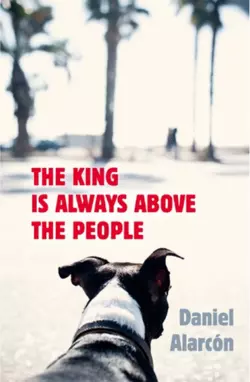

The King Is Always Above the People

Daniel Alarcon

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 930.44 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Longlisted for the National Book Award for FictionAn unforgettable collection of stories from Daniel Alarcón, one of the New Yorker’s 20 best writers under 40, and one of the best storytellers of our time.Migration. Betrayal. Family secrets. Doomed love. Uncertain futures. In Daniel Alarcón’s hands, these are transformed into deeply human stories with high stakes.In ‘The Thousands’, people are on the move and forging new paths; hope and heartbreak abound. A man deals with the fallout of his blind relatives′ mysterious deaths and his father′s mental breakdown and incarceration in ‘The Bridge’. A gang member discovers a way to forgiveness and redemption through the haze of violence and trauma in ‘The Ballad of Rocky Rontal’. And in the tour de force novella, ‘The Auroras’, a man severs himself from his old life and seeks to make a new one in a new city, only to find himself seduced and controlled by a powerful woman.Richly drawn, full of unforgettable characters, The King is Always Above the People reveals experiences both unsettling and unknown, and yet eerily familiar in this new world.