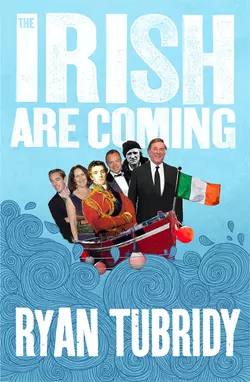

The Irish Are Coming

Ryan Tubridy

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Историческая литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 191.96 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In the sequel to his bestselling JFK in Ireland, the Emerald Isle’s favourite son delves into his country’s past to celebrate the Irish people who through their skills and endeavours helped make the British Isles great.In ‘The Irish Are Coming’ Ryan Tubridy takes a journey into Ireland’s past to unearth the many amazing, and altogether fascinating, contributions the Irish have made to everyday British life; whether it be making us laugh (Graham Norton), thrilling us with their acting (Peter O’Toole), or dazzling us with their audacious adventuring (Earnest Shackleton).Just as Stuart Maconie has celebrated all that is great about his North of England roots in ‘Pies and Prejudice’, so the delightfully entertaining Ryan Tubridy makes a passionate case for the magnificent contribution Ireland has made to its nearest neighbour.