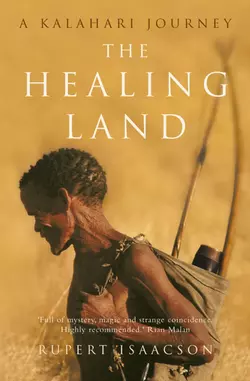

The Healing Land: A Kalahari Journey

Rupert Isaacson

A brilliantly written exploration – part travel writing, part personal quest – of Africa’s oldest and most famous populationThe Bushmen have long been mythologised and are firmly entrenched in the Western mind. But what is it about hunter-gatherers that is so attractive us, and why do we need these myths? Fascinated by this disappearing population, Rupert Isaacson has been venturing into the Kalahari since he was a child and his book is a search for this truth about the Bushmen through Namibia, Botswana and South Africa. Part travel writing, part history of the Bushmen, part personal quest, it will record what he finds there, the landscapes he travels through, the wildlife he hunted and ate, the characters, corruption and confusion of a people who have wrenched themselves out of the Stone Age (it wasn’t until 1948 that it became illegal to kill Bushmen) into a cash economy over the past ten years.

THE HEALING LAND

A KALAHARI JOURNEY

Rupert Isaacson

Copyright (#ulink_de53a308-376f-5a82-846e-5cf655ea939e)

This edition first published in 2002

First published in Great Britain in 2001 by

Fourth Estate

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk

Copyright © Rupert Isaacson 2001

The right of Rupert Isaacson to be identified as the author of this

work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2012 ISBN 9780007393428

Version 2017-08-07

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Dedication (#ulink_58c31f99-bb37-52f9-9f58-49d92cecdc8c)

For the Ancestors

Epigraph (#ulink_059b7838-eb6d-5ed3-a653-8c17f4bc27b7)

Circling, circling …

I have entered the airy, dancing lightness of love.

Rumi

Contents

Cover (#ua699ae14-404d-578a-8685-4c9b63632b2f)

Title Page (#udca538f2-b947-55da-8cea-a7d4f0a6058f)

Copyright (#u43874246-fb8a-5dcd-a7d1-777f2fd37be3)

Dedication (#u2365757c-f38e-5f20-9d29-3e78a8a50091)

Epigraph (#ube739a3a-817a-596e-b18b-a109513f09e3)

Map (#u4535a503-1c89-50ea-9c8c-24ad4c90637e)

Part One: Ancestral Voices (#udff19577-4cc1-5aa1-af6c-09ebba9eb6c9)

1 Stories and Myths (#ud213abe6-bae3-575a-80ef-13312c7685e7)

2 Lessons in Reality (#ub11bd020-6d34-5f09-a4f3-3b804f2d03e5)

3 Under the Big Tree (#ufd4646bf-402b-5763-beea-ccda347cb46d)

Part Two: The Mantis, The Mouse and The Bird (#u3410a0ed-bb5c-56dd-b9b7-2ff23b50adee)

4 Regopstaan’s Prophecy (#u3a1bd958-3c33-52f1-9c46-32e1636e57de)

5 A Human Zoo (#litres_trial_promo)

6 Old Magic, New Beliefs (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Trance Dance at Buitsevango (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Into the Central Kalahari (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: The Good Little Donkeys (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Revelations at the Red House (#litres_trial_promo)

10 The Same Blood (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Dream and Disillusion (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Leopard Man (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Dawid Makes a Request (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Bushman Politics (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Off to See a Wizard (#litres_trial_promo)

16 The River of Spirits (#litres_trial_promo)

17 What Happened After (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Map (#ulink_a2f0774d-1858-5edd-a5b7-5995d4460661)

PART ONE ANCESTRAL VOICES (#ulink_597d2165-f678-5d6c-b268-b058cbda9951)

1 Stories and Myths (#ulink_b877bc75-c052-554d-8ea9-2ddd9b202ab0)

In the beginning, so my mother told me, were the Bushmen – peaceful, golden-skinned hunters whom people also called KhoiSan or San. They had lived in Africa longer than anyone else. Africa was also where we were from; my South African mother and Rhodesian father were always clear on that. Though we lived in London, my sister Hannah and I inhabited a childhood world filled with images and objects from the vast southern sub-continent. Little Bushman hand-axes adorned our walls; skin blankets, called karosses and made from the pelts of rock hyraxes,

(#ulink_dda241aa-94d3-5443-85c7-2cd0b5ea0eec) hung over the sofa; Bushman thumb pianos, made from soft, incense-scented wood, with metal keys that went ‘plink’ when you pressed down and then released them, sat on the bookshelves next to my mother’s endless volumes of Africana. There were paintings by my maternal grandmother Barbara: South African village scenes of round thatched huts where black men robed in blankets stood about like Greek heroes. Next to them hung pictures by my own mother, of black children playing in dusty mission schoolyards, of yellow grass and thorn trees. In my earliest memory, these objects and my mother’s stories forged a strong connection in my mind between our London family and the immense African landscapes the family had left behind.

I remember my mother playing an ancient, cracked recording of a Zulu massed choir and trying to show me how they danced. ‘Like this, Rupert,’ she said, lifting one leg in the air and stamping it on the floor several times in quick succession. ‘They spin as they jump, so it looks as if they’re hanging in the air for a second before they come down, like this, watch.’ She and I would stamp, wheel and jump, a small blonde woman and a smaller blond boy trying to imitate the lithe warriors of her memory.

When I was about five or six years old, my cousin Harold, a tall, bearded, Namibian-born contemporary of my father’s who had settled in London as a doctor, gave me a small grey stone scraper – a sharply whittled tool that sat comfortably in my child’s hand. It had been found in a cave in the Namib Desert. ‘This’, he told me, ‘might have been made thousands of years ago. But it could also be just a few hundred years old, or perhaps even more recent than that; there are Stone Age people living in Africa right now who still use tools like this.’ I closed my hand around the scraper, marvelling at its smooth, cool surface. ‘Is it worth a lot of money?’ I asked. The big man laughed. ‘Perhaps,’ he said, ‘but maybe it’s more valuable even than money.’

He showed me a glossy coffee-table book, illustrated with colour photographs of Bushmen. They were small and slender, naked but for skin loincloths, and carried bows, chasing antelope and giraffes across a flat landscape covered with waist-high grass. They had slanted, Oriental-looking eyes, and whip-thin bodies the colour of ochre. The women, bare-breasted, wore bright, beaded headbands and necklaces of intricate geometric patterns. According to my cousin, they were a people who lived at peace with nature and each other, whose hunting and tracking skills were legendary and who survived in the driest parts of the desert.

I put the scraper among my treasures – a fox’s skull, a dried lizard, the companies of little lead soldiers, a display of pinned butterflies. Occasionally, in quiet moments, I would take it out, hold it and imagine scraping the fat from a newly flayed animal skin.

I remember, too, my mother reciting this hymn, written down in the nineteenth century, recorded from Bushmen on the banks of South Africa’s Orange River. ‘Xkoagu’, my mother read, pronouncing the ‘Xk’ as a soft click:

Xkoagu, hunting star,

Blind with your light the springbok’s eyes

Give me your right arm

and take my arm from me

The arm that does not kill

I am hungry

My mother knew the power of language and made sure that, though we lived in England and knew and loved its knights and castles, green woods and Robin Hoods, we also felt her birthplace moving in us just as she did.

Around this time another cousin came to stay, Frank Taylor, a childhood playmate of my mother’s. He lived, she told us, on the edge of the great Kalahari, where the Bushmen lived. He had brought a small bow and arrow, which I was encouraged to try. I set one of the pointed shafts to the taut sinew of the bowstring and, at a nod from the grown-ups, let fly at the stairs. The arrow stuck, quivering in the wood. With my head full of longbows and Agincourts, I was impressed by its potentially lethal power. But this bow and arrow, said my mother, was not a weapon of war. It was for hunting the great herds of antelope that thronged the Kalahari grasslands.

Kalahari – what a beautiful word. It rolled off the tongue with satisfying ease, seeming to imply distance. A great wilderness of waving grasses, humming with grasshopper song under a hot wind and a sky of vibrant blue.

My father was less reverent about Africa than my mother. Born in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), he had been an asthmatic Jewish intellectual growing up among tough, bellicose Anglo and Afrikaans boys. He had been bullied right through his childhood, and had quit Africa for Europe at the first opportunity. He would imitate, for our amusement, the buttock-swinging swagger of his old school’s rugby First Fifteen as they marched out onto the field, arranging his moustachioed, black-eyebrows-and-spectacles face into a parody of their arrogant insouciance. All his stories tended to the ridiculous. There was the MaShona foreman of the night-soil collectors, who came round each day on a horse and cart to empty the thunder-boxes of the wealthy whites and called himself ‘Boss Boy Shit’; the adolescent house-boy whose balls and penis used to hang, fruit-like, from a hole in his ragged shorts and who, when asked by my father what the fruit was for, demonstrated by upending the bemused house cat and attempting to jam his penis into its impossibly small anus. The cat had twisted and sunk in its claws: deep, causing the house-boy to run off howling.

My father’s tales, like my mother’s myths, contrasted tantalisingly with the overwhelming ordinariness of our London life. My sister and I, avid listeners, tried to learn the Afrikaans rugger songs like ‘Bobbejaan klim die Berg’ (‘The Baboon climbed up the mountain’), which we quickly corrupted into ‘Old baba kindi bear’. The song’s chorus – ‘Vant die Stellenbos se boois kom weer’ (‘the boys of Stellenbosch will come back again’ – a reference to the Boer War) became ‘for the smelly, bossy boys, come here’. Who, we wondered, were these smelly, bossy boys? What was a kindi bear? How strange and mysterious was this land that our parents came from.

At Christmas my father’s father, Robbie, would visit from Rhodesia where he ranched cattle and farmed tobacco – a feudal baron in a still feudal world. He brought us small gifts – leopards and spiral-horned kudus carved from red African hardwoods. My grandfather presented Africa as somewhere real, a place where actual lives were lived. I would listen to him and my parents argue across the dinner table, bringing the continent into sharper focus. The talk, back then, was mostly of the war of independence then raging in Rhodesia; my grandfather told how the Munts

(#ulink_453324a7-d5bc-5e85-b92f-99e3016ef86f) had attacked his farm and shot his farm manager, burning crops, rustling cattle into the night. When he spoke, Africa came across as a hard, violent place and, with his stern voice, lined face and disapproving stare, he seemed to carry something of this with him as he moved about our London house.

An endless succession of white Africans passed through our lives. They talked incessantly of the land of their birth. There were stories about the barren, blasted Karoo, where only dry shrubs grew, stunted by summer drought and bone-cracking winter frost. And the jungly, mosquito-ridden forests of the Zambezi River where lions and buffaloes, hippos and elephants, crocodiles and poisonous snakes lurked around every corner. Up in the high, cold mountains of Lesotho, the landscape resembled Scotland and was inhabited by proud people who wore conical straw hats, robed themselves in bright, patterned blankets and rode horses between their stony, cliff-top villages. I learned of the rolling grasslands around Johannesburg, known as the ‘highveld’, which stretched to a sudden escarpment that fell away to the game-rich thorn-scrub, the ‘lowveld’ or ‘bushveld’. Long before I ever went to southern Africa, its names and regions had been described to me so many times that I could picture them in my mind’s eye, the landscapes flowing one into the other across the great sub-continent, each more beautiful than the last.

I later came to realise that these eulogies to Africa’s natural beauty arose partly from guilt: the speakers came from families whose forebears had, almost without exception, carved out their wealth in blood. Many of these educated descendants of the colonial pioneers were haunted by the feeling that their ancestors should somehow have known better. Yet they also feared the black peoples whose freedom they so longed for, whose oppression by their own kind caused them such shame. They knew that black resentment of white drew little distinction. They were all too familiar with the violent warrior traditions endemic to most black African cultures, and lived in terror of the great uprisings that must one day inevitably come. For them, the myth of a pure, uncomplicated Africa contrasted favourably with the Africa they actually knew. It was a sense of this that they, no doubt unconsciously, imparted to us as wide-eyed London children, and which resonated deeply in my magic-starved mind. Only years later did I realise that, with the exception of cousin Frank, most of these white African visitors knew little or nothing of the bush, let alone the Bushmen. For the most part, they were urbanites much more at home in European cities than out on the dry, primordial veld.

When I was eight and Hannah eleven, our parents took us to Rhodesia to visit my grandfather Robbie. From the moment we stepped off the plane I found the place as seductively, intensely exciting as all the stories had led me to expect. ‘Take off your shoes,’ my mother said, as we pulled up at Robbie’s house, set in a landscaped garden in a white suburb of the capital Salisbury (now Harare). ‘You’re in Africa now and kids go barefoot.’ Hannah and I did as she bid, despite a dubious look at the green, irrigated lawn, which was crawling with insect life. When my grandfather’s manservant, Lucius, opened the front door, a small, cream-coloured scorpion dropped from the lintel. Lucius whipped off his shoe and killed it, then presented me with the corpse as a trophy. I was thrilled. That night the chorus of frogs in the garden was deafening. My father took us out into the darkness with a torch and at the edge of one of my grandfather’s ornamental ponds showed us frogs the size of kittens.

The war for independence was still being fought at that time. Out at Robbie’s farm a high-security fence ran all the way around the homestead, and the white men carried handguns on their hips (things were later to get so bad that my grandfather hired AK-47-wielding guards and an armoured car to patrol his vast territory). We saw his herds of black Brangus cattle, his tobacco fields and drying houses. At night the drums in the farmworkers’ compound thundered till dawn, while my sister and I lay in our beds and tried not to think about the big spiders that sat on the walls above our sleepless heads.

On a bright, hot morning, after a particularly loud night of drumming, two ingangas (witch doctors) performed a ceremony in the compound. Despite having been born in Africa, none of my family could tell us quite what was going on, but there was frightening power in the singing of the assembled black crowd, in the maniacal dancing of the ingangas, whose faces were hidden by fearsome, nightmare masks. It made me shiver.

At a game reserve near the ruins of Great Zimbabwe,

(#ulink_9e0af383-8d25-5ad7-9630-98680e5b61f8) we visited a friend of the family, a zoologist studying crocodiles in the Kyle River. He had caught four big specimens – between twelve and fifteen feet long – and had penned them in a special enclosure built out into the muddy river. Having asked if we’d like to see them, he guided us into the pen, telling us to stay close to the fence and not approach the great, murderous lizards where they lay half in, half out of the shallows.

For some reason I did not listen and, as the man was explaining something about crocodile behaviour to my parents, I walked towards the beasts for a closer look. There was a quick, low movement from the water and suddenly I was being dragged backwards by my shirt collar, loud shouting all around. ‘He almost got you!’ panted the zoologist, who had saved me by a whisker. Forever afterwards, my mother would tell the story of how she almost lost her son to a crocodile.

Sometime towards the end of that month-long trip, we went to look at a cave whose walls were painted with faded animals and men – exquisitely executed in red, cream and ochre-coloured silhouettes. The animal forms were instantly recognisable, perfectly representing the creatures we had just seen in great numbers in the game reserves. Standing there in the cool gloom, I picked out lyre-horned impala, jumping high in front of little stickmen with bows and arrows, kudu with great spiralled horns and striped flanks, giraffes cantering on legs so long they had seemed – when we had seen them in real life – to gallop in slow motion. Paintings like these, my mother told us, could be found in caves all over southern Africa. Some were tens of thousands years old. Others were painted as recently as a hundred years ago. But no one, she said, painted any more.

‘Why not?’ I asked.

‘Because the people were all killed,’ answered my mother. ‘And those not killed fled into the Kalahari Desert.’

She told us how, sometime in the middle of the last century, a party of white farmers in the Drakensberg mountains of South Africa had gone to hunt down the last group of Bushmen living in their area. Having seen all the game on which they had traditionally relied shot out, the Bushmen had resorted to hunting cattle and the farmers had organised a commando, or punitive raid against them. After the inevitable massacre up in the high passes, a body was found with several hollowed-out springbok horns full of pigment strapped to a belt around his waist. ‘He was the last Bushman painter,’ said my mother.

Laurens van der Post, whose writings in the 1950s established him as a Bushman guru, included this poignant story in his Lost World of the Kalahari. In his version it is one of his own forebears who went out on a similar raid, sometime in the late nineteenth century, in the ‘hills of the Great River’. Someone in his own grandfather’s family (van der Post’s words), having taken part in the massacre, discovers the body of the dead artist. Over the years I have encountered this story again and again, from the mouths of liberal-minded whites and in books, each time with a different location and twist. Perhaps all of them are true. Like so much that concerns the Bushmen and the great, wide land that used to be theirs, the story has become myth – intangible, impossible to pin down. Irresistible to a small boy of eight.

Back in the grey, drearily ordinary city of my birth, I found that the bright continent had worked its magic on me. I became more curious about our origins, about the dynastic lines going down the generations, and began to quizz my parents on more detail.

Though from vastly different origins and cultures, both sides of the family had gone at the great continent like terriers; yapping, biting and worrying away at it until they had established themselves and become white Africans. On my father’s side were the Isaacsons and Schapiros, poverty-stricken Lithuanian Jews who had emigrated from the small villages of Pojnewitz and Dochschitz (pronounced Dog-Shits) in the early 1900s. They had gone first to Germany, then to the emerging colony of German Southwest Africa, now Namibia, where my grandfather Robbie had been born in 1908. He grew up poor; his father worked at a low-paying job as a fitter on the railways while his mother kept a boarding house in the small capital Windhoek (though one family rumour has it that she was sometimes a little more than a landlady to her male guests).

The German colony was too rigidly anti-Semitic to allow Jews to make easy fortunes. So, on reaching his twenties, my grandfather crossed the great Kalahari, travelling through British Bechuanaland (now Botswana) to Rhodesia, where, after a brief spell selling shoes, he managed to land a job as a trainee auctioneer in a firm owned by another Litvak Jew – one Herschel (known as Harry) Schapiro. There followed a machiavellian rise to fortune: my grandfather courted and married Freda, daughter of this man Schapiro, became head auctioneer, began slowly buying up farms that came to the company cheap and, eventually, took over the firm.

Harry Schapiro himself had a more romantic story. While still a young man in Lithuania he had abandoned his wife Minnie (a notoriously difficult woman, according to my father) and set off into the world to make his fortune. He took a ship to England, intending to go from there to America, but – owing to his lack of English – got on the wrong boat and ended up in Port Elizabeth, just as the Boer War broke out.

(#ulink_88e40b63-296c-5f03-8145-91f5e7d4ac2c) With characteristic opportunism, he enlisted in the Johannesburg Mounted Infantry believing that once the war was over they would be demobbed in the Transvaal – where the gold mines were. Harry spent three years tramping up and down central South Africa without seeing a shot fired. Then, when the Armistice came, the regiment was demobbed not in the mine fields as promised, but back in Port Elizabeth where Harry had started from.

Undaunted, he set out for the Transvaal anyway, only to end up, not a mining magnate as he had hoped, but a butcher in the mine kitchens, where his wife Minnie managed to track him down, having travelled all the way from Lithuania to do so. Harry stayed with her just long enough to sire Freda (Robbie’s wife and my father’s mother, who died from Alzheimer’s while my sister and I were still small), before running away again, this time to Rhodesia, where he graduated from butcher to cattle trader to wealthy owner of a livestock auctioneering house. Minnie, no less resourceful, tracked him down a second time, whereupon he capitulated, though she of course never forgave him.

My father remembered Minnie – by then an old woman – drinking champagne by the gallon and forcing Harry to buy her a neverending stream of expensive gifts – Persian rugs, Chinese vases and the like – which she would then sell, banking the money. Because, she claimed, she never knew when her husband might take it into his head to disappear again. During these latter years she developed delusions of grandeur and used to tell my father that she had married beneath her, having spent her girlhood in a Lithuanian palace. ‘Rubbish, Minnie,’ Harry would harrumph from his armchair, ‘you were born in a hovel.’

My father’s side was successful financially, my mother’s side less so. But the Loxtons were made of epic stuff. My mother’s father Allen, for example, after spending an idyllic boyhood riding his horse Starlight across the rolling green hills of Natal, became a journalist, then a tank soldier in the 8th Army during the war in North Africa. He escaped his burning tank at Tobruk and jumped onto an abandoned motorbike just as the Afrika Korps came running over the dunes. On his return from the war, Allen resumed his career as a journalist, roving all over southern Africa as a feature writer for the Sunday Times and Johannesburg Star. My mother showed us great fat binders full of his cuttings – stories of travels with crocodile hunters, with witch doctors, with Bushmen; the black and white pictures and Boys’ Own language (at which he excelled) conjuring a world of adventure that stood out in stark contrast to the world I knew in London.

No less intrepid, his wife – my grandmother Barbara – also went to the war, putting my mother (then aged three) and aunt (aged five) into a children’s home and roaming the Western Front as a freelance war artist for the South African papers. As with Allen’s cuttings, my mother would show us Barbara’s paintings, which were kept in a big leather trunk in our sitting room. Barbara had painted everything she saw: London families sleeping in the Underground during the Blitz; the Battle of the Bulge, with the American dead lying in the snow of the Ardennes, cut down like wheat by the German Tiger tanks; the blood-spattered agony of the military hospitals; civilians starving on the streets of the Hague. Shortly after Berlin fell, she and a group of other journalists were allowed into Hitler’s eyrie, high in the Bavarian Alps, literally days after the great dictator and his mistress Eva Braun had committed suicide. Barbara rifled the desk drawers and brought back a few of Hitler’s personal effects – minor things like photographs, an Iron Cross or two, and some official documents – to pass on to the children. My sister and I felt proud that my mother’s parents had taken part in this great story.

But the Loxtons paid for their adventurous spirit by being heavy drinkers, prone to irrational rages, and subsequent wallowing remorse. Allen was no exception, and drove Barbara to leave him a few years after their return from the war. The effect on my mother and her sister Lindsay was far-reaching. Once she left Allen, Barbara (who seems to have been kind, but emotionally cool) never had her children to live with her again. Having been put into boarding schools as near infants while their parents went adventuring, they experienced but a brief couple of years of family life before being shunted off once more, to grow up in institutions until they reached university age.

My petite, blonde, bespectacled mother grew up a true Loxton, becoming involved, while at university, in anti-apartheid campaigns. Her old photograph albums show pictures of the time: my mother (a platinum perm atop a Jane Mansfield bust) and a black male student symbolically burning the government’s separate education Bill; my mother speaking on podiums; brawls between Afrikaans students loyal to the system and my mother’s leftist crowd; pictures of more serious attacks by policemen. One in particular stands out: a march by black domestic maids, protesting for better working conditions, charged with batons and dogs. In the foreground, a woman is on the ground, a police-dog savaging her abdomen, the handler’s truncheon raised high, about to deliver a skull-cracking blow to the woman’s head.

By this time Barbara had remarried, and she and her new husband (a politically active, left-wing lawyer named George Findlay) decided it would be best if my mother left the country before the inevitable arrest that must follow such activities. She was glad to get out and go adventuring in the world as her parents had and took the boat to England along with her sister, Lindsay. In England my mother flirted with the ANC, but became diverted – by art school, by meeting my father, himself an African émigré – and settled down to produce my sister and I while embarking on a career as a sculptor and artist. But when I was eighteen months old, and my sister four, my mother took us back to Africa and presented us to Barbara and Allen (who, though as much of an alcoholic as ever, had moved to Johannesburg and started another family).

A year later, both Allen and Barbara were dead. And in a sad postscript to their failed relationship, though they lived at opposite ends of the country they died within hours of each other. One day while at work in the Sunday Times office, Allen collapsed from emphysema (he had been a heavy smoker), and never regained consciousness. A telegram was sent to Barbara. According to her husband, she went quiet, and retired to have a think and be alone with her memories. When he knocked at the door a short time later to see if she was all right, there was no response. He opened the door and found her lying dead from a stroke.

My mother went almost mad with grief. She had at last begun to know her parents, and now suddenly they had been snatched away. Throughout our childhood, she would be prone to periodic depressions, and the sense of being an exile never left her. Unlike my father, who fitted happily into London (he later told me that even in his Rhodesian childhood he had longed for cities: ‘The first time I went to Johannesburg and smelled the car fumes and saw all that concrete around me, I felt an almost sensual thrill of excitement and pleasure’), my mother missed Africa keenly. She expressed it in her sculpture, her painting, almost all of which featured African people, African scenes.

It was perhaps to make up for the loss of her parents, and of all that she had hoped we children would have learned from them, that she became such a willing story-teller. She told us of the four Loxton brothers – Jesse, Samuel, Jasper and Henry – who in 1830 had come to South Africa from the Somerset village of Loxton and immediately dispersed into the wide spaces of the dry north, the area known as the Great Karoo.

Like all the other early Karoo settlers, the Loxtons lived, at first, by pastoral nomadism learned from the Khoi, a people who looked like Bushmen and spoke a similar clicking language, but who lived by herding rather than hunting. Having shown the whites how to follow the rains and where to find water in this unendingly arid land, the Khoi soon found themselves dispossessed, along with the local Bushman clans. By the time the Loxton brothers arrived, the Khoi had been reduced to working for the whites, and the last remaining Karoo Bushman had retreated to mountain strongholds, from where they watched the white men carve out farms by the land’s few natural springs and kill off the game.

For the whites, it was a slow, monotonous existence, enlivened only by hunting, mostly for wild animals, but sometimes also for Bushmen, who would, as their situation became more and more desperate, occasionally materialise from nowhere to raid livestock. For many Karoo settlers, hunting Bushmen became a well-known, if little talked about, sport. I can only speculate that my family must have done as others did.

Eventually, the Loxton brothers bought land and settled down. Henry, the youngest (my great-great-grandfather) trekked over the Drakensberg mountains into Natal – Zulu Country – where he ended up a wagon-maker, wedded to an Afrikaner woman named Agathe-Celeste (my great-great-grandmother), who had been abandoned as an infant in the court of the Zulu king Mpande by her ivory-hunting father. She had spent her girlhood there, re-entering white society only when she became a young woman and married my great-great-grandfather.

There are many stories about Agathe-Celeste. The best was included in a book of African reminiscences (Thirty Years in Africa), written by a bluff old Africa hand called Major Tudor Trevor, who knew my great-great-grandparents well. It concerned her two pet lions – Saul and Deborah. According to the major, these two lions, which Henry Loxton had given to his wife as cubs, had a game. They would wait at the garden hedge, which ran along the pavement and around the street corner, until someone came walking by. When the walker was halfway along the hedge, one of the cubs would slip through the foliage, drop onto the pavement and silently trail the unwitting pedestrian until he or she turned the corner. There the other cub, who had previously slipped through the hedge on that side, would be waiting. It would let out a kittenish roar in the face of the astonished walker, who would then turn and find the other cub behind, roaring too. While the cubs were still small, and could be run off with a shout, the burghers of the town tolerated their game as a charming, harmless local eccentricity.

Around the time that Saul and Deborah were half-grown (‘as big as mastiffs’, wrote Trevor Tudor), a new predikant, or Minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, arrived in town. One Sunday after church, while sitting on the porch with the Loxtons, the major saw this new priest coming up the road, formally turned out in frock coat, black topper and gloves, with a Bible under his arm. ‘At that moment,’ he wrote, ‘out from behind sprang Deborah. She crouched low. The parson heard the thud of her landing and turned round as if to greet a parishioner … then we heard a kind of drawn out sob, his hat fell off, his Bible dropped, and in a flash he turned and ran off down the street …’

Deborah caught up with him in a few easy bounds and, first with one swipe, then another, ripped off his flying coat tails. The predikant put on a spurt, rounded the corner at a gallop, whereupon out jumped Saul, roaring. With a squeal like the air being squeezed from a bagpipe, the predikant crumpled to the ground. Saul climbed onto his chest and began licking his face, intermittently snarling at Deborah to leave off what he considered his kill. The major, meanwhile, was running to the rescue. Coming up on Saul where he lay, pinning the priest to the road, he fetched the half-grown lion a vicious kick in the ribs. But instead of backing off as expected, Saul turned, slashed at the major’s leg and made ready to spring. It was my great-great-grandmother who saved the day, arriving seconds later with a heavy sjambok (giraffe- or hippo-hide whip), ‘at the first stroke of which’, wrote Trevor Tudor, ‘and a stream of abuse in Dutch, the cubs went flying.’ The major remained, ever after, in awe of my great-great-grandmother, referring to her always as ‘that magnificent woman’.

But Henry Loxton could match his wife’s legendary feats. Fording the Komaati River on his horse one night (the river lies at the southern end of what is now the Kruger National Park), he was attacked by a large crocodile but, so the story goes, managed to beat it off with his stirrup iron. Arriving at the little town on the other side, he stamped angrily into the bar of its one, small hotel, and demanded to know what the devil they meant by allowing such a dangerous beast to infest the ford. For answer the barman told him, apologetically, that nobody in town had a rifle of sufficient calibre to tackle the croc. The only big gun was owned by a German tailor who was short-sighted, could barely shoot, and was holding the weapon as a debt for unpaid services. Hearing this, Henry Loxton rushed over to the tailor’s house and demanded that he accompany him to the river.

Once at the ford, Henry got straight down to business: ‘I’ll go and stand in the middle, and when the croc comes I want you to shoot it.’

‘But I can’t shoot,’ protested the unfortunate tailor. ‘What if I hit you? What if I miss?’

Henry considered a moment, then took the man by the shoulders and frog-marched him into the water. ‘Stay there,’ he said menacingly: ‘If you move before the croc comes I’ll shoot you.’ So the tailor waited, trembling, until sure enough, the croc came gliding silently out from the shore. The gun went off, the croc reared up, then collapsed back into the water with an almighty splash, and the tailor sprinted, howling, for the bank. The great reptile was dead. Thanking his reluctant assistant, Henry Loxton gave him back the rifle and continued on his way. Legend has it that, next morning, the tailor’s hair turned white.

Henry and Agathe-Celeste had four sons, all of whom grew up to fight on opposite sides of the Anglo-Boer War (one of them even mustered his own irregular cavalry unit, known as Loxton’s Horse). And it was into this line that Allen, my mother’s father, was born in 1906.

Before the war however, Jesse, one of Henry and Agathe-Celeste’s elder sons, had gone back to the Karoo and founded a small, dusty town which, predictably, he had named Loxton. He married and had a son, Frederick, who, being a chip off the old block, resolved to mark out a private domain for himself, just as his father had done. Frederick set off first for the Eastern Cape, where he married, had children, and tried to settle. But the lure of the wild, empty north where he had been born proved too strong. Soon enough, he abandoned his young family and rode away to the Orange River country, southernmost border of the Kalahari, then the absolute frontier of civilisation.

But even then, in the 1880s, this part of South Africa (still known today as Bushmanland) was fast being tamed, not by whites but by people of mixed white and Khoi blood – the Griqua, Koranna and Baster

(#ulink_acbcde7e-c8d8-54f1-a3e1-057ea5f56912) – who had trekked away from their white masters some decades earlier. Skilled riders and marksmen, these coloured pioneers had claimed the river’s fertile flood-plain, a corridor of green winding through the vast dryness on either side, making fortresses of the many river islands, from which they raided each other’s camps and enslaved the local Bushmen, occasionally attacking the Dutch and British settlements to the south. By the time Frederick Loxton arrived mission stations had been set up and the old raiding culture was giving way to a more settled farm life. But for a white man with a little money, a good horse and a repeating rifle, there remained a free, frontier possibility to the Orange River country. Ignoring the fact that he already had a family back in the Cape, he met and fell in love with Anna Booysens, the striking daughter of one of the Baster kapteins (leaders). When, some years later, news came of the first wife’s death, Frederick married this woman, and was given a dowry of flood-plain land near the present-day town of Keimoes.

On his death in 1894, Frederick left his farms to his three Baster children and they, when they died, left them to theirs. ‘We have coloured cousins?’ I remembered asking my mother. Indeed we did. But where they were now no one in the family knew. Through the decades that preceded and paved the way for apartheid, the white and the coloured Loxtons had drifted irrevocably apart. Cousins with KhoiSan blood. Almost Bushmen. I pictured them as lean, wild-looking people in a barren landscape of red and brown rock cut through by an immense, muddy river.

As childhood turned to adolescence, it became less comfortable to be caught between cultures, to be part English, part African. The stories, artifacts, white African friends and relatives that constituted my life at home began to clash more and more with the reality of living and going to school in England. I didn’t fit in. Was our family English or African, I would be asked? Neither and both, it seemed.

I was restless in London, and began to long for the open air. We had a great-aunt with a farm in Leicestershire, a horsewoman, who spotted the horse gene in me and taught me to hunt and ride across the Midlands turf on an old thoroughbred that she let me keep there.

Though I made friends with some of the other Pony Club children, I continued to feel like an outsider. Still, it was oddly consoling to think of that great network of ancestors and relatives. Somehow the Kalahari, the dry heart of the sub-continent, seemed central to that inheritance and identity that I was – however unconsciously – trying to find.

So, when I was nineteen, I told my grandfather Robbie over Christmas lunch that I wanted to go to Africa again. The following summer, he sent me a plane ticket.

* (#ulink_7a51ab23-6587-5b75-aa13-f4698116262f) Also known as rock rabbits, they are small creatures similar in appearance to the guinea pig. Curiously, their closest known relative is the elephant.

* (#ulink_50f9785d-63da-59eb-989e-f6323a8269d2) A corruption of the Shona word muntu, meaning ‘people’.

* (#ulink_03fe53ec-6756-532b-a975-f9769bd59aba) A walled city, dating from the thirteenth century, founded by the ancestors of today’s MaShona people.

* (#ulink_6e1d4c3e-af65-59cb-8b87-10d2a41ac8a3) The Second Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) resulted in the British annexation of the whole of South Africa outside the Cape colony. The first war, won by the Boers, was in 1880.

* (#ulink_fa745cfb-79fb-5e33-8f8b-98043747f654) ‘Baster’ means ‘bastard’ literally; a term used for people of mixed race.

2 Lessons in Reality (#ulink_1dedb8c0-e0ed-5893-8bcb-f83d7f00dc77)

It was the African winter: dry, cool, dusty. As the plane touched down in Harare, Zimbabwe, in June 1985, I saw that the grass by the runway was yellow-brown and burnt in places, the trees bare and parched-looking. Walking to the customs building, the early morning air was chilly despite the cloudless blue sky. A faint smell of wood smoke, dust and cow dung was borne in on the bone-dry breeze.

I made my way westward across the grassy Zimbabwe Midlands and into the dry, wooded country of southeastern Botswana, hitchhiking and taking buses and trains. On the third day in the freezing dawn I arrived at Gaborone, Botswana’s dusty, sleepy capital. Cousin Frank Taylor picked me up and drove me out to his place in the red ironstone hills west of town, weaving his beat-up car between teams of donkey-drawn carts made from pick-up trucks sawn in half, driven Ben Hur-style by young BaTswana men. Once out of town, the landscape was barren; red, dry and sandy without a single blade of grass (this was in the height of the terrible droughts that afflicted southern Africa from the 1980s right into the mid ’90s) and the tree branches bare of leaves. I had never seen a landscape so desolate and unforgiving. I sneaked a look at cousin Frank. He matched the landscape: tall, spare, with the capable, practical air of a man used to fixing things himself. Sitting in the passenger seat next to him I felt soft and frivolous and stupid.

I had come to expect that all white Africans lived in big houses surrounded by manicured gardens, where soft-footed black servants produced tea and biscuits punctually at eleven, discreetly rang little bells to call one to lunch, and generally devoted all their energy and ingenuity to surrounding one with understated luxury. Frank Taylor’s house – built with his own hands on a stretch of rocky hillside granted him by the local kgotla

(#ulink_a7579666-a48c-5cff-afb5-d5210d4301b2) – was austere: one long room like a dusty Viking’s hall, little furniture and no water, unless you drove down to a communal tap in the village below.

Frank, his wife Margaret and his three sons were all fervent Christians. That evening, the initial exchanges of family news done, Frank fixed his grey seer’s gaze on me and asked: ‘So, at what stage of your spiritual odyssey are you?’

I did not know how to answer, but hid my discomfort behind a façade of chatty, light-hearted banter. Later, not knowing quite what to do with me, Frank enlisted my help in the new house he was building down on the valley floor. I was not handy with tools, knew nothing about mixing cement, dropping plumb lines, fixing car engines, laying pipes, nor even how to change a flat tyre. I began to realise how unrealistic I had been to dream of just floating into the Kalahari of my childhood stories.

Frank had been in Botswana just over twenty years, having left a prosperous family farm in South Africa to come – missionary-like – and devote himself to improving the lot of Botswana’s rural poor. Foremost among these were the country’s Bushmen, most of whom, I learned, had lately been reduced to pauperdom through a sudden upsurge in cattle ranching. During the 1970s, Frank told me, foreign aid money had come pouring into Botswana, and the cattle-owning elite of the ruling BaTswana tribe had used it to carve roads into previously unreachable areas, and to put up wire fences and sink boreholes. The result, for the Bushmen, was disastrous. The game on which they had traditionally relied was killed if it approached the new boreholes, and prevented by the new fences from following the rains. The animals died along the wire in their hundreds of thousands. With the exception of a few clans still living outside the grasp of the ranchers, most of the Bushmen had found themselves, within a few years, enclosed by wire, their age-old food source gone, reduced to serfs looking after other people’s cattle on land that had once been their own.

In the first few years after his arrival in Botswana, Frank had set up several non-profit-making businesses: textile printing, handicrafts, small-scale poultry farms and the like. But these had been mere preliminaries to his real mission. It seemed to him that for the Remote Area Dwellers (as the Botswana government called the Kalahari peoples, Bushman or otherwise), the real way out of destitution lay not in learning to be Westerners, but in marketing the wild foods and medicines that they had been gathering in the bush since time immemorial. It seems a simple enough idea – agroforestry – but back then it was revolutionary. At that time, most NGOs (non-governmental organisations) were trying to turn indigenous people into farmers or small businessmen. The eco-terms that we now take for granted had yet to be coined. Frank was ahead of his time.

Frank borrowed money and established a small nursery of wild, fruit or medicine-producing shrubs and trees beside his house. He had found that these indigenous plants bore fruit even in drought years, and did not exhaust the dry Botswana soil if planted and harvested year to year, as maize and livestock did. He was convinced that the Kalahari peoples could take these traditional plants beyond mere subsistence, that they could be cultivated for both survival and cash, and that there might even be a market abroad for them. The problem was funding.

Listening to Frank explaining all this convinced me that he was the man to take me into the Kalahari. I tried a tactful approach – perhaps I could accompany him on one of his forays into the heartland? But no, came the answer, he was too busy for the next month or two to take any trips into the interior. However, one night his two elder boys (Michael and Peter, already experienced and bushwise at ten and twelve years old) took me up to sleep out on the wild ridge top. Sitting around the fire – which they could kindle, and I could not – they told me stories about the journeys they had made with their father into that interior. I listened intrigued, intimidated and envious that these boys, not yet in their teens, should have experienced so much of what I longed to experience. At dawn, I got up and went by myself to look out over the vast, wild flat lands that yawned away below – the emptiness, the reds and browns and angry dark burnt umber of the rocks and bare trees. I raised my arms in greeting to that harsh land – the land of my fathers.

I bid the Taylors goodbye and went back eastward into Zimbabwe, where my grandfather had arranged for me to stay on a ranch some hours north of Harare. There I was in heaven: I rode horses, handled guns, shot and killed an antelope and felt a surge of genuine bloodlust as I did so. I swam and fished, drank beer and laughed at jokes about blacks and women. I began to understand how my forebears had reinvented themselves, from Litvak Jew to rich auctioneer, from Somerset peasant to empire builder. Then, one hot morning while I was in the swimming pool, reality returned with a bump. Hearing shouting, I surfaced just in time to see my white rancher host land first one fist, then another, in the face of one of his Shona farmworkers who, it turned out, had been AWOL on a drunken binge and had now shown up for work again, useless and reeking.

Later, the ranch’s black foreman and I were sent to round up a steer for slaughter. We cut a half-grown calf out of the herd and drove it into a corral, where a ring of farmworkers lined the outside of the fence, waiting to see the baas make the kill. The big red-faced man wandered into the corral with a rifle and took aim, pointing the barrel at the flat space between the steer’s eyes. What would happen, I wondered, if the bullet missed and hit one of the farmworkers? But his aim was true. He fired, and a fountain of bright blood erupted from the beast’s head. It did not fall down however; instead it stood, staring through the crimson blood that now pumped from the round hole between its eyes. The rancher shot again, still the steer stood there. He shot a third time. Again the beast did not fall, but kept its feet, swaying, its face a stunned mask of gore. Quickly the foreman reappeared, ducked through the bars of the corral with a huge butcher’s knife in his hand, walked briskly up to the dazed, wounded beast and slit its throat. Blood poured out as if emptied from a bucket, the steer letting out a long death-bellow as the life drained out of the jagged cut. It remained standing until the blood stopped flowing, then crashed onto its side, dead at last.

Realising that I was too squeamish for life on an African farm, I left the guns in their locked cabinet and took long walks with the farm boys, who would show me animals and birds and tell me their names in Shona.

The following year, I travelled to Africa again, and this time went ranging over the great sub-continent, visiting all the places of the family stories, before taking a truck up into East Africa to witness the great wildebeest migration of the Serengeti.

But then I left Africa alone for a while, spending a couple of years adventuring in North America and then trying to establish myself as a freelance journalist in London. The need to identify with the land of my fathers seemed to diminish, become less pressing. A constant presence, but no longer an urgent one.

Then one day, out of the blue, a distant Loxton cousin from Australia wrote to my mother, saying that he had spent ten years researching the family and now wanted to put all the clan back in touch with each other. Among his researches, he had traced the Baster Loxtons, the coloured branch of the family, to a wine farm outside a small town called Keimos, at the southern edge of the Kalahari.

It seemed that they had prospered, and had, against the odds, managed to hold onto their land all through the apartheid years despite several attempts by the white government to dispossess them. Their farm, Loxtonvale, extended along several islands of the great river, where the original Baster kapteins had established their stationary pirate strongholds. Gert and Cynthia Loxton had transformed the islands into vineyards and orchards where they produced Chardonnay and sultana grapes and fruit. They also had a cattle ranch up in the southern fringe of the Kalahari.

My mother got the necessary addresses and flew out that year. When she returned, the link between the two sides of the family had been restored. And between these coloured Loxtons and the Taylors (my mother also visited Frank Taylor on that trip and reported that his Veld Products Research organisation was thriving), it seemed that the door to the Kalahari had finally opened a crack.

In 1992, I returned once more, having landed a contract to write a guidebook to South Africa. During my first week back in the country, I visited the Cultural History Museum in Cape Town, where eerie life-like casts of Bushmen (taken from real people, said the plaque) stood on display behind glass as if living people had been frozen in time. As I travelled I read, learning for the first time the proper history of these, the first people of southern Africa, whom academics called ‘KhoiSan’, but whom others called ‘Hottentots’ or ‘Bushmen’.

Many geneticists and anthropologists, I learned, considered the KhoiSan to be the oldest human culture on earth, possibly ancestors to us all. What was certain was that for thirty thousand years, perhaps longer, they had populated the whole sub-continent, pursuing a lifestyle that included hunting, gathering, painting, dancing, but not, it seemed, war (no warrior folk-tales, weaponry or battle sites exist from this time). Then, sometime around the first century AD, the warriors had arrived – black Africans, whom the academics called ‘Bantu peoples’ – migrating down from west and central Africa with livestock acquired, it is thought, from Arab traders in the Horn and the north of Africa. By the Middle Ages these ancestors of the modern nations of MaShona, Zulu, Ndebele, Xhosa, BaTswana and Sotho had pushed the Bushmen out of most of southern Africa’s lushest areas – what is now Zimbabwe and eastern South Africa. They kept Bushman girls as concubines and adopted some of the distinctive clicks that punctuated the KhoiSan languages. Rainmaking ceremonies and healing practices were also absorbed into the new dominant culture. By the time the first whites settled the Cape in the mid-seventeenth century, the Bushmen had vanished from almost everywhere except for the more rugged mountain ranges and the dry Karoo and Kalahari regions.

Some Bushmen clans, however, took on the culture of the invaders, adopting warrior traditions alongside the herds of cattle and fat-tailed sheep. These peoples – the Khoi or Hottentots – first traded with, then fought, the white settlers, confining the colony to a small settled area around modern-day Cape Town for a generation until successive waves of smallpox in the early eighteenth century so reduced the Khoi that they became absorbed into a general mixed-race underclass known today as ‘coloureds’. Only one group of Khoi survived into modern times – the Nama of northwestern South Africa and southern Namibia.

Having colonised the Cape, the white settlers began pushing north into the Karoo. Extermination and genocide followed, until by the twentieth century Bushmen survived only in the Kalahari. Now even these remote people, as I already knew from Frank, were under threat from the steady encroachment of black cattle ranchers.

As the year drew to a close, I travelled up to the southernmost edge of the Kalahari, where it reaches down into South Africa in a dunescape of red sands tufted with golden grass, and dry riverbeds shaded by tall camel-thorn trees. Even here, I was told, no Bushmen had been seen since the 1960s, maybe earlier. The crisply khakied reception staff at the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park – a narrow tongue of South Africa that makes a wedge between Namibia and Botswana – pointed vaguely northwards into the shimmering, heat-stricken immensity beyond the reception building and told me that I would have to go ‘deep Kalahari’, beyond the park even, if I wanted to see Bushmen.

Once again, it seemed, the gentle hunters of my childhood stories were going to remain just that – fictional characters. Instead, Africa had another kind of experience lined up for me. The year from 1992 to 1993 saw the lead-up to the elections that would change South Africa for ever. Anger that had been seething for generations was starting to erupt. I was researching the Transkei region, down in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province, at this time still one of the ‘tribal homelands’, a region set aside for rural blacks – in this case the Xhosa – to live their traditional lives far away from white eyes. Overcrowding, overgrazing and therefore poverty were the predominant facts of life. Resentment was rife everywhere, but especially so in the Transkei: between the late eighteenth and the late nineteenth centuries, the Xhosa people fought and lost no fewer than nine consecutive wars against the Dutch and the British, forfeiting almost their entire territory in the process. Finally, in despair, all but three clans of the great tribe slaughtered their herds and destroyed their stores of grain, hoping that by this sacrifice their warrior ancestors would rise from the grave and drive the hated white men into the sea. But the ancestors did not come.

This humiliation only whetted the Xhosa’s determination to ultimately win out and beat the white man at his own game – politics. Many black South African leaders, including Nelson Mandela, came from the Transkei. During that pre-election year the region became a focus of anti-white feeling. One night, while in a beach-side rondavel

(#ulink_4607c5ad-ba34-5eea-a14d-2f37d0d2345a) down on the ‘Wild Coast’, Transkei’s two hundred kilometres of beautiful, sparsely inhabited strands, I woke with a start to see a man coming through the window holding a large kitchen knife. As if in a dream, almost without registering that I was doing it, I was out of my sleeping bag and pushing the intruder backwards, so that he fell the few feet to the ground outside with a muffled thud. Still in my dreamlike state, I put my head out of the window to see what was happening. There was a flicker of movement from the left – I jerked back just in time. His friend, who had been pressed against the wall, swung a knobkerrie, missing my head but hitting my shoulder hard. In an instant the mattress was off the bunk and pressed against the window, and the bunk frame was against the door. The bandits thumped and stabbed at both, but there was no way they could get in.

A few days after the attack, I headed back to the Transkei capital, Umtata. Coming out of the store, both hands laden down with shopping bags, I found my way blocked by a large crowd. It was the end of the day and the city’s workers were thronging the main streets, waiting for the minibus taxis that would take them home to their houses on the edge of town. While I was walking through the mass of people, a man approached me, asking the time and, before I could react, had me around the neck while several other hands grabbed me from behind. It was a nasty mugging, the frightened onlookers standing by, pretending nothing was happening, while the fists bloodied my face and mouth and the attackers shouted ‘White shit!’

A week after that, in Pietermaritzburg, Natal – a small, handsome city of red-brick and wrought-iron colonial buildings – I found myself in the midst of a riot. Chris Hani, the head of the South African Communist Party, which had strong links to the ANC, had been shot dead a few days before by a white supremacist. A nationwide series of ‘mourning and protest marches’ was planned and, though I had seen the warnings on television, I forgot and ended up driving downtown on the scheduled day, intent on picking up my poste restante mail. The streets, usually jammed with commuter traffic, were strangely empty. Turning into Longmarket Street, I felt a little glow of satisfaction at being able to park directly outside the ornate, pedimented entrance to the post office. I stopped the car and got out, slamming the door. Then I heard it. ‘HAAAA!’

I looked around and saw, some two hundred yards up the wide street, a wall of armed Zulu youth approaching at a run. Smoke and licks of flame billowed out from the buildings as they came. ‘HAAAA!’, the shout went up again, and in a flash I remembered the news warning. How could I have been so stupid? I had about thirty seconds in which to make a decision. The car, as bad luck would have it, was having battery problems, so I set off down the street at a sprint, but after just a few paces a door opened on my right and a hand beckoned. It was a bakery-cum-takeaway-shop whose staff had for some reason decided to ignore the news warning and open for business. There was no time for explanations, only to duck down with my saviours behind the counter. The first wave of the crowd swept by, roaring. I risked a look over the top of the counter, just in time to see the shop’s large, plate-glass window explode inwards. Shattered glass, stones, bricks and broken wood flew everywhere. Something sharp hit me on the shoulder, tearing my shirt and leaving a light gash on the skin. I ducked down again, then thought of the car with my laptop in the boot. I got up tentatively from behind the counter and walked out into the crowd of young men, all in their late teens and early twenties, who were milling about, as if deciding what to do. This was the second wave; few of them were armed, as the first, most destructive rank of rioters had been. These second-rankers were less angry, more bent on mischief. It showed in their smiles and the alert, slow-walking set of their bodies. A small group of young men with more initiative than the rest were looting a clothing store on the other side of the street, and that drew most of the crowd’s attention. However, standing around my car was a small knot of youths. Walking up to them I had the odd sensation of watching myself from outside my own body. ‘Morning, morning,’ I said, cheerily, stepping between two gangly teenagers dressed in expensive-looking sweatshirts. They did nothing, merely stood by as I unlocked the door, got in and fired up the engine first time. Waving jauntily, I slipped the clutch, rolled slowly forward and – to my amazement, and probably theirs – the youths stepped aside to let me go.

The volume of people, however, forced me to follow the direction of the crowd. After a couple of minutes, I was back among the first wave of rioters. Here, the street was in mayhem. Most of the youths were brandishing spears, ox-hide shields and kerries and shouting and smashing shop windows – some of them were throwing molotovs into the interiors. I was noticed almost immediately. A tall youth, holding a large rock in both hands, was staring around, looking for something to do with it. When he heard the car engine and turned to see a whitey sitting right in front of him in a car, his eyes opened wide and he made ready to smash the rock through the windscreen on top of me. I looked up at him, making pleading gestures with my hands. The car was still. We locked eyes for a couple of seconds, then abruptly he lowered the rock and gestured with his thumb down the street, shouting ‘Go!’

I sped off, a couple of rocks bouncing loudly but harmlessly off the car roof, but the end of the street was blocked by a wall of young men, making a human chain, presumably waiting for the riot police (and news cameras) to arrive. A shower of rocks greeted my approach, though only one connected, hitting the car bonnet and rolling off. I slowed down, searched for someone to make eye contact with, found a gaze in the human chain and held it with my own, taking my hands off the wheel and making the same pleading gestures as before. It worked. After a moment’s hesitation, in which another two rocks hit the car, the man – who was older than the others, perhaps in his mid-thirties – slipped his arm from the man next to him, made a space in the line and gestured for me to go through. I saw him mouth the words, ‘Quickly, quickly’. The ranks behind grudgingly made way, striking the car with hands, weapons and shouting ‘Kill the Boer! One Settler One Bullet!’ But they let me through. Once on the other side I floored it until I was out of the town centre and making for the suburb where I was staying, listening to the noise of police sirens and helicopters heading back towards the trouble. Later that day, I learned that several people had been killed by the mob.

So many violent incidents followed that year of 1993 that they began to blur into one another. By the time my year was up I had not only failed, for the third time now, to get to the Kalahari, I had not even managed to make contact with my coloured Loxton relatives. Instead, I returned home to London exhausted, feeling that I had run out of luck, doubtful if I would ever return to the land of my fathers.

Eighteen months later, however, I was back, this time to write a guidebook covering the three countries just to the north of South Africa: Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia. By then, 1995, the memory of those violent times in South Africa had faded a little, and my determination to find the Bushmen had reasserted itself. After all, the three countries I had to cover encompassed most of the Kalahari.

This time I was not travelling alone, but with my girlfriend, Kristin, a Californian. By a happy accident we managed to borrow a Land-Rover, the vehicle necessary for penetrating Bushman country. There were to be no detours this time. We picked up the vehicle in Windhoek, the Namibian capital, just around the corner from the Ausspanplatz, the town square where, as a boy, my grandfather Robbie had earned pennies by holding the horses of the farmers when they came to town. Two sweaty driving days later, we arrived at the tiny outpost town of Tsumkwe in Eastern Bushmanland, gateway to the ‘deep Kalahari’.

I had been told, during that previous trip to South Africa, that if you drove about fifteen kilometres from Tsumkwe, you would see some big baobabs rising above the thorns to the south. A track would then appear, leading off towards them. And somewhere at the end of that track were villages of the Ju’/Hoansi Bushmen, who still lived almost entirely the traditional way, by hunting and gathering. We drove through Tsumkwe and out to the east, following these instructions. Sure enough, after twenty minutes or so, several great baobabs rose above the bush away to the right; vast, grey, building-sized trees topped with strangely foreshortened branches. The track appeared. We turned down it. The bush crowded in on either side of the vehicle, wild and lushly green from a season of good rain, swallowing us instantaneously.

We made camp under the largest of the great baobabs, an obese monster almost a hundred feet high, got a fire going and put some water on to boil. Looking around at the surrounding bush, which hereabouts was open woodland, we saw the grass standing tall and green in the little glades and clearings. Everything was in leaf, in flower. Fleshy blooms drifted down from the stunted branches of the baobab, making a faint plop as they landed on the sandy ground below. The blossoms had a strong scent, like over-ripe melon. And then there was a crunch of feet on dead leaves. We turned. Two Bushmen had walked into the clearing.

* (#ulink_e6fadff6-3bff-5159-b8a0-a53a65bed579) Village council.

* (#ulink_81776a8e-21cf-54e9-8fc9-eecb4de0b422) Traditional African round, thatched hut.

3 Under the Big Tree (#ulink_78b76841-f8db-5bb3-a571-c251df35a0fc)

In front walked a lean young man, wearing jeans and a torn white T-shirt, and whose sharp, finely drawn features made one think of a little hawk. Behind him came a shorter, grizzle-headed grandfather with a small, patchy goatee, dressed only in a skin loincloth. Above this curved a rounded belly – though not of fat. Rather it was as if the stomach, under its hard abdominal wall, had been stretched and trained to accommodate great feasts when times were good, as they seemed to be now, with the bush green and abundant with wild fruits. Both men had the golden, honey-coloured skin of full-blooded Bushmen. They stood facing us under the vast tree, silent, as if waiting for us to acknowledge their arrival. ‘Hi,’ I said. Kristin smiled.

Smiling shyly, the younger man stepped closer, into conversational range, and said in slow, perfect English: ‘I am Benjamin. And this is /Kaece [he pronounced it ‘Kashay’], the leader of Makuri village. You are welcome here.’

I had assumed that I would have to get by with signs and gesticulation, so it was startling to be addressed in my own language. Kristin and I got up, told the man Benjamin our names and offered him and /Kaece some coffee, which they accepted. Benjamin squatted down by our fire, while the older man took a seat on a buttress-like bit of baobab trunk, which jutted out from the main body of the tree like a small, solid table, and watched with frank, open curiosity, his eyes round like an owl’s.

‘Where did you learn English?’ I asked, trying to open a conversation, and hoping it wouldn’t sound rude, too direct.

‘Mission School,’ answered Benjamin, holding his coffee cup in both hands and sipping gently. ‘In Botswana,’ and he gestured to the east.

‘Perhaps you have some sugar?’ he added. ‘We like our coffee sweet.’ He smiled. Only when four spoonfuls had been deposited into each mug did he give a thumbs-up sign, turn to me again and repeat: ‘So, you are welcome.’

I looked at this young, articulate man with his perfect English and his good, if slightly frayed, clothes. I noticed that he was wearing Reeboks. ‘Are you from Makuri too?’ I said, gesturing back towards where he and the old man had come from.

‘No,’ said Benjamin. ‘I live at Baraka.’

‘Baraka?’

‘Yes. The field headquarters for the Nyae Nyae Farmer’s Co-operative.’ He pronounced the official-sounding words slowly, as if they did not sit easily on his tongue, using the monotone of one who must mentally translate the words before speaking. ‘Maybe twenty kilometres from here … I am a field officer, an interpreter.’

‘The Nyae Nyae what? What’s that?’ I asked, never having heard of it before.

‘An organisation, you know, an NGO, non-government organisation, aid and development.’ His voice was sleepy, hypnotic. ‘But it’s a problem there. Many problems. Sometimes these people say they want us to be farmers. Then another one comes and says no, we should be hunters. Too many foreign people always telling, telling, telling … They don’t ask us what we want.’ Benjamin’s tone became more vehement: ‘We the Ju’/Hoansi’; pronouncing the name ‘jun-kwasi’, with a loud wet click on the ‘k’.

‘The people round here,’ I ventured, ‘are they farmers then? Do they still hunt?’

‘Oh yes, they are hunting. There is a lot of game here – kudus, you know, wildebeests, gemsboks, everything …’ He took a sip of coffee. Dusk was falling and the birds had ceased their song. He was waiting for me to speak again.

‘Do you still have those skills? I mean, do you still hunt?’ I eyed his Western clothes apprehensively.

Benjamin smiled, inclined his head. ‘Yes, even me, I still have the skills.’

‘Tomorrow …’ I said, suddenly emboldened. ‘Would you take us hunting?’

Benjamin smiled again, a smile that seemed to say he knew that this question had been coming. Perhaps I wasn’t the first to ask. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Tomorrow at dawn we will come for you. We will walk far. Do you have water bottles?’

I looked over at Kristin, whose slim, black-eyed face, tanned dark beneath her freckles, was as excited as my own. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘Yes, we’ll bring everything we need …’

Ten minutes later the two men had walked off into the dusk, the low murmur of their voices carried back to us on the breeze.

It was a hot night, full of flying insects. Small beetles, whirring into the firelight, committed suicide in our cooking pot. Occasionally, while eating our rice stew, we would crunch down on a hard-boiled wing-case. We didn’t care, so elated were we, but turned in early so as to be up before dawn, ready for the hunt. Hunting with the Bushmen. It was finally going to happen.

In the dim pre-dawn the bush came alive with the rustlings of small animals and strange chirruping sounds. The earth smelled greenly alive. It was just cool enough to raise a faint gooseflesh on the arms – a luxury when one thought of the heat to come. We made up the fire and brewed coffee, nursing our excitement, and listening to the chatter and whistle of the waking bush.

Imperceptibly, the blue darkness paled, and there came a lull in the birdsong. The pale light in the clearing blushed slowly from blue to rose, from rose to pink, with here and there a wisp of shining, gilded cloud, reflecting the still unrisen sun. Then, with sudden, astonishing speed, the sky became a vast roof of hammered gold and the sun itself came rising above the black boughs of the eastern bush.

But no one appeared in the clearing. We got the fire going again, made more coffee. Still no one came. Half an hour later, buzzing with the strong camp-brew, we could contain ourselves no longer, but picked up our day-packs, water bottles and cameras and went to find the nyore (village), which we knew lay a half-mile or so through the thick scrub.

We found Makuri village still sleeping. As we entered the circle of tiny, beehive huts, only the nyore’s pack of weaselly, starveling dogs were up to greet our arrival. They rushed towards us, barking. But despite the noise, no one appeared from the huts. We stood sheepishly in the centre of the village, throwing small stones at the dogs to keep them off. It was long past dawn now. The first heat was in the sun. Already some animals would be slinking into shady cover for the day. Were we too late? Had the hunters forgotten us and left already?

The rib-thin dogs began to fight among themselves – one had found a bloody section of tortoise-shell and the others wanted it. They chased and fought around the huts, yapping louder and louder until at last a flap in the low doorway of one of the little huts opened, and a wrinkled face appeared. Old man /Kaece crawled out, straightened stiffly, shouted at the animals to shut up and threw a tin mug at the nearest. He stretched luxuriously, raising his hands above his head, sticking out his hard belly and closing his eyes with the bliss of it. He yawned, then looked our way and, as if noticing us for the first time, nodded to us while energetically scratching his balls inside his xai and hawking up a great gob of phlegm. He spat it out, leant forward to examine the colour, and nodded, as if pleased with what he saw. Then, his morning ritual done, he shuffled over to the next-door hut and banged on the side.

There was a muffled noise from within and Benjamin’s head appeared, his sharp, handsome features bleared with sleep and, I realised later when near enough to smell his breath, with liquor. He crawled out, his good, store-bought clothes rumpled from being slept in. He yawned, looked at us vaguely, as if surprised to find us there. Then a pretty young woman with seductive almond eyes, and an ostrich-eggshell necklace draped over her breasts, ducked out of the opening in the beehive hut behind him, saw us, giggled, and darted away out of sight. Benjamin watched her go, stretching his lower back and obviously making an effort to collect his thoughts.

He nodded at us, looking irritated: ‘OK, yes. I’ll be with you now, now.’ He went to a tree at the edge of the huts and hidden by the thick trunk, urinated in a loud, splashing stream before returning and ducking back inside the hut’s low doorway to reappear a few moments later with his hunting kit. A bow of light-coloured wood, a quiver of arrows made from a hollowed-out root, a digging stick and a short spear, all hanging conveniently over his right shoulder in a bag made from a whole steenbok skin. He went over to another hut, banged on it, and roused a smaller, even slighter-built young man, similarly bleary and clad in T-shirt, jeans and running shoes. This, said Benjamin, was his co-hunter Xau; he turned to the smaller man and said something in Ju/’Hoansi, then looked back at us: ‘Let’s go.’

A moment later we were trotting awkwardly behind the two fit, fleet men, out of the village and into the tall grasses. Despite having just been roused from drunken sleep, they moved fast and fluidly, in deceptively small steps, seeming almost to glide above the ground, so smooth was their stride. Benjamin and Xau cast what seemed only the most cursory glances at the ground as they walked. Every few yards we would come upon a narrow track of red or yellow dust criss-crossed with hoof and paw prints. ‘See,’ Benjamin stopped and pointed. ‘That steenbok, we want him.’ Following his gaze I nodded sagely, though I couldn’t distinguish one track from the next. ‘This morning,’ I said hesitatingly, ‘I’m sorry – I didn’t mean to take you away from your wife. I know you’ve been away in Baraka …’

Benjamin looked at me blankly, then away, stifling a grin. ‘That’, he said, ‘was not my wife.’ He turned quickly and walked on.

A moment later he stopped short, crouched and turned his head, motioning for us to get down too. ‘See’, he whispered, pointing ahead. Through a gap in the thicket I saw a small antelope head turn in our direction for a brief second – all flickering ears, limpid, deep brown eyes and little, straight horns – then, reassured that there was no danger, it dipped to graze again. It was a steenbok, a notoriously shy, alert, nervous antelope and we were very close, not twenty yards away.

Xau crept noiselessly up to Benjamin and, using a fluent, silent language of the hands, enquired what he should do. Benjamin replied in the same way, the fingers of one hand making precise gestures against the palm of the other, and Xau crawled off to the left, making a slight noise that caused the antelope to look his way – away from us.

Slowly, so slowly it almost hurt to watch, Benjamin reached back into his shoulder bag for the bow and quiver. Unscrewing the quiver’s cap of stiffened hide he noiselessly shook out an arrow – sticky and dark below its small steel tip with a poison made from mashed beetle larvae mixed with saliva. He fitted the arrow to his bow string and rose to a half-standing position. One swift movement lifted the bow and poised the arrow to eye level. Leaning forward from the hips, Benjamin looked directly down the shaft at the antelope, who still grazed blithe and unaware. Up arced the arrow, soundlessly covering the intervening yards between us and the steenbok to hiss into the grass behind it. The head and neck flew up, making – for a brief second – a frozen, alarmed silhouette. Then it took off, disappearing into the trees in three great bounds. Benjamin shrugged, smiling a little sheepishly, and went to retrieve his arrow.