial_promo)

3 (#litres_trial_promo)

4: The Invention of Pornography (#litres_trial_promo)

5 (#litres_trial_promo)

6 (#litres_trial_promo)

7 (#litres_trial_promo)

8 (#litres_trial_promo)

9 (#litres_trial_promo)

10: Million-Dollar Bartender (#litres_trial_promo)

11 (#litres_trial_promo)

12 (#litres_trial_promo)

13 (#litres_trial_promo)

14 (#litres_trial_promo)

15 (#litres_trial_promo)

16 (#litres_trial_promo)

17: Shot (#litres_trial_promo)

18 (#litres_trial_promo)

19: The Ballad of the Little Sister (#litres_trial_promo)

20 (#litres_trial_promo)

21 (#litres_trial_promo)

22: Coyote (#litres_trial_promo)

23 (#litres_trial_promo)

24 (#litres_trial_promo)

25: Options (#litres_trial_promo)

26 (#litres_trial_promo)

27 (#litres_trial_promo)

28 (#litres_trial_promo)

29 (#litres_trial_promo)

30 (#litres_trial_promo)

31 (#litres_trial_promo)

32: Yvette (#litres_trial_promo)

33 (#litres_trial_promo)

34: The Death of Walter Selby (#litres_trial_promo)

35 (#litres_trial_promo)

36 (#litres_trial_promo)

37 (#litres_trial_promo)

38 (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PRELUDE (#ulink_c995e9a7-2276-555a-958c-b4ded177e71d)

There was a woman named Kelly Flynn. She was born in 1720 to a Dublin banker, and raised in London, where her father had been sent to service a loan from the King. At court she met and married a Belgian furrier named DeLours; together they had nine children, and six of them died, four from disease and two through misadventure. One who survived, an intrepid boy named Henry (b. 1745), cut short his schooling to join the Army and was commissioned as an officer.

The Empire was widening into the subcontinent and there was a great need for resourceful men. Henry DeLours was clever and brave, and he was sent to Calcutta; while there, he met an Englishwoman named Elizabeth, the daughter of a fellow officer. He married her, and they produced five children. One of them, a daughter named Mary (b. 1770), returned to England to attend boarding school.

During a tour of Cornwall, Mary met an older man, a printer named Samuel Crown, who admired her, courted her, and soon won her hand. They returned to London, and their children were William, Theodore, Olivia, and Georgia, each following on the last by a little over a year. It was expected that the male children would join in their father’s business, but Theodore (b. 1790) was willful and wandersome, and as soon as he came of age he sailed for America, looking to make a fortune of his own.

For a time he clerked in a law office in New York. Each evening he went home to his small, dark room and wrote to his mother, describing both the faith he held in his future and the hardships that were testing it: debt, the dismissiveness of the men for whom he worked, the desolation he felt in this new, strange city. But he was frugal by way of defense, and he soon managed to amass a small amount of cash, which he used to purchase a few acres of land in Kentucky. He planted tobacco, labored, prospered, and within a few years he’d expanded his estate to some three hundred acres and two dozen slaves; by the age of thirty he had come to sufficient prominence to run for a local judgeship, and, with the help of some casks of whiskey that he had delivered to the taverns on the eve of election day, he won.

It was 1820, and Judge Crown was unmarried. Instead, he took a Negro woman, a slave named Betsey, who served in his house. He brought her into his bed almost every night—Apollo may not forgive me but Pan assuredly will, he wrote in his journal—and soon she gave birth to a son, a light-skinned boy named Marcus (b. 1821).

When he was a child, Marcus’s mother told him that his father was a house slave from up the road, but by then he’d already heard rumors that he was sired by the man who owned him. The cook would cluck about it and shake her head; the footman would tease him in their quarters at night; but he never sought to confirm or disprove the story of his origin. He didn’t dare, still less when Theodore at last found a wife, with whom he could have children who were legal and sanctified.

One midnight Marcus ran away from Crown’s farm, toward a legendary North. In his pocket he carried eighteen dollars, a sum that his mother had pilfered, penny by penny, from the household accounts, and which she’d given to him along with instructions to find his way to Ripley, Ohio. Under darkness, Marcus ran through fragrant fields; in morning towns, on broad bright days, he purchased food by pretending to be on an errand from some nearby estate, where the Master had a sudden need for a particular cut of meat, or oranges to make a punch, or bread to serve to an unexpected guest. By afternoon he would be sleeping in the cover of a thick forest or down at the bottom of a ravine.

In a week he came to the south bank of the Ohio River, which he followed east as far as Ripley. He could see the town on the other side of the water, but he was afraid to cross to it, and he waited at the riverside four days and nights, for what he didn’t know. In order to stave off hunger pains he slept as much as he could; in his dreams he heard women’s laughter. At last he was discovered by the freeman John Parker, who ferried him across the water and sent him along the Underground Railroad, northwest to Chicago. Fifteen days after leaving his home and his family, Marcus landed in the living room of a boarding-house on the south side. Not knowing what his own surname might be, he called himself Marcus Cash, and soon he was working as a laborer on the docks of Calumet.

Judge Crown’s farm began to falter, he owed money to every merchant within fifty miles, and bill collectors came by regularly to dun him. In the summer of 1840, Crown got into an argument with a barmaid over a glass of beer; he became belligerent, he became violent, and she struck him in the temple with an ax handle. He lingered on for a delirious few days, and then he died. To help pay off the debts he’d accumulated, his wife sold the slave Betsey, Marcus Cash’s mother, to a plantation in northern Mississippi.

By and by, Marcus Cash met and married a mulatto woman named Annabelle, eleven years his senior, a widow with three boys of her own. She had long soft braided hair, she could sing as sweetly as a flute, she cocked her hip and swept back her skirts. Within a year she was pregnant with a daughter they named Lucy (b. 1843).

Lucy was fair-skinned and full of feeling, and she needed more attention than her parents had to spare. What’s more, she was so much younger than Annabelle’s three boys that they scarcely thought of her as a sister at all, and as soon as she reached adolescence each in turn made advances on her. Marcus Cash walked in on the third and administered a whipping to him; but the incident suggested a danger that might recur on any wicked day, and soon Lucy was on her way to school in Philadelphia with instructions to study charm, to keep her legs pressed together, and to pass for white as well as she could, whenever it was possible.

When the War Between the States began, the Cash men watched and waited, and as soon as colored troops were allowed to enlist they joined up. Marcus died at Milliken’s Bend, when the tip of a bayonet tore his heart in half; one of his stepsons died of gut wounds received by gunshot at Fort Pillow, another of pneumonia contracted in the mountains of West Virginia, and the third of inanition while marching through Arkansas.

By then Lucy Cash had returned to Chicago, and after Appomattox she and her mother moved south to Memphis, Tennessee. At Annabelle’s insistence they pretended to be a young white woman with her aged and loyal servant—but in truth the older woman was nearly insane. Memphis had been in Union hands since the middle of the War, but she wanted to be within defaming distance of the former Confederacy: The two of them moved into a rooming house and the girl took a job sewing for a local tailor; and every evening Annabelle Cash would venture out onto a bridge over the Mississippi, where she would spit down into the water, and let the river carry her insult down.

Years passed—ten years, fifteen years. Lucy Cash had become a spinster, while her mother died a long, slow, puzzled death. The daughter was thirty-two; it was unlikely that she would find a husband, and a child was almost impossible to conceive. The daughter was thirty-three, thirty-four. And then one summer morning Annabelle awoke with a chill, complained briefly, and died, leaving Lucy Cash alone with her inheritance.

What happened then became a legend in Memphis: Lucy Cash moved out of the rooming house and into a small but elegant place on the north side of town. She hired a cook and a handmaid, bought chandeliers for the house and dresses for herself, and began to throw parties for young women and men. Within a year she was among the city’s most prominent belles, fifteen years too old but no one seemed to care; the yellow-fever epidemics of the 70’s had killed many of the younger women who might have been her rivals, and besides, the gatherings at her home were so elegant, so lively, the hostess was so charming and so duskily pretty. And in time she had her suitors: a pale and wealthy middle-aged man with a horse farm, a young rich gadabout, the blond boy born to a prosperous merchant, and the son of a minister, named Benjamin Harkness.

Having a keen sense of the mystery of salvation, Lucy Cash married the minister’s son. Her wedding took place just a few days before her thirty-seventh birthday, and exactly 280 days later the first of her four children were born; they would be Sally Harkness (b. 1879), and then Benjamin Jr. (b. 1880), and Charles (b. 1881), and finally Katherine Anne (b. 1883). The two daughters were prolific from a young age, producing a total of eleven grandchildren for Lucy Cash, none of whom she’d see or hold; she died of tuberculosis in 1892, revealing only on her deathbed, and only to her two boys, that she was one-half Negro.

In 1899, at the age of nineteen, Benjamin Harkness, Jr., went north to work for big steel, staying briefly in Philadelphia before being sent out to San Francisco to oversee the development of supply lines from the port. It was an unruly town, and being the grandson of a minister born to the privilege of wealth, he took full advantage of the sins of the Barbary Coast. By day he shuffled papers in his Russian Hill office; at night he gave syphilis and cirrhosis a run to see which could kill him first. In the end, the waves preempted both; stumbling home from a wharfside saloon late one night, he fell into the Bay and was drowned.

Charles Harkness was a dull and dutiful man, less ambitious and less lively than his brother, but his blood survived. He finished college, married a woman named Alice, and became a wholesaler of dry goods. Around Louisville, Kentucky, where he lived, they called him Gain for the number of his offspring: Charles Jr. (b. 1904), George (b. 1905), Diana (b. 1905), John (b. 1906), Robert (b. 1906), the twins Mary and Elizabeth (b. 1908), Patrick (b. 1910), David (b. 1911), and the second twins, Emily and Irene (b. 1913).

As soon as she was old enough to leave the house, Diana went north to New York—to study art at the city’s great museums, she told her father, but in reality to play amid its prosperity. Many nights she came home to her Riverside Drive apartment giggling and trailing black feathers from her boa across the lobby; many mornings she sat on the edge of her bed and wept—in despair at her loneliness, in pity because she was lost. Later, she would marry a bad man named Selby in a lavish church wedding; six months passed and she had her first son, Donald; a year and a half afterward she divorced her husband, not telling him that she was going to have another child. It was a second boy, Walter, born in 1925 in his grandfather’s house in Louisville, but cared for by Diana, until one day in 1937 when she stepped in front of a car on West Oak Street, was struck and thrown, lived on for three more days, and then passed away.

When Walter Selby was eighteen he enlisted in the Marines and was sent to fight in the Pacific War. In 1945 he came home a hero, finished college in two years on the GI bill, and then went to law school at Vanderbilt. Afterward, he settled in Memphis, the home of his great-grandmother, where he went to work for the governor of Tennessee. He met a woman named Nicole, he loved her more than love knew how; he married her and they had two children, a boy named Frank, and a girl, four years younger, named Gail. This book is their annals, twice-told and twofold.

PART ONE SHOT (#ulink_0915f230-da71-59a2-b22f-3694caf1790c)

Dearest Father:

You asked me recently why I maintain that I am afraid of you….

—Franz Kafka, “Letter to His Father”

1 (#ulink_55393abe-f594-5fae-ae2b-1fb6742794e7)

Nicole’s hand was warm and damp. Three-thirty had come, the Governor hadn’t called—nor had anyone else—and Walter Selby had gone home lively to his wife, happy to have some time to spare before dinner. He was still thinking about work, running phrases for a speech through his head, but he wasn’t thinking hard. It was an afternoon toward the end of May, and he was enjoying the last hours of sunlight, along the street, under the shade of the pin oaks. To see his own house in the late sunlight of a spring weekday was a rare pleasure, and not one he wanted to squander.

To see his own wife. He parked in the driveway and emerged into a noiseless world; some money had bought that quiet, that still and green street. He could hear his steps on the walk, the hiss of the spring on the hinge of the outer door. He had his key in the lock and he paused to prolong the homecoming moment. These were instants he liked to savor: the border, and just across the border, where he would call Nicole’s name and then wait for her to answer, wait and wonder where her voice would come from, where she would appear. In the years since they’d married the process had taken on a formal quality, and the closer it came to ritual the more it delighted him; the smell of his own house delighted him, the weather dampening, the day-late hour, the light lengthening across the lawn, his anticipation lengthening along the front hall.

It was a Wednesday, and the Governor was back in Nashville, appearing at a hearing in the State Senate about advisory appointments; he would be strolling amiably down the aisle right about now, dressed in his thin grey penitent suit, a half smile on his face while he shook alike the hands of men he enjoyed and men he despised. Then he would take to his table, sit down slowly, and drop a tablet of bicarb into his water glass to distract his interlocutors while he composed himself. The water would remain fizzing at his elbow until his remarks were done, at which point he would stand up, take the glass and down its contents quickly, and then stroll out of the room again, smiling again, shaking hands, whispering.

The Selby house was quiet. Frank and the baby would be in the park with Josephine, the nanny they’d hired soon after Gail was born. This was Nicole’s own time, the part of the day when she could do what she liked, and Walter seldom interrupted her with so much as a phone call. There was some mystery in every marriage, or else there was no material left for later intimacies—for the hours after the children had been put to bed, to save and to spend, repairing the ragged forward edge of their affairs. Away from others, away from work, toward the night.

He stepped inside and called her name. There was a long silence, and he began to wonder if she was in the backyard, so he headed through the house. Along the way the light stepped down into the darkness of the living room where the blinds were drawn, up a notch in the rear hallway, and then up again into the illumination of the kitchen, which, with its south-facing windows, its formica and its reflecting metal, was as bright as a room could be. He stood there, blinking, then he turned and started back into the living room and saw her standing in the doorway, with a look on her face that he couldn’t quite describe: surprise, the satisfactions of a day, and worry or a question. She smiled a little. You’re home early, she said.

Short day, he said. She was wearing black slacks and a simple blue sweater; her hair was down, and once again he was struck. The man who first burned clay to make china: Wasn’t this what he was after? This face, in age? He put his briefcase down on the kitchen table and crossed the room to her, taking her shoulders in his hands. How beautiful, even on a bright, unglamorous afternoon; her cheeks were slightly flushed, her pupils were dilated, her lower lip hung slightly on the flesh. He hugged her; her nipples, half hard, pressed against the upper edge of his abdomen. He stepped back and looked at her from arm’s distance.

What is it? she asked.

I was just about to ask you the same thing, he said. What is it?

Nothing. What do you mean?

He shrugged. Nothing, he said. He drew her toward him again, leaned down and kissed her cheek. Neither of them smiled. He reached for her hand, a gesture he had made a thousand times before: he loved the feel of her palm against his—soft, cool, and dry—how her fingers would begin to tremble when the contact, plain at first, quickly grew awkward and unnatural, and then settled again into something comfortable, as each of them abandoned the tiny flickers of will that made their fingers clench, and peace was achieved for two. It was very much like marriage itself, he thought, where some small part of one’s self was deliberately, happily, allowed to die. But that afternoon her palm was damp—slightly hot, and slightly damp—and small and subtle though the difference was, it bothered him. He felt a clinging sensation, moist and cloying; it was like putting on a still-wet bathing suit, and he disengaged his hand from hers and rubbed his palm, slowly and almost unconsciously, against the hip of his trousers, and then bade her good-bye for a time so he could shake off the office day.

He was upstairs changing into home clothes when the children came back from the park; he could hear them burst through the door, hear Frank boasting loudly about a game. I hid in the sandbox! he said. All the way down and in, and they couldn’t find me, no matter how hard they tried. Not even Josephine could find me, could you?

No, I couldn’t, said Josephine. And I looked and I looked.

And then finally I had to come out and show them where I was, or they never would have found me, ever.—Daddy!

Walter was coming down the stairs, watching the tableau below him: Nicole had taken the baby from Josephine; Frank was struggling to get out of his muddy clothes. In the hallway? said his father. We don’t get undressed in the hallway. Frank. Come on, now. Son. Frank.

The boy said, No one could find me!

I heard, said Walter. Now go around back to the porch and take your clothes off there. And then you can tell me all about it.

Later, Walter drove Josephine home to South Memphis, his big brand-new blue Impala gliding down the streets, passing into the colored part of town, with its neat little houses set a short way back from broken sidewalks. Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Someday, he thought. And when Someday comes, what happens? He knew very little about the woman on the seat beside him, now holding her glossy black purse tight against her middle. She was good to his children; she had several of her own, all of them now grown. She had a husband at home who worked hard for a paycheck that always seemed to fall a little bit short of the week’s expenses. How big was their bed? And how well did they sleep? No better, no worse, this year or a hundred years ago; because bed was where the world reached its level, the one place where all the efforts of the State—his efforts, his State—came to nothing. This Negro woman beside him, the room she was traveling toward, the man she would meet there: When the blinds were drawn and the lights turned off, and she lay down beside her husband, the lying-down would exist in its long kindness, no matter what was done to help them or to cause them to die. Then was all work futile? He pulled up to the curb before her house and turned in his seat to face her. How are you doing? he asked.

Well, Frankie’s reading better …

No, I mean you. How are you and your husband doing? He couldn’t remember the man’s name.

Josephine shrugged. We’re getting by, she said … And she hesitated, waiting for him to say something else, then looked over and found him gazing at her, his expression split between the half smile on his lips and the darkness in his eyes. She didn’t want to know what he was thinking, so she made her good-bye and stepped out of the car, leaving Walter to nod and say, See you tomorrow, and pull away from the curb.

Promptly at seven, the family Selby sat down to dinner, but Walter was distracted, hardly listening to Frank as he recounted his boy’s day. Throughout the hour he could feel the sensation of Nicole’s nipples against his chest. Well, she wasn’t feeding Gail anymore, was she? Was it a thought, then, that had gotten into her and then started out again? He could feel her hand on his; the sensation had somehow stuck to his palm and wouldn’t dissipate. He felt it, beneath the skin and below the veins, behind the bones, between the nerves.

Little Frank didn’t want his food, he said something about the food, he complained about the food. I don’t like this. Mommy? he said, his gaze wandering off to one side. He really needed to learn to look people in the eye, thought Walter, if he was ever going to get the things he wanted.—Can I have something else? said Frank. Please? Can I? Please, please, please? He pushed his rice around his plate a little bit with his fork and then slumped down in his chair, his mouth set against any obstacle to his appetite.

Nicole was talking to the boy, but Walter wasn’t listening; he was trying to follow a rustling in the rearmost hollow of his mind. She looked at him with wide eyes. Could you help me? she said. Could you help me with this?

Frank, do what your mother says, said Walter gently, looking at her rather than the boy. She returned his gaze with a questioning and concerned expression, and the boy was looking at both of them. Gail began to cry and Nicole reached for her, so suddenly and swiftly that the baby screamed. Oh, now … I’m sorry, she said softly, almost singing. I’m sorry, don’t cry.—And just like that the baby stopped. Outside, it had begun to rain, the drops picking up where the baby’s tears had left off. Everybody could hear it, each of them in the room, everyone in the city. There was no thunder, no sound of wind, only the piano splash of the rain and the smell of wet leaves. Can I have a hot dog? said Frank.

Shhh, said Walter. And then pointlessly: It’s raining.

Nicole was still for a moment, and then she spoke to the boy in a whisper. Only if you promise to eat it all. All of it, she said. Frank promised, so she rose from the table and went to the kitchen. Walter watched her go.

After the meal he helped her with the washing up while the boy sat with his little sister; they stood side by side before the sink, but aside from an occasional accidental brush against her hip, or a mutual grazing of fingertips as he handed her a plate, he didn’t touch her. He didn’t watch her undress that night before bed, or cup her shoulder and smell her neck as she fell asleep beside him, slowly passing him into dreams. He lay awake for a long time, his arms stretched behind his head, while he pondered the prodigal inching of her blood, and the damp heat of her hand.

2 (#ulink_aff8bde2-4602-588e-862f-55dd82c8c8dc)

One hot night nine years previously, Walter Selby had found himself alone in the parking lot outside of a baseball stadium, a vast concrete pool set in acres of asphalt down by the river. The game was done and the crowds were leaving but he’d become separated from his companion, a pyknic reporter from the Press-Scimitar, in a ruckus that had begun when an elderly woman suddenly struck her cane down on the head of a passing teenager. Now he was wandering between and among the parked cars, trying to find his man. Thirty minutes had passed since the last out had been made, and still the crowds were milling. Every so often the headlights on an exiting car would swing by, causing shadows to wheel across the way; he wasn’t sure which gate he and the reporter had used to enter the stadium, earlier in the evening, still less where they’d parked the reporter’s car. And the lights, and the groups of ghosts, marked only by their voices, which passed him in the summer darkness.

There, about thirty yards away, stood a rounded figure, much like the rounded figure he had lost. The man was standing in silhouette against the downward raking light of a stanchion; Walter started that way, but as he approached the figure turned, smiling at a passing woman with a mouth full of gold, and it was another man, no one he knew. He stopped again and sighed. A car went by, boys and girls hanging out the open windows and cheering loudly.

The woman, a woman-shadow, was coming his way. She came closer and closer, until she was within touching distance; then she stopped and looked up at him, though her face was still hidden in the shadows. Well, said the woman, shaking her head. I can’t find mine. You can’t find yours, either, can you?

He said nothing, because he could think of nothing to say. An old sedan approached them, its lights illuminating her for just a moment; she had dark hair and pale skin, and fine, taut features, and she was about to smile, but the car passed and her amusement was given into the darkness again, leaving him with the impression that he’d barely missed seeing something uncommon, a notion nudged a little further on by a trace of her perfume, loosened by the passing car from the kingdom beneath her clothes. He hesitated; she was still smiling in the night. At length he said, No. I was right behind him, but we got separated coming out.

The moon was half round; occasionally its shine would be slowly occluded and then revealed by a night cloud, and the slow shuttering of the moonlight added to the woman’s superlunar appeal. I had some friends here, she said solemnly. They could be anywhere. I don’t even know how I lost them. She spoke quickly and cleanly, with a kind of confidence that she might have learned from the movies. For that matter, she continued, I don’t really know where I am. I came along because I didn’t want to sit home. She made a wry face with such force that he could feel it in the darkness.

You’re in Memphis, Tennessee, said Walter. Where the lost can hardly be distinguished from the found.

She started at the sharpness of the sentiment and then settled. I think you’re right, she said. I think you’re right. I’ll tell you what, then: You look for my friends, and I’ll look for yours. With that she took him by the arm and began to walk him in the same direction from which she’d come. Now, don’t tell me your name, she said. But tell me what your friends look like.

My friend … He had almost forgotten his friend altogether, and now he could hardly picture the man. There’s just one, a little round fellow. I don’t know. He looks like everybody else, only a bit more so. And yours? If I’m going to look for yours, I’m going to have to know.

Oh, she said. I lied about that. I don’t really have any friends here.

Came all by yourself, did you? Halfway through the sentence it occurred to him that she might be telling the truth, however improbable it may have been, and he pitched the tone of the last words down, so she could take them for sympathy or take them for mockery, either way if she wanted.

Yes, she said sadly, protruding her lower lip in a facetious sulk. No friends. Oh, well. Who needs friends? All of these people.—She stopped in her tracks and gestured around the parking lot and then widened her eyes at him. And only you are gallant enough to help me. No, she said again. Which, after all, means you’re going to have to take me home.

I have no way to get home myself, he reminded her.

Well then, we’d better find who we’re looking for or we’ll have to walk, she said.

They began to wander this way and that, they stopped to let a honking car pass, and he stole another look at her in the ruby glow of its taillights. Then they were walking again. There was something quick and supple about her stride, as she effortlessly adjusted her pace to match his. In time they came to the edge of the lot; there was a field of tall grass, and in the distance they could see the lights of cars gliding slowly along the access road. Hm, she said. This may take all night.—All right, she said, grabbing his arm a little tighter, turning him back toward the stadium. New rules: My name is Nicole Lattimore.

I’m Walter Selby, said Walter Selby. She smiled again, just as they emerged from the shadows, and this time he could see her face whole and happy, her pale blue skin and perfect countenance, and the grin set within it, so broad that her lower teeth showed like an animal’s—a figure of joy and absolute appetite, world-conquering, generous and overflowing, and so powerful upon her face that she squinted as if she too was blinded by it. Overhead there was an airplane climbing the sky, moving upward, outward from the surface of their beautiful blue-black globe. By his side there was this flawless creature, smiling and announcing her name, and he knew what he wanted.

—Stoney, she said loudly. Stoney! In the near distance a tall dark figure was loading something into the back of a sedan; the man turned at the sound of her voice, ducking his head as if it would help him see farther across the night. Nicole? Then they were at the car and all the doors were opening at once, and they were surrounded by five men, the youthful products of reason, peace, and prosperity. Oh my, said Nicole. I don’t know how I got lost, but I’ve been looking for you for almost half an hour now. This is Walter: he’s been helping me find you.

Hello Walter, said one of the men, speaking for all of them.

He’s lost also. Maybe we should give him a ride. She turned to him. Where are you going? He gave one last glance around the parking lot, now mostly empty. I suppose I should probably wait here a little while longer, he said.

No, no, she said. We can give you a ride, we can take you home. It’s the easiest thing in the world. Walter, this is George. He’s driving, and you have nothing to worry about.

They piled into the car, a big black Ford: Walter, Nicole, and two other men in the backseat, three more up front. Well, Nicole said to no one in particular, I was really worried. I was really worried, even with Walter here, and even though he was so nice. I thought I was never going to see you again, ever. With that she fell silent, but Walter listened very hard for her thoughts. He was thirty-three then, and she was only twenty-one.

To his other side there was a slight pale boy named Peter, who began to speak. You know, George, he said to the man at the wheel. You are the only man in Memphis who knows exactly where he’s going.—The car bounced over a rut in the road, and Nicole fell against Walter, her slight weight briefly lingering at his shoulder before she righted herself again. Peter continued. Your name’s Walter, is it?

Walter nodded.

Tell us about yourself, Walter.

Peter … said Nicole.

No, no, Peter went on. I’m curious. I mean, what do you do? Aside from rescuing lost women in parking lots.

That’s not enough? said Walter. My God, man. The training alone: months in the wastelands of the Arctic, years studying female physiognomy, perfecting the Reassuring Smile, the Unflappable Calm. This suit, for example: Do you think I simply fell into it this morning? Oh, no, my friend. It’s the result of decades—decades, I say—of research into color science … the psychology of texture … the evolution of animal skins. Ah, you know, John Thomas Scopes was one of ours.

The car was quiet, Peter’s wit had been broken by the time Walter had finished his second sentence, and only Nicole was smiling. Hers was the discovery: let the boys be less smug for it.

I work for the Governor, said Walter. I’m a speechwriter, an aide.

Again there was silence, and then Peter spoke again. The Governor, is that right? Tell me this, because I’ve been wondering. Has he met the newly crowned Queen yet?

The Queen? said Walter.

Elizabeth the Second. I wonder if she’ll ever come to visit us, said Peter wistfully. Well, never mind, we have our own Queen. We have our Queen right here. He reached across Walter’s legs and touched Nicole’s knee, a gesture, it seemed, as much to her silence as to the girl herself. Then he went back to staring out the window and making fun of George’s driving. The others began to go over the baseball game, making jokes, telling tales. When they got onto plays they had seen, fantastic and legendary moments, Walter spoke up.—I saw a triple play once, he said. This was in the minor leagues, though. In San Diego, while I was stationed there.

Stationed? The other man in the backseat lifted his head and leaned forward so he could crane around and look at Walter. Stationed, as in the Army? They were too young to have fought in the War, or even to remember it very well.

Marines, he said. He could feel a change of consciousness in the girl beside him, a soft click as she came a little bit more alive.

A thin-faced, red-lipped boy in the front seat turned. There were tears of excitement in his eyes. Selby, he said. Isn’t that right? Corporal Walter Selby. I knew I recognized you.

What’s that? said George, peering up at Walter through the rearview mirror.

Isn’t that right? said the thin boy again.

Yes, said Walter.

You came to my school to give a talk, about five, six years ago.—Walter frowned, not from forgetfulness but merely to disavow any vanity, but the thin boy misunderstood. Oh, you probably don’t remember, he said, as if remembering were a weakness.

Eddy remembers everything, said a weary man sitting beside Walter, who until then had said nothing at all.

You were awarded the Navy Cross, said Eddy. Yeah. For distinguished something, valor and bravery or something. Boy, you stood up there …

What’s the Navy Cross? said George.

A bit of ribbon, said Walter, and a bit of bronze.

Did you fight Germans?

You don’t use a navy to fight Europeans, said Peter.

Of course you do, said George. There’s a whole ocean between us. They had U-boats. They had a navy.

I fought Japanese, said Walter softly.

The car was quiet. They were passing over a bridge, the water below was pitch black and as smooth as glass, and Nicole reached over and briefly touched Walter’s arm.

Then they were at his door, and she was stepping out of the car, leaving him room to exit. Good night, you all, he said.

Five good-nights came back. He stood on the sidewalk, slightly turned away from Nicole, as if he couldn’t quite bear her brightness full on.

Thank you for taking care of me, she said.

You’re welcome, he said. It was a pleasure. Good night. He nodded gently and started up his walk, looking back at the girl when he was halfway to his door. She was standing beside the car, she smiled at him again with her effortless jubilation; then she waved good-bye. And she climbed back in, and the car drove off, leaving him there in the quiet of his neighborhood, in the center of his tiny little lawn, which stretched for miles and miles to his lighted front door.

3 (#ulink_7846e503-3536-5ea6-a000-ad1744d94ba0)

Back in the days when days were new, Nicole had met a man named John Brice. That was in Charleston, it was early in the fall, and all of her friends had thought he was strange. Yes, they said, he was handsome, lean and graceful, but he was strange. To begin with, he’d just appeared on the street one April day—Nicole had seen him standing outside the Loews in the middle of the afternoon, waiting all by himself for a matinee to begin—and then again, there he was on Broad Street a few days later. After that it was time to time; he was always alone, often with his hands thrust into his pockets. Sometimes it seemed as if he was dancing a little bit, dancing to himself as he went on his way. She’d seen him, a tall slim fellow with refined, almost feminine features and his hair combed back.

At the time she was just out of her parents’ house; an only child, imaginative and open. She’d spent two years in junior college, and then she came home again, took an apartment with a girlfriend named Emily, and started working in a women’s clothing store called Clarkson’s: some dresses, some underthings. Just a job, although she took pleasure in the details of the place, the feel of her fingers stretching over satin or the resistance of a band of elastic. Mr. Clarkson was usually at home, tending to his sick wife, so most of the time the store was hers; she even had keys to open it in the morning and close it at night, with only an hour or two toward the end of the day when he would stop by to empty the till and deposit it into the bank across the street. Otherwise, there she was, alone amid the cloth, the silks and nylons, and the ladies who came in.

This man, he must have been new in Charleston but he strode down the sidewalk as if he’d put a down payment on the whole town. That was something you noticed right away. Still, she didn’t think much of him; he was not-quite-regular and all alone, and it didn’t take much to make a young man wrong for a girl, in that city, in those days. At first she couldn’t quite tell what it was, exactly, and then it came to her: there was a slight eccentricity in the way he dressed, nothing that most people would have heeded, but she had an eye for the way a man put himself together. He would pass her on the street, wearing a pair of black dress shoes, perfectly acceptable, except that the laces were mouse-grey, and he had doubled them through the eyelets before he tied them. Was that on purpose, or couldn’t he shop for something as simple as shoelaces? One evening when she was walking home from work she saw him standing outside a florist’s in a seersucker suit, quite a nice one, actually, with narrow stripes of a deep rich blue; but it was a little bit late in the year to be wearing summer clothes, late enough that you would’ve thought he would be cold; and his belt was a few inches too long, so that the extending tongue turned and fell a few inches down over his hip. It was just the kind of thing she would notice, and she crossed the street instead of passing by him; but he turned and watched her all the way down to the end of the block, and she could feel his attention dragging on her at every step.

Then he came into Clarkson’s. It was a Tuesday, late in the morning, and he opened the door, peered in for a second, and then slipped across the threshold. He didn’t say a word, he just moved among the dresses and the blouses, along a line of girdles, back and around and back again, while she followed him from behind the counter and thought, What is this man doing? He took a little half step sideways—very gracefully—and she stood perfectly still. Then he did a little dance, maybe, a few subtle steps almost too soft to be seen at all, a slight gesture with his hip, his head cocked. He glanced up at her, studying her face, and she would have reddened before his eyes—but just then the telephone rang, she looked down at it, and he suddenly turned and left the store before she’d even had time to pick it up.

Then there was her father’s fiftieth birthday party, marked by a family gathering in their house outside of town—she remembered the weekend well and long afterward. So goes the tone of a time: not just forward over everything to come, but seeping outward too, in every direction, like wine on the figures of a carpet. She helped her mother in the kitchen, there was an aunt who got drunk at the party that evening, and wept noisily all night at something no one else had noticed and the woman herself couldn’t explain. That night Nicole slept in her old bedroom and listened to her parents in the room next door, arguing in soft voices and then, worse, giving in to that silence which had frightened her so when she was a child, and still made her uneasy. Poor father: a few years after she was born he’d contracted a fever, which was polio and paralyzed his left leg from the hip down. Poor mother: a local beauty alone with an infant, her husband quarantined and perhaps never to come home. By the time he recovered they were strangers again, the large family they’d dreamed of was not to be, he retreated into hobbled quiet, and she wore a seaside cheerfulness everywhere but on her mouth’s expression. Now Nicole listened as her mother sat heavily on the edge of the bed, and her father cracked his knuckles as if he would break his fingers right off.

The next day she was back at work, and that very afternoon John Brice appeared again. The same man, he walked around the store a little bit and then left. But she knew he was going to come back again, she knew she was going to know him, and she waited for him; a few days went by, and then right when she’d decided to stop thinking about it, he opened the door and came in. He had a look, didn’t he? Not just his expression, which was ready, but his clothes. This time he was wearing a grey double-breasted suit and a wide blue-and-grey tie, a foppish outfit, kind of high-toned, she thought, although he wore it very casually. He ambled up to the counter where she stood. Hello, was what he said.

She should have just said hello in return. Instead she fell back on her shopgirl manners. How may I help you? she asked.

He paused. I was just looking, he said, and motioned to the inventory with one long pale hand.

Anything in particular? she said

No…. He shook his head a little.

Maybe if you tell me who you’re shopping for, I can recommend something. The sun outside the windows shone down on an empty street, and she looked up and read the name of the store imprinted backward on the inside of the day-dark yellow glass.

What’s your name? he asked. She didn’t expect that, and she hesitated. It was something she didn’t want to give away, because she knew she’d never be able to get it back. Come on, now, he said, and made her feel foolish.

Nicole, she said at last. Lattimore. It was as if all the dresses and underthings were filled with silent women, watching women: were they smiling or shaking their heads? It didn’t matter anymore. It was done, really, with that. She gave him her name, and that was all he needed.

4 (#ulink_bc4114c5-a6d2-57af-ae94-c3831ec8b099)

On the third weekend after they’d met he invited her for a drive down to Sea Island and she accepted. He had a huge blue car, a Packard Coupe that he’d bought almost new a few weeks after he’d arrived in town; he came to get her at the hour they’d set, just past dawn, and parked outside her apartment building, but he didn’t ring her buzzer. She only realized he was there when she grew impatient waiting and put her head out the window to see if he was coming; then she went hurrying down to him, though she didn’t chastise him for not coming to her door. It seemed like one of his things, she could let him keep it if he wanted.

It was a long way, and chilly, and he drove fast, flying along the edge of the ocean, beside inlet and alongside islet, blue outside his window and green outside hers. On Sea Island they bought a basket lunch from a general store, then parked by the ocean and scared the seagulls off the sand with the car horn. Later, they kissed until her lips were sore and her tongue tasted just like his. They arrived back in Charleston that evening; it was too late for dinner, really, but he was hungry, so they stopped for a hamburger. She asked him what he intended to do with his life. She thought it would be a good way to begin to get to know him.

He didn’t hesitate and he didn’t look away. I’m going to be a bandleader, he said, and for a moment she couldn’t imagine what in the world he was talking about. Play the saxophone, jazz, he went on, and he held his hands up, one above the other, gripping an imaginary instrument and wiggling his fingers. Jazz, jazz, jazz. New York, Chicago, maybe Los Angeles. I’m going to be famous.

At first she thought he was joking; it had never occurred to her that a man could have such an ambition, that wealth and fame could be studied, rather than simply stumbled upon by those with improbable access to the unreal. Oh, you are? she said teasingly, and she saw him wince. I’m sure you have the talent, she added hastily, and you certainly look the part. But isn’t it difficult to break in?

Sure it is, he said. He paused. I’ve got a little luck, he admitted. My father, over in Atlanta—he has some money. He stopped again, as if he was suddenly embarrassed by the rarity of his fortune. My father is what you might call … a wealthy man. He doesn’t much approve of what I’m trying to do, but he’s willing to support me for a little while.

Then why did you come to Charleston?

My grandfather had a house here, he said. When he died, he left it to my parents, but they never use it. So I came up here to get away, to practice—you know. To get myself ready.

Ready, she thought. Odd syllables. Was she ready, herself? The more she thought about the word, the stranger it became.—And here was the waitress with the check, it was time for him to take her home.

5 (#ulink_113225f6-80cb-547e-b2bc-909899c5ea25)

Things about him that she loved: He was tender and devoted. He was funny, and though she’d never actually seen him on stage she was sure he was very good, and so dedicated that he was bound to be successful. He needed her in order to be happy, and he never hid the fact. He never hid anything: he wore all his emotions on his face—ambition, amusement, amorousness. He had that odd, faintly extravagant style, not just in his clothes but in almost everything he did, from the drink he ordered—a martini, bone dry, three green olives, on the rocks—to the language he used when he was excited. He was optimistic all the time, and negotiated the world with an ease that couldn’t be gainsaid.

Things about him that she never could be comfortable with: He spoke to her as if he were trying to coax her over a cliff. He judged the world immediately around him severely and without sympathy. He was moody. He had no other friends but her. Many things had come easily for him—money, for example, and self-confidence, and a sense of purpose—and he didn’t understand that those things didn’t come for her at all. He could be stubborn and impatient. He was more sure of his feelings for her than he should have been, and there was no reason why he might not change his mind. He was a field in which disappointment grew.

In later days they would go to the movies, and afterward he would do imitations of all the parts, the leads, the character actors, bit players, the women too, his voice cracking comically as he reached for the higher notes. Some of his impressions were startlingly accurate, and some of them were just terrible, and the worse they were the more she adored them. Then he would drive her back to her apartment, and, because she had no radio, they would sit outside her building, listening to swing while they kissed under the shadows of a tree—once for such a long time that the battery ran down, and when it was time for him to go home he couldn’t get the engine started, and he had to call out a truck to come help. After that he made sure to start the car every half hour or so, letting it idle for a few minutes while they went on with their talking, necking, talking, their raw rubbing at each other.

Oh, how much she loved that car, the shallow, intoxicating smell of its upholstery, the chrome strips—like piping on a dress—that bordered the slot where the window sat, the white cursive lettering on the dashboard and the fat round button that freed the door of the glove compartment. These were elements with which she shared her sentiment. Did he ever know? His keys hung from the ignition on a chain that passed through the center of a silver dollar, the thick disk spinning when the car shook; it was emergency money that his daddy had given him back when he first learned to drive, though when she pointed out that it might not be spendable with that hole in the middle, he just smiled as if she’d deliberately said something amusing.

He might have had some money but he had no telephone, so he would call her from a public booth in town, not always the same one; he would be standing by the railroad terminal, in the library, on a street corner. She couldn’t call him at all—she never quite knew where he was—and she grew more and more frustrated with waiting. She tried to show him but he didn’t seem to notice. He called her at home on a Thursday night at nine. I can’t talk right now, she said. Let me … she sighed. Well, I can’t call you back, can I? she said pointedly. Call me tomorrow.—And with that she hung up on him and went back to her reading, though the page in whatever it was trembled, and the letters shook themselves out of order. When he called her at work the next day, from a phone booth in a filling station, he never asked her what had kept her from him the night before. Wasn’t he curious? Didn’t he care? All that evening she was in a sullen mood: All right, she said shortly, when he suggested another movie; she sat upright in her seat in the theater, and neither stopped him nor responded when he put his hand on her arm and then slid his fingers down to her wrist, from her wrist to her knee, her knee to her thigh. He started up between her legs and still she didn’t move at all, so he withdrew.

He took her to a cocktail bar afterward; she hardly said a word the whole way there and sat across from him, rather than beside him, in the darkened booth. Are you all right? he said. He was wearing a beautiful grey shirt.

I’m fine, she said, her fingertip playing distractedly across the lip of her martini glass. She waited a moment, and then she said, I don’t think we should date anymore.

He widened his eyes and slumped back in his seat. No? he said.

I’m sorry, said Nicole. I just don’t think we should.

No? he said again, as if he was hoping that No said twice might mean Yes. Will you tell me why?

He was hurt, and whatever gratitude she might have felt for his exhibition of caring quickly gave way to guilt, so she drew back from her anger and offered him a deal. She couldn’t bear to wait by the phone, but they would be fine if he would call her regularly, at work just before noon to make plans for the evening, if plans were to be made; at home before nine if there was nothing to say but hello.

It was their first bargain, and he kept his end carefully, mornings and evenings. There was nothing romantic about the routine, not at first; it was just John calling the way he had promised he would. And then it was romantic, after all, and October turned into November.

6 (#ulink_eefbe5fc-8ab9-5ced-8b65-cae112163242)

Now tell me, because I don’t know, she said one afternoon. Where do you live? He had arrived at her door in his car again, and it had occurred to her, not for the first time, that she didn’t know where he was coming from. He seemed to prefer it that way; anyway, he never volunteered to tell her. If she had to ask, she would ask: Where do you live?

He shrugged. Up in the woods, a few miles out of town, west. She waited. It’s just a little house. He traced an invisible house in the air with his fluid hands. Up in the pines, about ten miles from anywhere. At night it’s so quiet, all you can hear is the wind and the wolves carrying on.

Is that right? she said with a smile. She wasn’t sure what to believe, but that was how she thought of him from then on: John-of-the-Pines when he was being quiet and sweet, John-of-the-Wolves when he had his long tongue in her mouth and his hands all over her. That was a world, and a town, and a tenure.

She told her parents she was dating a man, mentioning it to her mother in their garden one Saturday afternoon and counting on her to convey the news to her father. And what does he do? her mother had asked. She was wearing a sun hat that hid her eyes, but her tone of voice suggested that she was asking for an appraisal rather than an intimacy, as if being a lady was a business, too.

He’s with his father’s firm, said Nicole, quite startling herself with the ease with which she lied. Something to do with wood: forestry, lumber, paper, something like that.

He sounds very promising, said her mother, as she primped a gardenia. Your father will be pleased. When will we meet him?

Soon, said Nicole. We’ll make a date and I’ll bring him by, she promised, but somehow she never did.

One morning John Brice made his morning call from a booth outside the supermarket; he was in there, just wandering around the aisles, looking at all that food, and he decided on the spot to make her a dinner.

When?

I was thinking tonight, he said, and she sighed to herself, disappointed that he was treating an occasion she found momentous with such lightness of intent.

All right, she said. Tonight, then. Let me go home and get myself fixed up, and you can come by for me at seven.

Hot damn! he said suddenly. Dinner tonight! I’ll be by at seven.—And he hung up the phone before she could ask what she could bring.

At seven he was at her door, and as he walked her to the car he gestured at the paper bag she was carrying. What have you got?

A pie, she said. Store-bought, I’m sorry. And a bottle of wine.

He kissed her. Wine, oh, wine, he said, and kissed her again. Spodee-o-dee!

He took a county road back up behind the town, beating softly on the steering wheel to the rhythm of the song on the radio. In time he turned down a bowered lane, and she asked herself if it was so wise of her to have come along, after all. I don’t really know that much about him, she thought. Do I? He was leaning far back in the front seat with his knees almost resting on the dashboard, and he didn’t appear to be looking at the road at all; it was as if he were navigating by the treetops. Then he slowed and turned down a driveway, up under the trees they went, and he watched with her as his headlights swung across the front of a little gingerbread house standing in a clearing.

You don’t get to see too many houses like this anymore, he said. Not really. This was a bootlegger’s house, going back to the last century. This was where they stored the whiskey, up here in the woods. Casks of it. That’s how my granddaddy got rich. He exited his side of the car, and she stayed in her seat until he came around and opened her door, not a courtesy she would ordinarily have waited on, but it seemed appropriate to the occasion. There was a wide wind coming across the hills; it was chilly, and she shivered. He put his arm around her and began to walk her to the door. He left the place to my folks, he continued, but they don’t want to be reminded that there’s some dirty money mixed in with their nice clean cash, so they stay in Atlanta. I always knew it was here, though, and when I had to leave Georgia, I knew I was going to spend some time here.

Why did you have to leave? she said, and she stopped, as if she was going to refuse to walk any farther if there was something wrong with his answer.

He turned, serious as a funeral: They were looking for me. Because …—she stared—I shot a man in Reno.

You did what?

Now he was singing, in a hillbilly voice: Just to watch him die….

She started to back toward the car. John.

I’m joking. I’m just joking. Nicole. It’s a song, one of those new songs, he said. I didn’t have to leave. Not like that, like you’re thinking. I wasn’t in trouble. I just had to leave because I didn’t want to be there anymore.

John Brice’s house smelled of the walnut boards they’d used to build it; she noticed that as soon as they walked inside. There were four rooms: kitchen, dining room, sitting room, study. This is my place, he said. The light from the lamps was as dim as an old man’s eyesight, and the pictures on the wall were dark and dignified. It wasn’t the sort of house she expected, and then she remembered that he wasn’t the one who had decorated it; the only sign that it was his at all was a saxophone balanced against a music stand in one corner. The rest was rather gloomy. It needed a lighter touch, something a woman would do, and she allowed herself to imagine for a moment…. There’s a big old cellar that’s empty, he said, and a bedroom tucked up under the eaves, upstairs. You can’t tell it’s there from the outside, in front, but there’s a window in back. She nodded; what was this talk of bedrooms, anyway? He took her jacket and hung it on a peg on the wall.

She looked at the saxophone again. Will you play me something? she said.

Maybe later, he said, taking her by the hand and leading her into the kitchen, where he hugged her so hard she cried out and then laughed. I’ll play you something I wrote for you.

Dinner was good, she didn’t know any boys who could cook, but John Brice got together a meal, broiled some steaks with a dry rub made from his grandfather’s recipe, and made mashed potatoes. Now the wine was done. Standing in the quiet kitchen, the dishes piled in the sink, the only light coming from a fixture over the stove, and she wanted to say something to him about how lovely the evening had been, he was before her, beside her, and—how did it happen?—he was behind her, and there was a hole in the back of her that she couldn’t see and couldn’t close. It ran all the way up to her heart, which was pounding and pounding, in anticipation of being crushed. Shhh, she said, and there was quiet. She didn’t want to miss anything; she wanted to feel every fluttering of experience. Don’t worry, he said, but she wasn’t worrying.

There he was, groom and spouse. Come here, he said, although she was already in his arms. He put his hands under her blouse, resting them gently on the warm flesh of her hip. How close did he mean to come? He kissed her, more than once but less than many times; then he led her by the hand into the living room and laid her on the couch. His hand was on her breast and she tipped her head back a little bit, a reflex; she didn’t know what she wanted. He murmured something, she couldn’t make out what, and she couldn’t tell whether he wasn’t talking or she couldn’t hear. She looked all the way across the room to a window. The moon had risen away, climbing up so far that it had disappeared, there was nothing but blackness where the sky would be, and all she could sense was the smell of John’s arms, the wetness of his tongue, his murmuring beneath the noise she made when the boundary broke, the tears and gore leaking out of her, making a mess, and the wind in the trees outside.

She had helped him rend her from the word Miss. What a good sport: so lovely: what a lustful thing. She wasn’t sorry to see it happen, but she lay awake for some hours afterward, gazing on her rags and tatters, until she roused him from his sleep and insisted he take her home before morning. By the time they got back to her house the sun was nearly up and she was exhausted, really so tired she could barely make it the last few steps to the door.

The next day she found that there was little she remembered about those final aspects of the night before: the smell of walnuts, looking at herself in the bathroom mirror, and then taking a cool wet washcloth to her bloody thighs and carefully rinsing it clean in the sink when she was done. He said he had a song for her, but he hadn’t had a chance to play it, had he? She remembered his last kiss of the night, which penetrated past her mouth all the way into her skull.

7 (#ulink_6af961e2-699f-55c7-84b9-5fb67b88ce38)

Emily in the living room of their small apartment on Chapel Street, sipping at a gin and tonic in the dust-amber heat of a Saturday evening. Emily, who worked as an assistant at a furniture importing firm and had lunchtime trysts with the married man who managed the place. She was wearing one of his dress shirts, open to her navel, and she was giggling as Nicole described the night before. Then she resumed her usual air of lassitude. How bad was it?

It wasn’t bad at all, said Nicole. Which is not to say that I actually enjoyed it.

Did he enjoy it?—She took another sip of her drink. As long as he enjoyed it, darling. We do what we can.

Nicole frowned. I don’t know. I didn’t ask.

Oh, I’m sure he enjoyed it, said Emily. They usually do.

Speaking of which, how did you get that shirt? said Nicole. Did you send him back to the office bare-chested?

That’s one of those secret tricks we kept women have. How to build up your wardrobe, without his wife being any the wiser. I wonder if I could write that up for one of the magazines. Tips for a Fallen Angel, by Anonymous. She sipped at her drink again. So. My little Nicole has a lover.

I suppose I do, said Nicole.

Hurrah, said Emily. Another wicked girl.

I suppose I am.

Then we’ll have each other to talk to in hell. Bring along a parasol: I hear it’s hot down there.

Well, I may pay for it on Judgment Day, but I’m going to get as much from him as I can in the meantime.

Nicole! Emily laughed.

Jezebel, if you please. Jezebel, harlot, hussy, trollop, any of those will do.

Slut, said Emily, and was immediately sorry she’d said it.

But no,—Slut, said Nicole emphatically, even as she reddened at the word, and wondered if it was right.

8 (#ulink_be2466a0-6899-5f06-b6e8-e81142299be5)

On the way home one night, John Brice confessed to a future he’d obviously worked out in detail, so much so that it was more real to him than the car he was driving and the road it was on. We’re going to go out west, we two, he said. We can go to Los Angeles, get out of here. I’m going to put together a band, get a house gig at a big fancy nightclub. Get rich, live in a house up in the hills, with a hundred rooms and picture windows that look out on the lights. We’ll go to parties every night, drive down Sunset Boulevard in a big silver convertible, we’ll know the names of all the important people, and they’ll know ours.

But the whole of his speech was an opposite to her. Everything he said, when he was in that kind of mood, told her in forfeiting terms that he wasn’t the man she had been waiting for. Because she didn’t want any of that: really, not at all. He frowned a little when she failed to answer, but he didn’t say anything more. What did he care if she was silent? His will was all he needed. How did he do that? she wondered. She sometimes thought that he wanted to kill her, or at the very least, that he didn’t care whether he killed her or not.

Over the course of the following few weeks she spent almost half her nights at his house, conscious each time that she shouldn’t be there, she was opening up for something to go wrong. At first she kept forgetting to plan ahead, and she had to wear the same clothes to Clarkson’s the next day and worry that some busybody matron would notice, and know at once what she’d been doing. Then she wised up and left a dress or two at his house; her wanton clothes, they called them. Gin bottles in the liquor cabinet, red moon in the sky, songs on the radio. She had just started to get used to it, sex and all the setup it required, she had just started to enjoy it, when he tested her reach again.

He made another dinner one night in early November, a big ham, greens, cornbread, and she had only been able to eat a little of the mountain he piled on her plate. Afterward, he stood from the table, fixed her a drink, and then began to pace. Here’s what I’m thinking, he said. I have to, if I want to do…. She didn’t give him any look that helped him. It’s time, he said. It’s past time. I’ve been here, I stayed here longer, because I wanted to be with you. And I still want to be with you, but I have to go. So I’m going to go, up to New York. And I think you should come with me.

She frowned, she didn’t think he was all that serious. New York? The words meant nothing to her. I’m not going to New York, she said. I’ve never been and I’m not ready to go now. Why do you want to do that? I don’t. What do you want to go up there for?

He said, Everything I need is up there, all the people I want to meet.

People? Meet?

Other musicians, songwriters, arrangers. I can’t stay around here forever, I’ve been here too long already, I can’t stand it. It’s time for me to go.

She thought she was everyone he’d ever want to know, and she went cold, inside and out. Well, you go to New York if you want, she said. I’m not going. You go make yourself into a big man.—She made a mockery of the last two words. If he noticed he ignored it.

I want you to come with me, he said. I’m asking you to come. Nicole. Nicole. I have enough money to keep us for a while.

She shook her head. You’re crazy. Go if you want, but I’m staying here.

She thought that was the end of it; either he would go immediately and leave her to childlike Charleston, or he would stay for a while and change his mind. But she was wrong: they talked about it all through the following days; always he said he had to go, always she said she wouldn’t, and always there was the next day, the next discussion, dissection, dissension, another day of putting off disaster.

It’ll be so easy, he said, on the drive back to his house one night.

It’s not easy at all, said Nicole. My family, my friends are here. You and I are here. She waited a moment, gazing at a cream-colored quarter moon out the window on her side of the car, but he said nothing in response, and when she looked over at him his stony face was illuminated in the glare of an oncoming car.

That was December 1st, and she felt the ends of things overhanging. Three days later he disappeared, just like that. He didn’t warn her, he didn’t explain. His calls stopped coming, and she waited, she thought it was because they’d fought. But a week went by and still no word, so she borrowed a friend’s car and drove out to his house, only to find it empty and dark. Then she realized he’d left for good and without a good-bye. He’d gone to New York.

She imagined that the city had swallowed him as soon as he set his first foot down on the sidewalk. In her head New York was hell, and he was innocent but there he was. Hell, because there were so many, many people, none of them had faces, and there was no escape, and no way for them to love each other. She couldn’t imagine what kind of experiences he might be having. She tried to picture it, but all she could see was his back as he walked down the street, because he, too, had lost his features. She worried and wept; she’d never realized she was capable of such misery.

She would be tempted to ask the women who shopped in Clarkson’s: Should a woman travel to hell in order to be with a man she loves? Seven dollars and fifty cents for a girdle. Three dollars for nylon hose, beige, package of three.

9 (#ulink_ee78abd8-b07c-5a83-bb45-7e6ababff47e)

One sunny Friday morning just after New Year’s a woman came into Clarkson’s, someone Nicole had never seen before: bleached blonde, her makeup hastily applied and unflattering, no smile and no gaze. Maybe the woman was thirty, maybe thirty-five; she shopped a little bit, she looked around at this and that. She took a dress down from its stand and turned it forward and backward to get a better look. There’s a fitting room in back, if you’d like to try that on, said Nicole. The woman merely nodded, replaced the dress, and turned away to another part of the store, where there were lacy underthings. Just about then Nicole realized they were running out of the tissue paper that they kept below the counter, so she went into the back room to get some more. When she returned the woman was gone, arid it was only an hour later, when she was going through the store, primping the stacks, that she discovered an entire shelf full of hosiery missing, and she was halfway to the stockroom for replacements before she realized that the woman must have stolen them. How very strange, the more so since they were different sizes, and so she couldn’t possibly have had any use for them all herself. Well, thought Nicole, I’ll have to tell Mr. Clarkson, and he won’t be happy about it. He can’t really blame me, though. Who would have thought a woman was a thief? It made her sad to think about it, and sadder still to think she had no one to share the story with.

10 (#ulink_2327594f-62ff-5869-9ab0-26a69c5c7fea)

Nicole put a sign on the door of Clarkson’s that said:

CLOSED FOR LUNCH OPEN AGAIN AT 2:00

She locked the front door and stepped out on the sidewalk. It was chilly, and the sky was shallow and grey as ashes. She hurried the few blocks home. In her mailbox there was a small lilac envelope with the address of a high school friend’s parents engraved on the back flap.—And a letter from New York City. She opened the lilac envelope immediately; it was an invitation to the girl’s wedding, and she put it down on her kitchen table and sat suddenly. Well, weren’t they all grown up? She had no way of explaining how such a thing could be happening.

She went to a tea shop for lunch; she ordered, she ate, she wondered where the new year was taking her. Back at the store, an empty afternoon, she opened John’s letter, accidentally tearing right through the return address, which was just as well: she didn’t want to know exactly where he was.

Dear Nicole:

Please forgive me because I don’t write very well. I’m sorry I left without saying good-bye. I didn’t know what to say. I love you very much but I had to leave Charleston. I wanted you to come with me, but I did not want to fight about it anymore.

New York is even bigger than I thought it would be. Yesterday I saw Robert Mitchum right on the street. I am playing with some fellows, and they are very good. I hope that someday I will see you again. Please do not be angry with me. Write to me at the address on the envelope if you want to.

Love,

John

She’d never seen his handwriting before; it was crude, unschooled, a cursive script with wide, fat loops, as if he were roping down each word. She could imagine him buying the paper at some corner store, reaching into the pocket of one of his suits for his billfold, with that funny expression he got on his face whenever he spent some money, his eyebrows raised as if the transaction was a surprise to him and he was a little bit worried that he’d get it all wrong, somehow; she could picture him sitting at his desk in some cheap hotel, brown eyes swimming; she could see him putting the letter in a mailbox and then disappearing into the crowds on Broadway; and then she couldn’t see him anymore. She folded the letter slowly, put it back in its envelope and put the envelope back in her purse. Through the plate glass in the front of the store she could see an old man in shirtsleeves and a white panama hat, shuffling off to the left.

John Brice had ventured to Babylon with his faithful genius about him; and if that was where he wanted to be, what was hers to add? He didn’t love her, she thought. He didn’t mean it; either he was living in a dream or he was lying. So sooner or later he would have grown tired of her and he would have started to hate her, and she’d be alone and not so young anymore, and stranded in New York City.

The door opened and a woman came in, and without breaking her gaze through the window, Nicole said, May I help you?

Darling, it looks like you could use a little help yourself, said Emily. I was going to invite you to lunch, on me.

Nicole blinked in surprise. I just ate, she said.

You look like something just ate you.

I got a letter, you know—she gestured—from John in New York.

He still trying to get you to come up there with him?

Nicole shook her head. No, she said. He’s gone.

Then forget about him, said Emily. You’re twenty years old. There’ll be another, believe me. There’ll be another.

But Nicole wasn’t sure there’d be another at all. What if he was the only one, ever? For a few days she thought about writing him back, but she couldn’t have told him anything; it was a madness that started anew each evening, a paralysis in her blood that prevented her from sending so much as a note to him. It was too much for her: the weeks of wandering around with a blank look on her face, an entire symposium she conducted all by herself. Answers, another idea, another question. She never did decide what to say to him, where to start, what good any of it would do, so she never wrote back to him at all.

11 (#ulink_aa95fb90-a008-51be-8115-32b54c21a882)

One morning in early March, Mrs. Murphy with the red hair and white gloves came gliding into Clarkson’s, accompanying her fourteen-year-old daughter for her first brassiere, in preparation for her journey to the city’s most exclusive finishing school. She got to chatting with Nicole while the girl was in the dressing room. Now, love, a woman like you can’t spend the rest of her life working in a place like this, said Mrs. Murphy. Mr. Murphy’s cousin works for a radio station in Memphis, and he was just telling us how they were looking for a girl to work there, someone to help around the office. Maybe you should call him, Howard Murphy. He’s in the directory.—Oh, look, and here’s my baby all dressed up like a woman. Lift it up a little, honey. In front. In front, just a little. The girl watched as her mother slipped her thumbs under the top edge of her own cups and tugged them gently upward. The girl did the same.—There you go. Mrs. Murphy turned back to Nicole and unsnapped her little black clutch. We’ll take three, she said with a small smile, and drew out a carefully folded bill with her fingertips.