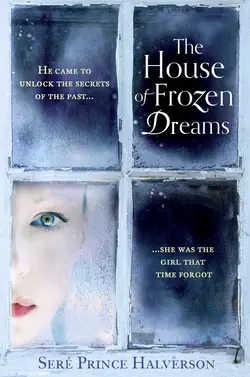

The House of Frozen Dreams

Seré Prince Halverson

Set in the stunning, eerie Alaskan mountains, this is a love story you will never forget.Step into the home that lay empty for decades…After a family tragedy, the old Alaskan homestead lay abandoned for two decades, until the one person who need it most came looking. What Kache found was more than a house full of old memories and buried secrets: he found Nadia, who had been hiding from the world, unseen, for ten years.Held captive by a past too painful or too dangerous to face, they must now break free from what binds them in place – and face the ghosts that have never stopped haunting them.Step into the house of frozen dreams…

Copyright (#uec953bec-07ae-5dad-9e8f-52d0caf8a62b)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Harper 2015

Copyright © Seré Prince Halverson 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Irene Lamprakou/Trevillon Images (girl); Plainpicture/Pictorium (window)

Seré Prince Halverson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007438945

Ebook Edition © January 2015 ISBN: 9780007438952

Version: 2014-10-29

Dedication (#uec953bec-07ae-5dad-9e8f-52d0caf8a62b)

For Daniel, Michael, Karli and Taylor

Contents

Cover (#u16c35891-953b-5bc1-bc82-a38ed8ee883a)

Title Page (#u51830047-a226-52dc-8586-6d2e8de28f94)

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: Breakup 2005

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Part Two: Land of the Midnight Sun and the Prodigal Son 2005

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Part Three: The Fall 2005

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Part Four: Winter Tracks 2005–2006

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-One

Chapter Sixty-Two

Part Five: Breakup 2006

Chapter Sixty-Three

Chapter Sixty-Four

Chapter Sixty-Five

Chapter Sixty-Six

Chapter Sixty-Seven

Chapter Sixty-Eight

Chapter Sixty-Nine

Chapter Seventy

Chapter Seventy-One

Acknowledgements

Q&A with Seré Prince Halverson

About the Author

Also by Author

About the Publisher

PART ONE (#uec953bec-07ae-5dad-9e8f-52d0caf8a62b)

ONE (#uec953bec-07ae-5dad-9e8f-52d0caf8a62b)

This: her nightly ritual. She took the knife from the shelf to carve a single line in the log-planked stairwell that led from the kitchen to the root cellar. She’d carved them in groups of four one-inch vertical lines bisected with a horizontal line. So many of them now, covering most of the wall. They might be seen as clusters of crosses, but to her they were not reminders of death and sacrifice but evidence of her own existence.

There were other left-behind carvings too, in the doorjamb on the landing at the top of the stairs. These notches marked the heights of growing children, two in the Forties and Fifties, and two in the Seventies and Eighties, one of whom had grown quite tall. She saw the mother standing on a footstool, trying to reach the top of her son’s head to first mark the wood with pencil, while he stood on tiptoes, trying to appear even taller. She almost heard their teasing, their laughing. Almost.

Six stairs down, she dug the tip of the knife into the wall. The nightly ritual was important. While she no longer lived according to endless rules and regulations, with all those objects and gestures and chants, she did not want her days flowing like water with no end or beginning; shapeless, unmarked. So she read every night, book after book, first in the order that they lined the shelves, turning them upside down when she finished reading and then right-side up for the second read and so forth, now returning to her favorites again and again. And during the day she did chores—foraging, launching and checking fishing nets, setting and checking traps, gardening, tending house, feeding chickens and goats, canning and brining and smoking—all in a certain order, varying only according to the needs of the season. Her days always began with a cold-nose nudge from the dog and not one, but two enthusiastic licks of her hand as if to say not just good morning, but Good Morning! Good Morning!

Then, there were the mornings when she ignored the dog and unlatched the kitchen door so he could let himself out while she returned to bed to stay, dark mornings that led to dark days and weeks. During those times, only under piles of blankets did she feel substantial enough not to drift away; they kept her weighted down and a part of the world. But eventually her dog’s persistence and her own strong will would win over and she’d drag herself up from the thick bog and go back to her chores and her books, carving the missing days into the wall so they did not escape entirely.

It was surprising, what a human being could become accustomed to—a lone human being, miles and years from any other human being. She balanced two more logs and a chunk of coal in the woodstove, and with the dog following her, crossed the room in the left-behind slippers, which had, over time, taken on the shape of her own feet. She’d been careful to keep things as she’d found them, but those slippers were another way she’d made her mark, left her footprint, insignificant as it might be.

Now she sat in the worn checkered chair and picked up one of the yellowed magazines from 1985. Across the cover, Cosmetic Surgery, The Quest for New Faces and Bodies—At a Price. “A new face, this would help,” she once again reminded Leo, who thumped his tail. Unlike the people in the article, she said this not because she was wrinkled (she wasn’t) or thought herself homely (she didn’t). “It would give us much freedom, yes? A different life.”

She opened the big photography book of The City by the Bay, and took in her favorite image of the red bridge they called golden, and the city beyond, as white as the mountains across this bay. So similar and yet so different. That white city held people, people, people. Here, the white mountains held snow. “And their bridge,” she told Leo, closing the book. “We could use that bridge.” He cocked his head just as she heard something scrape outside.

A branch. In her mind, she kept labeled buckets in which she let sounds drop: a Branch, a Moose, a Wolf, a Bear, a Chicken, the Wind, Falling Ice, and on and on. Leo’s ears perked, but he didn’t get up. He too was used to the varied scuttlings of the wilderness. She drew the afghan around her shoulders and opened a novel to the page marked with a pressed forget-me-not.

Yes, she knew a certain comfort here—companionship, even. How could she be truly alone when, outside her door, nature kept noisy company and at her feet lay a dog such as Leo? Then there were the books. She’d traveled inside the minds of so many men and women from across the ages. And she had such long, uninterrupted passages of time to think, to ponder every turn her mind took. For instance, there was the word loneliness and the word loveliness. In English, one mere letter apart, and in her handwriting the words looked almost identical, certainly related. This she found consoling, and sometimes even true.

But now, another sound, then many unmistakable sounds; determined footsteps coming toward the house. Leo’s ears flipped back before he plunged into sharp barking and frantic clawing. She froze. All those years practicing what she would do, but she only sat, with the book open in her trembling hands. Where did she leave the gun? In the barn? How had she grown so careless? She remembered the knife on the shelf in the stairwell and finally bolted up to grab it. She flipped off lights, took hold of Leo’s collar, tugging him from the door and up the stairs to the second floor. She pulled the window shade and it snapped up, but she yanked it back down because she couldn’t see anyone, though the moon was full. With all her strength she dragged Leo, pushing and barely wedging him under the bunk bed with her, and clamped his nose with her hand just as the loose kitchen window creaked open below. A male voice, a yelling, though she didn’t hear the words over Leo’s whining and the blood pum-pumming in her ears.

It was him, she was sure of it. Shaking, shaking, she squeezed harder on the handle of the knife and wished for the gun. But she was good with a knife, she was sure of that too.

TWO (#uec953bec-07ae-5dad-9e8f-52d0caf8a62b)

There he was, Kachemak Winkel, sitting upright, on a plane of all things, finally headed home of all places. Yes, his fingernails dented the vinyl of the armrests, and the knees of his ridiculously long legs pressed into the seat in front of him, causing the seat to vibrate. A little boy turned and peered at Kache through the crack between B3 and B4. Kache motioned to his legs with a sweep of his hand and said, “Sorry, buddy. No room.” But he knew that didn’t account for the annoying jittering.

“Afraid of flying?” the man next to him asked, peering above his reading glasses and his newspaper. He wore a tweed blazer and a hunting cap, which made him look like a studious Elmer Fudd, but with hair, which poked out around the ear flaps. “Scotch helps.”

Kache nodded thanks. He had every reason to be afraid, it being the twentieth anniversary of the plane crash. But oddly he was not afraid to fly and never had been. If God or the Universe or whoever was in charge wanted to pluck this plane from the sky and fling it into the side of a mountain in some cruel act of irony or symmetry, so be it. All the fear in the world wouldn’t make a difference. No. Kache was not afraid of flying. He was afraid of flying home. And that fear had kept him away for two decades.

He shifted in his seat, elbow now on the armrest next to the window, his finger habitually running up and down over the bump on his nose that he’d had since he was eighteen. The plane window framed the scene below, giving it that familiar, comforting screened-in quality, and through it he watched Austin, Texas become somewhere south, just another part of the Lower 48 to most Alaskans.

He had spent most of those two decades in front of a computer screen, trying to forget what he’d left behind, scrolling column after column of anesthetizing numbers, and getting promotion after promotion. Too many promotions, evidently.

After the company had laid him off six months ago, he replaced the computer screen with a TV screen. Janie encouraged him to keep looking for another job but he discovered the Discovery Channel, evidence of what he’d suspected all along: Even the world beyond the balance sheets was flat. Flat screen, forty-seven inches, plasma. That plasma became his lifeblood. So many channels. A whole network devoted to food alone. He learned how to brine a turkey, bone a turkey, smoke a turkey, high-heat roast a turkey. The same could be said of a pork roast, a leg of lamb, a prime rib of beef.

Branching out, he soon knew how to whisper to a dog, how to de-clutter his bathroom cabinets, how to flip real estate and what not to wear.

Then he came across the Do-it-Yourself network, and there he stayed. “Winkels,” his father had liked to say, long before there was a DIY network, “are Do-it-yourselfers exemplified.” Kache now, finally, knew how to do many things himself. That is, he could do them in his head, because, as Janie often reminded him, head knowledge and actual capability were two different animals. So with that disclaimer, he might say he knew how to restore an old house from the cracked foundation to the fire-hazard shingled roof—wiring, plumbing, plastering, you name it. He knew how to build a wood pergola, how to install a kitchen sink, and how to lay a slate pathway in one easy weekend. He even knew how to raise Alpacas and spin their wool into the most expensive socks on the planet. Hell, he knew how to build the spinning wheel. His father would be proud.

However.

Kache did not know how to rewind his life, how to undo the one thing that had undone him. His world was indeed flat, and he’d fallen off the edge and landed stretched out on a sofa, on pause, while the television pictures moved and the voices instructed him on everything he needed to know about everything—except how to bring his mom and his dad and Denny back from the dead.

The little boy in front of him grew bored and poked action figures through the seat crack, letting them drop to Kache’s feet. Kache retrieved them a dozen times, but then let their plastic bodies lie scattered on the floor beneath him. The boy soon laid his head on the armrest and fell asleep.

On Kache’s first plane ride, his dad had lifted him onto his lap in the pilot’s seat and explained the Cessna 180’s instruments and their functions. “Here we have the vertical speed indicator, the altimeter, the turn coordinator. What’s this one, son?” He pointed to the first numbered circle, and Kache didn’t remember any of the big words his father had just spoken.

“A clock, Daddy?” His dad laughed, then gently offered the correct names again and again until Kache got them right. It was the only memory he had of his father being so patient with him. How securely tethered to the world Kache had felt, sitting in the warm safety of his dad’s lap, zooming over land and sea.

Why had it been impossible to hop on a plane and head north, even for a visit? He tried to picture it: Aunt Snag, Grandma Lettie, and him, sitting at one end of the seemingly vast table at the homestead, empty chairs lined up. Listening to each other chew and clear throats, drumming up questions to ask each other, missing Denny’s constant joking and his father’s strong opinions on just about everything. Who would have believed he’d miss those? His mother’s calm voice, her break-open laughter so easy and frequent he could not recall her without thinking of her laugh.

So instead, once he began making decent money he’d flown Gram and Aunt Snag to Austin for visits, which provided plenty of distractions for all of them. As he drove them around, Grandma Lettie kept her eyes shut on the freeway, saying, “Holy Crap!” The woman who’d helped homestead hundreds of acres in the wilderness beyond Caboose, who’d birthed twins—his dad and Aunt Snag—in a hand-hewn cabin with no running water, who’d faced down bears and moose as if they were the size of squirrels and rabbits, couldn’t stand a semi passing them on the road. She loved the wildflowers, though. At a rest stop she walked out into the middle of a field of bluebonnets—undid her braid and fluffed her white hair, which floated like a lone cloud in all that blue—and lay down and sang her old, big, persistent heart out. “Come on, Kache!” she called, “Sing with me, like in the old days.”

Instead, he kept his arms crossed, shook his head. “Do you know that crazy lady?” he asked Snag.

Gram was of sound mind and body at the time, just being herself, the Lettie he had always adored. Every few minutes, Aunt Snag and Kache saw her arm pop out of the sapphire drift, waving a bee away.

But in the past four years Gram’s health had declined and Aunt Snag didn’t want to travel without her. When he’d talked to Snag early that morning, she’d said Lettie was deteriorating fast. “And I’m not getting any younger. You better hurry and get yourself home, or the only people you’ll have left will be in an urn, waiting for you to spread us with the others on the bluff.”

He’d let too much time slip by. Twenty years. He was thirty-eight, with little to show for it except a pissed-off and, as of last night, officially ex-girlfriend, along with a sweet enough severance package for working his loyal ass off for sixteen years, and a hell of a savings account—none of which would impress Aunt Snag or Grandma Lettie in the slightest, or do them any good.

A stop in Seattle, another three-and-a-half hours and countless thickly frosted mountain ranges later, the plane landed in Anchorage, which Snag and Lettie grumpily called North Los Angeles. But of course it was their destination for frequent shopping trips and they didn’t hesitate to get their Costco membership when it first opened there. The in-flight magazine said that just over 600,000 lived in the state, and two-fifths of that population resided in Anchorage. So even though it was Alaska’s biggest city, it had over three million to go before catching up with LA.

He caught the puddle jumper to Caboose. During the short flight he spotted a total of eight moose down through the bare birch and cottonwood trees on the Kenai Peninsula, along with gray-green spruce forests, snow-splotched brown meadows, and turquoise lakes. Soon the plane banked where the Cook Inlet met Kachemak Bay, the bay whose name he bore. Across it the Kenai mountain range, home to nesting glaciers, rose mightily and stretched beyond sight.

From the other side of the Inlet, Mt Illiamna, Mt Redoubt and Mt Augustine loomed solid and strong and steady. But looks deceive; Redoubt or Augustine frequently let off steam and took turns blowing their tops every decade or so, spreading thick volcanic ash as far as Anchorage and beyond, turning the sky dark with soot. His mom used to say Alaska didn’t forgive mistakes. As a boy, Kache wondered if those volcanic eruptions were symptoms of its pent-up rage.

There was the Caboose Spit, lined with fishing boats, a finger of land jutting out into the bay where the old railroad tracks ended, the rusty red caboose still there.

“See that?” his mom had shouted over the Cessna’s engine that first day they’d all flown together, his dad finally realizing his dream of owning a bush plane. “The long finger with the red fingernail pointing to the mountains? I bet the earth is so proud of those mountains. Wants to make sure we don’t miss seeing them.” She tucked one of Kache’s curls under his cap, her smile so big. “As if we could! Aren’t they amazing?”

It had always been a breath-stopping view, the kind that made him inhale and forget to exhale, especially when the clouds took off, as they just had, and left the sea every shade of sparkling blue and green against the purest white of the mountains. He had to admit he’d never seen anything anywhere—even now during the spring breakup, Alaska’s ugliest time of year—that came close to this height or depth of wild beauty.

But now the view did more than take his breath away. Maybe his mom had been wrong. Maybe that strip of land was the world’s middle finger, telling him to fuck off, saying, Who you calling flat? Today that red spot of caboose looked more like a smear of blood on the tip of a knife than a fingernail. Either way, the view stabbed its way into his chest, as if it were trying to finish him off before he even landed.

THREE (#uec953bec-07ae-5dad-9e8f-52d0caf8a62b)

Snag hadn’t stopped maneuvering through her small house since Kache’s call. Kache. Finally agreeing to come home. In the wee hours of that morning she’d mistaken the ringing phone for the alarm and kept hitting the snooze button until she sat up in a panic, thinking, It’s about Mom. But no, it was Kache, calling back from Austin. Ever since they’d hung up she’d been bathing every surface with buckets of Zoom cleaner, suctioning up the cat hair and the spilled-over cat food with the vacuum, stuffing the fridge with a ready-to-bake casserole, moose pot roast, and rhubarb crunch, and wrapping the bed in clean sheets.

Snag thought she, herself, resembled a well-made bed. Polishing every last streak off the mirror, she saw her chenille robe creased under her breasts as if it were a bedspread tucked around two down pillows. They rose and fell with her deep breaths. She moved fast despite her size, wiping the counter now, putting away a pepper grinder, a bottle of salad dressing with Paul Newman’s mug on it. She closed the refrigerator door.

There was the memory of Kache, sitting on the kitchen stool, dark curly head bent over his guitar, then opening that same door and standing in front of the assortment of cold food like the refrigerator was some god requiring homage. How many times had she swatted him, told him to close the damn door? “A million? A billion?”

Since the day she had to put her mom into the home, Snag had been talking to herself. Before that, sometimes all Lettie had added to the conversation was, “Is that right, Eleanor,” but it was something.

No one but her mom still called her Eleanor. Around age nine she came home from fishing the river alone for the first time, holding up a decent-sized salmon. “Look, Daddy. I caught a fish all by myself.”

Her daddy laughed and pulled the hook out of the side of the poor fish. “Eleanor,” he said, “what you did was snagged yourself a fish.” Glenn, jealous that he was the same age and had yet to catch or even snag anything, started calling her Snag. The name took hold and never let go. Most of the town’s newcomers thought the name came from the fact that she had a gift for selling. It was true. Whether someone needed Mary Kay or Jafra cosmetics, Amway detergent, or a new house, Snag was the person to call.

Real estate had been particularly good to her. She preferred to live in her simple house, but she waxed poetic about the benefits of a sunk-in tub or a granite countertop. Lately she’d stepped back from showing houses. She’d made enough, and she wanted to give the newbies a shot. The one element in life that had come easily to Snag was money and she didn’t need to be piggy about it. She still sold products for the pyramid businesses, but more as a service to the citizens of Caboose than out of her own need. The only thing she couldn’t sell anyone on was the idea of getting the town mascot, the old Caboose parked at the end of the spit, moving again. But she didn’t have time to dwell on that now.

She climbed into the car and took a deep breath. Kache. “He’s going to want to kill me, and I can’t blame him one bit.” She wiped her eyes with the sleeve of her rain jacket, surprised to see a black smear across it. She wore the mascara for the first time in years in honor of Kache’s homecoming. It was the brand she’d demonstrated at kitchen tables, rubbing it on a page of paper, then dropping water on it, holding the paper up so the drop ran down clear as gin. Now she smoothed her fingers under her eyes: more black. She licked her fingers, ran them over and over her face, took the balled-up tissue from under her sleeve and wiped more. She adjusted the rearview mirror to check herself. “Aw, crap,” she said. It looked like someone had struck oil on her face. With all her finesse for cleaning, Snag sometimes felt that her biggest contribution to mankind was making a mess of things.

FOUR (#uec953bec-07ae-5dad-9e8f-52d0caf8a62b)

At the small Caboose airport, Kache recognized Snag before she turned around to face him. You couldn’t miss her height, a half inch shy of six feet. Long-limbed like he was, hair cropped short, with much more salt than pepper now. She was his father’s twin and they bore a strong resemblance—the deep dimples, the large gray eyes—maybe that’s why Kache had always thought of her as a handsome woman. Her back expanded, her shoulders hung limp in her hooded jacket. She fidgeted with her sleeves, touched her face. Many times that sad spring before he’d left, Kache had seen her cry with her back to him, as if she might protect him from all the grief.

He sighed, kept standing there, observing her broad back. How was it that you could leave a place for twenty years, stay away for twenty years, and walk right smack into the very center of what you left behind, like it was some bull’s-eye for which you were trained to aim?

“Aunt Snag?” He touched her arm and she jumped.

“Kache! Of course it’s you.” As tall as she was, she still had to stand on her tiptoes to swing her chubby arms around him. “Oh hon, look at you. Your momma and daddy would be so proud.”

He held her soft face, wrinkled a bit more, though not as much as he’d expected, but a little … dirty? Streaked with something. With Snag it was more likely mud than makeup. He smiled. Their eyes stayed on each other for a long minute. There was a lot to say but all he got out was, “Let’s go see Gram.”

Snag blew her nose, blew some more. “She’s not herself. And I tried and tried, but I couldn’t keep up. It’s a decent place, though. It is. We can stop on the way home.” She pulled his head down, ruffled his hair, like he was eight years old instead of thirty-eight. “You look so handsome. Kache Winkel, you’re home. Is that your only bag?”

He nodded. He’d packed the few warm clothes he still owned, along with the old holey green T-shirt he would never throw out, the one that said, No, I don’t play basketball. Denny had it printed up for him because at six foot six inches, Kache had gotten tired of being asked. And he’d packed the only item of his mom’s he’d taken, her favorite silk scarf, which had smelled of her perfume for years after she died. Snag asked him where his guitar was but he shrugged, as he had whenever she’d asked him in Austin. She raised her eyebrows, opened her mouth, but let the question go, just as she had before.

Even in the middle of winter Austin didn’t get this cold. In the car he rubbed his hands together and felt the pull and release of resistance and surrender; the place lured him back in, then yanked him hard with long lines of memories: Denny buying him beer at that very liquor store, which still sported the same flashing orange sign; his mom rushing him into that very emergency room when he was nine and had split his knee open. That same hardware and tackle shop his dad got lost in for hours while Kache waited in the truck, writing lyrics on the backs of old envelopes his mom kept in the glove compartment for blotting her lipstick. Kache wrote around the red blooms of her lip prints.

Some things had changed, sure, and yet not enough to keep away a hollow, emanating ache.

But it was breakup. Here, early spring was the depressing time of year, when the snow and ice gave way—cracking, breaking, oozing—as if the earth bawled, spewing mud everywhere, running into the darkest lumpy blue of the Cook Inlet and Kachemak Bay.

“Thought we might get to see Janie. Couldn’t get away from work?” Snag said, glancing at Kache. He shook his head. “You’re awfully quiet. For you.” She smiled and fiddled with the radio while she drove, then turned it off. It was true that Kache’s dad had dubbed him Chatty Kachey, but that was a long, long time ago. “Ah, a break from the rain.”

“We don’t get enough in Austin. I’d like a good watering.”

“In a few weeks you’ll be soaked through to the bone, I’m betting. Fingers crossed we’ll have a decent summer. Since you don’t … you know, have to get back to work … You’re staying a while, aren’t you, hon?”

“I’m thinking a few weeks.” That was the goal, anyway, if he could stick it out. It would get easier in a day or two. He wanted to hang out with Snag and Lettie. Face the things he needed to face, get out to the homestead. Snag had said a nice family was renting it. He’d try to fix whatever out there needed fixing, do whatever needed to be done for Lettie and Snag, hold it together, be strong enough to look it all in the face so he could get on with his life. Janie was right. It was way past time.

Snag pulled the car into the parking lot of the low brick and concrete building. “She’s a lot weaker, Kache. She asks about you still, though. It depends. Some days she’s clearer than most of us, and some days she’s cloudy, and some days she’s plain snowed in.”

He got out and held open the glass door—flowery pink and green wallpaper and paintings of otters, puffins, and bears on the walls of the lobby.

He nodded approval. “Not bad, considering.”

“Believe me, it’s much better than the third world prison camp they call a nursing home down in Spruce.” She smiled wide. “Hello there, Gilly.”

“So this is Kache.” A woman probably a little younger than Snag reached out and shook his hand. “Not a mere figment of Snag and Lettie’s imagination, after all.” She wore a nametag printed in oversized letters pinned on a cheery smock, had blue eyes with nicely placed crow’s feet, the kind that told you she’d spent a lot of time laughing. “If I’d known last month you were coming up, I might have been able to talk my daughter into staying. I told her we have a boatload of single men up here, but she only lasted a couple of weeks. She said, ‘Mom, I’m going back to Colorado where at least the men shave.’ That and the fact that folks regularly get their eyebrows and noses pierced by hooks while combat fishing on the Kenai, fairly crushed her fantasy version of Alaska.”

Snag touched Kache’s face. “Five o’clock shadow.”

Kache said, “Can’t help that. But it’ll be gone by morning.”

“See, Gilly? Your daughter missed out.”

Kache rubbed his chin. “It won’t be long before I start forgetting how to shave, I suppose.”

Even though the place was not-bad-considering, as he followed Snag down the hall it still smelled faintly of urine, medicine and decay, all mixed with boiled root vegetables.

The TV shouted an old black-and-white film he didn’t recognize, wheelchairs facing it like church pews. Grandma Lettie sat off to the side with her head in a book. Literally. The book lay open on her lap, her head drooped to almost touching it. She wore her hair in the same braid she always had, but it was as thin and wispy as a goose feather. In the photos of her as a young woman it had been a thick, dark rope coiling down to her waist.

Kache knelt in front of her. A thin line of drool hung from the center of her top lip down to the page. He wiped it with his sleeve while Snag handed him one of her crumpled tissues. “Gram?”

She looked up, peering, and then her mouth opened in a smile.

“Kachemak Winkel!” The smile slipped down. “Where have you been?

“I’ve been in Texas, Gram.”

She shook her head. “Where’ve you been?”

“Working, Gram.” His answers sounded feeble.

“No.” She started to whimper and turned to Snag, whispering loudly. “Does he know about the crash?”

Snag nodded. “Yes, Mom, he was here. Remember?”

“But he didn’t die.”

“That’s right.”

She whispered again, enunciating slowly, her eyes wide, “He was supposed to go on that plane.”

Kache swallowed hard. Snag held his elbow, moved a lock of white hair from Gram’s vein-mapped forehead. “Mom, Kache has been away. Just away. From here.”

Gram raised her eyebrows, nodding, and rubbed Kache’s long hand between her two boney speckled ones. “Of course you have, dear. Oh, but …” She looked over her shoulder, then back at him. Her voice raised higher, almost a child’s. “It was like all four of you were dead. Now. At least we have you back.” She picked up his hand in hers, moving it up and down to the beat of each word: “And. That. Is a. Very. Good. Thing.”

“Thanks, Gram.” How had he stayed away so long? How had he come back? He was tempted to grab himself a wheelchair and steal the remote from the guy in the Hawaiian shirt and cardigan, flip the channel to the DIY network, and let a few more decades go flickering past.

Instead, he drove with Snag over to her place. He braced himself for the onslaught of mementos but, surprisingly, Snag didn’t have one piece of furniture or even a knick-knack or painting of his mother’s. Sentimental Aunt Snag, who loved her brother and adored her sister-in-law. Where was all their stuff? It didn’t make sense to sell or give away every single thing. And when Kache asked about heading out to the homestead she changed the subject. She wouldn’t have sold it, would she? He knew she’d sold his dad’s fishing boat right away to Don Haley, but all four hundred acres, without saying a word to Kache? It was true that Kache had given her power of attorney, back when he was eighteen and didn’t want to deal. But she wouldn’t have sold it without telling him. No way.

Later that afternoon he went to the Safeway for her and bumped into an old friend of his father’s, Duncan Clemsky. Duncan clapped him on the back, kept shaking his hand while he talked. “Look at you, Mr. City Slicker. I still think of you when I have to drive by the road to your daddy’s land. Only time I get out that far is when I make a delivery to the Russian village.”

“The Old Believers are accepting deliveries these days? Progressive of them.”

“Some of them at Ural even have satellite dishes. Going soft. Won’t be long until they’re wearing pretty, useless boots like those.” He nodded toward Kache’s feet. “Change eventually gets ahold of everyone I suppose.”

“Suppose so,” Kache said, his face heating up. Nothing like a lifelong Alaskan to put you in your place. He wanted to ask Duncan if Snag had sold the land, but he wasn’t about to let on he didn’t know—if it was even true. No need to get a rumor heading through town that would end up like one of the salmon on the conveyor belt down at the cannery, the head and tail of the story cut off and the middle butchered up until it became something unrecognizable.

“You’re gonna need to get some real boots before folks start mistaking you for a tourist from California. Thought you were at least in Texas, my man.” He shook his head and winked. “You tell your aunt and grandma I said hello, will you?”

Kache nodded. “Will do, Duncan. Same goes for Nancy and the kids.”

That opened up another ten minutes of conversation, with Duncan Clemsky filling Kache in on every one of his five kids and sixteen grandchildren, and seven seconds of Kache filling Duncan in on the little that Kache had been up to for the last twenty years. “Yeah, you know … working a lot.”

On the way back to Snag’s, Kache decided that if she didn’t bring up the homestead that evening, he would just come out and ask her if she’d sold it. Part of him hoped she had, the other part hoped to God she hadn’t.

FIVE (#ulink_81f7530b-858d-5405-9a8e-0b91f319adf3)

Snag filled the sink with the hottest water she could stand while Kache cleared the dinner dishes. She’d decided on Shaklee dishwashing liquid, since she’d used Amway for lunch and breakfast, and now she was trying to decide how on earth to tell Kache about the homestead.

Staring at her reflection in the kitchen window, she saw a chickenshit, and a jealous sister, and there was no hiding it. Looking at it, organizing the story in her mind, lining it up behind her lips: This is how I let it happen. It started this way, with my good intentions but my weaknesses too, and then a day became a week became a year became a decade became another. I hadn’t meant for it to happen like this, I hadn’t meant to.

She squeezed more of the detergent; let the hot water cascade over her puffy hands. She laid her hands flat along the sink’s chipped enamel bottom, where she couldn’t see them beneath the suds. If only she were small enough to climb into the sink and hide her whole self, just lie quietly with the forks and knives and spoons until this moment passed and she no longer had to see herself for what she really was. Sometimes drowning didn’t seem so horrible when she thought of it in those terms. Better than dying the way Glenn and Bets and Denny had. She shivered even though her hands and arms were immersed in the liquid heat.

It would have brought them honor in some small way, if she’d done the simple thing everyone expected of her. Simply take care of the house and Kache. But she’d failed at both.

“Aunt Snag?” Next to her, he held the old Dutch oven with the moose pot roast drippings stuck on the bottom. There were never any leftovers with Kache, even now that he was a grown man. “Are you okay? Want me to finish up, you catch the end of the news?”

“No … Well … Okay.” She dried her hands on the towel and started to walk out, but turned back. “I’ve got to tell you something, hon, and it’s not going to be pretty. You’re going to be real upset with me, and I won’t blame you one bit.”

“You sold the homestead.” It was a statement, not a question.

“What?” she said, though she’d heard him perfectly.

“You sold it. You sold the homestead.”

“No, hon. I didn’t. I didn’t sell it.”

He smiled, sort of, a sad, tight turning up of his mouth, while his shoulders relaxed. “I guess I’ll need to go out. Check up on things. I’ve been meaning to ask. But it’s hard, thinking about driving up, seeing it for the first time, you know? Do you go out there a lot?” Still such youthfulness to his face. He didn’t seem like a grown man who’d seen a lot of life. Snag couldn’t tell what it was, exactly. Trust? Vulnerability?

She said, “Not a lot, no.”

“Just enough to take care of things.” His voice didn’t rise in a question.

“No, not that much even.’ She breathed in deep, searched in her pockets and up her sleeve for a tissue. “I haven’t been out there at all.”

“This spring?”

“No. I mean not once. Not at all.”

“All year?”

“No, Kache. Not all year. Not ever. Not once. I never went out like I told you I did. I planned to a million times, but I never closed it up, never got all your stuff, never put things in storage. I never …”

He stood with his mouth agape for what seemed to Snag like a good five minutes. “Wait a second. You said you’d been renting it out. No one has been out there since I left? Not even the Fosters? Or the Clemskys? Jack? Any of those people? They would have been glad to help. They would have insisted on it.”

Snag leaned against the counter for support, inhaled and exhaled. “Don’t you see? I insisted it was taken care of. I told them I’d hired someone … to scrape the snow off … patch the roof … run water in the pipes.”

“I don’t understand. Why?”

“Embarrassed by then. I hadn’t even been out since you left, to water the houseplants, or—I’d never planned to be so negligent—clean out the pantry.” She fell silent. The water dripped on and on into the sink. “I left it all. I tried, I drove part way dozens of times but then I’d chicken out and turn the car around.”

Kache didn’t scream and holler at her like she’d expected. He hugged her, a big old bear of a hug. In his arms, the sense that she might not be worn down to a nub by shame after all. But grace dragged another weight of its own. He said her name, tenderly, and sighed. “You know it’s the anniversary today, almost to the hour?” She nodded because she did know without thinking about it, the way a person knows they’re breathing. He told her it was okay, that he did understand, more than he wanted to admit, that he’d fought the same problem in trying to come back.

She was glad she didn’t use the line she’d been holding onto in case she needed it, the fact that at first, way back when, she’d waited for him to return so they might go together. And that’s what she’d pictured happening now, the two of them braving the drive out together. But forgiving or not, he’d already let go of her, grabbed the car keys, called out, “I’ll be back in a while. Don’t wait up,” and was tearing out of the driveway when she whispered, “Wait.” But she knew. Even though he’d reacted with kindness, she could see the shock pumping through him and that he needed to put some distance between them. It scared her to have him go off upset. The tires screeched like they did when Kache was still a teenager, as if they’d woken up the morning after the crash and no time had passed at all.

SIX (#ulink_adc0aa33-210c-55aa-bcff-062a2422463b)

Kache couldn’t get to the house fast enough now. Now that too much time had passed and the place would most likely have rotted to ruins. The cabin Grandma Lettie and Grandpa A.R. built with their own hands in the early Forties, added onto in the Fifties. The place that his mom and dad added onto again, then transformed into a real house in the Seventies. The house Kache grew up in and loved and the only place he ever called home. Reduced to a pile of moldy logs.

He guessed that when he got out to the homestead it would be dark. The days were already starting to get longer and in less than a month would go on until midnight, though that didn’t help him now. He had no idea if the moon would show up full or a sliver, waxing or waning. Yes, he knew the DIY network lineup by heart but he’d lost track of the night sky long ago. He reached under the seat for the flashlight he figured Snag would have stowed there and set it next to him. Plenty of gas—he’d filled it that afternoon, so he’d make it out and back with some to spare.

Keeping an eye out for moose, he drove the first part of the road, the paved part, fast. Here the houses stood close enough to see each other, all facing south to take advantage of the view—the jagged horizon of mountains marooned across six miles of Kachemak Bay.

Kachemak. A difficult name to have in this town, the kids teasing him in his first years at school, when the teacher let his full name slip out during roll call instead of the shortened version he’d insisted on—pronounced simply catch—the kids adding Bay onto the end of it. Then in high school, the girls blushing and calling him What a Kache, asking him if he would write a song for them. Or the boys throwing balls of any type his way and saying Here, Kache, followed by You can’t! Kache!, which was absolutely correct.

At first his mom told him they named him for the bay because it was the most beautiful bay she’d ever seen and he was the most beautiful baby she’d ever laid eyes on. Whenever Denny protested, she’d laugh and say, “Den, I won’t lie to you. You had the sweetest little squished-up turnip face. Fortunately, you grew into your dashingly handsome self.”

Later, when Kache was sixteen and his father decided he was old enough to be let in on a secret, he told Kache that was all true, but there was more. Kache was conceived, his father said, grinning, in the fishing boat on the bay. The sun had been warm and the fishing slow—both rarities for Alaska. “Proved to be a fruitful combination, heh?” He slapped Kache on the back so hard it about knocked him over. “Denny, of course, was conceived on a camping trip to Denali.” Kache had told his dad that he didn’t need quite that much information, thank you very much.

He hit a pothole and mud splattered on the hood and windshield. Kache knew the house was probably too far out of the way and too well hidden for anyone to stumble upon. Old Believers wouldn’t want anything to do with a house outside their village, and the deepest cut of canyon on the whole peninsula added an uncrossable deterrent. Nobody with a brain would descend that canyon. The one other access besides their five-mile private road was by the beach, and only during the lowest tides. Most likely, the house stood its ground against the snow and rain and wind until the chinking filled like sponges, the roof turned to cheesecloth, the furniture rotted with moss, all his mother’s books … All those books. His mom’s paintings and her quilts and the photographs. The photographs he had never wanted, now he wanted them, even the blurry black-and-white ones he’d taken when he was five, when he’d snapped a whole roll of film with Denny’s new camera, and Denny had threatened to strangle him.

Damn it, Aunt Snag.

Where you been? Where you been?

Damn it yourself, Winkel. He hit the steering wheel, pulled on the lights, leaned forward as if that would make him get there faster.

The road turned to dirt—mud this time of year. A plastic bottle of Advil lodged between the seats rattled on and on. This was the part of the road he knew best, the part his old blue Schwinn had known so well that at one time the bike might have found its way back home without anyone riding it.

No turning around now; the pull grew stronger, magnetic.

He wasn’t the first one to leave and get pulled back. In the mid-Sixties, even his dad couldn’t wait to get away, had gone off to Vietnam in a huff of rebellion mixed with a desperation to see someone other than the all-too-familiar faces in Caboose, Alaska. But he returned with a deep disdain for the World Out There. In a few short, horrific years, he said, he’d learned a lifetime of lessons about human nature and wasn’t interested in learning more.

“I’ll take plain old nature with a minimum of the human element, thank you,” he was fond of saying.

But then he’d met Bets, and she restored his faith in humankind, or at least in womankind, and instead of the life he’d planned as a hermit bachelor, he became a family man. Still, he answered to no one (except, it was a known fact, Bets) and lived off the sea and the land for the most part, earning a decent living as a fisherman. They’d been able to transform the cabin into a real house, with huge windows facing the bay and Kenai Mountains. Bets had eased him into one compromise after the other over the years, first with a generator, and then, once Caboose Electric Association extended their service, real electricity, although they never did have central heating. She’d confided to Kache that it was next on her list, right before the Cessna crashed.

It made sense for homesteaders, like all farmers, to have large families to help with the work. But Lettie and A.R., and later Bets and Glenn, had only had two children. Fortunately, Denny, like his father Glenn before him, was able to do the work of three or four strapping boys. Kache, however, had been a disappointment, and his father had a hard time hiding just how much Kache let him down on a daily basis.

A bull moose plunged through the spruce trees, and Kache slowed to a stop and let it cross in front of him. Its long legs navigated the mud with each step before it disappeared into the alder bushes. Kache drove on and turned down their private road to the homestead. But he quickly pulled over. “Road” was an optimistic term. A churned up pathway of sludge obstructed by downed spruce and birch trunks and overgrown alders was more like it. He grabbed the flashlight, which was also optimistic, the light dim, the battery exhausted. Aunt Snag knew to keep the battery fresh, but Kache should have checked it before he left. He didn’t want to walk in the dark through moose and bear country at the onset of spring when the animals experienced the boldest of hunger pangs.

His cellphone was useless; no service. He should turn back. Get in the car and head into town and return tomorrow. But his dad, his mom, Denny—they seemed so close: a slap on his back, an arm around his shoulders, as certain as the cold on his feet, and he shivered from both. He smelled the fire from their woodstove, as if they kept it burning all these years. All around him they said his name in all its variations and tones, so achingly clear: “Kache, honey?” “Oh, Kaa-achemak, there’s my Widdle Brodder …” “Did you hear me, Son? Pay attention.” He heard their snow machines, though there wasn’t any snow, though there wasn’t any them. He didn’t believe in heaven, exactly, but this place was thick with recollections and maybe something more. If their spirits watched him, somehow, from somewhere, didn’t he want to prove he had become capable of more than any of them thought possible? But had he? No. A city boy number-cruncher-turned-couch-potato who wore pretty boots and forgot a decent flashlight would hardly invoke awe. Still. If they were waiting, they’d been waiting twenty years and he didn’t want to make them wait another day.

He made his way through the mud, tripping, sinking, until the full moon rose from behind the mountains. Like a helpful neighbor in the nick of time, it shined its generous gold light through the cobalt sky. A wolf howled, holding a single lonely note in the distance. The scent of spruce and mud and sea kept dredging up the imagined hint of smoke. All those scents had always come together here. Even in the summers, a fire burned in the woodstove.

Now Kache spotted the downed trees clearly without the flashlight, and he walked as quickly as his mud-soaked city boy boots would allow—until the last bend, where he stopped and readied himself for what lay ahead.

It was then, as he stood on the road that was no longer a road, breathing deep, heart hammering, that the realization jarred him. The familiar scent. The spruce, the soaked loamy earth, the sea; yes, yes, yes. But wood smoke? It was too strong, too distinct now, not merely his imagination. It was definitely the smell of wood burning, and coal too.

He edged around the last corner, saw the house through the boughs of spruce and naked birch and cottonwoods. It stood, not a dejected pile of logs, but tall and proud, glowing with warm light.

What?

Who?

Smoke rose straight up from the chimney, as if the house raised its hand. As if the house knew the answer.

SEVEN (#ulink_bb61b293-4385-585a-9a16-c140752f5ede)

Kache stood, staring, the cold mud oozing into his boots and now through his socks. The house stared back as it always had in his mind, glowing with light and life in the middle of the cleared ten acres.

Who in the hell?

Sweating, watching, allowing for the strangest glimmer of hope. Maybe he really had been dreaming, really had been sleeping, and now that he’d finally awoken, life might resume as it had before? Maybe all and everyone had not been lost? Maybe only he had been lost.

In these last two minutes he felt more alive than he had in two decades. Maybe he’d been under some sort of spell, broken at last on this anniversary. His mom would love the mysticism and synchronicity of that.

He shook his head, boxed his own ears. What he needed was common sense. His dad would have reamed him for not grabbing Aunt Snag’s .22 that hung on the enclosed back porch. As much as Kache hated guns, never got himself to actually shoot one, he knew it was crazy to approach the house without carrying one, especially given the lights and smoke. His dad used to say it didn’t matter if you were far to the left of liberal, if you walked by yourself in the boondocks of Alaska, you should carry a gun.

His feet started moving forward anyway. Forward to his old house, his old room. Who in the hell?

Inside, a dog barked. A shadow passed by one of the windows. The shade went down, snapped up again, quick as a wink, then shut. The other shade went down. The soft light behind them off now, replaced with the dark he’d expected to find in the first place.

He pressed his back against the old storage barn, took deep breaths and tried to line up his thoughts, which kept ricocheting off each other. He should go back, return in daylight with the gun. Call Clemsky, Jack O’Connell, a few of the others. He licked his palm and made a small circle on the mud-covered window beside him. He peered in. It was dark, and he barely made out the outline of his dad’s Ford pickup. Aunt Snag had even left that, probably driven it home that day from where his dad had parked it by the runway. She should have used it. That would have meant something.

The dog was going nuts now, continuously barking. Kache pushed on the storage barn side door; it wasn’t locked, opened easily. Along the wall he felt for the shovel, the hoe, the rake. He decided on the sharp, stiff-bladed rake. Better than nothing.

Hovering behind a warped barrel, then a salmonberry bush, he tried the back door of the house, knowing it would be locked. He crept along to the first kitchen window, remembering. That window never did lock. He slid it open, pulled himself up on one knee, lowered the rake in first, then jumped down inside with a thud.

The barking stopped, became a whine and growl. He pictured a hand muzzled around the dog’s nose. Kache tried to make himself smaller by crouching, then slipping along the wall. The thought came to him: I am not the intruder here. This is my house. He’d forgotten, taken on the attitude of a thief instead of a protector, and now he stood straight with his rake, as if that would shift the perspective of whoever was upstairs, as if the moment was a black-ink silhouette that changed depending on how you looked at it.

The whining, the growling. Kache could smell his own nerves, so of course the dog could. He ran his hand along the blue-tiled kitchen counter, up to the light switch, flicked on the lights. Nothing had changed. As always the woodstove warmed the large living room, which had once held four rooms before his mom and dad remodeled. The same furniture stood in its assigned places. His mother’s paintings still hung heavily on the thick, chinked walls. Photos of the four of them, baby pictures, wedding pictures, Christmas pictures all lined the top of the piano. He ran his finger along the top; free of dust. Games and books crammed the shelves. Kache fingered the masking tape his mother had sealed along the broken seam of the Scrabble box. He fought urges to throw the rake, to vomit, to leave.

Upstairs, another growl. Kache choked out, “Hello?” He listened. Nothing. “Hello?”

Then, rage. He pounded up the stairs. “Answer me! Answer me!” He flung open doors and flipped on lights to bedrooms that stood like shrines to the dead. All as they’d left it. In his room, a yellowed poster of Double Trouble was still stapled to the wall, Stevie Ray Vaughan still alive and well. As if neither his plane nor Kache’s family’s plane had ever gone down. As if Kache still slept in the bottom bunk and dreamed of playing the guitar on stage.

Under the bed, the dog let out barks like automatic ammunition, scrambling his claws on the wood floor. Kache held out the rake. “Who’s there!” An arm shot out, fist clenched around the handle of Denny’s hunting knife. But even more startling than the knife: the arm, clad in the sleeve of his mother’s suede paisley shirt. The shirt Kache and Denny bought in Anchorage for her birthday, and that she referred to as the most stylish, most perfect-fitting shirt on the planet that had somehow forged its way to the backwoods of Alaska. “Mom?” Kache whispered under the barking dog. “Mom?” he said louder, his eyes filling.

The dog poked his nose out, then was yanked back by the collar. A husky mix. Kache bent down, trying to see through the thick darkness. “Mom? That’s not you?”

The knife retreated and the hand reappeared, unfolded. Not his mother’s hand. It spread, splayed and pressed its fingers on the floor, until a blonde head emerged, and then a face looked up. Not his mother’s face. That was all he saw. It was not his mother’s face, and a new grief slammed him to his knees.

Mom.

Minutes went by before he realized the dog was still barking and this other face that was not his mother’s looked up at him for some kind of mercy, and though he hated the face for not belonging to his dead mother, he saw then, that it was a woman’s face, that it was round, that blue eyes begged him, that lips moved, saying words.

“Kachemak? It is you? You are not dead?”

EIGHT (#ulink_1d27a0ab-1b61-5f22-9b38-5e1dad7db067)

There had only been one visitor, years before.

Kachemak had caught her so completely unprepared that her heartbeat seemed to be running away, down to the beach, while the rest of her waited.

He looked older, his face more angled than in the photographs. But he still had the same curly hair, though shorter now, and the same heavy brows. His height—taller than the rest of the family in every photo—also gave him away. He asked her to call the dog off, and so she did, and pulled herself out from under the bed though her arms wobbled like a moon jellyfish. She shoved her trembling hands in her pockets and tried to appear brave and confident.

And yet she felt grateful it was him. She knew that Kache, as the family called him, was a gentle soul. But she also knew it was possible for a man to appear kind and yet be brutal. She fluctuated between this wariness and wanting to reach out and hold him as a mother would a child—even though he was older by ten years.

All this time she’d pictured him a boy like Niko, not a man like Vladimir. And all this time she’d thought him dead. She’d figured it out on her own, but then Lettie had confirmed. “You may as well be here. They’re all gone,” she’d said and snapped her fingers. “And Lord knows they’re never coming back.”

When Nadia asked, “Was it the hunting trip?” because she’d seen a reference to it on the calendar and elsewhere, Lettie nodded and held a finger to her lips while a single tear ran down her worn cheek and Nadia never asked her about it again. They’d had an unspoken mutual agreement not to pry, to leave certain subjects alone.

But now Kache stood before her, older, a grown man who had called her “Mom.” Was Elizabeth alive too?

“Who are you?” he asked. She shook her head. She should have not spoken earlier, should have pretended she did not understand English. But already she’d given herself away. “Look—do you know me?” he said. “You called me by name. You thought I was dead? Do I know you?”

She shook her head again, walked back and forth across the small room, touching chair, lamp, bed as she went. Moving like this, she could turn her head and glimpse him sideways without feeling so exposed face to face. The years had marked him, but he still had a youthful expression, those big dark eyes. Though Lettie had stayed clear of certain topics, Nadia knew so much about the boy: a gifted musician, an awkward teenager who felt out of place on the homestead, who fought bitterly with his father and had been a constant disappointment to him, but whose mother understood him and felt sure he would find his way. Nadia knew when he lost his first tooth (six-and-a-half years old), when he said his first word—moo-moo for moose—(ten months old). How he cried when his mother read him Charlotte’s Web.

“Can you stop pacing?”

She stopped. They stood in the lamplight, he staring at her, she staring down at her slippers. His mother’s slippers. He didn’t know anything—not one thing—about her, not even her name. All these years and years and years nameless, unknown. Only Lettie knew her, and Lettie must be dead. Nadia was afraid to ask.

“What’s your name?” Kache said. “Let’s start with that.”

Leo let out a long sigh and rested his head on his paws, sensing no more danger. How could a dog get used to having another human around so quickly?

Squaring her shoulders, taking a deep breath, she said her name. “Nadia.” She wanted to shake him and call out, I AM NADIA! but she kept quiet, still, erect.

He held out a large hand. “I’m Kache.”

She kept her hands in her pockets and her eyes to the ground, even though part of her still wanted to hug him, to comfort him. She practiced the words in her head, moved her lips, then put her voice to it without looking up: “Your mother is alive?”

“No. She died a long time ago.”

At once the new hope vanished. “Then why do you ask this, if I was your mother?”

“My brother and I gave her that shirt.” She felt her face flush. “I lost my head for a minute. You scared the hell out of me. And I still have no idea who you are.” She looked up to see him cross his arms and take an authoritative stance, then she turned her eyes back to the floor.

It was her turn now to speak. This, a conversation. She was conversing with the boy she thought had died, whose bed she slept in, whose jeans she wore, always belted and rolled up at the cuffs. She had talked to herself, to Leo, to the chickens and the goats and the gulls and the sandhill cranes, to the feral cats, to any alive being, driven by the fear that she might forget how to talk. She hadn’t spoken to another human except for Lettie, four years ago. But here she was, speaking with someone, in English, no less, which is what felt natural to her now after reading nothing but English all this time.

“Nadia.” He nodded as he said it, as if he liked the name.

Her name. It twisted through her, and she hung her head as tears leaked down her cheeks. Soon a sob escaped, and then another. She did not cry often. What was the point? But here she was, crying for every day she hadn’t.

“What’s wrong? I won’t hurt you, don’t cry …” but she could not stop. She had been so alone, so utterly alone for too many years, more than were possible and now, all changed. Here was someone she knew, someone who now knew her name, knew she was alive, someone who might help her or might turn on her. He touched her arm and she jumped. He stepped back and said again, “It’s okay, I won’t hurt you.”

Through the stuttering gasps, more words erupted, but they came in Russian, too loud, almost screams:

I am Nadia! I am Nadia! I died when I was 18.

NINE (#ulink_572d48a4-a88e-5103-8f6a-aa8ae6f91c12)

Snag lay in bed, waiting to hear the gravel popping under her truck’s tires, trying not to worry but worrying anyway. Maybe Kache wouldn’t come back. Maybe he’d just drive straight to the airport and take the next flight out. She hoped not. It was so good to have him home, even though he’d brought all their ghosts with him, and now those ghosts plunked down in her room, shaking their heads at her, whispering about how disappointed they were that she hadn’t once gone back to the homestead, at least for the photo albums.

She did have the one photo. Opening the drawer to her rickety nightstand, she pushed aside the Jafra peppermint foot balm. She told her customers how she kept it in that drawer. “Just rub some on every night and those calluses will feel smooth as a baby’s butt.” She never actually said she rubbed the stuff on herself. No one had ever felt the bottoms of her feet, and she reckoned no one ever would. Under the still-sealed Jafra foot balm was an old schedule of the tides, and under that lay a photograph wrapped in tissue with faded pink roses. This was what she was after. She carefully unwrapped it and switched on the lamp, though she almost saw the image well enough in the moonlight.

Bets at the river: tall and slender, wearing those slim, cropped pants Audrey Hepburn wore, a sleeveless white cotton blouse and white Keds. Her hair swept back from her face in a black crown of soft curls. She had red lips and pierced ears, which until then Snag had thought of as slightly scandalous but on Bets looked pretty; she wore the silver drop earrings her Mexican grandmother had given her that matched the silver bangles on her delicate wrist.

Snag remembered handing her the Avon Skin So Soft spray everyone used because mosquitoes hated it. Snag had broken some company record selling bottles of the stuff to tourists. Bets sprayed it on her arms and rubbed it in. Her skin glistened and looked oh so soft.

Bets didn’t look like anyone Snag had ever come across in Caboose, or even Anchorage. Half Swedish and half Mexican, and from Snag’s perspective, the best halves of both nations had collided in Bets Jorgenson. She’d grown tired of her job as an editor in New York City, jumped on a train, then a ferry, and come to visit her Aunt Pat and Uncle Karl, who at the time lived in Caboose. Pat and Karl had asked Snag to take their niece fishing along the river.

That day Bets, clearly mesmerized, seemed content to watch Snag, so Snag was showing off something fierce. Everyone agreed: Snag was one of the best fly fishermen on the peninsula.

Bets sighed, dropped her chin onto her fists and said, “It’s like watching the ballet. Only better.” She drew a long cigarette out of a red leather case, lit it with a matching red lighter, and said she’d never seen a girl—or a boy, for that matter—make a fly dance like that. “It seems the fish have forgotten their hunger and are rising just to join in on the dancing.” She studied Snag late into the day, kept studying her, even after Snag fastened her favorite fly back onto her vest, flipped the last Dolly Varden into the pail, then pulled the camera from her backpack and took the very picture of Bets she now held in her hand. Bets sat on a big rock, legs crossed at the ankles, pushing her dark sunglasses back on her head, biggest, clearest smile Snag had ever seen. That picture had been taken a week and two days before Glenn returned home from Fairbanks and fell elbows over asshole in love with Bets too.

TEN (#ulink_884d089b-50a8-5051-a0b6-8eb1ea9127b3)

The woman threw back her head and screamed in a foreign language, then, dragging the dog, ran into the bathroom. She locked the door. Kache pressed his ear against it and asked her to come out but she didn’t answer.

Downstairs on the hall tree hung his old green down parka with the Mt Alyeska ski badge his mother had sewn on the collar. He yanked it on over his lighter jacket.

Outside. Fresh air. Breathe. The moonlight now reflected in a wide lane across the glassy bay, like some yellow brick road beckoning him to follow it. Instead he headed through the stale snow and fresh mud of the meadow toward the trail. He walked fast, puffs of steam marking his breaths like the puffs that sometimes rose from the volcanoes down across Cook Inlet.

He could erupt any moment.

He could do his own screaming.

Who the hell do you think you are? This is MY house. MY clothes. MY mother’s shirt.

How long had she been here, eating, bathing, sleeping, breathing in his memories? And who else? How many others had made his home their own?

At the biggest bend the trail opened to the left, and there, five paces away, the plunge of the canyon. He didn’t go another step. He shivered—partly from the cold, partly from childhood fears.

In the quiet, a hawk owl called its ki ki ki and the canyon answered Kache’s ranting with questions of its own.

YOUR home?

Have you given a rat’s ass about one inch of this land or one log of that house?

Has it occurred to you? That strange woman may be the only reason YOUR home is still standing?

Kache shook his head hard enough to shake his thoughts loose. The canyon obviously didn’t speak to him like that. To prove it, he did what they’d all done a thousand times, whenever they’d arrived at that spot on the trail:

Across the dark, vast crevice he yelled, “HELLO?”

And the canyon answered as it always had, “Hello …? Hello …? Hello …?”

ELEVEN (#ulink_e5a3c0ce-d96a-5ab0-a953-9a73417d58bb)

The front door closing, his footsteps clunk clunking down the porch stairs. She peeled back the curtain to see him cross the meadow. Where was he going? She turned on the bathroom light and stared at her reflection in the medicine cabinet. Her hair was disheveled from climbing under the bed, so she pulled out the elastic band and brushed. Leo lay down at her feet.

Nadia touched her fingertips to her lips. “Hello,” she said to the mirror. Her voice shook. All of her shook. Her throat seared from the screaming. But she did not scream now. She imagined her reflection was Kachemak and she kept her eyes from looking away. It was one thing to talk to plants and animals and quite another thing to have a conversation with a human—with a man.

“I am frightened.” No. “I am fine. Fine. I go now.”

She raised her chin, put her hand to her hair.

“Thank you for letting me stay.”

Her eyes narrowed. “Stay away from me or I kill you.” She placed her fists on her hips. “Son of bitch. Damn you to hell, son of bitch.”

But Kachemak’s mother was Elizabeth. Kind, smart Elizabeth. And this was her Kache. “I apologize. Your mother is not bitch. Your mother is very good. Your grandmother is very good.” She touched her throat. “Kache? Please? You are still good person also?”

TWELVE (#ulink_93798f63-c04d-5abc-81fb-f318129d035d)

The sun pulled itself up over the mountains to the east, casting salmon-tinged light on the range and all across the bay, even reaching through the large living-room windows. Kache sat sipping dandelion root tea with the woman Nadia, she in his mother’s red-and-white-checked chair, he on the old futon. Neither had slept. Only the fire crackling in the woodstove broke the silence between them. She burned coal and wood, which filled the tarnished and dented copper bins next to the stove. She must have collected the coal on the beach the way his family had done. It smelled like home.

The fire popped and they both jumped. “Bozhe moi!” Her hand went to her mouth, her eyes still downward. “Sorry.”

Wait—that language, her accent—Russian?

An Old Believer?

In junior high Kache wrote a Social Studies report on the Old Believer villages. The religious sect had descended from a band of immigrants who’d broken off from the Russian Orthodox church during the Great Schism of the seventeenth century, and later, during the revolution, fled Russian persecution, immigrated to China, then Brazil, then Oregon, before this particular group feared society encroaching, influencing their children. They moved to the Kenai Peninsula in the early nineteen-sixties, beyond the end of the railroad line, past Caboose, then still called Herring Town, and staked their claim to hundreds of acres beyond the Winkels’ own vast acreage.

At first everyone pitied the Old Believers. A child died in a fire and a woman was badly scarred trying to save her daughter. “They’ll never make it through another winter,” locals predicted about the small group of long-bearded men and scarf-headed women. But then a baby girl was born, and the Believers saw the tiny new life as an encouragement from God. In the spring they began to fish and cut timber. They built wood houses, painted them bright colors—blue and green and orange, and more Believers came from Oregon. They built a domed church. Eventually they too divided over religious differences and the strictest of the group ventured deeper into the woods. But both groups lived separated from the rest of the world, exempt from laws other than their own rituals, unchanged since the seventeenth century, which they believed were from God. Back in the Seventies, Kache’s dad said they ignored a lot of the fishing laws, and when the fishermen had a slow year, they often blamed the Old Believers.

“They’re lowly.” Kache recalled Freida—his mom’s bridge partner—spitting the words across the kitchen table one night. His parents adamantly objected.

But his mom had her own concerns. “I just worry that they’re so steeped in religious tradition that they have no awareness of equal rights. I’ve heard they marry those poor little girls off when they’re thirteen.”

Freida’s husband, Roy, said, “I’ll tell you where I want equal rights. Out on that water, that’s where.”

His mom said, “I wonder if those young girls even have a prayer.”

“Bets,” Roy answered, “they pray all damn day.”

No way would an Old Believer woman step outside her village except to run an errand in town. Look at Gram’s afghan, those photographs, the magazines, back from 1985 and before. Even the Ranier Beer coasters. Nothing has changed. It’s like sitting in 1985 with a woman from 1685—if she even is an Old Believer. What if there’s poison in the tea? (He set down his cup.) If the tea doesn’t kill me, her husband is going to come in and shoot me.

Kache wanted to ask her many questions but the despair rose from his spinning mind, settled in his throat, and he was afraid that if he spoke too soon he too might succumb to tears. He’d fallen smack dab into that day when he’d sat in this living room, a little high, playing his guitar, tired from having done his chores and Denny’s as a way of apologizing, waiting for the three of them to drive up and pile in the door with stories of their weekend. His dad would be gruff at first. But once he’d seen that Kache had not only finished the chores, but cleaned the awful mess from the fight, repaired his bedroom door, even gone down to the beach and emptied the fishing net, all would be forgiven.

Jesus.

The dog stayed at her feet, watching Kache. A husky and something else, maybe a malamute … it didn’t have a husky’s icy blue eyes, but big brown loyal eyes.

“What’s your dog’s name?”

A long silence before she whispered, “Leo.” Leo’s ear went up and rotated toward her.

“Are you into astrology or literature?” he asked, mostly as a joke to himself.

But she surprised him and said. “Tolstoy. Almost I name him Anton.”

His mom would be proud. “You have good taste. So …” He smiled. “I guess we’ve established the fact that we’re not going to kill each other.” He picked up the tea and sniffed. “Although I’m not sure I trust your tea.”

She lowered her chin. “I would not poison.”

He tried a smile again that still went unmet. “Fair enough. I do have some questions.”

“Yes.” She placed her hands on the knees of her jeans—his old jeans, actually. He recognized the patch his mother had sewn on the right knee. Denny and he used to tease her because sometimes she sewed patches on their patches.

“How long have you been here?”

She studied her hands as though she’d just discovered them, let a moment pass before she held them out, fingers splayed.

“Ten days?”

She shook her head.

“Ten months?”

Again, no.

“Ten years?”

A nod.

“How old are you?”

“I am twenty-eight years old.” With this, her eyes filled again and she quickly wiped her face.

“Do you know my Aunt Snag?”

She shook her head.

“You came with your folks? Where’s your family?”

“I have none.”

“Who lives with you here?”

She shook her head, kept shaking it.

“But you haven’t been here by yourself. Tell me who else has been living in my house.”

Her hands went over her ears now.

Kache took a deep breath and lowered his voice. “I’m not angry. I’m confused.” She finally looked up, but not directly at him. “I don’t know who you are and who else might come barging through the door with a gun.”

“I am alone.”

“I’m wondering if you’re an Old Believer?”

She nodded again, one slow dip of her head.

“With an entire village? Big family? Ton of kids? But you’re not wearing a long dress.”

With this she stood, and the dog rose and followed her to the stairs.

“Wait. Nadia, please. I need some answers here.”

She turned, whispered, “I cannot.” She was tall, sturdy. She’d rolled up his jeans and cinched them with a belt. Her back faced him again, her gold drape of hair, which had been tied up the night before, reached past her waist. The Old Believer women he’d seen shopping in town always covered their hair with scarves.

He let her and the dog go upstairs. The door to his old room clicked shut.

No signs of anyone else other than his own family—and those signs flashed loudly everywhere he turned. He went through the house, amazed again and again by how much remained exactly the same. Most of his mother’s books filled the walls, as neat and full as rows of corn, although some books were upside down and others stood in small stacks here and there throughout the rooms. The photographs along the top of the piano, on the bureaus and hanging on the stairwell, each one dusted clean and placed as he remembered them. In the bathroom there were even Amway and Shaklee products. His mom had been such a supporter of Snag, his dad would complain that the products were taking over the household; stacked five rows deep in the barn, the pantry, the cupboards. Enough, apparently, to last at least twenty years.

He turned on the faucet. Pipes seemed to be in working order. In the pantry, garden vegetables—rhubarb and berry jams, dried mushrooms, canned salmon and meats. Tomato sauces, soups, sauerkraut, relishes. Potted herbs along the windowsill next to the old kitchen table. He went down into the root cellar, stocked with boxes of potatoes and onions, hanging red cabbages and some dried fish and meat. Carved tally marks all over the wall. He didn’t count them, but it looked like it could be enough to account for ten years. Or a lot of dead buried bodies. The family’s old refrigerator held frozen fish and meats. Dried herbs hung from the ceiling.

Undoubtedly someone helped her with all of this. And who paid the electricity bill?

He climbed back up to the main floor, hesitated before heading up to the second floor. This was his house. He had every right to look around. But he paused again before he entered his mother and father’s room. The pauses came with a sense of reverence, as if he were entering a church or a museum. Everything—every single thing—in the entire house had been so well tended, so obviously respected by this Nadia.