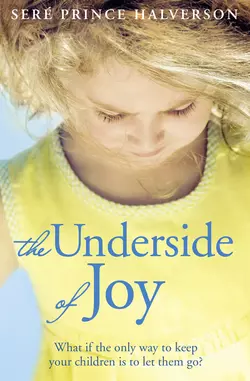

The Underside of Joy

Seré Prince Halverson

What if the only way to keep your children is to let them go? Perfect for all fans of Jodi Picoult.Losing a husband is unbearable. But losing her children too would be one heartbreak too many…Ella is happily settled in family life with her husband Joe and their two young children, Zach and Annie. Then the unthinkable happens – Joe is killed in a tragic accident.Distraught, Ella’s only solace is the children, who she clings to for dear life. But she can’t help feeling that the happiness she took for granted is over for good. Her worst fears are realised when Joe’s beautiful ex-wife Paige, who deserted her family three years earlier, turns up at his funeral, determined to reclaim her children.Struggling with her own grief, Ella is now forced to battle for her family and the life which she loves. And when pushed to the limits, Ella must decide who is the best mother for her children.

SERÉ PRINCE HALVERSON

The Underside of Joy

Dedication (#ulink_da996468-7c26-501f-acaf-163f965cc79c)

For Stan

Contents

Cover

Title Page (#u6192e644-731f-5751-866a-a67402faaedd)

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Epilogue

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_24085d55-ccb3-582c-8b20-fc77f6a6171d)

I recently read a study that claimed happy people aren’t made. They’re born. Happiness, the report pointed out, is all about genetics – a cheerful gene passed merrily, merrily down from one smiling generation to the next. I know enough about life to understand the old adage that one person can’t make you happy, or that money can’t buy happiness. But I’m not buying this theory that your bliss can be only as deep as your gene pool.

For three years, I did backflips in the deep end of happiness.

The joy was palpable and often loud. Other times it softened – Zach’s milky breath on my neck, or Annie’s hair entwined in my fingers as I braided it, or Joe humming some old Crowded House song in the shower while I brushed my teeth. The steam on the mirror blurred my vision, misted my reflection, like a soft-focus photograph smoothing out my wrinkles, but even those didn’t bother me. You can’t have crow’s-feet if you don’t smile, and I smiled a lot.

I also know now, years later, something else: The most genuine happiness cannot be so pure, so deep, or so blind.

On that first dawn of the summer of ’99, Joe pulled the comforter down and kissed my forehead. I opened one eye. He wore his grey sweatshirt, his camera bag slung over his shoulder, his toothpaste and coffee breath whispering something about heading out to Bodega before he opened the store. He traced the freckles on my arm where he always said they spelled his name. He’d say I had so many freckles that he could see the letters not just for Joe, but for Joseph Anthony Capozzi, Jr – all on my arm. That morning he added, ‘Wow, junior’s even spelled out.’ He tucked the blanket back over me. ‘You’re amazing.’

‘You’re a smart-ass,’ I said, already falling back to sleep. But I was smiling. We’d had a good night. He whispered that he’d left me a note, and I heard him walk out the door, down the porch steps, the truck door yawning open, the engine crowing louder and louder, then fading, until he was gone.

Later that morning, the kids climbed into bed with me, giggling. Zach lifted the sun-dappled sheet and held it over his head for a sail. Annie, as always, elected herself captain. Even before breakfast, we set out across an uncharted expanse, a smooth surface hiding the tangled, slippery underneath of things, destination unknown.

We clung to each other on the old rumpled Sealy Posturepedic, but we hadn’t yet heard the news that would change everything. We were playing Ship.

By their pronouncements, we faced a hairy morning at sea, and I needed coffee. Badly. I sat up and peeked over the sail at them, both their spun-gold heads still matted from sleep. ‘I’m rowing out to Kitchen Island for supplies.’

‘Not when such danger lurks,’ Annie said. Lurks? I thought. When I was six, had I even heard of that word? She bolted up, hands on hips while she balanced on the shifting mattress. ‘We might lose you.’

I stood, glad that I’d thought to slip my underwear and Joe’s T-shirt back on before I’d fallen asleep the night before. ‘But how, dear one, will we fight off the pirates without cookies?’

They looked at each other. Their eyes asked without words: Before breakfast? Has she lost her mind?

Cookies before breakfast . . . Oh, why the hell not? I felt a bit celebratory. It was the first fogless morning in weeks. The whole house glowed with the return of the prodigal sun, and the worry that had been pressing itself down on me had lifted. I picked up my water glass and the note Joe had left underneath it, the words blurred slightly by the water ring: Ella Bella, Gone to capture it all out at the coast before I open. Loved last night. Kisses to A&Z. Come by later if . . . but his last words were puddled ink streaks.

I’d loved the previous night too. After we’d tucked the kids in, we talked in the kitchen until dark, leaning back against the counters, him with his hands deep in his pockets, the way he always stood. We stuck to safe topics: Annie and Zach, a picnic we’d planned for Sunday, crazy town gossip he’d heard at the store – anything but the store itself. He threw his head back, laughing at something I said. What was it? I couldn’t remember.

We had fought the day before. After fifty-nine years in business, Capozzi’s Market was struggling. I wanted Joe to tell his dad. Joe wanted to keep pretending business was fine. Joe could barely tell himself the truth, let alone his father. Then he’d have a moment of clarity, tell me something about an overdue bill or how slow the inventory was moving, and I would freak out, which would immediately shut him back down. Call it a bad pattern we’d been following the past several months. Joe pushed off from the counter, came to me, held my shoulders, said, ‘We need to find a way to talk about the hard stuff.’ I nodded. We agreed that, until recently, there hadn’t been that much hard stuff to talk about.

I counted us lucky. ‘Annie, Zach. Us . . .’ Instead of tackling difficult topics right then, I’d kissed him and led him to our bedroom.

I feigned rowing down the narrow hall, stepping over Zach’s brontosaurus and a half-built Lego castle, until I was out of view, then stood in the kitchen braiding my hair in an effort to restrain it into single-file order down the back of my neck. Our house was a bit like my red hair – a mass of colour and disarray. We’d torn out the wall between the kitchen and living room, so, from where I stood, I could see the shelves crammed to the ceiling with books and plants and various art projects – a Popsicle-stick boat painted yellow and purple, a lopsided clay vase with Happy Mother’s Day spelled out in macaroni letters, the M long gone but leaving an indent in its place. Large patchworks of Joe’s black-and-white photographs hung in the few spaces that didn’t have built-ins or windows. One giant French window opened out to the front porch and our property beyond. The old glass made a feeble insulator, but we couldn’t bring ourselves to part with it. We loved its wavy effect on the view, as if we looked through water at the hydrangeas that lapped at the porch, the lavender field waiting to be harvested, the chicken coop and brambles of blackberries, the old tilted barn, built long before Grandpa Sergio bought the land in the thirties, and finally, growing across the meadow from the redwoods and oaks, the vegetable garden, our pride and glory. We had about an acre – mostly in the sun, all above the flood line, with a glimpse of the river if you stood in just the right spot.

Joe and I enjoyed tending the land, and it showed. But none of us, including the kids, were gifted at orderliness when it came to inside our home. I didn’t worry about it. My previous house – and life – had been extremely tidy, yet severe and empty, so I shrugged off the mess as a necessary side effect of a full life.

I took out the milk, then stuck Joe’s note on the fridge with a magnet. I’m not sure why I didn’t throw it out; it was probably the sweetness of the previous night’s reconciliation that I wanted to hang on to, the Ella Bella . . .

My name is Ella Beene, and as one might imagine, I’ve had my share of nicknames. Of all of them, Joe’s was one I downright cherished. I’m not a physical beauty – not ugly, but nothing near what I’d look like if I’d had a say in the matter. Yes, the red hair intrigues. But after that, things are pretty basic. I’m fair and freckled, too tall and skinny for some, with decent features – brown eyes, nice enough lips – that look better when I remember to wear makeup. But here’s the thing: I knew Joe liked the whole package. The inside, the outside, the in-between places, the whole five foot ten of me. And since all my nicknames fit me at their appointed times, I let myself bask in that one: Bella. So there I was. Thirty-five years old, beautiful in Italian, on a Saturday morning, making strong coffee, preparing a breakfast appetizer of cookies and milk for our children.

‘Cookies. Me want cookies.’ The sailors had jumped ship and were trying to make their eyes bulge, taking the glasses of milk from the kitchen counter and a couple of oatmeal squares. Our dog, Callie, a yellow Lab and husky mix who knew how to work her most forlorn expression, sat thumping her tail until I gave her a biscuit and let her out. I sipped my coffee and watched Annie and Zach shove cookies in their mouths, grunting, letting crumbs fly. This was the one thing Sesame Street taught them that I could have done without.

The sun beckoned us outside, so I asked them to hurry and get dressed, then went to pull on a pair of shorts and finally stick a load of darks into the washer. As I added the last pair of jeans, Zach ran in buck naked and held up his footed pyjamas. ‘I do it myself,’ he said. I was impressed he hadn’t left them in the usual heap on the floor, and I picked him up so he could drop in his contribution. His butt was cool against my arm. We watched until the agitator sucked the swirl of fire trucks and blue fleece below into the sudsy water. I set him down and he careened out, his feet slapping down the wood hall. Except for shoe-lace tying, which Zach was still a few years from, both kids had become alarmingly self-sufficient. Annie was more than ready for first grade, and now Zach for preschool, even if I wasn’t quite ready for them to go.

This would be a milestone year: Joe would save the sinking grocery store that had been in his family for three generations. I would go back to work, starting a new job in the fall as a guide for Fish and Wildlife. And Annie and Zach would zoom out the door each morning on their ever-growing limbs, each taking giant leaps along that ever-shortening path of their childhood.

When I first met them, Annie was three and Zach was six months. I had been on my way from San Diego to a new life, though I wasn’t sure where or what it would be. I’d stopped in the small, funky town of Elbow along the Redwoods River in Northern California. The town was named for its location on the forty-five-degree bend in the river, but locals joked that it was named for elbow macaroni because so many Italians lived there. I planned to get a sandwich and an iced tea, then maybe stretch my legs and walk down the path I’d read about to the sandy beach along the river, but a dark-haired man was locking up the market. A little girl squirmed out of his grasp while he tried to get the key in the lock and balance a baby in his other arm. She pulled loose and raced out towards me, into my legs. Her blonde head grazed my knees, and she laughed and reached her arms to me. ‘Up.’

‘Annie!’ the man called. He was lean, a bit dishevelled and anxious, but significantly easy on the eyes.

I asked him, ‘Is it okay?’

He grinned relief. ‘If you don’t mind?’ Mind? I scooped her into my arms and she started playing with my braid. He said, ‘The kid doesn’t have a shy bone in her body.’ I could feel her chubby legs secured around my hips, could smell Johnson’s baby shampoo, cut grass, wood smoke, a hint of mud. A whisper of grape juice-stained breath brushed my cheek. She’d held my braid tight in her fist but she hadn’t pulled.

Callie barked and, from the kitchen, I saw Frank Civiletti’s police cruiser. That was odd. Frank knew Joe wouldn’t be home. They’d been best friends since grade school, and they always talked over morning coffee at the store. I hadn’t heard Frank coming, but there he was, slowly heading up the drive, his tires popping gravel. Also odd. Frank never drove slowly. And Frank always turned his siren on when he made our turn from the main road. His ritual for the kids. I looked at the microwave clock: 8:53. Already? I picked up the phone, then set it down. Joe hadn’t called when he got to the store. Joe always called. ‘Here.’ I grabbed the egg baskets and handed them to the kids. ‘Check on the Ladies and bring us back some breakfast.’ I opened the kitchen door and watched them run down to the coop, waving and calling out, ‘Uncle Frank! Turn on your siren.’

But he didn’t; he parked the car. I stood in the kitchen. I stared at the compost bucket on the counter. Coffee grounds Joe had used that morning, the banana peel from his breakfast. The far edges of my happiness began to brown, then curl.

I heard Frank’s door open and shut, his footsteps on the gravel, on the porch. His tap on the front door’s window. Annie and Zach were busy collecting eggs at the coop. Zach let out a string of laughter, and I wanted to stop right there and wrap it around our life so we could keep it intact and whole. I forced myself out of the kitchen, down the hall, stepping over the toys still on the floor, seeing Frank through the paned watery glass stare down at a button on his uniform. Look up and give me your Jim Carrey grin. Just walk in, like you usually do, you bastard. Raid the fridge before you say hello. Now we stood with the door between us. He looked up with red-rimmed eyes. I turned, headed back down the hallway, heard him open the door.

‘Ella,’ he said, behind me. ‘Let’s sit down.’

‘No.’ His footsteps followed me. I waved him away without turning to see him. ‘No.’

‘Ella. It was a sleeper wave, out at Bodega Head,’ he said to my back. ‘It rose out of nowhere.’

He told me Joe was shooting the cliff out on First Rock. Witnesses said they shouted a warning, but he couldn’t hear them over the wind, the ocean. It knocked him over and took him clean. He was gone before anyone could move.

‘Where is he?’ I turned when Frank didn’t answer. I grabbed his collar. ‘Where?’

He glanced down again, then forced his eyes back on me. ‘We don’t know. He hasn’t shown up yet.’

I felt a small hope look up, start to rise. ‘He’s still alive. He is! I need to get out there. We need to go. I’ll call Marcella. Where’s the phone? Where are my shoes?’

‘Lizzie’s already on her way over to pick up the kids.’

I ran towards our bedroom, stepped on the brontosaurus, fell hard on my knee, pushed myself back up before Frank could help me.

‘Listen, El. I would not be saying any of this to you if I thought there was a chance he was alive. Someone even said they saw a spray of blood. We think he hit his head. He never came up for air.’ Frank said something about this happening every year, as if I were some out-of-towner. As if Joe were.

‘This doesn’t happen to Joe.’

Joe could swim for miles. He had two kids that needed him. He had me. I dug in the closet for my hiking boots. Joe was alive and I had to find him. ‘A little blood? He probably scraped his arm.’ I found the boots, pulled the comforter off the bed. He would be freezing. I grabbed the binoculars from the hall tree. I opened the screen door and stepped out on the porch, tripping on the dragging blanket. I called back, ‘Am I driving myself ? Or are you coming?’

Frank’s wife, Lizzie, loaded Zach into their Radio Flyer wagon with their daughter, Molly, while Annie stuck her arm through the handle and shouted through her cupped hands, ‘We’re taking the rowboat to shore. Watch for pirates.’

I waved and tried to sound cheerful. ‘Got it. Thanks, Lizzie.’ She nodded, solemn. Lizzie Civiletti was not my friend; she’d told me that, soon after I came to town. And yet neither was she unkind. She would protect the kids from any telltale signs of panic. As much as I wanted to go to them, to gather them up to me, I smiled, I waved again, I blew kisses.

Chapter Two (#ulink_2c770344-c93f-5333-9cd9-fab14e72ced5)

Frank drove the winding road with his lights spinning circles. I closed my eyes, didn’t look at the rolling hills I knew would be shimmering, dotted with what Joe called the ‘Extremely Happy California Cows.’ He’s fine. He’s fine! He’s disoriented. He hit his head. He’s not sure where he is. A concussion, maybe. He’s wandering the beach at Salmon Creek. That’s it! The wave pulled him out and dashed him down the coast a ways, but there he is. He’s talking to some high school boys. They have surfboards. Dude. Did you ride that gnarly wave? They’ve built a fire even though the signs prohibit it. They offer him beer and hot dogs. They forgot the buns, but here’s mustard. He’s famished. He has a flash of memory. It all comes back to him.

Us. Making up. Just the night before. Standing in the kitchen, easing our way back together, then falling into bed, relieved. We were lousy fighters, but we could win medals for making up. He had kissed my stomach in a southbound line until I moaned, kissed my thighs until I whimpered, until we both gave in. Later, as I drifted off, he propped himself up on his elbow and looked down at me. ‘I have something I need to tell you.’

I tried to fight the pull of sleep. ‘You want to talk? Now?’ It was a noble effort to be more open, but, Jesus, right after sex? Wasn’t that womankind’s most annoying tactic? So I was a man about it and said, ‘You can’t go and get me this blissed out and then tell me we have to talk.’ I figured it was more bad news about the store.

‘Fair enough,’ he said. ‘Tomorrow, then. We’ll make it a date. I’ll see if Mom will take the kids.’

‘Ooooh. A date.’ Maybe it wasn’t about the store. Hell, I thought. Maybe it’s good news.

He smiled and touched my nose. I hadn’t said, No, we have to talk now. I hadn’t fretted. I had immediately fallen asleep.

So, no. Joe could not be dead. He was eating hot dogs and drinking beer and talking surfing. He still needed to talk to me about something. I opened my eyes.

Frank sped through Bodega Bay – with its seafood restaurants and souvenir shops, the pink-and-white-striped saltwater taffy store the kids could never get past without insisting we stop – along the curved bayside road and its hand-painted sandwich signs advertising the latest catch, the air a mingle of smoked salmon and sea and wildflowers, up the curved ridge to Bodega Head, Joe’s favourite place on the planet.

There was the trailhead to the hike we’d taken so many times, along the cliff. On one side the sea down below, on the other a prairie of shore wildflowers – with the yarrow, or Achillea borealis, the sand verbena, or Abronia umbellate – down to the grassy dunes. Joe was always impressed with my ability to not only identify the birds and wildflowers, but rattle off their Latin names too, a gift I’d inherited from my father.

The parking lot was full, including several sheriff’s cars, a fire truck, paramedics, and there at the end by the trail, Joe’s old truck. He called it the Green Hornet. I grabbed the binoculars, got out of Frank’s cruiser, and slammed the door. A helicopter headed north, following the shoreline, its blades thumping, a thunderous, too-rapid heartbeat fading away.

I had no jacket, and the wind whipped against my bare arms, burned my eyes. Frank draped the comforter around me. I said, ‘Please don’t make me talk to anyone.’

‘You got it.’

‘I need to go alone.’ He pulled me into his side, then released me. I walked to Joe’s truck. Unlocked, of course. His blue down jacket, stained and worn in, just the way he liked it. I slipped it on. Warm from the sun. I left the blanket in the car so it would be warm for him too. His thermos lay on the floor. I shook it: empty. I lifted the rubber mat and saw his keys, as I knew I would, and stuck them in my pocket.

Through the binoculars the water flashed a multitude of lights, as if taking pictures of its own crime scene.

In March and April, we’d packed a picnic and brought the kids out to watch for whales. We’d searched the horizon with the same binoculars, marvelled at the grey whales’ graceful sky hopping and breaching. We told the kids the story of Jonah and the whale, how one minute Jonah was tossed overboard into the sea, and the next minute swallowed by the whale, along for the ride. Annie rolled her eyes and said ‘Yeah. Riiiiight.’ I’d laughed, confessed to them that even when I was a little kid in Sunday school, I’d found the story hard to swallow.

But now I was willing to believe anything, to pray anything, to promise anything. ‘Please, please, please, please . . .’

I headed down the lower trail, seeing Joe taking each step, strong, alive. An easy climb up First Rock, the white water swirling far below, unthreatening. But you broke your own rule, Joe, didn’t you? The one you always told me and Annie and Zach: Never turn your back on the ocean. The Coast Guard boat moved steadily, not stopping. I glanced over my shoulder at the cliff. It looked like the clenched fist of God, the clinging reddish sea figs its scraped and bleeding knuckles. Please, please. Tell me where he is.

I climbed down the rock. The sun’s reflection off the water made me wince. Farther down, I saw it wasn’t the water, but metal wedged deep between two other rocks. I stepped over to investigate. Was it . . .? I scrambled down closer. There, waiting for me to notice it, lay Joe’s tripod. His camera was gone.

Wait. That’s it. That’s what he’s doing. He’s hunting for his camera. He’s sick about it. He’s in the dunes somewhere, lost. All those deer trails, confusing, every dune starts to look the same and it’s hard to tell what you’ve covered and the wind is whipping and you’re tired and you have to lie down. So cold. A doe watches tentatively but she senses your desperation and she approaches, lies down to warm you and she licks the salt off your nose.

You are fine! You’re just trying to find your way back. ‘Don’t be angry,’ you’ll say, wiping my tears with your thumbs, holding my face to yours, your fingers locked in my hair. ‘I’m so sorry,’ you’ll say. I’ll shake my head to tell you all is forgiven, thank you for fighting that wave, thank you for coming back to us. I’ll bury my nose in your neck, the salt will rub off on my cheek. You’ll smell like dried blood and fish and kelp and deer and wood smoke and life.

I wandered the dunes past dark, long after they called off the search for the day. The half-moon disclosed nothing. Frank said even less. Usually he never shut up.

Joe’s Green Hornet sat empty, the only vehicle in the parking lot other than Frank’s cruiser. I wanted to leave the truck for Joe, so I unlocked it, replaced the keys under the mat. I slipped off his jacket and left that for him too, along with the blanket.

I climbed in with Frank, quiet, as the dispatcher gave an address for a domestic dispute. I wanted to be with the kids but I didn’t want my face to let on, to drive a spike through their contented unknowing.

Frank offered to keep Joe’s parents and extended family away at least until morning. I nodded. I couldn’t hear his parents or brother or anyone else cry, couldn’t hear anything that would acknowledge defeat. We needed to focus on finding him.

Once home, I called the kids. ‘Are you having fun?’ I asked Annie.

‘Oh yes,’ she said. ‘Lizzie let us take off all the cushions on all the furniture and build a house. And she said we can even sleep in it tonight.’

‘Too cool. So you want to spend the night?’

‘I think we better. Molly will only sleep out here if I’m with her. You know Molly.’

‘Yeah, then you better.’

‘Night, Mommy. Can I talk to Daddy?’

I leaned over, pulled the lace on my boot, swallowed, forced my voice to sound light. ‘He’s not here yet, Banannie.’

‘Okay, well then, give him this.’ I knew she was hugging the phone. ‘And this one’s for you . . . Bye.’

Zach got on the line just long enough to say, ‘I muchly love you.’ I hung up, kept sitting on the couch. Callie lay down at my feet and let out a long sigh. The hall light picked up objects in the dark room. I’d set up Joe’s tripod in the corner to welcome him. Its three legs, its absent camera now seemed a terrible omen. I stared at the Capozzi family clock ticking on the end table. Yes. No. Yes. No. I opened the glass. The swinging pendulum: this way. That way. I stuck my finger in to stop it. Silence. My fingertip steered the hour hand backward, back to that morning, when this time I felt Joe stretching awake, kissed the soft hair on his chest, grabbed his warm shoulder, said, ‘Stay. Don’t go. Stay here with us.’

The next day a Swiss tourist found Joe’s body, bloated and wrapped in kelp, as if the sea had mummified him in some feeble attempt at apology. This time I opened the door for Frank and hugged him before he could speak. When he leaned back, he just shook his head. I opened my mouth to say No but the word sank, soundless.

I insisted on seeing him. Alone. Frank drove me to McCready’s and stood beside me while a grey-haired woman with orange-tinted skin explained that Joe wasn’t really ready to be viewed.

‘Ready?’ A strange, high-pitched laugh eked past the lump in my throat.

Frank tilted his head at me. ‘Ella . . .’

‘Well? Who the hell is ever ready?’

‘Excuse me, young –’ But then she shook her head, reached out and took both my hands in hers, said, ‘Come this way, dear.’ She ushered me down a carpeted hallway, past the magnolia wallpaper and mahogany wainscoting, from the noble facade to the laboratorial back rooms, the hallway now flecked green linoleum, chipped in places, unworthy of its calling.

How could this be? That he lay on a table in a cooled room that resembled an oversize stainless-steel kitchen? Someone had parted his hair on the wrong side and combed it, perhaps to hide the wound on his head, and they covered him up to his neck with a sheet – that was it. I took off my jacket and tucked it over his shoulders and chest, saying his name over and over.

They had closed his eyes, but I could tell the way his lid sunk in that his right eye was missing.

I used to tell him his eyes were satellite pictures of Earth – ocean blue with light green flecks. I joked that he had global vision, that I saw the world in his eyes. They could go from sorrow to teasing mischief in three seconds flat. They could pull me from chores to bed in even less time. Their sarcastic roll could piss me off, too, in no time at all.

His amazing photographer’s eye with its unique take on things – where had it gone? Would Joe’s vision live on soaring in a gull or scampering sideways in a nearsighted rock crab?

His hair felt stiff from the salt, not soft and curly through my fingers. I pushed it over to the right side. ‘There, honey,’ I said, wiping my nose on my sleeve. ‘There you go.’ His stubbled face, so cold. Joe had a baby face that he needed to shave only every three or four days, his Friday shadow. He said he couldn’t possibly be Italian; he must have been adopted. He’d rub his chin and say, ‘Gotta shave every damn week.’

He was handsome and sexy in his imperfection. I ran my finger down his slightly crooked nose, along the ridge of his slightly big ears. When we first met, I’d guessed correctly that he’d been an awkward teenager, a late bloomer. He had an appealing humility that couldn’t be faked by the men who’d managed to start breaking girls’ hearts back in seventh grade. He was always surprised that women found him attractive.

I slipped my hand under the sheet and held his arm, so cold, willed him to tense the thick ropes of muscles that ran their length, to laugh and say in his grandmother’s accent: You like, Bella? Instead, I could almost hear him say, Take care of Annie and Zach. Almost, but not quite.

I nodded anyway. ‘Don’t worry, honey. I don’t want you to worry, okay?’

I kissed his cold, cold face and laid my head on his collapsed chest, where his lungs had filled with water and left his heart an island. I lay there for a long time. The door opened, then didn’t close. Someone waiting. Making sure I didn’t fall apart. I would not fall apart. I had to help Annie and Zach through this. I whispered, ‘Good-bye, sweet man. Good-bye.’

I don’t even pretend to know what might happen to us after we die because the possibilities are endless. I have a degree in biology and feel most at home in nature, yet I’m confounded by human nature, by those things that cannot be observed and named and catalogued, a woman of science who slogs off the trail into mystery and ponders at the feet of folklore. So I often wonder if Joe had watched us that morning while we were playing Ship, in those bridging moments between before and after. Had he watched us from the massive redwoods he so revered, then from a cloud? Then from a star? The photographer in him would have delighted in the different perspectives, this after-a-lifetime chance to see that which is too deep and wide to be contained by any frame. Or was that him, that male fuchsia-throated Anna’s Hummingbird, Calypte anna, that hung around for days? He flittered inches from my nose when I sat on our porch, so close, I could feel his wings beating air on my cheek.

‘Joe?’ He took off suddenly, making giant swoops like handwriting in the sky. I know the swoops are part of their impressive mating ritual. And yet now I can’t help wondering if it was Joe, panicked, attempting to write me a message, frantically trying to tell me his many secrets, to warn me of all that he’d left unsaid.

Chapter Three (#ulink_c2d1be19-16d0-53d3-83db-cc0a87911346)

Frank drove me home from McCready’s, then left to pick up the kids. I sat at our kitchen table, staring at the pepper grinder. A wedding gift from someone . . . a college friend of mine, I think. Joe had made a big deal about that gift, thought it was the perfect pepper grinder, and I’d made fun of him, said, ‘Who knew? That there was a perfect pepper grinder out there and that we would be so lucky as to be its proud owners?’

Zach and Annie pranced onto the porch, in the front door. Their singsong Mommymommymommy! broke through to me, through my new watery, subdued world, and with them, a slicing clarity. I forced myself up, upright, steady. I said their names. ‘Annie. Zach.’ Joe told me once that they were his A to Z, his alpha and omega. ‘Come here, guys.’ Frank stood behind them. I knew what I had to say. I would not try to sugarcoat this, like my relatives had with me when I was eight and my own father died. I would not say that Joe had fallen asleep, or had gone to live with Jesus, or was now an angel, dressed in white with feathered wings. It would have helped if I’d had a belief system, but my beliefs were in a misshapen pile, constantly rearranging themselves, as unfixed as laundry.

Annie said, ‘What happened to your knee?’

I touched it but couldn’t feel the bruise from the fall I’d taken in the hallway only a day ago.

‘You better get a Band-Aid.’ She gave me a long look.

I knelt down on my other knee. I pulled both of them to me and held on. ‘Daddy got hurt.’ They waited. Frozen. Silent. Waiting for me to reassure them, to say where he was, when they could kiss him. When they could make him a get-well-soon card and put it on the breakfast tray. Say the words. They have to hear them from you. Say them: ‘And he . . . Daddy . . . he died.’

Their faces. My words were carving themselves into their sweet, flawless skin. Annie started to cry. Zach looked at her, then sounding somewhat amused, said, ‘No, he didn’t!’

I rubbed his small back. ‘Yes, honey. He was at the ocean. He drowned.’

‘No way, José. Daddy swims fast.’ He laughed.

I looked up to Frank, and he knelt down with us. ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘Daddy is a good swimmer . . . Daddy was. But listen to me, Zach, okay? A big wave surprised him and knocked him off the rock. Maybe he bumped his head; we don’t know.’

Annie wrung her hands and cried, ‘I want my daddy. I want my daddy!’

I whispered into her hair, ‘I know, Banannie, I know you do.’

Zach turned to Frank. ‘It’s not true. He’ll swim back, won’t he, Uncle Frank?’

Frank ran his hand over his crew cut, covered his eyes for an instant, sat back on his heels, and took Zach onto his lap. He held him. He said, ‘No, buddy. He’s not coming back.’ Zach whimpered against Frank’s chest, then flung himself backward while Frank maintained his hold. Zach let out a howl that rang with the rawness of unfathomable loss.

I don’t remember what happened next, or I should say, I don’t remember the sequence of things. It seems that at once our long gravel driveway filled with cars, the house and yard with people, the fridge with chicken cacciatore, eggplant Parmesan, lasagna. Joe’s family took up most of the house. My extended family was just my mom, and she was still on a plane from Seattle. In a strange, sad way, the day reminded me of our wedding two years before, the last time all these people had caravanned up our drive, gathered together, and brought food and drink.

Joe’s family was loud – as they had been in the celebration of our marriage, and now in mourning, even in the early hours of disbelief. His great-aunty, already draped in black, was the only family member who still spoke Italian. She beat her shrivelled bosom and cried out, ‘Caro Dio, non Giuseppe.’

And then periods of stunned silence washed into the room while each person sat, anchoring his or her eyes on a different object – a lamp, a coaster, a shoe – as if it held an answer to the question, Why Joe?

His uncle Rick poured stiff drinks. His father, Joe Sr, drank many of those drinks and began cursing God. His mother, Marcella, held Annie and Zach in her large lap and said to her husband, ‘Watch your language, Joseph. Your grandchildren are in the room and Father Mike will be walking in that door any goddamned second.’

I sat in Joe’s favouurite chair, the old leather one handed down from Grandpa Sergio. Annie and Zach climbed up on me, curling themselves under my arms, the gravity of their small bodies like perfect paperweights, keeping me securely in place. Joe’s brother, David, kept calling from his cell phone in tears, as he and Gil, his partner, inched along in traffic on the 101.

Later, while the kids napped, David found me in the bathroom. He said through the door, ‘Sweetie, are you peeing or crying or both?’ Neither. I had stolen away for a few minutes and was staring at myself in the mirror, wondering how everything on my face was still as it always had been. My eyes sat in their assigned places above my nose, my mouth below it. I unlocked the door. He came in, shut the door. His arms hung at his sides, palms towards me. His face was ravaged and unshaven, but he was, as always, utterly beautiful; his Roman features so perfectly chiselled and his body so carved that his friends referred to him as The David. We leaned into each other. He whispered, ‘What are we going to do without him?’ I shook my head and let my nose run onto his shoulder.

That night, in bed with each arm around a sleeping child, my tears slipping back into my ears, I wondered how we’d get through this. But I reminded myself that I’d survived another grief that had threatened to undo me.

I had come to think of my seven-year marriage to Henry as The Trying Years. Trying to push a boulder up a hill. Trying to push Henry’s lackadaisical sperm up to my uterus. Trying to coax my stubborn eggs through my maze of fallopian tubes. The urgent phone calls to Henry to meet me at home for lunch. The awkwardness of sex on demand. And afterwards, lying on my back with my feet in the air, I’d will egg and sperm to Meet! Mingle! Hook up! (I was convinced by then that my eggs had shells, that I had tough eggs to crack.) I wanted children so badly that the want spread itself over me and took me hostage; it tied me up in it so that my days became as dark and knotted as I imagined my uterus to be: a scary, uninviting hovel.

Then I finally got pregnant.

And then I lost the baby.

I lay on the couch with old towels underneath me and listened to Henry make the phone calls in the kitchen, feeling as inadequate as the terminology implied. I lost the baby – like keys, or a mother-of-pearl earring. Or spontaneous abortion, which sounded like all of a sudden we didn’t want the baby, like we had made a quick, casual choice. And then there was miscarriage. The morphing of a mistake and a baby carriage.

More trying. Trying to get pregnant, trying to stay pregnant. Trying shots, gels, pills, hope, elation, bed rest, more bed rest. In the end, despair.

Again. And again and again and again. Five in all.

And then one Easter morning – while the neighbourhood kids ran up and down the dwarfed aprons of lawns, their voices pealing with sugared-up joy, wearing new pastel clothes and chocolate smears on their faces, filling their baskets with a plethora of eggs – Henry and I sat at our long, empty dining room table and decided to quit. We quit trying to have a baby and we quit trying to have a marriage. Henry was the one who was courageous enough to put it into words: There was no us left apart from our obsession, and perhaps that’s why we’d kept at it with such tenacity.

At that time, it seemed I would always be sad. Little did I know that the universe was about to shift just six months later, when I drove through Sonoma County and took the winding road someone had aptly named the Bohemian Highway. ‘Good-bye, Bio-Tech Boulevard!’ I shouted to the redwoods, which crowded up to the road like well-wishers greeting my arrival. At the bridge, I waited as a couple of young guys with dreadlocks, wearing guitars on their backs, crossed over to head down to the river’s beach, and they waved like they’d been expecting me. I turned into Elbow and stopped at Capozzi’s Market. Good-bye, Sadness in San Diego.

Joe and I were the same height; we saw things eye to eye. We slipped into each other’s lives as easily as Annie’s hand slipped into mine that evening in front of the store. We didn’t sleep together on our first date. We didn’t wait that long. I followed him home from the parking lot, helped him change diapers and feed baby Zach and tell Annie a story and kiss them good night, as if we’d been doing the same thing every night for years. Though neither of us was pitiful enough to whisper the cliché that we usually didn’t do that sort of thing, we both admitted later that we usually didn’t. But the deepest wounds have a tendency to seep recklessness. He helped me carry in my suit-case, found a vase for a bucket of cornflowers – my Centaurea cyanus that I’d set on the passenger-side floor, brought along for good luck. We talked until midnight, and I learned that the wife whose paisley robe still hung from the hook on the bathroom door had left him for good four months before, that her name was Paige, that she had called only once to check on Annie and Zach. She never called in the three years that followed. Not once. We made love in Paige and Joe’s bed. Yes, it was needy sex. Amazing needy sex.

But now I lay in bed thinking, All I want to do is go back. ‘We want you back,’ I whispered. I slipped my arms out from under Annie’s and Zach’s heavy heads and tiptoed into the bathroom. There was Joe’s aftershave, Cedarwood Sage. I opened it and inhaled it, dabbed it on my wrists, behind my ears, along the lump in my throat. His toothbrush. His razor. I ran my finger along the blade and watched the fine line of blood appear, mixing with tiny remnants of his whiskers.

I turned on the basin taps so the kids wouldn’t hear me. ‘Joe? You gotta come back. Listen to me. I can’t fucking do this.’ The sleeper wave had come out of nowhere, and now I felt that wave in the bathroom, the inability to breathe, fighting the thunderous slam that ripped away Joe . . . Annie and Zach’s daddy. They’d already been abandoned by their birth mother. How much could they take? I had to pull it together for them. But at the same time I knew that their very existence would help hem me in, keep all my parts together.

I dried my face and took a few deep breaths and opened the door. Callie pressed her cold black nose into my hand, turned and thumped me with her tail, licked my face when I bent to pet her back. I wanted to be there for the kids when they woke, so I climbed back into bed and waited for the sun to rise, for their eyes to open.

Annie stood on a stool, cracking eggs. Joe’s mom was going at my fridge with a spray bottle, the garbage can full of old food. I went over and hugged Annie from the back. The yolks floated in the bowl, four bright, perfect suns. She broke them with a stab of the whisk and stirred them with concentrated vigour.

She turned to me and said, ‘Mommy? You’re not going to die, are you?’

There it was. I touched my forehead to hers. ‘Honey, someday I will. Everyone does. But first, I’m planning on being around for a long, long time.’

She nodded, kept nodding while our foreheads bobbed up and down. Then she turned back to her eggs and said, ‘Are you, you know, planning on leaving anytime soon?’

I knew exactly what she was thinking. Whom she was thinking about. I turned her back around. ‘Oh, Banannie. No. I will never leave you. I promise. Okay?’

‘You promise? You pinkie promise?’ She held out her pinkie and I looped mine in hers.

‘I more than pinkie promise. I promise you with my pinkie and my whole big entire self.’

She wiped her eyes and nodded again. She went back to whisking.

People kept arriving and fixing things: the unhinged door on the chicken coop, the fence post that went down in a storm months before; someone was changing the oil in the truck. Who had driven it home from Bodega Bay? Who had put Joe’s jacket back on the hook, and the blanket back on our bed, and when? The drill started going again. The house smelled like an Italian restaurant. How could anyone eat? David, the writer in the family, who was also one helluva cook, was working on the eulogy out on the garden bench he’d given us for our wedding, while some of his culinary masterpieces graced the table. Everyone seemed to be doing something constructive except me. I kept telling myself that I had to be strong for the kids, but I didn’t feel strong.

My mom, who’d arrived from Seattle, hadn’t let Zach out of her sight and was digging in the dirt with him and his convoy of Tonka trucks and action figures. Joe’s mom and Annie kept busy cleaning, stopping to wipe each other’s tears, then going back to wiping any surface they could find. I found myself wandering back and forth between Annie and Zach, drawing them in for a hug, a sigh, until they would slip down off my lap and back into their activities.

While she cleaned, Marcella sang. She always sang; she was proud of her voice, and rightly so. But she never sang Sinatra or songs from her generation; she sang songs from her kids’ generation. She loved Madonna, Prince, Michael Jackson, Cyndi Lauper – you name a song from the eighties and she could sing it. Joe and David had told me that when they were teenagers, blaring stereos from their bedrooms, Marcella would shout up from the kitchen, ‘Kids! Turn that crap up!’

While she scoured the grimy tile grout in my kitchen with a toothbrush, she started singing in an aching soprano: ‘Like a virgin . . . for the very first time.’ I let out a strange, sharp laugh and she looked at me, shocked. ‘What, sweetie? You okay?’ She hadn’t intended to make a crack at my housekeeping, was so preoccupied with sadness that she didn’t even realize what she was singing. But I knew Joe would have got a kick out of it, that on another day, in another layer of time, we both would have pointed out the lyrics, laughed, and teased her. She would have responded by swaying her big bottom back and forth, adding, ‘Oh yeah? Take this: The kid is not my son . . .’ But instead she searched me for further signs of grief-stricken insanity to accompany my shriek of laughter. I shook my head and waved to say, Never mind. She took my face in her thick hands. ‘Thank God my grandchildren have you for their mother. I thank God every day for you, Ella Beene.’ I reached my arms around the massive trunk of her.

‘Why don’t you sit down?’ I said, then started to take the spray bottle from her hand. ‘Rest. Let me pour you a cup of coffee.’

She pulled it back. ‘No. This is what I do. This is all I can do. Resting, it makes it worse for me.’

I nodded, hugged her again. ‘Of course.’ Marcella always believed in the clarity of Windex.

The next morning, I slid my black dress from its dry-cleaning bag and lifted my arms and felt the cool lining slip over my head. I considered slipping into the plastic instead, letting it tighten against my nostrils and mouth, and letting them lay me in the same dark hole with Joe. It was the thought of the kids that helped me push my feet into the black slings my best friend, Lucy, bought me –’You cannot wear Birkenstocks to a funeral, my dear, even in Northern California’ – and find both of the silver and aquamarine drop earrings Joe gave me our first Christmas together.

At the church, thirty-six people spoke. We cried, but we laughed too. Most of the stories went back to the time before I knew Joe. It seemed odd that almost everyone in the church had known him much longer than I had. I was the newcomer among them, but I found a certain comfort in telling myself that they didn’t know Joe the way I did.

Afterwards, I remembered having conversations I couldn’t quite hear and receiving hugs I couldn’t quite feel – as if I’d wrapped myself in plastic after all. The only thing I could feel was Annie’s and Zach’s hands slipping into mine, the solidity of their palms, the pressings of their small fingers, as we walked out of the church, as we stood at the grave site on the hill, as we walked down towards the car. And then Annie’s hand pulled out of mine. She walked up to a striking blonde woman I didn’t know, standing at the edge of the cemetery. Perhaps one of Joe’s old classmates, I thought. The woman bent down and Annie reached out, lightly touched her shoulder.

‘Annie?’ I called. I smiled at the woman. ‘She doesn’t have a shy bone in her body.’

The woman took Annie’s other hand in both of hers, whispered in her ear, and then spoke to me over her shoulder. ‘Believe me, I know that. But Annie knows who I am, don’t you, sweet pea?’

Annie nodded without pulling her hand away or looking up. She said, ‘Mama?’

Chapter Four (#ulink_22ee5663-5816-5a81-9ba5-5ee03a06fa1b)

Annie had called her Mama. She and Zach called me Mom and Mommy. But not Mama. Never Mama. I’d never questioned it, or really even thought of it, but the distinction rang out in that cemetery: Mama is the first-word-ever-uttered variety of mother. The murmur of a satisfied baby at the breast.

I recognized Paige then. I’d once found a picture of her, gloriously pregnant, that had been stuck in a book on photography entitled Capturing the Light – it was the one photo Joe had forgotten, or maybe had intended to keep, when he purged the house of her. I was astounded at her beauty and said so. He’d shrugged and said, ‘It’s a good picture.’

Now I could see that Joe liked his wives tall. She was taller than I, maybe five-eleven, and I wasn’t used to being shorter than other women. I had what some people referred to as great hair, those who happened to like wild, red and unmanageable. But Paige had universally great hair. Long, blonde, straight, silky, shampoo-commercial hair. Computer-enhanced hair. Women comfort themselves when they look at magazines, saying, ‘That photo’s been all touched up. No one really has hair like that, or skin like that, or a body like that.’ Paige had all that, along with Jackie O sunglasses, the single accessory our culture associates with style, mystery and a strong, grieving widow and mother . . . or in her case, mama.

Annie called her Mama.

These thoughts bungee jumped through my mind in the eight seconds it took her to rise gracefully on her heels, holding Annie in her arms, and walk towards me, extending her hand. ‘Hi. I’m Paige Capozzi. Zach and Annie’s mother.’

Mother? Define mother. And her name was still Capozzi. Capozzi? Joe Capozzi. Annie Capozzi. Zach Capozzi. Paige Capozzi. And Ella Beene. One of these things is not like the others; one of these things doesn’t belong.

Zach hid behind me, still holding on to my hand.

‘Hey, Zach. You’ve grown so big.’

I heard Marcella mutter next to me, ‘Yeah. Children grow quite a bit in three years, lady.’

Joe Sr said, ‘What’s she – Oh, for Christ’s sake.’ He reached his arm over Marcella’s shoulders as they turned and walked away.

I thought about telling Paige my name. Hi, I’m Ella, Zach and Annie’s mother. Like we were contestants on What’s My Line? I said nothing. People gathered. Joe’s relatives, excluding his parents, all took their turns saying reserved, polite hellos to her, but you’d think it was a family of Brits, not Italians. David stood next to me and said, ‘Why, nice to finally see you, Paige. You’re looking quite radiant . . . ,’ and then under his breath, he whispered to me, ‘for a funeral.’

Aunt Kat, who always acted like an entire welcoming committee bound up in one tiny woman, did manage to say, ‘Come to the house. We’re all going to the house.’ Everyone turned to me.

David said, ‘How hospitable of you, Aunt Kat, to invite Paige to Ella’s home for her.’

I felt my mouth turn up in a smile; I heard myself say to Paige, ‘Yes, of course, please do.’ By then she’d set down Annie, who stood between us looking back and forth, like a net judge in a tennis match. My heels sank into the grass.

Paige said, ‘That would be lovely. My flight doesn’t leave until tomorrow. Thank you.’

I didn’t want to know anything about Paige – not where her flight was returning her to, not what she did for a living, not if she had more children, and if so, not if she would hang around this time to help raise them. But okay. She was leaving. She would stop by the house for an hour at most to pay her respects to a man she had clearly not respected while he was alive, and then she would drive off, and by tomorrow she would fly far, far away, back to the Land of Mothers Who Left.

Gil and David drove the kids and me home. David turned around to say something, then looked at Annie and Zach leaning into my sides and evidently decided to shut up and face front. I stared at the oval scar on the back of Gil’s domed head, wondering how long it had been hiding under his hair before he’d shaved it all off. Was the scar from a childhood wound, from a bike accident in his teens, or had it happened more recently? A quarrel with a crazy lover, before he’d found David?

Annie sighed and said, ‘She’s pretty!’

Annie was three when Paige left. How much could she possibly remember? I asked her, ‘Do you remember her, Banannie?’

Annie nodded. ‘She still smells good too.’

She remembered her scent. Of course. I’d inhaled every one of Joe’s recently worn T-shirts, grateful now for my tendency to let laundry pile up. I sunk my face into his robe every time I walked by where it hung in the bathroom, dabbed his aftershave on my wrists. Of course Annie remembered.

At the house I kept my distance from Paige. It was easy to tell where she went, because the floor seemed to tilt in her direction, as if we were on a raft and I was made of feathers and she was made of gold. Annie came up and leaned against me, and I smoothed back her hair, ran my fingers through her ponytail. Then she was off, taking Paige by the hand, leading her into the kids’ room. My fiercest ally, Lucy, whispered in my ear, ‘That woman’s got nerve,’ but no one else broached the subject. At funerals, it seems most people leave old grudges at home.

And yet. I certainly didn’t want to chat it up with Joe’s ex-wife on the day of his funeral, or any other day. What did she want? Why was she here? Annie kept dividing her time between the two of us, as if she felt some sort of obligation when she should have been thinking of no one other than her six-year-old self and her daddy. Zach wore his path between Marcella, my mom, and me.

Once I walked around a corner to find Paige and Frank’s wife, Lizzie, embracing, crying. My face went hot, and I whirled back around to the crowd in the kitchen. Even though Frank had been Joe’s best friend since eighth grade, I had been in Frank and Lizzie’s house only a handful of times. She and Paige had been close friends. And so, she’d explained to me the first time I met her, she and I would not be. When I’d reached out to shake her hand, she held mine in both of hers and said, ‘You seem like a nice person. But Paige is my best bud. I hope you understand.’ And then she’d turned and walked away, joining in another conversation. Since then, we’d greeted each other, made a few stabs at small talk about the kids, but never once had a real conversation. Joe and I had never so much as had dinner with Frank and Lizzie, always just Frank. Everyone else in Elbow had welcomed me, but Lizzie’s rejection reared at times, chaffing, a sharp pebble in a perfectly fitting shoe.

I fixed Annie and Zach paper plates of food, but it wasn’t long before they started showing signs of utter fatigue; Zach lay across my lap, sucking his thumb, holding his Bubby, his name for his beloved turquoise bunny that had long lost all its stuffing, and Annie was amped up, running in circles, which she frequently did right before she passed out. ‘Come on, you two. Tell everyone good night and I’ll tuck you in.’

‘No!’ Annie whined. ‘I’m not tired.’

‘Honey, you’re exhausted.’

‘Excuse me? Are you me or am I me?’ She had her hand on her jutted hip, and the other finger pointed to her chest. Paige peeked around the corner.

I took a deep breath. Annie could sometimes act like a six-year-old adolescent. The truth was, we were all exhausted. ‘You are you. And I am me. And me is Mommy. As in Mom.’ And I pointed to my own chest. ‘Me.’ I stood up. ‘And what Mom-me says, you do.’

She laughed. I sighed relief. ‘Good one!’ she said, delighted. ‘You got me on that one.’ I looked over to see Paige turning away. The kids made their good-night rounds, Paige hugging each of them and crouching down, talking to them. God, it was weird to see her there, in our house, chatting with our people, holding our children.

In the old rocker in their room, the kids climbed onto my lap and I read to them and stayed until they fell asleep, which was only about five minutes. I noticed a crate of old books that I’d stuck in the back of the closet, now sitting by the rocker. Had the kids dragged that out, looking for something? Most of them were books they’d outgrown or just got bored with, but maybe they seemed new to them again. Or maybe Annie had shown them to Paige.

I slipped out, quietly closing the door. David handed me a shot of Jack Daniel’s and whispered, ‘She left. She’s outta here.’

I wasn’t much of a Jack Daniel’s drinker, but I raised the shot and gulped it, then grabbed Joe’s down jacket and went outside. The fog had unfurled, chilling the air and sending home everyone but the closest friends and family, who had crowded inside, looking at photo albums and getting drunk. Through the picture window I watched them, a portrait of a family enduring; the warm lamplight surrounded them like soft, old worn-in love.

I pulled on Joe’s jacket and headed for the garden. I wanted the company of tomatoes, of scallions, of kale. I craved lying down between their rows, burying my face in their fragrant, damp dirt. Maybe later I’d go down to the redwood circle and lie there, in the middle of that dark arboreal cathedral, Our Lady of Sequoia sempervirens. Joe had told me that the Pomo Indians believed that on a day in October, the forests could talk, that they would give answers to the people’s wishes. But October was still a long way off.

Lucy came running up behind me. ‘No wandering off alone.’

‘Pray tell, why not?’

‘You need a friend. And a good bottle of wine. Even better, a friend with her own vineyard.’ She held up a bottle of wine without a label; the designer was still working on it.

‘Okay, but let me bum a cigarette.’

She shook her head. ‘Don’t have any.’

‘Liar. You’re PMSing.’ I’d kicked a vicious habit fifteen years before in Advanced Biology at Boston U when they showed us a smoker’s lung. I’d transformed into a typical ex-smoker: a zealot who self-righteously preached about seeing the light of not lighting up. But that night a cigarette sounded like salvation. And Lucy was one of those rare breeds who could smoke a few cigarettes a few times a month when she was stressed, usually right before her period. I knew her cycle because it was the same as mine. Moon sisters. We’d met only when I’d moved to Elbow, but we immediately fell into an easy alignment that went way beyond our cycles. She had long black hair, but she said she should have been the redhead because her name was Lucy. Sometimes she called me Ella Mertz. She and David had become my closest friends. Besides Joe.

We ended up sitting on the bench by the garden, smoking without talking. The cigarette hurt my throat, made me light-headed. She handed me the bottle.

‘What, no glasses? Is this the latest craze in Sonoma wine tasting?’

‘Yeah, but usually we wrap it in a brown paper bag too.’

‘Distinguished.’ I tipped the bottle back and took a swig of pinot noir.

A voice came from behind us: ‘I just wanted to say good-bye.’ I jerked around to see Paige, who reached out her hand to me. I couldn’t extend my own because I was holding the bottle of wine in one hand and a Marlboro Light in the other. Class act if there ever was one.

‘Oh, sorry, here . . .’ I stamped out the cigarette and shoved the bottle back at Lucy. ‘I thought you left.’

‘I realized I hadn’t said a word to you since we got here, so I wanted to thank you for letting me come over. I know this must be a difficult time for you.’

I studied her, saw the origins of Annie’s eyes, Annie’s wilful chin, Zach’s noble forehead. ‘Thanks.’

‘You’ve done a good job with the children,’ she said, her voice cracking the slightest bit, a hairline fracture in the marble goddess. ‘I should be going.’

I stood. She raised her chin. I did not want a hug from her and figured she probably did not want a hug from me. But we had been hugging people all day – it was what you did at times like this – and so we gave each other stiff pats on the back, a stiff not-quite hug. She did smell good, much better than I did. Better than cigarette smoke and booze.

When I finally made it to bed, both kids had already left theirs and climbed into ours – mine – and were asleep. I was glad for their company. About two in the morning, Annie sprang up in bed and cried out, ‘Hi, Daddy!’ I jolted awake, expecting to see him standing over us, telling us it was time to get dressed and head out for a picnic.

Annie smiled in the foggy moonlight, her eyes still closed. I wanted to crawl inside her dream and stay there with her. Callie sighed and laid her head back down over my feet. Zach sucked noisily on his thumb while I tried to let the rhythm lull me back to sleep. Exhaustion had settled into my muscles, bones, and every organ – except my brain, which zigzagged incessantly through moments of my life with Joe. Now I tried to guide it to the few conversations we’d had about Paige, digging up the same information I’d once tossed into the No Need to Dwell pile. Back then, I didn’t want to live in the past, not his or mine. I didn’t ask the questions because I didn’t want to know the answers.

But I had wanted to make sure their ending was final, that there was no chance they could get back together. The last thing I wanted to be was a home wrecker.

At the house that first night I met Joe, the only evidence of Paige that I’d noticed was her bathrobe, and when I returned the next evening after a day of job hunting, the bathrobe was gone. Joe must have emptied the house of everything Paige, because I never found another indication that she existed, except for the one photograph of her pregnant.

‘Four months ago,’ Joe had said in his one offer of explanation soon after we met, ‘while the kids and I were at my mom’s for Sunday brunch, she packed up all her things.’ We had been lying in bed, a candle flame still creating moving shadows on the wall, long after our own shadows had stilled. ‘She took all her clothes except her bathrobe, which she’d practically been living in.’

He said Paige had been depressed. She got to the point that she’d forget to change clothes and take a shower. She went to live with her aunt in a trailer park outside of Las Vegas, so at least he knew someone was taking care of her. It was hard for me to imagine someone choosing a trailer park in the desert, leaving behind all the natural beauty of Elbow, the cosy home, let alone Joe and Annie and Zach. But she wouldn’t see him, wouldn’t talk to him. She’d left him a Dear Joe letter.

‘She said she was sorry but that she wasn’t meant to be a mother. That the kids would be better off without her. She said she loved them but she wasn’t good for them. She told me she knew I could do this, that I was a natural father in all the ways she wasn’t a natural mother, that my family would help me . . . blah, blah, fucking blah.’

‘It’s ironic,’ I told him. I thought about keeping my own failures, well, my own, but I’d already blown every dating rule, so there was no point in stopping then. ‘I’ve wanted to have children, but I haven’t been able to. I was depressed and lethargic, too . . . My ex-husband could tell you similar stories about me wearing the same clothes for three days and forgetting to bathe.’

I told him about the five babies that didn’t make it. We held each other tighter, as if our embrace could serve as a perfectly fitted cast that could help heal all the broken parts of us.

My mom had slept on the couch, had a fire going in the woodstove, and was already making coffee and oatmeal, toast and eggs, when I got up. My mother stood in my kitchen in her robe and moccasins, looking like an older version of me – tall, slim, a bit of a hippie – except her braid was salt-and-pepper. I got my red hair from my dad. She held out her arms to me, her silver bracelets clinking, and I entered her hug. Because her husband – my dad – had died when I was eight, she’d been through this, she knew things, but some of them couldn’t be spoken. I loved my mother, but we’d never had the kind of mother–daughter relationship my friends shared with their moms. I’d never screamed that I hated her; we didn’t go through that necessary separation of selves where I declared my individuality, because, truth be told, the shadow cast by my father’s death always loomed between us, keeping us polite and slightly distant. Still, I loved her. I admired her. And I wished, in a way, that I’d felt passionate and comfortable enough to dump my rage and teenage angst on her. Instead, I’d pecked her on the cheek and closed the door to my room and finished my biology homework.

I poured myself coffee and refilled my mom’s cup. Outside, the fog hadn’t budged since the previous night; the cold grey shroud wrapped itself through the trees, as if trying to comfort them from the very cold it was inflicting upon them. The house, though, literally sparkled. I’d inherited my lack of housekeeping skills from my mother, so she hadn’t had much to do with the cleaning. The night before, Joe’s mother had crouched on her arthritic knees, wiping the hardwood as she crawled out of the front door. She’d washed all the dishes, emptied the compost bucket, and thrown the bags of recyclables into the recycling bin. The only remnants of the funeral were the stuffed refrigerator, the stack of sympathy cards from old friends and new, and the proliferation of calla lilies, irises, lisianthus, and orchids that lined the counters and the old trunk we used as a coffee table.

While my mom and I drank coffee by the fire, I asked her in the most casual voice I could muster, ‘So? What did you think of Paige?’

She shrugged, somewhat carefully. ‘A bit . . . I don’t know . . . Barbie comes to mind, I guess. Or maybe it’s insecurity. She’s awfully stiff. And her ankles are a bit on the thick side, don’t you think? Anyway, she’s nothing like you.’ As only a mother could say.

‘Insecure? She’s so . . . composed.’

My mom made a dismissive wave of her hand, then said, ‘It had to be difficult to show up like that . . . But people need to make themselves feel okay. So I can understand why she came. Lord knows all kinds of people came to your father’s funeral.’

She rarely mentioned my dad. ‘Really? Like who?’

‘Oh, you know. I don’t remember who, exactly. It was a long time ago, Jelly.’

Door closed. I knew better than to press further. ‘But what does Paige want? I’m worried about the kids.’

‘You’ve been their mother for three years. Everyone knows that. Including Paige. And with Joe gone, you’re the one constant parent in their lives.’

‘She could come back.’

She sipped her coffee, set down her cup, which read photographers do it in the darkroom. A present Annie had innocently insisted on getting for Joe. ‘I doubt Paige is going to step up now. After three years of doing nothing. And if she did? Like I said, anyone can see you’re their real mom.’ She reached over and grabbed my hand and gave it a long squeeze. She said, ‘We’ve got to talk business. I know it’s the last thing you feel like doing . . .’

‘I don’t feel like doing anything.’

‘I know. But I can help you with the paperwork. And I’ve only got a few more days.’ She said we needed to check into the life insurance policy, call Social Security, request the death certificate. She sat up straighter and smoothed her robe over her lap. ‘Jelly, I can make the preliminary calls, but they’re all going to want to talk to you . . . okay?’

No. It was not okay. But I nodded anyway.

She patted my knee and stood. ‘It will get your mind off that Paige woman.’

Chapter Five (#ulink_c524f029-1d5f-553e-a873-4833ef6543a2)

Marcella came by to watch the kids while my mom and I drove into Santa Rosa to take care of the paperwork side of death. I stared out of the car window at people going about their business – crossing the street, emerging from buildings, from parked cars, putting change in parking meters, laughing – as my mom drove us back towards Elbow, towards the store. I hadn’t told her that Joe had an old life insurance policy that we were in the middle of updating. As in the beginning of the middle. As in he’d talked to Frank’s dad’s insurance guy, but I hadn’t heard anything else. I thought the old policy was around $50,000, which would buy me a little time to figure out what to do, but not a lot, and this would worry my mom.

Back in San Diego, I’d worked in a lab in what we used to call the ‘cutting foreskin of biotechnology’ , but I hadn’t kept up on it, hadn’t wanted to, really, since I’d discovered almost my first day on the job that I hated working in a lab. When I was a kid I read Harriet the Spy and felt certain that I wanted to be a spy, or at the least, an investigator. I walked around with my dad’s birding binoculars bouncing on my chest, a yellow spiral-bound notepad jammed in my back pocket. I spied on the mailman. I spied on the neighbours. I spied on our houseguests. I wrote down descriptions just like my dad did when we went bird-watching. But after my dad died, I lost my curiosity about people. They were too complex to capture in a few hastily scribbled notes, too unpredictable and perplexing in their behaviours. I turned my attention to the plants and animals he had started teaching me about just before he died, and later, I majored in biology. Somehow I’d taken a wrong turn and ended up staring at cells under a microscope in that biotech lab instead of tromping through field and lake and wood.

Now I had the guide job for Fish and Wildlife lined up, but it was part-time, not enough for the three of us to live on and keep the store running. The store was Grandpa Sergio’s, Joe Sr’s, and Joe’s legacy.

Sergio had started it as a place where the Italian immigrants could find supplies and keep their heritage alive, fulfil their nostalgic longings for their mother country. But during World War II, some of the Italian men, including Sergio, had been sent to internment camps. When Joe had told me, I’d stupidly said, ‘Sergio was Japanese?’

Joe laughed. ‘Ah, that would be no.’

‘I’ve never heard of any Italian internment. How can that be?’

But Joe explained that, yes, some Italians and Germans, too, had been sent away to camps, though in much smaller numbers than the Japanese Americans. And Italians living in coastal towns had to relocate. Many from Bodega came to Elbow. But there was a reason I’d never heard about Italian internment: No one ever talked about it. The Italian Americans didn’t talk about it, and the U.S. government didn’t talk about it.

‘But it happened,’ Joe said. ‘Grandpa never liked to discuss it. Same with Pop. But that’s why Sergio and Rosemary insisted we call them Grandpa and Grandma instead of Nonno and Nonna. There had been a big push during the war not to speak Italian. Another one of the fallouts was that Capozzi’s Market lost its “Everything Italia” motto and became an Americanized hybrid. The mozzarella made room for the Velveeta. I think the store – along with Grandpa Sergio – kind of lost its . . . passion.’ He shrugged. He took a long pause before he added, ‘Trying to be what it thought it was supposed to be. Playing it safe.’ I wondered, the way Joe’s voice trailed off, if he was talking about himself as much as he was Sergio. But I didn’t ask. Part of me didn’t want to know.

My mom turned into the parking lot where Joe and I had first met. The wooden screen door slammed behind us when we walked in; the floors creaked hello. Joe was everywhere. Every detail, no matter how mundane, now held significance. The store – hybrid as it was – had composition, like his photographs. Somehow, and I don’t quite know how he did it, the way he arranged everything – from the oranges and lemons, the onions and leeks, the Brussels sprouts and artichokes and cabbage in the produce section, to the aisles of canned and boxed goods and even the meat and fish behind the glass case – every item complemented another, so that when you opened that ancient screen door, felt the fan whirring up above and smelled the mixture of old wood and fresh vegetables and hot coffee, saw his scrawl on the chalkboard with the day’s specials, you felt as if you were walking into a photograph of a time when everything was whole and good.

But the store that had been Joe was already fading. His cousin Gina had tried, but her careful handwriting on the chalkboard reminded me of a classroom, not the deli. The produce looked tired. I smelled bleach, not soup. Down one of the aisles, I noticed something that couldn’t have just appeared in the past few days: a layer of dust on the soup cans and boxes of pasta.

I hugged Gina, who was as limp as the lettuce, then went upstairs to Joe’s office. I let my hands linger over his desk before I opened the right-side drawer, pushed back the other files, pulled out the one marked Life Insurance. There it was: $50,000. Marcella and Joe Sr had bought him the policy when he and Paige married, years before the kids were born. We had changed it, naming me as the beneficiary, but increasing the amount became a work in progress. I found the forms from Hank Halstrom Insurance that Joe had started to fill out, but that wave came out of nowhere, and the forms were still here, waiting to be finished, waiting to be sent, waiting for business to pick up, so we could afford the higher payment.

There, on the first page only, was the handwriting that should have been on the chalkboard, the boyish quality of it. I traced the letters with my fingertip. Not long before, he’d sat in the same place, hunched over the same forms, just in case . . . someday . . . Had he wondered about his death then? About how? Or when? Or how the three of us would have to find a way to get up the next day without him, and the next?

I pulled a tissue out of my pocket and blotted the tear that had fallen on the form. I was not going to start that again. I held the tissue against my eyes, as if I could push the tears back inside their ducts. In some ways it was harder to be in the store than at home. Had I even set foot in this office before without Joe? He was the last person to sit in this chair, to rest his rough elbows on this desk, to punch our phone number into this phone, to speak into the receiver, to say, ‘Hey, I’m heading home. Got the milk and peanut butter. Anything else?’

My mom was waiting. I took the insurance file and a thick stack of unopened envelopes that had been shoved in the to-do file.

I hadn’t got involved with the bills. Joe had his system in place when I moved in. Besides, I was a mess when it came to paperwork. My mother would tell me this was an opportunity for personal growth. Time to embrace paperwork. Time to stop blubbering and get home to Annie and Zach.

I walked down the stairs, waved, and thanked Gina. She nodded, her eyes still a bit puffy behind her wire-framed glasses. She’d recently returned to Elbow after leaving Our Sisters of Mercy. At age thirty-two, she’d realized she didn’t want to be a nun and was still reeling from that decision. Joe and I had privately called her his ex-sister cousin.

As I held the door open for my mom, I realized not one customer had come into the store while we’d been there, and it was noon. I knew it had been slow, but not that slow.

‘Find it?’ my mom asked as she backed the Jeep out.

I nodded. Within a couple of minutes we were pulling up the gravel drive, Callie running to meet us. A Ford Fiesta sat parked in my spot. My mom and I looked at each other and both lifted our eyebrows. Neither of us felt up for company, but people were being kind.

The kids’ shoes were set out in a neat line by the front door. How efficient of them, I thought, picking up one of Annie’s pink high-tops. They weren’t even muddy. Probably something they’d learned when they stayed at Lizzie’s. I guessed she might be the type who would have a hand-painted sign that said, mahalo for taking off your shoes. I’d been there so few times and so long ago, I couldn’t remember what their shoe policy was; besides, who was I to argue with a little less tracked-in dirt? But there on the other side of the umbrella stand was a pair of Kenneth Cole leather pumps. I’d never seen Marcella wear any heels higher than an inch. I opened the screen door and said in the cheeriest voice I could muster, ‘Banannie, Zachosaurus, I’m ho-ome!’ No one ran to greet me. No one shouted, Hi, Mommy.

I walked in and set the files on the desk and looked through the window to see if I’d missed them playing in the yard. Annie’s giggle spilled from their room. I walked down the hallway and opened the door. There, in our rocker, were Annie and Zach, sitting on Paige’s lap. Zach was brushing a whisk of her silky hair against his cheek. Paige’s arms looped in a fence around both of them; her hands held out an open book, like a gate. The book was by Dr Seuss, one that had been in the crate from the closet. The cover screamed at me: Are You My Mother?

Chapter Six (#ulink_90524a41-2967-57c8-b494-ec753cde9a87)

‘I missed my plane,’ she said, closing the book and holding it face down. ‘Marcella should be back in a minute. She went to check on Auntie Sophia.’

I nodded, kept nodding. My body shook so hard that one of my knees buckled. A crow shrilled, Caw-caw-caw, through the still damp air, staking its claim on a favourite branch or fence post.

Annie grinned at me, but Zach had already slid off Paige’s lap and grabbed my leg. I picked him up, inhaled his fresh, loamy scent, now mixed with the increasingly familiar scent of Paige’s perfume – jasmine, I was pretty sure. And citrus. But it had echoes of Macy’s, not a garden or an orange grove.

My mother, who’d walked in behind me, placed her hand firmly on my back. ‘Hello,’ she said to Paige. ‘Will you be needing a taxi to the airport, then?’

Paige shook her head. ‘I’ve got the rental car.’ She looked at her watch. ‘And it’s just about time to go.’

That, I thought, is an understatement.

I said, ‘It can take a couple hours if you run into traffic . . . Where are you flying to?’ Siberia? Antarctica? The Moon?

‘Las Vegas. I left my card on the coffee table . . .’

Why the hell would I want your card?

‘. . . so the kids can call anytime.’

Why would they want to call you? They don’t even know you. They know the plumber better than they know you and they don’t call him.