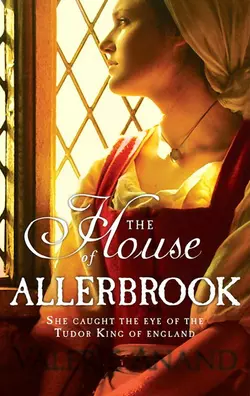

The House Of Allerbrook

Valerie Anand

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фэнтези про драконов

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 308.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: For the first time, Jane beheld King Henry VIII of England.He was broad chested and strong voiced, jewelled and befurred, a powerfully dominant presence… Lady-in-waiting Jane Sweetwater’s resistance to the legendary attractions of Henry VIII may have saved her pretty neck, but her reward is a forced and unhappy marriage to a much older man.Jane’s only consolation is that she still lives upon her beloved Exmoor, the bleak yet beautiful land that cradles Allerbrook House, her family home. Though London may be distant from Exmoor, the religious and political turmoil of the Tudor court are never far away.When Jane is forced to choose, will she remain faithful to the crown of England? Or will family ties bring down the house of Allerbrook?From the glittering danger of the Tudor court to the bleak moors